The Relationship between Angiogenic Factors and Energy Metabolism in Preeclampsia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Etiopathogenesis of Preeclampsia: Current State

1.2. Antiangiogenic Factors as Biomarkers in Preeclampsia

1.3. Purpose of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Placental Lipid Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Maternal, Obstetric and Perinatal Outcomes

3.2. Serum and Placental Analysis

3.2.1. Lipids and Carbohydrates in Maternal Plasma

3.2.2. Antiangiogenic Factors in Maternal Plasma

3.2.3. Placental Lipid Metabolism

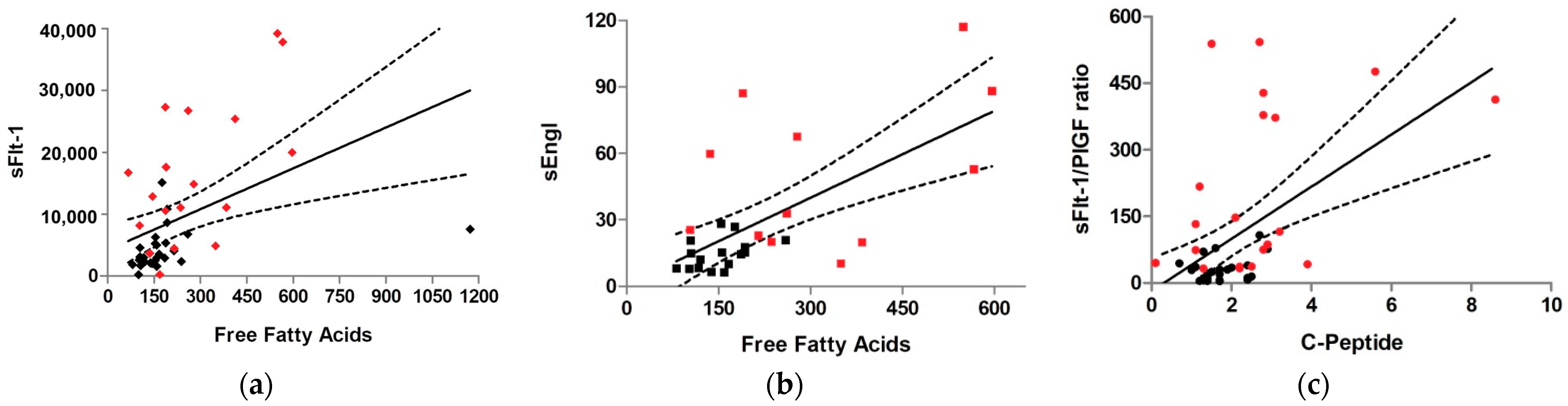

3.3. Correlation of Maternal and Placental Metabolism with Antiangiogenic Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Interpretation of Results

4.2.1. Relationship between Insulin Resistance and Preeclampsia

4.2.2. Relationship between Lipid Metabolism and Preeclampsia

4.3. Strengths of the Study

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIP | Atherogenic index of plasma |

| Akt1 | Serine/threonine kinase 1 |

| ANS | Autonomic nervous system |

| ART | Assisted reproductive technology |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CRI-II | Castelli risk index II |

| CRR | Cardiac risk ratio |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EOPE | Early-onset preeclampsia |

| FAE | Fatty acid esterification |

| FAO | Fatty acid oxidation |

| FBG | Fasting basal glucose |

| FFA | Free fatty acids |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HELLP | Hemolysis, elevated liver function and low platelets |

| HOMA-IR | Homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LCHAD | Long-chain 3-hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LOPE | Late-onset preeclampsia |

| LPL | Lipoprotein lipase |

| LXRs | Liver X receptors |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| OGTT | Oral glucose challenge test |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PlGF | Placental growth factor |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| sEGFR | Soluble epidermal growth factor receptor |

| sEng | Soluble endoglin |

| sFlt-1 | Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 |

| TFP | Mitochondrial trifunctional protein |

| TG/Prot ratio | Triglyceride/protein ratio |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming growth factor β1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VEGFR-1 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor -1 |

