Exploring the Determinants of Food Choice in Chinese Mainlanders and Chinese Immigrants: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim

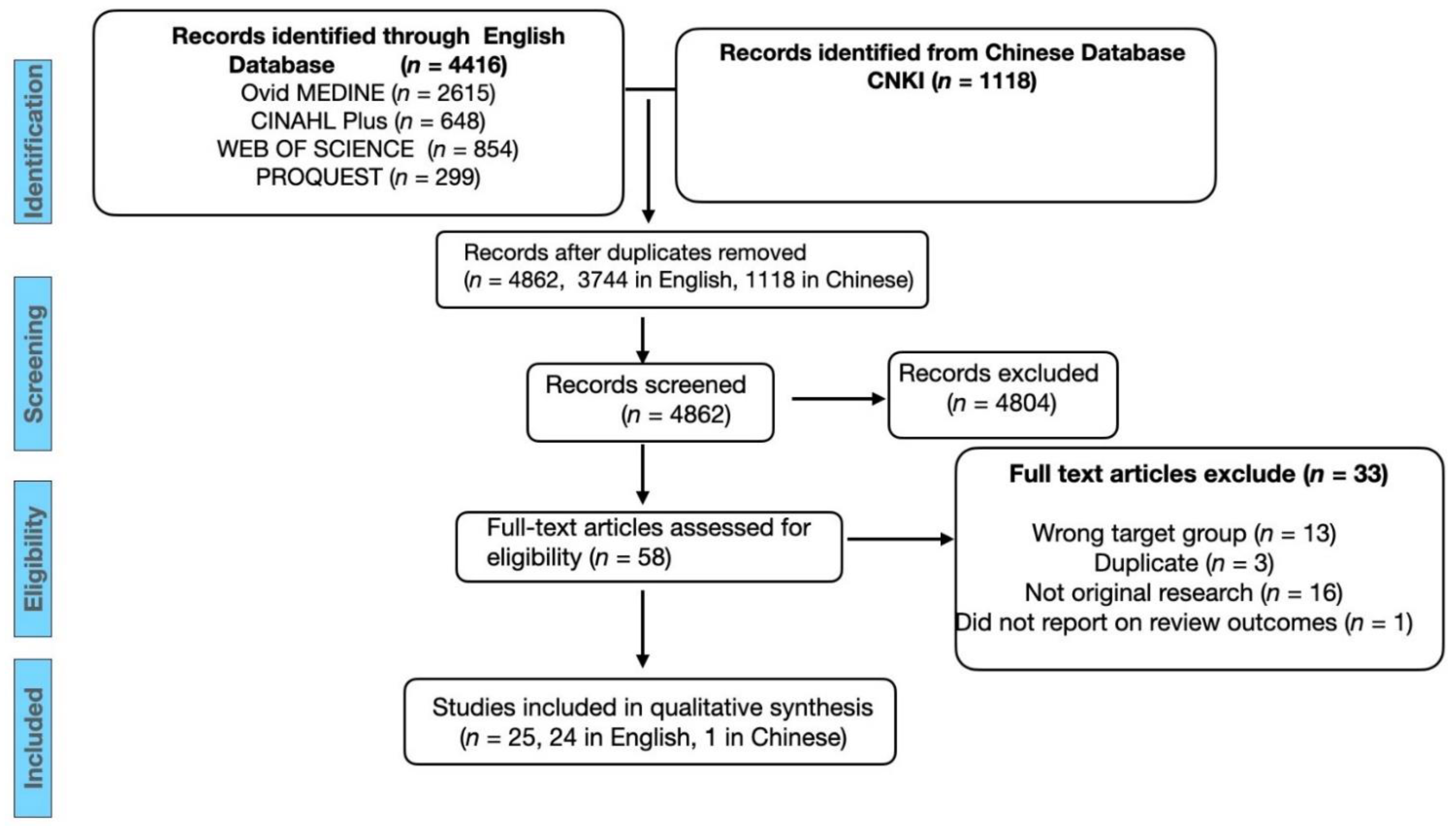

2. Method

2.1. Study Identification

2.2. Screening and Eligibility

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Methodological Quality

3.2. Qualitative Analysis of Study Findings

3.2.1. The Concept of Traditional Chinese Medicine Influences Participants’ Food Choices

3.2.2. Individual’s Perception of a Healthy Diet in Chinese Culture Influences Food Choices

3.2.3. The Desire to Maintain Harmony in Family/Community Influences Food Choices

3.2.4. Physical and Social Environmental Factors Influence Food Choices

4. Discussion

4.1. The Concept of TCM Influenced Chinese People’s Food Choice

4.2. Perceptions of a Healthy Diet in Chinese Culture Are Considered When Making Food Choices

4.3. The Desire to Maintain Harmony in Families/Communities Plays a Role in Making Food Choices

4.4. Physical and Social Environmental Factors Affected Chinese People’s Food Choices

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- -

- Asian Continental Ancestry Group/OR Chin$ OR “Emigration and Immigration”/OR

- -

- “Emigrants and Immigrants”/OR Asian Americans OR “Transients and migrants”/OR “Chinese immigra$”/OR “Chinese migra$” AND

