Food Outlet Access and the Healthiness of Food Available ‘On-Demand’ via Meal Delivery Apps in New Zealand

Abstract

1. Introduction

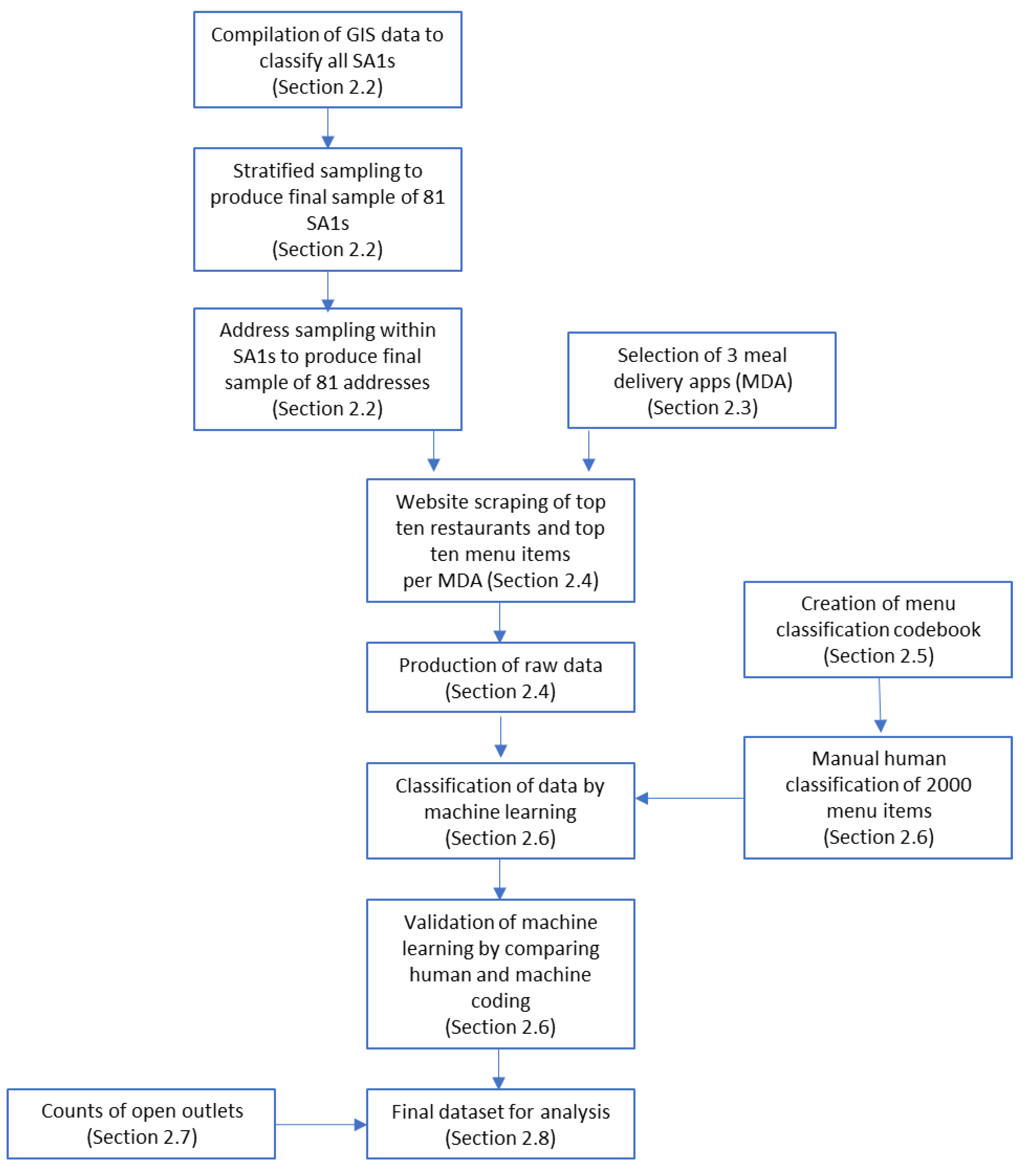

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Study Area

2.2. Address Sampling

- The feature layer 2018 Census Individual (part 1) total New Zealand by Statistical Area 1 [27] containing geography and census ethnicity data. SA1 is the smallest publicly available, aggregated geographical data output from the New Zealand census.