References

- Brown, M.A.; Magee, L.A.; Kenny, L.C.; Karumanchi, S.A.; McCarthy, F.P.; Saito, S.; Hall, D.R.; Warren, C.E.; Adoyi, G.; Ishaku, S. The hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: ISSHP classification, diagnosis & management recommendations for international practice. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018, 13, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poon, L.C.; Shennan, A.; Hyett, J.A.; Kapur, A.; Hadar, E.; Divakar, H.; McAuliffe, F.; da Silva Costa, F.; von Dadelszen, P.; McIntyre, H.D.; et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on pre-eclampsia: A pragmatic guide for first-trimester screening and prevention. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2019, 145 (Suppl. 1), 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, G.J.; Redman, C.W.; Roberts, J.M.; Moffett, A. Pre-eclampsia: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. BMJ 2019, 366, l2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phipps, E.A.; Thadhani, R.; Benzing, T.; Karumanchi, S.A. Pre-eclampsia: Pathogenesis, novel diagnostics and therapies. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, C.W. Current topic: Pre-eclampsia and the placenta. Placenta 1991, 12, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soobryan, N.; Murugesan, S.; Pandiyan, A.; Moodley, J.; Mackraj, I. Angiogenic Dysregulation in Pregnancy-Related Hypertension—A Role for Metformin. Reprod. Sci. 2018, 25, 1531–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, O.P.; Murugesan, S.; Moodley, J.; Mackraj, I. Differential expression of miRNAs are associated with the insulin signaling pathway in preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2018, 40, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, M.B.; Ferreira, R.C.; Moura, F.A.; Bueno, N.B.; de Oliveira, A.C.M.; Goulart, M.O.F. Cross-Talk between Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Preeclampsia. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8238727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrazzi, E.; Stampalija, T.; Aupont, J.E. The evidence for late-onset pre-eclampsia as a maternogenic disease of pregnancy. Fetal Matern. Med. Rev. 2013, 24, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robillard, P.Y.; Dekker, G.; Scioscia, M.; Bonsante, F.; Iacobelli, S.; Boukerrou, M.; Hulsey, T.C. Increased BMI has a linear association with lateonset preeclampsia: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223888. [Google Scholar]

