Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on COVID-19 Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Assessment

2.4. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

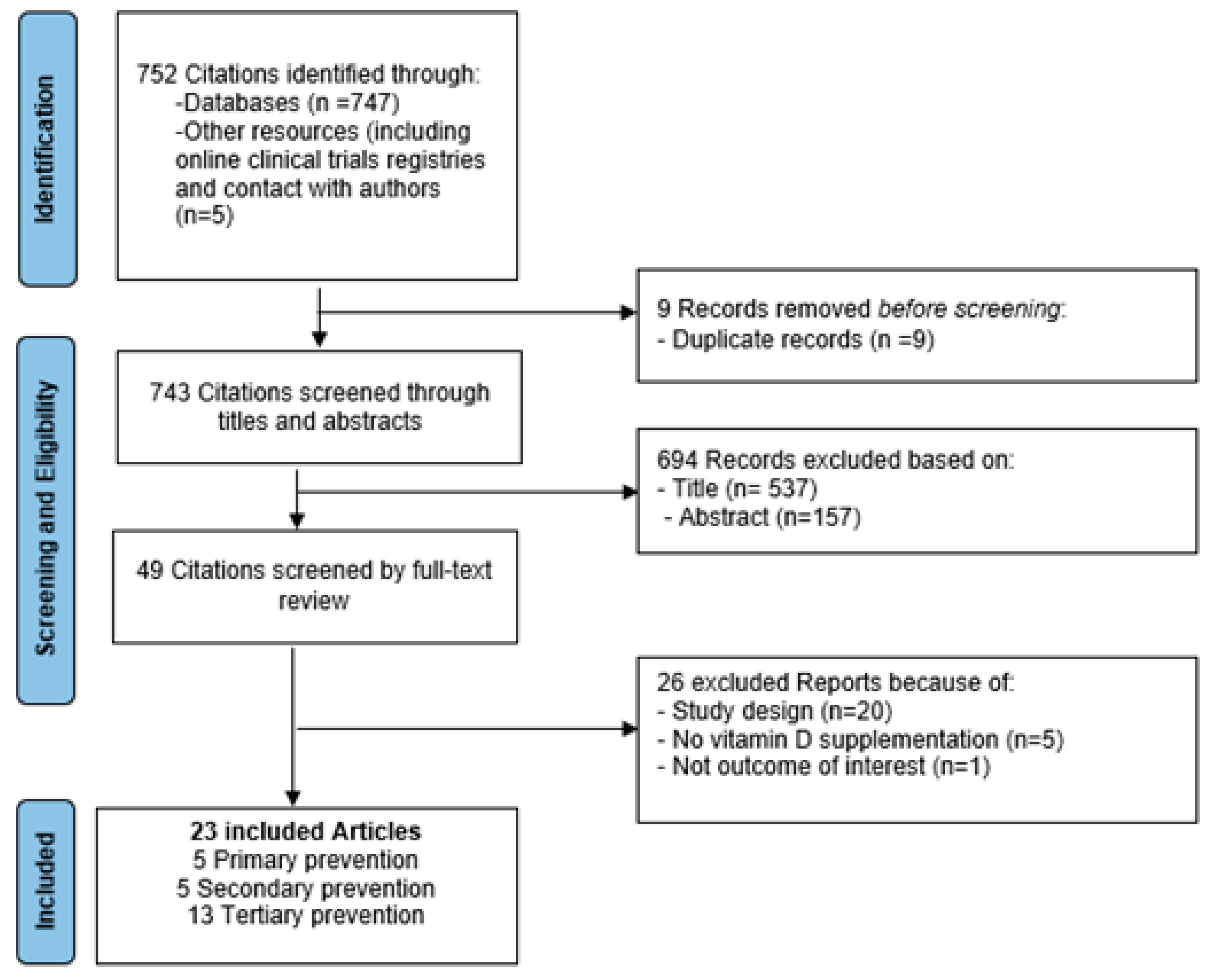

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias

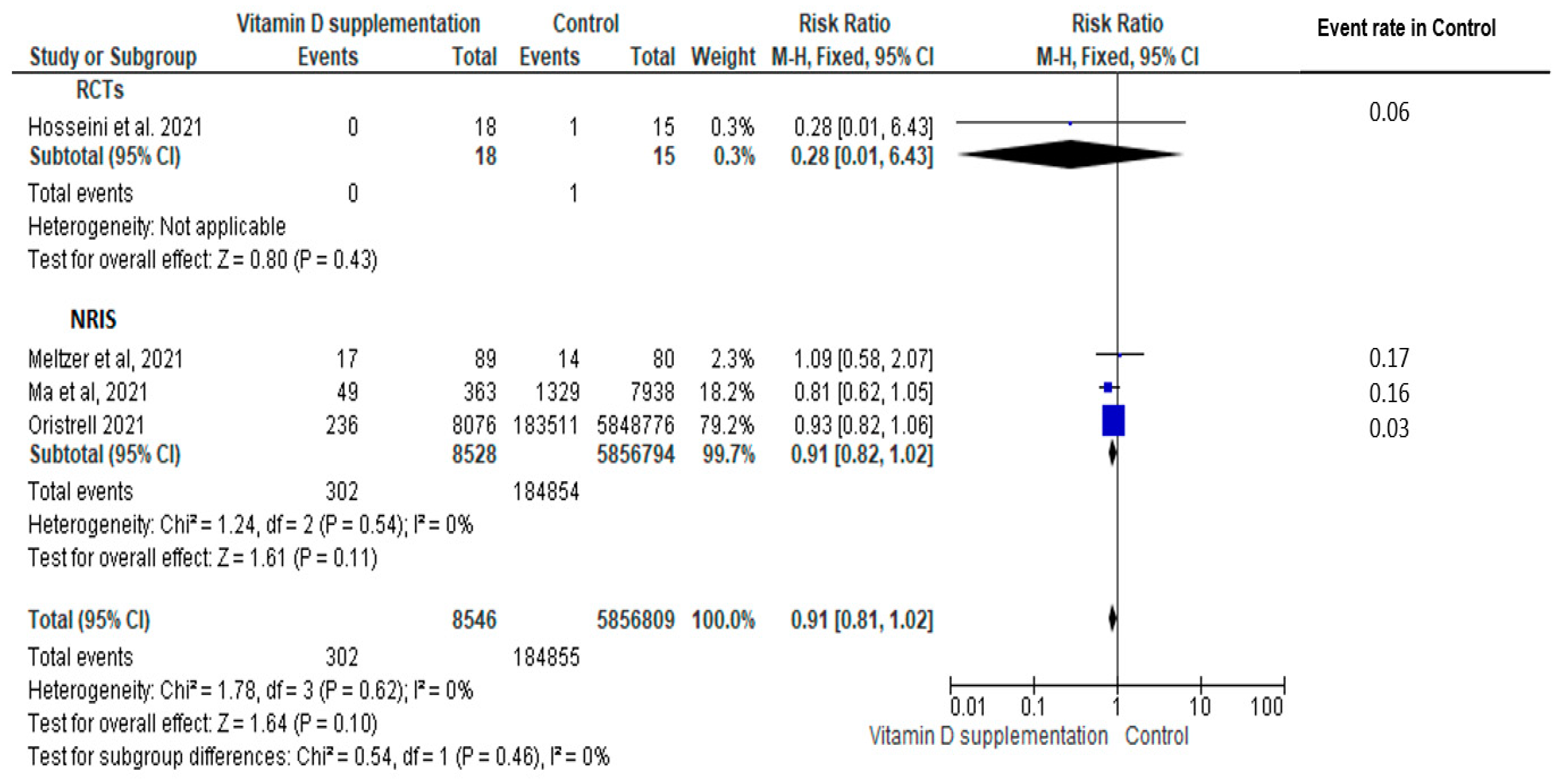

3.4. Primary Prevention

3.5. Secondary Prevention

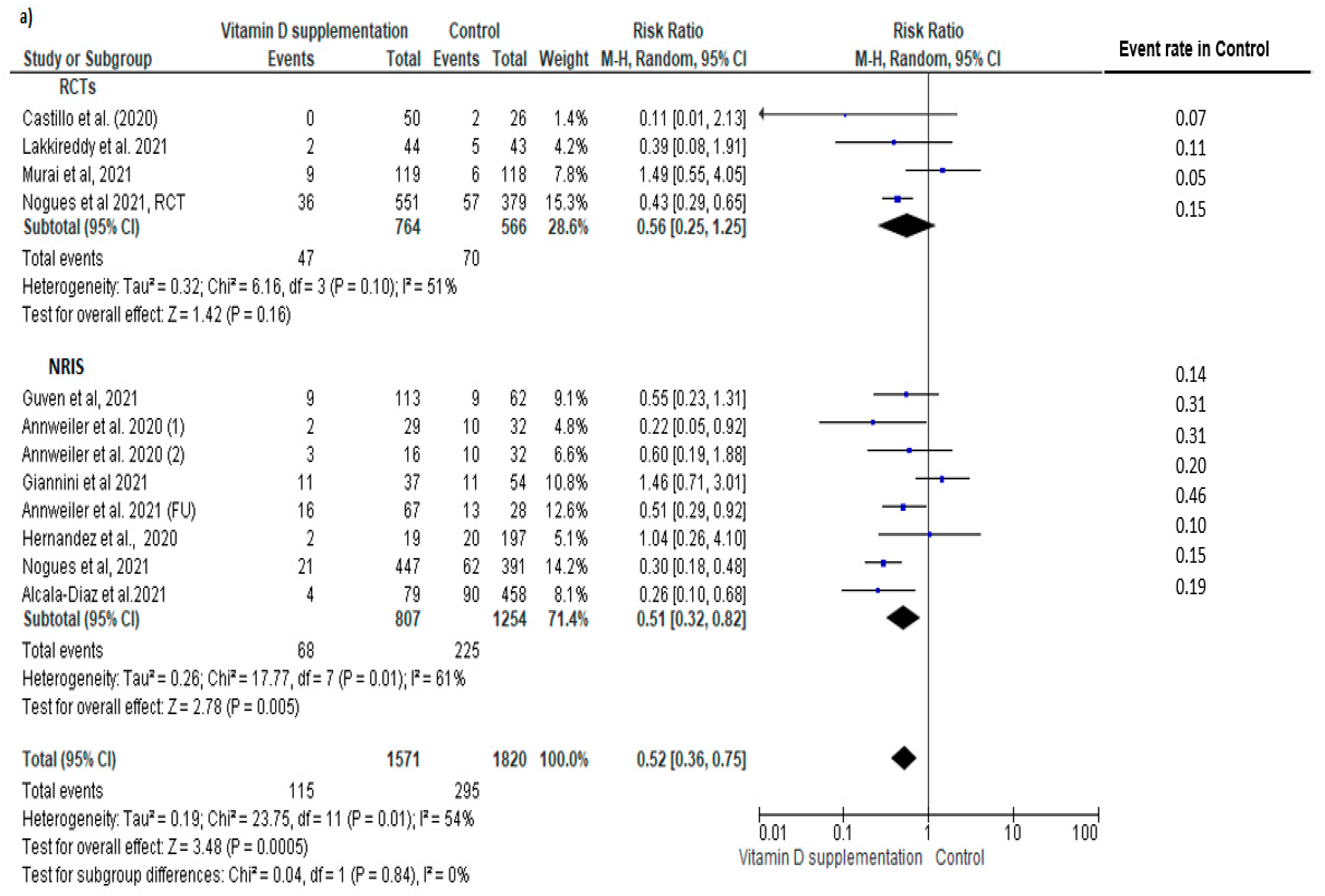

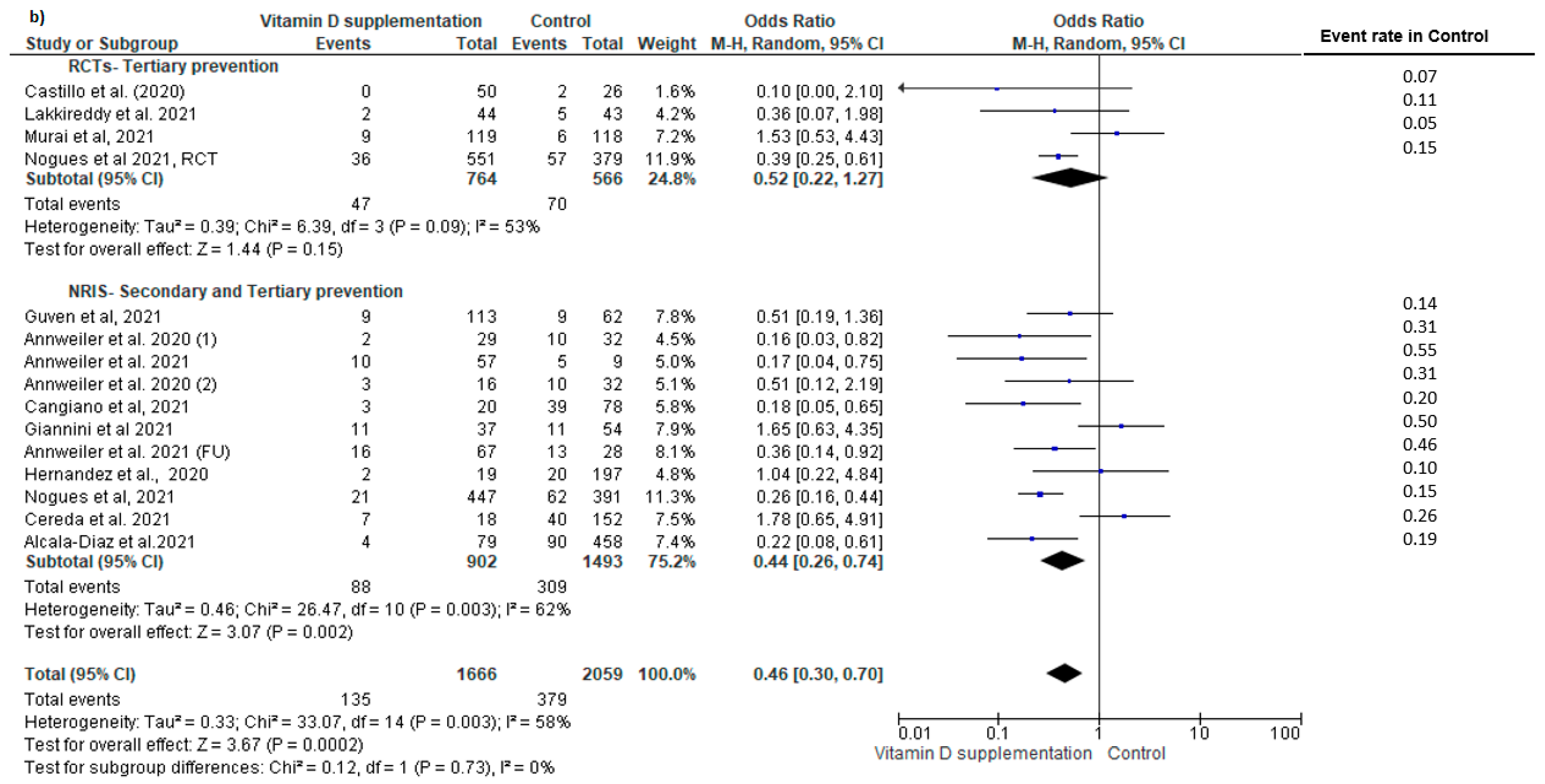

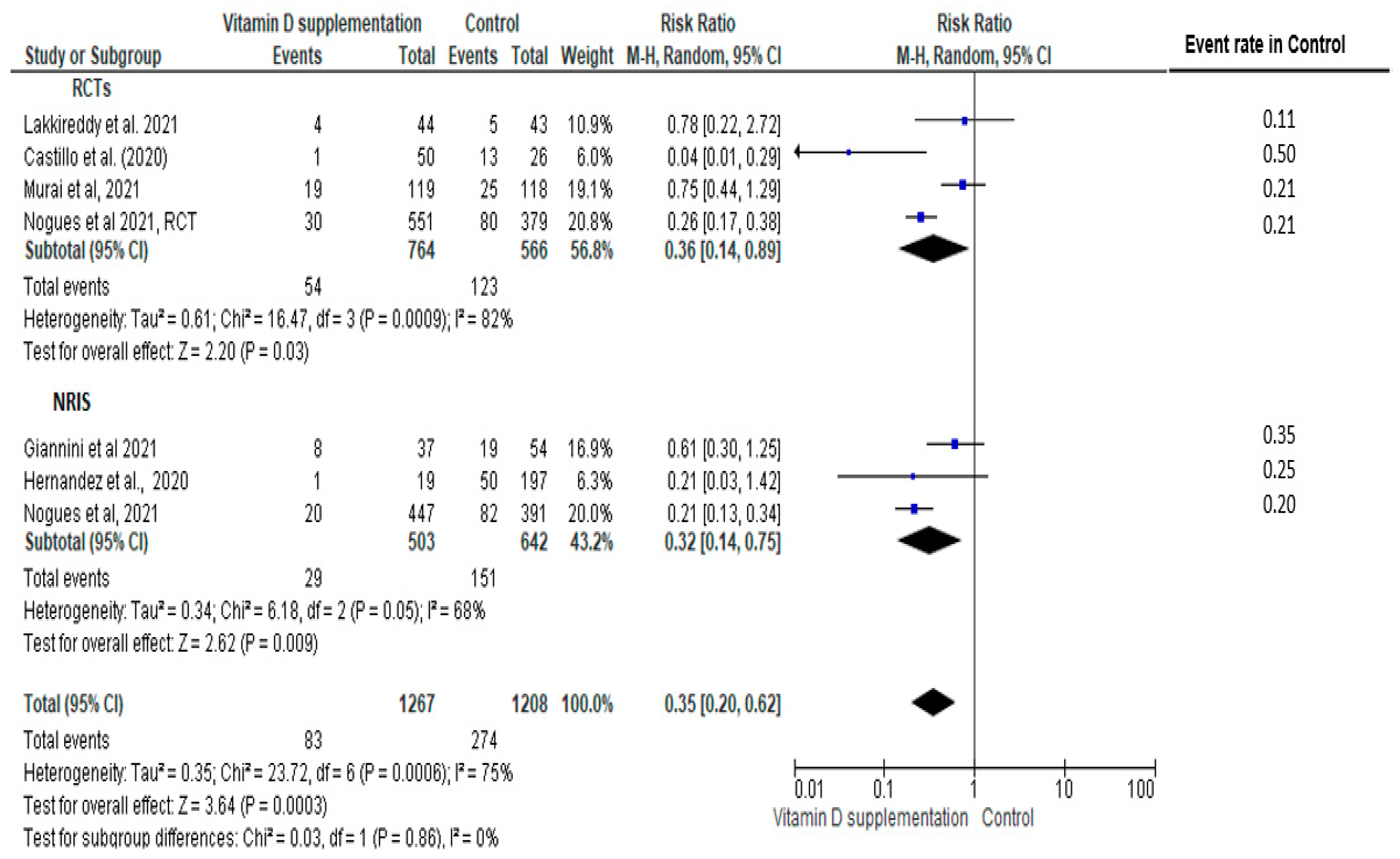

3.6. Tertiary Prevention

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Worldometer. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Jolliffe, D.A.; Camargo, C.A.; Sluyter, J.D.; Aglipay, M.; Aloia, J.F.; Ganmaa, D.; Bergman, P.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Borzutzky, A.; Damsgaard, C.T.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate data from randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, M.E.; Costa, L.M.E.; Barrios, J.M.V.; Díaz, J.F.A.; Miranda, J.L.; Bouillon, R.; Gomez, J.M.Q. Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 203, 105751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annweiler, C.; Hanotte, B.; de L’Eprevier, C.G.; Sabatier, J.-M.; Lafaie, L.; Célarier, T. Vitamin D and survival in COVID-19 patients: A quasi-experimental study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 204, 105771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annweiler, G.; Corvaisier, M.; Gautier, J.; Dubée, V.; Legrand, E.; Sacco, G.; Annweiler, C. Vitamin D Supplementation Associated to Better Survival in Hospitalized Frail Elderly COVID-19 Patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-Experimental Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcala-Diaz, J.; Limia-Perez, L.; Gomez-Huelgas, R.; Martin-Escalante, M.; Cortes-Rodriguez, B.; Zambrana-Garcia, J.; Entrenas-Castillo, M.; Perez-Caballero, A.; López-Carmona, M.; Garcia-Alegria, J.; et