Association between Dietary Niacin Intake and Migraine among American Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

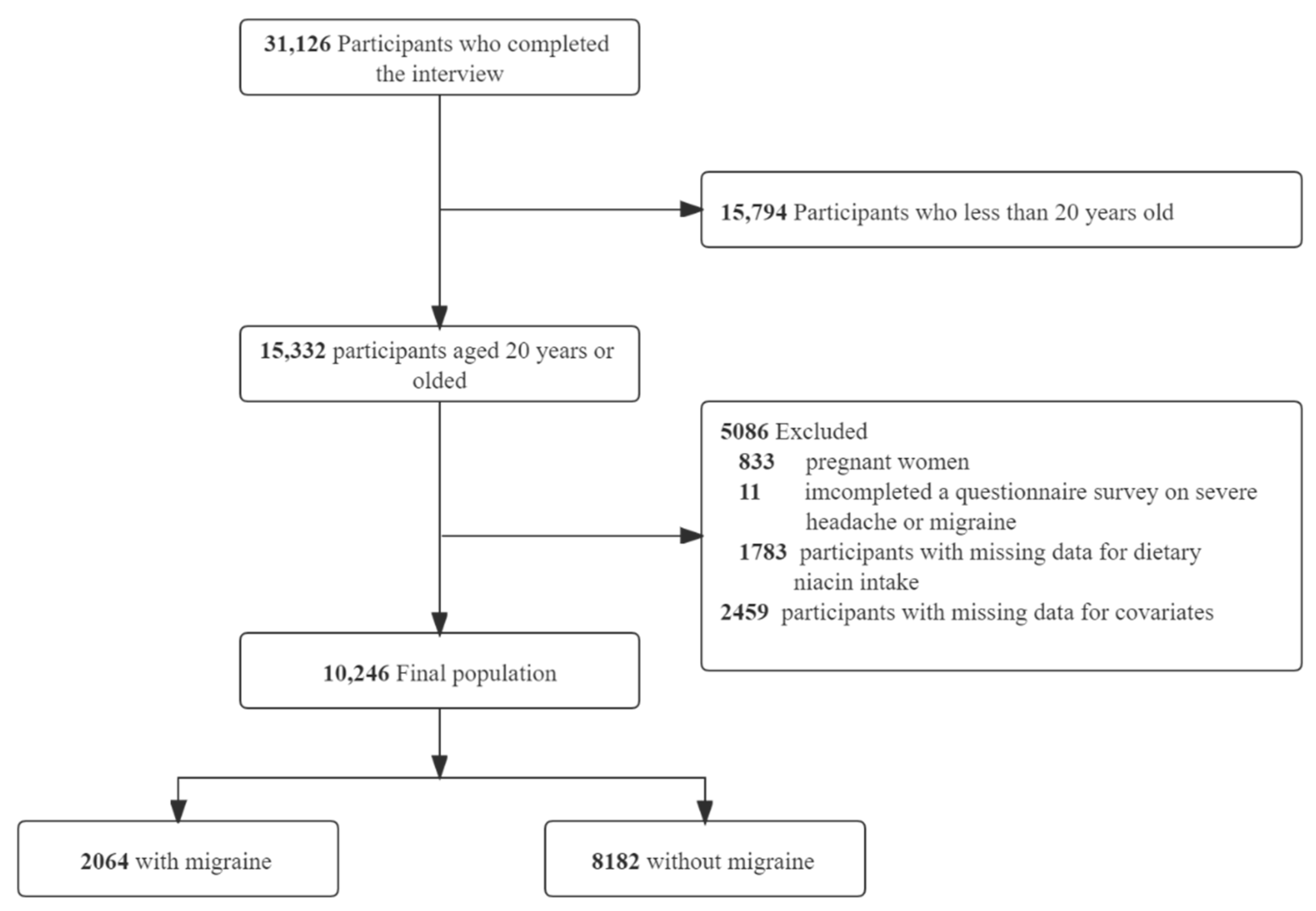

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

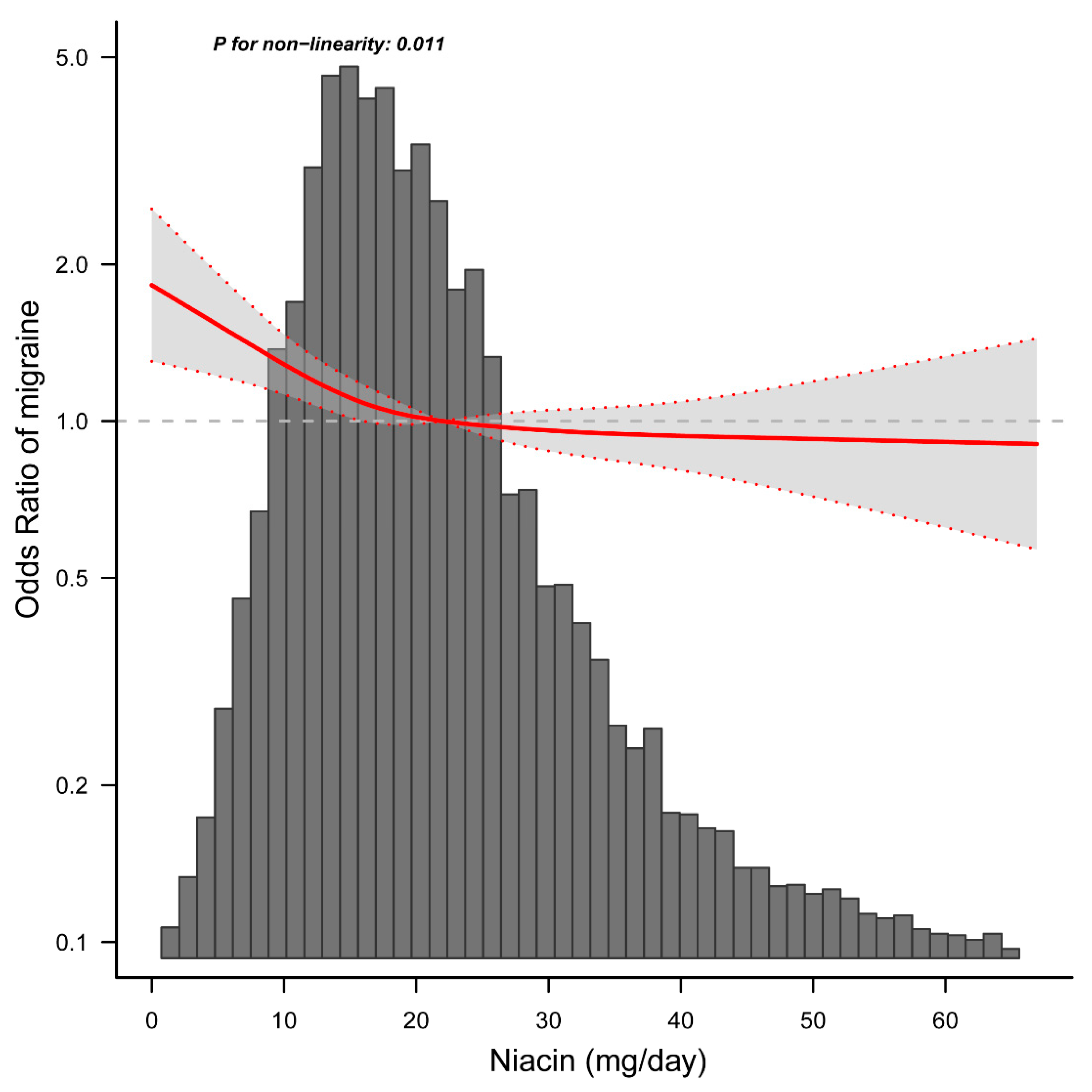

3.3. Relationship between Dietary Niacin Intake and Migraine

3.4. Stratified Analyses Based on Additional Variables

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. Neurol. 2018, 17, 954–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Steiner, T.J.; Stovner, L.J.; Vos, T. GBD 2015: Migraine is the third cause of disability in under 50s. J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gazerani, P. Migraine and Diet. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.T.; Vij, B. Diet, and Headache: Part 1. Headache 2016, 56, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.T.; Vij, B. Diet, and Headache: Part 2. Headache 2016, 56, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.H.; Wang, M.X.; Kang, L.X.; Fu, J.M.; Zhou, H.B.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Li, X.T.; Zhao, Y.S. Dietary Intake of Calcium and Magnesium in Relation to Severe Headache or Migraine. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 653765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.H.; Zhou, H.B.; Li, X.; Wang, M.X.; Kang, L.X.; Fu, J.M.; Li, X.; Li, X.T.; Zhao, Y.S. Association Between Dietary Iron Intake and Serum Ferritin and Severe Headache or Migraine. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 685564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, J.B.; Meyer-Ficca, M.L. Niacin. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 83, 83–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirinen, E.; Auranen, M.; Khan, N.A.; Brilhante, V.; Urho, N.; Pessia, A.; Hakkarainen, A.; Kuula, J.; Heinonen, U.; Schmidt, M.S.; et al. Niacin Cures Systemic NAD(+) Deficiency and Improves Muscle Performance in Adult-Onset Mitochondrial Myopathy. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 1078–1090.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velling, D.A.; Dodick, D.W.; Muir, J.J. Sustained-release niacin for prevention of migraine headache. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2003, 78, 770–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prousky, J.; Seely, D. The treatment of migraines and tension-type headaches with intravenous and oral niacin (nicotinic acid): A systematic review of the literature. Nutr. J. 2005, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borkum, J.M. Brain Energy Deficit as a Source of Oxidative Stress in Migraine: A Molecular Basis for Migraine Susceptibility. Neurochem. Res. 2021, 46, 1913–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES Survey Methods and Analytic Guidelines. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/AnalyticGuidelines.aspx (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Zipf, G.; Chiappa, M.; Porter, K.S.; Ostchega, Y.; Lewis, B.G.; Dostal, J. National health and nutrition examination survey: Plan and operations, 1999–2010. Vital Health Stat 1 2013, 56, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health & Human Services. Office of Extramural Research. Available online: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/hs/hs_policies.htm (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA); Agriculture Research Service FSRG. Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 5.0. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg (accessed on 12 March 2022).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). MEC In-Person Dietary Interviewers Procedures Manual. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/dietary_mec.pdf (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Slavin, M.; Li, H.; Khatri, M.; Frankenfeld, C. Dietary magnesium and migraine in adults: A cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2004. Headache 2021, 61, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.Q.; Estus, S.; Smith, J.H. Association Between Overall and Mentholated Cigarette Smoking With Headache in a Nationally Representative Sample. Headache 2016, 56, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlin, B.L.; Rosso, A.L.; Rapoport, A.M.; Scher, A.I. Obesity and migraine: The effect of age, gender, and adipose tissue distribution. Headache 2010, 50, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricultural ruralural Research Service; US Department of Agriculture. What We Eat in America: Data Tables. Available online: https://www.ars.usda.gov/northeast-area/beltsville-md-bhnrc/beltsville-human-nutrition-research-center/food-surveys-research-group/docs/wweia-data-tables/ (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Yang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.; Wen, D.; Chen, W.