Choice Experiment Assessment of Consumer Preferences for Yogurt Products Attributes: Evidence from Taiwan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

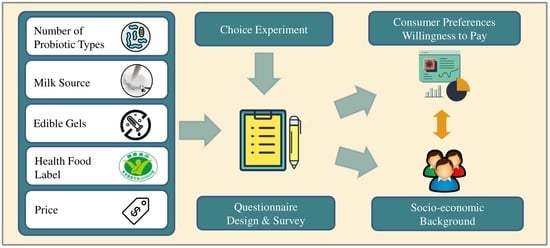

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Choice Analysis: Conceptual Framework and Statistical Model

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sample Size and Composition

3.2. Knowledge and Valuing of Each Attribute

3.3. Consumer Preferences of Yogurt Attribute Combinations

3.4. Results of CL and RPL Analysis

3.5. Respondents’ Differences in Yogurt Attribute WTP with Respect to Socio-Economic Background

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Management Implications

5.2. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

- Only five yogurt product attributes (number of probiotic types, milk source, edible gels, health food label, and price) were included, while there are other yogurt product attributes that could have been included. For example, the fat and protein content of the milk source can be adjusted by adding food processing ingredients such as milk protein concentrates, whey powder, and whey protein, resulting in changes in the texture, flavor, and nutritional composition of yogurt. Meanwhile, differences in consumer understanding and valuing of these food processing ingredients may affect consumer preferences and WTP.

- The research materials are mainly regarding medium (about 500 mL) yogurts, but there are still small (about 200 mL), large (about 900 mL), and extra-large (about 1700 mL) yogurts in the Taiwan market. It is possible to explore the influence of different specifications of yogurt on consumer preferences and motivation, consumers’ channel choices, as well as further cross-analysis and the relationship between consumers’ social and economic background.

- The results of this study showed that respondents’ consumption motive was focused on health improvement (41.6%) and nutritional supplementation (23.9%). Therefore, future studies can further explore health improvement-related attributes in depth (e.g., gastrointestinal mediation and prevention of cardiovascular diseases) and nutrition supplementation-related attributes (e.g., calcium and collagen), which should help the food industry to understand consumers’ preferences and WTP to develop healthy yogurts to meet market demand.

