Effect of Intake of Food Hydrocolloids of Bacterial Origin on the Glycemic Response in Humans: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis

Abstract

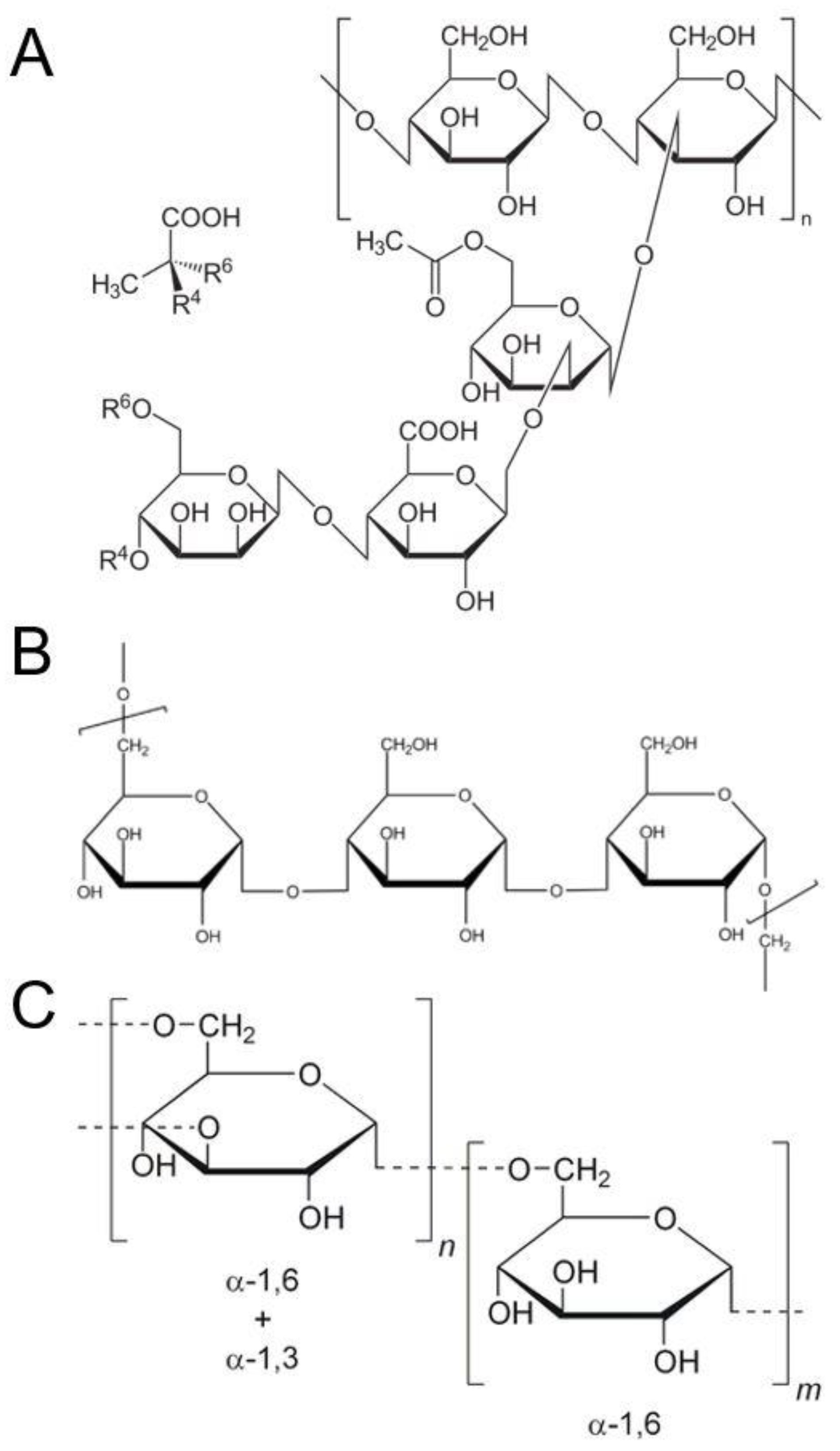

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion

2.2. Search Strategy

- (hydrocolloid* or polysaccharid*).ti,ab.

