Rapidly Increasing Serum 25(OH)D Boosts the Immune System, against Infections—Sepsis and COVID-19

Abstract

1. Introduction

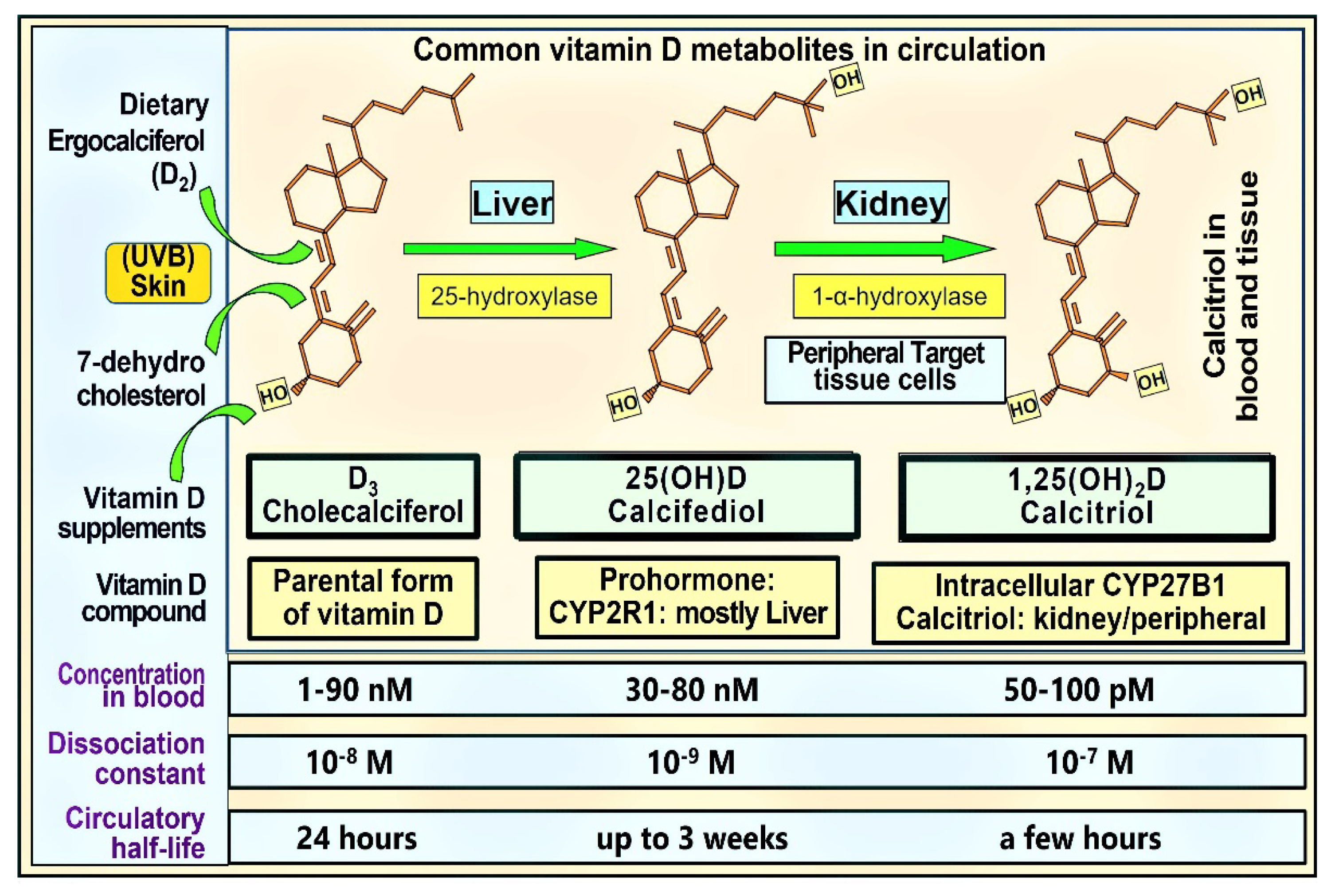

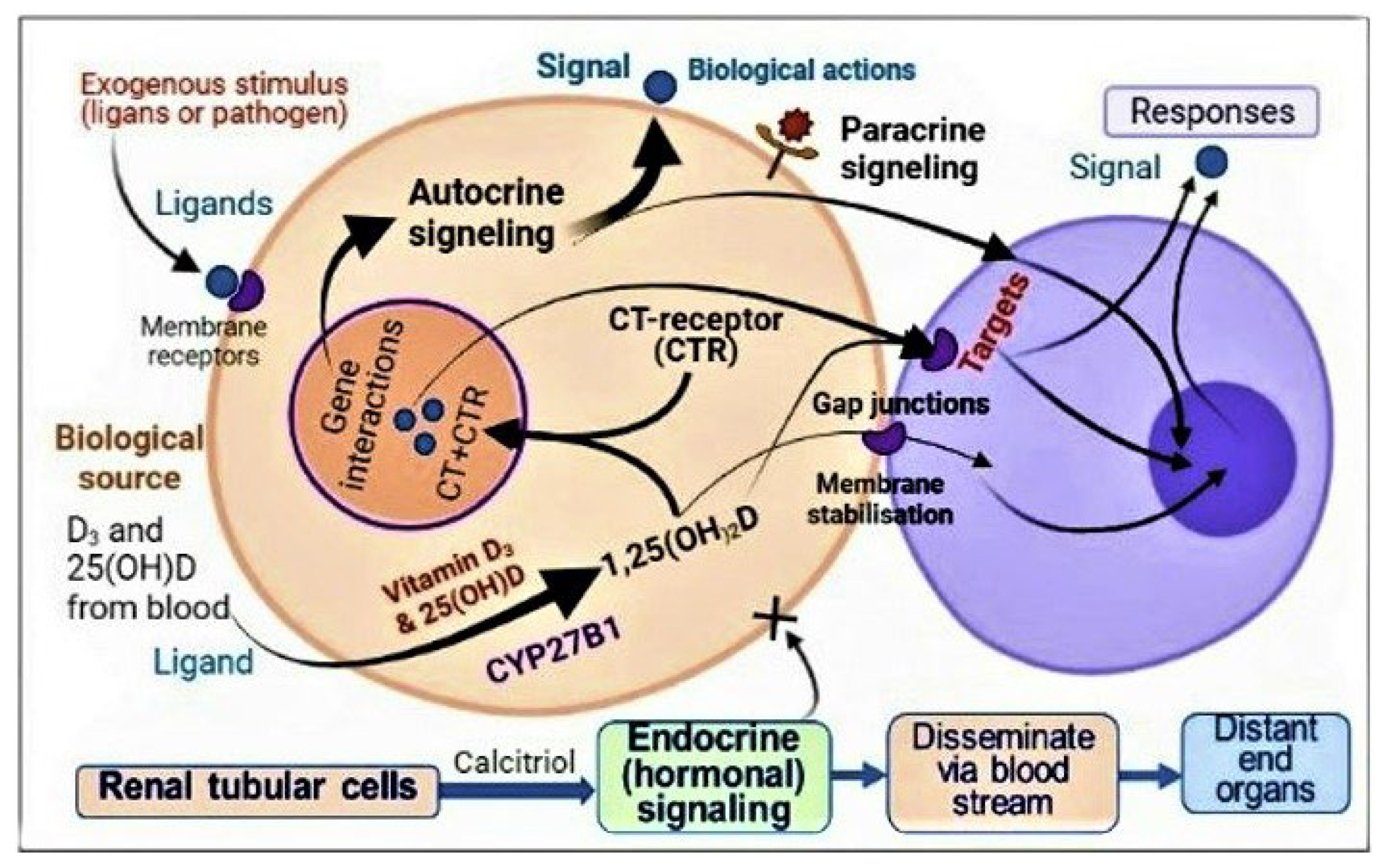

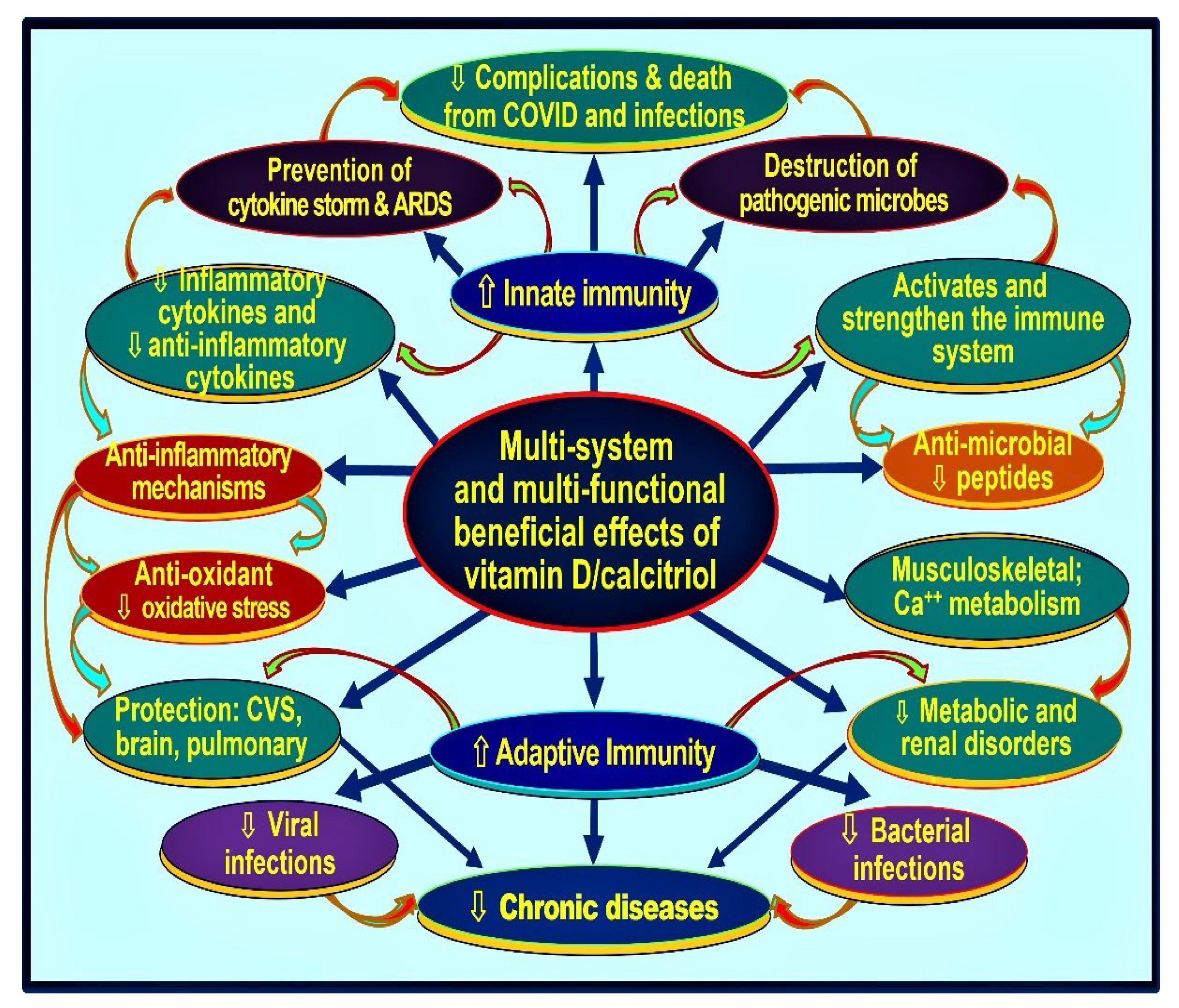

1.1. Hormonal Actions of Calcitriol—Vitamin D Metabolism

1.2. Biological Differences: Hormonal Form in the Blood vs. Target Tissue Calcitriol Concentration and Gene Regulation

1.3. Non-Genomic Actions of Vitamin D

1.4. The Importance of Administration of Vitamin D3 in Those with Renal Failure

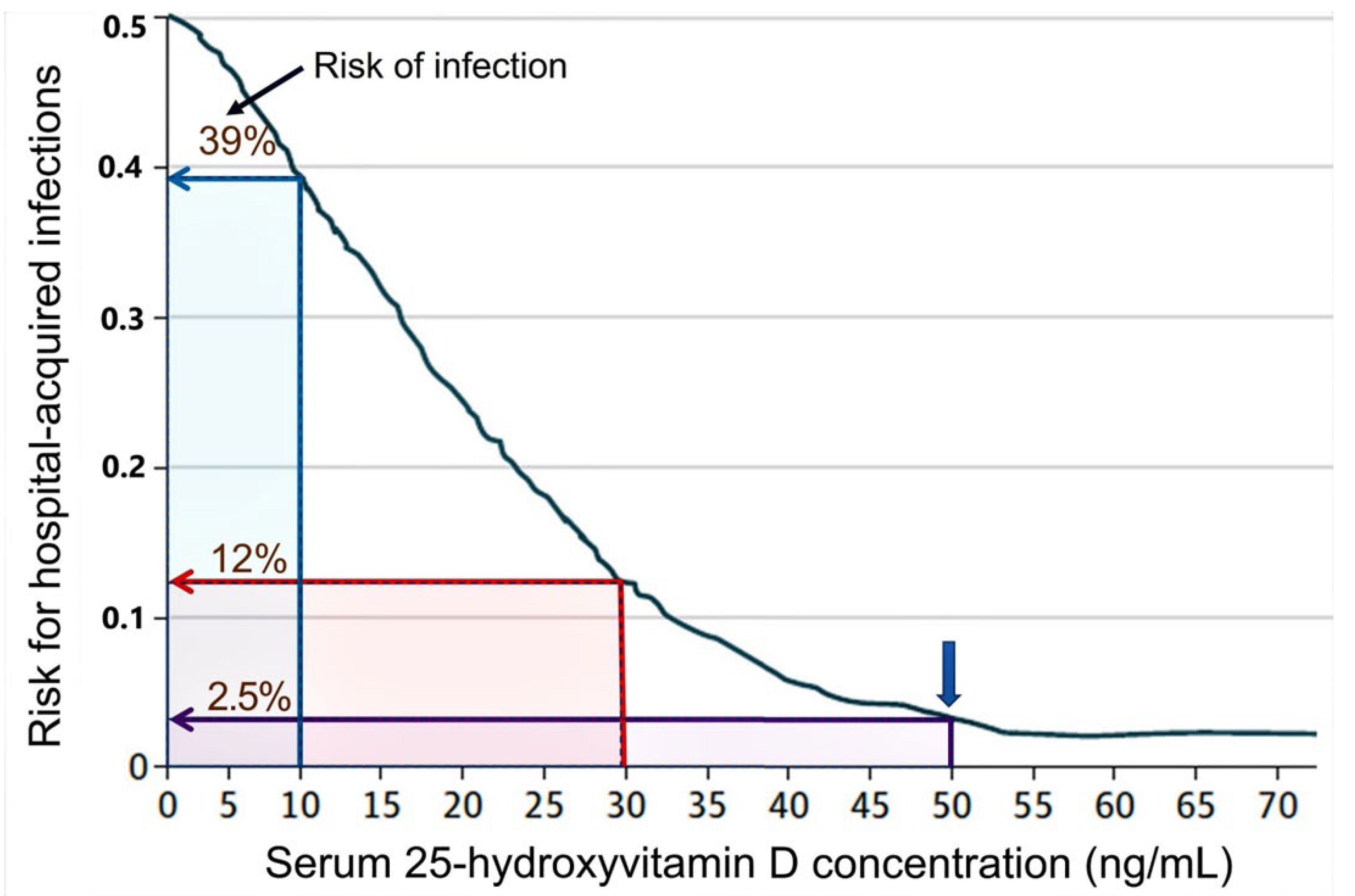

1.5. The Rationale for the Need for Universal Minimum Serum 25(OH)D Concentration

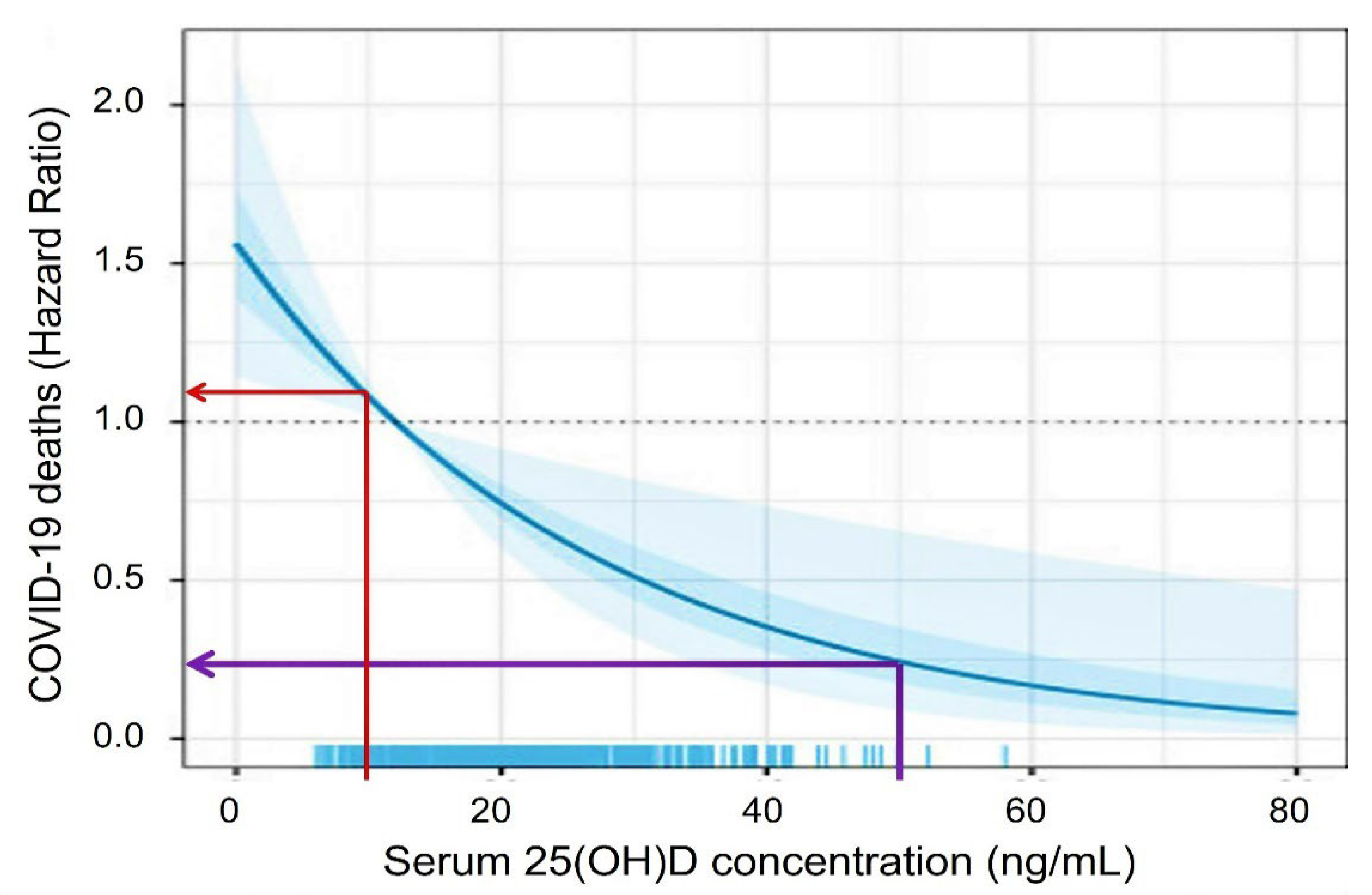

2. Vitamin D—Serum 25(OH)D Concentrations Necessary to Overcome Infections

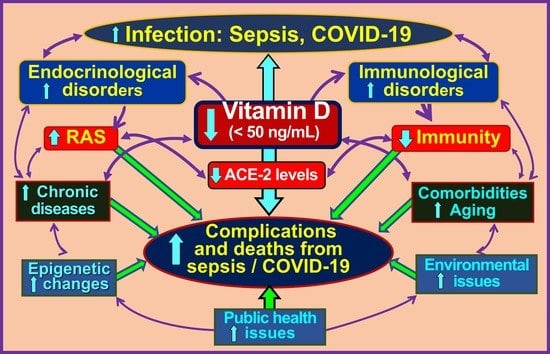

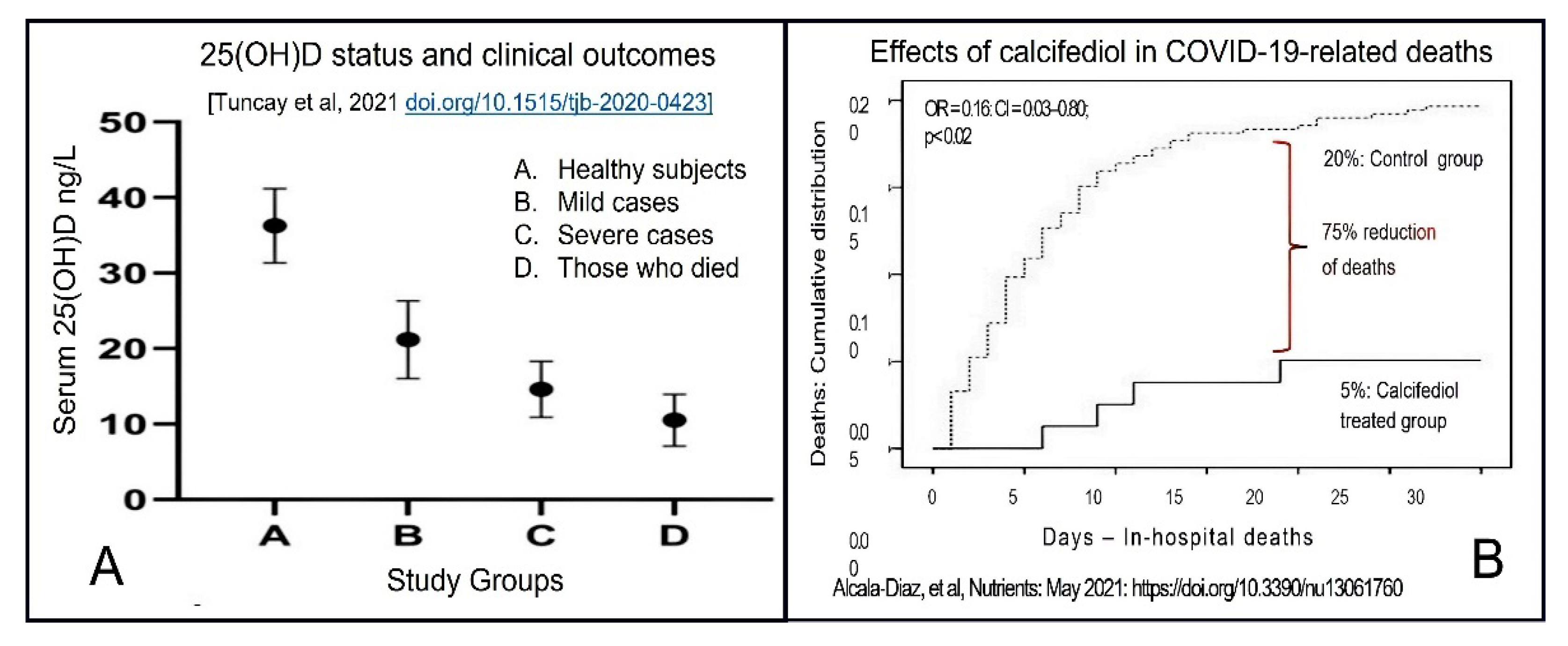

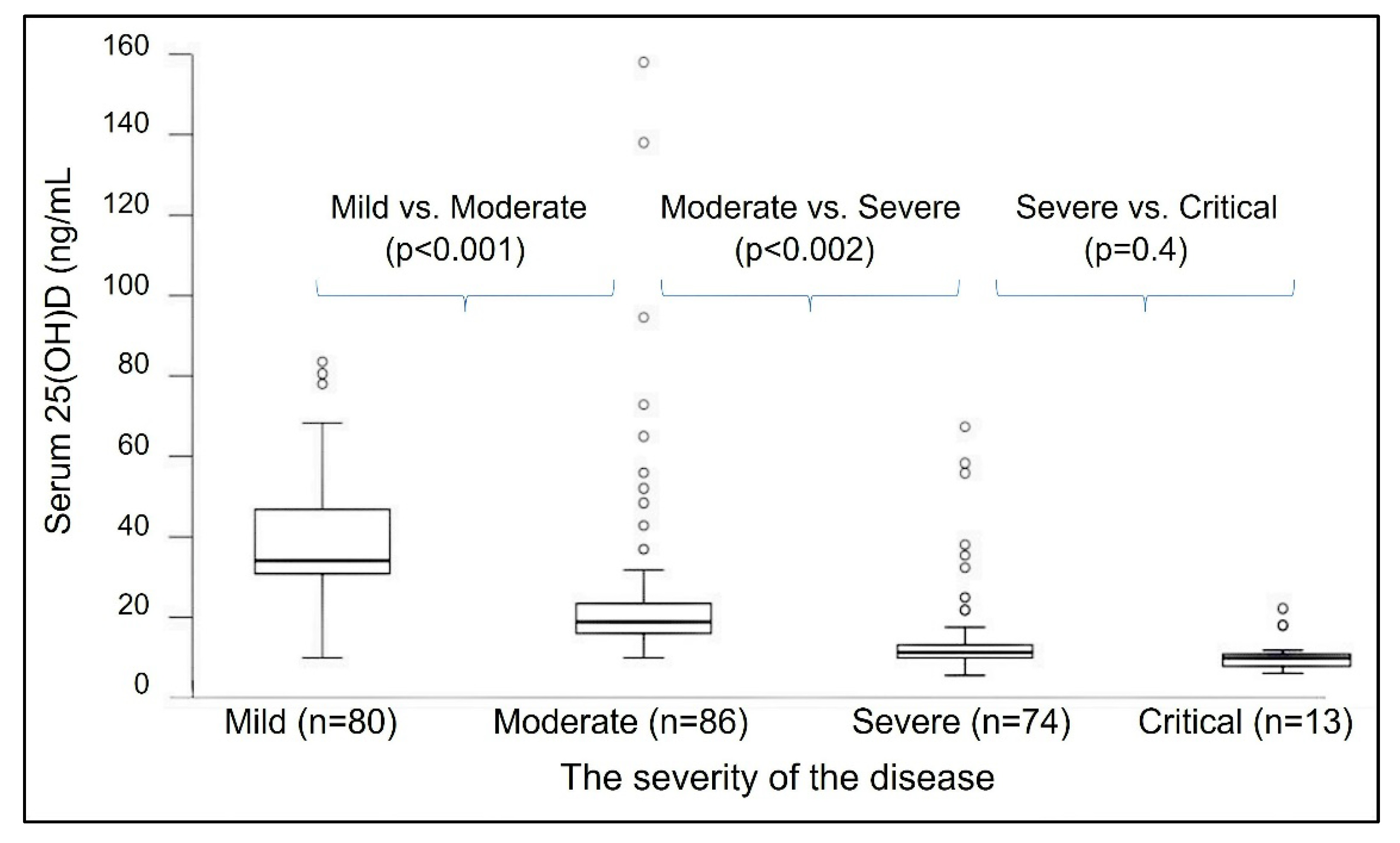

2.1. Vitamin D Deficiency Weakens Immune Defences against Infection

2.2. Barriers to the Administration of Repeated/Cyclical High Doses of Vitamin D

2.3. Calcitriol or Its Analogues Should Not Be Used as Vitamin D Supplements

2.4. Benefits of Raising Population Vitamin D Sufficiency during a Pandemic