- The latent class model (LCM) may be used in future research to examine whether there is heterogeneity in consumer preferences for yogurt.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gómez-Gallego, C.; Gueimonde, M.; Salminen, S. The role of yogurt in food-based dietary guidelines. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76 (Suppl. S1), 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H.; Green, J.; Jacka, F.N.; Collier, F.; Berk, M.; Pasco, J.; Dawson, S.L. Fermented foods, the gut and mental health: A mechanistic overview with implications for depression and anxiety. Nutr. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.A.; Panahi, S.; Daniel, N.; Tremblay, A.; Marette, A. Yogurt and cardiometabolic diseases: A critical review of potential mechanisms. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 812–829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karwowska, Z.; Szemraj, J.; Karwowski, B.T. Antynowotworowe właściwości probiotycznych bakterii jogurtowych [Anticancer properties of probiotic yogurt bacteria]. Postepy Biochem. 2019, 65, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Wu, J.H. Flavonoids, dairy foods, and cardiovascular and metabolic health: A review of emerging biologic pathways. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 369–384. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, R.; Martin, D.A.; DiMarco, D.M.; Bolling, B.W. Evidence for the effects of yogurt on gut health and obesity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 1569–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.J.; Chen, P.C.; Lai, F.P.; Tsai, P.J.; Sheu, B.S. Probiotics-Containing Yogurt Ingestion and H. pylori Eradication Can Restore Fecal Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Dysbiosis in H. pylori-Infected Children. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 146. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, D.A.; Givens, D.I.; Lovegrove, J.A. Yogurt consumption is associated with higher nutrient intake, diet quality and favourable metabolic profile in children: A cross-sectional analysis using data from years 1–4 of the National Diet and Nutrition Survey, UK. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Livingston, K.A.; Fox, C.S.; Meigs, J.B.; Jacques, P.F. Yogurt consumption is associated with better diet quality and metabolic profile in American men and women. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Information, Inc. Yogurt Market—Growth, Trends, COVID-19 Impact, and Forecasts (2022–2027). Available online: https://reurl.cc/ErL7Ov (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Department of Economic Affairs Census and Statistics Department. Department of Economic Affairs Statistical Data Analysis System. Available online: https://dmz26.moea.gov.tw/GA/query/Query.aspx (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Hsu, J.L.; Kao, J.S. Factors affecting consumers’ fluid milk purchasing patterns in Taiwan: Product comparisons and marketing implications. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2001, 7, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Köster, E.P. Diversity in the determinants of food choice: A psychological perspective. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 70–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gullo, K.; Berger, J.; Etkin, J. Does time of day affect variety-seeking? J. Consum. Res. 2019, 46, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J.L.; Lin, Y.T. Consumption and attribute perception of fluid milk in Taiwan. Nutr. Food Sci. 2006, 36, 177–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Allenby, G.M.; Rossi, P.E. Modeling consumer demand for variety. Mark. Sci. 2002, 21, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganska, M.; Jain, D.C. Consumer preferences and product-line pricing strategies: An empirical analysis. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, Z.; Schroeder, T.C. Effects of label information on consumer willingness-to-pay for food attributes. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2009, 91, 795–809. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerkvist, C.J. Consumer preferences for food labelling attributes: Comparing direct ranking and best-worst scaling for measurement. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 29, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roininen, K.; Arvola, A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Exploring consumers’ perceptions of local food with two different qualitative techniques: Laddering and word association. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.B.; Sutton, E.H.; Hancock, N. Sugar Reduction in Yogurt Products Sold in the UK between 2016 and 2019. Nutrients 2020, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Khubber, S.; Dwivedi, M.; Misra, N.N. Strategies for lowering the added sugar in yogurts. Food Chem. 2021, 344, 128573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korada, S.K.; Yarla, N.S.; Mishra, V.; Daim, M.A.; Sharma, B.; Gm, A.; Reggi, R.; Palmery, M.; Peluso, I.; Kamal, M.A. Single probiotic versus multiple probiotics-a debate on current situation for alleviating health benefits. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 4150–4153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lambo, M.T.; Chang, X.; Liu, D. The Recent Trend in the Use of Multistrain Probiotics in Livestock Production: An Overview. Animals 2021, 11, 2805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McFarland, L.V. Efficacy of single-strain probiotics versus multi-strain mixtures: Systematic review of strain and disease specificity. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2021, 66, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ouwehand, A.C.; Invernici, M.M.; Furlaneto, F.A.; Messora, M.R. Effectiveness of multi-strain versus single-strain probiotics: Current status and recommendations for the future. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2018, 52, S35–S40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, P. Changes in bioactive milk serum proteins during milk powder processing. Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.G.; Liu, X.J.; Wang, Z.M.; Li, T.F.; Wahlqvist, M.L. Melamine-contaminated milk formula and its impact on children. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 25, 697–705. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.C.; Chen, F.L. Nephrolithiasis screening for people with self-perceived exposure to melamine-contaminated milk products in Taipei County, Taiwan. Urol. Sci. 2017, 28, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Abiega-Franyutti, P.; Freyre-Fonseca, V. Chronic consumption of food-additives lead to changes via microbiota gut-brain axis. Toxicology 2021, 464, 153001. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Lambré, C.; Leblanc, J.C.; et al. Re-evaluation of locust bean gum (E 410) as a food additive. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. J. 2017, 15, e04646. [Google Scholar]