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, Z. Association Between Preadmission Metformin Use and Outcomes in Intensive Care Unit Patients With Sepsis and Type 2 Diabetes: A Cohort Study. Front. Med. Lausanne 2021, 8, 640785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedye, A. Hypothesized treatment for migraines using low doses of tryptophan, niacin, calcium, caffeine, and acetylsalicylic acid. Med. Hypotheses 2001, 56, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, M.; Hoffman, R. The Mediterranean diet: Health, science and society. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113 (Suppl. S2), S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arab, A.; Khorvash, F.; Karimi, E.; Hadi, A.; Askari, G. Associations between adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern and frequency, duration, and severity of migraine headache: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simopoulos, A.P. Evolutionary aspects of diet: The omega-6/omega-3 ratio and the brain. Mol. Neurobiol. 2011, 44, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, A.E.; Shaikh, S.R.; Slade, G.D. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and headache in the U.S. population. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2018, 135, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi Jahromi, S.; Ghorbani, Z.; Martelletti, P.; Lampl, C.; Togha, M. Association of diet and headache. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anthony, M.; Lance, J.W. Plasma serotonin in patients with chronic tension headaches. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1989, 52, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiller, C.; May, A.; Limmroth, V.; Jüptner, M.; Kaube, H.; Schayck, R.V.; Coenen, H.H.; Diener, H.C. Brain stem activation in spontaneous human migraine attacks. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahra, A.; Matharu, M.S.; Buchel, C.; Frackowiak, R.S.; Goadsby, P.J. Brainstem activation specific to migraine headache. Lancet 2001, 357, 1016–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, L.H.; May, A. The migraine generator revisited: Continuous scanning of the migraine cycle over 30 days and three spontaneous attacks. Brain 2016, 139, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, R.K.; Granner, D.K.; Mayes, P.A.; Rodwell, V.W. Harper’s Bio-Chemistry, 25th ed.; Appleton and Lange: Stamford, CT, USA, 2000; pp. 336–338, 352–354, 629–631. [Google Scholar]

