Giving Families a Voice for Equitable Healthy Food Access in the Wake of Online Grocery Shopping

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Perceived Causes of Inequity in Access to Healthy Foods and Affected Groups

“The pricing [of healthy food] is wrong. It’s ridiculous that’s causing a lot of obesity, because it’s cheaper for families that go out and get a bucket of chicken or a couple burgers at a fast-food place where they are $1 or less than it is to get something fresh, you know.”[Female, White/Caucasian, SNAP-participant]

3.2. Ways That the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Widened Inequities in Food Access

“With COVID, my stores were out of so much that I didn’t honestly know how we were going to make it, because I had to buy things that were triple the price, just so we would have something to eat versus being hungry. And it wound up being a lot of microwave stuff and a lot of not actual food that didn’t last as long but was triple the price. And sometimes… every time somebody says “Oh, the COVID numbers are rising”, we get the same experience. So the stores are empty, the online stores are empty, and there’s (…) there’s not really any options, especially living in a small area.”[Female, White/Caucasian, non-SNAP participant]

“So you have people who have lost their jobs, or because of COVID, and they’re not receiving help from the government, from the state. Everything’s at a standstill. What do they do? How do they feed themselves? Where do they get the money for food? They can’t work. They have small children who can’t go to daycare because it’s been closed. Can’t go to school because they’ve either completely closed down schools or they’re sending all the kids home to learn online.”[Female, White/Caucasian, non-SNAP participant]