- (xanthan or xylinan or acetan or “hyaluronic acid” or gellan or curdlan or pullulan or dextran or scleroglucan or schizophyllan or cyanobacterial).ti,ab exp hydrocolloid/

- 1 or 2

- (“glyc?emic index*” or “glyc?emic response*” or “glyc?emic load*”).ti,ab.

- glycemic index/

- glycemic load/

- 4 or 5 or 6

- ((glucose or sugar) adj2 blood).ti,ab.

- ((glucose or sugar) adj2 plasma).ti,ab.

- Blood Glucose/

- 8 or 9 or 10

- 7 or 11

- 3 and 12

- limit 13 to human

2.3. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Synthesis

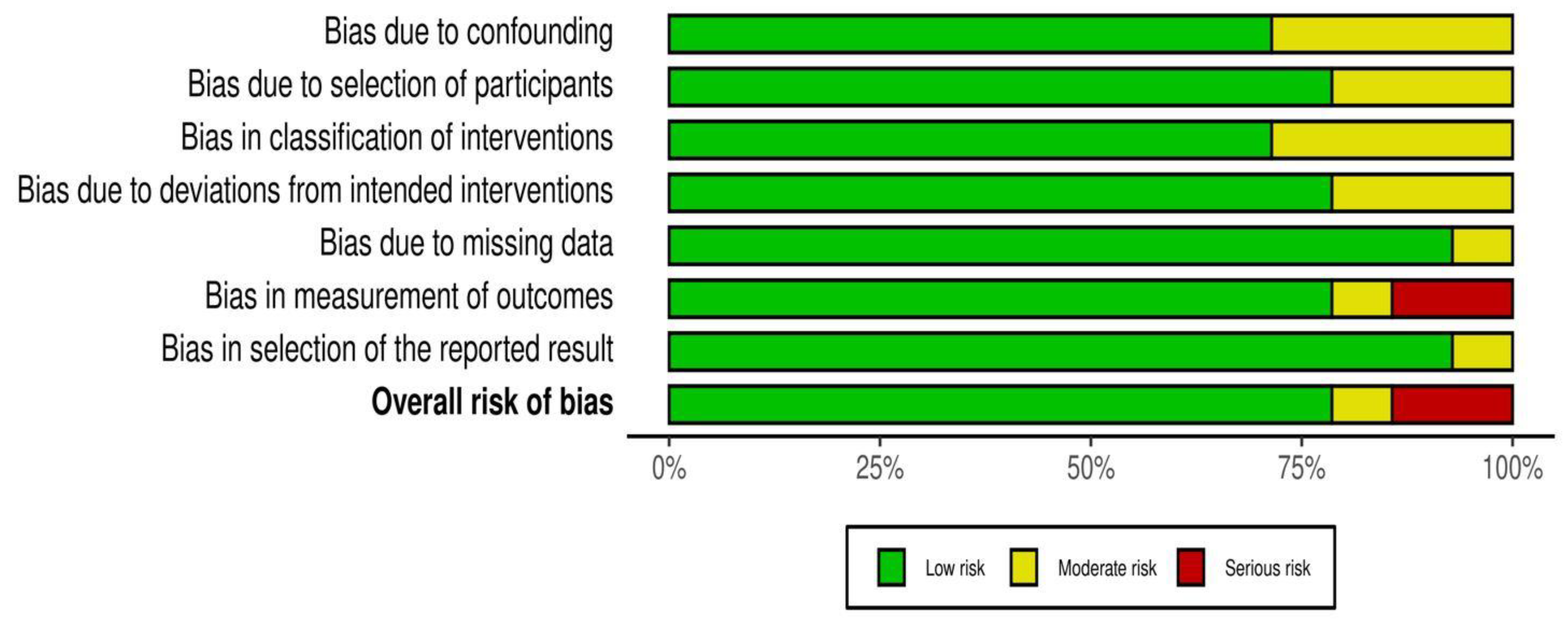

2.4. Risk of Bias across Studies

3. Results

3.1. Pullulan and Glycemic Response

3.2. Xanthan and Glycemic Response

3.3. Dextran and Glycemic Response

3.4. Appetite

3.5. Tolerance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeFronzo, R.A.; Ferrannini, E.; Groop, L.; Henry, R.R.; Herman, W.H.; Holst, J.J.; Hu, F.B.; Kahn, C.R.; Raz, I.; Shulman, G.I.; et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SACN. Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition: Carbohydrates and Health Report; Public Health England: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nalysnyk, L.; Hernandez-Medina, M.; Krishnarajah, G. Glycaemic variability and complications in patients with diabetes mellitus: Evidence from a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2010, 12, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, N.A.; Holgate, A.M.; Read, N.W. Does guar gum improve post-prandial hyperglycemia in humans by reducing small intestinal contact area. Br. J. Nutr. 1984, 52, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackburn, N.A.; Redfern, J.S.; Jarjis, H.; Holgate, A.M.; Hanning, I.; Scarpello, J.H.B.; Johnson, I.T.; Read, N.W. The mechanism of action of guar gum in improving glucose tolerance in man. Clin. Sci. 1984, 66, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarjis, H.A.; Blackburn, N.A.; Redfern, J.S.; Read, N.W. The effect of ispaghula (Fybogel and Metamucil) and guar gum on glucose tolerance in man. Br. J. Nutr. 1984, 51, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, D.J.A.; Thorne, M.J.; Wolever, T.M.S.; Jenkins, A.L.; Rao, A.V.; Thompson, L.U. The effect of starch-protein interaction in wheat on the glycemic response and rate of in vitro digestion. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1987, 45, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.J.; Liu, Q.; Lim, S.T. Texture and in vitro digestibility of white rice cooked with hydrocolloids. Cereal Chem. 2007, 84, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartois, A.; Singh, J.; Kaur, L.; Singh, H. Influence of guar gum on the in vitro starch digestibility-rheological and microstructural characteristics. Food Biophys. 2010, 5, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneeman, B.O.; Gallaher, D. Effects of dietary fiber on digestive enzyme activity and bile acids in the small intestine. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1985, 180, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrig, K.L. The physiological effects of dietary fiber-a review. Food Hydrocoll. 1988, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Jeon, H.-J.; Yoon, S.; Lee, S.-M. Hydrocolloids decrease the digestibility of corn starch, soy protein, and skim milk and the antioxidant capacity of grape juice. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 20, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boers, H.M.; Seijen-ten Hoorn, J.; Mela, D.J. Effect of Hydrocolloids on Lowerign Blood Glucose; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2016; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gidley, M.J. Hydrocolloids in the digestive tract and related health implications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 18, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouseti, O.; Jaime-Fonseca, M.R.; Fryer, P.J.; Mills, C.; Wickham, M.S.J.; Bakalis, S. Hydrocolloids in human digestion: Dynamic in-vitro assessment of the effect of food formulation on mass transfer. Food Hydrocoll. 2014, 42, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phillips, G.O.; Williams, P.A. Handbook of Hydrocolloids; Phillips, G.O., Williams, P.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oguzhan, P.; Yangilar, F. Pullulan: Production and usage in food ındustry. Afr. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 4, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Grp, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Br. Med. J. 2009, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernan, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savovic, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br. Med. J. 2016, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Br. Med. J. 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wolf, B.W.; Garleb, K.A.; Choe, Y.S.; Humphrey, P.M.; Maki, K.C. Pullulan is a slowly digested carbohydrate in humans. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spears, J.K.; Karr-Lilienthal, L.K.; Grieshop, C.M.; Flickinger, E.A.; Wolf, B.W.; Fahey, G.C. Glycemic, insulinemic, and breath hydrogen responses to pullulan in healthy humans. Nutr. Res. 2005, 25, 1029–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.L.; Nikhanj, S.D.; Timm, D.A.; Thomas, W.; Slavin, J.L. Evaluation of the effect of four fibers on laxation, gastrointestinal tolerance and serum markers in healthy humans. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2010, 56, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peters, H.P.F.; Ravestein, P.; van der Hijden, H.; Boers, H.M.; Mela, D.J. Effect of carbohydrate digestibility on appetite and its relationship to postprandial blood glucose and insulin levels. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Osilesi, O.; Trout, D.L.; Glover, E.E.; Harper, S.M.; Koh, E.T.; Behall, K.M.; Odorisio, T.M.; Tartt, J. Use of xanthan gum in dietary management of diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 42, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eastwood, M.A.; Brydon, W.G.; Anderson, D.M.W. The dietary effects of xanthan gum in man. Food Addit. Contam. 1987, 4, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.A.; Blackburn, N.A.; Craigen, L.; Davison, P.; Tomlin, J.; Sugden, K.; Johnson, I.T.; Read, N.W. Viscosity of food gums determined in vitro related to their hypoglycemic actions. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1987, 46, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquin, J.; Bedard, A.; Lemieux, S.; Tajchakavit, S.; Turgeon, S.L. Effects of juices enriched with xanthan and beta-glucan on the glycemic response and satiety of healthy men. App. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 38, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuwa, M.; Nakanishi, Y.; Moritaka, H. Effect of xanthan gum on blood sugar level after cooked rice consumption. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2016, 22, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, H.; Nishikawa, Y.; Kure, K.; Tsuda, K.; Hosokawa, M. The addition of xanthan gum to enteral nutrition suppresses postprandial glycemia in humans. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 2018, 64, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naharudin, M.N.; Adams, J.; Richardson, H.; Thomson, T.; Oxinou, C.; Marshall, C.; Clayton, D.J.; Mears, S.A.; Yusof, A.; Hulston, C.J.; et al. Viscous placebo and carbohydrate breakfasts similarly decrease appetite and increase resistance exercise performance compared with a control breakfast in trained males. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 124, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bloom, W.L.; Wilhelmi, A.E. Dextran as a source of liver glycogen and blood reducing substance. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1952, 81, 501–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joelson, R.H. The effect of oral dextran on blood glucose. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1956, 4, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhan, F.B.; Hashemi, Z.; Herrera, M.C.A.; Turner, K.; Windeler, S.; Ganzle, M.G.; Chan, C.B. Ingestion of isomalto-oligosaccharides stimulates insulin and incretin hormone secretion in healthy adults. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klosterbuer, A.S.; Thomas, W.; Slavin, J.L. Resistant starch and pullulan reduce postprandial glucose, insulin, and GLP-1, but have no effect on satiety in healthy humans. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11928–11934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paquet, E.; Bedard, A.; Lemieux, S.; Turgeon, S.L. Effects of apple juice-based beverages enriched with dietary fibres and xanthan gum on the glycemic response and appetite sensations in healthy men. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2014, 4, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, M.S.M.; Henry, C.J. Reducing the glycemic impact of carbohydrates on foods and meals: Strategies for the food industry and consumers with special focus on Asia. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 670–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ojo, O.; Feng, Q.Q.; Ojo, O.O.; Wang, X.H. The role of dietary fibre in modulating gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortesen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; DiDomenico, A.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Lambre, C.; Leblanc, J.C. Re-evaluation of xanthan gum (E 415) as a food additive. EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS). EFSA J. 2017, e04909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halford, J.C.G.; Masic, U.; Marsaux, C.F.M.; Jones, A.J.; Lluch, A.; Marciani, L.; Mars, M.; Vinoy, S.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.; Mela, D.J. Systematic review of the evidence for sustained efficacy of dietary interventions for reducing appetite or energy intake. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1329–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author Year Country | Study Design | Intervention Acute/Long-Term and Details | Comparator | Duration of Glucose Assessment | Washout | n | Gender | Age | Glucose Results | Appetite Results | Other Outcomes Reported |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bloom 1952 USA | One-way | Acute intervention 100 mL of 20% dextran (n = 2); 200 mL of 20% dextran (n = 2) | N/A | 2 h | N/A | 4 | N/K | N/K | Low rise in blood sugar over 2 h | N/A | N/A |