- Gallos, I.D.; Sivakumar, K.; Kilby, M.D.; Coomarasamy, A.; Thangaratinam, S.; Vatish, M. Pre-eclampsia is associated with, and preceded by, hypertriglyceridaemia: A meta-analysis. BJOG 2013, 120, 1321–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, J.G.; Diamond, P.; Singh, G.; Bell, C.M. Brief overview of maternal triglycerides as a risk factor for pre-eclampsia. BJOG 2006, 113, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staff, A.C. The two-stage placental model of preeclampsia: An update. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2019, 134–135, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spradley, F.T. Metabolic abnormalities and obesity’s impact on the risk for developing preeclampsia. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2017, 312, R5–R12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.B.; Zheng, J. Regulation of placental angiogenesis. Microcirculation 2014, 21, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.N. Cytokines, angiogenic, and antiangiogenic factors and bioactive lipids in preeclampsia. Nutrition 2015, 31, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leanos-Miranda, A.; Navarro-Romero, C.S.; Sillas-Pardo, L.J.; Ramirez-Valenzuela, K.L.; Isordia-Salas, I.; Jimenez-Trejo, L.M. Soluble Endoglin As a Marker for Preeclampsia, Its Severity, and the Occurrence of Adverse Outcomes. Hypertension 2019, 74, 991–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, R.J.; Lam, C.; Qian, C.; Yu, K.F.; Maynard, S.E.; Sachs, B.P.; Sibai, B.M.; Epstein, F.H.; Romero, R.; Thadhani, R.; et al. Soluble endoglin and other circulating antiangiogenic factors in preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karumanchi, S.A. Angiogenic Factors in Preeclampsia: From Diagnosis to Therapy. Hypertension 2016, 67, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oujo, B.; Perez-Barriocanal, F.; Bernabeu, C.; Lopez-Novoa, J.M. Membrane and soluble forms of endoglin in preeclampsia. Curr. Mol. Med. 2013, 13, 1345–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesha, S.; Toporsian, M.; Lam, C.; Hanai, J.; Mammoto, T.; Kim, Y.M.; Bdolah, Y.; Lim, K.H.; Yuan, H.T.; Libermann, T.A.; et al. Soluble endoglin contributes to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; Akolekar, R.; Syngelaki, A.; Poon, L.C.; Nicolaides, K.H. A competing risks model in early screening for preeclampsia. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2012, 32, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeisler, H.; Llurba, E.; Chantraine, F.; Vatish, M.; Staff, A.C.; Sennstrom, M.; Olovsson, M.; Brennecke, S.P.; Stepan, H.; Allegranza, D. Predictive Value of the sFlt-1:PlGF Ratio in Women with Suspected Preeclampsia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verlohren, S.; Herraiz, I.; Lapaire, O.; Schlembach, D.; Zeisler, H.; Calda, P.; Sabria, J.; Markfeld-Erol, F.; Galindo, A.; Schoofs, K.; et al. New gestational phase-specific cutoff values for the use of the soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1/placental growth factor ratio as a diagnostic test for preeclampsia. Hypertension 2014, 63, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, J.L.; Visiedo, F.; Fernandez-Deudero, A.; Bugatto, F.; Perdomo, G. Decreased mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in placentas from women with preeclampsia. Placenta 2012, 33, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdomo, G.; Commerford, S.R.; Richard, A.M.; Adams, S.H.; Corkey, B.E.; O’Doherty, R.M.; Brown, N.F. Increased beta-oxidation in muscle cells enhances insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism and protects against fatty acid-induced insulin resistance despite intramyocellular lipid accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 27177–27186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visiedo, F.; Bugatto, F.; Sanchez, V.; Cozar-Castellano, I.; Bartha, J.L.; Perdomo, G. High glucose levels reduce fatty acid oxidation and increase triglyceride accumulation in human placenta. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 305, E205–E212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abascal-Saiz, A.; Fuente-Luelmo, E.; Haro, M.; de la Calle, M.; Ramos-Alvarez, M.P.; Perdomo, G.; Bartha, J.L. Placental Compartmentalization of Lipid Metabolism: Implications for Singleton and Twin Pregnancies. Reprod. Sci. 2020, 28, 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.F.; Stefanovic-Racic, M.; Sipula, I.J.; Perdomo, G. The mammalian target of rapamycin regulates lipid metabolism in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2007, 56, 1500–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdomo, G.; Kim, D.H.; Zhang, T.; Qu, S.; Thomas, E.A.; Toledo, F.G.; Slusher, S.; Fan, Y.; Kelley, D.E.; Dong, H.H. A role of apolipoprotein D in triglyceride metabolism. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 1298–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobakht, M.G.B.F. Application of metabolomics to preeclampsia diagnosis. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2018, 64, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Xi, X.; Cui, F.; Wen, M.; Hong, A.; Hu, Z.; Ni, J. Abnormal expression and clinical significance of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and sFlt-1 in patients with preeclampsia. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 4673–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raio, L.; Bersinger, N.A.; Malek, A.; Schneider, H.; Messerli, F.H.; Hürter, H.; Rimoldi, S.F.; Baumann, M.U. Ultra-high sensitive C-reactive protein during normal pregnancy and in preeclampsia: A pilot study. J. Hypertens. 2019, 37, 1012–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsukasa, H.; Masuyama, H.; Takamoto, N.; Hiramatsu, Y. Circulating leptin and angiogenic factors in preeclampsia patients. Endocr. J. 2008, 55, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Shu, C.; Liu, Z.; Tong, W.; Cui, M.; Wei, C.; Tang, J.J.; Liu, X.; Hai, H.; Jiang, J.; et al. Serum protein marker panel for predicting preeclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018, 14, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valensise, H.; Larciprete, G.; Vasapollo, B.; Novelli, G.P.; Menghini, S.; di Pierro, G.; Arduini, D. C-peptide and insulin levels at 24–30 weeks’ gestation: An increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2002, 103, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhi, I.; Hogan, J.W.; Canick, J.; Sosa, M.B.; Carpenter, M.W. Midpregnancy serum C-peptide concentration and subsequent pregnancy-induced hypertension. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kaaja, R.; Laivuori, H.; Laakso, M.; Tikkanen, M.J.; Ylikorkala, O. Evidence of a state of increased insulin resistance in preeclampsia. Metab. Clin. Exp. 1999, 48, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yogev, Y.; Chen, R.; Hod, M.; Coustan, D.R.; Oats, J.J.N.; Metzger, B.E.; Lowe, L.P.; Dyer, A.R.; Trimble, E.; McCance, D. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study: Preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 255. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.; Freestone, N.S.; Anim-Nyame, N.; Arrigoni, F.I.F. Microvascular function in pre-eclampsia is influenced by insulin resistance and an imbalance of angiogenic mediators. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalano, P.M.; Tyzbir, E.D.; Wolfe, R.R.; Calles, J.; Roman, N.M.; Amini, S.B.; Sims, E.A. Carbohydrate metabolism during pregnancy in control subjects and women with gestational diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. 1993, 264 Pt 1, E60–E67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnick, L.M. Ionic basis of hypertension, insulin resistance, vascular disease, and related disorders. The mechanism of ”syndrome X“. Am. J. Hypertens. 1993, 6, 123S–134S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P. Pregnancy complicating diabetes. Am. J. Med. 1949, 7, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioscia, M.; Karumanchi, S.A.; Goldman-Wohl, D.; Robillard, P.Y. Endothelial dysfunction and metabolic syndrome in preeclampsia: An alternative viewpoint. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2015, 108, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Liu, G.; Guo, G. Association of insulin resistance and autonomic tone in patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2018, 40, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, R.L.M.; Callo, G.; Horta, B.L. C-peptide and cardiovascular mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysisPeptido C y mortalidad cardiovascular: Revision sistematica y metanalisis. Rev. Panam. Salud. Publica 2019, 43, e23. [Google Scholar]