- -

- Food preferences/OR Feeding behaviour/OR “Food choice$” OR

- -

- “Diet$ preference$” OR “Eating habits$”

- -

- “食物选择” + “饮食选择” + “膳食选择” + “食品选择” OR “饮食决策” + “膳食决策”

- -

- OR “(饮食 + 膳食) * 喜好” OR “(饮食 + 膳食) *偏好” OR “(食品 + 食物) * 购买意愿”

References

- World Health Organisation. Noncommunicable Diseases Factsheets. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Melaku, Y.A.; Renzaho, A.; Gill, T.K.; Taylor, A.W.; Dal Grande, E.; de Courten, B.; Baye, E.; Gonzalez-Chica, D.; Hyppönen, E.; Shi, Z.; et al. Burden and trend of diet-related non-communicable diseases in Australia and comparison with 34 OECD countries, 1990–2015: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fardet, A.; Boirie, Y. Associations between food and beverage groups and major diet-related chronic diseases: An exhaustive review of pooled/meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 741–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contento, I. Nutrition Education, 3rd ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Contento, I.R. Nutrition Education: Linking Research, Theory and Practice; Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC: Sudbury, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, J.A.; Tischler, V. Qualitative research in nutrition and dietetics: Getting started in qualitative research. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bai, S.; Chen, J.; Gao, R.; Guo, Q.; Wang, P. Fundamental Knowlege for Health Managemen (健康管理师基础知识); People’s Medical Publishing House (CN): Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Information Office of the State Council (China). Report of Chronic Disease in Chinese Residents 2020. Available online: http://www.scio.gov.cn/xwfbh/xwbfbh/wqfbh/42311/44583/wz44585/Document/1695276/1695276.htm (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Hu, S.; Gao, R.; Liu, L.; Zhu, M.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Gu, D.; Yang, Y.; et al. Summary of the 2018 Report of Cardiovascular Disease in China (中国心血管病报告2018摘要). Chin. Circ. J. 2019, 34, 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, W. Diet, Nutrition and Chronic Disease in Mainland China. J. Food Drug Anal. 2012, 20, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.-Q.; Li, F.; Dong, R.-H.; Chen, J.-S.; He, G.-S.; Li, S.-G.; Chen, B. The development of a chinese healthy eating index and its application in the general population. Nutrients 2017, 9, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Gullick, J.; Neubeck, L.; Koo, F.; Ding, D. Acculturation is associated with higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk-factors among Chinese immigrants in Australia: Evidence from a large population-based cohort. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 2017, 24, 2000–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajpathak, S.N.; Wylie-Rosett, J. High Prevalence of Diabetes and Impaired Fasting Glucose Among Chinese Immigrants in New York City. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2011, 13, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Zhao, D. Cardiovascular diseases and risk factors among Chinese immigrants. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2016, 11, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.; Wright, D.J.; Fang, C.Y. Acculturation and Dietary Change Among Chinese Immigrant Women in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshner, L.; Yi, S.S.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Matthan, N.R.; Beasley, J.M. Acculturation and Diet Among Chinese American Immigrants in New York City. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzz124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenmöller, D.L.; Gasevic, D.; Seidell, J.; Lear, S.A. Determinants of changes in dietary patterns among Chinese immigrants: A cross-sectional analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G. Food, eating behavior, and culture in Chinese society. J. Ethn. Foods 2015, 2, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Z.C. Principles of diet therapy in ancient Chinese medicine: ‘Huang Di Nei Jing’. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993, 2, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research. 2017. Available online: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Qualitative_Research2017_0.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Hannes, K.; Lockwood, C.; Pearson, A. A comparative analysis of three online appraisal instruments’ ability to assess validity in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2010, 20, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. 2006. Available online: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancasteruniversity/contentassets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Veeck, A.; Burns, A.C. Changing tastes: The adoption of new food choices in post-reform China. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badanta, B.; de Diego-Cordero, R.; Tarriño-Concejero, L.; Vega-Escaño, J.; González-Cano-Caballero, M.; García-Carpintero-Muñoz, M.Á.; Lucchetti, G.; Barrientos-Trigo, S. Food Patterns among Chinese Immigrants Living in the South of Spain. Nutrients 2021, 13, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.; Lee, J.; Ristovski-Slijepcevic, S. Perceptions of food and eating among Chinese patients with cancer: Findings of an ethnographic study. Cancer Nurs. 2009, 32, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Nathan, A.; Choi, W.K.; Ngan, W.; Yin, S.; Thornton, L.; Barnett, A. Built and social environmental factors influencing healthy behaviours in older Chinese immigrants to Australia: A qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G.G.; Kagawa-Singer, M.; Foerster, S.B.; Lee, H.; Pham Kim, L.; Nguyen, T.U.; Fernandez-Ami, A.; Quinn, V.; Bal, D.G. Seizing the moment: California’s opportunity to prevent nutrition-related health disparities in low-income Asian American population. Cancer 2005, 104 (Suppl. 12), 2962–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Higginbottom, G.M.A.; Vallianatos, H.; Shankar, J.; Safipour, J.; Davey, C. Immigrant women’s food choices in pregnancy: Perspectives from women of Chinese origin in Canada. Ethn. Health. 