Betel Nut Chewing Decreased Calcaneus Ultrasound T-Score in a Large Taiwanese Population Follow-Up Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

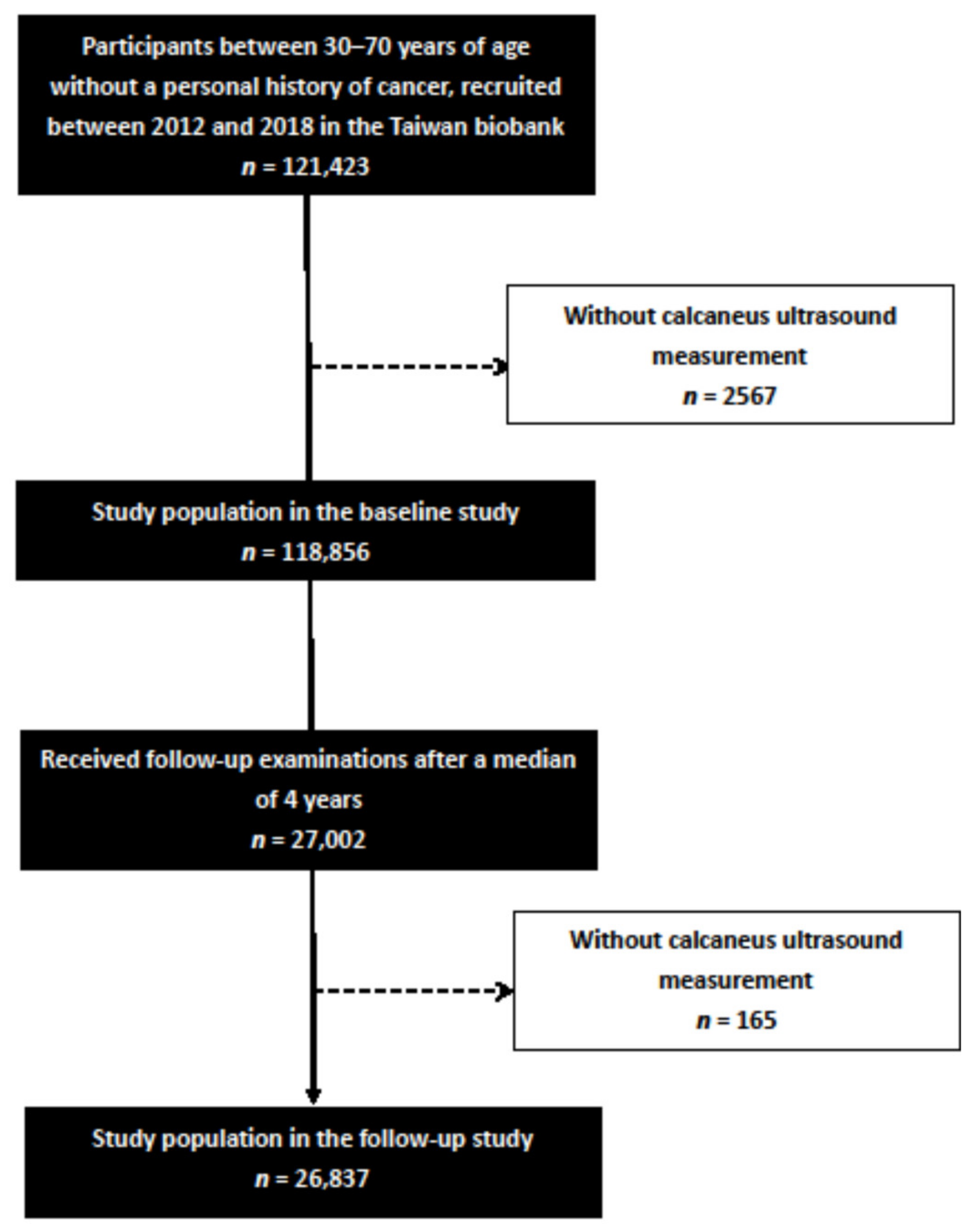

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. TWB

2.3. Collection of Study Variables

2.3.1. Assessment of Betel Nut Chewing

2.3.2. Assessment of Calcaneus Ultrasound T-Score

2.3.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics among the Participants According to BASELINE Calcaneus Ultrasound T Score ≥ −2.5 or <−2.5