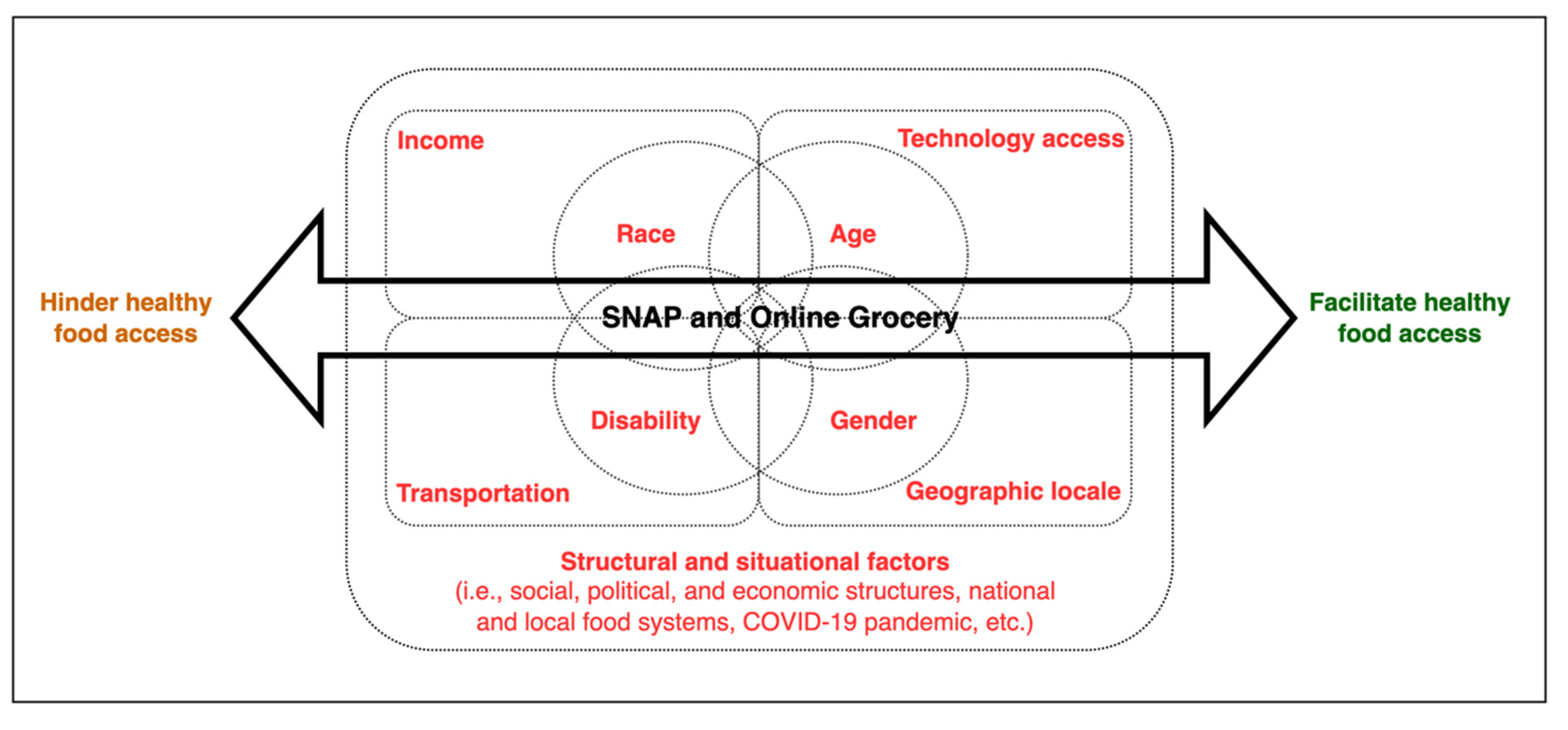

3.3. Healthy Food Access Facilitated or Hindered by SNAP or Online Grocery Services

“[SNAP] makes people be able to afford, afford not only…I mean afford healthy foods, I imagine that’s true. And on top of it, this whole being able to buy things online has got to make, for food deserts, it’s gotta make things better for people in food deserts. If people know they can, I’m assuming most people know now that they can get their food online.”[Female, White/Caucasian, SNAP-participant]

“For me, the bananas—I don’t mind the 99 cents (cost online), but that senior citizen might say, why am I gonna pay 99 cents when I can go to the store and get it for 59 cent in-person to save myself that 40 cents?[Male, Black/African American, SNAP-participant]

“Well me personally (…) they are going to give you food stamps but they don’t ever think how I am going to get to the store, where am I putting this food at if I don’t have a home, what am I doing with this food like I can’t get hot food (…) I am just, I gotta go to the market, every day, and just eat off the card every day, okay.”[Female, Black/African American, SNAP-participant]

“Sometimes, it depends on the store, it depends on the area. Some corner stores in certain areas don’t accept [SNAP] EBT card because they couldn’t get approval, or someone scammed and caused a problem, complained. So they got shut down, so it is one less area for citizens of that community to access food. You need to come up with a way where you’re not discriminated in any way shape or form to where you can eat healthy foods for your family. You know, no, that is not asking for much, that is a basic need, food, you need food to survive.”[Female, White/Caucasian, SNAP-participant]

