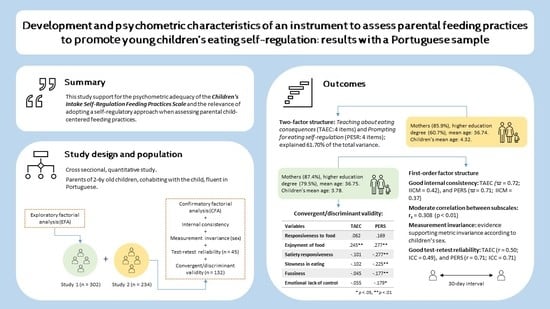

Development and Psychometric Characteristics of an Instrument to Assess Parental Feeding Practices to Promote Young Children’s Eating Self-Regulation: Results with a Portuguese Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Procedures

2.2. Development of the Scale

3. Study 1: Descriptive Analysis of the Items and Factorial Structure of the Scale

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Measures

3.3. Statistical Analysis

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Descriptive Analysis of the Items

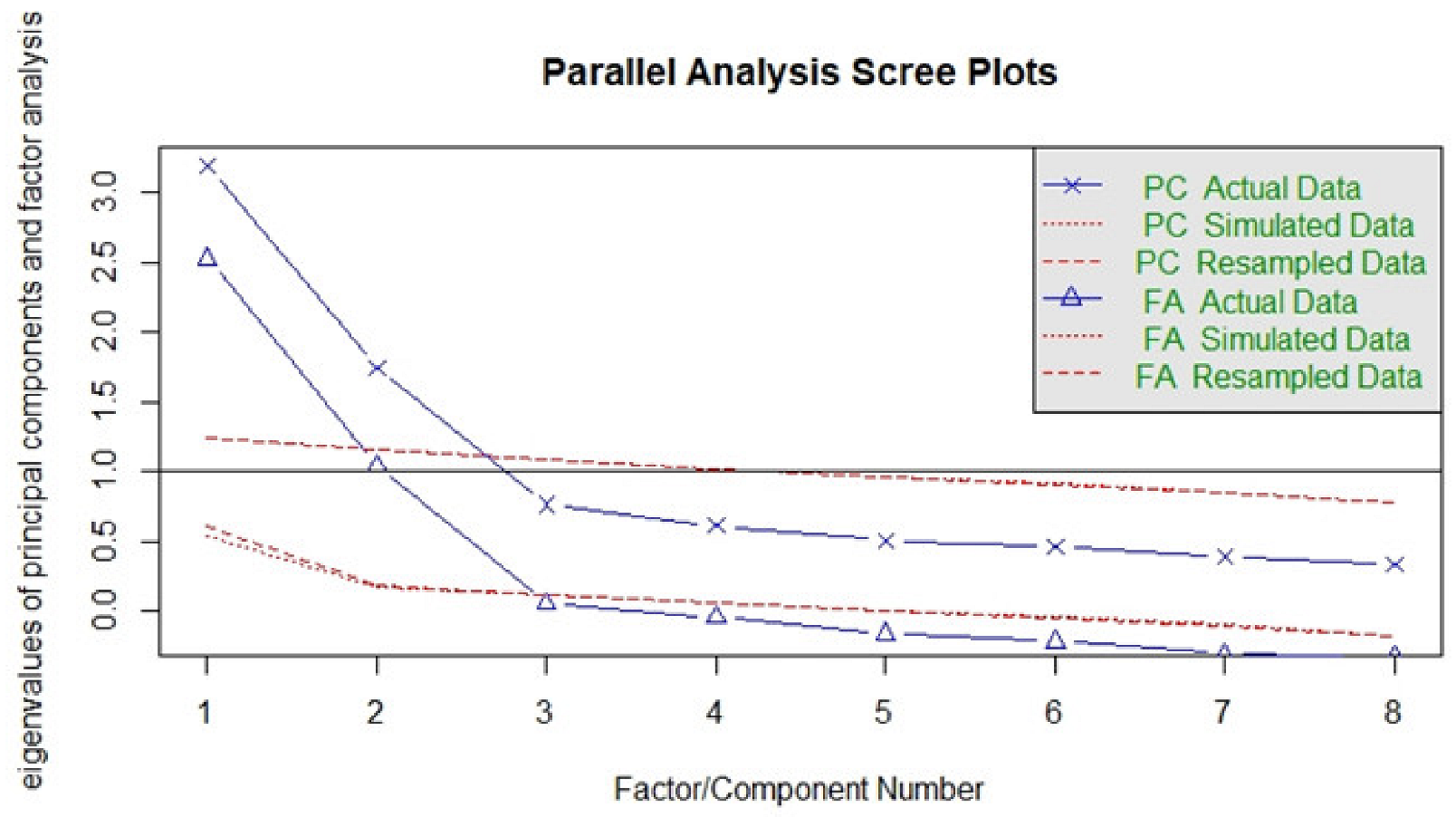

3.4.2. Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA)

4. Study 2: Confirmation of the Factorial Structure, Measurement Invariance, Reliability, and Convergent/Discriminant Validity of the Scale