2018, 23, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.R.; Wu, Y.; Jing, L.M.; Jaacks, L.M. Enablers and barriers to improving worksite canteen nutrition in Pudong, China: A mixed-methods formative research study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.D. Yang sheng, care and changing family relations in China: About a ‘left-behind’ mother’s diet. Fam. Relatsh. Soc. 2020, 9, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, D.; Bauer, K.D. Exploratory investigation of obesity risk and prevention in Chinese Americans. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2007, 39, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Chen, K. Analysing the reasons of university students’ choice of eating locations (影响大学生选择饮食消费场所的原因分析——以安徽财经大学为例). Mark. World. 2019, 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.; Liu, Y.; Gaither, S.; Marsan, S.; Zucker, N. The clash of culture and cuisine: A qualitative exploration of cultural tensions and attitudes toward food and body in Chinese young adult women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 54, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, N.; Brown, J.L. Chinese American Family Food Systems: Impact of Western Influences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Chi, I. Acculturation and health behaviors among older Chinese immigrants in the United States: A qualitative descriptive study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, B.; Hong-Bo, L.; Chen, T. Innovations in the agro-food system. Br. Food, J. 2016, 118, 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, B.; Ashman, H.; Dunshea, F.R.; Hutchings, S.; Ha, M.; Warner, R.D. Exploring Meal and Snacking Behaviour of Older Adults in Australia and China. Foods 2020, 9, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.; Chapman, G.E.; Levy-Milne, R.; Balneaves, L.G. Exploring the dietary choices of Chinese women living with breast cancer in Vancouver, Canada. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 1675–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, S.A.; Seymour, J.E.; Chapman, A.; Holloway, M. Older Chinese people’s views on food: Implications for supportive cancer care. Ethn. Health 2008, 13, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, K.; Chan, F.; Prichard, I.; Coveney, J.; Ward, P.; Wilson, C. Intergenerational transmission of dietary behaviours: A qualitative study of Anglo-Australian, Chinese-Australian and Italian-Australian three-generation families. Appetite 2016, 103, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satia, J.A.; Patterson, R.E.; Taylor, V.M.; Cheney, C.L.; Shiu-Thornton, S.; Chitnarong, K.; Kristal, A.R. Use of qualitative methods to study diet, acculturation, and health in Chinese-American women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2000, 100, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, S.; Sharkey, J.R.; Mathews, A.E.; Laditka, J.N.; Laditka, S.B.; Logsdon, R.G.; Sahyoun, N.; Robare, J.F.; Liu, R. Perceptions and beliefs about the role of physical activity and nutrition on brain health in older adults. Gerontologist 2009, 49 (Suppl. 1), S61–S71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.W.; Smith, C. Acculturation and environmental factors influencing dietary behaviors and body mass index of Chinese students in the United States. Appetite 2016, 103, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Barker, J.C. Hot tea and juk: The institutional meaning of food for Chinese elders in an American nursing home. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2008, 34, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Z.; Yue, Z.J.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Ma, S.T.; Zhang, Z.K. Using social media to explore regional cuisine preferences in China. Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 43, 1098–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, P. Facilitators and Barriers to Healthy Eating in Aged Chinese Canadians with Hypertension: A Qualitative Exploration. Nutrients 2019, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.Q.; Zhang, C.Z. Detecting Users’ Dietary Preferences and Their Evolutions via Chinese Social Media. J. Database Manag. 2018, 29, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Jin, Q.; Zhao, Y.-Y.; Liang, T.-T.; Qian, S.-Y.; Du, Y.-R.; Wang, R.Y.; Liu, Q. Analysis of Chinese citizens’ traditional Chinese medicine health culture literacy level and its influence factors in 2017. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2019, 44, 2865–2870. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, A.; Huang, H.; Kong, F. Relationship between food composition and its cold/hot properties: A statistical study. J. Agric. Food Res. 2020, 2, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Mu, S.; Tan, T.; Yeung, A.; Gu, D.; Feng, Q. Belief in and use of traditional chinese medicine in shanghai older adults: A crosssectional study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xutian, S.; Tai, S.; Yuan, C.-S.; World, S. Handbook of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Singapore; World Scientific Pub. Company: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, V.; Wong, E.; Woo, J.; Lo, S.V.; Griffiths, S. Use of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2007, 13, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongjie, Y.; Tong, X.; Wang, H.; Tian, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Traditional Chinese Medicine for Diabetes: A Double-Blind, Randomised, Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56703. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Meng, F.; Wang, D.; Guo, Q.; Ji, Z.; Yang, L.; Ogihara, A. Perceptions of traditional Chinese medicine for chronic disease care and prevention: A cross-sectional study of Chinese hospital-based health care professionals. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Mao, J.J.; Vertosick, E.; Seluzicki, C.; Yang, Y. Evaluating Cancer Patients’ Expectations and Barriers Toward Traditional Chinese Medicine Utilization in China: A Patient-Support Group–Based Cross-Sectional Survey. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Hsieh, E. The Social Meanings of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Elderly Chinese Immigrants’ Health Practice in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor Health 2012, 14, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.S. Traditional Chinese Medicine in the United States. In Search of Spiritual Meaning and Ultimate Health; Lexington Books: Franklin County, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Philipp, A.D.M.; Ho, E. (Eds.) Migration, Home and Belonging: South African Migrant Women in Hamilton, New Zealand. N. Z. Popul. Rev. 2010, 36, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kouris-Blazos, A. Morbidity mortality paradox of 1st generation Greek Australians. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 11 (Suppl. 3), S569–S575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, R.C.M.; Yu, S.W.K. Culturally sensitive approaches to health and social care: Uniformity and diversity in the Chinese community in the UK. Int. Soc. Work. 2009, 52, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tan, X.; Shi, H.; Xia, D. Nutrition and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM): A system’s theoretical perspective. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy: 2014–2023. 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506096 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Kastner, J. Chinese Nutrition Therapy: Dietetics in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM); Thieme Medical Publishers, Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bertschinger, R. Huangdi Neijing. In Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures; Selin, H., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 2205–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A. A Field Guide to the Huángdì Nèijing Sùwèn: A Clinical Untroduction to the Yellow Emperor’s Internal Classic, Plain Questions; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK; ProQuest: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, D.A.; Markowitz, L.B.; Smith, S.E.; Rajack-Talley, T.A.; D’Silva, M.U.; Della, L.J.; Best, L.E.; Carthan, Q. Healthicization and Lay Knowledge About Eating Practices in Two African American Communities. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1961–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Shim, J.-M. Listen to Doctors, Friends, or Both? Embedded They Produce Thick Knowledge and Promote Health. J Health Commun. 2019, 24, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, J. Expert and lay knowledge: A sociological perspective. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 67, 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. Confucianism: A Modern Interpretation, 2012th ed.; Li, D., World, S., Eds.; World Scientific Pub. Company: Singapore; Zhejiang University Press: Hangzhou, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, P.; Lamb, K.V.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Feng, X.; Wu, Y. Identification of Family Factors That Affect Self-Management Behaviors Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Qualitative Descriptive Study in Chinese Communities. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019, 30, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.-H.; Shao, J.-H. ‘Have you had your bowl of rice?’: A qualitative study of eating patterns in older Taiwanese adults. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L.S.; Norhasmah, S.; Gan, W.Y.; Nur’Asyura, A.S.; Nasir, M.T.M. The Identification of the Factors Related to Household Food Insecurity among Indigenous People (Orang Asli) in Peninsular Malaysia under Traditional Food Systems. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fang, L. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Food Safety Attributes in China: A Meta-Analysis. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2021, 33, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Jackson, P.; Wang, W. Consumer anxieties about food grain safety in China. Food Control 2017, 73, 1256–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Snell, H.A.; Ma, H. Food safety concerns and consumer preferences for food safety attributes: Evidence from China. Food Control 2020, 112, 107157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caeolyn Boyce, P.N. A Guide for Designing and Conducting In-Depth Interviews for Evaluation Input. 2006. Available online: https://donate.pathfinder.org/site/DocServer/m_e_tool_series_indepth_interviews.pdf;jsessionid=00000000.app274b?NONCE_TOKEN=BA697594778DDEA9A3239E75128718D9 (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Shepherd, R.; Raats, M.; Nutrition, S.; International, C.A.B. The Psychology of Food Choice; CABI Pub.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.W. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition); 2018. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/phenomenology/ (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Majid, U.; Vanstone, M. Appraising Qualitative Research for Evidence Syntheses: A Compendium of Quality Appraisal Tools. Qual. Health Res. 2018, 28, 2115–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Title | First Author (Year of Publication) | Location | Sampling Approach | Data Collection Methods | Participant Characteristics | Summarised Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changing Tastes: The Adoption of New Food Choices in Post-reform China [24] | Ann Veeck, A. (2003) | Nanjing, China | Purposive sampling | Structured observations; interviews with food shoppers and food retailers; focus groups with food shoppers. Field notes, photographs, information from the popular media in Nanjing. | Primary food shoppers (n = 20). Individuals (employees or entrepreneurs) who work in the food retail industry of Nanjing (n = 20). Three focus groups with people from different age groups: 25–35 y (n = 11), 34–35 y (n = 8), 46 y and older (n = 5). | There was an interplay of factors affecting Chinese consumers’ food choices. Increased income and time constraints lead to more processed food consumption. Participants also wanted to hold onto their traditional food consumption patterns, such as an emphasis on freshness, and cooking food to please family members. |

