A Food Insecurity Systematic Review: Experience from Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

‘Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life’[3]

- (a)

- What was the prevalence of food insecurity in Malaysia according to studies conducted there?

- (b)

- Who were the high-risk groups of household food insecurity in Malaysia?

- (c)

- What were common instruments used to assess food insecurity in Malaysia?

- (d)

- What were the common contributing factors to rather than of food insecurity among Malaysians?

- (e)

- What were the coping strategies practised by food-insecure households in Malaysia?

- (f)

- What were consequences of food insecurity reported among Malaysians?

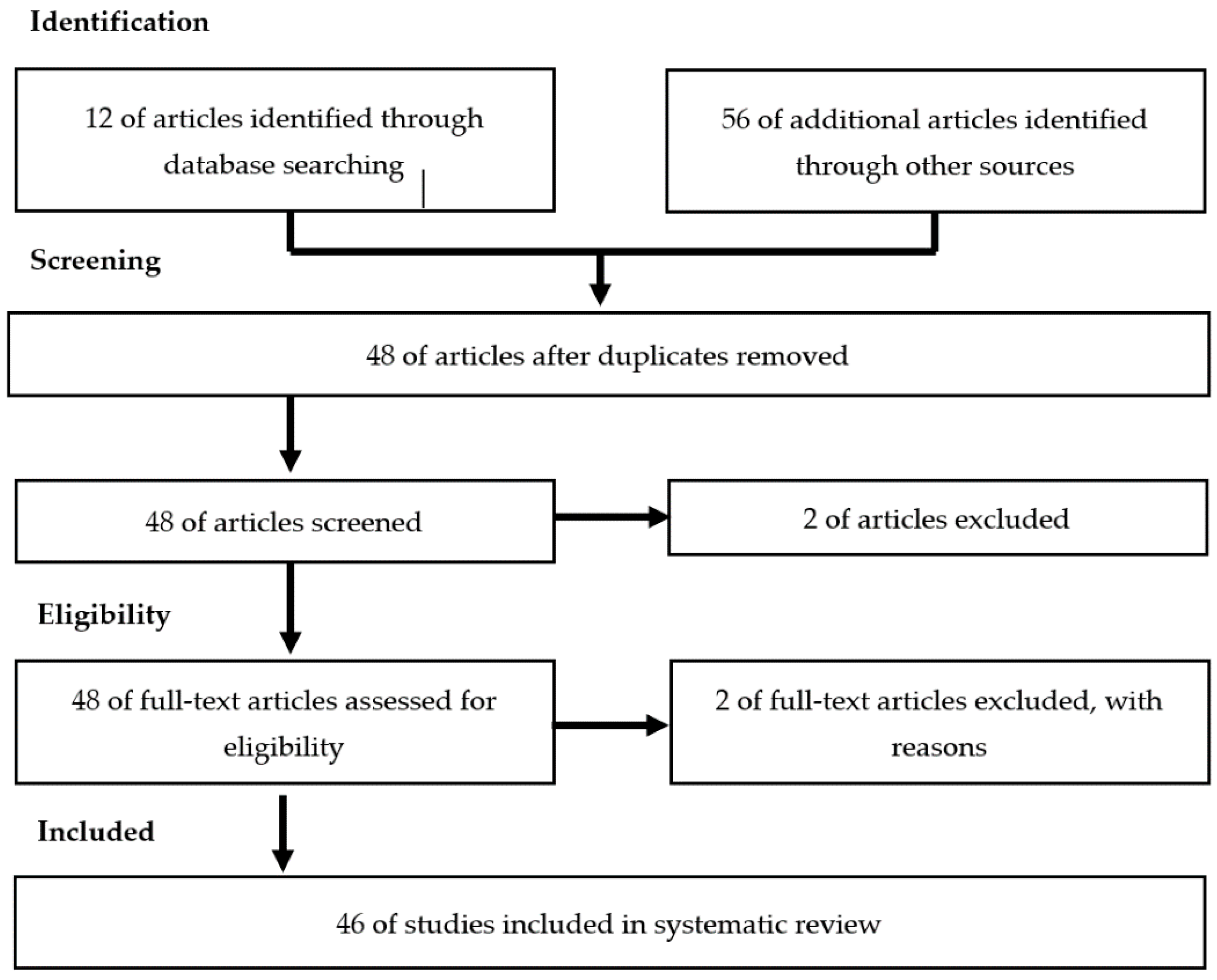

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. The Prevalence of Food Insecurity

