Polyphenol Intake in Pregnant Women on Gestational Diabetes Risk and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Identification of Relevant Studies

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

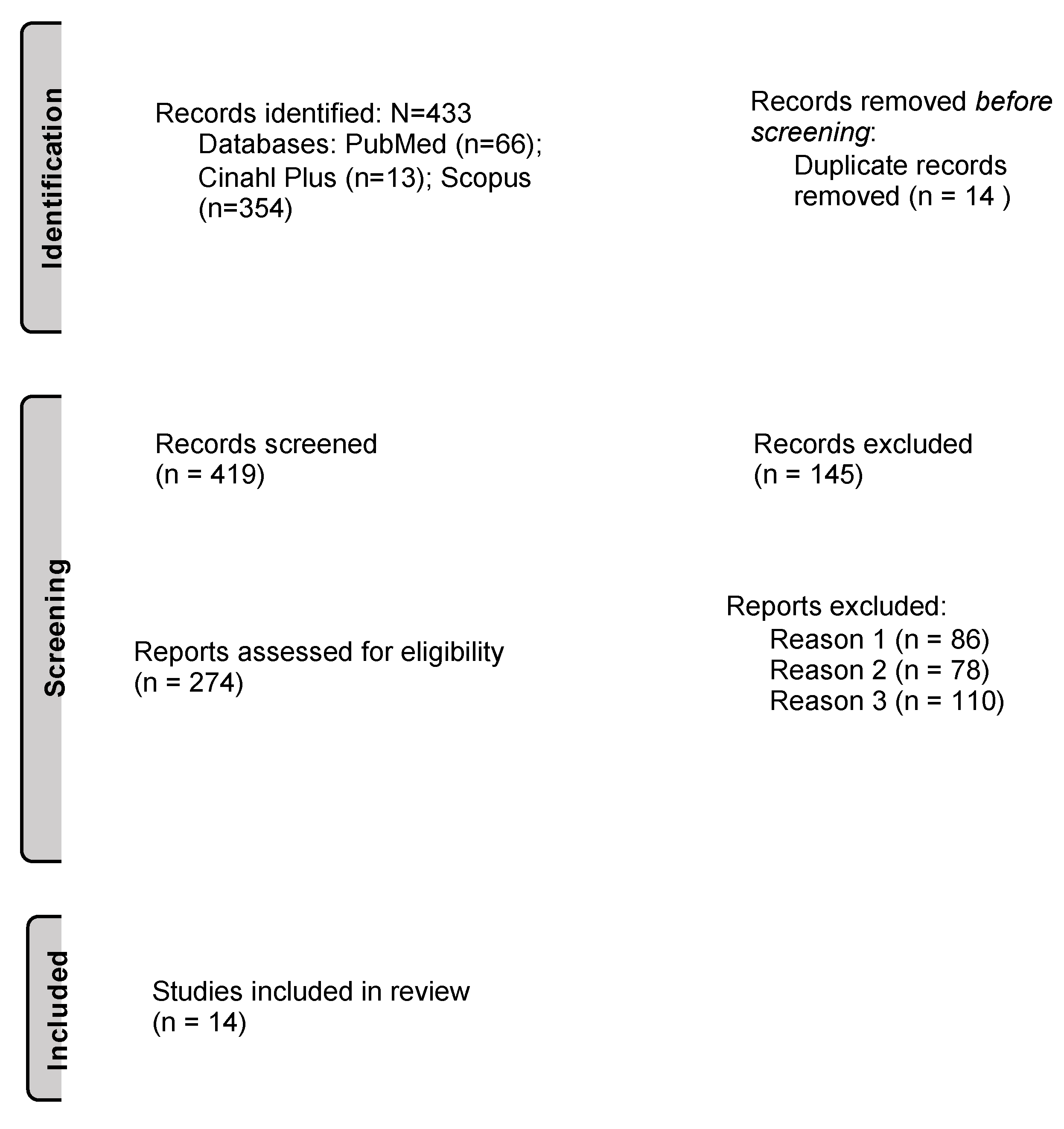

2.4. Selection of Relevant Studies

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pembrey, M.; Saffery, R.; Bygren, L.O. Human transgenerational responses to early-life experience: Potential impact on development, health and biomedical research. J. Med. Genet. 2014, 51, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio, E.; Jardí, C.; Bedmar, C.; Pallejà, M.; Basora, J.; Arija, V. Nutrient Intake during Pregnancy and Post-Partum: ECLIPSES Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajianfar, H.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Feizi, A.; Shahshahan, Z.; Azadbakht, L. The association between major dietary patterns and pregnancy-related complications. Arch. Iran Med. 2018, 21, 443–451. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, T.; Strömmer, S.; Vogel, C.; Harvey, N.C.; Cooper, C.; Inskip, H.; Woods-Townsend, K.; Baird, J.; Barker, M.; Lawrence, W.; et al. Improving pregnant women’s diet and physical activity behaviours: The emergent role of health identity. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purizaca Benites, M. La placenta y la barrera placentaria. Rev. Peru. De Ginecol. Y Obstet. 2015, 54, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.K.; Campbell, J.P. Placental structure, function and drug transfer. Contin. Educ. Anaes-Crit. Care Pain 2015, 15, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. How Will This Impact My Baby; American Diabetes Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, K.O.; Wang, C.C.; Chu, C.Y.; Chan, K.P.; Rogers, M.S.; Choy, K.W.; Pang, C.P. Pharmacokinetic studies of green tea cat-echins in maternal plasma and fetuses in rats. J. Pharm. Sci. 2006, 95, 1372–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.; Isaacs, J.; Krinke, U.B. Nutrición en las Diferentes Etapas de la Vida, 5th ed.; McGRAW-HILL Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil, P.; Olmedo, J. Gestational diabetes: Conceptos Actuales. Ginecol. Obstet. Mex. 2017, 85, 380–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kc, K.; Shakya, S.; Zhang, H. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Macrosomia: A Literature Review. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66 (Suppl. S2), 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, M.S.; Abdo, N.M.; Bettencourt-Silva, R.; Al-Rifai, R.H. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Europe: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence Studies. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 691033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez García, R.M.; Jiménez Ortega, A.I.; Peral-Suárez, Á.; Bermejo, L.M.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, E. Importancia de la nutrición durante el embarazo. Impacto en la composi-ción de la leche materna. Nutr. Hosp. 2020, 37, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Haddad, B.J.; Oler, E.; Armistead, B.; Elsayed, N.A.; Weinberger, D.R.; Bernier, R.; Burd, I.; Kapur, R.; Jacobsson, B.; Wang, C.; et al. Fetal origins of mental illness. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 221, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Healthy Diet [Internet]. WHO. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/behealthy/healthy-diet (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Canal Salut. Alimentació Saludable. [Internet]. Gencat. 2022. Available online: https://canalsalut.gencat.cat/ca/vida-saludable/alimentacio/saludable/ (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Ly, C.; Yockell-Lelièvre, J.; Ferraro, Z.M.; Arnason, J.T.; Ferrier, J.; Gruslin, A. The effects of dietary polyphenols on reproductive health and early development. Hum. Reprod. Update 2015, 21, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, 2, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiñones, M.; Miguel, M.; Aleixandre, A. Los polifenoles, compuestos de origen natural con efectos saludables sobre el sistema cardiovascular. Nutr. Hosp. 2012, 27, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zielinsky, P.; Piccoli, A.L.; Manica, J.L.; Nicoloso, L.H.; Vian, I.; Bender, L.; Pizzato, P.; Pizzato, M.; Swarowsky, F.; Barbisan, C.; et al. Reversal of fetal ductal constriction after maternal restriction of polyphenol-rich foods: An open clinical trial. J. Perinatol. 