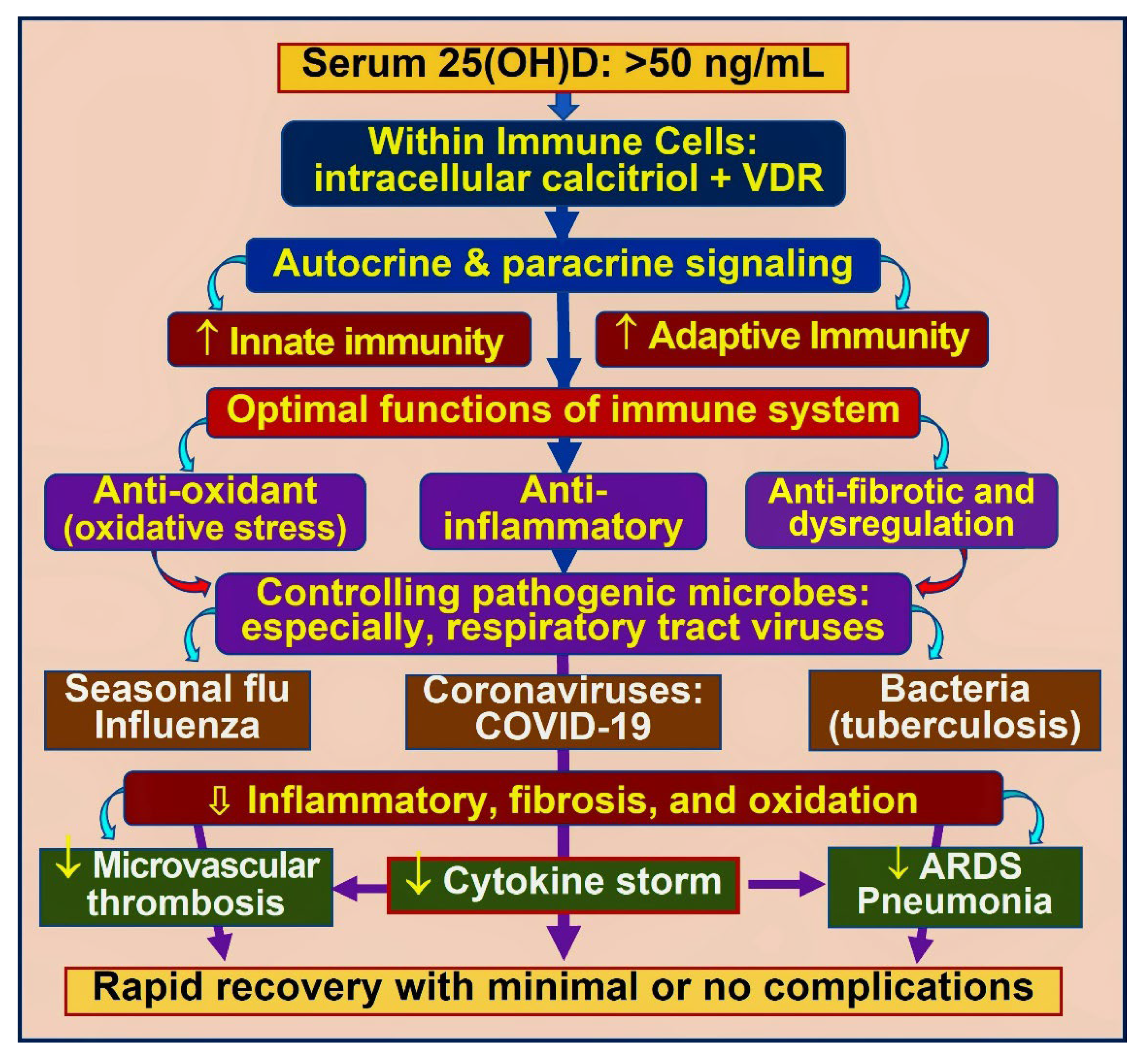

3. Vitamin D and Immune Functions

3.1. Role of Vitamin D in Immune Protection against Infections

3.2. Bioavailable D3 and 25(OH)D for Intracellular Synthesis of Calcitriol in Target Cells

3.3. Autocrine and Paracrine Signalling in Immune Cells

3.4. Improve Vitamin D Status, Reduce the Risk of COVID-19 Complications

4. Summary of Evidence from Clinical Trails

4.1. Potential Adverse Effects of Vitamin D through Hypercalcaemia

4.2. Therapeutic Interventions—Recommendation for High-Dose Vitamin D

4.3. Cost-Effective Strategies to Maintain a Robust Immune System via Vitamin D

4.4. Mechanisms through Which Vitamin D Control Inflammation

4.5. How Obesity Causes Hypovitaminosis D, Requiring Higher Doses of Vitamin D?

5. Doses of Vitamin D Necessary to Boost Serum 25(OH)D

5.1. Vitamin D Intakes Needed to Maintain Serum 25(OH)D Concentrations > 50 ng/mL

5.2. Practical Ways to Use Higher Doses of Vitamin D3 Supplementation

| Serum Vitamin D (ng/mL) ** | Vitamin D Dose: Using 50,000 IU Capsules: Initial and Weekly $ | Duration (Number of Weeks) | Total Amount Needed to Correct Vit. D, Deficiency (IU, in Millions) # | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Bolus Dose (IU) | Follow-Up: $$ The Number of 50,000 IU Caps/Week | |||