| Food Patterns Among Chinese Immigrants Living in the South of Spain [25] | Badanta, B. (2021) | Andalusia, Spain | Purposive sampling, snowball sampling | Face to face semi-structured interviews (15–30 min), field notes. | Chinese immigrants (n = 133), 61.7% F, 38.3% M, age range:18–55 y, average age: 30.7 y, living in Spain for average 11 y. Majority were ethnic Han, 78.3% from Zhejiang. 71% had medium-low educational levels. | Participants preferred a Chinese diet, but also integrated some Western foods. The concept of TCM and Chinese dietary norms influenced their food choices. The availability of Chinese food was not a problem in Spain, but long working hours limited their ability to eat healthily. Females and young participants were more concerned with healthy eating. |

| Perceptions of Food and Eating Among Chinese Patients with Cancer: Findings of an Ethnographic Study [26] | Bell, K. (2009) | City unspecified, Canada | Implied convenience sampling | Observations, key informant interviews. | Observations: Cantonese-speaking participants (n = 96), 36% M, 64% F, 61% cancer patients, 39% family members. Informant interviews: n = 7. | For the cancer patients, eating difficulties were often mentioned and were major concerns. They believed that the ability to eat well was very important for their health. The conflicts between Chinese and Western dietary recommendations confused the participants. |

| Built and Social Environmental Factors Influencing Healthy Behaviours in Older Chinese Immigrants to Australia: A Qualitative Study [27] | Cerlin, E. (2019) | Melbourne, Australia | Purposive convenience sampling | Nominal group technique sessions (n = 12), four sessions were designed for healthy diet | Participants (n = 91), 9 M, 18 F, age range: 60–85 y, average age: 71 y, living in Australia from 1–58 y (average 12 y); Most lived with their adult children. | There were 25 facilitators and 25 barriers for healthy diet identified. Facilitators: high food safety standards/regulations, receiving health education, family member support, educational information through Chinese newspapers or community talks, availability of healthy foods in grocery stores. Barriers: lack of family/household member’s support, financial restrictions, unhealthy food market environment. Wants: better provision of educational information, better access to grocery stores and fresh produce, improved public transport, fewer junk food outlets. |

| Seizing the moment: California’s opportunity to Prevent Nutrition-related Health Disparities in Low-income Asian American Population [28] | Harrison, G.G. (2005) | California, USA | Implied convenience sampling and purposive sampling | Focus groups (n = 24), and key informant interviews (n = 15) | Participants (n = 236):15 key informants, 116 adults (all parents), and 105 youths involved in focus groups. The adult participants were all low-income, first-generation immigrants. | Health beliefs (eating fresh fruit and vegetables, physical activity) were positive factors promoting healthier food choices. However, children’s adoption of American eating habits, the lure of fast food, and long work hours were barriers to following a healthy dietary pattern. Moreover, the trust in TCM concepts affected food choices. |

| Immigrant Women’s Food Choices in Pregnancy: Perspectives from Women of Chinese Origin in Canada [29] | Higginbottom, G.M.A. (2018) | Alberta, Canada | Purposive sampling | Women participated in one semi-structured interview, followed by a second photo-assisted, semi-structured interview which incorporated photographs taken by the women themselves. | Women (n = 23) who were in the perinatal period (from 5 months before to 1 month after childbirth), relocated from China to Canada within the past 10 years, age range: 26–42 y, average 31.6 y, highly educated, all had completed some form of post-secondary education. | The food and health related behaviours of immigrant females were influenced by their lay knowledge about health, cultural knowledge concerning antenatal and postnatal foods, TCM beliefs, social advice, health/nutrition information, and socioeconomic factors. |

| Enablers and Barriers to Improving Worksite Canteen Nutrition in Pudong, China: A Mixed Methods Formative Research Study [30] | Li, R. (2018) | Shanghai, China | Implied purposing sampling | In-depth interviews (n = 5), focus groups (n = 6), field observations | Community health centre administrators (n = 3) and canteen managers and staff (n = 3). Focus group participants: 19 M and 36 F employees, age 25–67 y. Male participants had a higher BMI than females. | Participants were proud of Chinese foods and cooks. They struggled with the balance between taste and nutrition. They felt that tasty foods were often unhealthy. Food safety concerns influenced participants eating behaviour (e.g., only eating in worksite canteen or bringing food to work). |

| Yang sheng, Care and Changing Family Relations in China: about a “Left-behind” Mother’s Diet [31] | Lin, X. (2020) | Mother in China, son (author) in the UK | Implied purposive sampling | Written communication between mother and son via WeChat | A Chinese migrant adult son (the author) living in the UK and his retired mother (in China) | Food practice intertwined with social and historical transformations. Yang sheng represented not only self-responsibility for health, but it also illustrated how intergenerational families show care and love for each other. (The author’s mother ate less to maintain her health, so that she would not be a burden on her son as she got older.) |

| Exploratory investigation of obesity risk and prevention in Chinese Americans [32] | Liou, D. (2007) | New York City, USA | Purposive sampling | In-depth interviews | Healthy US-born Chinese American adults (n = 40), 24 F, 16 M, age range 18–30 y, mean age 22 y, 60% full-time college students, 40% full-time employees. | Social environmental factors promoted unhealthy food choices (overeating) in Chinese Americans, including advertisements, inexpensive, and convenient fast food. They believed the traditional Chinese diet was healthier, but the degree of acculturation to the host country resulted in eating less Chinese food. Some traditional Chinese beliefs encouraged a slightly heavier physique. |