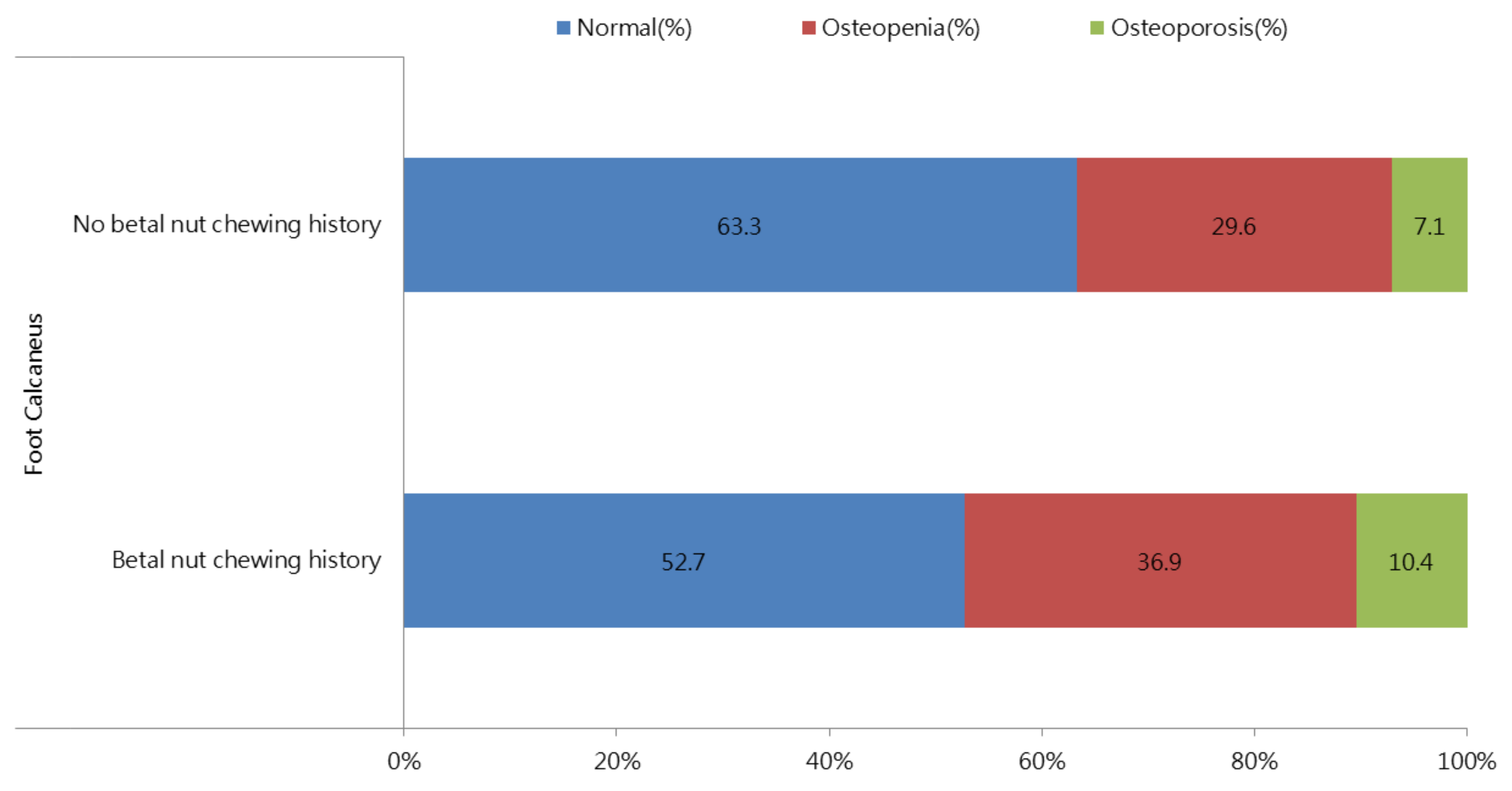

3.2. Correlation between a History of Betel Nut Chewing and Baseline T-Score in All Participants

3.3. Correlation between Duration of Chewing Betel Nut and Baseline T-Score in the Participants with a History of Betel Nut Chewing

3.4. Correlation between Duration of Chewing Betel Nut and ΔT-Score in the Participants with a History of Chewing Betel Nut