| Joelson 1956 USA | One-way | Acute intervention 400 mL of 5% dextran | N/A | 3 h | N/A | 5 | N/K | N/K | No increase in postprandial blood sugar | N/A | N/A |

| Osilesi 1985 USA | Crossover | Long-term intervention Xanthan containing muffins 12 g/day for 6 weeks | xanthan-free muffins for 6 weeks | 2 h | no wash out | 9 DP, 4 HV | M = 2,F = 7 M = 1,F = 3 | 53 ± 4 37 ± 5 | Prior feeding of xanthan induced reduction in post-load glucose by 31% in patients and 25% in HV | Episodic increased fullness no gut symptoms | Reduction in fasting glucose and total cholesterol in both groups. No significant change in insulin, gastrin, and GIP, and triglycerides in patients |

| Eastwood 1987 UK | Before-after | Long-term intervention Xanthan as fluid gel three times daily for 23 days, total between 10.4 and 12.9 g/day | N/A | 4 h | N/A | 5 HV | M = 5 | 26–50 | No significant effect on plasma glucose | N/A | Increased fecal weight and intestinal transit. No effect on plasma biochemistry, hematological indices, urinalysis, insulin, serum immunoglobulins, triglycerides, phospholipids and cholesterol |

| Edwards 1987 UK | Randomized crossover | Acute intervention 50 g glucose drink and (1) 2.5 g xanthan; (2) xanthan and locust bean gum; (3) xanthan/Mey; (4) locust bean gum or guar | 50 g glucose control drink | 2 h | N/K | 16 HV | M = 12 F = 4 | 18–25 | Significant reduction in glucose AUC | N/A | Reduction in insulin AUC. No change in gastric emptying |

| Wolf 2003 USA | Randomized crossover | Acute intervention 474 mL beverage with pullulan 0.1 g/1 mL = 47 g | Maltodextrin beverage | 3 h | 5–13 days | 28 out of 36 HV | M = 22 F = 14 | 18–75 | Positive incremental AUC reduced by 50% | N/A | Increased breath hydrogen concentration |

| Spears 2005 USA | Randomized crossover | Acute intervention beverage with low molecular weight pullulan 50 g | Maltodextrin beverage | 3 h | 4–14 days | 34 HV | M = 19 F = 15 | 20–39 | No effect on incremental plasma glucose response | N/A | Higher breath hydrogen at later time points. Serum insulin lower during the first 90 min postprandially, higher at 3 h. No effect on symptoms |

| Stewart 2010 USA | Single-blind randomized crossover | Long-term intervention Sauce mixed with 12 g/day of (1) pullulan; (2) resistant starch; (3) soluble fiber; (4) soluble corn fiber give for 14 days | Maltodextrin | Only fasting time point | 21 days | 20 HV | M = 10 F = 10 | 32 ± 5 38 ± 4 | No significant change in fasting glucose | No change in hunger | Increase in gastrointestinal symptoms. No change in ad libitum diet, stool parameters, trigycerides, cholesterol, insulin, C-reactive protein, ghrelin, blood pressure and body weight |