- Burh, A.; Batra, S.; Sharma, S. Emerging Facts on Chronic Consumption of Aspartame as Food Additive. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 17, 690–698. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, S.; Sandall, A.; Smith, L.; Rossi, M.; Whelan, K. Food additive emulsifiers: A review of their role in foods, legislation and classifications, presence in food supply, dietary exposure, and safety assessment. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wu, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Hu, W. Effects of Food-Additive-Information on Consumers’ Willingness to Accept Food with Additives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Ward, R.W. Consumer Interest in Information Cues Denoting Quality, Traceability and Origin: An Application of Ordered Probit Models to Beef Labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehagia, O.; Chrysochou, P.; Chryssochoidis, G.; Krystallis, A.; Linardakis, M. European Consumers’ Perceptions, Definitions and Expectations of Traceability and the Importance of Labels, and the Differences in These Perceptions by Product Type. Sociol. Rural. 2007, 47, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowska, J.; Prandota, A.; Rejman, K.; Halicka, E.; Tul-Krzyszczuk, A. Certification labels in shaping perception of food quality-insights from Polish and Belgian urban consumers. Sustainability 2021, 13, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabella, A.; Voinea, L. Advantages and limitations of the front-of-package (FOP) labeling systems in guiding the consumers’ healthy food choice. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2013, 15, 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- The Food and Drug Administration of the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Scope of Use and Limits and Specification Standards for Food Additives. Available online: https://www.mohw.gov.tw/cp-5014-58675-1.html (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Pearson, D.; Henryks, J.; Jones, H. Organic Food: What We Know (and Do Not Know) about Consumers. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strateg. Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.A.; Yoo, H.J.; Ares, G.; Lee, H.S. Effect of thinking style and consumption purpose on food choice: A case study with yogurt using a discrete choice experiment and eye-tracking. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.C.; Chang, C.T.; Cheng, Z.H.; Chen, Y.T. Will an Organic Label Always Increase Food Consumption? It Depends on Food Type and Consumer Differences in Health Locus of Control. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Pedersen, S.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. the Impact of Organic Certification and Country of Origin on Consumer Food Choice in Developed and Emerging Economies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 72, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Akker, K.; Bartelet, D.; Brouwer, L.; Luijpers, S.; Nap, T.; Havermans, R. The impact of the nutrient-score on food choice A choice experiment in a Dutch supermarket. Appetite 2022, 168, 105664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, P.; Pomeranz, J.L.; Lizewski, L.J.; Zhang, F.F. Consumer confusion about wholegrain content and healthfulness in product labels: A discrete choice experiment and comprehension assessment. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3324–3331. Available online: https://doi-org.sw.lib.csmu.edu.tw/10.1017/S1368980020001688 (accessed on 8 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louviere, J.J.; Flynn, T.N.; Carson, R.T. Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. J. Choice Model. 2010, 3, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z. Meta-analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable food products. Appetite 2021, 163, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühl, S.; Gassler, B.; Spiller, A. Labeling strategies to overcome the problem of niche markets for sustainable milk products: The example of pasture-raised milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 5082–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, S.; Lim, J.; Streletskaya, N.A. Clean Label Trade-Offs: A Case Study of Plain Yogurt. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 704473. Available online: https://doi-org.sw.lib.csmu.edu.tw/10.3389/fnut.2021 (accessed on 12 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Teoh, S.L.; Ngorsuraches, S.; Lai, N.M.; Chaiyakunapruk, N. Consumer Preferences and Willingness to Pay for Nutraceuticals: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Value Health Reg. Issues 2021, 24, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pelsmacker, P.; Driesen, L.; Rayp, G. Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch, B. Estimation of Willingness-to-Pay: Theory, Measurement, and Application. Ph.D. Thesis, Vienna University of Economics and Business, Wien, Austria, 2005. Available online: http://epub.wu.ac.at/1934/-datadostępu:16.05.2017r (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- Tully, S.M.; Winer, R.S. The role of the beneficiary in willingness to pay for socially responsible products: A meta-analysis. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Magistris, T.; Lopéz-Galán, B. Consumers’ willingness to pay for nutritional claims fighting the obesity epidemic: The case of reduced-fat and low salt cheese in Spain. Public Health 2016, 135, 83–90. Available online: https://doi-org.sw.lib.csmu.edu.tw/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.02.004 (accessed on 12 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro, D.; Veneziani, M.; Sckokai, P.; Castellari, E. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Catechin-enriched Yogurt: Evidence from a Stated Choice Experiment. Agribusiness 2015, 31, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, K.M.; Lamb, K.E.; Abbott, G.; Worsley, T.; McNaughton, S.A. Ranking of meal preferences and interactions with demographic characteristics: A discrete choice experiment in young adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 157. Available online: https://doi-org.sw.lib.csmu.edu.tw/10.1186/s12966-020-01059-7 (accessed on 12 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- National Regulatory Database. Food Safety and Health Administration Act. Available online: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=L0040001 (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- The National Health Service, Ministry of Health and Welfare. A New Version of the “Methodology of Waist Circumference Measurement and Interpretation for Adults”. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/Pages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=1125&pid=1697 (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Lancaster, K. A new approach to consumer theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, N.; Mourato, S.; Wright, R.E. Choice Modelling Approaches: A Superior Alternative for Environmental Valuatioin? J. Econ. Surv. 2001, 15, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.; Rigby, D.; Young, T.; James, S. Consumer attitudes to genetically modified organisms in food in the UK. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001, 28, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, R.; Cullen, R.; Colombo, S. Estimating values of environmental impacts of dairy farming in New Zealand. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 2009, 52, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Viera, M.E.; van den Berg, M.; Donovan, J.; Perez-Luna, M.E.; Ospina-Rojas, D.; Handgraaf, M. Demand for healthier and higher-priced processed foods in low-income communities: Experimental evidence from Mexico City. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 95, 104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Loo, E.J.; Diem, M.N.H.; Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W. Consumer attitudes, knowledge, and consumption of organic yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan). Available online: https://www.stat.gov.tw/public/Data/169152483HCL2D3O.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2022).