- The table ‘Statistical Area 1 Higher Geographies 2018’ [28], which contains rural and urban classifications for each SA1, including labelling of Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch.

- NZDep, the standard New Zealand Socioeconomic Deprivation Index by SA1 [29].

- Previously compiled locations of ‘dairy and convenience stores’, ‘fast food’ and ‘takeaways’ from the University of Canterbury GeoHealth Laboratory were combined and added as a feature layer of physical outlets providing a preponderance of unhealthy foods [15].

- Locations of New Zealand street addresses from Toitū Te Whenua Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) [30].

- SA1s were filtered to those of ‘Auckland’, ‘Wellington’ or ‘Christchurch’ in the ‘UR2018_V1_00_NAME’ field of the SA1 higher geographies table.

- SA1s were classified into tertiles of physical access to unhealthy foods. This was done by counting the number of unhealthy outlets within an 800 m buffer of the centroid of each SA1.

- SA1s were classified by NZDep tertile within their respective cities according to their associated NZDep score.

- SA1s were classified into those with a higher proportion of Māori (defined as having a proportion of Māori population in the top quintile among SA1s in each city) or not.

2.3. Selection of Meal Delivery Apps (MDAs)

2.4. Data Collection—Website Scraping

- Clear all browsing data and reset the test browser to ensure that any previous searches do not influence future results;

- Search the address of interest;

- Set time for delivery (if supported by the site; searches were performed as close to the time of interest as possible);

- Select each of the first 10 food outlets shown;

- For each food outlet, select the first 10 items;

- Record the item name and description for each item.

2.5. Classification of Food Items

2.6. Machine Learning for Classification of Full Dataset

2.7. Counting Open Outlets

2.8. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lencucha, R.; Thow, A.M. How neoliberalism is shaping the supply of unhealthy commodities and what this means for NCD prevention perspective. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2019, 8, 514–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, D.; Hale, J.; Hutchinson, B.; Kataria, I.; Kontis, V.; Nugent, R. Investing in non-communicable disease risk factor control among adolescents worldwide: A modelling study. BMJ Glob. Health 2019, 4, e001335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.T. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, M.; Marek, L.; Wiki, J.; Campbell, M.; Deng, B.; Sharpe, H.; McCarthy, J.; Kingham, S. Close proximity to alcohol outlets is associated with increased crime and hazardous drinking: Pooled nationally representative data from New Zealand. Health Place 2020, 65, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni Mhurchu, C.; Vandevijvere, S.; Waterlander, W.; Thornton, L.E.; Kelly, B.; Cameron, A.J.; Snowdon, W.; Swinburn, B.; Informas. Monitoring the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages in community and consumer retail food environments globally. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uber Eats. All Cities in New Zealand. 2022. Available online: https://www.ubereats.com/nz/location (accessed on 29 August 2022).

- Statista. Online Food Delivery: New Zealand. 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/eservices/online-food-delivery/new-zealand (accessed on 25 May 2021).

