When Eating Becomes Torturous: Understanding Nutrition-Related Cancer Treatment Side Effects among Individuals with Cancer and Their Caregivers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Quantitative Data Collection and Analysis

2.4. Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

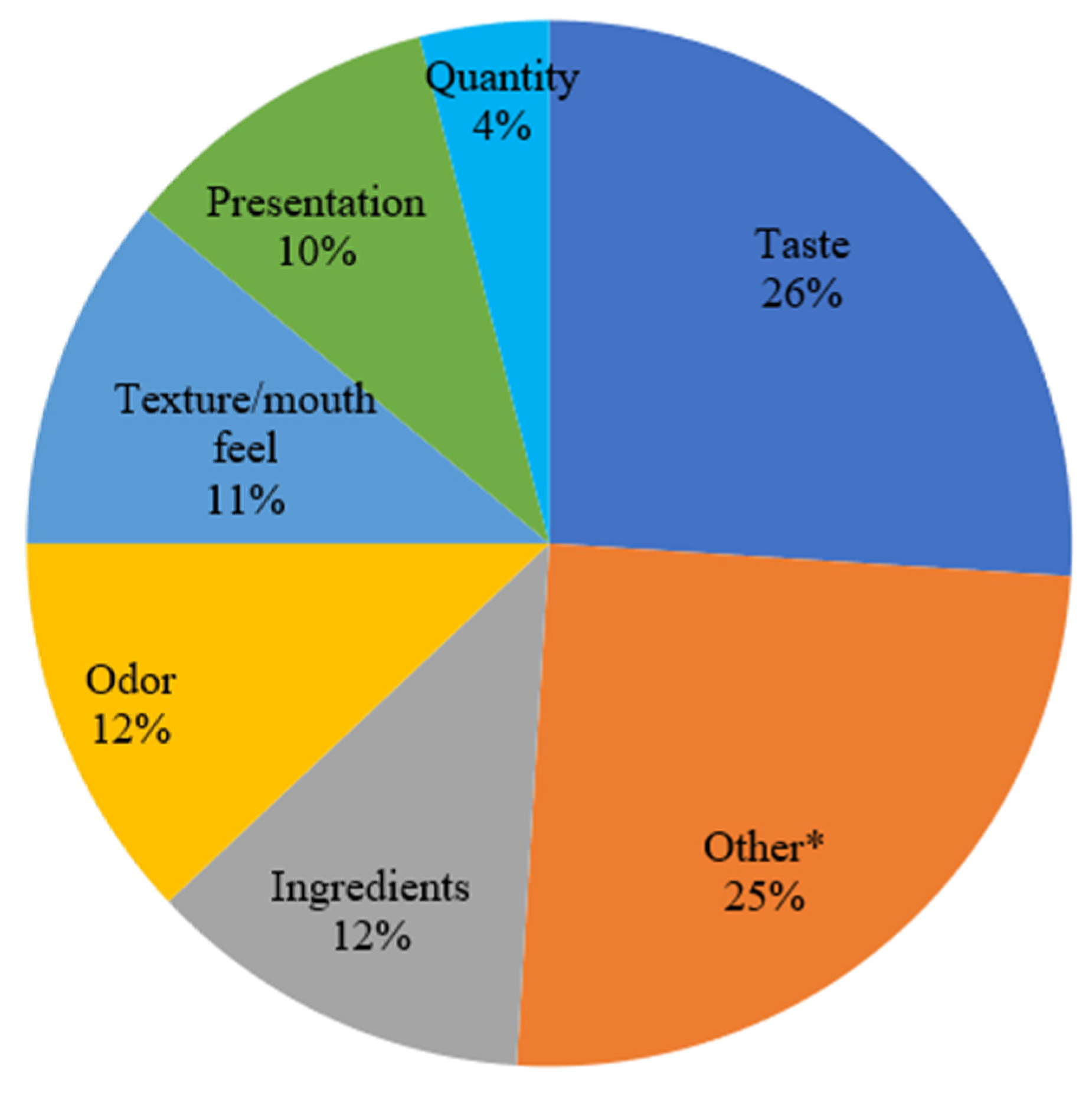

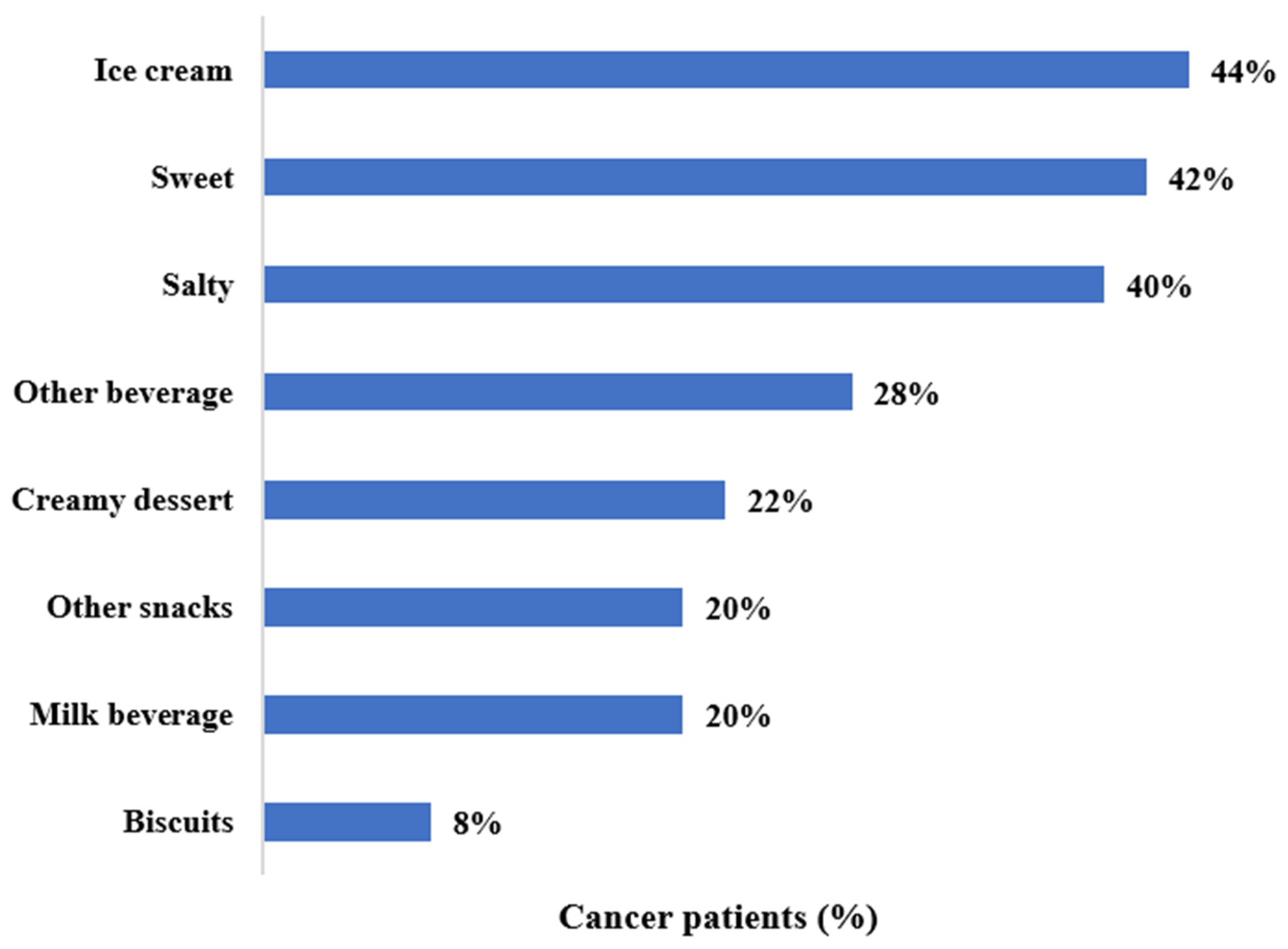

3.2. Treatment Side Effects, Important Food Attributes and Preferences

3.3. Qualitative Findings

3.3.1. Theme 1: Spiral of Side Effects

“Ah, the thing is, I take so many pills that I don’t, that everything…you get one pill for something and then they give you something else and they give you a pill for that…and it’s just never ending. So, I never know which one is giving what so that’s, that’s the only thing that I research a lot ah, possible side effects.”—Damien

“I mean everything is about strength of side effects, then you take something for that side effect and then, you know, you get another side effect from that and…”

“Oh, yes, the vomiting, nauseousness [sic], loss of hair, fatigue. Of course you’re gonna have fatigue with cancer, and yeah. We expected them. I went through it three years ago, so I kinda knew what he was gonna do, and he did too, because he was my caregiver, so we were kind of blessed that way (laughs), you know?”—Lenora

“He has side effects…Mostly cramps, fatigue, some pain—he don’t sleep very well. He’s depressed…I think my role is to support him…Try to help him hang on.”—Douglas

3.3.2. Theme 2: Pain of Eating

“So, when I swallow, it was like forcing a ball in my mouth you know, and like ripping my throat. And I became leery about how I would swallow and what I would swallow. Um…and the tear begins to keep going on and I took pain pills.”

“You know, they said it was like guaranteed that I would like go through these symptoms, especially since I am being treated for my tongue too, back part of my tongue. The ah, ah then it would make ah, ah large difference you know in my eating and my swallowing you know, and it came out to be true.”

“His taste has completely left, he has no taste. Um, extremely dry mouth. A lot of pain swallowing, the skin is starting to turn colors. He has lost a lot of weight I’d say. He started out at 210, he’s 197 now. And the doctor is like ‘No! Beef him up and…’ Let’s see what else… Irritable (laughs). Oh—and he’s got the ulcers, he has the open ulcers in the mouth. They warned us… but it’s nothing like actually going through it.”—Janice

3.3.3. Theme 3: Burden of Eating

“We don’t have normal appetite because he doesn’t.”—Douglas

“The first time I really ever felt any effect, physiologically from treatments or my cancer or anything, was the stem cell transplant I had a year ago. And that…they told me going in that they said it would be it would be it would be a rough experience for me, you know, to get through there. I can remember uh…losing my appetite and…which, which was…I mean I like food…so losing my appetite was something I didn’t cherish at all. And food just sort of it just lost its appeal you know from a nutrition standpoint.”—Roy