- Lee, M.-S.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Peng, C.-J. Dairy foods and health in Asians: Taiwanese considerations. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 24 (Suppl. S1), S14–S20. [Google Scholar]

- Numbeo. Price Rankings by Country of Milk. 2022. Available online: https://www.numbeo.com/cost-of-living/country_price_rankings?itemId=8 (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Ballco, P.; De Magistris, T. Spanish consumer purchase behaviour and stated preferences for yoghurts with nutritional and health claims. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bimbo, F.; Bonanno, A.; Nocella, G.; Viscecchia, R.; Nardone, G.; De Devitiis, B.; Carlucci, D. Consumers’ acceptance and preferences for nutrition-modified and functional dairy products: A systematic review. Appetite 2017, 113, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, G.; Ghosh, A.P. Should We Trust Front-of-Package Labels? How Food and Brand Categorization Influence Healthiness Perception and Preference. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2020, 5, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, S. Effects of short-term food additive nutrition education including hands-on activities on food label use and processed-food consumption behaviors: Among 5th grade elementary school students. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2011, 16, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pae, M. Dietary habits and perception toward food additives according to the frequency of consumption of convenience food at convenience stores among university students in Cheongju. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2016, 21, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vatanparast, H.; Islam, N.; Patil, R.P.; Shamloo, A.; Keshavarz, P.; Smith, J.; Whiting, S. Consumption of yogurt in Canada and its contribution to nutrient intake and diet quality among Canadians. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ge, J.; Ma, Y. Urban Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for pork with certified labels: A discrete choice experiment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.A.; Schoeni, J.L.; Vegge, C.; Pane, M.; Stahl, B.; Bradley, M.; Goldman, V.S.; Burguière, P.; Atwater, G.B.; Sanders, M.E. Improving end-user trust in the quality of commercial probiotic products. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, C.M.C.; Gibson, G.R.; Rowland, I. Health benefits of probiotics: Are mixtures more effective than single strains? Eur. J. Nutr. 2011, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejero-Sariñena, S.; Barlow, J.; Costabile, A.; Gibson, G.R.; Rowland, I. Antipathogenic activity of probiotics against Salmonella Typhimurium and Clostridium difficile in anaerobic batch culture systems: Is it due to synergies in probiotic mixtures or the specificity of single strains? Anaerobe 2013, 24, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaliere, A.; Ricci, E.C.; Banterle, A. Nutrition and health claims: Who is interested? An empirical analysis of consumer preferences in Italy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 41, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Level | Variable Name | Variable Value | Expected Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of probiotic types |

| PRO1 |

| + |

| PRO2 |

| + | ||

| Milk source |

| MLK1 |

| + |

| MLK2 |

| + | ||

| Edible gels |

| GEL |

| + |

| Health food label |

| HEA |

| + |

| Price |

| FUND |

| – |

| Combination | Alternative 1 | Alternative 2 | Status Quo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute | ||||

| Number of probiotic types | 8 or more types | 5–7 types | 2–4 types | |

| Milk source | Blend (raw milk + milk powder) | 100% raw milk | Blend (raw milk + milk powder)  | |

| Edible gels | Absence | Presence | Presence | |

| Health food label | Presence | Presence | Absence | |

| Price (Medium size of about 500 mL) | Additional payment of NTD 6−10 (Original price NTD 49) | Additional payment of NTD 11−15 (Original price NTD 49) | Original price NTD 49 | |

| Please check the box | □ | □ | □ | |

| Variable | Description | Sample Size | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 170 | 39.1% |

| Female | 265 | 60.9% | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 81 | 18.6% |

