Efficacy of Oral Vitamin Supplementation in Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

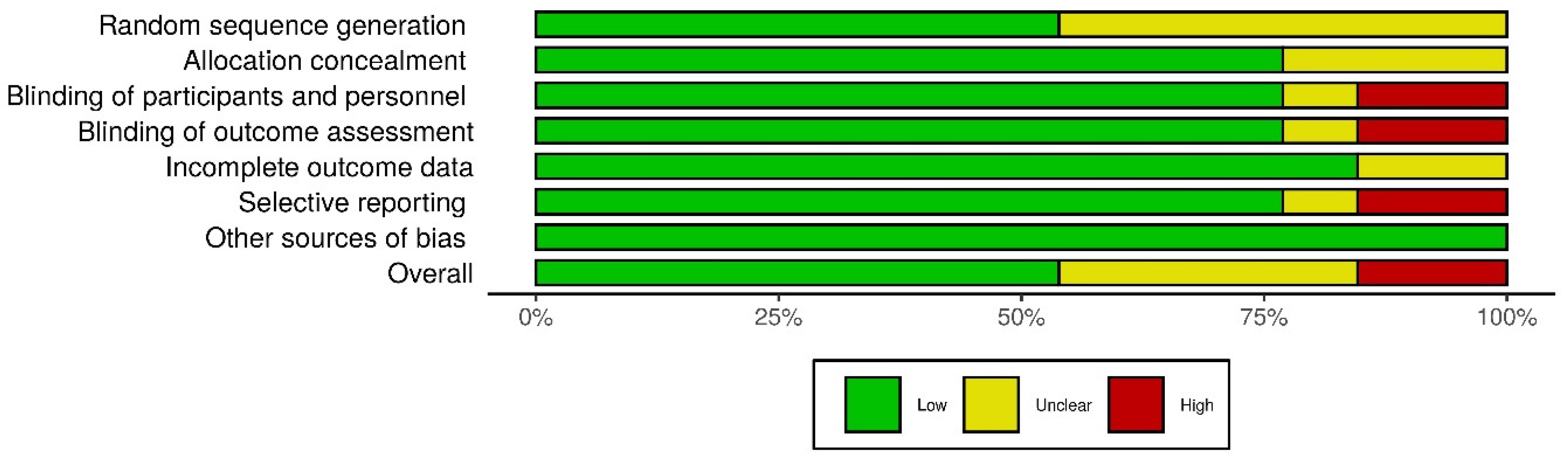

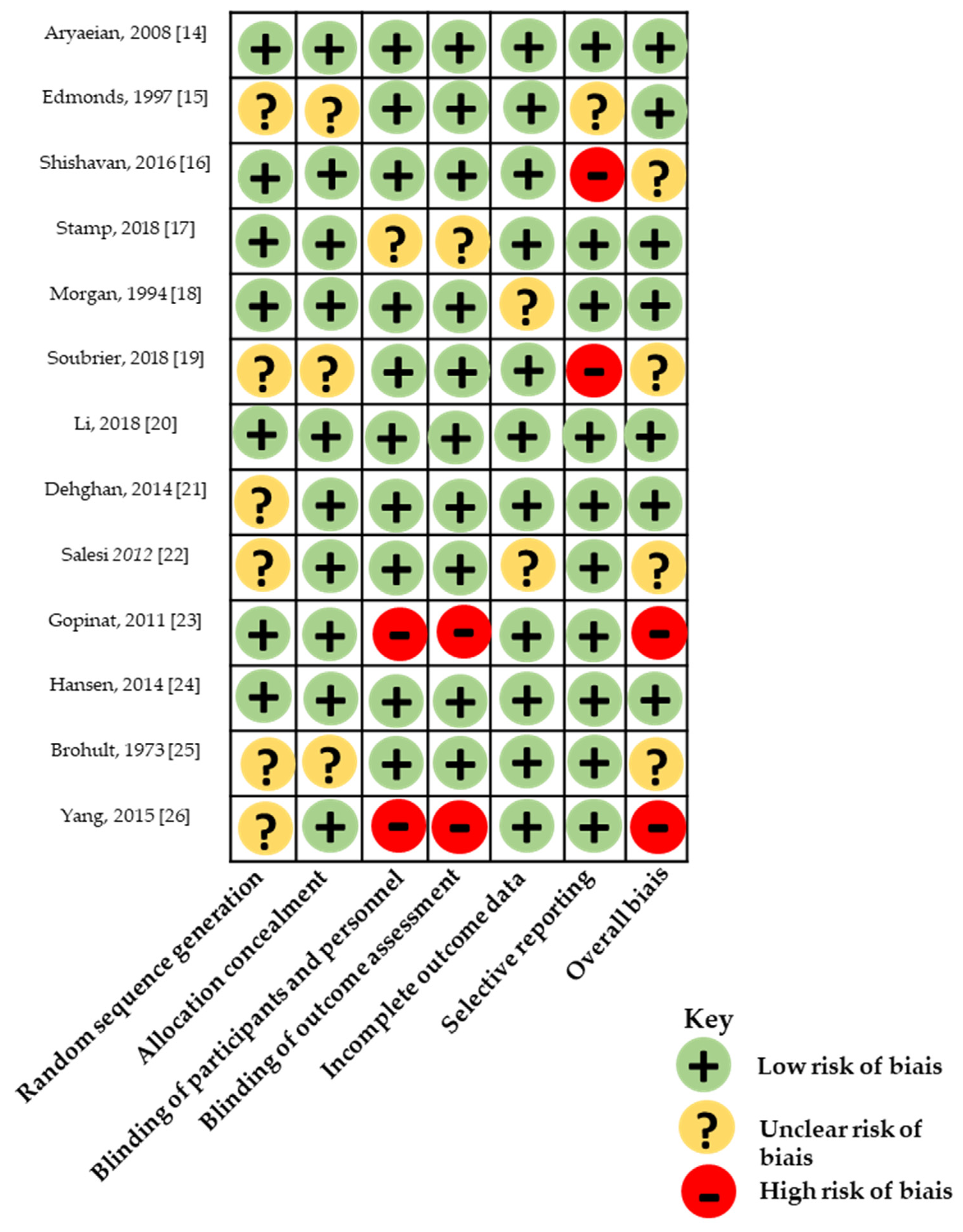

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

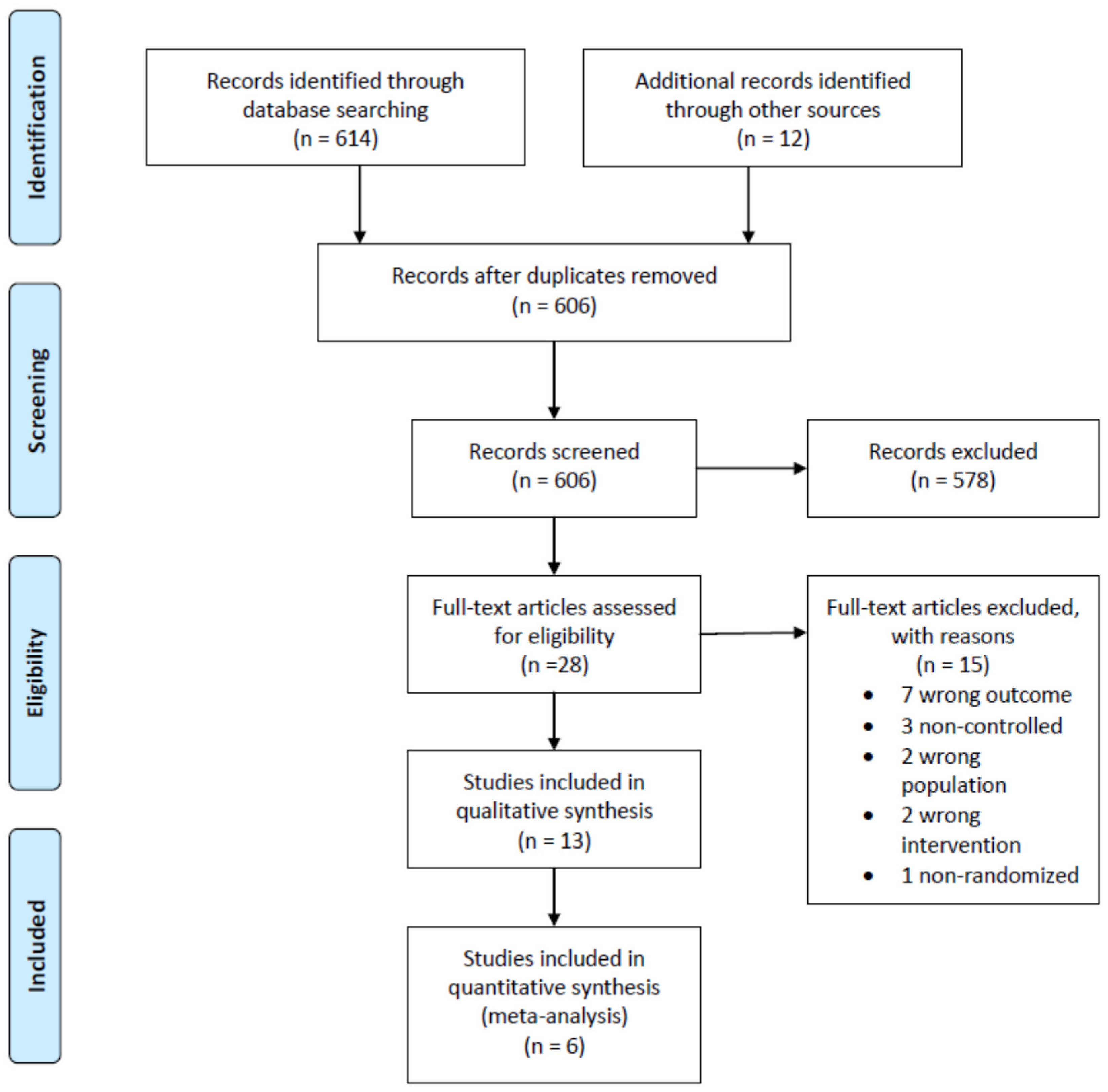

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias within Studies

3.4. Outcomes

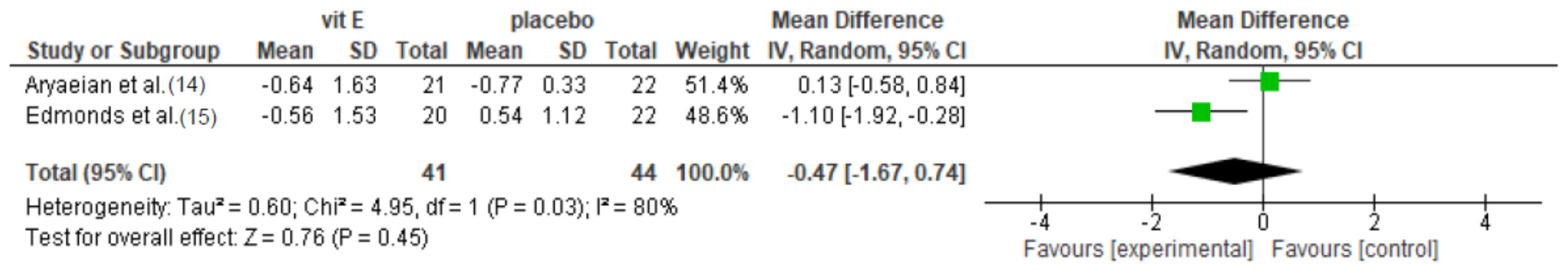

3.4.1. Vitamin E Supplementation