2011, 32, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, W. Dietary Polyphenols-Important Non-Nutrients in the Prevention of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases. A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ali, N.; Arrizabalaga, A.A. Los elementos de efectividad de los programas de educación nutricional infantil: La educación nutricional culinaria y sus beneficios. Rev. Española Nutr. Hum. Dietética 2015, 20, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alvarado-García, A.; Lamprea-Reyes, L.; Murcia-Tabares, K. La nutrición en el adulto mayor: Una oportunidad para el cuidado de enfermería. Enfermería Univ. 2017, 14, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno Hidalgo, C.M.; Lora López, P. Intervenciones enfermeras aplicadas a la nutrición. Nutr. Clin. Diet. Hosp. 2017, 37, 189–193. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ [Internet]. 29 March 2021. Available online: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71 (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Malvasi, A.; Kosmas, I.; Mynbaev, O.A.; Sparic, R.; Gustapane, S.; Guido, M.; Tinelli, A. Can trans resveratrol plus d-chiro-inositol and myo-inositol improve maternal metabolic profile in overweight pregnant patients? Clin. Ter. 2017, 168, e240-7. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A.; Crew, J.; Ebersole, J.L.; Kinney, J.W.; Salazar, A.M.; Planinic, P.; Alexander, J.M. Dietary blueberry and soluble fiber improve serum antioxidant and adipokine biomarkers and lipid peroxidation in pregnant women with obe-sity and at risk for gestational diabetes. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Zhong, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, R.; Xiong, T.; Hong, M.; Li, Q.; Kong, M.; Xiong, G.; Han, W.; et al. Inverse association of total polyphenols and flavo-noids intake and the intake from fruits with the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Su, S.; Yu, X.; Li, Y. Dietary epigallocatechin 3-gallate supplement improves maternal and neonatal treatment outcome of gestational diabetes mellitus: A double-blind randomised controlled trial. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krakowiak, P.; Walker, C.K.; Bremer, A.A.; Baker, A.S.; Ozonoff, S.; Hansen, R.L.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Maternal metabolic conditions and risk for autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e1121-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, Y.; Marks, D.J.; Grossman, B.; Yoon, M.; Loudon, H.; Stone, J.; Halperin, J.M. Exposure to gestational diabetes melli-tus and low socioeconomic status: Effects on neurocognitive development and risk of atten-tion-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zornoza-Moreno, M.; Fuentes-Hernández, S.; Prieto-Sánchez, M.T.; Blanco, J.E.; Pagán, A.; Rol, M.Á.; Parrilla, J.J.; Madrid, J.A.; Sánchez-Solis, M.; Larqué, E. Influence of gestational diabetes on circadian rhythms of children and their association with fetal adiposity. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2013, 29, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girchenko, P.; Tuovinen, S.; Lahti-Pulkkinen, M.; Lahti, J.; Savolainen, K.; Heinonen, K.; Pyhälä, R.; Reynolds, R.M.; Hämäläinen, E.; Villa, P.M.; et al. Maternal early preg-nancy obesity and related pregnancy and pre-pregnancy disorders: Associations with child developmental milestones in the prospective PREDO Study. Int. J. Obes. 2018, 42, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briana, D.D.; Papastavrou, M.; Boutsikou, M.; Marmarinos, A.; Gourgiotis, D.; Malamitsi-Puchner, A. Differential expression of cord blood neurotrophins in gestational diabetes: The impact of fetal growth abnormalities. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal. Med. 2018, 31, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Espinola, F.J.; Berglund, S.K.; Garcia, S.; Perez-Garcia, M.; Catena, A.; Rueda, R.; Sáez, J.A.; Campoy, C. Visual evoked poten-tials in offspring born to mothers with overweight, obesity and gestational diabetes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Norstedt, G.; Schalling, M.; Gissler, M.; Lavebratt, C. The risk of offspring psychiatric disorders in the setting of maternal obesity and diabetes. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panjwani, A.A.; Ji, Y.; Fahey, J.W.; Palmer, A.; Wang, G.; Hong, X.; Zuckerman, B.; Wang, X. Maternal Obesity/Diabetes, Plasma Branched-Chain Amino Acids, and Autism Spectrum Disorder Risk in Urban Low-Income Children: Evi-dence of Sex Difference. Autism Res. 2019, 12, 1562–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaltun, Ì.; Yapça, Ö.; Ayaydin, H.; Kara, T. An evaluation of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and specif-ic learning disorder in children born to diabetic gravidas: A case control study. Anadolu Psikiyatr. Derg. 2019, 20, 1–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.E.; Lee, S.S.; Mahrer, N.E.; Guardino, C.M.; Davis, E.P.; Shalowitz, M.U.; Ramey, S.L.; Dunkel Schetter, C. Prenatal maternal C-reactive protein prospectively predicts child executive functioning at ages 4–6 years. Dev. Psychobiol. 2020, 62, 1111–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arola-Arnal, A.; Oms-Oliu, G.; Crescenti, A.; del Bas, J.M.; Ras, M.R.; Arola, L.; Caimari, A. Distribution of grape seed fla-vanols and their metabolites in pregnant rats and their fetuses. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.M.; Do V van Lee, A.H. Polyphenol-rich foods and risk of gestational diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannasch, F.; Kröger, J.; Schulze, M.B. Dietary Patterns and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.A.; Keogh, J.B.; Clifton, P.M. Polyphenols and Glycemic Control. Nutrients 2016, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.; Sheedy, K. Effects of Polyphenols on Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, F.; Monteiro, R.; Calhau, C. Effect of polyphenols on the intestinal and placental transport of some bio-active compounds. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Castrejon, M.; Powell, T.L. Placental nutrient transport in gestational diabetic pregnancies. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrapal, M.; Khairnar, S.J.; Khan, J.; Dukhyil, A.B.; Ansari, M.A.; Alomary, M.N.; Alshabrmi, F.M.; Palai, S.; Deb, P.K.; Devi, R. Dietary Polyphenols and Their Role in Oxidative Stress-Induced Human Diseases: Insights Into Protective Effects, Antioxidant Poten-tials and Mechanism(s) of Action. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, G. The role of polyphenols in modern nutrition. Nutr. Bull. 2017, 42, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illsley, N.P.; Baumann, M.U. Human placental glucose transport in fetoplacental growth and metabolism. Bio-Chim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Mendonça, E.L.S.S.; Fragoso, M.B.T.; de Oliveira, J.M.; Xavier, J.A.; Goulart, M.O.F.; de Oliveira, A.C.M. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: The Crosslink among Inflammation, Nitroxidative Stress, Intestinal Microbiota and Al-ternative Therapies. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M.; Baierle, M.; Charão, M.F.; Bubols, G.B.; Gravina, F.S.; Zielinsky, P.; Arbo, M.D.; Cristina Garcia, S. Polyphenol-rich food general and on pregnancy effects: A review. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 40, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, J.; Wilson, C.A. The association between gestational diabetes and ASD and ADHD: A systematic re-view and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viada Pupo, E.; Gómez Robles, L. Estrés oxidativo. CCM 2017, 20, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Asmat, U.; Abad, K.; Ismail, K. Diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress-A concise review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, T.; Wu, X.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y. Oxidative stress and diabetes: Antioxidative strategies. Front. Med. 2020, 14, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirkovic, B.; Chagraoui, A.; Gerardin, P.; Cohen, D. Epigenetics and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: New Perspectives? Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccarello, D.; Sorrentino, U.; Brasson, V.; Marin, L.; Piccolo, C.; Capalbo, A.; Andrisani, A.; Cassina, M. Epigenetics of pregnancy: Look-ing beyond the DNA code. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 801–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ángeles, M.; Vázquez, S.; Palma, M.; Ubaldo, L.; Cervantes, G.; Rojas, A. Desarrollo de los ritmos biológicos en el recién nacido. Rev. Fac. Med. 2013, 56, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nankumbi, J.; Ngabirano, T.D.; Nalwadda, G. Knowledge, confidence and skills of midwives in maternal nutri-tion education during antenatal care. J. Glob. Health Rep. 2020, 4, e2020039. [Google Scholar]

