Feasibility of a Home-Delivery Produce Prescription Program to Address Food Insecurity and Diet Quality in Adults and Children

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Intervention Design

2.2. Overview of Study Design

2.3. Measures of Feasibility (Enrollment, Survey Response, Satisfaction, Participation, and Retention)

2.4. Baseline and Post-Intervention Questionnaire

2.4.1. Demographics and Anthropometrics

2.4.2. Food Insecurity (FI) Variables

2.4.3. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption

2.4.4. Modified Family and Nutrition and Physical Activity (FNPA)

2.4.5. Modified Perceived Health Competence Scale (PHCS)

2.4.6. Modified Food Resource Management (FRM)

2.5. Qualitative Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Program Delivery

3.2. Feasibility

3.2.1. Rate of Enrollment

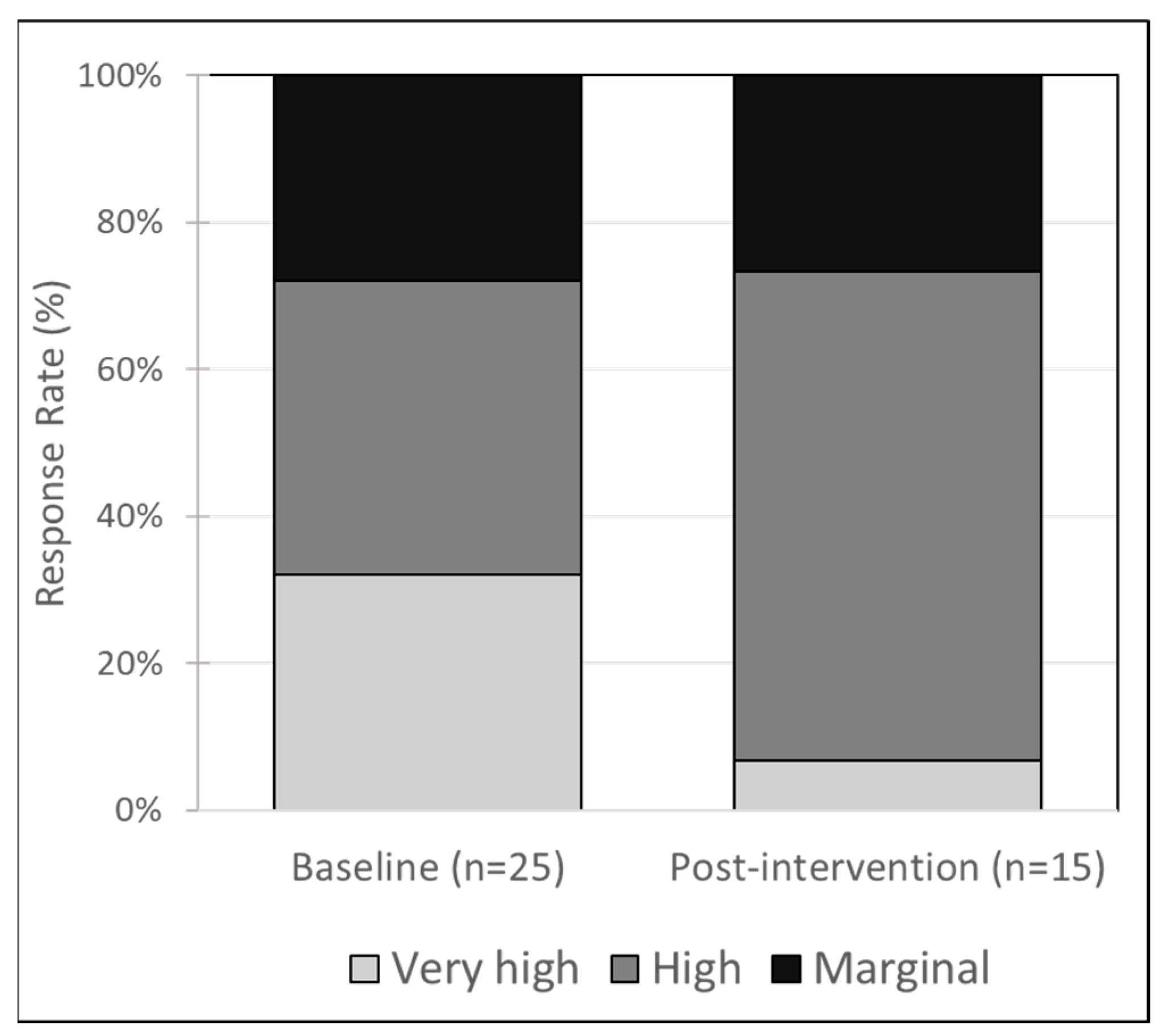

3.2.2. Survey Response

3.2.3. Satisfaction

3.2.4. Participation

3.2.5. Retention

3.3. Baseline Demographics and Anthropometrics

3.4. Food Insecurity (FI)

3.5. Food Frequency and Feeding Habits

3.5.1. Child under Age 1 Year Old

3.5.2. Over Age 1 Year Old, (or Age < 1 Who Were Fed Solid Food)

3.5.3. Adults

3.6. Exploring the Relationship between FI and Fruit and Vegetable Intake

3.7. Home Environment, Self-Efficacy, and Food Resource Management

3.8. Comparing Finishers and Non-Finishers

3.9. Qualitative Interviews

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Major Findings

4.2. Fruit and Vegetable Intake Improved in a Subgroup of Participants in a Similar Magnitude to Other Produce Prescription Studies but Consumption Was Still Below Recommended Levels

4.3. FI Scores Were Unchanged but Perceived FI Severity May Be an Important Outcome to Explore as Well as the Relationship between FI and Fruit and Vegetable Intake

4.4. Program Improvements, Scalability, and Sustainability

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2020; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Volume ERR-298.

