Role of Nutrition Information in Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for Biofortified Cereal Food: Implications for Better Health and Sustainable Diet

Abstract

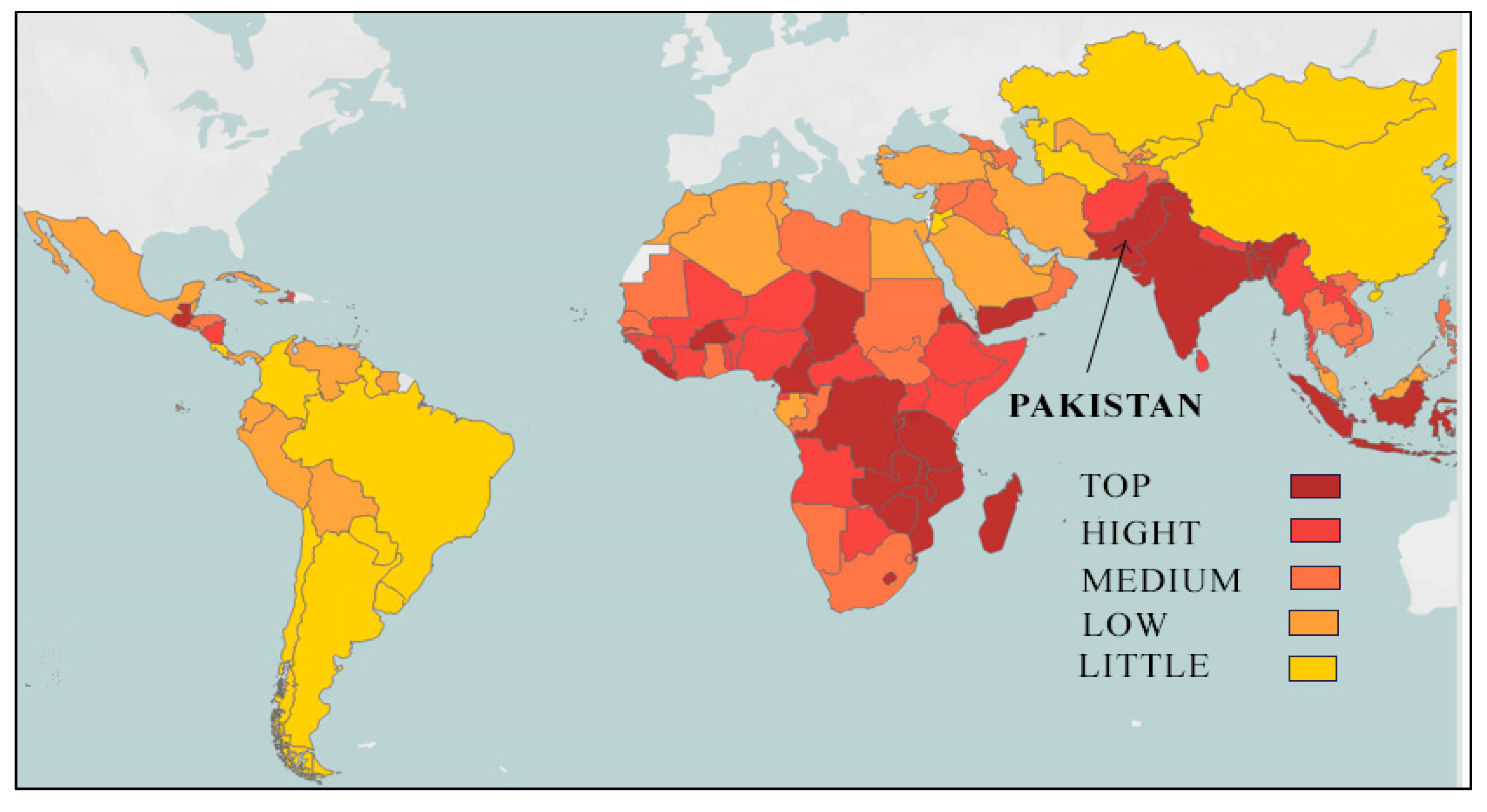

:1. Introduction

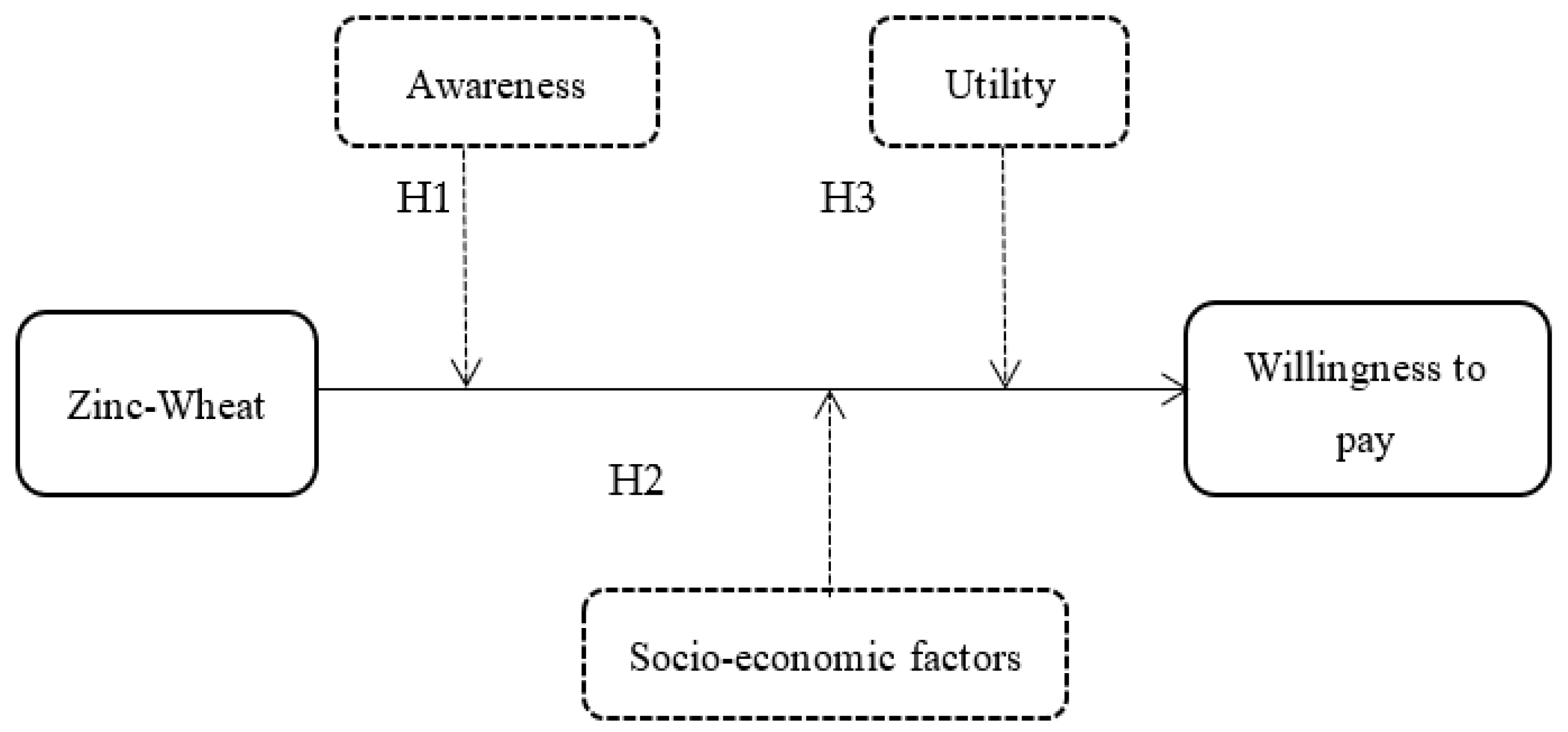

2. Conceptual Framework of the Study

3. Research Methodology

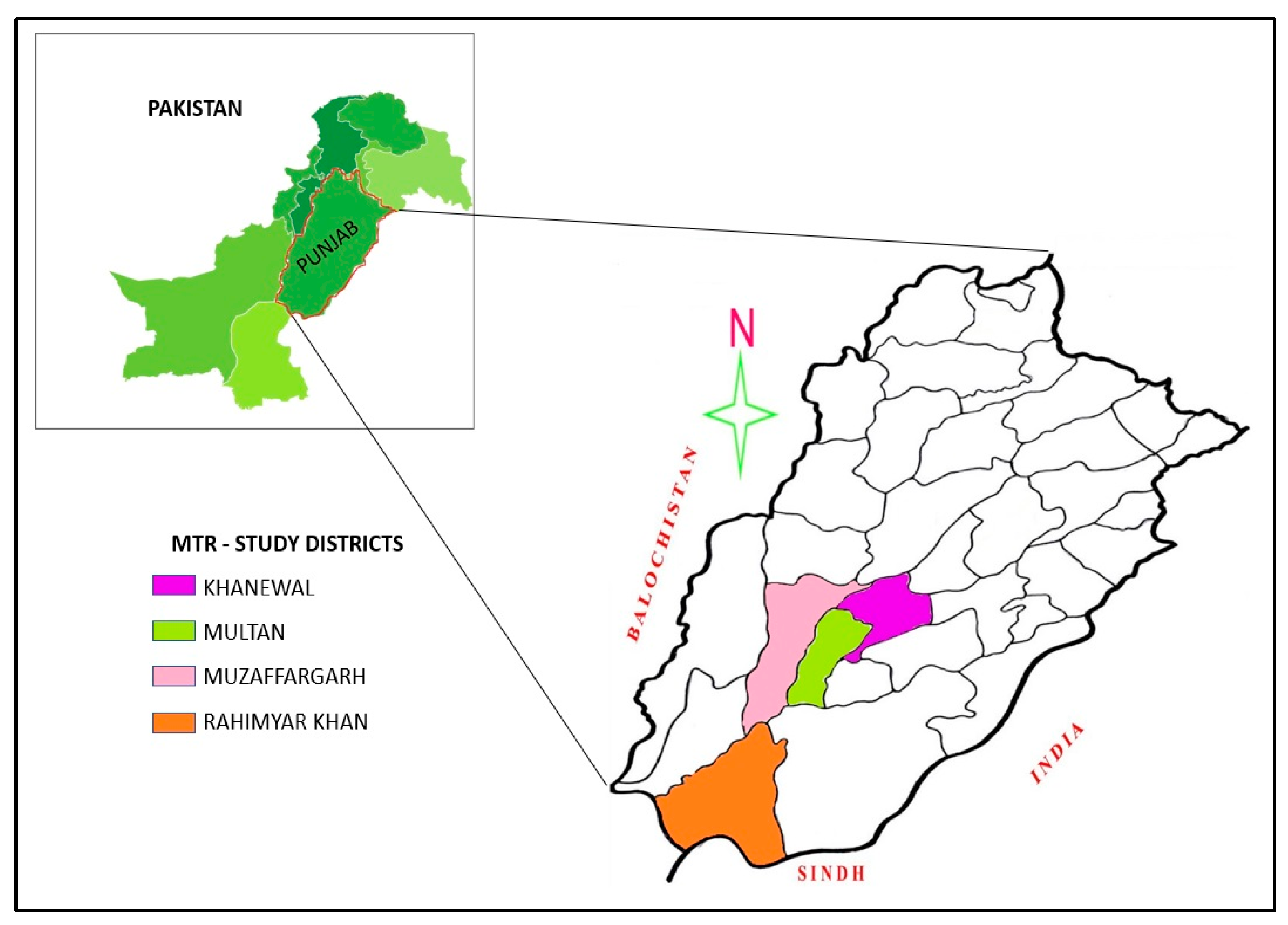

3.1. Selection of Study Districts and Respondents

3.2. Respondents’ Distribution vis-à-vis Approaches and Location

3.3. Experimental Procedure

3.3.1. Sensory Acceptability

3.3.2. Information about Nutrition

3.3.3. Choice Experiment

3.3.4. Demographic Variables

3.4. Econometric Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Variety Specification and Price Effect

4.3. Willingness to Pay (WTP) and Marginal Willingness to Pay (MWTP)

4.4. Determining Factors of Willingness to Pay

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merson, M.H.; Black, R.E.; Mills, A.J. Global Health: Diseases, Programs, Systems, and Policies; Jones & Bartlett Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2011; ISBN 1449677339. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.L.; West, K.P.; Black, R.E. The epidemiology of global micronutrient deficiencies. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66 (Suppl. S2), 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Meenakshi, J.V.; Tomlins, K.I.; Owori, C. Are consumers in developing countries willing to pay more for micronutrient-dense biofortified foods? Evidence from a field experiment in Uganda. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 93, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo, V.M.; Baker, S.K. Vitamin A deficiency and child survival in Sub-Saharan Africa: A reappraisal of challenges and opportunities. Food Nutr. Bull. 2005, 26, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwitz, A.; Kennedy, E.; Howson, C. Prevention of Micronutrient Deficiencies: Tools for Policymakers and Public Health Workers; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bain, L.E.; Awah, P.K.; Geraldine, N.; Kindong, N.P.; Sigal, Y.; Bernard, N.; Tanjeko, A.T. Malnutrition in Sub—Saharan Africa: Burden, causes and prospects. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2013, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Briel, T.; Cheung, E.; Zewari, J.; Khan, R. Fortifying food in the field to boost nutrition: Case studies from Afghanistan, Angola, and Zambia. Food Nutr. Bull. 2007, 28, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, G.; Nantel, G.; Brouwer, I.D.; Kok, F.J. Does living in an urban environment confer advantages for childhood nutritional status? Analysis of disparities in nutritional status by wealth and residence in Angola, Central African Republic and Senegal. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smuts, C.M.; Dhansay, M.A.; Faber, M.; van Stuijvenberg, M.E.; Swanevelder, S.; Gross, R.; Benadé, A.J.S. Efficacy of multiple micronutrient supplementation for improving anemia, micronutrient status, and growth in South African infants. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 653S–659S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertosun, G.M.; Cho, H.; Kapur, P.; Saraswat, K.C. A nanoscale vertical double-gate single-transistor capacitorless dram. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2008, 29, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alloway, B.J. Zinc in Soils and Crop Nutrition; International Zinc Association Communications; IZA Publ.: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak, I. Enrichment of cereal grains with zinc: Agronomic or genetic biofortification? Plant Soil 2008, 302, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotz, C.; Brown, K.H. Assessment of the risk of zinc deficiency in populations and options for its control. Food Nutr. Bull. 2004, 25, S91–S204. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Macro-Nutrients and Health: Investing in Health for Economic Development. Report of the Commission on Macro-Economics and Health World Health Organization. 2001. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42463 (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Stein, A.J. Global impacts of human mineral malnutrition. Plant Soil 2010, 335, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreini, C.; Banci, L.; Bertini, I.; Rosato, A. Zinc through the three domains of life. J. Proteome Res. 2006, 5, 3173–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadley, M.R.; White, P.J.; Hammond, J.P.; Zelko, I.; Lux, A. Zinc in plants. New Phytol. 2007, 173, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, J.E. Zinc enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998, 2, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambridge, M. Human zinc nutrition. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1344S–1349S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, U.; Clemens, S. Functions and Homeostasis of Zinc, Copper, and Nickel in Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; ISBN 3540221751. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, A.S. Discovery of human zinc deficiency: Its impact on human health and disease. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Halsted, J.A.; Nadimi, M. Syndrome of iron deficiency anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, hypogonadism, dwarfism and geophagia. Am. J. Med. 1961, 31, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saper, R.B.; Rash, R. Zinc: An essential micronutrient. Am. Fam. Physician 2009, 79, 768. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghani, S.M.; Katibeh, P.; Haghighat, M.; Moravej, H.; Asadi, S. Prevalence of zinc deficiency in 3–18 years old children in Shiraz-Iran. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2011, 13, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Bitarakwate, E.; Mworozi, E.; Kekitiinwa, A. Serum zinc status of children with persistent diarrhoea admitted to the diarrhoea management unit of Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 2003, 3, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J.B.; Hamer, D.H.; Meydani, S.N. Low zinc status: A new risk factor for pneumonia in the elderly? Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wintergerst, E.S.; Maggini, S.; Hornig, D.H. Immune-enhancing role of vitamin C and zinc and effect on clinical conditions. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2006, 50, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S. Zinc: Role in immunity, oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2009, 12, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smale, M.; Nazli, H. Time to variety change on wheat farms of Pakistan’s Punjab. Harvest. Plus Work. Pap. 2014, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. National Nutrition Survey 2018: Key Finding Report. Gov. Pakistan UNICEF Pakistan. 2018. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/pakistan/reports/national-nutrition-survey-2018-key-findings-report (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Gupta, S.; Brazier, A.K.M.; Lowe, N.M. Zinc deficiency in low- and middle-income countries: Prevalence and approaches for mitigation. J. Human Nutrit. Ditet. 2020, 33, 624–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Pakistan Annual Report 2016. 2016, pp. 1–66. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/pakistan/one-un-pakistan-annual-report-2016 (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Mahira, A.; Haseeb, K. Malnutrition Costs Pakistan US$7.6 Billion Annually, New Study Reveals. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/news/news-release/malnutrition-costs-pakistan-us76-billion-annually-new-study-reveals (accessed on 19 December 2019).