| 30–39 | 129 | 29.7% | |

| 40–49 | 102 | 23.4% | |

| 50–59 | 84 | 19.3% | |

| 60 or above | 39 | 9.0% | |

| Marriage Status | Unmarried | 183 | 42.1% |

| Married (no children) | 45 | 10.3% | |

| Married (with children) | 207 | 47.6% | |

| Education level | Junior high school or below | 10 | 2.3% |

| High school and vocational school | 63 | 14.5% | |

| University and junior college | 268 | 61.6% | |

| Master | 83 | 19.1% | |

| PhD | 11 | 2.5% | |

| Average personal monthly income (NTD) | Up to NTD 20,000 | 84 | 19.3% |

| 20,001–40,000 | 144 | 33.1% | |

| 40,001–60,000 | 126 | 29.0% | |

| 60,001–80,000 | 41 | 9.4% | |

| 80,001–100,000 | 21 | 4.8% | |

| Over NTD 100,001 | 19 | 4.4% | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 31 | 7.1% |

| 18.5 ≤ BMI < 24 | 183 | 42.1% | |

| 24 ≤ BMI < 27 | 127 | 29.2% | |

| 27≤ | 46 | 10.6% | |

| Unknown | 48 | 11.0% | |

| Male waist circumference (cm) | <80 | 34 | 20.0% |

| 80≤ and <90 | 93 | 54.7% | |

| 90≤ | 30 | 17.6% | |

| Unknown | 13 | 7.6% | |

| Female waist circumference (cm) | <80 | 110 | 41.5% |

| 80≤ and <90 | 105 | 39.6% | |

| 90≤ | 15 | 5.7% | |

| Unknown | 35 | 13.2% |

| Variable | Description | Sample Size | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumption Frequency (number of purchases per month) | 1 times | 167 | 38.4% |

| 2~3 times | 176 | 40.5% | |

| 4~5 times | 52 | 12.0% | |

| 6 times or more | 40 | 9.2% | |

| Consumption Channel (Most frequently purchased channel) | convenience stores | 147 | 33.8% |

| supermarkets | 188 | 43.2% | |

| hypermarket | 89 | 20.5% | |

| others | 11 | 2.5% | |

| Consumption Motivation | for no reason | 116 | 26.7% |

| to slake hunger | 23 | 5.3% | |

| to supplement nutrition | 104 | 23.9% | |

| to improve health | 181 | 41.6% | |

| others | 11 | 2.5% |

| Description | Respondent Knowledge |

|---|---|

| How well do you know about the topic of “food labels on outer packaging”? | 3.40 |

| How well do you know about the topic of the “benefits of probiotics”? | 3.77 |

| How well do you know about the topic of “the difference between raw milk and milk powder”? | 3.16 |

| How well do you know about the topic of “the usefulness of edible gels”? | 2.70 |

| How well do you know about the topic of “health food labels”? | 3.62 |

| Description | Respondent Value |

|---|---|

| How well do you value information about “the number of probiotic types”? | 4.09 |

| How well do you value information about “raw milk or milk powder as a raw material”? | 3.88 |

| How well do you value information about the “presence or absence of edible gels”? | 3.60 |

| How well do you value information about the “presence or absence of health food label”? | 4.33 |

| How well do you value information about “product price”? | 3.89 |

| Attribute and Variable | CL | RPL | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-Value | WTP (NTD) | Coefficient | t-Value | Standard Error | t-Value | WTP (NTD) | |

| Status quo (ASC) | −0.304 | −1.993 * | −0.721 | −0.797 ** | 0.905 | 0.831 | ||

| Number of probiotic types (PRO1) | 0.148 | 1.791 *** | 5.5 | 0.218 | 2.013 ** | 0.108 | 2.255 | 3.7 |

| Number of probiotic types (PRO2) | 0.261 | 0.849 ** | 9.7 | 0.371 | 0.119 *** | 0.184 | 0.071 ** | 6.3 |

| Milk source (MLK1) | 0.098 | 0.217 | 3.6 | −0.184 | 0.441 | 0.417 | 0.583 | 3.1 |

| Milk source (MLK2) | −0.027 | −0.129 | 1.0 | −0.228 | 1.306 | 0.174 | 1.137 | 3.9 |

| Edible gels (GEL) | 0.0485 | 0.533 | 1.8 | 0.163 | −0.171 * | 0.113 | 0.285 | 2.8 |

| Health Food Label (HEA) | 0.284 | 6.576 *** | 10.5 | 0.859 | 3.292 *** | 0.261 | 3.154 *** | 14.6 |