- Leung, C.W.; Epel, E.S.; Ritchie, L.D.; Crawford, P.B.; Laraia, B.A. Food insecurity is inversely associated with diet quality of lower-income adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1943–1953.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Food Insecurity and Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muennig, P.; Fiscella, K.; Tancredi, D.; Franks, P. The relative health burden of selected social and behavioral risk factors in the United States: Implications for policy. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1758–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, T.E.; Scherer, E.A.; Fleegler, E.W.; Hassan, A. Food Insecurity and the Burden of Health-Related Social Problems in an Urban Youth Population. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 57, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drennen, C.R.; Coleman, S.M.; Ettinger de Cuba, S.; Frank, D.A.; Chilton, M.; Cook, J.T.; Cutts, D.B.; Heeren, T.; Casey, P.H.; Black, M.M. Food Insecurity, Health, and Development in Children Under Age Four Years. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20190824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dush, J.L. Adolescent food insecurity: A review of contextual and behavioral factors. Public Health Nurs. 2020, 37, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, R.; Hammarlund, R.; Bouquet, M.; Ojewole, T.; Kirby, D.; Grizzaffi, J.; McMahon, P. Parent and Child Reports of Food Insecurity and Mental Health: Divergent Perspectives. Ochsner. J. 2018, 18, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arenas, D.J.; Thomas, A.; Wang, J.; DeLisser, H.M. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Depression, Anxiety, and Sleep Disorders in US Adults with Food Insecurity. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 2874–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, T.W. FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Commit to End Hunger and Malnutrition and Build Sustainable Resilient Food Systems. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/09/23/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-commit-to-end-hunger-and-malnutrition-and-build-sustainable-resilient-food-systems/ (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Boeing, H.; Bechthold, A.; Bub, A.; Ellinger, S.; Haller, D.; Kroke, A.; Leschik-Bonnet, E.; Müller, M.J.; Oberritter, H.; Schulze, M.; et al. Critical review: Vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Hu, F.B. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014, 349, g4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharifi, Y.; Payab, M.; Mohammadi-Vajari, E.; Aghili, S.M.M.; Sharifi, F.; Mehrdad, N.; Kashani, E.; Shadman, Z.; Larijani, B.; Ebrahimpur, M. Association between cardiometabolic risk factors and COVID-19 susceptibility, severity and mortality: A review. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2021, 20, 1743–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025, 9th ed.; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Lee, S.H.; Moore, L.V.; Park, S.; Harris, D.M.; Blanck, H.M. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.A.; Moore, L.V.; Galuska, D.; Wright, A.P.; Harris, D.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Merlo, C.L.; Nihiser, A.J.; Rhodes, D.G. Vital signs: Fruit and vegetable intake among children—United States, 2003–2010. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2014, 63, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Kubik, M.Y.; Fulkerson, J.A. Diet Quality and Fruit, Vegetable, and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption by Household Food Insecurity among 8- to 12-Year-Old Children during Summer Months. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1695–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mofleh, D.; Ranjit, N.; Chuang, R.-J.; Cox, J.N.; Anthony, C.; Sharma, S.V. Association Between Food Insecurity and Diet Quality Among Early Care and Education Providers in the Pennsylvania Head Start Program. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, 200602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, N.N. Adolescent-Reported Food Insecurity: Correlates of Dietary Intake and School Lunch Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noia, J.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C. Determinants of fruit and vegetable intake in low-income children and adolescents. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertmann, F.; Rogomentich, K.; Belarmino, E.H.; Niles, M.T. The Food Bank and Food Pantries Help Food Insecure Participants Maintain Fruit and Vegetable Intake During COVID-19. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 673158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewit, E.L.; Meissen-Sebelius, E.M.; Shook, R.P.; Pina, K.A.; De Miranda, E.D.; Summar, M.J.; Hurley, E.A. Beyond clinical food prescriptions and mobile markets: Parent views on the role of a healthcare institution in increasing healthy eating in food insecure families. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; Alexander, T.; Slaughter-Acey, J.C.; Berge, J.; Widome, R.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Barriers to Accessing Healthy Food and Food Assistance During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Racial Justice Uprisings: A Mixed-Methods Investigation of Emerging Adults’ Experiences. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 1679–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litton, M.M.; Beavers, A.W. The Relationship between Food Security Status and Fruit and Vegetable Intake during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2021, 13, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, M.; Rosa, E.; Heasley, C.; Asif, A.; Dodd, W.; Richter, A. Promoting Healthy Food Access and Nutrition in Primary Care: A Systematic Scoping Review of Food Prescription Programs. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldheer, S.; Scartozzi, C.; Knehans, A.; Oser, T.; Sood, N.; George, D.R.; Smith, A.; Cohen, A.; Winkels, R.M. A Systematic Scoping Review of How Healthcare Organizations Are Facilitating Access to Fruits and Vegetables in Their Patient Populations. J. Nutr. 2020, 150, 2859–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrington, C.M.; Hohensee, T.E.; Tallman, N.; Gadomski, A.M. A pilot study of an online produce market combined with a fruit and vegetable prescription program for rural families. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 17, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxe-Custack, A.; Lachance, J.; Jess, J.; Hanna-Attisha, M. Influence of a Pediatric Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program on Child Dietary Patterns and Food Security. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxe-Custack, A.; LaChance, J.; Hanna-Attisha, M. Child Consumption of Whole Fruit and Fruit Juice Following Six Months of Exposure to a Pediatric Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program. Nutrients 2019, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esquivel, M.K.; Higa, A.; Hitchens, M.; Shelton, C.; Okihiro, M. Keiki Produce Prescription (KPRx) Program Feasibility Study to Reduce Food Insecurity and Obesity Risk. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2020, 79, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Aiyer, J.N.; Raber, M.; Bello, R.S.; Brewster, A.; Caballero, E.; Chennisi, C.; Durand, C.; Galindez, M.; Oestman, K.; Saifuddin, M.; et al. A pilot food prescription program promotes produce intake and decreases food insecurity. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 922–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridberg, R.A.; Bell, J.F.; Merritt, K.E.; Harris, D.M.; Young, H.M.; Tancredi, D.J. Effect of a Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program on Children’s Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2019, 16, E73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, L.J.; VanWassenhove-Paetzold, J.; Thomas, K.; Bancroft, C.; Ziatyk, E.Q.; Kim, L.S.; Shirley, A.; Warren, A.C.; Hamilton, L.; George, C.V.; et al. Impact of a Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program on Health Outcomes and Behaviors in Young Navajo Children. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabili, C.; Briefel, R.; Forrestal, S.; Gabor, V.; Chojnacki, G. A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of a Home-Delivered Food Box on Children’s Diet Quality in the Chickasaw Nation Packed Promise Project. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, S59–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atanasova, P.; Kusuma, D.; Pineda, E.; Frost, G.; Sassi, F.; Miraldo, M. The impact of the consumer and neighbourhood food environment on dietary intake and obesity-related outcomes: A systematic review of causal impact studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 299, 114879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlosser, A.V.; Joshi, K.; Smith, S.; Thornton, A.; Bolen, S.D.; Trapl, E.S. The coupons and stuff just made it possible: Economic constraints and patient experiences of a produce prescription program. Transl. Behav. Med. 2019, 9, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gearing, M.; Lewis, M.; Wilson, C.; Bozzolo, C.; Hansen, D. Barriers That Constrain the Adequacy of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Allotments: In-depth Interview Findings; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Jensen, M.; Pokorney, P.; Ehrbeck-Malhotra, R.; Kelley, B. Still Minding the Grocery Gap; D.C. Hunger Solutions: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hager, E.R.; Quigg, A.M.; Black, M.M.; Coleman, S.M.; Heeren, T.; Rose-Jacobs, R.; Cook, J.T.; Ettinger de Cuba, S.A.; Casey, P.H.; Chilton, M.; et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e26–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooper, L.A.; Roter, D.L.; Johnson, R.L.; Ford, D.E.; Steinwachs, D.M.; Powe, N.R. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003, 139, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2000.