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Riggs, B.L.; Melton, L.J., 3rd. The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: Insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone 1995, 17 (Suppl. S5), 505s–511s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.; Dennison, E.; Cooper, C. Osteoporosis: Impact on health and economics. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2010, 6, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holroyd, C.; Cooper, C.; Dennison, E. Epidemiology of osteoporosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 22, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, A.L.; Laya, M.B. Osteoporosis: Screening, prevention, and management. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 99, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisani, P.; Renna, M.D.; Conversano, F.; Casciaro, E.; Di Paola, M.; Quarta, E.; Muratore, M.; Casciaro, S. Major osteoporotic fragility fractures: Risk factor updates and societal impact. World J. Orthop. 2016, 7, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, J.; Sem, G.; Sit, E.; Tai, M.C.-T. The ethics of betel nut consumption in Taiwan. J. Med. Ethics 2017, 43, 739–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2020 Health Promotion Administration Annual Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/EngPages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=1070&pid=13282 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Garg, A.; Chaturvedi, P.; Gupta, P.C. A review of the systemic adverse effects of areca nut or betel nut. Indian J. Med. Paediatr. Oncol. 2014, 35, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Peng, W.; Hu, M.-B.; Xu, M.; Wu, C.-J. The pharmacology, toxicology and potential applications of arecoline: A review. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 2753–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.; Idle, J.R.; Chen, C.; Zabriskie, T.M.; Krausz, K.W.; Gonzalez, F.J. A metabolomic approach to the metabolism of the areca nut alkaloids arecoline and arecaidine in the mouse. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wenke, G.; Rivenson, A.; Brunnemann, K.D.; Hoffmann, D.; Bhide, S.V. A study of betel quid carcinogenesis. II. Formation of N-nitrosamines during betel quid chewing. IARC Sci. Publ. 1984, 57, 859–866. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Betel-Quid and Areca-Nut Chewing and Some Areca-Nut Derived Nitrosamines; IARC: Lyon, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, U.J.; Floyd, R.A.; Nair, J.; Bussachini, V.; Friesen, M.; Bartsch, H. Formation of reactive oxygen species and of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine in DNA in vitro with betel quid ingredients. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 1987, 63, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-N.; Ting, C.-C.; Shieh, T.-Y.; Ko, E.C. Relationship between betel quid chewing and radiographic alveolar bone loss among Taiwanese aboriginals: A retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, S.; Chen, R.; Luo, K.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, M.; Du, G. Areca nut extract protects against ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis in mice. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 13, 2893–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, F.-L.; Chen, C.-L.; Lai, C.-C.; Lee, C.-C.; Chang, D.-M. Arecoline suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation in vitro and attenuates LPS-induced bone loss in vivo. Phytomedicine 2020, 69, 153195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Yang, J.-H.; Chiang, C.; Hsiung, C.-N.; Wu, P.-E.; Chang, L.-C.; Chu, H.-W.; Chang, J.; Yuan-Tsong, C.; Yang, S.-L.; et al. Population structure of Han Chinese in the modern Taiwanese population based on 10,000 participants in the Taiwan Biobank project. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 5321–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, C.-T.; Hung, T.-H.; Yeh, C.-K. Taiwan Regulation of Biobanks. J. Law Med. Ethic 2015, 43, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Bosch, J.P.; Lewis, J.B.; Greene, T.; Rogers, N.; Roth, D.R.; The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, L.-J.; Ho, F.-C.; Chen, Y.-T.; Holborow, D.W.; Liu, T.-Y.; Hung, S.