“I’m starting to feel defeated. Because I’m like if you lose any more weight, you know, and I’m so afraid for this, it’s like—he is doing the best he can. He’s eating. He is eating. He’s just not eating as much. He went from eating a whole bowl of oatmeal, to a half a bowl, to now it’s a couple of bites. I’ll just drink an Ensure and I’ll be alright and I’m watching this. And in his mind, he’s eating a lot, he’s doing great. And I’m like “Really?” (laughs)…you’re losing weight. I’m worried. I’m starting to worry. I just don’t know what else to do.”—Janice

3.3.4. Theme 4: Loss of Taste/Change in Taste

“Well the thing they did not they did not…they did not clue me on ahead of time was that the low dose radiation would wipe out my taste buds. For, for a significant period of time, probably, a good month or 6 weeks. That’s tough! It’s tough to lose your ability to taste food. You know, I mean pile that on top of questionable appetite you know…That—I wasn’t expecting and that was probably, through all of this, I’d have to say, through all the fatigue, fatigue and everything I can handle it, but the inability to taste food properly, and then when the buds came back. It came back in waves like salt, you know so everything tasted salty you know, or bitter, or lack of sweet sense, and so you’d eat something that’s supposed to be nice and sweet and yummy and you know it’s just ‘psst’. I’ll tell you it’s a really, really, really tough time.—Roy

“I would try to eat something different at every day just to see if something ah, made sense, if something changed. Ah, there was this different taste I could catch from something in the…I tried, I tried, but it didn’t happen. Nothing would taste…like anything.”—Damien

“It started out with everything tasted like metal for a couple weeks. And now, since last week, he has zero taste (laughs). Unless it’s super strong, like if he eats something that has citric acid, he’ll taste a twinge of it or if it’s super spicy. Other than that, he has zero taste. So, I try my best—‘You got to try to imagine it, try to imagine it… Eat with your eyes.’ But that doesn’t work, of course. So I just say—‘Just let it go down. When your stomach feels full, stop.’ (Laughs). But it’s like—trying to get him to want to eat. And he says ‘Well what’s the point? I can’t taste it.’ And I say ‘Because you have to eat.’ So, because he doesn’t even want to eat now, that’s the problem I’m dealing with now. But now, they’re threatening him with-- if you lose any more weight, you’re going to get a feeding tube. So now it’s like ‘Give me potatoes!’ (laughs).”—Janice

3.3.5. Theme 5: Symptom Management

“They just recommended that kids like Doritos because they have a strong taste, so that, that (laughs) was like the only thing that kids would eat cause it, ah, ah…I don’t know, it has a strong taste so that, that would make them taste a little bit, but ah…There was, there was nothing you could do about it, about not having taste buds…”

Interviewer: “Did you try the Doritos?”