| <10 | 300,000 | ×3 | 8 to 10 | 1.5 to 1.8 |

| 11–15 | 200,000 | ×2 | 8 to 10 | 1.0 to 1.2 |

| 16–20 | 200,000 | ×2 | 6 to 8 | 0.8 to 1.0 |

| 21–30 | 100,000 | × 2 | 4 to 6 | 0.5 to 0.7 |

| 31–40 | 100,000 | ×2 | 2 to 4 | 0.3 to 0.5 |

| 41–50 | 100,000 | ×1 | 2 to 4 | 0.2 to 0.3 |

5.3. The Recommended Doses to Maintain Therapeutic Serum 25(OH)D Concentration

| Bodyweight Category | Dose kg/Day (IU) | Dose (IU) (Daily or Weekly) * | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Age) or Using BMI (for age > 18) (kg/Ht. M2) | Average Body Weight (kg) | Daily Dose (IU) | Once a Week (IU) | |

| (Age 1–5) | 5–13 | 70 | 350–900 | 3000–5000 |

| (Age 6–12) | 14–40 | 70 | 1000–2800 | 7000–28,000 |

| (Age 13–18) | 40–50 | 70 | 2800–3500 | 20,000–25,000 |

| BMI ≤ 19 | 50–60 (under-weight adult) | 60 to 80 | 3500–5000 | 25,000–35,000 |

| BMI < 29 | 70–90 (normal: non-obese) | 70 to 90 | 5000–8000 | 35,000–50,000 |

| BMI 30–39 | 90–120 (obese persons) # | 90 to 130 | 8000–15,000 | 50,000–100,000 |

| BMI ≥ 40 $ | 130–170 (morbidly obese) $ | 140 to 180 | 18,000–30,000 | 125,000–200,000 |