- Arrish, J.; Yeatman, H.; Williamson, M. Midwives’ Role in Providing Nutrition Advice during Pregnancy: Meeting the Challenges? A Qualitative Study. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 7698510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomami, M.B.; Walker, R.; Kilpatrick, M.; Jersey S de Skouteris, H.; Moran, L.J. The role of midwives and obstet-rical nurses in the promotion of healthy lifestyle during pregnancy. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health 2021, 15, 263349412110318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián, R.E.; Peña, A.L.N.; Castell, E.C.; González-Sanz, J.D.D. Percepción de embarazadas y matronas acerca de los consejos nutricionales durante la gestación. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Moallem, S.A.; Afshar, M.; Etemad, L.; Razavi, B.M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Evaluation of teratogenic effects of crocin and safranal, active ingredients of saffron, in mice. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2016, 32, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study and Country | Year | Study Design | n | Pregnant Women Characteristic | Pregnancy Period | Study Groups and Period of Assessment | Polyphenol Dosage | Outcomes Measured | Main Findings on GDM Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malvasi et al. [26], Italy | 2017 | Prospective randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial | 110 | Pregnant and overweight women between 25 and 40 years old, first trimester’s gestational BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2. | Between 24th and 28th pregnancy week | Group 1: supplemented with trans-resveratrol in combination with myo-inositol and D-chiro-inositol. Group 2: only receives myo-inositol and D-chiro-inositol. Group 3: control group (placebo). Sixty days. | Group 1: 80 mg of trans-resveratrol, 200 mg of myo-inositol, 500 mg of D-chiro-inositol. Group 2: 138 mg of myo-inositol, 550 mg of D-chiro-inositol. | SBP, DBP, Total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides and blood-glucose level before and after the first 30 and 60 days of treatment. |