- Mottaleb, K.A.; Sonder, K.; Ridaura, S.L.; Frija, A. Wheat Consumption Dynamics in Selected Countries in Asia and Africa: Implications for Wheat Supply by 2030 and 2050; Integrated Development Program Discussion Paper no. 2; International maize and Wheat Improvement Center CIMMYT: Texcoco, Mexico, 2021; 32p. [Google Scholar]

- Plus, H. Commercialization Assessment: Zinc Wheat in Pakistan. 2019. Available online: https://nutritionconnect.org/sites/default/files/2020-01/191213_Pakistan_Zinc%20Wheat_Report_vFINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Palmgren, M.G.; Clemens, S.; Williams, L.E.; Krämer, U.; Borg, S.; Schjørring, J.K.; Sanders, D. Zinc biofortification of cereals: Problems and solutions. Trends Plant Sci. 2008, 13, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brauw, A.; Eozenou, P.; Gilligan, D.O.; Hotz, C.; Kumar, N.; Meenakshi, J.V. Biofortification, crop adoption and health information: Impact pathways in Mozambique and Uganda. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 906–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessells, K.R.; Jorgensen, J.M.; Hess, S.Y.; Woodhouse, L.R.; Peerson, J.M.; Brown, K.H. Plasma zinc concentration responds rapidly to the initiation and discontinuation of short-term zinc supplementation in healthy men. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 2128–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.; Ahmed, A.; Bhatti, M.S.; Randhawa, M.A.; Ahmad, A.; Rafaqat, R. A question mark on zinc deficiency in 185 million people in Pakistan—Possible way out. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1222–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazawal, S.; Dhingra, U.; Dhingra, P.; Dutta, A.; Deb, S.; Kumar, J.; Devi, P.; Prakash, A. Efficacy of high zinc biofortified wheat in improvement of micronutrient status, and prevention of morbidity among preschool children and women—A double masked, randomized, controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2018, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, H.; Broadley, M.R.; Joy, E.J.M.; McArdle, H.; Zaman, M.; Zia, M.; Lowe, N. The BiZiFED project: Biofortified zinc flour to eliminate deficiency in Pakistan. Nutr. Bull. 2019, 44, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- List, J.A.; Gallet, C.A. What experimental protocol influence disparities between actual and hypothetical stated values? Environ. Resour. Econ. 2001, 20, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J. A new approach to consumer theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behaviour. In Frontiers in Econometrics; Zarembka, P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ojwang, S. Effects of Integrated Nutrition Education Approaches on Production and Consumption of Orange-Fleshed Sweetpotatoes in Homa Bay County, Kenya. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Okello, J.J.; Kwikiriza, N.; Muoki, P.; Wambaya, J.; Heck, S. Effect of intensive agriculture-nutrition education and extension program adoption and diffusion of biofortified crops. J. Agric. Food Inf. 2019, 20, 254–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanou, H.B.; Osendarp, S.J.M.; Argaw, A.; De Polnay, K.; Ouédraogo, C.; Kouanda, S.; Kolsteren, P. Micronutrient powder supplements combined with nutrition education marginally improve growth amongst children aged 6–23 months in rural Burkina Faso: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNDP. High-Level Deep Dive on South Punjab Report on Conference Proceedings Government of Pakistan Government of Punjab. 2022. Available online: https://pakistan.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-04/South%20Punjab%20Deep%20Dive%20Report_Final.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Ahmed, A. South Punjab Is Most Deprived Region in Province: UNDP—Pakistan—Dawn.com. 2022. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1674084 (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Loureiro, M.L.; Umberger, W.J.; Hine, S. Testing the initial endowment effect in experimental auctions. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2003, 10, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlins, K.; Manful, J.; Gayin, J.; Kudjawu, B.; Tamakloe, I. Study of sensory evaluation, consumer acceptability, affordability and market price of rice. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, R.G.; Taylor, L.O. Unbiased value estimates for environmental goods: A cheap talk design for the contingent valuation method. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.A. Do explicit warnings eliminate the hypothetical bias in elicitation procedures? Evidence from field auctions for sportscards. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, J.A.; Sinha, P.; Taylor, M.H. Using choice experiments to value non-market goods and services: Evidence from field experiments. Adv. Econ. Anal. Policy 2006, 6, 1132–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; Schroeder, T.C. Are choice experiments incentive compatible? A test with quality differentiated beef steaks. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2004, 86, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, H.; Mugalavai, V.; Ferruzzi, M.; Onkware, A.; Ayua, E.; Duodu, K.G.; Ndegwa, M.; Hamaker, B.R. Consumer Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for Instant Cereal Products With Food-to-Food Fortification in Eldoret, Kenya. Food Nutr. Bull. 2020, 41, 224–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuirk, A.; Driscoll, P.; Alwang, J.; Huang, H. System misspecification testing and structural change in the demand for meats. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 1995, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnucan, H.W.; Xiao, H.; Hsia, C.-J.; Jackson, J.D. Effects of health information and generic advertising on US meat demand. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 1997, 79, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboob, U.; Ohly, H.; Joy, E.J.M.; Moran, V.; Zaman, M.; Lowe, N.M. Exploring community perceptions in preparation for a randomised controlled trial of biofortified flour in Pakistan. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2020, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, M.; Rigby, D.; Young, T.; James, S. Consumer attitudes to genetically modified organisms in food in the UK. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001, 28, 479–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelang, P.K.; Obare, G.A.; Kimenju, S.C. Analysis of urban consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for African Leafy Vegetables (ALVs) in Kenya: A case of Eldoret Town. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, M. Biofortification for Better Nutrition: Developing and Delivering Crops with More Impact. Ph.D. Thesis, NUI Galway, Galway, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, N.M.; Zaman, M.; Khan, M.J.; Brazier, A.K.M.; Shahzad, B.; Ullah, U.; Khobana, G.; Ohly, H.; Broadley, M.R.; Zia, M.H.; et al. Biofortified Wheat Increases Dietary Zinc Intake: A Randomised Controlled Efficacy Study of Zincol-2016 in Rural Pakistan. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Zhu, Y.; Qing, P.; Zhang, D.; Ahmed, U.I.; Xu, H.; Iqbal, M.A.; Saboor, A.; Malik, A.M.; Nazir, A.; et al. Factors Determining Consumer Acceptance of Biofortified Food: Case of Zinc-Fortified Wheat in Pakistan’s Punjab Province. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 647823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Real | Without Cheap Talk—Hypothetical | With Cheap Talk—Hypothetical | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No information regarding Nutrition | 1 | -- | -- |