| 影响大学生选择饮食消费场所的原因分析(Analysing the reasons of university students’ choice of eating location) [33] | Liu, W. (刘威) (2019) | Anhui, China | Implied convenience sampling | First, university students (n = 485) filled out the questionnaire. Second, researchers interviewed some students regarding the reasons for their daily food choices. | The number of students being interviewed was not identified. The students were undergraduates and studying either science or liberal art subjects at Anhui university. 40% F, 60% M. | Food safety and hygiene, time restrictions, cost, food taste, cuisine variety, and convenience of online shopping were factors influencing the undergraduate students’ choice of eating location. |

| The Clash of Culture and Cuisine: A qualitative Exploration of Cultural Tensions and Attitudes Toward Food and Body in Chinese Young Adult Women [34] | Liu, Y. (2020) | China online | Implied convenience sampling | Semi-structured interviews, via email (n = 27; 23 in English, 4 in Chinese) or Skype (n = 7, all in Chinese) | Adult women (n = 34), age range: 18–22 y, all had parents of Chinese descent, all were either currently living in mainland China or Hong Kong or had lived there for most of their lives (>10 y). | Participants encountered cultural eating norms (parents or grandparent pushing them to eat, obeying means a good child) and feminine appearance norms (being thin to achieve social acceptance). They developed different strategies to address these conflicts, either by fighting against the norms, accepting or ignoring the norms. |

| Chinese American Family Food Systems: Impact of Western Influences [35] | Lv, N. (2010) | Pennsylvania, USA | Convenience sampling | In-depth interviews (90 min). Couples were interviewed together first, then each partner individually. | Twenty couples (n = 40 individuals) with at least 1 child aged 5 y or older enrolled in a Chinese school in 1–3 sites in Pennsylvania. Age range: 21–65 y. Mostly dual-income, well-educated, middle-aged parents. | Chinese parents liked Chinese food, whereas children preferred Western food. When children got older, they started to appreciate Chinese foods. Fathers dominated the food choices of the family. Families had certain rules about food and used different strategies to balance everyone’s preferences, but often struggled to keep rules consistent. Many Chinese families’ diets were mainly Chinese style (Western breakfast, Chinese lunch and dinner). |

| Acculturation and Health behaviours among older Chinese immigrants in the United States: A Qualitative Descriptive Study [36] | Mao, W. (2019) | Los Angeles, USA | Purposive sampling | Face-to-face semi-structured interviews | Participant (n = 24), average age: 77 y, living in US for 22 y; 54.2% F, 45.8% M; participants were from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. 70.8% spoke English, 54.2% spoke Cantonese at home. 54.2% reported good health | Older Chinese immigrants had limited interactions with other cultural groups. They depended on Chinese behaviour patterns and intra-ethnic networks. They exhibited strong maintenance of Chinese culture with some American cultural learning. Participants showed a strong identification with Chinese ethnicity contentment, fatalism, collectivism, individualism, and independence. Most followed traditional Chinese eating patterns or behaviours. |

| Innovations in the Agro-food System: Adoption of Certified Organic Food and Green Food by Chinese Consumers [37] | McCarthy, B. (2016) | Unspecified City, China | Convenience sampling | Structured questionnaire: open-ended survey questions designed to gather qualitative data | Respondents (n = 58), primarily F, age range: 35–44 y, living in tier 2 and 3 Chinese cities, married and with children. None were university educated, income 5000–8000 RMB/month. | Health and safety, rather than environmental considerations, were important determinants when making organic food purchasing decisions. Participants used a variety of strategies to deal with food related risks: buying food directly from farmers, purchasing overseas products, purchasing from formal channels. Information resources used: the Internet first, followed by friends and advertisements. |

| Exploring Meal and Snacking Behaviour of Older Adults in Australia and China [38] | Mena, B. (2020) | Frankston, Victoria, Australia | Implied convenience sampling | Three-stage focus groups: Stage 1: interview about meal and snacking behaviour, Stage 2: meat product tasting, Stage 3: perceptual mapping. Total length: 2 h. | Australians (n = 16) 13 F, 3 M, age range: 65–79 y; Chinese Australians (n = 21) 17 F, 4 M, age range: 60–81 y. All were meat eaters. They self-reported having good health, were physically active, and did not take any medication. | Australian participants did not eat breakfast and dinner regularly but snacked throughout the day. However, Chinese participants ate three meals regularly, and snacked only occasionally. Texture and flavour were key drivers of food choice for both groups. |

| Exploring the Dietary Choices of Chinese Women Living with Breast Cancer in Vancouver, Canada [39] | Ng, B. (2020) | Vancouver, Canada | Purposive sampling | Semi-structured interviews (60 min). Follow-up focus group with six participants | Chinese Canadian women (n = 19), age range: 41–73 y, diagnosed with breast cancer within the last 5 years. They were first or second-generation immigrants. Fifteen were married, most had children. | Breast cancer diagnosis resulted in dietary changes in participants: avoiding or restricting the consumption of certain foods, using TCM and natural health products.Obstacles to desired dietary change: the interplay between family life, personal food and social life, and work; the high cost and lack of availability of specialty foods, difficulties in assessing reliable and accurate nutrition information. Facilitators: support from family members. |