3.2. Contributing Factors to Food Insecurity

3.3. Coping Strategies

3.4. Consequences of Food Insecurity

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations of This Study

4.2. Recommendation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoddinott, J. Operationalizing Household Food Security in Development Projects: An Introduction. Technical Guide #1; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Pointing, J.; Maxwell, S. Household Food Security: Concepts and Definitions: An Annotated Bibliography; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2001; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/y1500e/y1500e00.htm (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Food Security Information for Action. Practical Guides. European Commission, FAO Food Security Program; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008; Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/eufao-fsi4dm/doc-training/wkshp_rep_cambodia_1006.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Andersen, S.A. Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J. Nutr. 1990, 120, 1555–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Reports; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/ (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Food and Agriculture Organization; International Fund for Agricultural Development; United Nations Children’s Fund; World Food Programme; World Health Organization. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020; Available online: http://www.fao.org/publications/card/en/c/CA9692EN (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Gregory, C.; Rabbitt, M. Household Food Security in the United STATES in 2016; Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=84972 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Tarasuk, V.; Mitchell, A.; Dachner, N. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2012; Research to Identify Policy Option to Reduce Food Insecurity (PROOF): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; Available online: https://proof.utoronto.ca/resources/proof-annual-reports/annual-report-2012/ (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Dhokarh, R.; Himmelgreen, D.A.; Peng, Y.K.; Segura-Pérez, S.; Hromi-Fiedler, A.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food insecurity is associated with acculturation and social networks in Puerto Rican households. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2011, 43, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, N.S.; Santos, M.O.; Carvalho, C.P.O.; Assunção, M.L.; Ferreira, H.S. Prevalence and factors associated with food insecurity in the context of the economic crisis in Brazil. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2017, 1, e000869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, N.; D’Haese, M.; Vink, N.; Rooyen, C.J.V.; Staelens, L.; Schönfeldt, H.C.; D’Haese, L. Food security in rural areas of Limpopo province, South Africa. Food Secur. 2013, 5, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomayko, E.J.; Mosso, K.L.; Cronin, K.A.; Carmichael, L.; Kim, K.M.; Parker, T.; Yaroch, A.L.; Adams, A.K. Household food insecurity and dietary patterns in rural and urban American Indian families with young children. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, A.; Oyegoke, O. Correlates of food insecurity status of urban households in Ibadan Metropolis, Oyo state, Nigeria. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 2248–2254. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, J.A.; Silva Santos, A.; Oliveira Nascimento, M.A.; Costa Oliveira, J.V.; Silva, D.G.; Mendes-Netto, R.S. Factors associated with food insecurity risk and nutrition in rural settlements of families. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2017, 22, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, M.L.; Mendonça, R.D.; Lopes Filho, J.D.; Lopes, A.C.S. Association between food insecurity and food intake. Nutrition 2018, 54, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, S.; Aguayo, V.M.; Krishna, V.; Nair, R. Household food insecurity and children’s dietary diversity and nutrition in India. Evidence from the comprehensive nutrition survey in Maharashtra. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremedhin, S.; Baye, K.; Bekele, T.; Tharaney, M.; Asrat, Y.; Abebe, Y.; Reta, N. Predictors of dietary diversity in children ages 6 to 23 mo in largely food-insecure area of South Wollo, Ethiopia. Nutrition 2017, 33, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isanaka, S.; Mora-Plazas, M.; Lopez-Arana, S.; Baylin, A.; Villamor, E. Food insecurity is highly prevalent and predicts underweight but not overweight in adults and school children from Bogotá, Colombia. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2747–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, L.L.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Lamp, C.L.; Johns, M.C.; Sutherlin, J.M.; Harwood, J.O. Food security and nutritional outcomes of preschool-age Mexican-American children. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 924–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, M.L.; Holben, D.H.; Holcomb, J.P.; Anderson, H. Food security status and produce intake and behaviors of special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program participants. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1903–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.Y.; Hong, M.J. Food insecurity is associated with dietary intake and body size of Korean children from low-income families in urban areas. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 1598–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas, L.G.; Harley, K.; Fernald, L.C.H.; Guendelman, S.; Mejia, F.; Neufeld, L.M.; Eskenazi, B. Dietary associations of household food insecurity among children of Mexican descent: Results of a binational study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, J.A.; Gans, K.M.; Risica, P.M.; Kirtania, U.; Strolla, L.O.; Fournier, L. How is food insecurity associated with dietary behaviors? An analysis with low income, ethnically diverse participants in a nutrition intervention study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1906–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.W.; Epel, E.S.; Ritchie, L.D.; Crawford, P.B.; Laraia, B.A. Food insecurity is inversely associated with diet quality of lower-income adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 1943–1953.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, G.A.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Yang, Y.J. Health and nutritional status of Korean adults according to age and household food security: Using the data from 2010~2012 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Nutr. Health 2017, 50, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, M.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.; Álvarez, M.C. Household food insecurity associated with stunting and underweight among preschool children in Antioquia, Colombia. Rev. Panam. de Salud Pública 2009, 25, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.C.; Reesor, L.; Alonso, Y.; Eagleton, S.G.; Hughes, S.O. Household food insecurity status and Hispanic immigrant children’s body mass index and adiposity. J. Appl. Res. Child. 2015, 6, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Metallinos-Katsaras, E.; Must, A.; Gorman, K. A longitudinal study of food insecurity on obesity in preschool children. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1949–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speirs, K.E.; Fiese, B.H. The relationship between food insecurity and BMI for preschool children. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, P.; Szeto, K.; Robbins, J.; Stuff, J.; Connell, C.; Gossett, J.; Simpson, P. Child health-related quality of life and household food security. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeer, K.K.; Piperata, B.A. Household food insecurity and child health. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, C.L.; Lofton, K.L.; Yadrick, K.; Rehner, T.A. Children’s experiences of food insecurity can assist in understanding its effect on their well-being. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1683–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Singh, A.; Ram, F. Household food insecurity and nutritional status of children and women in Nepal. Food Nutr. Bull. 2014, 35, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Cheung, H.; Shen, A.; Oo, S.; Tilahun, H.; Cohen, M.J.; Berkowitz, S.A. Food insecurity and body mass index: A longitudinal mixed methods study, Chelsea, Massachusetts, 2009–2013. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2015, 12, E125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ryan-Ibarra, S.; Sanchez-Vaznaugh, E.V.; Leung, C.; Induni, M. The relationship between food insecurity and overweight/obesity differs by birthplace and length of US residence. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, N.C.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Mundo-Rosas, V.; Méndez-Gómez-Humarán, I.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Household food insecurity is associated with anemia in adult Mexican women of reproductive age. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 2066–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronte-Tinkew, J.; Zaslow, M.; Capps, R.; Horowitz, A.; McNamara, M. Food insecurity works through depression, parenting, and infant feeding, to influence overweight and health in toddlers. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Rahman, M.A.; Flora, M.S.; Karim, M.R.; Iqbal Sharif, M.P.; Alam, M.A. Household food security and nutritional status of rural elderly. Bangladesh Med. J. 2011, 40, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, N.J.; Marin-Leon, L. Food insecurity among the elderly: Cross-sectional study with soup kitchen users. Rev. de Nutr. 2013, 26, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharod, J.M.; Croom, J.E.; Sady, C.G. Food insecurity: Its relationship to dietary intake and body weight among Somali refugee women in the United States. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, V.; Tomita, A.; Thela, L.; Mhlongo, M.; Burns, J.K. Food insecurity and risk of depression among refugees and immigrants in South Africa. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, C.; Rosol, R.; Egeland, G.M. The prevalence of food insecurity is high and the diet quality poor in Inuit communities. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, R.; Serebryanikova, I.; Donaldson, K.; Leveritt, M. Student food insecurity: The skeleton in the university closet. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 68, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woerden, I.; Hrushka, D.; Bruening, M. Food insecurity negatively impacts academic performance. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Seligman, H.K.; Meigs, J.B.; Basu, S. Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: A longitudinal cohort study. Am. J. Manag. Care 2018, 24, 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.C. Food insecurity: A nutritional outcome or a predictor variable? J. Nutr. 1991, 121, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, E.C.; Liu, J.; Frongillo, E.A. Poverty, food insecurity and nutritional deprivation in rural China: Implications for children’s literacy achievement. Inter. J. Educ. Dev. 2014, 34, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigel, M.M.; Armijos, R.X.; Racines, M.; Cevallos, W. Food insecurity is associated with undernutrition but not overnutrition in Ecuadorian women from low-income urban neighbourhoods. J. Environ. Public Health 2016, 2016, 8149459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Tarasuk, V. Assessing the relevance of neighbourhood characteristics to the household food security of low-income Toronto families. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habyarimana, J.B. Determinants of household food insecurity in developing countries evidences from a Probit Model for the case of rural households in Rwanda. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2015, 4, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, H.; Sassine, A.B.J.; Seyfert, K.; Nord, M.; Sahyoun, N.R. Prevalence and correlates of food insecurity among Palestinian refugees in Lebanon: Data from a household survey. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e01300724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihab, A.N.; Rohana, A.J.; Wan Manan, M.W.; Suriati, W.N.W.; Zalilah, M.S.; Rusli, A.M. Association between household food insecurity and nutritional outcomes among children in Northeastern of Peninsular Malaysia. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2012, 8, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabli, J. SNAP Participation, Food Security, and Geographical Access to Food; Food and Nutrition Service, Department of Agriculture: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2014. Available online: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/SNAPFS_FoodAccess.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Dwi, W.S.; Sjarkowi, F.; Laila, H. Determinant of household food security status in relation with farming system in south Sumatra (The case of rural community nearby an industrial forest company). Int. J. Chem. Environ. Biol. Sci. 2013, 1, 454–457. [Google Scholar]

- Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) Technical Working Group. Integrated Food Security Phase Classification; IPC Technical Working Group: Johannesburg, South Sudan, 2014; Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/south-sudan/south-sudan-integrated-food-security-phase-classification-snapshot-january-july-0 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Kirimi, L.; Gitau, R.; Olunga, M. Household food security and commercialization among smallholder farmers in Kenya. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference (AAAE), Hammamet, Tunisia, 22–25 September 2013; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/aaae13/161445.html (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Maharjan, K.L.; Khatri-Chhetri, A. Household food security in rural areas of Nepal: Relationship between socio-economic characteristics and food security status. In Proceedings of the International Agricultural Economic Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 12–18 August 2006; Available online: http://ageconsearch.umn.edu/handle/25624 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Belmain, S. Assessment of the Impact of Rodents on Rural Household Food Security and the Development of Ecologically-Based Rodent Management Strategies in Zambézia Province, Mozambique. Project # R7372, ZB0146; Final Technical Report; Department of International Development: London, UK, 2002. Available online: http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/pdf/outputs/cropprotection/r7372_ftr.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Zakari, S.; Ying, L.; Song, B. Factors influencing household food security in West Africa: The case of southern Niger. Sustainability 2014, 6, 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correal, C.; Zuluaga, G.; Madrigal, L.; Caicedo, S.; Plotkin, M. Ingano traditional food and health: Phase 1, 2004–2005. In Indigenous People’s Food Systems: The Many Dimensions of Culture, Diversity, and Environment for Nutrition and Health; Kuhnlein, H.V., Erasmus, B., Spigelski, D., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2009; pp. 83–108. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i0370e/i0370e06.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Schuster, R.C.; Wein, E.E.; Dickson, C.; Chan, H.M. Importance of traditional foods for the food security of two First Nations communities in the Yukon, Canada. Inter. J. Circumpolar Health 2011, 70, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. 1948. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Food: A Fundamental Human Rights. 2001. Available online: http://www.fao.org/FOCUS/E/rightfood/right2.htm (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- World Bank. The World Bank in Malaysia: Overview. 2018. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malaysia/overview (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Syahirah, S.J. Malaysia’s Absolute Poverty Rate at 5.6%—Chief Statistician. The Edge Market. 2020. Available online: https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/malaysias-poverty-rate-rises-56-%E2%80%94-chief-statistician (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Report of Household Income and Basic Amenities Survey 2016. 2017. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=120&bul_id=RUZ5REwveU1ra1hGL21JWVlPRmU2Zz09&menu_id=amVoWU54UTl0a21NWmdhMjFMMWcyZz09 (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Population Distribution and Basic Demographic Characteristics Report 2010. 2011. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/ctheme&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09&bul_id=MDMxdHZjWTk1SjFzTzNkRXYzcVZjdz09 (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA). Indigenous Peoples in Malaysia. Available online: https://www.iwgia.org/en/malaysia.html (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Economic Planning Unit (EPU). Household Income, Poverty, and Household Expenditure. 2021. Available online: http://www.epu.gov.my/en/socio-economic-statistics/household-income-poverty-and-household-expenditure (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN). National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia (1996–2000); Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 1995.