| Given information about Nutrition | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Area/Region | Districts | Not Given Information | With Given Information | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real | Real | Hypoth. without Cheap Talk | Hypoth. Cheap Talk | |||

| Rural | Khanewal | 31 | 29 | 30 | 28 | 118 |

| Muzaffargarh | 29 | 32 | 30 | 29 | 120 | |

| Urban | Multan | 32 | 27 | 32 | 30 | 121 |

| Rahimyar Khan | 30 | 30 | 28 | 27 | 115 | |

| Total | 122 | 118 | 120 | 114 | 474 | |

| Used Variables | Descriptions of Variables | Full Sample | Not Given Information | With Given Information | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real | Real | Hypoth. without Cheap Talk | Hypoth. with Cheap Talk | |||

| Taste | Respondent’ preference between varieties | |||||

| Conventional wheat | % of respondents who chose conventional wheat | 48.2 | 51.6 | 50.7 | 49.6 | 50.2 |

| biofortified wheat | % of respondents who chose zinc wheat | 52.8 | 49.4 | 49.3 | 51.4 | 49.8 |

| Demographic and income variables | ||||||

| Gender | %age of male | 0.57 (0.005) | 0.43 (0.0213) | 0.498 (0.021) | 0.449 (0.012) | 0.471 (0.017) |

| Education | Schooling years | 7.287 (0.051) | 6.241 (0.0437) | 7.957 (0.0489) | 7.124 (0.053) | 6.987 (0.047) |

| Family size | Number of family members | 6.213 (0.059) | 5.789 (0.079) | 6.137 (0.081) | 6.241 (0.021) | 6.021 (0.071) |

| Children <5 yrs | Number of children under 5 years | 1.318 (0.021) | 1.298 (0.039) | 1.495 (0.026) | 1.369 (0.093) | 1.387 (0.024) |

| Breastfeed/pregnant | Number of breast-feeding/pregnant women | 0.372 (0.006) | 0.395 (0.019) | 0.323 (0.013) | 0.309 (0.015) | 0.401 (0.016) |

| Income | Household income per year-PKR | 279,000 (253,121) | 253,612 (24,846) | 312,420 (268,913) | 251,024 (264,555) | 302,180 (243,544) |

| Prev. inform | %age of respondents who have information before experiment | 0.224 (0.003) | 0.201 (0.009) | 0.198 (0.010) | 0.291 (0.012) | 0.299 (0.12) |

| Location | ||||||

| KWL | Khanewal district | 118 | 31 | 29 | 30 | 28 |

| MNT | Multan district | 120 | 29 | 32 | 30 | 29 |

| RYK | Rahim Yar Khan district | 121 | 32 | 27 | 32 | 30 |

| DGK | Dera Ghazi Khan district | 115 | 30 | 30 | 28 | 27 |

| Full Sample | Not Given Information | With Given Information | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real | Real | Hypoth. without Cheap Talk | Hypoth. with Cheap Talk | ||

| Specific constant of varieties | |||||

| Conventional wheat | 5.2134 (0.3245) | 9.2341 (1.3024) | 3.8476 (0.4972) | 3.7210 (0.9870) | 8.3649 (1.0254) |

| Zinc wheat | 4.3627 (0.3102) | 4.7261 (0.8617) | 5.1278 (0.6321) | 5.9742 (0.9421) | 6.2171 (0.9941) |