| Older Chinese People’s Views on Food: Implications for Supportive Cancer Care [40] | Payne, S.A. (2008) | Sheffield and Manchester, UK | Implied convenience sampling | Focus groups (n = 7), face to face semi-structured interview (40–50 min) | Stage 1: Participants (n = 46) were divided into 7 focus groups, Stage 2: Participants (n = 46) were involved in in-depth interviews. Older people were ≥ 50 y. Mean age: 66.25 y, 26 M, 66 F. Geographical origin: Mainland China (n = 49), Hong Kong (n = 41), majority self-reported poor health condition, 85% spoke Cantonese. | The older Chinese immigrants’ food beliefs: Food can be therapeutic, supportive, comforting, and prevent illness. Certain foods and cooking methods can be risky to health. These beliefs influenced their attitude toward the hospital food. They thought that foods in hospital were not culturally appropriate. Understanding the perceived cultural and therapeutic significance of food in hospital was important. |

| Intergenerational Transmission of Dietary Behaviours: A Qualitative Study of Anglo-Australian, Chinese-Australian and Italian-Australian Three-generation Families [41] | Rhodes, K. (2016) | City unspecified, Australia | Purposive sampling | Semi-structured interviews (40–60 min) | Three-generation families (n = 27), with ethnic backgrounds: Anglo-Australian (n = 11), Chinese-Australian (n = 8), Italian-Australian (n = 8). Average group interview size = 4, including at least one child (7–18 y), one parent, and one grandparent. Families were from middle class backgrounds. F 63.2%, M 36.8% | All families: Mothers and grandmothers dominated family food choice decisions, they influenced fruit and vegetable consumption by controlling purchasing decisions, insisting on consumption, reminding, and monitoring certain foods. In Chinese families: traditional culture played a large role in adult member’s food decisions. They believed the cultural diet was beneficial for health and wellbeing. The concept of TCM also influenced their food choice. |

| Use of Qualitative Methods to Study Diet, Acculturation, and Health in Chinese American Women [42] | Satia, J.A. (2000) | Seattle, USA | Implied purposive sampling | Observation of participants in their home kitchens, semi-structured in-person interviews (90 min), focus groups (2 focus groups, 2 h long each, 6 people each), 24-h dietary recalls | Interviews: 30 women, average age 51.9 y, 83.3% married, 67% had high school or lower education, 70% spoke little/no English, time spent living in the US: median 6 y. Focus groups: 12 women, average age 64.5 y, first generation Chinese Americans, 83% had low English proficiency, time living in the US: median 7 y. | Factors influencing food choice: Predisposing factors-traditional beliefs, taste preferences, beliefs about healthy eating, religion, existing dietary knowledge. Reinforcing factors-attitudes of friends, family members and health care providers. Enabling factors-convenience, cost, availability, quality/freshness. |

| Perceptions and Beliefs About the Role of Physical Activity and Nutrition on Brain Health in Older Adults [43] | Wilcox, S. (2009) | City unspecified, USA | Purposive snowball sampling | Focus groups (n = 42), of which, four focus groups included Chinese immigrant participants | Community-dwelling ethnically diverse older adults (n = 396), of which n = 36 were Chinese participants. 30.6% M, 69.4% F, age range: 50–90 y, 55.6% healthy weight, 38.9% overweight. | Chinese participants were more likely than Caucasians to be regularly physically active, eat fish at least once weekly, and to be within the healthy weight range. They believed that diet and physical activity help keep the brain healthy. Participants reported that portion control and healthy food preparation methods were important for brain health. They agreed that some types of foods should be eaten, and others avoided. |

| Acculturation and Environmental Factors Influencing Dietary Behaviours and Body Mass Index of Chinese Students in the United States [44] | Wu, B. (2016) | Chicago, USA | Implied convenience sampling | Focus groups (n = 7), each involving 4–7 participants, 24-h dietary recalls, food adoption scores, degree of acculturation, height and weight measures | Chinese students (n = 43) born and raised in mainland China, average length of stay in the USA: 20.3 months, 16 M, 27 F, age range: 19–31 y, 53% undergraduate, 47% graduate; Most lived in rented apartments. 19% M and 7% F were overweight/obese. | Extent of acculturation can predict Chinese students’ American food consumption. Having more American friends led to more exposure to American food. Living and cooking situation, and busy lifestyle were major factors influencing Chinese students’ food intake. Chinese students had difficulties in accepting raw, sweet, cold, or large portion sized American foods. |

| Hot Tea and Juk: The Institutional Meaning of Food for Chinese Elders in an American Nursing Home [45] | Wu, S. (2008) | City unspecified, USA | Implied purposive sampling | Meal observations, semi-structured interviews with residents (n = 7), family members (n = 9), and staff members (n = 17). Field notes. | Nursing home residents (n = 7), most were women, average age 81 y, all were immigrants, with the majority from Southern China, time living in the US: average 25 y. None spoke English fluently. Staff participants (n = 17): twelve were women, 5 men. | The American nursing home emphasised therapeutic personalised diets for the Chinese elders. They tried to provide Chinese food but lacked consideration of authentic Chinese ingredients and traditional presentation style, so failed to provide a meaningful Asian culturally appropriate diet. The Chinese elders prioritised community harmony over personal needs by either accepting the food provided or requiring family members to bring Chinese food to the nursing home. |