- Barbiroli, B.; Montagna, P.; Cortelli, P.; Funicello, R.; Iotti, S.; Monari, L.; Pierangeli, G.; Zaniol, P.; Lugaresi, E. Abnormal brain and muscle energy metabolism shown by 31P magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients affected by migraine with aura. Neurology 1992, 42, 1209–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, R.; Tonon, C.; Testa, C.; Manners, D.; Barbiroli, B. Energy metabolism in migraine. Neurol. Sci. 2006, 27 (Suppl. S2), S82–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagna, P.; Cortelli, P.; Barbiroli, B. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies in migraine. Cephalalgia 1994, 14, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagna, P.; Cortelli, P.; Lodi, R.; Barbiroli, B. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy of episodic ataxia type 2 and migraine. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47, 838–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacquegna, T.; Lodi, R.; De Carolis, P.; Tinuper, P.; Cortelli, P.; Zaniol, P.; Funicello, R.; Montagna, P.; Barbiroli, B. Brain energy metabolism studied by 31P-MR spectroscopy in a case of migraine with prolonged aura. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1992, 86, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fila, M.; Chojnacki, C.; Chojnacki, J.; Blasiak, J. Nutrients to Improve Mitochondrial Function to Reduce Brain Energy Deficit and Oxidative Stress in Migraine. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkum, J.M. Migraine Triggers and Oxidative Stress: A Narrative Review and Synthesis. Headache 2016, 56, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji, S.H.; Qin, S.; Zhang, L.; Kamanna, V.S.; Kashyap, M.L. Niacin inhibits vascular oxidative stress, redox-sensitive genes, and monocyte adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis 2009, 202, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buse, D.C.; Loder, E.W.; Gorman, J.A.; Stewart, W.F.; Reed, M.L.; Fanning, K.M.; Serrano, D.; Lipton, R.B. Sex differences in the prevalence, symptoms, and associated features of migraine, probable migraine and other severe headache: Results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) Study. Headache 2013, 53, 1278–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, R.L.; Mossavar-Rahmani, Y.; Huang, Y.; Van Horn, L.; Beresford, S.A.; Caan, B.; Tinker, L.; Schoeller, D.; Bingham, S.; Eaton, C.B.; et al. Evaluation and comparison of food records, recalls, and frequencies for energy and protein assessment by using recovery biomarkers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Subar, A.F.; Kipnis, V.; Troiano, R.P.; Midthune, D.; Schoeller, D.A.; Bingham, S.; Sharbaugh, C.O.; Trabulsi, J.; Runswick, S.; Ballard-Barbash, R.; et al. Using intake biomarkers to evaluate the extent of dietary misreporting in a large sample of adults: The OPEN study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 158, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Niacin Intake, mg/d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Q1 (≤12.3) | Q2 (12.4–18.3) | Q3 (18.4–26.2) | Q4 (≥26.3) | p-Value | |

| NO. | 10,246 | 1971 | 2494 | 2746 | 3035 | |

| Age (year), Mean (SD) | 50.5 (18.5) | 54.1 (18.9) | 53.0 (18.4) | 50.6 (18.2) | 45.9 (17.5) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Male | 5159 (50.4) | 591 (30.0) | 992 (39.8) | 1422 (51.8) | 2154 (71.0) | |

| Female | 5087 (49.6) | 1380 (70.0) | 1502 (60.2) | 1324 (48.2) | 881 (29.0) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Married or living with a partner | 6411 (62.6) | 1120 (56.8) | 1562 (62.6) | 1823 (66.4) | 1906 (62.8) | |