|

| Basu et al. [27], USA | 2021 | Randomized parallel arm study | 34 | Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), gestational age < 20 weeks with risk of GDM, singleton pregnancy, not having pregestational chronic diseases. | Between <20th and 32/36th pregnancy week | Group 1: under intervention with blueberries (two cups a day) and 12 g of soluble fiber. Group 2: under standard prenatal control. Eighteen weeks. | Two cups of l blueberries, 1600 mg of total polyphenols and 700 mg of anthocyanins. | Gain of gestational weight, blood-glucose levels and C-reactive protein in blood. Antioxidant biomarkers in maternal serum, adipokines in serum and hormonal biomarkers. Trace elements in plasma/blood? With a role in antioxidant/oxidative stress pathways (Se, Fe, Zn, Mg and Cu). |

|

| Gao et al. [28], China | 2021 | Prospective cohort study | 2231 | Pregnant women between 18 and 45 years old. | Between the 8th and 16th pregnancy week. | FFQ of 61 items, asking about the food frequency and portion during 4 weeks. Forty-one months. | An average of 319.9 mg of total polyphenols (201.6 mg from fruits) | Maternal clinical and sociodemographic data. Quartiles of diary polyphenols intake (Q1, <226.9 mg/d; Q2, 227–317.9 mg/d; Q3, 318–415.8 mg/d; and Q4, ≥415.9 mg/d), origin of the polyphenols (total polyphenols from fruits and vegetables). |

|

| Zhang et al. [29], China | 2017 | Double-blind randomized controlled trial | 404 | Pregnant women with singleton pregnancy, between 25 and 34 years old, with a diagnosis of GDM. | From the beginning of the third trimester to term | Group 1: instructed to consume one capsule of 500 mg of EGCG daily. Group 2: instructed to consume one capsule of 500 mg of starch powder as placebo. Three months. | 500 mg of ECGC | Maternal clinical and body weight data. Glucose and insulin metabolism: insulin, QUICKI, HOMA-IR and HOMA-β. Neonatal complications at birth: low birth weight, hypoglycemia, respiratory distress, macrosomia, 1 min APGAR, 5 min APGAR. |

|

| Study, Country | Publication Year | Study Design | n | Sample Characteristics | Data Taken into Consideration for the Analysis | Main Findings towards GDM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krakowiak et al. [30], USA. | 2012 | Population based, case-control study | 1004 | Children between 2 and 5 years old. Three groups: control, one with ASD and the other with DD. | Maternal clinical data including BMI, HBP, having any type of diabetes or taking any antidiabetic medication. Child’s gender and age, having any metabolic or neurologic disorder, control center. |

|

| Nomura et al. [31], USA. | 2012 | Ongoing cohort study | 212 | Children between 3 and 4 years old, with risk of developing ADHD who went to kindergarten in New York. English-speaking parents. Two groups: “in risk” (>6 symptoms according to their parents) and “typically developing” (<3 symptoms according to their parents). | Maternal, paternal and child clinical data, gender, ethnicity, low birth and socioeconomic status. Child neuropsychological functioning, temperament, and behavioral/emotional functioning in the follow-up (6 years old). |