“I think I did (laughs)…”

Interviewer: “Could you taste them?”

“No.”

“Yeah, they offered some—you know, the first thing is—well, first off, if I back up, she had some constipation, because of the pain they did give her a little oxycodone, very small amounts, which constipated her. So, they gave her Colace. So, their basic thing is to drug it and then the diarrhea, they were saying the Imodium. But we did talk to the naturopath there who we really respect and she really respects, I mean, cause she—they talk their own lingo, so they’re—so the naturopath has been very helpful because her thing is food and things.”

3.3.6. Theme 6: Solutions

“For the bone, she was taking (stutters) some joint support, some (pause) different herbs and things like that and it’s a whole—it’s about 30 some herbs and stuff, but she was taking a lot of that. She was taking some stuff to build up the blood. She was taking some stuff to, like—guava and some other things that would help attack the cancer. So she was doing a lot of herbal stuff to actually attack and treat the cancer that was non- “medicinal” and this was prior to getting (stutters) the herbs.”—Michael

“I’m thinking the bone broth and then protein shakes rather than that Ensure refrigerator. [Laughs] Yeah. We’re both not into the Ensure, that’s for sure. Although she was because part of her problem before she was diagnosed was she was having trouble eating. So, she was eating—she was downing Slimfast shakes because she was forcing herself to eat something. And you know, I’m like, let me make these shakes for you. They’re good, you know. It’s plant-based protein and coconut oil, fruits and greens. So, she has had those with me and she is open to that. I said, ‘Before you drink anything like that other stuff, please let me just do this with you.’ [Laughs]”—Beth

4. Discussion

- Caregiver empathy and sharing experience of treatment

- Complementary and alternative medicine in conflict with traditional oncology protocols