3.4.2. Vitamin K Supplementation

3.4.3. Folic Acid Supplementation

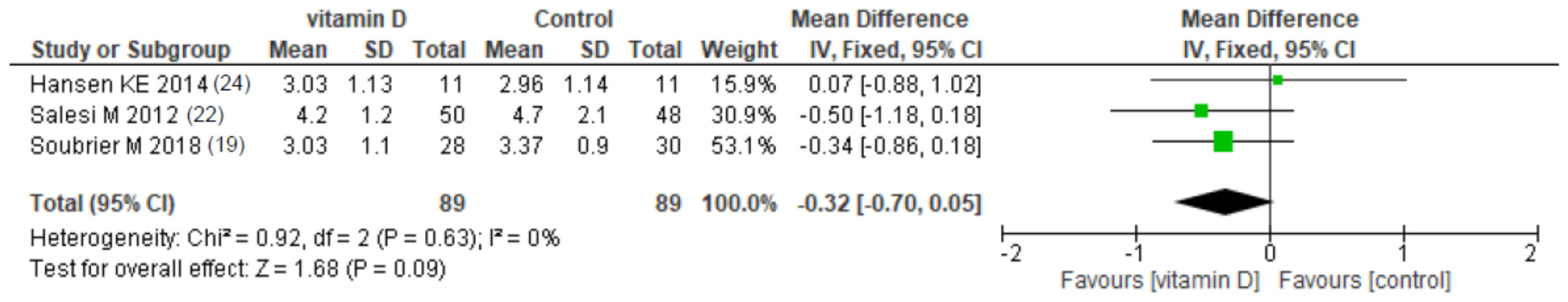

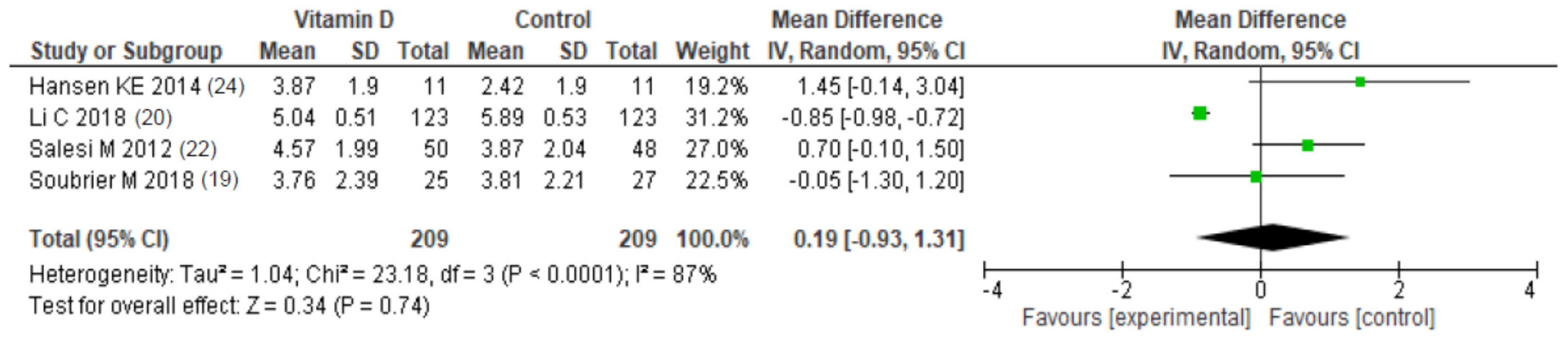

3.4.4. Vitamin D Supplementation

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy

Appendix B

| Study | Randomization | Blinding | Account of All Patients | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aryaeian et al. [14] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Edmonds et al. [15] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Shishavan et al. [16] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Stamp et al. [17] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Morgan et al. [18] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Soubrier et al. [19] | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Li et al. [20] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Dehghan et al. [21] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Salesi et al. [22] | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Gopinath et al. [23] | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Hansen et al. [24] | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Brohult et al. [25] | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Yang et al. [26] | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