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN). National Action of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia II (2006–2015); Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2006.

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN). National Action of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia III (2006–2015); Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2016.

- Khoo, S.L.; Mohamad Shaharudin, S.; Parthiban, S.G.; Nor Malina, M.; Zhari, H. Urban poverty alleviation strategies from multidimensional and multi-ethnic perspectives: Evidence from Malaysia. Kaji. Malays. 2018, 36, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabius, I.; Ahmad Bashawir, A.G.; Emil, M.; Narmatha, M. Determinants of factors that affecting in Malaysia. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2017, 7, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Muzalwana, A.T.; Noor Khaleeda, A.M.; Sharifah Muhairah, S.; Adzmel, M. Household income and life satisfaction of single mothers in Malaysia. Int. J. Stud. Child. Women Elder. Disabl. 2020, 9, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Aidil Fitri, S.; Charmaine Lim, J.M.; Mohamad Izzuan, M.I. The struggle of Orang Asli in Education: Quality of education. Malays. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Manan, W.M.; Jomo, K.S.; Tan, Z.G. Addressing Malnutrition in Malaysia; Khazanah Research Institute: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, E.A.; Reichenheim, M.E.; de Moraes, C.L.; Antunes, M.M.L.; Salles-Costa, R. Household food insecurity: A systematic review of the measuring instruments used in epidemiological studies. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 18, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tulder, M.; Furlan, A.; Bombardier, C.; Bouter, L.; The Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 2003, 28, 1290–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tool. 2018. Available online: https://joannabriggs.org/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Munn, Z.; Moola, S.; Lisy, K.; Riitano, D.; Tufanaru, C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and incidence data. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Research Service. U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Three-Stage Design, with Screeners; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8271/hh2012.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Radimer, K.L.; Olson, C.M.; Greene, J.C.; Campbell, C.C.; Habicht, J.P. Understanding hunger and developing indicators to assess it in women and children. J. Nutr. Educ. 1992, 24, 36S–44S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Rohana, A.J.; Mohd Nasir, M.T.; Mirnalini, K.; Asnarulkhadi, A.S. Validation of the Malaysian Coping Strategies Instrument to measure household food insecurity in Kelantan, Malaysia. Food Nutr. Bull. 2011, 32, 354–364. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistant Project (FANTA): Washington, DC, USA, 2007; Available online: http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/eufao-fsi4dm/doc-training/hfias.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Chong, S.P.; Geeta, A.; Norhasmah, S. Household food insecurity, diet quality, and weight status among indigenous women (Mah Meri) in Peninsular Malaysia. Nutr. Res. Prac. 2018, 12, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.P.; Geeta, A.; Norhasmah, S. Predictorsof diet quality as measured by Malaysian Healthy Eating Index among aboriginal women (Mah Meri) in Malaysia. Nutrients 2019, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfahilin, T.; Norhasmah, S. Factors and coping strategies related to food insecurity and nutritional status among Orang Asli women in Malaysia. IJPHCS 2015, 2, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Mohd Nasir, M.T.; Asnarulkhadi, A.S. A qualitative study on coping strategies among women from food insecurity households in Selangor and Negeri Sembilan. Malays. J. Nutr. 2010, 16, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ihab, A.N.; Rohana, A.J.; Wan Manan, M.W.; Suriati, W.N.W.; Zalilah, M.S.; Rusli, A.M. Association of household food insecurity and adverse health outcomes among mothers in low-income households: A cross sectional study of a rural sample in Malaysia. Inter. J. Collab. Res. Intern. Med. Public Health 2012, 4, 1971–1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ihab, A.N.; Rohana, A.J.; Wan Manan, M.W.; Suriati, W.N.W.; Zalilah, M.S.; Rusli, A.M. Nutritional outcomes related to household food insecurity among mothers in Rural Malaysia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2013, 31, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Hasnan, A.; Rusidah, S.; Ruhaya, S.; Nur Liana, A.M.; Ahmad Ali, Z.; Wan Azdie, M.A.B.; Tahir, A. Food insecurity situation in Malaysia: Findings from Malaysian Adult Nutrition Survey (MANS) 2014. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 2020, 20, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor Syaza Sofiah, A.; Norhamah, S. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics, household food security status and academic performance among primary school children in North Kinta, Perak, Malaysia. Mal. J. Med. Health Sci. 2020, 16, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Noratikah, M.; Norhasmah, S.; Siti Farhana, M. Socio-demographic factors, food security and mental health status among mothers in Mentakab, Pahang, Malaysia. Mal. J. Med. Health Sci. 2019, 15, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Rohana, A.J. Prevalence, demographic and socio-economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in Kelantan. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2012, 15, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Zalilah, M.S.; Khor, G.L. Indicators and nutritional outcomes of household food insecurity among a sample of rural Malaysian Women. Pak. J. Nutr. 2004, 3, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zalilah, M.S.; Khor, G.L. Obesity and household food insecurity: Evidence from a sample of rural households in Malaysia. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 59, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar]

- Zalilah, M.S.; Khor, G.L. Household food insecurity and coping strategies in a poor rural community in Malaysia. Nutr. Res. Prac. 2008, 2, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ihab, A.N.; Rohana, A.J.; Manan, W.W.; Suriati, W.W.; Zalilah, M.S.; Rusli, A.M. Food expenditure and diet diversity score are predictors of household food insecurity among low income households in rural district of Kelantan Malaysia. Pak. J. Nutr. 2012, 11, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Izwan Syafiq, R.; Asma, A.; Nurzalinda, Z.; Rahijan, A.W.; Siti Nur Afifah, J. Food insecurity among university students at two selected public universities in Malaysia. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2019, 48, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Khairil, A.; Noralanshah, H.; Farah Syafeera, I.; Nazrul, H.I.; Muhammad Ghazali, M. Pilot test on the prevalence of food insecurity among sub-urban university students during holy Ramadan. Pak. J. Nutr. 2015, 14, 457–460. [Google Scholar]

- Nurulhudha, M.J.; Norhasmah, S.; Siti Nur’Asyura, A.; Shamsul Azahari, Z.B. Financial problems associated with food insecurity among public university students in Peninsular Malaysia. Mal. J. Nutr. 2020, 26, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslee, R.; Lee, H.S.; Nurul Izzati, A.H.; Siti Masitah, E. Food insecurity, quality of life, and diet optimization of low income university students in Selangor, Malaysia. J. Gizi Pangan. 2019, 14, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siti Farhana, M.; Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Zuriati, I. Prevalence of food insecurity and associated factors among free-living older persons in Selangor, Malaysia. Malays. J. Nutr. 2018, 24, 349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Nik Aida Adibah, N.A.Z.; Norhasmah, S. Tiada jaminan kedapatan makanan isi rumah di Kampung Pulau Serai, Dungun, Terengganu. Malays. J. Consum. 2013, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, P.P.; Norhasmah, S. Food insecurity among Chinese households in Projek Perumahan Rakyat Air Panas, Setapak, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. IJPHCS 2016, 3, 2289–7577. [Google Scholar]