- Be warned, but you’re on your own to figure this out

4.1. Through-Line A: Caregiver Empathy and Sharing Experience of Treatment

4.2. Through-Line B: Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Conflict with Traditional Oncology Protocols

4.3. Through-Line C: Be Warned, but You’re on Your Own to Figure This Out

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Cancer Institute. Prostate Cancer, Nutrition, and Dietary Supplements (PDQ®): Health Professional Version; PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2017. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26389500 (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Henry, D.H.; Viswanathan, H.N.; Elkin, E.P.; Traina, S.; Wade, S.; Cella, D. Symptoms and treatment burden associated with cancer treatment: Results from a cross-sectional national survey in the U.S. Support. Care Cancer 2008, 16, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coa, K.I.; Epstein, J.B.; Ettinger, D.; Jatoi, A.; McManus, K.; Platek, M.E.; Price, W.; Stewart, M.; Teknos, T.N.; Moskowitz, B. The impact of cancer treatment on the diets and food preferences of patients receiving outpatient treatment. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 67, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pearce, A.; Haas, M.; Viney, R.; Pearson, S.A.; Haywood, P.; Brown, C.; Ward, R. Incidence and severity of self-reported chemotherapy side effects in routine care: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Cancer. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0. 2009. Available online: https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03/Archive/CTCAE_4.0_2009-05-29_QuickReference_8.5x11.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Guerdoux-Ninot, E.; Kilgour, R.D.; Janiszewski, C.; Jarlier, M.; Meuric, J.; Poirée, B.; Buzzo, S.; Ninot, G.; Courraud, J.; Wismer, W.; et al. Meal context and food preferences in cancer patients: Results from a French self-report survey. Springerplus 2016, 5, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Drareni, K.; Bensafi, M.; Giboreau, A.; Dougkas, A. Chemotherapy-induced taste and smell changes influence food perception in cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 2125–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltong, A.; Aranda, S.; Keast, R.; Wynne, R.; Francis, P.A.; Chirgwin, J.; Gough, K. A prospective cohort study of the effects of adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy on taste function, food liking, appetite and associated nutritional outcomes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Snchez-Lara, K.; Sosa-Snchez, R.; Green-Renner, D.; Rodríguez, C.; Laviano, A.; Motola-Kuba, D.; Arrieta, O. Influence of taste disorders on dietary behaviors in cancer patients under chemotherapy. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Belqaid, K.; Tishelman, C.; McGreevy, J.; Månsson-Brahme, E.; Orrevall, Y.; Wismer, W.; Bernhardson, B.M. A longitudinal study of changing characteristics of self-reported taste and smell alterations in patients treated for lung cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 21, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Vries, V.C.; van den Berg, M.M.G.A.; de Vries, J.H.M.; Boesveldt, S.; de Kruif, J.T.C.; Buist, N.; Haringhuizen, A.; Los, M.; Sommeijer, D.W.; Timmer-Bonte, J.H.N.; et al. Differences in dietary intake during chemotherapy in breast cancer patients compared to women without cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2017, 25, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nolden, A.A.; Hwang, L.D.; Boltong, A.; Reed, D.R. Chemosensory changes from cancer treatment and their effects on patients’ food behavior: A scoping review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ponticelli, E.; Clari, M.; Frigerio, S.; De Clemente, A.; Bergese, I.; Scavino, E.; Bernardini, A.; Sacerdote, C. Dysgeusia and health-related quality of life of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, K.; Morita, T.; Koshimoto, S.; Uno, T.; Katayama, H.; Tatara, R. Eating-related distress in advanced cancer patients with cachexia and family members: A survey in palliative and supportive care settings. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardson, B.M.; Tishelman, C.; Rutqvist, L.E. Taste and smell changes in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy: Distress, impact on daily life, and self-care strategies. Cancer Nurs. 2009, 32, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guigni, B.A.; Callahan, D.M.; Tourville, T.W.; Miller, M.S.; Fiske, B.; Voigt, T.; Korwin-Mihavics, B.; Anathy, V.; Dittus, K.; Toth, M.J. Skeletal muscle atrophy and dysfunction in breast cancer patients: Role for chemotherapy-derived oxidant stress. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2018, 315, C744–C756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattox, T.W. Cancer Cachexia: Cause, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2017, 32, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurgali, K.; Jagoe, R.T.; Abalo, R. Editorial: Adverse effects of cancer chemotherapy: Anything new to improve tolerance and reduce sequelae? Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurkcu, M.; Meijer, R.I.; Lonterman, S.; Muller, M.; de van der Schueren, M.A.E. The association between nutritional status and frailty characteristics among geriatric outpatients. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2018, 23, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Nyunt, M.S.Z.; Gao, Q.; Wee, S.L.; Ng, T.P. Frailty and Malnutrition: Related and Distinct Syndrome Prevalence and Association among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, C.; Salameh, P.; Barberger-Gateau, P. Malnutrition and frailty in community dwelling older adults living in a rural setting. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Harhay, M.O.; Harhay, M.N. The Prognostic Importance of Frailty in Cancer Survivors. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 2538–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, J.X.; Akinyemiju, T.; Bartolucci, A.; Wang, H.E.; Waterbor, J.; Griffin, R. Mediating Effects of Frailty Indicators on the Risk of Sepsis After Cancer. J. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 35, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregiving in the United States. 2020. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/ppi/info-2020/caregiving-in-the-united-states.html (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Schulz, R.; Tompkins, C.A. Informal Caregivers in the United States: Prevalence, Caregiver Characteristics, and Ability to Provide Care. In The Role of Human Factors in Home Health Care: Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Litzelman, K. Caregiver Well-being and the Quality of Cancer Care. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 35, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryn, M.; Sanders, S.; Kahn, K.; Van Houtven, C.; Griffin, J.M.; Martin, M.; Atienza, A.A.; Phelan, S.; Finstad, D.; Rowland, J. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: A hidden quality issue? Psycho-Oncol. 2011, 20, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQuestion, M.; Fitch, M.; Howell, D. The changed meaning of food: Physical, social and emotional loss for patients having received radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2011, 15, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, J.B. Food connections: A qualitative exploratory study of weight- and eating-related distress in families affected by advanced cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 20, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lize, N.; Raijmakers, N.; van Lieshout, R.; Youssef-El Soud, M.; van Limpt, A.; van der Linden, M.; Beijer, S. Psychosocial consequences of a reduced ability to eat for patients with cancer and their informal caregivers: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 49, 101838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, S.C.; Gillath, O. How food brings us together: The ties between attachment and food behaviors. Appetite 2020, 151, 104654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziker, J.; Schnegg, M. Food sharing at meals. Hum. Nat. 2005, 16, 178–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeggi, A.V.; Van Schaik, C.P. The evolution of food sharing in primates. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2011, 65, 2125–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamburg, M.E.; Finkenauer, C.; Schuengel, C. Food for love: The role of food offering in empathic emotion regulation. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marshall, D. Food as ritual, routine or convention. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2005, 8, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.W.; Anderson, A.S. Proper meals in transition: Young married couples on the nature of eating together. Appetite 2002, 39, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.; Rozin, P.; Fiske, A.P. Food sharing and feeding another person suggest intimacy; two studies of american college students. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quandt, S.A.; Arcury, T.A.; Bell, R.A.; McDonald, J.; Vitolins, M.Z. The social and nutritional meaning of food sharing among older rural adults. J. Aging Stud. 2001, 15, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam (accessed on 23 December 2021).

- Horneber, M.; Bueschel, G.; Dennert, G.; Less, D.; Ritter, E.; Zwahlen, M. How Many Cancer Patients Use Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2012, 11, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahall, M. Prevalence, patterns, and perceived value of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients: A cross-sectional, descriptive study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wode, K.; Henriksson, R.; Sharp, L.; Stoltenberg, A.; Hök Nordberg, J. Cancer patients’ use of complementary and alternative medicine in Sweden: A cross-sectional study. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Findlay, M.; Rankin, N.M.; Bauer, J.; Collett, G.; Shaw, T.; White, K. Completely and utterly flummoxed and out of my depth’: Patient and caregiver experiences during and after treatment for head and neck cancer—A qualitative evaluation of barriers and facilitators to best-practice nutrition care. Support. Care Cancer 2020, 28, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardson, B.M.; Tishelman, C.; Rutqvist, L.E. Chemosensory Changes Experienced by Patients Undergoing Cancer Chemotherapy: A Qualitative Interview Study. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2007, 34, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cancer Patients (N = 50) | Caregivers (N = 52) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 21 (42.00%) | 42 (80.77%) | |

| Male | 29 (58.00%) | 10 (19.23%) | |

| Age Range, n (%) | |||

| 18–54 years | 9 (18.00%) | 15 (28.85%) | |

| 55+ | 41 (82.00%) | 37 (71.15%) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| African American | 9 (19.15%) | 2 (4.00%) | |

| Caucasian | 38 (80.85%) | 44 (88.00%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 4 (8.00%) | |

| Hispanic or Latino, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 3 (6.38%) | 3 (5.77%) | |

| No | 44 (93.62%) | 49 (94.23%) | |

| Level of Education, n (%) (Grouped) | |||

| HS Graduate or less | 12 (24.00%) | 6 (11.54%) | |

| Some college | 7 (14.00%) | 11 (21.15%) | |

| College or greater | 31 (62.00%) | 35 (67.31%) | |

| Adequate Financial Support, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 40 (80.00%) | 44 (84.62%) | |