- Stephens, J.; Miller, H.; Militello, L. Food delivery apps and the negative health impacts for Americans. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, H.; Apeldoorn, B.; McKerchar, C.; Curl, A.; Crossin, R. Describing and characterising on-demand delivery of unhealthy commodities in New Zealand. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P. Review of online food delivery platforms and their impacts on sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvarikova, K.; Gajanova, L.; Higgins, M. Adoption of delivery apps during the COVID-19 crisis: Consumer perceived value, behavioral choices, and purchase intentions. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2022, 10, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, G.C.; Whigham, P.A.; Kypri, K.; Langley, J.D. Neighbourhood deprivation and access to alcohol outlets: A national study. Health Place 2009, 15, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, S.; Garton, K.; Gerritsen, S.; Sing, F.; Swinburn, B. How Healthy Are Aotearoa New Zealand’s Food Environments? Assessing the Impact of Recent Food Policies 2018–2021; University of Auckland: Auckland, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.; Blakely, T.; Witten, K.; Bartie, P. Neighborhood deprivation and access to fast-food retailing. A national study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiki, J.; Kingham, S.; Campbell, M. Accessibility to food retailers and socio-economic deprivation in urban New Zealand. N. Z. Geogr. 2019, 75, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, M.P.; Thornton, L.; Zenk, S.N. A cross-sectional comparison of meal delivery options in three international cities. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeble, M.; Burgoine, T.; White, M.; Summerbell, C.; Cummins, S.; Adams, J. Planning and public health professionals’ experiences of using the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets in England: A qualitative study. Health Place 2020, 67, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Needham, C.; Orellana, L.; Allender, S.; Sacks, G.; Blake, M.R.; Strugnell, C. Food retail environments in Greater Melbourne 2008–2016: Longitudinal analysis of intra city variation in density and healthiness of food outlets. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, S.R.; Gibson, A.A.; Roy, R.; Malloy, J.A.; Raeside, R.; Jia, S.S.; Singleton, A.C.; Mandoh, M.; Todd, A.R.; Wang, T.; et al. Junk food on demand: A cross-sectional analysis of the nutritional quality of popular online food delivery outlets in australia and new zealand. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Tatau Kahukura Māori Health Chart Book 2015; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2015.

- Kelly, B.; Bosward, R.; Freeman, B. Australian children’s exposure to, and engagement with, web-based marketing of food and drink brands: Cross-sectional observational study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e28144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Berger, N.; Cornelsen, L.; Eling, J.; Er, V.; Greener, R.; Kalbus, A.; Karapici, A.; Law, C.; Ndlovu, D.; et al. COVID-19: Impact on the urban food retail system and dietary inequalities in the UK. Cities Health 2021, 5 (Suppl. S1), S119–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, M.; Adams, J.; Bishop, T.R.; Burgoine, T. Socioeconomic inequalities in food outlet access through an online food delivery service in England: A cross-sectional descriptive analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2021, 133, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, M.; Adams, J.; Sacks, G.; Vanderlee, L.; White, C.M.; Hammond, D.; Burgoine, T. Use of online food delivery services to order food prepared away-from-home and associated sociodemographic characteristics: A cross-sectional, multi-country analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, L.; Ensaff, H. COVID-19 and the national lockdown: How food choice and dietary habits changed for families in the United Kingdom. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 847547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stats, N.Z. Estimated Resident Population at 30 June 2018 by Territorial Authority and Auckland Local Boards. 2020. Available online: https://datafinder.stats.govt.nz/layer/105009-estimated-resident-population-at-30-june-2018-by-territorial-authority-and-auckland-local-boards/ (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Stats, N.Z. 2018 Census Individual (Part 1) Total New Zealand by Statistical Area 1. 2020. Available online: https://datafinder.stats.govt.nz/layer/104612-2018-census-individual-part-1-total-new-zealand-by-statistical-area-1/ (accessed on 8 September 2022).

- Stats, N.Z. Statistical Area 1 Higher Geographies 2018 (Generalised). 2018. Available online: https://datafinder.stats.govt.nz/layer/92206-statistical-area-1-higher-geographies-2018-generalised/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Atkinson, J. Socioeconomic Deprivation Indexes: NZand NZiDep: Health Inequalities Research Programme (HIRP), University of Otago Wellington. 2019. Available online: https://www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/departments/publichealth/research/hirp/otago020194.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Toitū te Whenua/Land Information New Zealand. NZ Street Address. 2022. Available online: https://data.linz.govt.nz/layer/53353-nz-street-address/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Selenium. WebDriver. 2021. Available online: https://www.selenium.dev/documentation/webdriver/ (accessed on 28 July 2022).