3.4. Causes and Consequences of Inequities in Healthy Food Access

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Neff, R. Introduction to the US Food System: Public Health, Environment, and Equity; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, A.M.; Painter, M.A. Food insecurity in the United States of America: An examination of race/ethnicity and nativity. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.C.; Reesor, L.M.; Murillo, R. Food insecurity and adult overweight/obesity: Gender and race/ethnic disparities. Appetite 2017, 117, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, C.; Moon, G.; Baird, J. Dietary inequalities: What is the evidence for the effect of the neighbourhood food environment? Health Place 2014, 27, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumanyika, S.K. A framework for increasing equity impact in obesity prevention. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, M.T.; Graves, J.D. Uprooting institutionalized racism as public health practice. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, S.; Toussaint, E.C. Food access in crisis: Food security and COVID-19. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 180, 106859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dorn, A.; Cooney, R.E.; Sabin, M.L. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet 2020, 395, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congress, U. HR 1319–American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- USDA. SNAP Benefits—COVID-19 Pandemic And Beyond. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/benefit-changes-2021 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- USDA. WIC and WIC FMNP—American Rescue Plan Act—Program Modernization. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/american-rescue-plan-act-program-modernization (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- USDA. State Guidance on Coronavirus P-EBT. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/state-guidance-coronavirus-pandemic-ebt-pebt (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- USDA. USDA Farmers to Families Food Box. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/selling-food-to-usda/farmers-to-families-food-box (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Toossi, S.; Jones, J.W.; Hodges, L. The Food and Nutrition Assistance Landscape: Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=101908 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- USDA. Economic Research Service. Online Redemptions of SNAP and P-EBT Benefits Rapidly Expanded Throughout 2020. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/chart-gallery/gallery/chart-detail/?chartId=100944 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Trude, A.C.B.; Lowery, C.M.; Ali, S.H.; Vedovato, G.M. An equity-oriented systematic review of online grocery shopping among low-income populations: Implications for policy and research. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1294–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headrick, G.; Khandpur, N.; Perez, C.; Taillie, L.S.; Bleich, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Moran, A. Content analysis of online grocery retail policies and practices affecting healthy food access. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022, 54, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, E.J.; Silvestri, D.M.; Mande, J.R.; Holland, M.L.; Ross, J.S. Availability of grocery delivery to food deserts in states participating in the online purchase pilot. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1916444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.C.; Beaird, J.; Steeves, E.T.A. WIC participants’ perspectives about online ordering and technology in the WIC program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogus, S.; Guthrie, J.F.; Niculescu, M.; Mancino, L. Online grocery shopping knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors among SNAP participants. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Ng, S.W.; Blitstein, J.L.; Gustafson, A.; Kelley, C.J.; Pandya, S.; Weismiller, H. Perceived advantages and disadvantages of online grocery shopping among special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children (WIC) participants in eastern North Carolina. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Plaza, C.E.; Filomena, S.; Morland, K.B. Disparities in food access: Inner-city residents describe their local food environment. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2008, 2, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes-Maslow, L.; Auvergne, L.; Mark, B.; Ammerman, A.; Weiner, B.J. Low-income individuals’ perceptions about fruit and vegetable access programs: A qualitative study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 317–324.e311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmer, M.; McElrone, M.; Steeves, E.T.A. Feasibility and Acceptability of a “Click & Collect” WIC Online Ordering Pilot. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 2464–2474.E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trude, A.C.; Ali, S.H.; Lowery, C.M.; Vedovato, G.M.; Lloyd-Montgomery, J.; Hager, E.; Black, M.M. A click too far from fresh foods: A mixed methods comparison of online and in-store grocery behaviors among low-income households. Appetite 2022, 175, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Lloyd-Montgomery, J.; Lowery, C.; Vedovato, G.; Trude, A. Equity-Promoting Strategies in Online Grocery Shopping: Recommendations Provided by Households of Low-Income. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2022; under review. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, T. Consumer values, the theory of planned behaviour and online grocery shopping. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornberg, R.; Charmaz, K. Grounded theory and theoretical coding. SAGE Handb. Qual. Data Anal. 2014, 5, 153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, C.O.; Salay, E. A review of food service selection factors important to the consumer. Food Public Health 2013, 3, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAXQDA. All-In-One Qualitative & Mixed Methods Data Analysis Tool. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Pelto, P.J.; Pelto, G.H. Anthropological Research: The Structure of Inquiry; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, A.D.M.; van Lenthe, F.; Kamphuis, C.B.M.; Terragni, L.; Roos, G.; Poelman, M.P.; Nicolaou, M.; Waterlander, W.; Djojosoeparto, S.K.; Scheidmeir, M.; et al. Dynamics of the complex food environment underlying dietary intake in low-income groups: A systems map of associations extracted from a systematic umbrella literature review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brantley, E.; Pillai, D.; Ku, L. Association of Work Requirements with Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation by Race/Ethnicity and Disability Status, 2013–2017. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e205824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, E.F.; Delmelle, E.; Major, E.; Solomon, C.A. Accessibility landscapes of supplemental nutrition assistance program—Authorized stores. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes-Maslow, L.; Hardison-Moody, A.; Patton-Lopez, M.; Prewitt, T.E.; Byker Shanks, C.; Andress, L.; Osborne, I.; Jilcott Pitts, S. Examining rural food-insecure families’ perceptions of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program: A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnack, L.; Valluri, S.; French, S.A. Importance of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in Rural America. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1641–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatz, L.Y.; Moran, A.J.; Franckle, R.L.; Block, J.P.; Hou, T.; Blue, D.; Greene, J.C.; Gortmaker, S.; Bleich, S.N.; Polacsek, M. Comparing shopper characteristics by online grocery ordering use among households in low-income communities in Maine. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 5127–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consavage Stanley, K.; Harrigan, P.B.; Serrano, E.L.; Kraak, V.I. Applying a multi-dimensional digital food and nutrition literacy model to inform research and policies to enable adults in the US Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program to make healthy purchases in the online food retail ecosystem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vedovato, G.M.; Ali, S.H.; Lowery, C.M.; Trude, A.C.B. Giving Families a Voice for Equitable Healthy Food Access in the Wake of Online Grocery Shopping. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204377

Vedovato GM, Ali SH, Lowery CM, Trude ACB. Giving Families a Voice for Equitable Healthy Food Access in the Wake of Online Grocery Shopping. Nutrients. 2022; 14(20):4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204377

Chicago/Turabian StyleVedovato, Gabriela M., Shahmir H. Ali, Caitlin M. Lowery, and Angela C. B. Trude. 2022. "Giving Families a Voice for Equitable Healthy Food Access in the Wake of Online Grocery Shopping" Nutrients 14, no. 20: 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204377

APA StyleVedovato, G. M., Ali, S. H., Lowery, C. M., & Trude, A. C. B. (2022). Giving Families a Voice for Equitable Healthy Food Access in the Wake of Online Grocery Shopping. Nutrients, 14(20), 4377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14204377