| No | 10 (20.00%) | 8 (15.38%) | |

| Personal Characteristics | |||

| Cancer type, n (%) | |||

| GI cancer | 8 (16.67%) | ||

| Head, Neck or Lung | 10 (20.83%) | ||

| Hematologic Cancers | 10 (20.83%) | ||

| Other Solid | 20 (41.67%) | ||

| Absence due to Trt or Role, n (%) | |||

| None or NA | 34 (70.83%) | 33 (66.00%) | |

| 1–9 days | 2 (4.17%) | 11 (22.00%) | |

| 10+ Days | 12 (25.00%) | 6 (12.00%) | |

| Average number days per week caregiving | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7 (5, 7) | ||

| Range | 0, 7 | ||

| Averagenumber hours per day caregiving | |||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (2.5, 10) | ||

| Range | 0, 24 | ||

| Side Effects Reported | Cancer Patients (N = 50) * |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | 29 (58.00%) |

| Dry mouth | 15 (30.00%) |

| Nausea | 12 (24.00%) |

| Constipation | 10 (20.00%) |

| Diarrhea | 10 (20.00%) |

| Swallowing difficulties | 8 (16.00%) |

| Mouth ulcers | 8 (16.00%) |

| Persistent taste | 7 (14.00%) |

| Other | 6 (12.00%) |

| Chewing difficulties | 4 (8.00%) |

| Hypersensitivity to odors | 4 (8.00%) |

| Vomiting | 2 (4.00%) |

| Interference/disturbance of eating and drinking due to side effects (If Yes to side-effect experienced question) (N = 36) | |

| Yes | 22 (61.11%) |

| No | 14 (38.89%) |

| Themes | Examples |

|---|---|

| Spiral of side effects | “He has side effects…Mostly cramps, fatigue, some pain—he don’t sleep very well. He’s depressed…I think my role is to support him…Try to help him hang on.”—Douglas |

| “Ah, the thing is, I take so many pills that I don’t, that everything…you get one pill for something and then they give you something else and they give you a pill for that…and it’s just never ending. So, I never know which one is giving what so that’s, that’s the only thing that I research a lot ah, possible side effects.”—Damien | |

| “I mean everything is about strength of side effects, then you take something for that side effect and then, you know, you get another side effect from that and…”—Alfred | |

| “Oh, yes, the vomiting, nauseousness, loss of hair, fatigue. Of course you’re gonna have fatigue with cancer, and yeah. We expected them. I went through it three years ago, so I kinda knew what he was gonna do, and he did too, because he was my caregiver, so we were kind of blessed that way (laughs), you know?”—Lenora | |

| So, they don’t actually tell you everything. Well, they weren’t surprised, but I think was and I would say, “what’s this” and they would say, “well, we did touch on that a little bit”. Well, if they touched on it, I was sleeping or (laughing)—my chemo didn’t hear it.—Susan | |

| “They told me all the side effects and they gave me a ton of pills and every time I had this effect, they took that pill; then, when I had that effect, they took that pill.”—Henry | |

| Pain of eating | “So, when I swallow, it was like forcing a ball in my mouth you know, and like ripping my throat. And I became leery about how I would swallow and what I would swallow. Um…and the tare begins to keep going on and I took pain pills.”—John |

| “His taste has completely left, he has no taste. Um, extremely dry mouth. A lot of pain swallowing, the skin is starting to turn colors. He has lost a lot of weight I’d say. He started out at 210, he’s 197 now. And the doctor is like “No! Beef him up and…” Let’s see what else…Irritable (laughs), quick.” | |

| “Oh—and he’s got the ulcers, he has the open ulcers in the mouth. They warned us…but it’s nothing like actually going through it.”—Janice | |

| “You know, they said it was like guaranteed that I would like go through these symptoms, especially since I am being treated for my tongue too, back part of my tongue. The ah, ah then it would make ah, ah large difference you know in my eating and my swallowing you know, and it came out to be true.”—John | |

| “The chemo gives him the cold. You can’t touch cold, so he has to drink room temp, and if not, he can feel it in his throat. I don’t know how to describe it. When I had it, it felt like you’re swallowing glass. His hasn’t come to that yet, but his hands and feet and that, when he touches cold, it affects him, and that’s from the chemo, and we’re expecting that.”—Lenora | |

| Burden of eating | “The first time I really ever felt any effect, physiologically from treatments or my cancer or anything, was the stem cell transplant I had a year ago. And and that…they told me going in that they said it would be it would be it would be a rough experience for me, you know, to get through there. I can remember uh…losing my appetite and…which, which was…I mean I like food…so losing my appetite was something I didn’t cherish at all. And food just sort of it just lost its appeal you know from a nutrition standpoint.”—Roy |

| “We don’t have normal appetite because he doesn’t (either).”—Douglas | |

| “I’m starting to feel defeated. Because I’m like if you lose any more weight, you know, and I’m so afraid for this, it’s like—he is doing the best he can. He’s eating. He is eating. He’s just not eating as much. He went from eating a whole bowl of oatmeal, to a half a bowl, to now it’s a couple of bites. I’ll just drink an Ensure and I’ll be alright and I’m watching this. And in his mind, he’s eating a lot, he’s doing great. And I’m like “Really?” (laughs)…you’re losing weight. I’m worried. I’m starting to worry. I just don’t know what else to do.”—Janice | |

| Loss of taste/change in taste | “It started out with everything tasted like metal for a couple weeks. And now, since last week, he has zero taste (laughs). Unless it’s super strong, like if he eats something that has citric acid, he’ll taste a twinge of it or if it’s super spicy. Other than that, he has zero taste. So, I try my best—‘You got to try to imagine it, try to imagine it. Eat with your eyes. But that doesn’t work, of course. So I just say—‘Just let it go down. When your stomach feels full, stop.’ (Laughs). But it’s like—trying to get him to want to eat. And he says ‘Well what’s the point? I can’t taste it.’ And I say ‘Because you have to eat.’ So, because he doesn’t even want to eat now, that’s the problem I’m dealing with now. But now, they’re threatening him with—if you lose any more weight, you’re going to get a feeding tube. So now it’s like ‘Give me potatoes!’ (laughs).”—Janice |

| “I would try to eat something different at every day just to see if something ah, made sense, if something changed. Ah, there was this different taste I could catch from something in the…I tried, I tried, but it didn’t happen. Nothing would taste…like anything.”—Damien | |