al. Calcifediol Treatment and Hospital Mortality Due to COVID-19: A Cohort Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.F.; Broad, E.; Murphy, R.; Pappachan, J.M.; Pardesi-Newton, S.; Kong, M.F.; Jude, E.B. High-Dose Cholecalciferol Booster Therapy is Associated with a Reduced Risk of Mortality in Patients with COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Observational Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Bhansali, A.; Khare, N.; Suri, V.; Yaddanapudi, N.; Sachdeva, N.; Puri, G.D.; Malhotra, P. Short term, high-dose vitamin D supplementation for COVID-19 disease: A randomised, placebo-controlled, study (SHADE study). Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 98, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabico, S.; Enani, M.A.; Sheshah, E.; Aljohani, N.J.; Aldisi, D.A.; Alotaibi, N.H.; Alshingetti, N.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alnaami, A.M.; Amer, O.E.; et al. Effects of a 2-Week 5000 IU versus 1000 IU Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Recovery of Symptoms in Patients with Mild to Moderate Covid-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zuno, G.A.; González-Estevez, G.; Matuz-Flores, M.G.; Macedo-Ojeda, G.; Hernández-Bello, J.; Mora-Mora, J.C.; Pérez-Guerrero, E.E.; García-Chagollán, M.; Vega-Magaña, N.; Turrubiates-Hernández, F.J.; et al. Vitamin D Levels in COVID-19 Outpatients from Western Mexico: Clinical Correlation and Effect of Its Supplementation. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulateef, D.S.; Rahman, H.S.; Salih, J.M.; Osman, S.M.; Mahmood, T.A.; Omer, S.H.S.; Ahmed, R.A. COVID-19 severity in relation to sociodemographics and vitamin D use. Open Med. 2021, 16, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, I.H.; Fernandes, A.L.; Sales, L.P.; Pinto, A.J.; Goessler, K.F.; Duran, C.S.; Silva, C.B.; Franco, A.S.; Macedo, M.B.; Dalmolin, H.H.; et