-L. Areca nut extracts modulated expression of alkaline phosphatase and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand in osteoblasts. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2005, 32, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Shima, N.; Nakagawa, N.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kinosaki, M.; Mochizuki, S.-I.; Tomoyasu, A.; Yano, K.; Goto, M.; Murakami, A.; et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 3597–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, G.S.; Lian, J.B.; Owen, T.A. Relationship of cell growth to the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression during osteoblast differentiation. FASEB J. 1990, 4, 3111–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hofbauer, L.C.; Lacey, D.; Dunstan, C.; Spelsberg, T.; Riggs, B.; Khosla, S. Interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, but not interleukin-6, stimulate osteoprotegerin ligand gene expression in human osteoblastic cells. Bone 1999, 25, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M.C.; Choi, Y. Biology of the RANKL-RANK-OPG System in Immunity, Bone, and Beyond. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cox, S.; Vickers, E.R.; Ghu, S.; Zoellner, H. Salivary arecoline levels during areca nut chewing in human volunteers. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2010, 39, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.; Ohshima, H.; Friesen, M.; Croisy, A.; Bhide, S.; Bartsch, H. Tobacco-specific and betel nut-specific N-nitroso compounds: Occurrence in saliva and urine of betel quid chewers and formation in vitro by nitrosation of betel quid. Carcinogenesis 1985, 6, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.C.; Ray, C.S. Epidemiology of betel quid usage. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2004, 33, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lauderdale, D.S.; Salant, T.; Han, K.L.; Tran, P.L. Life-course predictors of ultrasonic heel measurement in a cross-sectional study of immigrant women from Southeast Asia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 153, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Clowes, J.A.; Riggs, B.L.; Khosla, S. The role of the immune system in the pathophysiology of osteoporosis. Immunol. Rev. 2005, 208, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuzawa, T.; Miyaura, C.; Onoe, Y.; Kusano, K.; Ohta, H.; Nozawa, S.; Suda, T. Estrogen deficiency stimulates B lymphopoiesis in mouse bone marrow. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbali-Fatourechi, G.; Khosla, S.; Sanyal, A.; Boyle, W.J.; Lacey, D.L.; Riggs, B.L. Role of RANK ligand in mediating increased bone resorption in early postmenopausal women. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 111, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amelio, P.; Grimaldi, A.; Di, B.S.; Brianza, S.Z.; Cristofaro, M.A.; Tamone, C.; Giribaldi, G.; Ulliers, D.; Pescarmona, G.P.; Isaia, G. Estrogen deficiency increases osteoclasto-genesis up-regulating T cells activity: A key mechanism in osteoporosis. Bone 2008, 43, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Takahashi, N.; Jimi, E.; Udagawa, N.; Takami, M.; Kotake, S.; Nakagawa, N.; Kinosaki, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shima, N.; et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor α Stimulates Osteoclast Differentiation by a Mechanism Independent of the Odf/Rankl–Rank Interaction. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeilschifter, J.; Chenu, C.; Bird, A.; Mundy, G.R.; Roodman, D.G. Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor stimulate the formation of human osteoclastlike cells in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1989, 4, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontova, R.; Gutiérrez, C.; Vendrell, J.; Broch, M.; Simón, I.; Fernández-Real, J.M.; Richart, C. Bone mineral mass is associated with interleukin 1 receptor autoantigen and TNF-α gene polymorphisms in post-menopausal Mediterranean women. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2002, 25, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscitti, P.; Cipriani, P.; Carubbi, F.; Liakouli, V.; Zazzeroni, F.; Di Benedetto, P.; Berardicurti, O.; Alesse, E.; Giacomelli, R. The Role of IL-1β in the Bone Loss during Rheumatic Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 12, 782382. [Google Scholar]