| “Well the thing they did not they did not…they did not clue me on ahead of time was that the low dose radiation would wipe out my taste buds. For, for a significant period of time, probably, a good month or 6 weeks. That’s tough! It’s tough to lose your ability to taste food. You know, I mean pile that on top of questionable appetite you know…That I wasn’t expecting and that was probably, through all of this, I’d have to say, through all the fatigue, fatigue and everything I can handle it, but the inability to taste food properly, and then when the buds came back. It came back in waves like salt, you know so everything tasted salty you know, or bitter, or lack of sweet sense, and so you’d eat something that’s supposed to be nice and sweet and yummy and you know it’s just ‘psst’. I’ll tell you it’s a really, really, really tough time.—Roy | |

| Symptom management | “They just recommended that kids like Doritos because they have a strong taste, so that, that (laughs) was like the only thing that kids would eat cause it, ah, ah…I don’t know, it has a strong taste so that, that would make them taste a little bit, but ah…There was, there was nothing you could do about it, about not having taste buds…” Interviewer: “Did you try the Doritos?” “I think I did (laughs)…” Interviewer: “Could you taste them?” No.”—Damien |

| “Yeah, they offered some—you know, the first thing is—well, first off, if I back up, she had some constipation, because of the pain they did give her a little oxycodone, very small amounts, which constipated her. So, they gave her Colace. So, their basic thing is to drug it and then the diarrhea, they were saying the Imodium. But we did talk to the naturopath there who we really respect and she really respects, I mean ’cause she—they talk their own lingo, so they’re—so the naturopath has been very helpful because her thing is food and things.”—Michael | |

| “So—and the truth is, as far as pain goes, when we got to the hospital in December, before—when we just—and the doctors kind of said—we didn’t meet the naturopath, that was the only one we didn’t meet, unfortunately, and they told her to stop all the herbs, she walked in, she couldn’t walk out. The pain had increased. When she started just saying screw it, I’m gonna start taking the herbs actually decreased her pain, and we’re talking like 8 to 10 down to like a 3 to 4 pain.”—Michael | |

| “The hair loss, I mean that really isn’t a problem. The fatigue that really hasn’t been a problem either because they suggested ways to break that so the main one we have been doing is, my wife and I have been walking maybe we would walk different trails or around the closest neighborhood, I would say about a half hour each day just to stay active and that’s really helped fight off the fatigue.”—Carter | |

| “But her pain is much more intense now in the evening and in the middle of the night and stuff, and it wakes her up and, you know, sometimes she is like screaming in pain and stuff like that. And so I think activity keeps you off of the pain. When you’re inactive and you’re not doing anything then you can dwell on it. And I also think you dwell on it, you know, in a negative way because it hurts, it hurts, it hurts, and you can’t distract yourself from it.”—Michael | |

| Solutions | “For the bone, she was taking (stutters) some joint support, some (pause) different herbs and things like that and it’s a whole—it’s about 30 some herbs and stuff, but she was taking a lot of that. She was taking some stuff to build up the blood. She was taking some stuff to, like—guava and some other things that would help attack the cancer. So she was doing a lot of herbal stuff to actually attack and treat the cancer that was non- “medicinal” and this was prior to getting (stutters) the herbs.”—Michael |

| “I just have to force it on him, and remind him. I tell him “it’s breakfast”—because we’re on a schedule—“It’s lunch, it’s dinner.” I became more forceful with him. Before I was—you do what you gotta do. But now I’m the one that’s more forceful. And, I try to make things a bit more seasoned, than I would normally do, because hopefully he’d be able to taste it (laughs). And then he’s throwing it out because he doesn’t want to eat it all. So now I’m starting to feel bad about that. Now you’re wasting food. I don’t know…I just keep asking for tips and hints on the internet, the doctors, somebody give me some tips. Because I don’t know what else to do, because he’s not eating.”—Janice | |

| “I’m thinking the bone broth and then protein shakes rather than that Ensure refrigerator. [Laughs] Yeah. We’re both not into the Ensure, that’s for sure. Although she was because part of her problem before she was diagnosed was she was having trouble eating. So, she was eating—she was downing Slimfast shakes because she was forcing herself to eat something. And you know, I’m like, let me make these shakes for you. They’re good, you know. It’s plant-based protein and coconut oil, fruits and greens. So, she has had those with me and she is open to that. I said, ‘Before you drink anything like that other stuff, please let me just do this with you.’ [Laughs]”—Beth |

| Through-Lines | Examples |

|---|---|

| Caregiver empathy and sharing experience of treatment | “I’m thinking the bone broth and then protein shakes rather than that Ensure refrigerator. [Laughs] Yeah. We’re both not into the Ensure, that’s for sure. Although she was because part of her problem before she was diagnosed was she was having trouble eating. So, she was eating—she was downing Slimfast shakes because she was forcing herself to eat something. And you know, I’m like, let me make these shakes for you. They’re good, you know. It’s plant-based protein and coconut oil, fruits and greens. So, she has had those with me and she is open to that. I said, ‘Before you drink anything like that other stuff, please let me just do this with you.’ [Laughs]”—Beth |

| “I just have to force it on him, and remind him. I tell him “it’s breakfast”—because we’re on a schedule—“It’s lunch, it’s dinner.” I became more forceful with him. Before I was—you do what you gotta do. But now I’m the one that’s more forceful. And, I try to make things a bit more seasoned, than I would normally do, because hopefully he’d be able to taste it (laughs). And then he’s throwing it out because he doesn’t want to eat it all. So now I’m starting to feel bad about that. Now you’re wasting food. I don’t know…I just keep asking for tips and hints on the internet, the doctors, somebody give me some tips. Because I don’t know what else to do, because he’s not eating.”—Janice | |

| “But her pain is much more intense now in the evening and in the middle of the night and stuff, and it wakes her up and, you know, sometimes she is like screaming in pain and stuff like that. And so I think activity keeps you off of the pain. When you’re inactive and you’re not doing anything then you can dwell on it. And I also think you dwell on it, you know, in a negative way because it hurts, it hurts, it hurts, and you can’t distract yourself from it.”—Michael | |