al. Effect of a Single High Dose of Vitamin D3 on Hospital Length of Stay in Patients with Moderate to Severe COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakkireddy, M.; Gadiga, S.G.; Malathi, R.D.; Karra, M.L.; Raju, I.S.S.V.; Chinapaka, S.; Baba, K.S.S.; Kandakatla, M. Impact of daily high dose oral vitamin D therapy on the inflammatory markers in patients with COVID 19 disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oristrell, J.; Oliva, J.C.; Subirana, I.; Casado, E.; Domínguez, D.; Toloba, A.; Aguilera, P.; Esplugues, J.; Fafián, P.; Grau, M. Association of Calcitriol Supplementation with Reduced COVID-19 Mortality in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Population-Based Study. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereda, E.; Bogliolo, L.; Lobascio, F.; Barichella, M.; Zecchinelli, A.L.; Pezzoli, G.; Caccialanza, R. Vitamin D supplementation and outcomes in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients from the outbreak area of Lombardy, Italy. Nutrition 2020, 82, 111055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Dantas Damascena, A.; Galvão Azevedo, L.M.; de Almeida Oliveira, T.; da Mota Santana, J. Vitamin D deficiency aggravates COVID-19: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Banerjee, M.; Bhadada, S.K.; Shetty, A.J.; Singh, B.; Vyas, A. Vitamin D supplementation and clinical outcomes in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 45, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, B.C.; Deeks, J.J.; Higgins, J.P.; Shea, B. Chapter 24: Including non-randomized studies on intervention effects. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 62; Cochrane: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.S.J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 62; Cochrane: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Quality Criteria Checklist: Primary Research in Evidence Analysis Manual: Steps in the Academy Evidence Analysis Process. 