- Valderrábano, R.J.; Lui, L.-Y.; Lee, J.; Cummings, S.R.; Orwoll, E.S.; Hoffman, A.R.; Wu, J.Y. Osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study research group bone density loss is associated with blood cell counts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 32, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chakravarti, A.; Raquil, M.A.; Tessier, P.; Poubelle, P.E. Surface RANKL of Toll-like receptor 4-stimulated human neutrophils activates osteoclastic bone resorption. Blood 2009, 8, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faouzi, M.; Neupane, R.; Yang, J.; Williams, P.; Penner, R. Areca nut extracts mobilize calcium and release pro-inflammatory cyto-kines from various immune cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bickel, M. The role of interleukin-8 in inflammation and mechanisms of regulation. J. Periodontol. 1993, 64, 456–460. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Sugimoto, T.; Yano, S.; Yamauchi, M.; Sowa, H.; Chen, Q.; Chihara, K. Plasma Lipids and Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women. Endocr. J. 2002, 49, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bijelic, R.; Balaban, J.; Milicevic, S. Correlation of the Lipid Profile, BMI and Bone Mineral Density in Postmenopausal Women. Mater. Socio Med. 2016, 28, 412–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holmberg, A.H.; Nilsson, P.M.; Nilsson, J.A.; Akesson, K. The Association between Hyperglycemia and Fracture Risk in Middle Age. A Prospective, Population-Based Study of 22,444 Men and 10,902 Women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.-Y.; Suhaimi, F.H.; Ahmad, F.; Ima-Nirwana, S. The relationship between metabolic syndrome and Osteoporosis: A Review. Nutrients 2016, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tanaka, K.I.; Yamaguchi, T.; Kanazawa, I.; Sugimoto, T. Effects of high glucose and advanced glycation end products on the ex-pressions of sclerostin and RANKL as well as apoptosis in osteocyte-like MLO-Y4-A2 cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 461, 193–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Sheu, M.-L.; Tsai, K.S.; Yang, R.S.; Liu, S.H. Advanced Glycation End Products Induce Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Down-Regulation-Related Inflammatory Signals in Human Chondrocytes via Toll-Like Receptor-4 and Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akune, T.; Ohba, S.; Kamekura, S.; Yamaguchi, M.; Chung, U.I.; Kubota, N.; Terauchi, Y.; Harada, Y.; Azuma, Y.; Nakamura, K.; et al. PPARgamma insufficiency enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 846–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tintut, Y.; Morony, S.; Demer, L.L. Hyperlipidemia promotes osteoclastic potential of bone marrow cells ex vivo. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, e6–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brites, F.; Martin, M.; Guillas, I.; Kontush, A. Antioxidative activity of high-density lipoprotein (HDL): Mechanistic insights into potential clinical benefit. BBA Clin. 2017, 8, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paik, J.M.; Kim, S.C.; Feskanich, D.; Choi, H.K.; Solomon, D.H.; Curhan, G.C. Gout and risk of fracture in women: A Prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 69, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehta, T.; Bůžková, P.; Sarnak, M.J.; Chonchol, M.; Cauley, J.A.; Wallace, E.; Fink, H.A.; Robbins, J.; Jalal, D. Serum urate levels and the risk of hip fractures: Data from the cardiovascular health study. Metabolism 2015, 64, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Makovey, J.; Macara, M.; Chen, J.S.; Hayward, C.S.; March, L.; Seibel, M.; Sambrook, P.N. Serum uric acid plays a protective role for bone loss in peri- and postmenopausal women: A longitudinal study. Bone 2013, 52, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sautin, Y.Y.; Johnson, R.J. Uric Acid: The Oxidant-Antioxidant Paradox. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2008, 27, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Santos, C.X.; Anjos, E.I.; Augusto, O. Uric acid oxidation by peroxynitrite: Multiple reactions, free radical formation, and amplification of lipid oxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 372, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokose, K.; Sato, S.; Asano, T.; Yashiro, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Watanabe, H.; Suzuki, E.; Sato, C.; Kozuru, H.; Yatsuhashi, H.; et al. TNF-α potentiates uric acid-induced interleukin-1β (IL-1β) secretion in human neutrophils. Mod. Rheumatol. 2018, 28, 513–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Giovine, F.S.; Malawista, S.E.; Thornton, E.; Duff, G.W. Urate crystals stimulate production of tumor necrosis factor alpha from human blood monocytes and synovial cells. Cytokine mRNA and protein kinetics, and cellular distribution. J. Clin. Investig. 1991, 87, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jin, N.; Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F. Assess the discrimination of Achilles InSight calcaneus quantitative ultrasound device for os-teoporosis in Chinese women: Compared with dual energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements. Eur. J. Radiol. 2010, 76, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | T-Score ≥ −2.5 (n = 110,227) | T-Score < −2.5 (n = 8629) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 49.3 ± 10.9 | 57.2 ± 9.1 | <0.001 |