- Subar, A.F.; Thompson, F.E.; Kipnis, V.; Midthune, D.; Hurwitz, P.; Mcnutt, S.; Mcintosh, A.; Rosenfeld, S. Comparative Validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute Food Frequency Questionnaires. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 154, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Scoring the All-Day Screener. 2021. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/diet/screeners/fruitveg/scoring/allday.html#how (accessed on 1 May 2022).

- Ihmels, M.A.; Welk, G.J.; Eisenmann, J.C.; Nusser, S.M. Development and preliminary validation of a Family Nutrition and Physical Activity (FNPA) screening tool. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, M.S.; Wallston, K.A.; Smith, C.A. The development and validation of the Perceived Health Competence Scale. Health Educ. Res. 1995, 10, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinard, C.A.; Uvena, L.M.; Quam, J.B.; Smith, T.M.; Yaroch, A.L. Development and Testing of a Revised Cooking Matters for Adults Survey. Am. J. Health Behav. 2015, 39, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. Usual Dietary Intakes: Food Intakes, U.S. Population, 2007–2010; Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, A.K.; Mennella, J.A. Innate and learned preferences for sweet taste during childhood. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Spill, M.K.; Johns, K.; Callahan, E.H.; Shapiro, M.J.; Wong, Y.P.; Benjamin-Neelon, S.E.; Birch, L.; Black, M.M.; Cook, J.T.; Faith, M.S.; et al. Repeated exposure to food and food acceptability in infants and toddlers: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 978S–989S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, J.J.; Fiese, B.H.; Team, S.K.R. Family food involvement is related to healthier dietary intake in preschool-aged children. Appetite 2018, 126, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshfegh, A.J.; Rhodes, D.G.; Baer, D.J.; Murayi, T.; Clemens, J.C.; Rumpler, W.V.; Paul, D.R.; Sebastian, R.S.; Kuczynski, K.J.; Ingwersen, L.A.; et al. The US Department of Agriculture Automated Multiple-Pass Method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lenthe, F.J.; Jansen, T.; Kamphuis, C.B.M. Understanding socio-economic inequalities in food choice behaviour: Can Maslow′s pyramid help? Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puddephatt, J.-A.; Keenan, G.S.; Fielden, A.; Reaves, D.L.; Halford, J.C.G.; Hardman, C.A. ‘Eating to survive’: A qualitative analysis of factors influencing food choice and eating behaviour in a food-insecure population. Appetite 2020, 147, 104547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Castner, L.; Wakar, B.; Wroblewska, K.; Trippe, C.; Cole, N. Benefit Redemption Patterns in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in Fiscal Year 2017; USDA, Food and Nutrition Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Tseng, M.; Mastrantonio, C.; Glanz, H.; Volpe, R.J.; Neill, D.B.; Nazmi, A. Fruit and Vegetable Purchasing Patterns and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation: Findings From a Nationally Representative Survey. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1633–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamelin, A.-M.; Habicht, J.-P.; Beaudry, M. Food Insecurity: Consequences for the Household and Broader Social Implications. J. Nutr. 1999, 129, 525S–528S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saxe-Custack, A.; Lachance, J.; Hanna-Attisha, M.; Ceja, T. Fruit and Vegetable Prescriptions for Pediatric Patients Living in Flint, Michigan: A Cross-Sectional Study of Food Security and Dietary Patterns at Baseline. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Variable | Description | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) | Female | 25 (100%) |