5.4. Importance of Parental Vitamin D and 25(OH)D for Generating Calcitriol in Target Cells

5.5. Recommended Calcifediol Doses to Boost Serum 25(OH)D Concentration and Immunity against COVID-19

6. The Rationale for Using Bolus Doses of Vitamin D3 and Calcifediol in Emergencies

There Is No Rationale for Using Calcifediol Analogues

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lips, P.; Jongh, R.T.; Schoor, N.M. Author response for “Trends in vitamin D status around the world”. JBMR Plus 2021, 5, e10414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashman, K.D.; Kiely, M.E.; Andersen, R.; Grønborg, I.M.; Tetens, I.; Tripkovic, L.; Lanham-New, S.A.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Adebayo, F.A.; Gallagher, J.C.; et al. Individual participant data (IPD)-level meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials to estimate the vitamin D dietary requirements in dark-skinned individuals resident at high latitude. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pludowski, P.; Holick, M.F.; Grant, W.B.; Konstantynowicz, J.; Mascarenhas, M.R.; Haq, A.; Povoroznyuk, V.; Balatska, N.; Barbosa, A.P.; Karonova, T.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation guidelines. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 175, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, V.; Vieth, R. Three-year follow-up of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and bone mineral density in nursing home residents who had received 12 months of daily bread fortification with 125 mug of vitamin D(3). Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwaru, J.P.; Zwicker, J.D.; Holick, M.F.; Giovannucci, E.; Veugelers, P.J. The importance of body weight for the dose re-sponse relationship of oral vitamin D supplementation and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D in healthy volunteers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearns, D.M.; Alvarez, J.A.; Tangpricha, V. Large, single-dose, oral vitamin D supplementation in adult populations: A systematic review. Endocr. Pract. 2014, 20, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, L.; Díaz-Muñoz, M.; García-Gaytán, A.C.; Méndez, I. Mechanistic Effects of Calcitriol in Cancer Biology. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5020–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledderose, C.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Junger, W.G. Novel method for real-time monitoring of ATP release reveals multiple phases of autocrine purinergic signalling during immune cell activation. Acta Physiol. 2014, 213, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D regulation of immune function during COVID. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Biology of Vitamin D. J. Steroids Horm. Sci. 2019, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D.D.; Kato, S.; Xie, W.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Schmidt, D.R.; Xiao, R.; Kliewer, S.A. International Union of Pharmacology. LXII. The NR1H and NR1I receptors: Constitutive androstane re-ceptor, pregnene X receptor, farnesoid X receptor alpha, farnesoid X receptor beta, liver X receptor alpha, liver X receptor be-ta, and vitamin D receptor. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 742–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Non-musculoskeletal benefits of vitamin D. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gueli, N.; Verrusio, W.; Linguanti, A.; Di Maio, F.; Martinez, A.; Marigliano, B.; Cacciafesta, M. Vitamin D: Drug of the future. A new therapeutic approach. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 54, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.B.; Al Anouti, F.; Boucher, B.J.; Dursun, E.; Gezen-Ak, D.; Jude, E.B.; Karonova, T.; Pludowski, P. A Narrative Review of the Evidence for Variations in Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentration Thresholds for Optimal Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, S.A.; Bittner, E.A.; Blum, L.; Hutter, M.M.; Camargo, C.A. Association Between Preoperative 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Level and Hospital-Acquired Infections Following Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014, 149, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauss, D.; Freiwald, T.; McGregor, R.; Yan, B.; Wang, L.; Nova-Lamperti, E.; Kumar, D.; Zhang, Z.; Teague, H.; West, E.E.; et al. Autocrine vitamin D signaling switches off pro-inflammatory programs of TH1 cells. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 23, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, S.; Palmini, G.; Aurilia, C.; Falsetti, I.; Miglietta, F.; Iantomasi, T.; Brandi, M.L. Rapid Nontranscriptional Effects of Calcifediol and Calcitriol. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentella, M.C.; Scaldaferri, F.; Pizzoferrato, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Miggiano, G.A.D. Nutrition, IBD and Gut Microbiota: A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Fabián, S.; Bandala, C.; Pichardo-Macías, L.A.; Contreras-García, I.J.; Gómez-Manzo, S.; Hernández-Ochoa, B.; Martínez-Orozco, J.A.; Mejía, I.I.; Cárdenas-Rodríguez, N. Vitamin D and its possible relationship to neuroprotection in COVID-19: Evidence in the literature. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, S.A.; Bittner, E.A.; Blum, L.; McCarthy, C.M.; Bhan, I.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Prospective Study of Vitamin D Status at Initiation of Care in Critically Ill Surgical Patients and Risk of 90-Day Mortality. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.H.; Lee, G.Y.; An, J.H.; Han, S.N. The effects of 1,25(OH)2 D3 treatment on immune responses and intracellular met-abolic pathways of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells from lean and obese mice. IUBMB Life 2021, 74, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Sun, X.; Zheng, S. Correlation between serum 25-(OH)D3 level and immune imbal-ance of Th1/Th2 cytokines in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and its effect on autophagy of human Hashimoto thyroid cells. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaime, J.; Vargas-Bermúdez, D.; Yitbarek, A.; Reyes, J.; Rodríguez-Lecompte, J. Differential immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D (1,25 (OH)2 D3) on the innate immune response in different types of cells infected in vitro with infectious bursal disease virus. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 4265–4277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martineau, A.R.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Hooper, R.L.; Greenberg, L.; Aloia, J.F.; Bergman, P.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Esposito, S.; Ganmaa, D.; Ginde, A.A.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 2017, 356, i6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, L.F.; Nair, K.M.; Kulkarni, B. Sun exposure as a strategy for acquiring vitamin D in developing countries of tropi-cal region: Challenges & way forward. Indian J. Med. Res. 2021, 154, 423–432. [Google Scholar]

- Tomaszewska, A.; Rustecka, A.; Lipińska-Opałka, A.; Piprek, R.P.; Kloc, M.; Kalicki, B.; Kubiak, J.Z. The Role of Vitamin D in COVID-19 and the Impact of Pandemic Restrictions on Vitamin D Blood Content. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 836738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczyk, M.K.; Gaunt, T.R. The effect of circulating zinc, selenium, copper and vitamin K1 on COVID-19 Outcomes: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendehdel, A.; Ansari, M.; Khatami, F.; Mansoursamaei, S.; Dialameh, H. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on the progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3325–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Zhu, X.; Manson, J.E.; Song, Y.; Li, X.; Franke, A.A.; Costello, R.B.; Rosanoff, A.; Nian, H.; Fan, L.; et al. Magnesium status and supplementation influence vitamin D status and metabo-lism: Results from a randomised trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Tang, L.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Liu, M. Populations in low-magnesium areas were associated with higher risk of infection in COVID-19’s early transmission: A nationwide retrospective cohortatudy in the United States. Nutrients 2022, 14, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasa-Irriguible, T.-M.; Bielsa-Berrocal, L.; Bordejé-Laguna, L.; Tural-Llàcher, C.; Barallat, J.; Manresa-Domínguez, J.-M.; Torán-Monserrat, P. Low Levels of Few Micronutrients May Impact COVID-19 Disease Progression: An Observational Study on the First Wave. Metabolites 2021, 11, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaksch, M.; Jorde, R.; Grimnes, G.; Joakimsen, R.; Schirmer, H.; Wilsgaard, T.; Mathiesen, E.B.; Njolstad, I.; Lochen, M.L.; Marz, W.; et al. Vitamin D and mortality: Individual participant data meta-analysis of standardised 25-hydroxyvitamin D in 26916 individuals from a European consortium. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, G.; Hewison, M.; Hopkin, J.; Kenny, R.; Quinton, R.; Rhodes, J.; Subramanian, S.; Thickett, D. Vitamin D and COVID-19: Evidence and recommendations for supplementation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 201912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brożyna, A.A.; Jochymski, C.; Janjetovic, Z.; Jóźwicki, W.; Tuckey, R.C.; Slominski, A.T. CYP24A1 expression inversely corre-lates with melanoma progression: Clinic-pathological studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 19000–19017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Jiang, C.; Cong, L.; Wu, N.; Wang, X.; Hao, M.; Liu, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Cong, X. CYP24A1 inhibition facilitates the an-tiproliferative effect of downregulation of the WNT/beta-Catenin pathway and methylation-mediated regulation of CYP24A1 in colorectal cancer cells. DNA Cell. Biol. 2018, 37, 742–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brustad, N.; Yousef, S.; Stokholm, J.; Bønnelykke, K.; Bisgaard, H.; Chawes, B.L. Safety of high-dose vitamin D supplementa-tion among children aged 0 to 6 years A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2022, 5, e227410. [Google Scholar]

- Amon, U.; Yaguboglu, R.; Ennis, M.; Holick, M.F.; Amon, J. Safety Data in Patients with Autoimmune Diseases during Treatment with High Doses of Vitamin D3 According to the “Coimbra Protocol”. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieth, R. How to optimise vitamin D supplementation to prevent cancer, based on cellular adaptation and hydroxylase en-zymology. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 3675–3684. [Google Scholar]