2012. Available online: http://andevidencelibrary.com/files/Docs/2012_Jan_EA_Manual.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Handu, D. Comparison of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics updated Quality Criteria Checklist and Cochrane’s ROB 2.0 as risk of bias tools. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Cochrane Library: London, UK, 2018; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Deeks, J.J.H.J.; Altman, D.G. Chapter 10: Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 62; Cochrane: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.H.J.; Sterne, J.A.C. Chapter 13: Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 62; Cochrane: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nogués, X.; Diana, O.; Quesada-Gomez, J.M.; Bouillon, R.; Arenas, D.; Pascual, J.; Villar-Garcia, J.; Rial, A.; García-Giralt, N. Calcifediol Treatment and COVID-19-Related Outcomes. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3771318 (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Caballero-García, A.; Pérez-Valdecantos, D.; Guallar, P.; Caballero-Castillo, A.; Roche, E.; Noriega, D.C.; Córdova, A. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Muscle Status in Old Patients Recovering from COVID-19 Infection. Medicina 2021, 57, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, B.; Tremblay, C.; Longo, C.; Golchi, S.; White, J.; Quach, C. Prevention of COVID-19 with Oral Vitamin D Supplemental Therapy in Essential healthCare Teams (PROTECT): Ancillary Study of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04483635 (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- Annweiler, C.; Beaudenon, M.; Simon, R.; Guenet, M.; Otekpo, M.; Célarier, T.; Gautier, J. Vitamin