4.1. Sample Characteristics

4.2. Measures

4.3. Statistical Analysis

4.4. Results

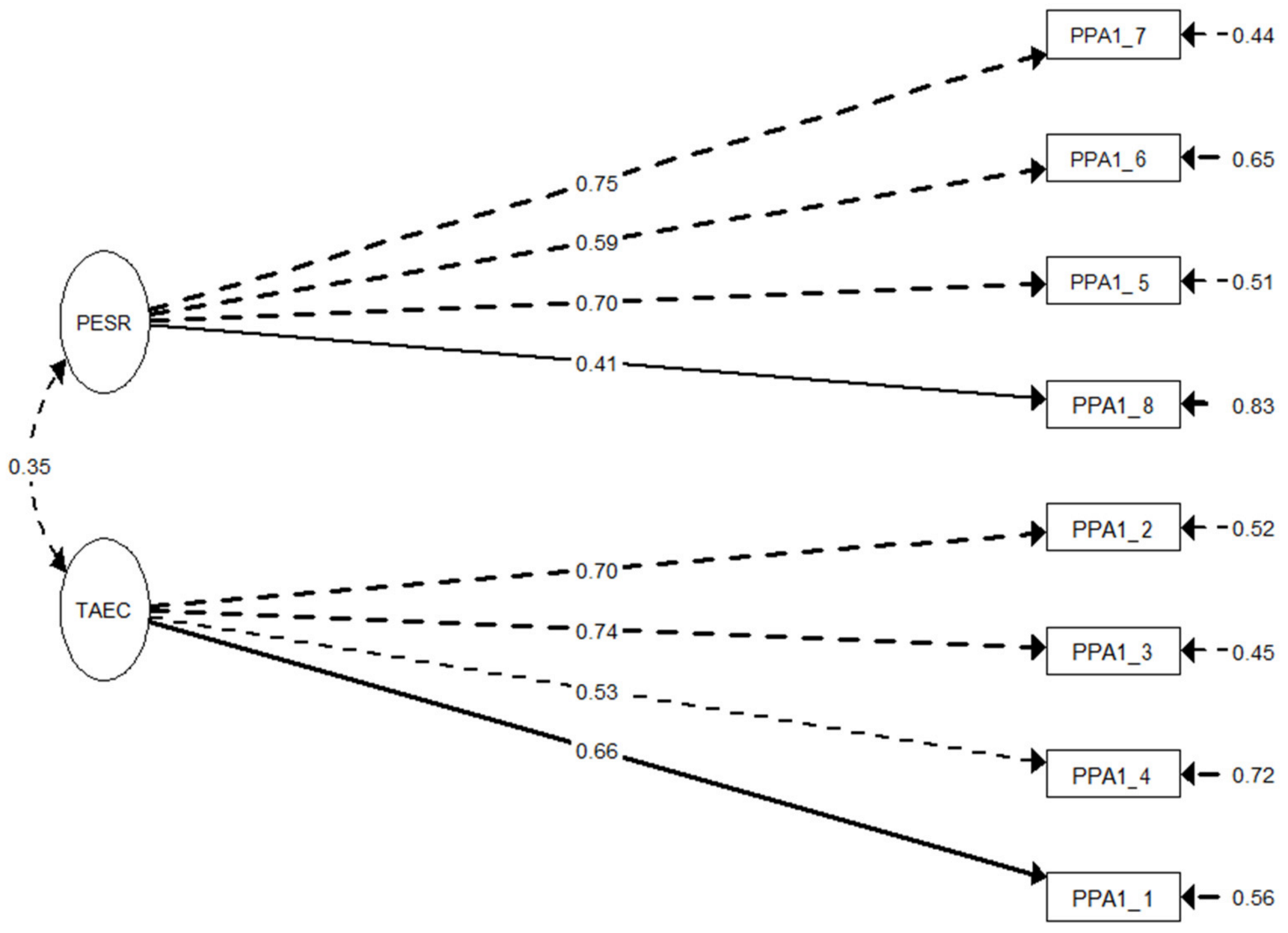

4.4.1. Confirmatory Factorial Analysis and Measurement Invariance

4.4.2. Internal Consistency Reliability and Correlation between Subscales

4.4.3. Test–Retest Reliability

4.4.4. Convergent and Discriminant Analysis

4.4.5. Descriptive Analysis of the Sample

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, S.L. Improving preschoolers’ self-regulation of energy intake. Pediatrics 2000, 106, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellisle, F.; Drewnowski, A.; Anderson, G.H.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.; Martin, C.K. Sweetness, satiation, and satiety. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1149S–1154S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M.K.; Devaney, B.; Reidy, K.; Razafindrakoto, C.; Ziegler, P. Relationship between portion size and energy intake among infants and toddlers: Evidence of self-regulation. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, L.A.; Hughes, S.O.; O’Connor, T.M.; Power, T.G.; Fisher, J.O.; Hazen, N.L. Parental influences on children’s self-regulation of energy intake: Insights from developmental literature on emotion regulation. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 327259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.G.; Russell, A. “Food” and “non-food” self-regulation in childhood: A review and reciprocal analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, L.A.; Susman, E.J. Self-regulation and rapid weight gain in children from age 3 to 12 years. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnell, S.; Wardle, J. Appetite and adiposity in children: Evidence for a behavioral susceptibility theory of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, M.B.; Hallett, A.M.; Ledoux, T.A.; O’Connor, D.P.; Hughes, S.O. Effects of children’s self-regulation of eating on parental feeding practices and child weight. Appetite 2014, 81, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Restricting access to foods and children’s eating. Appetite 1999, 32, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.C.; Blissett, J.M.; Brunstrom, J.M.; Carnell, S.; Faith, M.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Hayman, L.L.; Khalsa, A.S.; Hughes, S.O.; Miller, A.L.; et al. Caregiver influences on eating behaviors in young children: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, N.; Steinberg, L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 113, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.; Williams, K.E.; Mallan, K.M.; Nicholson, J.M.; Daniels, L.A. Bidirectional associations between mothers’ feeding practices and child eating behaviours. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.O. Mothers’ child-feeding practices influence daughters’ eating and weight. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71, 1054–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, B.Y.; Savage, J.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Alternatives to restrictive feeding practices to promote self-regulation in childhood: A developmental perspective. Pediatr. Obes. 2016, 11, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balantekin, K.N.; Anzman-Frasca, S.; Francis, L.A.; Ventura, A.K.; Fisher, J.O.; Johnson, S.L. Positive parenting approaches and their association with child eating and weight: A narrative review from infancy to adolescence. Pediatr. Obes. 2020, 15, e12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Oliveira, A.; Charles, M.A.; Grammatikaki, E.; Jones, L.; Rigal, N.; Lopes, C.; Manios, Y.; Moreira, P.; Emmett, P.; et al. A review of methods to assess parental feeding practices and preschool children’s eating behavior: The need for further development of tools. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1578–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, R.L.; Mobley, A.R. Instruments assessing parental responsive feeding in children ages birth to 5 years: A systematic review. Appetite 2019, 138, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.I.; Pereira, A.I.; Guerreiro, T.; Branco, D.; Roberto, M.S.; Pires, A.; Sousa, J.; Baranowski, T.; Barros, L. SmartFeeding4Kids, an online self-guided parenting intervention to promote positive feeding practices and healthy diet in young children: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2021, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.M.; Binnie, L.M. Children’s concepts of illness: An intervention to improve knowledge. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, H.M.; Baars, R.M.; Chaplin, J.; Zwinderman, K.H. Illness through the eyes of the child: The development of children’s understanding of the causes of illness. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 55, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myant, K.A.; Williams, J.M. Children’s concepts of health and illness: Understanding of contagious illnesses, non-contagious illnesses and injuries. J. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, K.L.; Kling, S.M.; Fuchs, B.; Pearce, A.L.; Reigh, N.A.; Masterson, T.; Hickok, K. A biopsychosocial model of sex differences in children’s eating behaviors. Nutrients 2019, 11, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PORDATA. Alunos Matriculados no Ensino Pré-Escolar: Total e por Idade. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/portugal/alunos+matriculados+no+ensino+pre+escolar+total+e+por+idade-3501 (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Musher-Eizenman, D.; Holub, S. Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire: Validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007, 32, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baranowski, T.; Chen, T.A.; O’Connor, T.; Hughes, S.; Beltran, A.; Frankel, L.; Diep, C.; Baranowski, J.C. Dimensions of vegetable parenting practices among preschoolers. Appetite 2013, 69, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingle, M.; Beltran, A.; O’Connor, T.; Thompson, D.; Baranowski, J.; Baranowski, T. A model of goal directed vegetable parenting practices. Appetite 2012, 58, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Tabak, R.G.; Bryant, M.J.; Ward, D.S. Measuring parent food practices: A systematic review of existing measures and examination of instruments. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Ward, D.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Faith, M.S.; Hughes, S.O.; Kremers, S.P.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R.; O’Connor, T.M.; Patrick, H.; Power, T.G. Fundamental constructs in food parenting practices: A content map to guide future research. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Mâsse, L.C.; Tu, A.W.; Watts, A.W.; Hughes, S.O.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Baranowski, T.; Pham, T.; Berge, J.; Fiese, B.; et al. Food parenting practices for 5 to 12 year old children: A concept map analysis of parenting and nutrition experts input. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, J.L. A rationale and test for the number of components from the matrix of partial correlations. Psychometrika 1965, 30, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Guthrie, C.A.; Sanderson, S.; Rapoport, L. Development of the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2001, 42, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, V.; Sinde, S.; Saxton, J.C. Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: Associations with BMI in Portuguese children. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.O.; Grimm-Thomas, K.; Markey, C.N.; Sawyer, R.; Johnson, S.L. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 2001, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viana, V.; Franco, T.; Morais, C.; Almeida, P.; Silva, D.; Guerra, A. Controlo alimentar materno e estado ponderal: Resultados do Questionário Alimentar para Crianças. [Maternal food control and weight status: Results of the Child Feeding Questionnaire]. Psicol. Saúde Doenças 2012, 13, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.I.; Barros, L.; Roberto, M.S.; Marques, T. Development of the Parent Emotion Regulation Scale (PERS): Factor structure and psychometric qualities. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 3327–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.I.; Barros, L.; Pereira, A.I. Predictors of parental concerns about child weight in parents of healthy-weight and overweight 2-6 year olds. Appetite 2017, 108, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S.R.; Cheek, J.M. The role of factor analysis in the development and evaluation of personality scales. J. Personal. 1986, 54, 106–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, J.L. Amos 18 User’s Guide; Statistical Package for the Social Sciences: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R Package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S. semPlot: Unified visualizations of structural equation models. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2015, 22, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.P. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss, J.L. Reliability of measurement. In The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Power, T.G.; Johnson, S.L.; Beck, A.D.; Martinez, A.D.; Hughes, S.O. The Food Parenting Inventory: Factor structure, reliability, and validity in a low-income, Latina sample. Appetite 2019, 134, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, C.; Santos, A.F.; Fernandes, M.; Santos, A.J.; Bost, K.; Verissimo, M. Caregivers’ perceived emotional and feeding responsiveness toward preschool children: Associations and paths of influence. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, K.; Chabanet, C.; Issanchou, S.; Monnery-Patris, S. Child eating behaviors, parental feeding practices and food shopping motivations during the COVID-19 lockdown in France: (How) did they change? Appetite 2021, 161, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereecken, C.; Rovner, A.; Maes, L. Associations of parenting styles, parental feeding practices and child characteristics with young children’s fruit and vegetable consumption. Appetite 2010, 55, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Totally False (%) | False (%) | Neither True nor False (%) | True (%) | Totally True (%) | Skewness (Std. Error) | Kurtosis (Std. Error) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I tell my child what will happen (e.g., upset stomach, feeling sick) if she eats too many unhealthy foods. | 1.3 | 2.6 | 6.6 | 45.0 | 44.4 | −1.470 (0.140) | 3.063 (0.280) |