|

| Zornoza-Moreno et al. [32], Spain | 2013 | Longitudinal prospective study | 63 | Pregnant women between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation, singleton pregnancy, age from 18 to 40 years old, non-smoking and not consuming docosahexaenoic acid supplements during pregnancy. Sample divided in 3 groups: control group, diagnosed with GDM and treated with diet and diagnosed with GDM treated with insulin. | Skin temperature, children activity and sleep time index at 15 days old, 1, 3 and 6 months old. Circadian-rhythm maturation. Gestational age, abdominal circumference at the beginning of the study and at birth, weight, length, BMI, waist/hip ratio at birth and at 3, 6 and 12 months old. |

|

| Girchenko et al. [33], Finland | 2018 | PREDO study: prospective pregnancy cohort study | 4785 | Singleton live-born children between 2006 and 2010 in hospitals of the Southern and Eastern Finland. | Maternal clinical data. Overweight, obesity, pregestational/gestational/ chronic HBP, GDM or Type 1 diabetes mellitus. |

|

| Briana et al. [34], Greece | 2018 | Cohort study | 60 | Pregnant women, in the third trimester of pregnancy, and their children. Different groups: 3 groups of mothers with GDM, one for large for gestational age, the second intrauterine-growth-restricted, and the third appropriate for gestational age. Group four also appropriate for gestational age, but without GDM (control). | Child: birthweight, gestational age, customized centile and gender. Mother: age, parity, delivery mode, GDM. Concentrations of: BDNF, NGF and NT-4. |

|

| Torres-Espínola et al. [35], Spain | 2018 | PREOBE study: prospective mother–child cohort study | 331 | Pregnant women with singleton pregnancies and age between 18 and 45 years old, between 12 to 20 weeks of pregnancy. Four groups: healthy weight, overweight, obesity and GDM. | Child: gestational age, gender, anthropometrics and cord-blood laboratory status. Maternal clinical data, marital status and intelligence quotient. Blood-glucose and iron levels. |

|

| Kong et al. [36], Finland | 2018 | Large prospective population-based cohort study | 649.043 | Pregnancies between 2004 and 2014 in Finland. Differentiation between non-diabetic mothers, mothers with pregestational diabetes and mothers with GDM. | Child: Offspring year of birth, gender, any perinatal problem, number of fetuses, mode of delivery (vaginal, instrumental, caesarean and others), Mother: Maternal age, parity, marital status, country of birth, smoking habit, psychiatric disorders, diagnoses of systemic inflammatory disorders and BMI. |

|

| Panjwani et al. [37], USA | 2019 | Prospective longitudinal and intergenerational cohort study | 789 couples (mother–child) | Pregnant women from 2004 to 2015, with metabolic measurements and children attended in Boston Medical Center without any development disorder. | Mother clinical data. Child: gender, gestational age and birth weight. Concentration of BCAA. |

|

| Akaltun et al. [38], Turkey | 2019 | Case–control study | 265 | Children born between 2005 and 2010 in Atatürk to diabetic and non-diabetic mothers in terms of ADHD and SLD. | Gender, age, having ADHD or SLD, mother’s age, child’s intelligence quotient and HbA1c. |

|

| Morgan et al. [39], USA. | 2020 | Prospective longitudinal study | 100 | Children between 4 and 6 years old. | Child data and birth or neonatal-health complications. Cognitive flexibility and response inhibition. Maternal clinical data, level of pro-inflammatory factors (HbA1c, C-reactive protein and blood pressure) in pre-pregnancy and in the second and third trimester. |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salinas-Roca, B.; Rubió-Piqué, L.; Montull-López, A. Polyphenol Intake in Pregnant Women on Gestational Diabetes Risk and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183753

Salinas-Roca B, Rubió-Piqué L, Montull-López A. Polyphenol Intake in Pregnant Women on Gestational Diabetes Risk and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(18):3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183753

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalinas-Roca, Blanca, Laura Rubió-Piqué, and Anna Montull-López. 2022. "Polyphenol Intake in Pregnant Women on Gestational Diabetes Risk and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 14, no. 18: 3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183753

APA StyleSalinas-Roca, B., Rubió-Piqué, L., & Montull-López, A. (2022). Polyphenol Intake in Pregnant Women on Gestational Diabetes Risk and Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 14(18), 3753. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183753