| Price (FUND) | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.059 | 1.605 | 0.037 | |||

| Number of attribute combinations | 1305 | 1305 | ||||||

| Log–likelihood ratio | −1134.552 | −1027.933 | ||||||

| Socio-Economic Background | Number of Respondents | ASC | PRO2 | HEA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Value | t-Value | Average Value | t-Value | Average Value | t-Value | |||

| Gender | Male | 170 | −24,842 | 2.61 | 435 | 1.77 | 823 | 3.16 |

| Female | 265 | −25,276 | 551 | 632 | ||||

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 81 | −21,634 | −2.34 | 320 | 1.53 | 735 | 2.88 * |

| 30–39 | 129 | −18,955 | 379 | 611 | ||||

| 40–49 | 102 | −22,211 | 501 | 853 | ||||

| 50–59 | 84 | −20,488 | 325 | 776 | ||||

| 60 or above | 39 | −21,084 | 319 | 860 | ||||

| Marriage Status | Unmarried | 183 | −22,569 | −1.46 * | 445 | 2.44 ** | 916 | 2.34 ** |

| Married (no children) | 45 | −20,230 | 410 | 681 | ||||

| Married (with children) | 207 | −18,790 | 391 | 889 | ||||

| Education level | Junior high school or below | 10 | −21,320 | 1.89 | 544 | 2.69 * | 874 | 1.08 |

| High school and vocational school | 63 | −27,149 | 339 | 759 | ||||

| University and junior college | 268 | −20,122 | 590 | 697 | ||||

| Master | 83 | −20,456 | 424 | 714 | ||||

| PhD | 11 | −21,092 | 346 | 749 | ||||

| Average personal monthly income | Up to NTD 20,000 | 84 | −23,971 | −2.47 * | 518 | 3.18 | 640 | 2.19 * |

| 20,001–40,000 | 144 | −18,960 | 380 | 715 | ||||

| 40,001–60,000 | 126 | −20,674 | 529 | 857 | ||||

| 60,001–80,000 | 41 | −21,361 | 388 | 667 | ||||

| 80,001–100,000 | 21 | −22,622 | 472 | 464 | ||||

| Over NTD 100,001 | 19 | −20,779 | 596 | 635 | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 31 | −22,628 | 4.31 | 362 | 2.56 | 762 | 1.54 |

| 18.5 ≤ BMI < 24 | 183 | −22,300 | 290 | 765 | ||||

| 24 ≤ BMI < 27 | 127 | −22,440 | 397 | 584 | ||||

| 27≤ | 46 | −21,579 | 548 | 862 | ||||

| Unknown | 48 | −24,083 | 353 | 704 | ||||

| Male waist circumference (cm) | <80 | 34 | −19,141 | 1.19 | 419 | 0.95 | 786 | 2.43 |

| 80≤ and <90 | 93 | −24,998 | 465 | 827 | ||||

| 90≤ | 30 | −23,667 | 344 | 791 | ||||

| Unknown | 13 | −21,100 | 238 | 686 | ||||

| Female waist circumference (cm) | <80 | 110 | −23,653 | 2.73 | 313 | 1.56 | 828 | 0.98 |

| 80≤ and <90 | 105 | −22,311 | 267 | 695 | ||||

| 90≤ | 15 | −21,690 | 329 | 832 | ||||

| Unknown | 35 | −22,538 | 347 | 424 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, M.-Y.; Huang, C.-C.; Du, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-S. Choice Experiment Assessment of Consumer Preferences for Yogurt Products Attributes: Evidence from Taiwan. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3523. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173523

Chang M-Y, Huang C-C, Du Y-C, Chen H-S. Choice Experiment Assessment of Consumer Preferences for Yogurt Products Attributes: Evidence from Taiwan. Nutrients. 2022; 14(17):3523. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173523

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Min-Yen, Chien-Cheng Huang, Ying-Chi Du, and Han-Shen Chen. 2022. "Choice Experiment Assessment of Consumer Preferences for Yogurt Products Attributes: Evidence from Taiwan" Nutrients 14, no. 17: 3523. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173523

APA StyleChang, M.-Y., Huang, C.-C., Du, Y.-C., & Chen, H.-S. (2022). Choice Experiment Assessment of Consumer Preferences for Yogurt Products Attributes: Evidence from Taiwan. Nutrients, 14(17), 3523. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14173523