D supplementation prior to or during COVID-19 associated with better 3-month survival in geriatric patients: Extension phase of the GERIA-COVID study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2021, 213, 105958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, M.; Gültekin, H. The effect of high-dose parenteral vitamin D3 on COVID-19-related inhospital mortality in critical COVID-19 patients during intensive care unit admission: An observational cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangiano, B.; Fatti, L.M.; Danesi, L.; Gazzano, G.; Croci, M.; Vitale, G.; Gilardini, L.; Bonadonna, S.; Chiodini, I.; Caparello, C.F.; et al. Mortality in an Italian nursing home during COVID-19 pandemic: Correlation with gender, age, ADL, vitamin D supplementation, and limitations of the diagnostic tests. Aging 2020, 12, 24522–24534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Zhou, T.; Heianza, Y.; Qi, L. Habitual use of vitamin D supplements and risk of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: A prospective study in UK Biobank. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 1275–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, D.O.; Best, T.J.; Zhang, H.; Vokes, T.; Arora, V.; Solway, J. Association of Vitamin D Status and Other Clinical Characteristics With COVID-19 Test Results. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogues, X.; Ovejero, D.; Pineda-Moncusí, M.; Bouillon, R.; Arenas, D.; Pascual, J.; Ribes, A.; Guerri-Fernandez, R.; Villar-Garcia, J.; Rial, A.; et al. Calcifediol treatment and COVID-19-related outcomes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e4017–e4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, J.L.; Nan, D.; Fernandez-Ayala, M.; García-Unzueta, M.; Hernández-Hernández, M.A.; López-Hoyos, M.; Muñoz-Cacho, P.; Olmos, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Cuadra, M.; Ruiz-Cubillán, J.J.; et