| “The hair loss, I mean that really isn’t a problem. The fatigue that really hasn’t been a problem either because they suggested ways to break that so the main one we have been doing is, my wife and I have been walking maybe we would walk different trails or around the closest neighborhood, I would say about a half hour each day just to stay active and that’s really helped fight off the fatigue.”—Carter | |

| “Yeah, they offered some—you know, the first thing is—well, first off, if I back up, she had some constipation, because of the pain they did give her a little oxycodone, very small amounts, which constipated her. So, they gave her Colace. So, their basic thing is to drug it and then the diarrhea, they were saying the Imodium. But we did talk to the naturopath there who we really respect and she really respects, I mean ’cause she—they talk their own lingo, so they’re—so the naturopath has been very helpful because her thing is food and things.”—Michael | |

| “It started out with everything tasted like metal for a couple weeks. And now, since last week, he has zero taste (laughs). Unless it’s super strong, like if he eats something that has citric acid, he’ll taste a twinge of it or if it’s super spicy. Other than that, he has zero taste. So, I try my best—‘You got to try to imagine it, try to imagine it. Eat with your eyes.’ But that doesn’t work, of course. So I just say—‘Just let it go down. When your stomach feels full, stop.’ (Laughs). But it’s like—trying to get him to want to eat. And he says ‘Well what’s the point? I can’t taste it.’ And I say ‘Because you have to eat.’ So, because he doesn’t even want to eat now, that’s the problem I’m dealing with now. But now, they’re threatening him with-- if you lose any more weight, you’re going to get a feeding tube. So now it’s like ‘Give me potatoes!’ (laughs).”—Janice | |

| “I’m starting to feel defeated. Because I’m like if you lose any more weight, you know, and I’m so afraid for this, it’s like—he is doing the best he can. He’s eating. He is eating. He’s just not eating as much. He went from eating a whole bowl of oatmeal, to a half a bowl, to now it’s a couple of bites. I’ll just drink an Ensure and I’ll be alright and I’m watching this. And in his mind, he’s eating a lot, he’s doing great. And I’m like “Really?” (laughs)…you’re losing weight. I’m worried. I’m starting to worry. I just don’t know what else to do.”—Janice | |

| “We don’t have normal appetite because he doesn’t (either).”—Douglas | |

| “The chemo gives him the cold. You can’t touch cold, so he has to drink room temp, and if not, he can feel it in his throat. I don’t know how to describe it. When I had it, it felt like you’re swallowing glass. His hasn’t come to that yet, but his hands and feet and that, when he touches cold, it affects him, and that’s from the chemo, and we’re expecting that.”—Lenora | |

| “His taste has completely left, he has no taste. Um, extremely dry mouth. A lot of pain swallowing, the skin is starting to turn colors. He has lost a lot of weight I’d say. He started out at 210, he’s 197 now. And the doctor is like “No! Beef him up and…” Let’s see what else…Irritable (laughs), quick.” “Oh—and he’s got the ulcers, he has the open ulcers in the mouth. They warned us…but it’s nothing like actually going through it.”—Janice | |

| “Oh, yes, the vomiting, nauseousness, loss of hair, fatigue. Of course you’re gonna have fatigue with cancer, and yeah. We expected them. I went through it three years ago, so I kinda knew what he was gonna do, and he did too, because he was my caregiver, so we were kind of blessed that way (laughs), you know?”—Lenora | |

| “He has side effects…Mostly cramps, fatigue, some pain—he don’t sleep very well. He’s depressed…I think my role is to support him…Try to help him hang on.”—Douglas | |

| Complementary and alternative medicine in conflict with traditional oncology protocols | “Yeah, they offered some—you know, the first thing is—well, first off, if I back up, she had some constipation, because of the pain they did give her a little oxycodone, very small amounts, which constipated her. So, they gave her Colace. So, their basic thing is to drug it and then the diarrhea, they were saying the Imodium. But we did talk to the naturopath there who we really respect and she really respects, I mean ’cause she—they talk their own lingo, so they’re—so the naturopath has been very helpful because her thing is food and things.”—Michael |

| “For the bone, she was taking (stutters) some joint support, some (pause) different herbs and things like that and it’s a whole—it’s about 30 some herbs and stuff, but she was taking a lot of that. She was taking some stuff to build up the blood. She was taking some stuff to, like—guava and some other things that would help attack the cancer. So she was doing a lot of herbal stuff to actually attack and treat the cancer that was non- “medicinal” and this was prior to getting (stutters) the herbs.”—Michael | |

| “So—and the truth is, as far as pain goes, when we got to the hospital in December, before—when we just—and the doctors kind of said—we didn’t meet the naturopath, that was the only one we didn’t meet, unfortunately, and they told her to stop all the herbs, she walked in, she couldn’t walk out. The pain had increased. When she started just saying screw it, I’m gonna start taking the herbs actually decreased her pain, and we’re talking like 8 to 10 down to like a 3 to 4 pain.”—Michael | |

| “I just have to force it on him, and remind him. I tell him “it’s breakfast”—because we’re on a schedule—“It’s lunch, it’s dinner.” I became more forceful with him. Before I was—you do what you gotta do. But now I’m the one that’s more forceful. And, I try to make things a bit more seasoned, than I would normally do, because hopefully he’d be able to taste it (laughs). And then he’s throwing it out because he doesn’t want to eat it all. So now I’m starting to feel bad about that. Now you’re wasting food. I don’t know…I just keep asking for tips and hints on the internet, the doctors, somebody give me some tips. Because I don’t know what else to do, because he’s not eating.”—Janice | |

| “I’m thinking the bone broth and then protein shakes rather than that Ensure refrigerator. [Laughs] Yeah. We’re both not into the Ensure, that’s for sure. Although she was because part of her problem before she was diagnosed was she was having trouble eating. So, she was eating—she was downing Slimfast shakes because she was forcing herself to eat something. And you know, I’m like, let me make these shakes for you. They’re good, you know. It’s plant-based protein and coconut oil, fruits and greens. So, she has had those with me and she is open to that. I said, ‘Before you drink anything like that other stuff, please let me just do this with you.’ [Laughs]”—Beth | |