- Lteif, A.A.; Han, K.; Mather, K.J. Obesity, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome: Determinants of endothelial dysfunction in whites and blacks. Circulation 2005, 112, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Taveira, T.H.; Choudhary, G.; Whitlatch, H.; Wu, W.C. Fasting serum C-peptide levels predict cardiovascular and overall death in nondiabetic adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012, 1, e003152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, J.L.; Gonzalez-Bugatto, F.; Fernandez-Macias, R.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, N.L.; Comino-Delgado, R.; Hervias-Vivancos, B. Metabolic syndrome in normal and complicated pregnancies. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008, 137, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawyer, C.; Afroze, S.H.; Drever, N.; Allen, S.; Jones, R.; Zawieja, D.C.; Kuehl, T.; Uddin, M.N. Attenuation of hyperglycemia-induced apoptotic signaling and anti-angiogenic milieu in cultured cytotrophoblast cells. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2016, 35, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; He, B.; Cheng, W. Associations of lipid levels during gestation with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus: A prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e013509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavan-Gautam, P.; Rani, A.; Freeman, D.J. Distribution of Fatty Acids and Lipids During Pregnancy. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2018, 84, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Plows, J.F.; Stanley, J.L.; Baker, P.N.; Reynolds, C.M.; Vickers, M.H. The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, A.; Bertolotto, A.; Resi, V.; Volpe, L.; Di Cianni, G. Triglyceride metabolism in pregnancy. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2011, 55, 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Alahakoon, T.I.; Medbury, H.J.; Williams, H.; Lee, V.W. Lipid profiling in maternal and fetal circulations in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction-a prospective case control observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, A.C.; Dechend, R.; Pijnenborg, R. Learning from the placenta: Acute atherosis and vascular remodeling in preeclampsia-novel aspects for atherosclerosis and future cardiovascular health. Hypertension 2010, 56, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojcik-Baszko, D.; Charkiewicz, K.; Laudanski, P. Role of dyslipidemia in preeclampsia—A review of lipidomic analysis of blood, placenta, syncytiotrophoblast microvesicles and umbilical cord artery from women with preeclampsia. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2018, 139, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaire, A.A.; Thakar, S.R.; Wagh, G.N.; Joshi, S.R. Placental lipid metabolism in preeclampsia. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belalcazar, S.; Acosta, E.J.; Murillo, M.; Jairo, J.; Salcedo Cifuentes, M. Conventional biomarkers for cardiovascular risks and their correlation with the castelli risk index-indices and TG/HDL-c. Arch. Med. 2020, 20, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.; Pathak, M.S.; Paul, A. A Study on Atherogenic Indices of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension Patients as Compared to Normal Pregnant Women. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, BC05–BC08. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauri, M.; Calmarza, P.; Ibarretxe, D. Dyslipemias and pregnancy, an update. Clin. Investig. Arterioscler. 2021, 33, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tateishi, A.; Ohira, S.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kanno, H. Histopathological findings of pregnancy-induced hypertension: Histopathology of early-onset type reflects two-stage disorder theory. Virchows Arch. 2018, 472, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mifsud, W.; Sebire, N.J. Placental pathology in early-onset and late-onset fetal growth restriction. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 2014, 36, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endresen, M.J.; Lorentzen, B.; Henriksen, T. Increased lipolytic activity and high ratio of free fatty acids to albumin in sera from women with preeclampsia leads to triglyceride accumulation in cultured endothelial cells. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1992, 167, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, L.; Hermouet, A.; Tsatsaris, V.; Therond, P.; Sawamura, T.; Evain-Brion, D.; Fournier, T. Lipids from oxidized low-density lipoprotein modulate human trophoblast invasion: Involvement of nuclear liver X receptors. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 4583–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry-Berger, J.; Mouzat, K.; Baron, S.; Bernabeu, C.; Marceau, G.; Saru, J.P.; Sapin, V.; Lobaccaro, J.-M.A.; Caira, F. Endoglin (CD105) expression is regulated by the liver X receptor alpha (NR1H3) in human trophoblast cell line JAR. Biol. Reprod. 2008, 78, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Han, T.L.; Chen, H.; Baker, P.N.; Qi, H.; Zhang, H. Impaired mitochondrial fusion, autophagy, biogenesis and dysregulated lipid metabolism is associated with preeclampsia. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 359, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.H.; Eather, S.R.; Freeman, D.J.; Meyer, B.J.; Mitchell, T.W. A Lipidomic Analysis of Placenta in Preeclampsia: Evidence for Lipid Storage. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemse, N.; Sundrani, D.; Kale, A.; Joshi, S. Maternal Micronutrients, Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Gene Expression of Angiogenic and Inflammatory Markers in Pregnancy Induced Hypertension Rats. Arch. Med. Res. 2017, 48, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biale, Y. Lipolytic activity in the placentas of chronically deprived fetuses. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 1985, 64, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procopciuc, L.M.; Stamatian, F.; Caracostea, G. LPL Ser447Ter and Asn291Ser variants in Romanians: Associations with preeclampsia—Implications on lipid profile and prognosis. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2014, 33, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.J.; Williamson, R.A.; Chen, K.; Smith, J.L.; Murray, J.C.; Merrill, D.C. Lipoprotein lipase gene mutations and the genetic susceptibility of preeclampsia. Hypertension 2001, 38, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Barrett, H.L.; Kubala, M.H.; Scholz Romero, K.; Denny, K.J.; Woodruff, T.M.; McIntyre, H.D.; Callaway, L.K.; Nitert, M.D. Placental lipase expression in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia: A case-control study. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2015, 13, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviram, A.; Giltvedt, M.K.; Sherman, C.; Kingdom, J.; Zaltz, A.; Barrett, J.; Melamed, N. The role of placental malperfusion in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia in dichorionic twin and singleton pregnancies. Placenta 2018, 70, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantanahom, N.; Phupong, V. Clinical risk factors for preeclampsia in twin pregnancies. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.Q.; Sun, M.N.; Yang, Z. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase lowers fatty acid oxidation in preeclampsia-like mice at early gestational stage. Chin. Med. J. 2011, 124, 3141–3147. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Yang, Z.; Han, Y.; Yu, H. Correlation of long-chain fatty acid oxidation with oxidative stress and inflammation in pre-eclampsia-like mouse models. Placenta 2015, 36, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control n = 30 | Preeclampsia n = 26 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATERNAL RESULTS | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 36.1 ± 4.3 | 34.5 ± 5.1 | 0.219 |