al. Vitamin D Status in Hospitalized Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e1343–e1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, S.; Passeri, G.; Tripepi, G.; Sella, S.; Fusaro, M.; Arcidiacono, G.; Torres, M.; Michielin, A.; Prandini, T.; Baffa, V.; et al. Effectiveness of In-Hospital Cholecalciferol Use on Clinical Outcomes in Comorbid COVID-19 Patients: A Hypothesis-Generating Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler-Laporte, G.; Nakanishi, T.; Mooser, V.; Morrison, D.R.; Abdullah, T.; Adeleye, O.; Mamlouk, N.; Kimchi, N.; Afrasiabi, Z.; Rezk, N.; et al. Vitamin D and COVID-19 susceptibility and severity in the COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Saxena, D.; Mavalankar, D. Vitamin D supplementation, COVID-19 and disease severity: A meta-analysis. QJM Int. J. Med. 2021, 114, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikniaz, L.; Akbarzadeh, M.A.; Hosseinifard, H.; Hosseini, M.-S. The impact of vitamin D supplementation on mortality rate and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv 2021, 2, S1–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, D.; Roy, A.; Maitra, S.; Shankar, V.; Khanna, P.; Baidya, D.K. “Vitamin D supplementation and COVID-19 treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 102189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Wan, Z.; Han, S.-F.; Li, B.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Qin, L.-Q. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on the level of circulating high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients 2014, 6, 2206–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Reference | Design, Setting | Participants | Duration of Intervention | Treatment Arms | Baseline Serum 25OHD (nmol/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D | Control | |||||