| Age (mean, standard deviation, sd) | Age in years | 29.9 (5.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2) and BMI category distribution (n, %) | BMI (mean, sd) | 33.7 (9.4) |

| <25 | 5 (20%) | |

| 25–30 | 6 (24%) | |

| 30–35 | 3 (12%) | |

| >35 | 11 (44%) | |

| Diagnosis of high BP or DM (n, % yes) | High BP | 10 (40%) |

| DM | 2 (8%) | |

| Reference child age group (n, %) | 0–1 years | 11 (44%) |

| >1–5 years | 14 (56%) | |

| Race (n, %) | African-American | 25 (100%) |

| Employment status (n, %) | Working full-time | 4 (16%) |

| Working part-time | 6 (24%) | |

| Going to school or apprenticeship | 2 (8%) | |

| Unemployed | 10 (40%) | |

| Self-employed | 1 (4%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (8%) | |

| Level of education (n, %) | Less than high school | 3 (12%) |

| High school diploma or GED | 12 (48%) | |

| Some college | 7 (28%) | |

| College graduate | 1 (4%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (8%) | |

| Level of income (n, %) | Less than USD 10,000 a year | 10 (40%) |

| USD 10,001–USD 25,000 a year | 3 (12%) | |

| USD 25,001–USD 50,000 a year | 4 (16%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 8 (32%) | |

| Marital status (n, %) | Never married/single | 18(72%) |

| Married or unmarried couple | 3 (12%) | |

| Divorced | 2 (8%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (8%) | |

| Household occupants (median) | number of adults | 1 |

| number of children (age 0–17) | 3 | |

| Governmental support program participation (n, %) | FRPS * | 8 (32%) |

| SNAP | 16 (64%) | |

| SSI * | 7 (28%) | |

| TANF * | 14 (56%) | |

| WIC | 14 (56%) | |

| None | 2 (8%) |

| Theme Name | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| Theme 1. Reduced Food Hardship Subtheme:

| “They deliver [the FLiPRx produce boxes] so I don’t have to go stand in line, I don’t have to deal with the crowd. It’s just delivery at the front door without me having to order, so that just saves a little time and me trying to get food or going to the grocery store, especially if I’m at work or with the children and don’t have time to take them [or] car’s gone out (Participant #3)” “We love string beans. I was always into my veggies, but I couldn’t afford as much as I get from you all; I couldn’t afford the different varieties” (Participant #17). “[The produce] helps a lot, far as the nutrition, the vegetables and the fruit—I mean different kinds of veggies—for me and my daughter and it just helps us and it saves me money because sometimes I can’t get the veggies and stuff like that that I need because of my finances. Because of the pandemic I lost my job so it helps a lot” (Participant #17). “What if something happens with my SNAP? I can’t just fully depend on that. And now I know that I still have my produce coming from y’all. … It hasn’t been the case yet, but you don’t know what’s gonna happen in the future, so I don’t wanna end the [FLiPRx] program and, you know, something happens with the SNAP, now it’s gotta come out of my pocket. I know I still have the bag coming” (Participant #13). |