| I explain to the child that we can get sick or feel less energy to play when we eat a lot. | 1.7 | 7.9 | 16.9 | 44.7 | 28.8 | −0.822 (0.140) | 0.326 (0.280) |

| I tell my child that eating vegetables and fruits is important, because they make us feel good and with energy. | 0.7 | 1.0 | 7.6 | 50.0 | 40.7 | −1.107 (0.140) | 2.586 (0.280) |

| I explain to the child that some foods, like treats and desserts, should only be eaten occasionally and in small amounts. | 1.0 | 2.0 | 8.9 | 44.4 | 43.7 | −1.127 (0.140) | 2.407 (0.280) |

| I serve small amounts of food to the child and let her have more if she wants. | 0.3 | 2.3 | 14.2 | 61.3 | 21.9 | −0.681 (0.140) | 1.401 (0.280) |

| If the child says she wants seconds, but I think she had enough, I encourage her to stop eating. | 3.0 | 20.5 | 22.2 | 44.7 | 9.6 | −0.413 (0.140) | −0.642 (0.280) |

| When the child says she wants seconds, I ask her if she has an appetite or if she wants more just because she likes that food a lot. | 4.0 | 17.9 | 32.8 | 35.4 | 9.9 | −0.260 (0.140) | −0.466 (0.280) |

| When the child asks for food outside meal times, I ask her to think if she is hungry or just feeling bored. | 7.3 | 33.8 | 37.7 | 17.2 | 4.0 | 0.247 (0.140) | −0.292 (0.280) |

| I try to help the child identify when she is satisfied or still has an appetite. | 4.3 | 12.9 | 33.8 | 39.7 | 9.3 | −0.461 (0.140) | −0.081 (0.280) |

| Items | Factor 1. Teaching about Eating Consequences | Factor 2. Prompting of Eating Self-Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I tell my child what will happen (e.g., upset stomach, feeling sick) if she eats too many unhealthy foods. | 0.809 | |

| 2. I explain to the child that some foods, like treats and desserts, should only be eaten occasionally and in small amounts. | 0.805 | |

| 3. I tell my child eating vegetables and fruits is important, because they make us feel good and with energy. | 0.797 | |

| 4. I explain to the child that we can get sick or feel less energy to play when we eat a lot. | 0.733 | |

| 5. When the child says she wants seconds, I ask her if she has an appetite or if she wants more just because she likes that food a lot. | 0.836 | |