- Vicchio, D.; Yergey, A.; O’Brien, K.; Allen, L.; Ray, R.; Holick, M. Quantification and kinetics of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 by isotope dilution liquid chromatography/thermospray mass spectrometry. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 1993, 22, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.A.; Cooley, K.; Skidmore, B.; Fritz, H.; Campbell, T.; Seely, D. Vitamin D: Pharmacokinetics and Safety When Used in Conjunction with the Pharmaceutical Drugs Used in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2013, 5, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnick, S.; Abaroa-Salvatierra, A.; Deshmukh, M.; Patel, A. Calcitriol mediated hypercalcaemia with silicone granulomas due to cosmetic injection. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corden, E.; Higgins, E.; Smith, C. Hypercalcaemia-induced kidney injury caused by the vitamin D analogue calcitriol for pso-riasis: A note of caution when prescribing topical treatment. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2016, 41, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-like receptor triggering of a vitamin D-mediated human anti-microbial response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, H.W.; Niles, J.K.; Kroll, M.H.; Bi, C.; Holick, M.F. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circu-lating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, A.A.; Morozov, N.; Daoud, A.; Namir, Y.; Yakir, O.; Shachar, Y.; Lifshitz, M.; Segal, E.; Fisher, L.; Mizrachi, M.; et al. Pre-infection 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels and association with severity of COVID-19 illness. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Global epidemic of coronavirus—COVID-19: What can we do to minimize risks? Eur. J. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 7, 432–438. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, E.S.; Hawrylowicz, C.M. The Impact of Vitamin D on Regulatory T Cells. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010, 11, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.; Tinkov, A.; Strand, T.A.; Alehagen, U.; Skalny, A.; Aaseth, J. Early nutritional interventions with zinc, selenium and vitamin D for raising antiviral resistance against progressive COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaloudi, D.R.; Chourdakis, M. A critical update on the role of mild and serious vitamin D deficiency prevalence and the COVID-19 epidemic in Europe. Nutrition 2021, 93, 111441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, A.R.; Khan, M.; Adeboye, W.; Lee, L.H.H.; Chowdhury, S.I. Ethnicity as a risk factor for vitamin D deficiency and undesirable COVID-19 outcomes. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 32, e2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, G.N.; Locke, E.R.; O’Hare, A.M.; Bohnert, A.S.B.; Boyko, E.J.; Hynes, D.M.; Berry, K. COVID-19 Vaccination Effectiveness Against Infection or Death in a National U.S. Health Care System: A Target Trial Emulation Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regev-Yochay, R.; Gonen, T.; Gilboa, M.; Mandelboim, M.; Indenbaum, V.; Amit, S.; Meltzer, L.; Asraf, K.; Cohen, C.; Fluss, R.; et al. 4th Dose COVID mRNA Vaccines’ Immunogenicity & Efficacy against Omicron VOC. 2022. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.02.15.22270948v1 (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Seneff, S.; Nigh, G.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; McCullough, P.A. Innate immune suppression by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations: The role of G-quadruplexes, exosomes, and MicroRNAs. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 164, 113008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; O’Keefe, J.H. Magnesium and Vitamin D Deficiency as a Potential Cause of Immune Dysfunction, Cyto-kine Storm and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation in COVID-19 patients. Mo. Med. 2021, 118, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanegas-Cedillo, P.E.; Bello-Chavola, O.Y.; Ramirez-Pedraza, N.; Encinas, B.R.; Perez Carrion, C.I.; Jasso-Avila, M.I.; Valladares-Garcia, J.C.; Hernandez-Juarez, D.; Vanegas-Cedillo, P.E.; Vargas-Vazquez, A.; et al. Serum Vitamin D Levels Are Associated With Increased COVID-19 Severity and Mortality Inde-pendent of Whole-Body and Visceral Adiposity. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 813485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar, M.; Bedi, O.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, S.; Jaiswal, G.; Rahi, V.; Yedke, N.G.; Bijalwan, A.; Sharma, S.; et al. Role of vitamins and minerals as immunity boosters in COVID-19. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 1001–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Rathi, H.; Haq, A.; Wimalawansa, S.J.; Sharma, A. Putative roles of vitamin D in modulating immune response and immunopathology associated with COVID-19. Virus Res. 2020, 292, 198235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.H.; Choe, H.J.; Holick, M.F.; Lim, S. Association of vitamin D status with COVID-19 and its severity: Vitamin D and COVID-19: A narrative review. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2022, 23, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnaq, T.; Algethami, F.; Qadhi, A.; Mustafa, R.; Ghafouri, K.; Azhar, W.; Malki, A.A. The impact of vitamin D status on COVID-19 severity among hospitalised patients in the western region of Saudi Arabia: A retrospective cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Mohammadi, V.; Aghababaee, S.A.; Golzarand, M.; Clark, C.C.T.; Babajafari, S. Association of vitamin D status with SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1636–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsche, L.; Glauner, B.; von Mendel, J. COVID-19 Mortality Risk Correlates Inversely with Vitamin D3 Status, and a Mortal-ity Rate Close to Zero Could Theoretically Be Achieved at 50 ng/mL 25(OH)D3: Results of a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Controlling COVID-19 pandemic with cholecalciferol. World J. Adv. Heathc. Res. 2020, 5, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Oral Calcifediol Repletes Blood Vitamin D Concentration within 4 Hours. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/sunilwimalawansa_oral-calcifediol-repletes-blood-vitamin-activity-6803351558714204160-dtnd (accessed on 25 May 2022).

- Bikle, D.D.; Schwartz, J. Vitamin D binding protein, total and free vitamin D levels in different physiological and pathophys-iological conditions. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, J.; Sato, K.; Yumoto, R.; Takano, M. Megalin/Cubilin-mediated Uptake of FITC-labeled IgG by OK Kidney Epithelial Cells. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2011, 26, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashman, K.D.; Ritz, C.; Carlin, A.; Kennedy, M. Vitamin D biomarkers for Dietary Reference Intake development in chil-dren: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.D.; Fitzgerald, A.P.; Viljakainen, H.T.; Jakobsen, J.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Mølgaard, C. Estimation of the dietary requirement for vitamin D in healthy adolescent white girls. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J.; Polonowita, A. Boosting Immunity with Vitamin D for Preventing Complications and Deaths from COVID-19. In COVID 19: Impact, Mitigation, Opportunities and Building Resilience “From Adversity to Serendipity”, Perspectives of Global Relevance Based on Research, Experience and Successes in Combating COVID-19 in Sri Lanka; National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hribar, C.A.; Cobbold, P.H.; Church, F.C. Potential Role of Vitamin D in the Elderly to Resist COVID-19 and to Slow Progression of Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSafar, H.; Grant, W.B.; Hijazi, R.; Uddin, M.; Alkaabi, N.; Tay, G.; Mahboub, B.; Al Anouti, F. COVID-19 Disease Severity and Death in Relation to Vitamin D Status among SARS-CoV-2-Positive UAE Residents. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Lahore, H.; McDonnell, S.L.; Baggerly, C.A.; French, C.B.; Aliano, J.L.; Bhattoa, H.P. Evidence that Vitamin D Supplementation Could Reduce Risk of Influenza and COVID-19 Infections and Deaths. Nutrients 2020, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, B.J. The problems of vitamin d insufficiency in older people. Aging Dis. 2012, 3, 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sabetta, J.R.; DePetrillo, P.; Cipriani, R.J.; Smardin, J.; Burns, L.A.; Landry, M.L. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and the inci-dence of acute viral respiratory tract infections in healthy adults. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, E.J.; Murphy, N. Vitamin D, COVID-19 and Children. Ir. Med. J. 2020, 113, 64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shiravi, A.A.; Saadatkish, M.; Abdollahi, Z.; Miar, P.; Khanahmad, H.; Zeinalian, M. Vitamin D can be effective on the prevention of COVID-19 complications: A narrative review on molecu-lar aspects. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2020, 92, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stohs, S.J.; Aruoma, O.I. Vitamin D and Wellbeing beyond Infections: COVID-19 and Future Pandemics. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2020, 40, 41–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Al-Ani, A.H.; Mitchell, H.; Hendy, P.; Christensen, B. Editorial: Low population mortality from COVID-19 in countries south of latitude 35 degrees North-supports vitamin D as a factor determining severity. Authors’ reply. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 1438–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogues, X.; Ovejero, D.; Pineda-Moncusí, M.; Bouillon, R.; Arenas, D.; Pascual, J.; Ribes, A.; Guerri-Fernandez, R.; Villar-Garcia, J.; Rial, A.; et al. Calcifediol Treatment and COVID-19–Related Outcomes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4017–e4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, M.E.; Costa, L.M.E.; Barrios, J.M.V.; Diaz, J.F.A.; Miranda, J.L.; Bouillon, R.; Gomez, J.M.Q. Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among pa-tients hospitalised for COVID-19: A pilot randomised clinical study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 203, 105751. [Google Scholar]