| Ethnic Group: | 0.592 | ||

| 18 (60.0%) | 14 (58.3%) | |

| 6 (20.0%) | 8 (33.3%) | |

| 0 | 1 (4.1%) | |

| Pregravid body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.1 ± 2.7 | 23.8 ± 3.7 | 0.516 |

| Body mass index classification: | |||

| 0 | 1 (3.8%) | 0.276 |

| 19 (63.3%) | 12 (46.1%) | 0.052 |

| 3 (10.0%) | 6 (23.0%) | 0.166 |

| 0 | 1 (3.8%) | 0.276 |

| Gestational weight gain (kg) | 13.5 (9.00) | 13.0 (6.00) | 0.844 |

| OBSTETRIC RESULTS | |||

| Gestational age at study (weeks) | 39.0 (2.0) | 35.0 (5.0) | 5.4 × 10−8 * |

| Parity: | |||

| 6 (22.2%) | 13 (52.0%) | 0.032 * |

| 4 (14.8%) | 5 (20.0%) | 0.546 |

| 14 (51.8%) | 5 (20.0%) | 0.068 |

| 10 (37.0%) | 7 (28.0%) | 0.203 |

| Mode of pregnancy: | 0.578 | ||

| 19 (63.3%) | 18 (69.2%) | |

| 1 (10%) | 0 | |

| 5 (16.6%) | 5 (19.2%) | |

| Twin pregnancy | 4 (13.3%) | 6 (23.1%) | 0.342 |

| Obstetric reason for caesarean section: | |||

| A.-Fetal: | |||

| 10 (35.7%) | 2 (8.0%) | 0.016 * |

| 1 (3.5%) | 0 | |

| 0 | 2 (8.0%) | |

| B.-Maternal: | |||

| 0 | 17 (68.0%) | 1 × 10−6 * |

| 13 (46.4%) | 0 | 8.8 × 10−5 * |

| 2 (7.1%) | 0 | |

| 0 | 3 (12.0%) | |

| 1 (3.5%) | 0 | |

| 1 (3.5%) | 0 | |

| 0 | 1 (4.0%) | |

| PERINATAL RESULTS | |||

| EFW (g) | 3081.4 ± 578.9 | 1794.1 ± 712.0 | 7.007 × 10−9 * |

| Centile EFW | 55.5 ± 32.4 | 34.4 ± 37.9 | 0.040 * |

| Fetal growth restriction: | |||

| 1 (4.2%) | 3 (10.7%) | 0.299 |

| 0 | 11 (39.3%) | 2.16 × 10−4 * |

| Neonatal birth weight (g) | 3232.1 ± 461.5 | 2092.6 ± 829.4 | 1.036 × 10−7 * |

| Neonatal birth centile weight | 58.5 ± 26.7 | 37.9 ± 39.0 | 0.023 * |

| Neonatal sex: | 0.868 | ||

| 12 (37.5%) | 11 (35.4%) | |

| 20 (62.5%) | 20 (64.5%) | |

| Umbilical artery pH at birth | 7.30 ± 0.06 | 7.28 ± 0.07 | 0.176 |

| Placental weight | 581.68 ± 130.85 | 403.37 ± 150.73 | 4.7 × 10−5 * |

| Comparison Control vs. Preeclampsia | Comparison Subsets of Preeclampsia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n = 30 | Preeclampsia n = 26 | p Value | EOPE n = 11 | LOPE n = 15 | p Value | |