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Norriss, D. Classification Manual. 2022. Available online: https://www.otago.ac.nz/christchurch/research/populationhealth/ (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Ministry of Health. Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults; Ministry of Health: Wellington, New Zealand, 2020.

- IBM Cloud Education. Machine Learning. 2020. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/cloud/learn/machine-learning (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Scikit Learn. 1.17 Neural Network Models Supervised Undated. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/neural_networks_supervised.html#multi-layer-perceptron (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Scikit Learn. 3.1 Cross Validation: Evaluating Estimator Performance Undated. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/cross_validation.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Horta, P.M.; Souza, J.P.M.; Rocha, L.L.; Mendes, L.L. Digital food environment of a Brazilian metropolis: Food availability and marketing strategies used by delivery apps. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 24, 544–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Korai, A.; Jia, S.; Allman-Farinelli, M.; Chan, V.; Roy, R.; Raeside, R.; Phongsavan, P.; Redfern, J.; Gibson, A.; et al. Hunger for home delivery: Cross-sectional analysis of the nutritional quality of complete menus on an online food delivery platform in Australia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Slide to Order: A Food Systems Approach to Meals Delivery Apps: WHO European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, S.; Egli, V.; Roy, R.; Haszard, J.; Backer, C.D.; Teunissen, L.; Cuykx, I.; Decorte, P.; Pabian, S.P.; Van Royen, K.; et al. Seven weeks of home-cooked meals: Changes to New Zealanders’ grocery shopping, cooking and eating during the COVID-19 lockdown. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2021, 51 (Suppl. S1), S4–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breugelmans, E.; Campo, K.; Gijsbrechts, E. Shelf sequence and proximity effects on online grocery choices. Mark. Lett. 2007, 18, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, S.; Sing, F.; Lin, K.; Martino, F.; Backholer, K.; Culpin, A.; Mackay, S. The timing, nature and extent of social media marketing by unhealthy food and drinks brands during the COVID-19 pandemic in New Zealand. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 645349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuber, J.M.; Lakerveld, J.; Kievitsbosch, L.W.; Mackenbach, J.D.; Beulens, J.W. Nudging customers towards healthier food and beverage purchases in a real-life online supermarket: A multi-arm randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2022, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, P.; Braun, M.; Tretter, M.; Dabrock, P. Data sovereignty: A review. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 2053951720982012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. Te Mana Raraunga—The Māori Data Sovereignty Network. 2021. Available online: https://www.maramatanga.co.nz/news-events/news/te-mana-raraunga-m-ori-data-sovereignty-network (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Reviglio, U.; Agosti, C. Thinking outside the black-box: The case for “algorithmic sovereignty” in social media. Soc. Media Soc. 2020, 6, 2056305120915613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, P.M.; Matos, J.D.P.; Mendes, L.L. Food promoted on an online food delivery platform in a Brazilian metropolis during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: A longitudinal analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, K.; Chester, J.; Nixon, L.; Levy, L.; Dorfman, L. Big Data and the transformation of food and beverage marketing: Undermining efforts to reduce obesity? Crit. Public Health 2019, 29, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VicHealth. Dark Marketing Tactics of Harmful Industries Exposed by Young Citizen Scientists Undated. Available online: https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/media-and-resources/citizen-voices-against-harmful-marketing (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Su, D.N.; Nguyen, N.A.N.; Nguyen, L.N.T.; Luu, T.T.; Nguyen-Phuoc, D.Q. Modeling consumers’ trust in mobile food delivery apps: Perspectives of technology acceptance model, mobile service quality and personalization-privacy theory. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2022, 31, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stats, N.Z. 2018 Census Age, Sex, and Ethnicity by Urban Rural 2021. Available online: https://datafinder.stats.govt.nz/layer/106052-2018-census-age-sex-and-ethnicity-by-urban-rural/metadata/?type=dc (accessed on 30 August 2022).