- Tuncay, M.E.; Gemcioglu, E.; Kayaaslan, B.; Ates, I.; Guner, R.; Eser, F.; Hasanoglu, I.; Kalem, A.K.; Aypak, A.; Agac, Z.S.; et al. A notable key for estimating the severity of COVID-19: 25-hydroxyvitamin D status. Turk. J. Biochem. 2021, 46, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcala-Diaz, J.F.; Limia-Perez, L.; Gomez-Huelgas, R.; Martin-Escalante, M.D.; Cortes-Rodriguez, B.; Zambrana-Garcia, J.L.; Entrenas-Castillo, M.; Perez-Caballero, A.I.; López-Carmona, M.D.; Garcia-Alegria, J.; et al. Calcifediol treatment and hospital mortality due to COVID-19: A cohort study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, S.A.; De Pascale, G.; Needleman, J.S.; Nakazawa, H.; Kaneki, M.; Bajwa, E.K.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Bhan, I. Effect of Cholecalciferol Supplementation on Vitamin D Status and Cathelicidin Levels in Sepsis: A Ran-domised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 43, 1928–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Status: Measurement, Interpretation, and Clinical Application. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Avolio, A.; Avataneo, V.; Manca, A.; Cusato, J.; De Nicolò, A.; Lucchini, R.; Keller, F.; Cantù, M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations Are Lower in Patients with Positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.; Dantas Damascena, A.; Galvão Azevedo, L.M.; de Almeida Oliveira, T.; da Mota Santana, J. Vitamin D deficiency aggravates COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annweiler, G.; Corvaisier, M.; Gautier, J.; Dubée, V.; Legrand, E.; Sacco, G.; Annweiler, C.; on behalf of the GERIA-COVID study group. Vitamin D Supplementation Associated to Better Survival in Hospitalized Frail Elderly COVID-19 Patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-Experimental Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghbooli, Z.; Sahraian, M.A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Pazoki, M.; Kafan, S.; Tabriz, H.M.; Hadadi, A.; Montazeri, M.; Nasiri, M.; Shirvani, A.; et al. Vitamin D sufficiency, a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D at least 30 ng/mL reduced risk for adverse clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vink, M.; Vink-Niese, A. Could Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Be an Effective Treatment for Long COVID and Post COVID-19 Fatigue Syndrome? Lessons from the Qure Study for Q-Fever Fatigue Syndrome. Healthcare 2020, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, I.H.; Fernandes, A.L.; Sales, L.P.; Pinto, A.J.; Goessler, K.F.; Duran, C.S.C.; Silva, C.B.R.; Franco, A.S.; Macedo, M.B.; Dalmolin, M.H.H.; et al. Effect of a single high dose of vitamin D3 on hospital length of stay in patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: A randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, B.J. Why do so many trials of vitamin D supplementation fail? Endocr. Connect. 2020, 9, R195–R206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Significance of plasma PTH-rp in patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy treated with bisphospho-nate. Cancer 1994, 73, 2223–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Li, H.; Wimalawansa, S.J. Cancer-associated hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone-related peptide: A new peptide with diverse roles. Reg. Pept. Lett. 1997, 7, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Azer, S.M.; E Vaughan, L.; Tebben, P.J.; Sas, D.J. 24-Hydroxylase Deficiency Due to CYP24A1 Sequence variants: Compari-son with other vitamin D-mediated hypercalcemia disorders. J. Endocr. Soc. 2021, 5, bvab119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, J.M.; Kuriakose, B.B.; Alhazmi, A.H.; Muthusamy, K. Structural and functional insights on vitamin D receptor and CYP24A1 deleterious single nucleotide pol-ymorphisms: A computational and pharmacogenomics perpetual approach. Cell. Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 874–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, S.L.; Baggerly, C.A.; French, C.B.; Baggerly, L.L.; Garland, C.F.; Gorham, E.D.; Hollis, B.W.; Trump, D.L.; Lappe, J.M. Breast cancer risk markedly lower with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations >/=60 vs. < 20 ng/ml (150 vs. 50 nmol/L): Pooled analysis of two randomised trials and a prospective cohort. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M. High-dose vitamin D therapy: Indications, benefits and hazards. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. Suppl. 1989, 30, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kimball, S.M.; Mirhosseini, N.; Holick, M.F. Evaluation of vitamin D3 intakes up to 15,000 international units/day and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations up to 300 nmol/L on calcium metabolism in a community setting. Dermato-Endocrinology 2017, 9, e1300213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, P.J.; Lehrer, D.S.; Amend, J. Daily oral dosing of vitamin D3 using 5000 TO 50,000 international units a day in long-term hospitalised patients: Insights from a seven year experience. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 189, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieth, R. Vitamin D toxicity, policy, and science. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2007, 22 (Suppl. S2), V64–V68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M.; Endocrine Society. Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorde, R.; Sollid, S.T.; Svartberg, J.; Schirmer, H.; Joakimsen, R.M.; Njølstad, I.; Fuskevåg, O.M.; Figenschau, Y.; Hutchinson, M.Y. Vitamin D 20 000 IU per Week for Five Years Does Not Prevent Progression From Prediabetes to Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Gomez, J.M.; Bouillon, R. Is calcifediol better than cholecalciferol for vitamin D supplementation? Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 1697–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancatella, A.; Cappellani, D.; Vignali, E.; Canale, D.; Marcocci, C. Calcifediol Rather Than Cholecalciferol for a Patient Submitted to Malabsortive Bariatric Surgery: A Case Report. J. Endocr. Soc. 2017, 1, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hurst, S.D.; Muchamuel, T.; Gorman, D.M.; Gilbert, J.M.; Clifford, T.; Kwan, S.; Menon, S.; Seymour, B.; Jackson, C.; Kung, T.T.; et al. New IL-17 family members promote Th1 or Th2 responses in the lung: In vivo function of the novel cyto-kine IL-25. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 443–453. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman, S.; Tan, D.H.; Lambert, M.J.; Scott, N.M.; Judge, M.A.; Hart, P.H. Vitamin D(3) deficiency enhances allergen-induced lymphocyte responses in a mouse model of allergic air-way disease. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2012, 23, 83–87. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, C.; Renner, K.; Peuker, A.; Schoenhammer, G.; Schreiber, L.; Bruss, C.; Eder, R.; Bruns, H.; Flamann, C.; Hoffmann, P.; et al. Physiological levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 induce a suppressive CD4(+) T cell phenotype not reflected in the epigenetic landscape. Scand. J. Immunol. 2022, 95, e13146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Lecompte, J.C.; Yitbarek, A.; Cuperus, T.; Echeverry, H.; van Dijk, A. The immunomodulatory effect of vitamin D in chickens is dose-dependent and influenced by calcium and phosphorus levels. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F. A Network-Based Analysis Reveals the Mechanism Underlying Vitamin D in Suppressing Cytokine Storm and Virus in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 590459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, C.T.; Blackman, A.; Maruri, F.; Rebeiro, P.F.; Huaman, M.; Kator, J.; Algood, H.M.S.; Sterling, T.R. Increased vitamin D receptor expression from macrophages after stimulation with M. tuberculosis among persons who have recovered from extrapulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Release. Available online: http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/ (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Vitamin D Deficiency: Effects on Oxidative Stress, Epigenetics, Gene Regulation, and Aging. Biology 2019, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, P.W. COVID-19, ARDS, ACOVCS, MIS-C, KD, PMIS, TSS, MIS-A: Connecting the Alphabet? Clin. Med. 2020, 2, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onalan, E.; Bozkurt, A.; Gursu, M.F.; Yakar, B.; Donder, E. Role of Betatrophin and Inflammation Markers in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Prediabetes and Metabolic Syndrome. J. Coll. Phys. Surg. Pak. 2022, 32, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatsinki, S.-M.; Elkhwanky, M.-S.; Kummu, O.; Karpale, M.; Buler, M.; Viitala, P.; Rinne, V.; Mutikainen, M.; Tavi, P.; Franko, A.; et al. Fasting-Induced Transcription Factors Repress Vitamin D Bioactivation, a Mechanism for Vitamin D Deficiency in Diabetes. Diabetes 2019, 68, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galassetti, P. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Diabetes. Exp. Diabetes Res. 2012, 2012, 943706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, S. Vitamin D deficiency enhances insulin resistance by promoting inflammation in type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2019, 12, 1859–1867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Askari, G.; Foroughi, M.; Maghsoudi, Z. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on blood sugar and different indices of insulin resistance in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2016, 21, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karonova, T.; Stepanova, A.; Bystrova, A.; Jude, E.B. High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation Improves Microcirculation and Reduces Inflammation in Diabetic Neuropathy Patients. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhwanky, M.; Kummu, O.; Piltonen, T.T.; Laru, J.; Morin-Papunen, L.; Mutikainen, M.; Tavi, P.; Hakkola, J. Obesity Represses CYP2R1, the Vitamin D 25-Hydroxylase, in the Liver and Extrahepatic Tissues. JBMR Plus 2020, 4, e10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roizen, J.D.; Long, C.; Casella, A.; O’Lear, L.; Caplan, I.; Lai, M.; Sasson, I.; Singh, R.; Makowski, A.J.; Simmons, R.; et al. Obesity Decreases Hepatic 25-Hydroxylase Activity Causing Low Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2019, 34, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Fighting against COVID-19: Boosting the immunity with micronutrients, stress reduction, physical activi-ty, and vitamin D. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2020, 3, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Vitamin D and cardiovascular diseases: Causality. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2018, 175, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giusti, A.; Barone, A.; Pioli, G.; Girasole, G.; Razzano, M.; Pizzonia, M.; Pedrazzoni, M.; Palummeri, E.; Bianchi, G. Heterogeneity in serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D response to cholecalciferol in elderly women with secondary hyperparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 1489–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.J.; Gamble, G.D.; Horne, A.M.; Scott, M.A.; Reid, I.R. High-dose oral vitamin D3 supplementation in the elderly. Osteoporos. Int. 2008, 20, 1407–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, E.S.; Pratley, R.E.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Staten, M.A.; Sheehan, P.R.; Lewis, M.R.; Peters, A.; Kim, S.H.; Chatterjee, R.; Aroda, V.R.; et al. Baseline Characteristics of the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study: A Contemporary Prediabetes Cohort That Will Inform Diabetes Prevention Efforts. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1590–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson-Hughes, B.; Staten, M.A.; Knowler, W.C.; Nelson, J.; Vickery, E.M.; LeBlanc, E.S.; Neff, L.M.; Park, J.; Pittas, A.G. Intratrial Exposure to Vitamin D and New-Onset Diabetes Among Adults With Prediabetes: A Secondary Analysis From the Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes (D2d) Study. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 2916–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sabeh, M.; Ghanem, P.; Al-Shaar, L.; Rahme, M.; Baddoura, R.; Halaby, G.; Singh, R.J.; Vanderschueren, D.; Bouillon, R.; El-Hajj Fuleihan, G. Total, Bioavailable, and Free 25(OH)D Relationship with Indices of Bone Health in Elderly: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e990–e1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanth, P.; Chun, R.F.; Hewison, M.; Adams, J.S.; Bouillon, R.; Vanderschueren, D.; Lane, N.; Cawthon, P.M.; Dam, T.; Barrett-Connor, E.; et al. Associations of total and free 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D with serum markers of inflammation in older men. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 2291–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.; Bouillon, R.; Thadhani, R.; Schoenmakers, I. Vitamin D metabolites in captivity? Should we measure free or total 25(OH)D to assess vitamin D status? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 173, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.B.; Gallagher, J.C.; Jorde, R.; Berg, V.; Walsh, J.; Eastell, R.; Evans, A.L.; Bowles, S.; Naylor, K.E.; Jones, K.S.; et al. Determination of Free 25(OH)D Concentrations and Their Relationships to Total 25(OH)D in Multiple Clinical Populations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3278–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginde, A.; Brower, R.G.; Caterino, J.M.; Finck, L.; Banner-Goodspeed, V.M.; Grissom, C.K.; Hayden, D.; Hough, C.L.; Hyzy, R.C.; et al.; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network Early High-Dose Vitamin D3 for Critically Ill, Vitamin D-Deficient Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 2529–2540. [Google Scholar]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Vitamin D: Everything You Need to Know; Karunaratne & Sons: Homagama, Sri Lanka, 2012; ISBN 978-955-9098-94-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Clinical Perspective: Effective and practical ways to overcome vitamin D deficiency. Fam. Med. Community Health 2021, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasnezhad, A.; Amani, R.; Hajiani, E.; Alavinejad, P.; Cheraghian, B.; Ghadiri, A. Effect of Vitamin D on Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Health-Related Quality of Life in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 28, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, R.; Salli, A.; Cingoz, H.T.; Kucuksen, S.; Ugurlu, H. Efficacy of vitamin D replacement therapy on patients with chronic nonspecific widespread musculoskeletal pain with vitamin D deficiency. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 19, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysostomou, S.; Information, R. Vitamin D Daily short-term Supplementation does not Affect Glycemic Outcomes of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2016, 86, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, H.; Amani, R.; Feizi, A.; Askari, G.; Kohan, S.; Tavasoli, P. Vitamin D Supplementation for Premenstrual Syndrome-Related Inflammation and Antioxidant Markers in Students with Vitamin D Deficient: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdizadehkashi, A.; Rokhgireh, S.; Tahermanesh, K.; Eslahi, N.; Minaeian, S.; Samimi, M. The effect of vitamin D supple-mentation on clinical symptoms and metabolic profiles in patients with endometriosis. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2021, 37, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Saghazade, A.R.; Abbaszadeh-Mashkani, S.; Banafshe, H.R.; Ghoreishi, F.S.; Mesdaghinia, A.; Ghaderi, A. The effect of vitamin D supplementation on tobacco-related disorders in individuals with a tobacco use disorder: A randomized clinical trial. J. Addict. Dis. 2022, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, G.; Hewison, M.; Hopkin, J.; Kenny, R.A.; Quinton, R.; Rhodes, J.; Subramanian, S.; Thickett, D. Preventing vitamin D deficiency during the COVID-19 pandemic: UK definitions of vitamin D sufficiency and recommended supplement dose are set too low. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, e48–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.; Schloss, J.; Brown, D.; Celis, D.; Finnell, J.; Hedo, R.; Honcharov, V.; Pantuso, T.; Peña, H.; Lauche, R.; et al. The effects of vitamin D on acute viral respiratory infections: A rapid review. Adv. Integr. Med. 2020, 7, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, P.; Blaser, A.R.; Berger, M.M.; Alhazzani, W.; Calder, P.C.; Casaer, M.P.; Hiesmayr, M.; Mayer, K.; Montejo, J.C.; Pichard, C.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 48–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D in Health and Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, R.; Liu, P.T.; Modlin, R.L.; Adams, J.S.; Hewison, M. Impact of vitamin D on immune function: Lessons learned from genome-wide analysis. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygun, H. Vitamin D can prevent COVID-19 infection-induced multiple organ damage. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 2020, 393, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, E.L.; Ismailova, A.; Dimeloe, S.K.; Hewison, M.; White, J.H. Vitamin D and Immune Regulation: Antibacterial, Antiviral, Anti-Inflammatory. JBMR Plus 2020, 5, e10405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, L.E.; Burke, F.; Mura, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qureshi, O.S.; Hewison, M.; Walker, L.S.K.; Lammas, D.A.; Raza, K.; Sansom, D.M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and IL-2 combine to inhibit T cell production of inflammatory cytokines and promote development of regulatory T cells expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 5458–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bania, A.; Pitsikakis, K.; Mavrovounis, G.; Mermiri, M.; Beltsios, E.T.; Adamou, A.; Konstantaki, V.; Makris, D.; Tsolaki, V.; Gourgoulianis, K.; et al. Therapeutic Vitamin D Supplementation Following COVID-19 Diagnosis: Where Do We Stand?—A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Ecclesiis, O.; Gavioli, C.; Martinoli, C.; Raimondi, S.; Chiocca, S.; Miccolo, C.; Bossi, P.; Cortinovis, D.; Chiaradonna, F.; Palorini, R.; et al. Vitamin D and SARS-CoV2 infection, severity and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268396-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sune Negre, J.M.; Azpitarte, I.O.; Barrios, P.d.A.; Hernández Herrero, G. Calcifediol Soft Capsules. SP Patent WO 2016/124724, 11 August 2016. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2016124724A1 (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Petkovich, M.; Melnick, J.; White, J.; Tabash, S.; Strugnell, S.; Bishop, C.W. Modified-release oral calcifediol corrects vitamin D insufficiency with minimal CYP24A1 upregulation. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 148, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varikasuvu, S.R.; Thangappazham, B.; Vykunta, A.; Duggina, P.; Manne, M.; Raj, H.; Aloori, S. COVID-19 and vitamin D (Co-VIVID study): A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2022, 20, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J.M.; Subramanian, S.; Laird, E.; Griffin, G.; Kenny, R.A. Perspective: Vitamin D Deficiency and COVID-19 Severity—Plausibly Linked by Latitude, Ethnicity, Impacts on Cytokines, ACE2, and Thrombosis (R1). J. Intern. Med. 2020, 289, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Sri Lanka. J. Diabetes Endocrinol. Metabol. 2012, 1, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Achieving population vitamin D sufficiency will markedly reduce healthcare costs. EJBPS 2020, 7, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