| Be warned, but you’re on your own to figure this out | “They just recommended that kids like Doritos because they have a strong taste, so that, that (laughs) was like the only thing that kids would eat cause it, ah, ah…I don’t know, it has a strong taste so that, that would make them taste a little bit, but ah…There was, there was nothing you could do about it, about not having taste buds…” Interviewer: “Did you try the Doritos?” “I think I did (laughs)…” Interviewer: “Could you taste them?” “No.”—Damien |

| “I would try to eat something different at every day just to see if something ah, made sense, if something changed. Ah, there was this different taste I could catch from something in the…I tried, I tried, but it didn’t happen. Nothing would taste…like anything.”—Damien | |

| “I’m thinking the bone broth and then protein shakes rather than that Ensure refrigerator. [Laughs] Yeah. We’re both not into the Ensure, that’s for sure. Although she was because part of her problem before she was diagnosed was she was having trouble eating. So, she was eating—she was downing Slimfast shakes because she was forcing herself to eat something. And you know, I’m like, let me make these shakes for you. They’re good, you know. It’s plant-based protein and coconut oil, fruits and greens. So, she has had those with me and she is open to that. I said, ‘Before you drink anything like that other stuff, please let me just do this with you.’ [Laughs]”—Beth | |

| “I just have to force it on him, and remind him. I tell him “it’s breakfast”—because we’re on a schedule—“It’s lunch, it’s dinner.” I became more forceful with him. Before I was—you do what you gotta do. But now I’m the one that’s more forceful. And, I try to make things a bit more seasoned, than I would normally do, because hopefully he’d be able to taste it (laughs). And then he’s throwing it out because he doesn’t want to eat it all. So now I’m starting to feel bad about that. Now you’re wasting food. I don’t know…I just keep asking for tips and hints on the internet, the doctors, somebody give me some tips. Because I don’t know what else to do, because he’s not eating.”—Janice | |

| “So—and the truth is, as far as pain goes, when we got to the hospital in December, before—when we just—and the doctors kind of said—we didn’t meet the naturopath, that was the only one we didn’t meet, unfortunately, and they told her to stop all the herbs, she walked in, she couldn’t walk out. The pain had increased. When she started just saying screw it, I’m gonna start taking the herbs actually decreased her pain, and we’re talking like 8 to 10 down to like a 3 to 4 pain.”—Michael | |

| “For the bone, she was taking (stutters) some joint support, some (pause) different herbs and things like that and it’s a whole—it’s about 30 some herbs and stuff, but she was taking a lot of that. She was taking some stuff to build up the blood. She was taking some stuff to, like—guava and some other things that would help attack the cancer. So she was doing a lot of herbal stuff to actually attack and treat the cancer that was non—“medicinal” and this was prior to getting (stutters) the herbs.”—Michael | |

| “But her pain is much more intense now in the evening and in the middle of the night and stuff, and it wakes her up and, you know, sometimes she is like screaming in pain and stuff like that. And so I think activity keeps you off of the pain. When you’re inactive and you’re not doing anything then you can dwell on it. And I also think you dwell on it, you know, in a negative way because it hurts, it hurts, it hurts, and you can’t distract yourself from it.”—Michael | |

| “It started out with everything tasted like metal for a couple weeks. And now, since last week, he has zero taste (laughs). Unless it’s super strong, like if he eats something that has citric acid, he’ll taste a twinge of it or if it’s super spicy. Other than that, he has zero taste. So, I try my best—‘You got to try to imagine it, try to imagine it. Eat with your eyes.’ But that doesn’t work, of course. So I just say—‘Just let it go down. When your stomach feels full, stop.’ (Laughs). But it’s like—trying to get him to want to eat. And he says ‘Well what’s the point? I can’t taste it.’ And I say ‘Because you have to eat.’ So, because he doesn’t even want to eat now, that’s the problem I’m dealing with now. But now, they’re threatening him with—if you lose any more weight, you’re going to get a feeding tube. So now it’s like ‘Give me potatoes!’ (laughs).”—Janice | |

| “Well the thing they did not they did not…they did not clue me on ahead of time was that the low dose radiation would wipe out my taste buds. For, for a significant period of time, probably, a good month or 6 weeks. That’s tough! It’s tough to lose your ability to taste food. You know, I mean pile that on top of questionable appetite you know…That I wasn’t expecting and that was probably, through all of this, I’d have to say, through all the fatigue, fatigue and everything I can handle it, but the inability to taste food properly, and then when the buds came back. It came back in waves like salt, you know so everything tasted salty you know, or bitter, or lack of sweet sense, and so you’d eat something that’s supposed to be nice and sweet and yummy and you know it’s just ‘psst’. I’ll tell you it’s a really, really, really tough time.—Roy |

| Through-Lines | Key Considerations and Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Caregiver empathy and sharing experience of treatment |

|

| Complementary and alternative medicine in conflict with traditional oncology protocols |

|

| Be warned, but you’re on your own to figure this out |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milliron, B.-J.; Packel, L.; Dychtwald, D.; Klobodu, C.; Pontiggia, L.; Ogbogu, O.; Barksdale, B.; Deutsch, J. When Eating Becomes Torturous: Understanding Nutrition-Related Cancer Treatment Side Effects among Individuals with Cancer and Their Caregivers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020356

Milliron B-J, Packel L, Dychtwald D, Klobodu C, Pontiggia L, Ogbogu O, Barksdale B, Deutsch J. When Eating Becomes Torturous: Understanding Nutrition-Related Cancer Treatment Side Effects among Individuals with Cancer and Their Caregivers. Nutrients. 2022; 14(2):356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020356

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilliron, Brandy-Joe, Lora Packel, Dan Dychtwald, Cynthia Klobodu, Laura Pontiggia, Ochi Ogbogu, Byron Barksdale, and Jonathan Deutsch. 2022. "When Eating Becomes Torturous: Understanding Nutrition-Related Cancer Treatment Side Effects among Individuals with Cancer and Their Caregivers" Nutrients 14, no. 2: 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020356

APA StyleMilliron, B.-J., Packel, L., Dychtwald, D., Klobodu, C., Pontiggia, L., Ogbogu, O., Barksdale, B., & Deutsch, J. (2022). When Eating Becomes Torturous: Understanding Nutrition-Related Cancer Treatment Side Effects among Individuals with Cancer and Their Caregivers. Nutrients, 14(2), 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020356