- Nurzetty Sofia, Z.; Muhammad Hazrin, H.; Nur Hidayah, A.; Wong, Y.H.; Han, W.C.; Suzana, S.; Munirah, I.; Devinder Kaur, A.S. Association between Nutritional Status, Food Insecurity and Frailty among Elderly with Low Income. MJHS 2017, 15, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rohida, S.H.; Suzana, S.; Norhayati, I.; Hanis Mastura, Y. Influence of socio-economic and psychosocial factors on food insecurity and nutritional status of older adults in FELDA settlement in Malaysia. J. Clin. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2017, 8, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhaya, S.; Cheong, S.M.; Mohamad Hasnan, A.; Lalitha, P.; Norlinda, Z.; Siti Adibah, A.H.; Azli, B.S.; Norhasmah, S.; Norsyamlina, C.A.R.; Siti Shahida, A.A.; et al. Factor contributing to food insecurity among older persons in Malaysia: Findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2018. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2020, 20, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siti Farhana, M.; Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Zuriati, I. Does food insecurity contribute towards depression? A cross-sectional study among the urban elderly in Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, F.M.; Faller, E.M.; Lau, X.C.; Gabriel, J.S. Household income, food security and nutritional status of migrant workers in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalilah, M.S.; Tham, B.L. Food security and child nutritional status among Orang Asli (Temuan) households in Hulu Langat, Selangor. Med. J. Malays. 2002, 57, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Law, L.S.; Norhasmah, S.; Gan, W.Y.; Mohd Nasir, M.T. Qualitative study on identification of common coping strategies practised by Indigenous Peoples (Orang Asli) in Peninsular Malaysia during periods of food insecurity. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 2819–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L.S.; Norhasmah, S.; Gan, W.Y.; Siti Nur’Asyura, A.; Mohd Nasir, M.T. The Identification of the Factors Related to Household Food Insecurity among Indigenous People (Orang Asli) in Peninsular Malaysia under Traditional Food Systems. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalilah, M.S.; Ang, M. Assessment of food insecurity among low income households in Kuala Lumpur using the Radimer/Cornell Food Insecurity Instrument—A validation study. Malays. J. Nutr. 2001, 7, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadpour, M.; Sharif, Z.M.; Keysami, M.A. Food insecurity, health and nutritional status among sample of palm-plantation households in Malaysia. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2012, 30, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalilah, M.S.; Norhasmah, S.; Rohana, A.J.; Wong, C.Y.; Yong, H.Y.; Mohd Nasir, M.T.; Mirnalini, K.; Khor, G.L. Food insecurity and the metabolic syndrome among women from low income communities in Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.D.; Siwar, C.; Wahid, A.N.M.; Abdul Talib, B. Food security and low-income households in the Malaysian East Coast Economic Region: An empirical analysis. Rev. Urb. Reg. Dev. Stud. 2015, 28, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Kandiah, M.; Mohd Nasir, M.T.; Asnarulkhadi, A.S. Household food insecurity among urban welfare recipient households in Hulu Langat, Selangor. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 20, 405–420. [Google Scholar]

- Siti Marhana, A.B.; Norhasmah, S. Perbelanjaan dan tiada jaminan kedapatan makanan isi rumah dalam kalangan penerima bantuan pusat urus zakat Pulau Pinang, Bukit Mertajam. Malays. J. Consum. 2012, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, E.E. Evaluating household food insecurity: Applications and insights from rural Malaysia. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2013, 52, 294–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselawati, M.Y.; Wan Azdie, M.A.B.; Aflah, A.; Jamalludin, R.; Zalilah, M.S. Food security status and childhood obesity in Kuantan Pahang. Int. J. Allied Health 2017, 1, 56–71. [Google Scholar]

- Susanti, A.; Norhasmah, S.; Fadilah, M.N.; Siti Farhana, M. Demographic factors, food security, health-related quality of life and body weight status of adolescents in rural area in Mentakab, Pahang, Malaysia. Mal. J. Nutr. 2019, 25, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhasmah, S.; Zuroni, M.J.; Marhana, A.B. Food insecurity among public university students receiving financial assistance in Peninsular Malaysia. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2013, 16, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Siti Marhana, A.B.; Norhasmah, S.; Hsuniyah, A.R. Perbelanjaan dan tiada jaminan kedapatan makanan dalam kalangan mahasiswa yang menerima bantuan kewangan di institusi Pengajian Tinggi Awam. Malays. J. Consum. 2014, 22, 78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nur Atiqah, A.; Norazmir, M.N.; Khairil Anuar, M.I.; Mohd Fahmi, M.; Norazlanshah, H. Food security status: It’s association with inflammatory marker and lipid profile among young adults. Int. Food Res. J. 2015, 22, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Azdie, M.A.B.; Shahidah, I.; Suriati, S.; Rozlin, A.R. Prevalence and factors affecting food insecurity among university students in Pahang, Malaysia. Mal. J. Nutr. 2019, 25, 59–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fadilah, M.N.; Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Zuriati, I. Socio-economic status and food insecurity among the elderly in Panji District, Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia. Malays. J. Consum. Fam. Econ. 2017, 20, 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Law, L.S.; Roselan, B.; Norhasmah, S. Understanding Food Insecurity among Public University Students. Malays. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 12, 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Aznam Yusuf, Z.; Bhattasali, D. Economic Growth and Development in Malaysia: Policy Making and Leadership; Working Paper no. 27; Commission on Growth and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.academia.edu/3175238/Economic_growth_and_development_in_Malaysia_policy_making_and_leadership (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Rusidah, S.; Hasnan, A.; Chong, Z.L.; Ahmad Ali, Z.; Zalilah, M.S.; Wan Azdie, A.B. Household food insecurity in Malaysia: Findings from Malaysian Adults Nutrition Survey. Med. J. Malays. 2015, 70, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Planning Unit (EPU). Tenth Malaysia Plan 2011–2015; Prime Minister’s Department: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2010. Available online: https://www.pmo.gov.my/dokumenattached/RMK/RMK10_Eds.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Department of Orang Asli Development (JAKOA). Strategic Plan for the Orang Asli Development 2011–2015; JAKOA: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2011.

- Loopstra, R.; Tarasuk, V. Severity of household food insecurity is sensitive to change in household income and employment status among low-income families. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1316–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigel, M.; Armijos, R.X.; Racines, M.; Cevallos, W.; Castro, N.P. Association of household food insecurity with the mental and physical health of low-income urban Ecuadorian women with children. J. Environ. Public Health 2016, 2016, 5256084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.P. Accessibility of summer meals and food insecurity of low-income households with children. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2079–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmin, B.; Martin, J.C.; Yanling, G.; Piort, W. The association of household food security, household characteristics and school environment with obesity status among off-reserve First Nations and Métis children and youth in Canada: Results from the 2012 Aboriginal Peoples Survey. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. 2017, 37, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Willows, N.; Veugelers, P.; Raine, K.; Kuhle, S. Associations between household food insecurity and health outcomes in the Aboriginal population (excluding reserves). Health Rep. 2011, 22, 15. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2011002/article/11435-eng.htm (accessed on 6 December 2020). [PubMed]