| Price effect regarding own | |||||

| Conventional wheat | −0.0425 (0.0023) | −0.3641 (0.0621) | −0.0571 (0.0021) | −0.0142 (0.0079) | −0.0312 (0.0082) |

| Zinc wheat | 0.0391 (0.0041) | −0.0092 (0.0004) | −0.0510 (0.0047) | −0.0049 (0.0006) | −0.0094 (0.0009) |

| Log-likelihood | −5431.43 | −892.61 | −925.96 | −1412.02 | −903.39 |

| Not Given Information | With Given Information | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real | Real | Hypoth. without Cheap Talk | Hypoth. with Cheap Talk | |

| Total willingness to pay | ||||

| Conventional wheat | 90 (7.4015) | 90 (6.5324) | 90 (8.2513) | 90 (7.2341) |

| Zinc wheat | 95 (9.2359) | 105 (11.2508) | 115 (11.4186) | 108 (10.5268) |

| Marginal willingness to pay | ||||

| Zinc wheat vs. conventional | 5 (5%) | 15 (16%) | 25 (27%) | 18 (20%) |

| Variety | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conventional Wheat | Biofortified Wheat | |

| Price of conventional wheat | −0.00421 ** (0.0012) | 0.00024 (0.0004) |

| Price of zinc wheat | 0.00024 (0.0035) | 0.00067 * (0.0002) |

| Gender | 0.00521 (0.4561) | 0.00211 * (0.1120) |

| Education | 0.08721 (0.0371) | 0.02371 ** (0.0312) |

| Family size | −0.04102 ** (0.0420) | −0.31207 (0.0517) |

| Children <5 yrs | 0.23866 (0.2356) | 0.34502 ** (0.0689) |

| Breast feed/ pregnant | 0.04213 (0.0412) | 0.76852 * (0. 3514) |

| Income | 0.00524 (0.1023) | 4.96584 * (0.0239) |

| Taste-preference | 0.51225 (0.0681) | 0.84534 (0.1354) |

| Prev. inform | −1.38916 (0.3816) | −0.82347 (0.0612) |

| KWL | −0.94263 (0.0681) | 0.57630 * (0.0325) |

| MNT | −0.74233 (0.0281) | 0.47031 * (0.1320) |

| RYK | −0.64063 (0.1681) | 0.07630 ** (0.2115) |

| DGK | −0.84001 (0.2981) | 0.43330 ** (0.0624) |

| Constant | 3.94528 * (0.2205) | 5.23404 *** (0.0952) |

| Log-likelihood | −869.21350 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizwan, M.; Abbas, A.; Xu, H.; Ahmed, U.I.; Qing, P.; He, P.; Iqbal, M.A.; Shahzad, M.A. Role of Nutrition Information in Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for Biofortified Cereal Food: Implications for Better Health and Sustainable Diet. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163352

Rizwan M, Abbas A, Xu H, Ahmed UI, Qing P, He P, Iqbal MA, Shahzad MA. Role of Nutrition Information in Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for Biofortified Cereal Food: Implications for Better Health and Sustainable Diet. Nutrients. 2022; 14(16):3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163352

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizwan, Muhammad, Azhar Abbas, Hui Xu, Umar Ijaz Ahmed, Ping Qing, Puming He, Muhammad Amjed Iqbal, and Muhammad Aamir Shahzad. 2022. "Role of Nutrition Information in Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for Biofortified Cereal Food: Implications for Better Health and Sustainable Diet" Nutrients 14, no. 16: 3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163352

APA StyleRizwan, M., Abbas, A., Xu, H., Ahmed, U. I., Qing, P., He, P., Iqbal, M. A., & Shahzad, M. A. (2022). Role of Nutrition Information in Acceptance and Willingness to Pay for Biofortified Cereal Food: Implications for Better Health and Sustainable Diet. Nutrients, 14(16), 3352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14163352