| Using social media to Explore Regional Cuisine Preferences in China [46] | Zhang, C. (2019) | China, online, Sina Weibo | Document analysis | Dish names (identified from Meishijie, a social media platform) were used as queries to retrieve related microblogs (food reviews) in Sina Weibo | There were 5156 cuisine names identified from 20 categories that represent Chinese regional cuisines. 3,209,990 cuisine reviews (personal microblogs) were retrieved. | Sichuan cuisine was most favoured among Sina Weibo users, followed by Shandong, Shanghai, Beijing, and Cantonese cuisine. The high-frequency dishes had lower regional differences among users. Geographical proximity was the key factor determining the similarity of regional dish preferences. |

| Facilitators and Barriers to Healthy Eating in Aged Chinese Canadians with Hypertension: A Qualitative Exploration [47] | Zhou, P. (2018) | Unspecified City, Canada | Implied convenience sampling | Telephone interviews (30–45 min), asking two open ended questions | Chinese Canadians (n = 30) with stage one hypertension; Mean age 60.8 y; living in Canada average length: 9.7 y, 16 F, 14 M, 66.7% participants lived a southern Chinese lifestyle. | There were facilitators and barriers at personal, family, community, and social levels that influenced healthy eating. Factors promoting healthy eating: experiencing positive effects of healthy diet, small family, supportive family, community health education workshops, printed educational materials. Factors impeding healthy eating: difficulty changing traditions, prioritising children’s wants, busy lifestyle. |

| Detecting Users’ Dietary Preferences and Their Evolutions via Chinese social media. [48] | Zhou, Q. (2018) | China online, Sina Weibo | Document analysis | 25,675 dish names were used as queries to retrieve related microblogs. (Food reviews) in Sina Weibo | 3,975,800 microblogs from 34 regions of China, reviews written by males (n = 1,207,909), females (n = 2,767,891), search date May 2015. | 1. Popular dishes had fewer regional differences, while unpopular dishes had apparent regional restrictions. 2. Chinese users were most satisfied with taste, dish appearance, and service, the most unsatisfying aspect was function (effect on health). 3. Diners valued dining atmosphere more than taste. 4. Dining atmosphere and food appearance were important aspects for diners. |

| First Author (Year) [ref.] | 1. Is There Congruity between the Stated Philosophical Perspective and the Research Methodology? | 2. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Research Question or Objectives? | 3. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Methods Used to Collect Data? | 4. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Representation and Analysis of Data? | 5. Is There Congruity between the Research Methodology and the Interpretation of Results? | 6. Is There a Statement Locating the Researcher Culturally or Theoretically? | 7. Is the Influence of the Researcher on the Research, and Vice- Versa, Addressed? | 8. Are Participants, and Their Voices, Adequately Represented? | 9. Is the Research Ethical According to Current Criteria or, for Recent Studies, and Is There Evidence of Ethical Approval by an Appropriate Body? | 10. Do the Conclusions Drawn in the Research Report Flow from the Analysis, or Interpretation, of the Data? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ann Veeck, A. (2003) [24] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Badanta, B. (2021) [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Bell, K. (2009) [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Cerlin, E. (2019) [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | Y | Y |

| Harrison, G.G. (2005) [28] | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | N | N | U | Y |

| Higginbottom, G.M.A. (2018) [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Li, R. (2018) [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Lin, X. (2020) [31] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | U | Y |

| Liou, D. (2007) [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Liu, W. (2019) [33] | Y | N | Y | U | U | N | N | U | U | Y |

| Liu, Y. (2020) [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Lv, N. (2010) [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Mao, W. (2019) [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| McCarthy, B. (2016) [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | U | Y |

| Mena, B. (2020) [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Ng, B. (2020) [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Payne, S.A. (2008) [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Rhodes, K. (2016) [41] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Satia, J.A. (2000) [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Wilcox, S. (2009) [43] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Wu, B. (2016) [44] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Wu, S. (2008) [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Zhang, C. (2019) [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | N | N | Y |

| Zhou, P. (2018) [47] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y |

| Zhou, Q. (2018) [48] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | U | U | Y |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang-Chen, Y.; Kellow, N.J.; Choi, T.S.T. Exploring the Determinants of Food Choice in Chinese Mainlanders and Chinese Immigrants: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020346

Wang-Chen Y, Kellow NJ, Choi TST. Exploring the Determinants of Food Choice in Chinese Mainlanders and Chinese Immigrants: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(2):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020346

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang-Chen, Yixi, Nicole J. Kellow, and Tammie S. T. Choi. 2022. "Exploring the Determinants of Food Choice in Chinese Mainlanders and Chinese Immigrants: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 14, no. 2: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020346

APA StyleWang-Chen, Y., Kellow, N. J., & Choi, T. S. T. (2022). Exploring the Determinants of Food Choice in Chinese Mainlanders and Chinese Immigrants: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 14(2), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14020346