| Male gender (%) | 35.5 | 41.2 | <0.001 |

| Smoking history (%) | 27.0 | 30.1 | <0.001 |

| DM (%) | 5.0 | 6.9 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 11.9 | 17.0 | <0.001 |

| Betel nut chewing history (%) | 5.9 | 8.7 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.3 ± 3.8 | 23.6 ± 3.7 | <0.001 |

| Baseline T-score | −0.18 ± 1.49 | −3.1 ± 0.49 | <0.001 |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| White blood cell (×103/uL) | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.7 ± 1.6 | 13.8 ± 1.5 | 0.005 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 95.7 ± 20.4 | 98.3 ± 23.4 | <0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 115.2 ± 94.6 | 119.6 ± 86.7 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 195.4 ± 35.7 | 199.0 ± 37.0 | <0.001 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 54.5 ± 13.4 | 55.1 ± 14.2 | 0.001 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 120.9 ± 31.7 | 122.3 ± 32.5 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 33.3 ± 46.3 | 38.8 ± 48.7 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 0.114 |

| Variables | Multivariable (Baseline T-Score) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficient β (95% CI) | p | |

| Betel nut chewing history | −0.232 (−0.271, −0.193) | <0.001 |

| Age (per 1 year) | −0.056 (−0.057, −0.055) | <0.001 |

| Male (vs. female) | 0.473 (0.397, 0.550) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | −0.001 (−0.024, 0.022) | 0.955 |

| DM | 0.096 (0.052, 0.140) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | −0.070 (−0.098, −0.042) | <0.001 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.055 (0.052, 0.057) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| White blood cell (per 1 × 103/uL) | −0.093 (−0.018, −0.007) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (per 1 g/dL) | 0.018 (0.011, 0.025) | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (per 1 mg/dL) | −0.001 (−0.001, 0) | 0.037 |

| Triglyceride (per 1 mg/dL) | −0.001 (−0.001, 0) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | 1.022×10−5 (−0.001, 0.001) | 0.984 |

| HDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | 0.002 (0.001, 0.004) | <0.001 |

| LDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | −0.001 (−0.002, 0) | 0.021 |

| eGFR (per 1 mL/min/1.73 m2) | −0.010 (−0.011, −0.009) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (per 1 mg/dL) | −0.014 (−0.022, −0.006) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Multivariable (T-Score) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficient β (95% CI) | p | |

| Betel nut chewing years (per 1 year) | −0.003 (−0.006, −0.001) | 0.022 |

| Age (per 1 year) | −0.026 (−0.030, −0.023) | <0.001 |

| Male (vs. female) | −0.335 (−0.589, −0.081) | 0.010 |

| Smoking history | −0.179 (−0.315, −0.042) | 0.010 |

| DM | 0.080 (−0.048, 0.208) | 0.219 |

| Hypertension | −0.061 (−0.144, 0.023) | 0.157 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.036 (0.027, 0.045) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| White blood cell (per 1 × 103/uL) | −0.036 (−0.054, −0.019) | 0.022 |