| TC (mg/dL) | 257.0 ± 45.5 | 264.6 ± 41.0 | 0.532 | 264.4 ± 46.2 | 264.7 ± 38.7 | 0.986 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 149.6 ± 45.5 | 146.6 ± 55.3 | 0.835 | 117.4 ± 63.9 | 165.4 ± 41.3 | 0.040 * |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 71.7 ± 16.2 | 76.3 ± 26.1 | 0.463 | 95.2 ± 24.1 | 64.2 ± 19.7 | 0.003 * |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 257.1 ± 118.0 | 295.4 ± 117.9 | 0.258 | 219.1 ± 64.5 | 344.4 ± 119.7 | 0.009 * |

| FFA (mg/dL) | 157.0 (75.0) | 225.5 (202.0) | 0.005 * | 242.1 (226.0) | 215.0 (157.0) | 0.663 |

| Cardiac risk ratio † | 3.383 (2.2) | 3.551 (1.4) | 0.884 | 2.6 (1.1) | 4.5 (2.2) | 0.007 * |

| Castelli risk index II † | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 0.899 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 0.003 * |

| TG/HDL ratio | 3.0 (2.7) | 3.4 (5.2) | 0.540 | 2.0 (1.4) | 5.4 (5.7) | 0.002 * |

| AIP † | 0.17 ± 0.21 | 0.22 ± 0.28 | 0.444 | 0.001 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.001 * |

| FBG (mg/dL) | 74.3 ± 4.9 | 74.1 ± 15.6 | 0.970 | 80.2 ± 17.8 | 69.8 ± 12.7 | 0.107 |

| FINS (pmol/L) | 10.5 (6.0) | 13.0 (15.0) | 0.197 | 11.0 (22.0) | 14.0 (15.0) | 0.918 |

| C-peptide (ng(mL) | 1.7 (0.8) | 2.4 (1.4) | 0.021 * | 2.0 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.3) | 0.973 |

| HOMA-IR † | 2.0 (1.3) | 2.3 (3.0) | 0.393 | 2.4 (2.6) | 2.3 (2.9) | 0.785 |

| sFlt-1 (pg/mL) | 4045.5 (3850.0) | 16,223.0 (19,549.0) | 4 × 10−5 * | 20,911.0 (18,504.0) | 11,060.0 (15,539.0) | 0.123 |

| PlGF (pg/mL) | 244.5 (352.4) | 87.4 (84.1) | 1 × 10−4 * | 50.3 (54.3) | 116.1 (102.5) | 0.041 * |

| sFlt-1 /PlGF ratio | 22.9 (30.2) | 140.0 (363.3) | 1.46 × 10−7 * | 428.5 (644.1) | 86.7 (174.9) | 0.008 |

| sEng (ng/mL) | 11.6 (10.5) | 42.9 (45.6) | 2 × 10−4 * | 56.7 (71.2) | 32.8 (47.5) | 0.827 |

| Comparison Control vs. Preeclampsia | Comparison Subsets of Preeclampsia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n = 30 | Preeclampsia n = 26 | p Value | EOPE n = 11 | LOPE n = 15 | p Value | |

| Fatty Acid Oxidation (nmol/g) | 3.827 (1.100) | 4.374 (1.300) | 0.322 | 4.373 (1.630) | 4.409 (1.02) | 0.758 |

| Fatty Acid Esterification (nmol/g) | 1.084 ± 1.124 | 1.370 ± 0.703 | 0.305 | 1.601 ± 0.755 | 1.157 ± 0.605 | 0.134 |

| Triglyceride Content (mg/dL) | 266.249 ± 255.726 | 245.660 ± 204.248 | 0.762 | 342.532 ± 217.175 | 156.860 ± 150.236 | 0.026 * |