| Peters 2011 Netherland | Randomized crossover | Acute intervention Drink containing 15 g pullulan as (1) long-chain; (2) medium-chain | Maltodextrin drink | 5 h | week | 35 HV | F = 27 M = 8 | 20–59 | Subset of n = 12 tested for glucose. Significant increase of AUC 0–150 min in medium-chain and long-chain | Significant reduction in long-chain group 0–150 min | Breath hydrogen was significantly higher for both chain lengths. Ony occasional complaints of symptoms. Insulin was lower for long-chain pullulan |

| Paquin 2013 Canada | Randomized crossover | Acute intervention 4 juices 300 mL: (1) xanthan 0.18 g/100 mL; (2) B-glucan; (3) xanthan + B-glucan 0.09 g/100 mL; (4) control | Control juice | 2 h | 1 week | 14 HV | M | 20–50 | No difference in AUC compared to control group | No change | No significant change in insulin |

| Fuwa 2016 Japan | Crossover | Acute intervention 250 g Rice with: (1) xanthan added during rice cooking 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5%; (2) xanthan mixed with cooked rice at 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5% | 250 g cooked rice | 2 h | >3 days | 11 HV | F | 19–39 | Significant decrease in postprandial glucose at 15, 30 and 45 min in >1, 1.5% added during rice cooking group and in xanthan sol group at 15–60 min | N/A | N/A |

| Tanaka 2018 Japan | Ordered intervention | Acute intervention 150 mL enteral formula + 1.0% xanthan | 150 mL enteral formula | 2 h | 7 days | 5 HV | M = 2 F = 3 | 21–22 | AUC glucose 48% smaller than control | N/A | N/A |

| Naharudin 2020 UK | Randomized double blind | Acute intervention Semi-solid fasts containing xanthan 0.1 g/kg of body weight. One with and one without added carbohydrate | Water as control | 105 min | >4 days | 22 | M = 22 | 23 ± 3 | No significant change in plasma glucose | Significant reduction in hunger, increase in fullness compared to control | Significant differences in insulin and ghrelin in the added carbohydrate group |

| Subhan 2020 Canada | Trial 1. Single-blind randomized crossover | Acute intervention 20 g of: (1) isomalto-oligosaccharides; (2) dextran; (3) maltodextrin; (4) dextrose reference | Water as control | 2 h | 1 week | 12 HV | N/K | 18–75 | Dextran did not increase plasma glucose compared with water | N/A | N/A |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshammari, N.A.; Taylor, M.A.; Stevenson, R.; Gouseti, O.; Alyami, J.; Muttakin, S.; Bakalis, S.; Lovegrove, A.; Aithal, G.P.; Marciani, L. Effect of Intake of Food Hydrocolloids of Bacterial Origin on the Glycemic Response in Humans: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2407. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072407

Alshammari NA, Taylor MA, Stevenson R, Gouseti O, Alyami J, Muttakin S, Bakalis S, Lovegrove A, Aithal GP, Marciani L. Effect of Intake of Food Hydrocolloids of Bacterial Origin on the Glycemic Response in Humans: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Nutrients. 2021; 13(7):2407. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072407

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshammari, Norah A., Moira A. Taylor, Rebecca Stevenson, Ourania Gouseti, Jaber Alyami, Syahrizal Muttakin, Serafim Bakalis, Alison Lovegrove, Guruprasad P. Aithal, and Luca Marciani. 2021. "Effect of Intake of Food Hydrocolloids of Bacterial Origin on the Glycemic Response in Humans: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis" Nutrients 13, no. 7: 2407. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072407

APA StyleAlshammari, N. A., Taylor, M. A., Stevenson, R., Gouseti, O., Alyami, J., Muttakin, S., Bakalis, S., Lovegrove, A., Aithal, G. P., & Marciani, L. (2021). Effect of Intake of Food Hydrocolloids of Bacterial Origin on the Glycemic Response in Humans: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Nutrients, 13(7), 2407. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13072407