- Temple, J.B.; Russell, J. Food insecurity among older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Int. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimberlin, C.L.; Winterstein, A.G. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments use in research. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2008, 65, 2276–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micevski, D.A.; Thornton, L.E.; Brockington, S. Food insecurity among university students in Victoria: A pilot study. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 71, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne-Sturges, D.C.; Tjaden, A.; Caldeira, K.M.; Vincent, K.B.; Arria, A.M. Student hunger on campus: Food insecurity among college students and implications for academic institutions. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entza, M.; Slaterb, J.; Desmaraisc, A.A. Student food insecurity at the University of Manitoba. Can. Food Stud. 2017, 4, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharani, A.R.; Puzziawati, A.G.; Noorizam, D.; Zulkiifli, A.G.H.; Siti Noorul Ain, N.A.; Sharifah Norhuda, S.W.; Mohd Rizal, R. Malaysia’s aging population trends. In Regional Conference on Science, Technology and Social Sciences (RCSTSS 2014), Proceedings of the RCSTSS 2014, Cameron Highlands, Pahang, Malaysia, 23–25 November 2014; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliak, J.P.; Gundersen, C. The State of Senior Hunger in America 2016: An Annual Report; Feeding America: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/research/senior-hunger-research/state-of-senior-hunger-2016.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Russell, J.; Flood, V.; Yeatman, H.; Mitchell, P. Prevalence and risk factors of food insecurity among a cohort of older Australians. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, H.; Meseri, R.; Sahin, S.; Ucku, R. Prevalence of food insecurity and malnutrition, factors related to malnutrition in the elderly: A community-based cross-sectional study from Turkey. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2013, 4, 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.; Fafard St-Germain, A.A.; Mitchell, A. Geographic and socio-demographic predictors of household food insecurity in Canada, 2011–2012. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willows, N.D.; Veugelers, P.; Raine, K.; Kuhle, S. Prevalence and sociodemographic risk factors related to household food security in Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 12, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neter, J.E.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Visser, M.; Brouwer, I.A. Food insecurity among Dutch food bank recipients: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2013, 4, e004657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, S.G.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Nunes, C.; Santos, O.; Gregório, M.J.; de Sousa, R.D.; Dias, S.; Canhão, H. Food insecurity in older adults: Results from the epidemiology of chronic diseases cohort study 3. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, J.; Morrison, K.; Rosenberg, M. Prevalence and predictors of food insecurity among older people in Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Decent Rural Employment for Food Security: A Case for Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i2750e/i2750e00.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Olayemi, A.O. Effects of Family Size on Household Food Security in Osun State, Nigeria. Asian J. Agric. Dev. 2012, 2, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Jih, J.; Stijacic-Cenzer, I.; Seligman, H.K.; Boscardin, W.J.; Nguyen, T.T.; Ritchie, C.S. Chronic disease burden predicts food insecurity among older adults. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhaime, G.; Godmaire, A. The conditions of sustainable food security: An integrated conceptual framework. In Sustainable Food Security in the Arctic: State of Knowledge; Duhaime, G., Ed.; University of Alberta, CCI Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2002; p. 32. Available online: https://journalindigenouswellbeing.com/volume-1-2-winter-2003/the-conditions-of-sustainable-food-security-an-integrated-conceptual-framework/ (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Chilton, M.; Rabinowich, J.; Breen, A.; Mouzon, S. When the system fails: Individual and household coping strategies related to child hunger. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Research Gaps and Opportunities on the Causes and Consequences of Child Hunger, Committee on National Statistics and Food and Nutrition Board, Washington, DC, USA, 8–9 April 2013; Available online: https://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/dbasse_084305.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Kisi, M.A.; Tamiru, D.; Teshome, M.S.; Tamiru, M.; Feyissa, G.T. Household food insecurity and coping strategies among pensioners in Jimma Town, south west Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, D.R. Household food security and coping strategies: Vulnerabilities and capabilities in rural communities. IJSRP 2014, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rukundo, P.M.; Oshaug, A.; Andreassen, B.A.; Kikafunda, J. Food variety consumption and household food insecurity coping strategies after the 2010 landslide disaster—The case of Uganda. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 3197–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabuza, M.L.; Ortmann, G.F.; Wale, E. Frequency and extent of employing food insecurity coping strategies among rural households: Determinants and implications for policy using evidence from Swaziland. Food Secur. 2016, 8, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Oh, K. Household food insecurity and dietary intake in Korea: Results from the 2012 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakitto, M.; Asano, K.; Chi, I.; Yoon, J. Dietary intake of adolescents from food insecure households: Analysis of data from the 6th (2013–2015) Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2017, 11, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbadi, P.; Urke, H.B.; Mittelmark, M.B. Household food insecurity and adequacy of child diet in the food insecure region north in Ghana. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, M.P.; Martini, L.H.; Çayir, E.; Hartline-Grafton, H.L.; Meade, R.L. Severity of household food insecurity is positively associated with mental disorders among children and adolescents in the United States. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2019–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, J.M.; Nyakato, V.N.; Kakuhikire, B.; Tsai, A.C. Food insecurity, social networks and symptoms of depression among men and women in rural Uganda: A cross-sectional, population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchior, M.; Caspi, A.; Howard, L.M.; Ambler, A.P.; Bolton, H.; Mountain, N.; Moffitt, T.E. Mental health context of food insecurity: A representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e564–e572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, J.; Caillavet, F.; Lhuissier, A.; Chauvin, P. Food insecurity, a determinant of obesity? An analysis from a population-based survey in the Paris Metropolitan area, 2010. Obes. Facts 2014, 7, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keino, S.; Plasqui, G.; van den Borne, B. Household food insecurity access: A predictor of overweight and underweight among Kenyan women. Agric. Food Secur. 2014, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienaar, M.; van Rooyen, F.C.; Walsh, C.M. Household food insecurity and HIV status in rural and urban communities in the Free State province, South Africa. SAHARA J. 2017, 14, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heflin, C.M.; Altman, C.E.; Rodriguez, L.L. Food insecurity and disabilities in the United States. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chilton, M.; Black, M.M.; Berkowitz, C.; Casey, P.H.; Cook, J.; Cutts, D.; Jacobs, R.R.; Heeren, T.; de Cuba, S.E.; Coleman, S.; et al. Food insecurity and risk of poor health among US-born children of immigrants. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Checklist |

|---|---|

| 1 | Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? |

| 2 | Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? |

| 3 | Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? |

| 4 | Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? |

| 5 | Were confounding factors identified? |

| 6 | Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? |

| 7 | Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? |

| 8 | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? |

| No. | Checklist |

|---|---|

| 1 | Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? |

| 2 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? |

| 3 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? |

| 4 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? |

| 5 | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? |

| 6 | Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? |

| 7 | Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice- versa, addressed? |

| 8 | Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? |

| 9 | Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? |

| 10 | Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? |

| No. | Authors | Year | Study Design | Respondents (Target Groups) | Study Location | Instrument | Prevalence | Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orang Asli (Indigenous Peoples) | ||||||||

| 1. | Zalilah, M.S. and Tham, B.L. [116] | 2002 | Cross-sectional study | n = 64 Women Orang Asli (Indigenous Peoples) (information on household food insecurity) and child (weight and height) | Hulu Langat District of Selangor, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 81.2% food insecurity (20.3% household food insecurity 32.8% individual food insecurity 28.1% child hunger) | 2/8 |

| 2. | Nurfahilin, T. and Norhasmah, S. [92] | 2015 | Cross-sectional study | n = 92 Women Orang Asli | Gombak District of Selangor, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 88% food insecurity (48.9% household food insecurity 21.7% individuals food insecurity 17.4% child hunger) | 4/8 |

| 3. | Chong, S.P., Geeta, A. and Norhasmah, S. [90] | 2018 | Cross-sectional study | n = 222 Orang Asli (Indigenous) Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating Non-vegetarian No chronic diseases No changes in food habits in past six months | Kuala Langat District of Selangor, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 82.9% food insecurity (29.3% household food insecurity, 23.4% individual food insecurity, 30.2% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 4. | Chong, S.P., Geeta, A. and Norhasmah, S. [91] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | n = 222 Orang Asli (Indigenous) Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating Non-vegetarian No chronic diseases No changes in food habits in past six months to reduce weight | Kuala Langat District of Selangor, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 82.9% food insecurity (29.3% household food insecurity, 23.4% individual food insecurity, 30.2% child hunger) | 8/8 |

| 5. | Law, L.S., Norhasmah, S., Gan, W.Y. and Mohd Nasir, M.T. [117] | 2018a | Case study (qualitative study) | In-depth interviews 61 women (Senoi, Proto-Malay and Negrito) FGD 19 women proto Malay | Perak, Selangor, and Pahang, Malaysia | - | - | 8/10 |

| 6. | Law, L.S., Norhasmah, S., Gan, W.Y., Siti’Asyura, A., and Mohd Nasir, M.T. [118] | 2018b | Case study (qualitative study) | n = 61 Orang Asli women Food aid-recipient household Non-pregnant and non-lactating | Perak, Selangor, and Pahang, Malaysia | - | - | 8/10 |

| Low-income households/welfare-recipient households | ||||||||

| 7. | Zalilah, M.S. and Ang, M. [119] | 2001 | Cross-sectional study | n = 137 Women (information on household food insecurity) and child (weight and height) | Kuala Lumpur | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 65.7% food insecurity (27.7% household food insecurity 10.9% individual food insecurity 27.0% child hunger) | 5/8 |

| 8. | Zalilah, M.S. and Khor, G.L. [100] | 2004 | Cross-sectional study | n = 200 Women of poor households in a rural community in Malaysia | Sabak Bernam District of Selangor state | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 58.0% food insecurity (14% household food insecurity 9.5% individual food insecurity 34.5% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 9. | Zalilah, M.S. and Khor, G.L. [101] | 2005 | Cross-sectional study | n = 200 Women of poor households in a rural community in Malaysia | Sabak Bernam District of Selangor State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 58.0% food insecurity (14.0% household food insecurity 9.5% individual food insecurity 34.5% child hunger) | 6/8 |