| Triglyceride/Protein Ratio | 762.279 ± 746.581 | 693.887 ± 673.828 | 0.744 | 984.714 ± 768.637 | 427.296 ± 457.036 | 0.045 * |

| Angiogenic Factors in Maternal Plasma | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sFlt-1 | PlGF | sFlt-1/PlGF Ratio | sEngl | |||||

| METABOLISM IN MATERNAL PLASMA | rs | p | rs | p | rs | p | rs | p |

| Cholesterol | 0.112 | 0.438 | −0.142 | 0.325 | 0.126 | 0.383 | 0.082 | 0.651 |

| LDL-c | −0.040 | 0.789 | 0.028 | 0.849 | −0.066 | 0.654 | -0.182 | 0.318 |

| HDL-c | 0.002 | 0.988 | −0.193 | 0.189 | 0.074 | 0.619 | 0.076 | 0.680 |

| Triglycerides | 0.383 | 0.007 * | 0.092 | 0.533 | 0.191 | 0.192 | 0.405 | 0.022 * |

| FFA | 0.575 | 4.5 × 10−5 * | −0.080 | 0.606 | 0.509 | 4.13 × 10−4 * | 0.522 | 0.004 * |

| FBS | −0.092 | 0.525 | −0.179 | 0.214 | 0.021 | 0.883 | -0.259 | 0.153 |

| FINS | 0.077 | 0.605 | −0.207 | 0.162 | 0.167 | 0.263 | 0.215 | 0.245 |

| C-peptide | 0.348 | 0.017 * | −0.233 | 0.115 | 0.394 | 0.006 * | 0.466 | 0.008 * |

| HOMA-IR † | 0.026 | 0.860 | −0.218 | 0.141 | 0.121 | 0.416 | 0.172 | 0.355 |

| PLACENTAL LIPID METABOLISM | ||||||||

| Fatty acid oxidation | 0.168 | 0.271 | −0.187 | 0.218 | 0.219 | 0.148 | 0.166 | 0.391 |

| Fatty acid esterification | 0.193 | 0.203 | −0.058 | 0.707 | 0.092 | 0.549 | v0.095 | 0.626 |

| Triglyceride content | −0.014 | 0.925 | −0.071 | 0.645 | −0.018 | 0.909 | −0.256 | 0.180 |

| TG/Protein ratio | −0.027 | 0.860 | −0.089 | 0.561 | −0.019 | 0.902 | −0.257 | 0.178 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abascal-Saiz, A.; Duque-Alcorta, M.; Fioravantti, V.; Antolín, E.; Fuente-Luelmo, E.; Haro, M.; Ramos-Álvarez, M.P.; Perdomo, G.; Bartha, J.L. The Relationship between Angiogenic Factors and Energy Metabolism in Preeclampsia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102172

Abascal-Saiz A, Duque-Alcorta M, Fioravantti V, Antolín E, Fuente-Luelmo E, Haro M, Ramos-Álvarez MP, Perdomo G, Bartha JL. The Relationship between Angiogenic Factors and Energy Metabolism in Preeclampsia. Nutrients. 2022; 14(10):2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102172

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbascal-Saiz, Alejandra, Marta Duque-Alcorta, Victoria Fioravantti, Eugenia Antolín, Eva Fuente-Luelmo, María Haro, María P. Ramos-Álvarez, Germán Perdomo, and José L. Bartha. 2022. "The Relationship between Angiogenic Factors and Energy Metabolism in Preeclampsia" Nutrients 14, no. 10: 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102172

APA StyleAbascal-Saiz, A., Duque-Alcorta, M., Fioravantti, V., Antolín, E., Fuente-Luelmo, E., Haro, M., Ramos-Álvarez, M. P., Perdomo, G., & Bartha, J. L. (2022). The Relationship between Angiogenic Factors and Energy Metabolism in Preeclampsia. Nutrients, 14(10), 2172. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102172