| Theme 2. Family-driven Behavior Change Subtheme:

| ‘[I tried] beets. I’ve always thought beets were super disgusting. My mom loves them but we watched one of the [recipe] videos where she was making roasted beets and I was like, ‘oh, okay, I’m gonna try that’ and I did and it was actually really good, so I was like, ‘oh cool!’” (Participant #8) “[The program] has been great not just for the kids. Like for me, I’m consuming more of the fresh produce. It’s done a lot for me and my health. I have been able to stop taking my blood pressure medication so that is a plus. I learned how to give myself the right foods in the right order, to make sure I’m getting enough of the right stuff, and that’s been a big positive” (Participant #19). “[The recipe videos] are pretty cool, it was just like that they’ve really taken the time out and really teaching step by step, you know, especially for those who may not know how to cook or know what to do and I found that pretty cool. […] It’s like they’re getting the hands-on training but it’s virtual and I find that pretty awesome” (Participant #3). |

| Theme 3. Economic Flexibility Subtheme:

| “[The program] made it so that I was more conscious about what I was purchasing. […] It made me think about meal planning more as opposed to, ‘okay I’m just gonna go and get what I normally get and get out.’ […] If I have a little bit of [FLiP produce], then I can put money that was allotted for [that produce] over to maybe a non-SNAP item or maybe I can get more fruits, more noodles (since that’s what [my son] likes), more meats to go with it to kinda stretch the money a little longer. So it’s actually helped my budget as far as I can now move—my grandmother calls it ‘moving her blocks around’” (Participant #8). “Being the mom in a house with six kids, three adults, you know, sometimes things come up short with my SNAP benefits. I don’t have all the people in my home on my SNAP benefits […] so sometimes we come up short and I have to make those vegetable dishes […] because that’s what we have for us to eat” (Participant #2). |

| Theme 4. Enhanced family bonding Subtheme:

| “My two girls love it, especially like cooking, making the little recipes that you guys send in the bag, my children love it. […] They get to prep the food, they get to like, you know, stir the food, make the food, […] they stir the food, sometimes I would show them how to, like, chop the food, like I would guide them with the utensil, things like that” (Participant #4) “That [corn salsa recipe] was pretty good. My sister actually watched the video with me and [we] tried it and it turned out pretty good, it was a little spicy, but it was good” (Participant #10) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fischer, L.; Bodrick, N.; Mackey, E.R.; McClenny, A.; Dazelle, W.; McCarron, K.; Mork, T.; Farmer, N.; Haemer, M.; Essel, K. Feasibility of a Home-Delivery Produce Prescription Program to Address Food Insecurity and Diet Quality in Adults and Children. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102006

Fischer L, Bodrick N, Mackey ER, McClenny A, Dazelle W, McCarron K, Mork T, Farmer N, Haemer M, Essel K. Feasibility of a Home-Delivery Produce Prescription Program to Address Food Insecurity and Diet Quality in Adults and Children. Nutrients. 2022; 14(10):2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102006

Chicago/Turabian StyleFischer, Laura, Nia Bodrick, Eleanor R. Mackey, Anthony McClenny, Wayde Dazelle, Kristy McCarron, Tessa Mork, Nicole Farmer, Matthew Haemer, and Kofi Essel. 2022. "Feasibility of a Home-Delivery Produce Prescription Program to Address Food Insecurity and Diet Quality in Adults and Children" Nutrients 14, no. 10: 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102006

APA StyleFischer, L., Bodrick, N., Mackey, E. R., McClenny, A., Dazelle, W., McCarron, K., Mork, T., Farmer, N., Haemer, M., & Essel, K. (2022). Feasibility of a Home-Delivery Produce Prescription Program to Address Food Insecurity and Diet Quality in Adults and Children. Nutrients, 14(10), 2006. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14102006