| Living alone | 3835 (37.4) | 851 (43.2) | 932 (37.4) | 923 (33.6) | 1129 (37.2) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 5364 (52.4) | 859 (43.6) | 1276 (51.2) | 1498 (54.6) | 1731 (57.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 1887 (18.4) | 432 (21.9) | 460 (18.4) | 447 (16.3) | 548 (18.1) | |

| Mexican American | 2231 (21.8) | 520 (26.4) | 574 (23.0) | 600 (21.8) | 537 (17.7) | |

| Others | 764 (7.5) | 160 (8.1) | 184 (7.4) | 201 (7.3) | 219 (7.2) | |

| Education level (year), n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| < 9 | 1490 (14.5) | 456 (23.1) | 397 (15.9) | 377 (13.7) | 260 (8.6) | |

| 9–12 | 4097 (40.0) | 830 (42.1) | 1002 (40.2) | 1084 (39.5) | 1181 (38.9) | |

| >12 | 4659 (45.5) | 685 (34.8) | 1095 (43.9) | 1285 (46.8) | 1594 (52.5) | |

| Family income, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Low | 2827 (27.6) | 755 (38.3) | 707 (28.3) | 653 (23.8) | 712 (23.5) | |

| Medium | 3983 (38.9) | 758 (38.5) | 999 (40.1) | 1119 (40.8) | 1107 (36.5) | |

| High | 3436 (33.5) | 458 (23.2) | 788 (31.6) | 974 (35.5) | 1216 (40.1) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Never | 5168 (50.4) | 1049 (53.2) | 1281 (51.4) | 1392 (50.7) | 1446 (47.6) | |

| Current | 2294 (22.4) | 437 (22.2) | 512 (20.5) | 585 (21.3) | 760 (25.0) | |

| Former | 2784 (27.2) | 485 (24.6) | 701 (28.1) | 769 (28.0) | 829 (27.3) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Sedentary | 4355 (42.5) | 1061 (53.8) | 1112 (44.6) | 1137 (41.4) | 1045 (34.4) | |

| Moderate | 2905 (28.4) | 501 (25.4) | 738 (29.6) | 806 (29.4) | 860 (28.3) | |

| Vigorous | 2986 (29.1) | 409 (20.8) | 644 (25.8) | 803 (29.2) | 1130 (37.2) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2778 (27.1) | 619 (31.4) | 747 (30.0) | 772 (28.1) | 640 (21.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1022 (10.0) | 241 (12.2) | 268 (10.7) | 270 (9.8) | 243 (8.0) | <0.001 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 333 (3.3) | 88 (4.5) | 101 (4.0) | 79 (2.9) | 65 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Coronary heart disease, n (%) | 487 (4.8) | 103 (5.2) | 127 (5.1) | 128 (4.7) | 129 (4.3) | 0.341 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), Mean (SD) | 28.4 (6.2) | 28.6 (6.20 | 28.3 (6.4) | 28.5 (6.1) | 28.2 (6.1) | 0.080 |

| Calorie consumption (kcal/d), Mean (SD) | 2120.4 (1028.6) | 1235.6 (527.7) | 1750.3 (578.8) | 2158.9 (687.8) | 2964.4 (1163.3) | <0.001 |

| Protein consumption (g/d), Mean (SD) | 79.6 (42.0) | 40.1 (18.0) | 61.6 (19.4) | 80.8 (23.6) | 119.1 (45.7) | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrate consumption (g/d), Mean (SD) | 262.2 (134.6) | 166.4 (84.2) | 223.4 (94.0) | 268.7 (105.0) | 350.4 (156.0) | <0.001 |

| Fat consumption (g/d), Mean (SD) | 79.0 (46.2) | 45.0 (24.6) | 66.0 (29.7) | 81.0 (35.6) | 109.9(55.6) | <0.001 |

| Dietary supplements taken, n (%) | 5179 (50.5) | 919 (46.6) | 1328 (53.2) | 1413 (51.5) | 1519 (50.0) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dl), Median (IQR) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.6) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.2 (0.1, 0.4) | <0.001 |