| 10. | Zalilah, M.S. and Khor, G.L. [102] | 2008 | Cross-sectional study | n = 200 Women of poor households in a rural community in Malaysia | Sabak Bernam District of Selangor State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 58.0% food insecurity (14.0% household food insecurity 9.5% individual food insecurity 34.5% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 11. | Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., Mirnalini, K., Mohd Nasir, M.T and Asnarulkhadi, A.S. [88] | 2011 | Cross-sectional study | n = 301 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating, living in rural and urban areas | Tumpat and Kota Bharu Districts of Kelantan, State | Malaysian Coping Strategy Instrument (MCSI) | 68.1% food insecurity (33.9% moderately food insecurity, 34.2% severely food insecurity) | 6/8 |

| 12. | Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S. and Rohana, A.J [99] | 2012a | Cross-sectional study | n = 301 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating, living in rural and urban areas | Tumpat and Kota Bharu Districts of Kelantan, State | Malaysian Coping Strategy Instrument (MCSI) | 68.1% food insecurity (33.9% moderately food insecurity, 34.2% severely food insecurity) | 6/8 |

| 13. | Mohamadpour, M., Zalilah M.S., Keysami M.A. [120] | 2012 | Cross-sectional study | n = 169 Palm plantation women Non-pregnant and non-lactating | Nilai, Negeri Sembilan State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 85.2% food insecurity (24.9% household food insecurity, 19.5% individual food insecurity 40.8% child hunger) | 6/8 |

| 14. | Nik Aida Adibah, N.A.A. and Norhasmah S. [109] | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | n = 80 Women | Kampung Pulau Serai, Dungun District of Terengganu, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 93.75% food insecurity (51.25% household food insecurity 23.75% individuals food insecurity 18.75% child hunger) | 3/8 |

| 15. | Zalilah, M.S., Norhasmah, S., Rohana, A.J., Wong, C.Y, Yong, H.Y., Mohd Nasir, M.T., Mirnalini, K., and Khor, G.L. [121] | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | n = 625 Women Low-income communities | 3 states of Peninsular Malaysia (Selangor, Negeri Sembilan and Kelantan) | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 78.4% food insecurity (26.7% household food insecurity 25.3% individual food insecurity 26.4% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 16. | Alam, M.D., Siwar, C., Wahid, A.N.M. and Abdul Talib, B. [122] | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | n = 460 Households from urban and rural areas East Coast Economic Region (ECER) (e-kasih database) | Kelantan, Terengganu Pahang States | United States Agency for International Development Household Food Insecurity Access | 47.2% food insecurity (23.3% mildly food insecurity 14.3% moderately food insecurity 9.6% are severely food insecurity) | 1/8 |

| 17. | Yong, P.P. and Norhasmah, S. [110] | 2016 | Cross-sectional study | n = 109 Chinese women aged between 30 and 55 years old | Program Perumahan Rakyat (PPR) Kuala Lumpur | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 50.6% food insecurity (18.5% household insecurity 14.8% individual insecurity 17.3% child hunger) | 1/8 |

| 18. | Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., Mirnalini, K., Mohd Nasir, M.T. and Asnarulkhadi, A.S. [123] | 2012b | Cross-sectional study | n = 103 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households | Hulu Langat District of Selangor, State | Malaysian Coping Strategy Instrument (MCSI) | 73.8% food insecurity (39.8% moderate food insecurity, 34.0% severely food security) | 4/8 |

| 19. | Siti Marhana, A.B. and Norhasmah, S. [124] | 2012 | Cross-sectional Study | n = 80 Women and men Zakat recipients | Bukit Martajam, Pulau Pinang, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 100.0% food insecurity (5.0% household food insecurity, 30.0% individual food insecurity 65.0% child hunger) | 3/8 |

| 20. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S., and Mohamed Rusli, A. [54] | 2012a | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households | Bachok District of Kelantan, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 83.9% food insecurity (29.6% household food insecurity 19.3% individuals food insecurity 35.0% child hunger) | 6/8 |

| 21. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S., and Mohamed Rusli, A. [103] | 2012b | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households | Bachok District of Kelantan, State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument (PJN) | 83.9% food insecurity (29.6% household food insecurity 19.3% individuals food insecurity 35.0% child hunger) | 6/8 |

| 22. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S., and Mohamed Rusli, A. [94] | 2012c | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households | Bachok District of Kelantan State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 83.9% food insecurity (29.6% household food insecurity 19.3% individuals food insecurity 35.0% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 23. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S., and Mohamed Rusli, A. [95] | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households | Bachok District of, Kelantan State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 83.9% food insecurity (29.6% household food insecurity 19.3% individuals food insecurity 35.0% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 24. | Cooper, E.E. [125] | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | n = 70 Households Children (n = 104) aged between 6 months and 6 years old Malay fishing villages | Sematan subdistrict of Lundu at the southwest coast of Sarawak | Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) | 64.3% food insecurity (10.0% mildly food insecurity 25.7% moderately food insecurity 28.6% severely food security) | 2/8 |

| 25. | Roselawati, M.Y., Wan Azdie, M.A.B., Aflah, A., Jamalludin, R., and Zalilah, M.S. [126] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | n = 128 Malay women with their children Age 21 to 59 years olds | Kuantan District of Pahang State | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 77.0% food insecurity (52.0% house old food insecurity, 9.0% individual food insecurity 16.0% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 26. | Mohamad Hasnan, A., Rusidah, S., Ruhaya, S., Nur Liana, A.M., Ahmad Ali, Z., Wan Azdie, A.B., and Tahir, A. [96] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | n = 2962 Adults | National representative sample in Malaysia | Six items adapted from USDA instruments (United States Department of Agriculture) | Quantity insufficiency: 25.0% Variety insufficiency: 25.5% Reduced size of meal: 21.9% Skipped meal: 15.2% Rely on cheap food and affordable food: 23.7% Could not afford to feed their children with various food: 20.8% | 4/8 |

| 27. | Nor Syaza Sofiah, A.; Norhasmah, S. [97] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | n = 140 Adults | Two national primary schools | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 80.7% food insecurity (26.4% household food insecurity, 27.9% individual food insecurity, 26.4% child hunger) | 4/8 |

| 28. | Noratikah, Norhasmah and Siti Farhana [98] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | n = 129 Mothers aged 20 to 59 years | Low household income | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 55.8% food insecurity (7.0% household food insecurity, 30.2% individual food insecurity, 18.6% child hunger) | 7/8 |

| 29. | Susanti, A., Norhasmah, S., Fadilah, M.N., and Siti Farhana, M. [127] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | n = 160 Households that comprised pairs of mothers and children aged 13–17 years | Mentakab, Temerloh district, Pahang | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 48.8% food insecurity (20.0% household food insecurity, 13.8% individual food insecurity, 15.0% child hunger) | 8/8 |

| 30. | Norhasmah, S.; Zalilah, M.S.; Mohd Nasir, M.T.; Asnarulkhadi, A.S. [93] | 2010 | Case study (qualitative study) | n = 57 20–50-year-old women | Selangor and Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia | - | - | 7/10 |

| University students | ||||||||

| 31. | Norhasmah, S., Zuroni, M.J. and Siti Marhana, A.B. [128] | 2013 | Cross-sectional study | n = 484 Undergraduate Public University students | Peninsular Malaysia | USDA instruments (United States Department of Agriculture) | 67.1% food insecurity (44.4% low food insecurity, 22.7% very low food insecurity) | 1/8 |

| 32. | Siti Marhana, A.B., Norhasmah, S. and Husniyah, A.R [129] | 2014 | Cross-sectional study | 484 Public Undergraduate Public University students | Peninsular Malaysia | USDA instruments (United States Department of Agriculture) | 67.1% food insecurity (44.4% low food insecurity, 22.7% very low food insecurity) | 2/8 |

| 33. | Nur Atiqah, A., Norazmir, M.N, Khairil Anuar, M.I., Mohd Fahmi, M. and Norazlanshah, H. [130] | 2015 | Cross-sectional study | n = 124 University students | Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) Puncak Alam Selangor, State | Adults Food Security Survey Module (AFSSM) | 43.5% food insecurity | 5/8 |