- Bates, S.; Reeve, B.; Trevena, H. A narrative review of online food delivery in Australia: Challenges and opportunities for public health nutrition policy. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloran, A.; Faiz, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Clough, I.; Rippin, H.; Farrand, C.; Weerasinghe, N.; Flore, R.; Springhorn, H.; Breda, J.; et al. The cost of convenience: Potential linkages between noncommunicable diseases and meal delivery apps. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2022, 12, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatlow-Golden, M.; Jewell, J.; Zhiteneva, O.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Breda, J.; Boyland, E. Rising to the challenge: Introducing protocols to monitor food marketing to children from the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, G.; Lean, M.; Anderson, A. Dietary interventions in Finland, Norway and Sweden: Nutrition policies and strategies. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2002, 15, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prättälä, R. Dietary changes in Finland—Success stories and future challenges. Appetite 2003, 41, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items by Score, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unhealthy −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | Healthy 2 | Total | |

| Uber Eats | 2361 (31.7) | 2277 (30.5) | 1114 (14.9) | 1568 (21.0) | 138 (1.9) | 7458 (100.0) |

| Menulog | 2197 (27.2) | 2681 (33.2) | 1680 (20.8) | 1340 (16.6) | 178 (2.2) | 8076 (100.0) |

| delivereasy | 1609 (30.1) | 1632 (30.6) | 646 (12.1) | 1134 (21.2) | 316 (5.9) | 5337 (100.0) |

| Uber Eats | Menulog | Delivereasy | |||||||||||

| Tertile (1 = Least Deprived) | Tertile (1 = Least Deprived) | Tertile (1 = Least Deprived) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Overall | 1 | 2 | 3 | Overall | 1 | 2 | 3 | Overall | ||

| NZDep 2018 | Outlets | 181 (71.5, 258) | 143 (85.5, 187.5) | 163 (107, 202.5) | 156.5 (87.5, 209.5) | 113 (19, 162) | 75 (18, 149.5) | 101 (14, 146) | 95 (16, 158) | 51 (31, 91.5) | 71.5 (53.5, 93.5) | 48 (31.5, 92.5) | 55 (33.5, 93.5) |

| Tertile (1 = Least Dense) | Tertile (1 = Least Dense) | Tertile (1 = Least Dense) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Overall | 1 | 2 | 3 | Overall | 1 | 2 | 3 | Overall | ||

| Physical Density | Outlets | 119 (82.5, 190.5) | 126 (76.5, 187) | 185.5 (153.25, 280) | 156.5 (87.5, 209.5) | 76 (13, 119.5) | 82 (10, 142.5) | 148 (21, 170.5) | 95 (16, 158) | 53 (33, 92) | 48 (32, 89) | 56 (41.5, 95) | 55 (33.5, 93.5) |

| Higher Proportion Māori | Other | Overall | Higher Proportion Māori | Other | Overall | Higher Proportion Māori | Other | Overall | |||||

| Māori Population | Outlets | 119 (85, 182.5) | 170 (102, 270) | 156.5 (87.5, 209.5) | 75 (22, 119) | 105.5 (13.25, 163.75) | 95 (16, 158) | 34 (18, 87) | 55 (44.5, 94) | 55 (33.5, 93.5) | |||

| Uber Eats | Menulog | Delivereasy | |||||||||||

| Tertile (1 = Least Deprived) | Tertile (1 = Least Deprived) | Tertile (1 = Least Deprived) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | ||

| NZDep 2018 | ‘Healthy’ 1 | 543 (21.7) | 607 (24.2) | 556 (22.8) | 1706 (22.9) | 545 (20.2) | 542 (20.2) | 431 (16.0) | 1518 (18.8) | 501 (26.9) | 468 (28.6) | 481 (26.2) | 1450 (27.2) |

| ‘Unhealthy’ 2 | 1965 (78.3) | 1905 (75.8) | 1882 (77.2) | 5752 (77.1) | 2150 (79.8) | 2143 (79.8) | 2265 (84.0) | 6558 (81.2) | 1362 (73.1) | 1170 (71.4) | 1355 (73.8) | 3887 (72.8) | |