| migraine, n (%) | 2064 (20.1) | 488 (24.8) | 518 (20.8) | 518 (18.9) | 540 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Variables | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.98 (0.97–0.98) | <0.001 | Physical activity, n (%) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | Sedentary | 1(reference) | |||

| Male | 1(reference) | Moderate | 0.84 (0.75–0.95) | 0.005 | |

| Female | 2.16 (1.96–2.39) | <0.001 | Vigorous | 0.82 (0.73–0.92) | 0.001 |

| Marital status, n (%) | Hypertension, n (%) | ||||

| Married or living with a partner | No | 1(reference) | |||

| Living alone | 1.11 (1.00–1.22) | 0.045 | Yes | 0.96 (0.87–1.08) | 0.520 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | Diabetes, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1(reference) | No | 1(reference) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 1.30 (1.14–1.48) | <0.001 | Yes | 0.91 (0.78–1.08) | 0.290 |

| Mexican American | 1.24 (1.09–1.40) | 0.001 | Stroke, n (%) | ||

| Others | 1.38 (1.15–1.66) | <0.001 | No | 1(reference) | |

| Education level (years), n (%) | Yes | 1.18 (0.91–1.53) | 0.216 | ||

| <9 | 1(reference) | Coronary heart disease, n (%) | |||

| 9–12 | 1.13 (0.98–1.31) | 0.102 | No | 1(reference) | |

| >12 | 0.88 (0.76–1.01) | 0.075 | Yes | 0.64 (0.5–0.83) | 0.001 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.02 (1.01–1.03) | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 1(reference) | Calorie consumption (kcal/d) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.521 | |

| Current | 1.29 (1.15–1.45) | <0.001 | Protein consumption (g/d) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.012 |

| Former | 0.69 (0.61–0.78) | <0.001 | Carbohydrate consumption (g/d) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.051 |

| Family income, n (%) | Fat consumption (g/d) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.600 | ||

| Low | 1(reference) | Niacin consumption (mg/d) | 0.99 (0.99–1.00) | <0.001 | |

| Medium | 0.73 (0.65–0.82) | <0.001 | Dietary supplements taken, n (%) | 0.80 (0.73–0.88) | <0.001 |

| High | 0.53 (0.47–0.6) | <0.001 | C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 1.04 (1.00–1.09) | 0.066 |

| Quartiles | OR (95% CI) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Crude | p-Value | Model 1 | p-Value | Model 2 | p-Value | Model 3 | p-Value | |

| Dietary niacin (mg/day) | |||||||||

| Q1 (≤12.3) | 1971 | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | 1(Ref) | ||||

| Q2 (12.4–18.3) | 2494 | 0.80 (0.69–92) | 0.002 | 0.86 (0.75–1.00) | 0.051 | 0.85 (0.73–0.98) | 0.030 | 0.83 (0.72–0.97) | 0.019 |

| Q3 (18.4–26.2) | 2746 | 0.71 (0.61–0.81) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.69–0.93) | 0.003 | 0.76 (0.65–0.89) | 0.001 | 0.74 (0.63–0.87) | <0.001 |

| Q4 (≥26.3) | 3035 | 0.66 (0.57–0.76) | <0.001 | 0.80 (0.68–0.93) | 0.004 | 0.72 (0.59–0.88) | 0.001 | 0.72 (0.58–0.88) | 0.001 |

| Trend test | 10,246 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| Niacin Intake mg/day | Adjusted Model | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| <21.0 | 0.975 (0.956–0.994) | 0.011 |

| ≥21.0 | 0.998 (0.987–1.009) | 0.692 |

| Log-likelihood ratio test | 0.004 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Dong, Z.; Yu, S. Association between Dietary Niacin Intake and Migraine among American Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153052

Liu H, Wang L, Chen C, Dong Z, Yu S. Association between Dietary Niacin Intake and Migraine among American Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients. 2022; 14(15):3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153052

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Huanxian, Lu Wang, Chunfu Chen, Zhao Dong, and Shengyuan Yu. 2022. "Association between Dietary Niacin Intake and Migraine among American Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey" Nutrients 14, no. 15: 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153052

APA StyleLiu, H., Wang, L., Chen, C., Dong, Z., & Yu, S. (2022). Association between Dietary Niacin Intake and Migraine among American Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutrients, 14(15), 3052. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14153052