| 34. | Izwan Syafiq, R.; Asma, A.; Nurzalinda, Z.; Rahijan, A.W.; Siti Nur Afifah, J. [104] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | n = 96 University students | Two selected public universities in Terengganu | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity instrument | 22% food insecurity (14% low food security, 8% very low food security) | 1/8 |

| 35. | Khairil, A.; Noralanshah, H.; Farah Syafeera, I.; Nazrul, H.I.; Muhammad Ghazali, M. [105] | 2015 | Cross-sectional study | n = 30 University students | Kolej Jasmine, UiTM Puncak Perdana, Shah Alam, Malaysia | Adults Food Security Survey Module (AFSSM) | 70% food insecurity (37% low food security, 30% very low food security) | 3/8 |

| 36. | Nurulhudha, Norhasmah, Siti Nur’ Asyura, and Shamsul Azahari [106] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | 427 Undergraduate Public University students | Universiti Utara Malaysia, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Universiti Malaysia Pahang and Universiti Teknologi Malaysia | Adults Food Security Survey Module (AFSSM) | 60.9% food insecurity (39.3% low food security, 21.6% very low food security) | 7/8 |

| 37. | Roslee, R.; Lee, H.S.; Nurul Izzati, A.H.; Siti Masitah, E. [107] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | n = 108 Low-income university students | Selangor, Malaysia | USDA Household Food Security Survey Module 2012 (Six Item Short Form) | 69.4% food insecurity (50.5% low food security, 29.3% very low food security) | 2/8 |

| 38. | Wan Azdie, M.A.B., Shahidah, I., Suriati, S., and Rozlin, A.R. [131] | 2019 | Cross-sectional study | n = 307 Students from six faculties of the International Islamic University Malaysia | Kuantan, Pahang | Adults Food Security Survey Module (AFSSM) | 54.4% food insecurity (32.9% low food security, 21.5% very low food security) | 3/8 |

| 39. | Law, L.S., Roselan, B. and Norhasmah, S. [117] | 2015 | In-depth interview (qualitative research) | 4 informants University students | Selangor, Malaysia | - | - | 5/10 |

| Elderly population | ||||||||

| 40. | Fadilah, M.N., Norhasmah, S., Zalilah M.S. and Zuriati I. [132] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | n = 227 Elderly aged 60 and over | Mukim Panji, Kota Bharu District of Kelantan State | USDA Household Food Security Survey Module 2012 (Six Item Short Form) | 22.9% food insecurity (15.4% low food security, 7.5% very low food security) | 4/8 |

| 41. | Nurzetty Sofia, Z., Muhammmad Hazrin, H., Nur Hidayah, A., Wong, Y.H., Han, W.C., Suzana, S., Munirah, I. and Devinder Kaur, A.S. [111] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | n = 72 Elderly aged 60 years Able to communicate total household income lower than or equal to RM3000 per month Do not suffer from terminal illness, dementia and mental illness | Urban poor residential area in Klang Valley of Malaysia (i.e., Kampung Medan, Petaling Jaya) | Radimer/Cornell Hunger and Food Insecurity Instrument | 6.9% food insecurity | 5/8 |

| 42. | Rohida, S.H., Suzana, S., Norhayati, I. and Hanis Mastura, Y. [112] | 2017 | Cross-sectional study | n = 289 Older adults aged 60 years and over | Older adults from FELDA Land Development Authority (FELDA)—Northern Region of Malaysia | Food Security Tool For Elderly | 27.7% food insecurity 22.4% food insecurity for men 29.0% food insecurity for women | 3/8 |

| 43. | Siti Farhana, M., Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., and Zuriati, I. [114] | 2018 | Cross-sectional study | n = 220 Older adults aged 60 to 87 years | Two randomly subdistricts (Petaling II and Damansara) in Petaling district | Six-item Short Form of Food Security Status | 19.5% food insecurity 18.2% low food security 1.3% low food security | 4/8 |

| 44. | Ruhaya et al. [113] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | n = 3977 Older adults ≥ 60 years old | National representative sample in Malaysia | USDA Household Food Security Survey Module 2012 and USDA Household Food Security Survey Module 2012 (Six Item Short Form) | 10.4% food insecurity | 7/8 |

| 45. | Siti Farhana, M., Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., Zuriati, I. [114] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | n = 220 Elderly people aged 60 years and over | Petaling district, Selangor, Malaysia | USDA Household Food Security Survey Module 2012 (Six Item Short Form) | 19.5% food insecurity | 6/8 |

| Migrant worker | ||||||||

| 46. | Chan, F.M., Faller, E.M., Lau, X.C., and Gabriel, J.S. [115] | 2020 | Cross-sectional study | n = 125 Documented migrant workers from five selected countries | Klang Valley, Selangor | Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) | 57.6% food insecurity (24.8% mildly, 29.6% moderately, 3.2% severely) | 4/8 |

| No. | Authors | Study Design | Respondents (Target Groups) | Risk Factors for Food Insecurity | Health and Nutritional Outcomes of Food Insecurity | Categories of Coping Strategies | Coping Strategies (Top Five for Each Coping Strategy Group) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orang Asli | |||||||

| 1. | Zalilah, M.S. and Tham, B.L. [116] (2002) | Cross-sectional study | n = 64 Women Orang Asli (Indigenous Peoples) |

| Among children

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 2. | Nurfahilin, T. and Norhasmah, S. [92] (2005) | Cross-sectional study | n = 92 Women Orang Asli |

| Among orang Asli women

| Food-related coping strategies |

|

| Non-food-related coping strategies |

| ||||||

| 3. | Chong, S.P., Geeta, A. and Norhasmah, S. [90] (2008) | Cross-sectional study | n = 222 Orang Asli (Indigenous) Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating Non-vegetarian No chronic diseases No changes in food habits in past six months |

| Among orang Asli women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 4. | Chong, S.P., Geeta, A. and Norhasmah, S. [91] (2019) | Cross-sectional study | n = 222 Orang Asli (Indigenous) Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating Non-vegetarian No chronic diseases No changes in food habits in past six months | -NA- | Among orang Asli women Food security status appeared to be a predictor for diet quality | -NA- | -NA- |

| 5. | Law, L.S, Norhasmah, S., Gan, W.Y. and Mohd Nasir, M.T. [117] (2018a) | Case study (qualitative study) | In-depth interviews 61 women (Senoi, Proto-Malay and Negrito) FGD 19 women proto Malay | -NA- | -NA- | Identified 21 coping strategies and divided into two themes | |

| Food consumption (four themes) | |||||||

| Dietary changes (two subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Diversification of food sources (nine subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Decreasing the number of people (two subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Food rationing (five subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Financial management (three themes) | |||||||

| Increasing household income (two subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Reducing expenses for schooling children (three subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Reducing expenses on daily necessities (two subthemes) |

| ||||||

| 6. | Law, L.S., Norhasmah, S., Gan, W.Y., Siti’Asyura, A., and Mohd Nasir, M.T. [118] (2018b) | Case study | n = 61 Orang Asli women Food aid-recipient household Non-pregnant and non-lactating |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| Low-income households/welfare-recipient households/mothers | |||||||

| 7. | Zalilah, M.S. and Ang, M. [119] (2001) | Cross-sectional study | n = 137 Women (information on household food insecurity) and child (weight and height) |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 8. | Zalilah, M.S. and Khor, G.L. [100] (2004) | Cross-sectional study | n = 200 Women of poor households in a rural community in Malaysia |

| Among women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 9. | Zalilah, M.S. and Khor, G.L. [101] (2005) | Cross-sectional study | n = 200 Women of poor households in a rural community in Malaysia |

| Among women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 10. | Zalilah, M.S. and Khor, G.L. [102] (2008) | Cross-sectional study | n = 200 Women of poor households in a rural community in Malaysia |

| Food-related coping strategies |

| |

| Income/expenditure-related coping strategies |

| ||||||

| 11. | Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., Mirnalini, K., Mohd Nasir, M.T and Asnarulkhadi, A.S. [88] (2011) | Cross-sectional study | n = 301 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating, living in rural and urban areas |

| Among women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 12. | Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., and Rohana, A.J. [99] (2012a) | Cross-sectional study | n = 301 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating, living in rural and urban areas |