| Primary Prevention | ||||||

| Hosseini et al. [27], 2021 | RCT, Canada | Unvaccinated healthcare workers (25–58 years old, male: 5.9%) | 4–10 weeks | Intervention: vitamin D: bolus 100,000 IU + 10,000 IU/week (n = 19); Control: placebo (n = 15) | 49.56 ± 26.64 | 48.02 ± 15.16 |

| Abdulateef et al. [11], 2021 | Retrospective cohort, Iraq | Patients with COVID-19 (15–80 years old, male: 44.4%) | Not specified | Intervention: regularly supplemented with vitamin D prior to COVID-19 exposure (n = 127), “ranging from <1000 IU/day to >4000 IU/day for <1 week to >2 weeks”; Control: no vitamin D supplements (n = 300) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ma et al. [31], 2021 | Prospective cohort, United Kingdom | Adults who have records of COVID-19 test results from UK Biobank (37–73 years old, male: 44.4%) | Not specified | Intervention: regularly supplemented with vitamin D (not specified) prior to COVID-19 exposure (n = 363); Control: no vitamin D supplements (n = 7934) | 56 ± 20.8 | 47 ± 21.1 |

| Meltzer et al. [32], 2020 | Retrospective cohort, United States | 489 patients with data for a vitamin D level within 1 year before COVID-19 testing (49.2 ± 18.4 years old, male: 25.0%) | Not specified | Intervention: “regularly supplemented with vitamin D over the past year excluding the 14 days before testing: (≤1000 IU, 2000 IU, ≥3000 IU)” (n = 277); Control: no vitamin D supplements (n = 212) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Oristrell et al. [14], 2021 | Retrospective cohort, Spain | Patients with chronic kidney disease (70.2 ± 15.6 years old, male: 42.5%) | 10 months | Intervention: supplemented with vitamin D prior to COVID-19 exposure (10,596 IU/day) from 1 April 2019 to 28 February 2020 (n = 8076); Control: no vitamin D supplements (n = 5,848,776) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Secondary Prevention | ||||||

| Rastogi et al. [8], 2020 | RCT, India | Asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic cases of COVID-19 (36 to 51 years old, male: 45.0%) | 7 days or more if needed | Intervention: vitamin D: 60,000 IU/day; (n = 16) (with therapeutic target 25 OHD > 125 nmol/day); Control: identical placebo (n = 24) | 21.5 (17.7, 32.7) | 23.8 (20.5, 31.2) |

| Sánchez-Zuno et al. [10], 2021 | RCT, Mexico | COVID-19 outpatients 20–74 years old, male: 47.7%) | 14 days | Intervention: 10,000 IU of vitamin D3/day (n = 22); Control: placebo (n = 20) | 50.5 (30.5, 114.7) | 58.5 (30.25, 114) |

| Annweiler et al. [4], 2021 | Quasi-experimental with retrospective collection of data, France | Elderly nursing-home residents infected with COVID-19 (63–103 years old, male: 23.7%) | Single bolus | Intervention: single oral dose of 80,000 IU vitamin D3 during COVID-19 or in the preceding month (n = 57); Control: no vitamin D supplements (n = 9) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Cangiano et al. [30], 2021 | Prospective cohort, Italy | 157 residents of a nursing home after Sars-CoV-2 spread (80–100 years old, male: 28.5%) | 2 months | Intervention: vit D supplementation: 50,000 IU/month (n = 20); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 78) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Cereda et al. [15], 2020 | Retrospective cohort, Italy | COVID-19 outpatients (68.8± 10.6 years old, male: 48.4%) | 3 months | Intervention: supplemented (“mean intake of >1800 IU/day”) (n= 38); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 286) | 82.2 ± 37 | 28.2 ± 21.5 |

| Tertiary Prevention | ||||||

| Caballero-García et al. [26], 2021 | RCT, Spain | Patients in the recovery phase post hospitalization with COVID-19 infection (62.5 ± 1.5 years old, male: 100.0%) | 6 weeks | Intervention: vitamin D: , IU/day (n = 15); Control: placebo (n = 15) | 52.2 ± 4.5 | 53.0 ± 3.5 |

| Castillo et al. [3], 2020 | RCT, Spain | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (53.14 ± 1 0.77 years old, male: 59.0%) | 4 weeks | Intervention: 21,280 IU/day vitamin D on day 1, 3 and 7, and then weekly until discharge or ICU admission (n = 50); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 26) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Lakkireddy et al. [13], 2021 | RCT, India | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (20–83 years old, male: 75%) | 8–10 days | Intervention: 60,000 IU/day vitamin D (n = 44); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 43) | 40 ±15 | 42.5 ± 15 |

| Murai et al. [12], 2021 | RCT, Brazil | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (56.2 ± 14.4 years old, male: 46.1%) | 20 days | Intervention: single bolus of 200,000 IU vitamin D (n = 120); Control: placebo (n = 120) | 53 ± 25.2 | 51.5 ± 20.2 |