| Total Items | 2508 (100) | 2512 (100) | 2438 (100) | 7458 (100) | 2695 (100) | 2685 (100) | 2696 (100) | 8076 (100) | 1863 (100) | 1638 (100) | 1836 (100) | 5337 (100) | |

| Chi2 = 4.5033, p-Value = 0.1052 | Chi2 = 20.9341, p-Value < 0.0001 | Chi2 = 2.5747, p-Value = 0.2760 | |||||||||||

| Tertile (1 = Least Dense) | Tertile (1 = Least Dense) | Tertile (1 = Least Dense) | |||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | ||

| Physical Density | ‘Healthy’ | 623 (24.4) | 539 (22.3) | 544 (21.8) | 1706 (22.9) | 490 (18.2) | 462 (17.2) | 566 (21.0) | 1518 (18.8) | 405 (27.1) | 473 (26.9) | 572 (27.4) | 1450 (27.2) |

| ‘Unhealthy’ | 1928 (75.6) | 1875 (77.7) | 1949 (78.2) | 5752 (77.1) | 2198 (81.8) | 2231 (82.8) | 2129 (79.0) | 6558 (81.2) | 1088 (72.9) | 1283 (73.1) | 1516 (72.6) | 3887 (72.8) | |

| Total Items | 2551 (100) | 2414 (100) | 2493 (100) | 7458 (100) | 2688 (100) | 2693 (100) | 2695 (100) | 8076 (100) | 1493 (100) | 1756 (100) | 2088 (100) | 5337 (100) | |

| Chi2 = 5.4384, p-Value = 0.0659 | Chi2 = 13.905, p-Value = 0.0010 | Chi2 = 0.9497, p-Value = 0.5409 | |||||||||||

| Higher Proportion Māori | Other | Total | Higher Proportion Māori | Other | Total | Higher Proportion Māori | Other | Total | |||||

| Māori Population | ‘Healthy’ | 566 (23.1) | 1140 (22.8) | 1706 (22.9) | 448 (16.6) | 1070 (19.9) | 1518 (18.8) | 459 (27.2) | 991 (27.1) | 1450 (27.2) | |||

| ‘Unhealthy’ | 1888 (76.9) | 3864 (77.2) | 5752 (77.1) | 2250 (83.4) | 4308 (80.1) | 6558 (81.2) | 1227 (72.8) | 2660 (72.9) | 3887 (72.8) | ||||

| Total Items | 2454 (100) | 5004 (100) | 7458 (100) | 2698 (100) | 5378 (100) | 8076 (100) | 1686 (100) | 3651 (100) | 5337 (100) | ||||

| Chi2 = 0.0745, p-value = 0.7848 | Chi2 = 12.7487, p-value = 0.0004 | Chi2 = 0.0038, p-value = 0.9507 | |||||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Norriss, D.; Crossin, R.; Curl, A.; Bidwell, S.; Clark, E.; Pocock, T.; Gage, R.; McKerchar, C. Food Outlet Access and the Healthiness of Food Available ‘On-Demand’ via Meal Delivery Apps in New Zealand. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204228

Norriss D, Crossin R, Curl A, Bidwell S, Clark E, Pocock T, Gage R, McKerchar C. Food Outlet Access and the Healthiness of Food Available ‘On-Demand’ via Meal Delivery Apps in New Zealand. Nutrients. 2022; 14(20):4228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204228

Chicago/Turabian StyleNorriss, Dru, Rose Crossin, Angela Curl, Susan Bidwell, Elinor Clark, Tessa Pocock, Ryan Gage, and Christina McKerchar. 2022. "Food Outlet Access and the Healthiness of Food Available ‘On-Demand’ via Meal Delivery Apps in New Zealand" Nutrients 14, no. 20: 4228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204228

APA StyleNorriss, D., Crossin, R., Curl, A., Bidwell, S., Clark, E., Pocock, T., Gage, R., & McKerchar, C. (2022). Food Outlet Access and the Healthiness of Food Available ‘On-Demand’ via Meal Delivery Apps in New Zealand. Nutrients, 14(20), 4228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204228