| Among women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 13. | Mohamadpour, M., Zalilah, M.S., and Keysami, M.A. [120] (2012) | Cross-sectional study | n = 169 Palm plantation women Non-pregnant and non-lactating |

| Among women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 14. | Nik Aida Adibah, N.A.A. and Norhasmah, S. [109] (2013) | Cross-sectional study | n = 80 Women |

| -NA- | Food-related coping strategies |

|

| Non-food-related coping strategies |

| ||||||

| 15. | Zalilah, M.S., Norhasmah, S., Rohana, A.J., Wong, C.Y, Yong, H.Y., Mohd Nasir, M.T., Mirnalini, K., and Khor, G.L. [121] (2014) | Cross-sectional study | n = 625 Women Low-income communities |

| Among women

Elevated plasma glucose Cholesterol LDL cholesterol Metabolic syndrome | Food-related coping strategies (four themes) | |

| Food stretching (two subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Food rationing (five subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Food seeking (two subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Food anxiety (one sutheme) |

| ||||||

| Non-food-related coping strategies (four themes) | |||||||

| Cloth purchasing behaviours (three suthemes) |

| ||||||

| Reduce school-going children’s expenditure (two subthemes) |

| ||||||

| Delay the payment of bills (three suthemes) |

| ||||||

| Adjust lifestyle (8 subthemes) |

| ||||||

| 16. | Cooper, E.E. [125] (2013) | Cross-sectional study | n = 70 Households children (n = 104) aged between 6 months and 6 years old Malay fishing villages | -NA- | -NA- | Food-related coping strategies | Unwanted food consumption (e.g., uncooked blocks of ramen, diluted rice porridge and scavenged cassava leaves) (e.g., ‘If we eat, we eat. If not, there is nothing to be done. You keep quiet’). |

| Women’s alternative income strategies |

| ||||||

| 17. | Alam, M.D., Siwar, C., Wahid, A.N.M. and Abdul Talib, B. [122] (2016) | Cross-sectional study | n = 460 Households from urban and rural areas East Coast Economic Region (ECER) (e-kasih database) |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 18. | Yong, P.P. and Norhasmah, S. [110] (2016) | Cross-sectional study | n = 109 Chinese women aged between 30 and 55 years old |

| Among women

| Food-related coping strategies |

|

| Non-food-related coping strategies |

| ||||||

| 19. | Roselawati, M.Y., Wan Azdie, M.A.B., Aflah, A., Jamalludin, R., and Zalilah, M.S. [126] (2017) | Cross-sectional study | n = 128 Malay women with their children Aged 21 to 59 years olds |

| Among children The proportion of overweight/obesity among children from food secure households was lower (48.3%) than from food-insecure households were (60.6%) However, no significant different between childhood overweight/obesity and food security status | -NA- | -NA- |

| 20. | Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S, Mirnalini, K., Mohd Nasir, M.T and Asnarulkhadi, A.S. [123] (2012b) | Cross-sectional study | n = 103 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 21. | Siti Marhana, A.B. and Norhasmah, S. [124] (2012) | Cross-sectional Study | n = 80 Women and men Zakat recipients |

| -NA- | Food-related coping strategies |

|

| Non-food-related coping strategies |

| ||||||

| 22. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S. and Mohamed Rusli, A. [103](2012b) | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non- pregnant Non-lactating welfare-recipient households |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 23. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S., and Mohamed Rusli, A. [95] (2013) | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households |

| Among women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 24. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S., and Mohamed Rusli, A. [54] (2012a) | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating Welfare-recipient households |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 25. | Noratikah, Norhasmah and Siti Farhana [98] (2019) | Cross-sectional study | n = 129 Mothers aged 20 to 59 years |

| Among women

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 26. | Mohamad Hasnah, A., Rusidah, S., Ruhaya, S., Nur Liana, A.M., Ahmad Ali, Z., Wan Azdie, A.B., and Tahir, A. [96] (2020) | Cross-sectional study | n = 2962 Adults |

| |||

| 27. | Susanti, A., Norhasmah, S., Fadilah, M.N., and Siti Farhana, M. [127] (2019) | Cross-sectional study | n-160 Households that comprised pairs of mothers and children aged 13–17 years |

| Among adolescents

BMI | -NA- | -NA- |

| 28. | Ihab, A.N., Rohana, A.J., Wan Manan, W.M., Wan Suriati, W.N., Zalilah, M.S., and Mohamed Rusli, A. [94] (2012c) | Cross-sectional study | n = 223 Women Non-pregnant and non-lactating welfare-recipient households | Among women

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| University students | |||||||

| 29. | Norhasmah, S., Zuroni, M.J. and Siti Marhana, A.B. [128] (2013) | Cross-sectional study | n = 484 Undergraduate Public University students |

| -NA- | Food-related coping strategies |

|

| Non-food-related coping strategies |

| ||||||

| 30. | Law, L.S. Roselan, B. and Norhasmah, S. [117] (2015) | Inidepth interview (qualitative research) | 4 informants University students |

| Among university students

| Food-related coping strategies |

|

| 31. | Siti Marhana, A.B., Norhasmah, S. and Husniyah, A.R. [129] (2014) | Cross-sectional study | 484 Public Undergraduate Public University students |

| -NA- | Food coping strategies |

|

| Non-food-related coping strategies |

| ||||||

| 32. | Nurulhudha, Norhasmah, Siti Nur’ Asyura, and Shamsul Azahari [106] (2020) | Cross-sectional study | 427 Undergraduate Public University students |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 33. | Wan Azdie, M.A.B., Shahidah, I., Suriati, S., and Rozlin, A.R. [131] (2019) | Cross-sectional study | n = 307 Students from six faculties of the International Islamic University Malaysia |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 34. | Nur Atiqah, A., Norazmir, M.N, Khairil Anuar, M.I., Mohd Fahmi, M. and Norazlanshah, H. [130] (2015) | Cross-sectional study | 124 university students (18 to 25) years old | Among university students

| s-NA- | -NA- | |

| Elderly population | |||||||

| 35. | Fadilah, M.N, Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S. and Zuriati, I. [132] (2017) | Cross-sectional study | n = 227 Elderly aged 60 and over |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 36. | Siti Farhana, M., Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., and Zuriati, I. [108] (2018) | Cross-sectional study | n = 220 Older adults aged 60 to 87 years | Univariate analysis: Significant associations between food insecurity with:

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 37. | Ruhaya et al. [113] (2020) | Cross-sectional study | n = 3977 Older adults ≥ 60 years old |

| -NA- | -NA- | -NA- |

| 38. | Nurzetty Sofia Z, Muhammmad Hazrin H, Nur Hidayah A., Wong Y. H., Han W. C., Suzana S., Munirah I. and Devinder Kaur A. S. [111] (2017) | Cross-sectional study | n = 72 Elderly aged 60 years Able to communicate Household income ≤ RM3000 per month No terminal illness, dementia and mental illness | -NA- | Among elderly population

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 39. | Rohida, S.H., Suzana, S., Norhayati, I. and Hanis Mastura, Y. [112] (2017) | Cross-sectional study | n = 289 Older adults aged 60 years and over from FELDA Land Development Authority (FELDA)—Northern Region of Malaysia | -NA- | Among elderly population

| -NA- | -NA- |

| 40. | Siti Farhana, M., Norhasmah, S., Zalilah, M.S., Zuriati, I. [114] (2020) | Cross-sectional study | n = 220 Elderly people aged 60 years and over | -NA- | Among elderly population

| -NA- | -NA- |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulaiman, N.; Yeatman, H.; Russell, J.; Law, L.S. A Food Insecurity Systematic Review: Experience from Malaysia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030945

Sulaiman N, Yeatman H, Russell J, Law LS. A Food Insecurity Systematic Review: Experience from Malaysia. Nutrients. 2021; 13(3):945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030945

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulaiman, Norhasmah, Heather Yeatman, Joanna Russell, and Leh Shii Law. 2021. "A Food Insecurity Systematic Review: Experience from Malaysia" Nutrients 13, no. 3: 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030945

APA StyleSulaiman, N., Yeatman, H., Russell, J., & Law, L. S. (2021). A Food Insecurity Systematic Review: Experience from Malaysia. Nutrients, 13(3), 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030945