| Nogues et al. [25], 2021 | RCT, Spain | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (30–80 years old, male: 56.0%) | 30 days | Intervention: vitamin D: 21,620 IU on day 1, 10,810 IU on day 3, 7, 15, and 30) (n = 551); Control: placebo (n = 379) | 37.5 (22.5, 70) | 30 (8,47.5) |

| Sabico et al. [9], 2021 | RCT, Saudi Arabia | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (20–75 years, male: 47.8%) | 2 weeks | Intervention: vitamin D: 5000 IU/day (n = 36); Control: 1000 IU/day (n = 33) | 53.4 ± 2.9 | 63.5 ± 3.4 |

| Alcala-Diaz et al. [6], 2021 | Retrospective cohort, Spain | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (69 ± 15 years old, male: 59.0%) | 28 days | Intervention: vitamin D: 21,620 IU on day 1, 10,810 IU on day 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28) (n = 79); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 458) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Annweiler et al. [5], 2020 | Quasi-experimental with retrospective collection of data, France | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (78- 100 years old, male: 51.0%) | Not specified | Group 1: regularly supplemented with vitamin D (50,000 IU/month) (n = 29); Group 2: vitamin D supplementation initiated after COVID-19 diagnosis (80,000 IU bolus) (n = 16); Group 3: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 32) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Annweiler et al. [28], 2021 | Quasi-experimental with retrospective collection of data, France | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (78–100 years old, male: 51.0%) | Not specified | Intervention: regularly supplemented with vitamin D (50,000 IU/month or 800 IU/day) (n = 67); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 28) | 61.6 ± 35.4 | 73.9 ± 32.1 |

| Giannini et al. [35], 2021 | Retrospective cohort, Italy | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (74.0 ± 13.0 years old, male: 75%) | 2 days | Intervention: oral bolus of 200,000 IU vitamin D on the second and third day of hospital stay (n = 36); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 55) | 24 (12, 42) | 36 (19, 77) |

| Guven et al. [29], 2021 | Prospective cohort, Turkey | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (74 (61–82)) years old, male: 61.0%) | Single bolus | Intervention: single dose of 300,000 IU intramuscularly (n = 113); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 62) | 16.6 (12.6, 22.7) | 17.8 (14.2, 20.5) |

| Hernandez et al. [34], 2021 | Case–control, Spain | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (60.0 (59.0–75.0)) years old, male: 60.1%) | More than 3 months prior to hospital admission | Intervention: supplemented with vitamin D (“range from 10,000 IU/month, to 5600 IU/week or 25,000 IU/month”) (n = 19); Control: no vitamin D supplementation (n = 197) | 52.7 ± 14.7 | 34.5 ± 18 |

| Nogues et al. [33], 2021 | Prospective cohort, Spain | Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection (61.81 ± 15.5 years old, male: 59.0%) | 28 days | Intervention: vitamin D: 21,620 IU on day 1, 10,810 IU on day 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28) (n = 447); Control: no supplementation (n = 391) | 32.5 (20.0, 60.0) | 30 (20, 47.5) |

| Study | Selection Bias 1 | Selection Bias 2 | Performance Bias 3 | Attrition Bias 4 | Detection Bias 5 | Reporting Bias 6 | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prevention | |||||||

| Hosseini et al. [27] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Secondary prevention | |||||||

| Rastogi et al. [8] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Sanchez et al. [10] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Tertiary prevention | |||||||

| Castillo et al. [3] | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low |

| Caballero-Garcia et al. [26] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Lakkireddy et al. [13] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Murai et al. [12] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Nogues et al. [25] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Sabico et al. [9] | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Study | Q1 1 | Q2 2 | Q3 3 | Q4 4 | Q5 5 | Q6 6 | Q7 7 | Q8 8 | Q9 9 | Q10 10 | Overall Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary prevention | |||||||||||

| Abdulateef et al. [11] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Ma et al. [31] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Meltzer et al. [32] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Oristrell et al. [14] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Secondary prevention | |||||||||||

| Annweiler et al. [4] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Cangiano et al. [30] | Yes | No | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Cereda et al. [15] | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Tertiary prevention | |||||||||||

| Annweiler et al. [5] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Annweiler et al. [28] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Alcala-Diaz et al. [6] | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Giannini et al. [35] | Yes | No | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Guven et al. [29] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

| Nogues et al. [33] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

| Hernandez et al. [34] | Yes | No | No | No | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Some concerns |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hosseini, B.; El Abd, A.; Ducharme, F.M. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on COVID-19 Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102134

Hosseini B, El Abd A, Ducharme FM. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on COVID-19 Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(10):2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102134

Chicago/Turabian StyleHosseini, Banafsheh, Asmae El Abd, and Francine M. Ducharme. 2022. "Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on COVID-19 Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 14, no. 10: 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102134

APA StyleHosseini, B., El Abd, A., & Ducharme, F. M. (2022). Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on COVID-19 Related Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 14(10), 2134. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102134