| 6. When the child asks for food outside meal times, I ask her to think if she is hungry or just feeling bored. | 0.752 | |

| 7. I try to help the child identify when she is satisfied or still has an appetite. | 0.730 | |

| 8. If the child says she wants seconds, but I think she had enough, I encourage her to stop eating. | 0.705 | |

| % Explained variance | 31.77 | 29.93 |

| Eigenvalue | 2.54 | 2.40 |

| χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | 90% CI RMSEA | AIC | BIC | df, Δχ2 | Model Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA Models | |||||||||||

| - Model A | 177.705 *** | 20 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.18 | [0.16, 0.21] | 4548.508 | 4603.793 | _ | |

| - Model B | 58.656 *** | 19 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.09 | [0.07, 0.12] | 4431.458 | 4490.198 | 1, 119.05 *** | Model A |

| Gender Multigroup Invariance | |||||||||||

| - Configural Model | 85.718 *** | 38 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.09 | 0.10 | [0.07, 0.13] | 4464.896 | 4637.662 | ||

| - Metric Model | 94.870 *** | 44 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.09 | 0.10 | [0.07, 0.13] | 4462.048 | 4614.083 | 6, 9.1526 | Configural |

| Variables | Teaching about Eating Consequences | Prompting of Eating Self-Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Responsiveness to food (CEBQ) | 0.062 | 0.169 |

| Enjoyment of food (CEBQ) | 0.245 ** | 0.277 ** |

| Satiety responsiveness (CEBQ) | −0.101 | −0.277** |

| Slowness in eating (CEBQ) | −0.102 | −0.225 ** |

| Fussiness (CEBQ) | −0.045 | −0.177 ** |

| Emotional overeating (CEBQ) | −0.091 | 0.054 |

| Emotional undereating (CEBQ) | 0.018 | 0.008 |

| Desire for drinks (CEBQ) | −0.135 | 0.034 |

| Concern of child weight (CFQ-R) | 0.156 | 0.137 |

| Orientation to child’s emotions (PERS) | 0.125 | 0.123 |

| Avoidance of child’s emotions (PERS) | 0.020 | 0.151 |

| Emotional lack of control (PERS) | −0.055 | −0.179 * |

| Vegetables’ and fruits’ intake (CEHQ) | 0.115 | 0.099 |

| Sugar-sweetened foods’ and beverages’ intake (CEHQ) | 0.094 | 0.033 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gomes, A.I.; Roberto, M.S.; Pereira, A.I.; Alves, C.; João, P.; Dias, A.R.; Veríssimo, J.; Barros, L. Development and Psychometric Characteristics of an Instrument to Assess Parental Feeding Practices to Promote Young Children’s Eating Self-Regulation: Results with a Portuguese Sample. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14234953

Gomes AI, Roberto MS, Pereira AI, Alves C, João P, Dias AR, Veríssimo J, Barros L. Development and Psychometric Characteristics of an Instrument to Assess Parental Feeding Practices to Promote Young Children’s Eating Self-Regulation: Results with a Portuguese Sample. Nutrients. 2022; 14(23):4953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14234953

Chicago/Turabian StyleGomes, Ana Isabel, Magda Sofia Roberto, Ana Isabel Pereira, Cátia Alves, Patrícia João, Ana Rita Dias, João Veríssimo, and Luísa Barros. 2022. "Development and Psychometric Characteristics of an Instrument to Assess Parental Feeding Practices to Promote Young Children’s Eating Self-Regulation: Results with a Portuguese Sample" Nutrients 14, no. 23: 4953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14234953

APA StyleGomes, A. I., Roberto, M. S., Pereira, A. I., Alves, C., João, P., Dias, A. R., Veríssimo, J., & Barros, L. (2022). Development and Psychometric Characteristics of an Instrument to Assess Parental Feeding Practices to Promote Young Children’s Eating Self-Regulation: Results with a Portuguese Sample. Nutrients, 14(23), 4953. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14234953