| Hemoglobin (per 1 g/dL) | 0.061 (0.035, 0.087) | <0.001 |

| Fasting glucose (per 1 mg/dL) | 0 (−0.001, 0.002) | 0.622 |

| Triglyceride (per 1 mg/dL) | 0 (−0.001, 0) | 0.125 |

| Total cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | 0.001 (−0.002, 0.004) | 0.567 |

| HDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | 0.001 (−0.004, 0.005) | 0.795 |

| LDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | −0.001 (−0.004, 0.002) | 0.403 |

| eGFR (per 1 mL/min/1.73 m2) | −0.004 (−0.005, −0.002) | <0.001 |

| Uric acid (per 1 mg/dL) | −0.015 (−0.038, 0.009) | 0.224 |

| Variables | Multivariable (ΔT-Score) | |

|---|---|---|

| Unstandardized Coefficient β (95% CI) | p | |

| Betel nut chewing years (per 1 year) | −0.004 (−0.008, 0) | 0.039 |

| Age (per 1 year) | 0.001 (−0.004, 0.006) | 0.754 |

| Male (vs. female) | 0.051 (−0.254, 0.355) | 0.745 |

| Smoking history | 0.032 (−0.169, 0.233) | 0.757 |

| DM | −0.092 (−0.278, 0.095) | 0.334 |

| Hypertension | 0.075 (−0.044, 0.194) | 0.218 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | −0.006 (−0.020, 0.008) | 0.428 |

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| White blood cell (per 1 × 103/uL) | −0.005 (−0.032, 0.021) | 0.688 |

| Hemoglobin (per 1 g/dL) | −0.009 (−0.047, 0.029) | 0.638 |

| Fasting glucose (per 1 mg/dL) | 0 (−0.002, 0.002) | 0.832 |

| Triglyceride (per 1 mg/dL) | −5.358×10−5 (−0.001, 0.001) | 0.890 |

| Total cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | −0.001 (−0.005, 0.004) | 0.829 |

| HDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | 0.003 (−0.004, 0.009) | 0.430 |

| LDL-cholesterol (per 1 mg/dL) | 6.104×10−5 (−0.005, 0.005) | 0.980 |

| eGFR (per 1 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0 (−0.003, 0.002) | 0.715 |

| Uric acid (per 1 mg/dL) | 0.029 (−0.006, 0.063) | 0.105 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, Y.-H.; Geng, J.-H.; Wu, D.-W.; Chen, S.-C.; Hung, C.-H.; Kuo, C.-H. Betel Nut Chewing Decreased Calcaneus Ultrasound T-Score in a Large Taiwanese Population Follow-Up Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103655

Lu Y-H, Geng J-H, Wu D-W, Chen S-C, Hung C-H, Kuo C-H. Betel Nut Chewing Decreased Calcaneus Ultrasound T-Score in a Large Taiwanese Population Follow-Up Study. Nutrients. 2021; 13(10):3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103655

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Ying-Hsuan, Jiun-Hung Geng, Da-Wei Wu, Szu-Chia Chen, Chih-Hsing Hung, and Chao-Hung Kuo. 2021. "Betel Nut Chewing Decreased Calcaneus Ultrasound T-Score in a Large Taiwanese Population Follow-Up Study" Nutrients 13, no. 10: 3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103655

APA StyleLu, Y.-H., Geng, J.-H., Wu, D.-W., Chen, S.-C., Hung, C.-H., & Kuo, C.-H. (2021). Betel Nut Chewing Decreased Calcaneus Ultrasound T-Score in a Large Taiwanese Population Follow-Up Study. Nutrients, 13(10), 3655. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103655