| Weight (lbs) | Weight (kg) | Calcifediol ~ (mg) # | If Calcifediol Is Not Available: Bolus/Loading Dose of Vitamin D3 ## |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8–14 | 4–6 | 0.05 | 20,000 |

| 15–21 | 7–10 | 0.1 | 40,000 |

| 22–30 | 10–14 | 0.15 | 60,000 |

| 31–40 | 15–18 | 0.2 | 80,000 |

| 41–50 | 19–23 | 0.3 | 100,000 |

| 51–60 | 24–27 | 0.4 | 150,000 |

| 61–70 | 28–32 | 0.5 | 200,000 |

| 71–85 | 33–39 | 0.6 | 240,000 |

| 86–100 | 40–45 | 0.7 | 280,000 |

| 101–150 | 46–68 | 0.8 | 320,000 |

| 151–200 | 69–90 | 1.0 | 400,000 |

| 201–300 | 91–136 | 1.5 | 600,000 |

| >300 | >137 | 2.0 | 800,000 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wimalawansa, S.J. Rapidly Increasing Serum 25(OH)D Boosts the Immune System, against Infections—Sepsis and COVID-19. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142997

Wimalawansa SJ. Rapidly Increasing Serum 25(OH)D Boosts the Immune System, against Infections—Sepsis and COVID-19. Nutrients. 2022; 14(14):2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142997

Chicago/Turabian StyleWimalawansa, Sunil J. 2022. "Rapidly Increasing Serum 25(OH)D Boosts the Immune System, against Infections—Sepsis and COVID-19" Nutrients 14, no. 14: 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142997

APA StyleWimalawansa, S. J. (2022). Rapidly Increasing Serum 25(OH)D Boosts the Immune System, against Infections—Sepsis and COVID-19. Nutrients, 14(14), 2997. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142997