References

- Provvedini, D.M.; Tsoukas, C.D.; Deftos, L.J.; Manolagas, S.C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Receptors in Human Leukocytes. Science 1983, 221, 1181–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, C.; Sartory, N.A.; Zahn, N.; Radeke, H.H.; Stein, J.M. Immune Modulatory Treatment of Trinitrobenzene Sulfonic Acid Colitis with Calcitriol Is Associated with a Change of a T Helper (Th) 1/Th17 to a Th2 and Regulatory T Cell Profile. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 324, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, A.; Barrat, F.J.; Crain, C.; Heath, V.L.; Savelkoul, H.F.; O’Garra, A. 1alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Has a Direct Effect on Naive CD4(+) T Cells to Enhance the Development of Th2 Cells. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 2001, 167, 4974–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, X.; Semerano, L.; Decker, P.; Falgarone, G.; Boissier, M.-C. Pain and Immunity. Jt. Bone Spine 2012, 79, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantorna, M.T.; Hayes, C.E.; DeLuca, H.F. 1,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol Inhibits the Progression of Arthritis in Murine Models of Human Arthritis. J. Nutr. 1998, 128, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchon, C.A.; El-Gabalawy, H.S. Oxidation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2004, 6, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Okamoto, H. Vitamin K and Rheumatoid Arthritis. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S.; Rasouli-Ghahroudi, A.A. Vitamin K and Bone Metabolism: A Review of the Latest Evidence in Preclinical Studies. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4629383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Burmester, G.R.; Dougados, M.; Kerschbaumer, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Sepriano, A.; Vollenhoven, R.F.V.; Wit, M.D.; et al. EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Synthetic and Biological Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: 2019 Update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: /handbook/current (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-Bias VISualization (Robvis): An R Package and Shiny Web App for Visualizing Risk-of-Bias Assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appendix: Jadad Scale for Reporting Randomized Controlled Trials. In Evidence-Based Obstetric Anesthesia; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-0-470-98834-3.

- Aryaeian, N.; Shahram, F.; Djalali, M.; Eshragian, M.R.; Djazayeri, A.; Sarrafnejad, A.; Salimzadeh, A.; Naderi, N.; Maryam, C. Effect of Conjugated Linoleic Acids, Vitamin E and Their Combination on the Clinical Outcome of Iranian Adults with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 12, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, S.E.; Winyard, P.G.; Guo, R.; Kidd, B.; Merry, P.; Langrish-Smith, A.; Hansen, C.; Ramm, S.; Blake, D.R. Putative Analgesic Activity of Repeated Oral Doses of Vitamin E in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Results of a Prospective Placebo Controlled Double Blind Trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1997, 56, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shishavan, N.G.; Gargari, B.P.; Kolahi, S.; Hajialilo, M.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Javadzadeh, Y. Effects of Vitamin K on Matrix Metalloproteinase-3 and Rheumatoid Factor in Women with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamp, L.K.; OʼDonnell, J.L.; Frampton, C.; Drake, J.; Zhang, M.; Barclay, M.; Chapman, P.T. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Double-Blind Trial of High- Versus Low-Dose Weekly Folic Acid in People With Rheumatoid Arthritis Receiving Methotrexate: JCR. J Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 25, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, S.L.; Baggott, J.E.; Vaughn, W.H.; Austin, J.S.; Veitch, T.A.; Lee, J.Y.; Koopman, W.J.; Krumdieck, C.L.; Alarcon, G.S. Supplementation with Folic Acid during Methotrexate Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubrier, M.; Lambert, C.; Combe, B.; Gaudin, P.; Thomas, T.; Sibilia, J.; Dougados, M.; Dubost, J.-J. A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study Assessing the Efficacy of High Doses of Vitamin D on Functional Disability in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2018, 36, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Yin, S.; Yin, H.; Cao, L.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y. Efficacy and Safety of 22-Oxa-Calcitriol in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Phase II Trial. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2018, 24, 9127–9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, A.; Rahimpour, S.; Soleymani-Salehabadi, H.; Owlia, M.B. Role of Vitamin D in Flare Ups of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Z. Rheumatol. 2014, 73, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesi, M.; Farajzadegan, Z. Efficacy of Vitamin D in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis Receiving Methotrexate Therapy. Rheumatol. Int. 2012, 32, 2129–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, K.; Danda, D. Supplementation of 1,25 Dihydroxy Vitamin D3 in Patients with Treatment Naive Early Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Randomised Controlled Trial: Vitamin D in RA. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 14, 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, K.E.; Bartels, C.M.; Gangnon, R.E.; Jones, A.N.; Gogineni, J. An Evaluation of High-Dose Vitamin D for Rheumatoid Arthritis: JCR. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 20, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brohult, J.; Jonson, B. Effects of Large Doses of Calciferol on Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1973, 2, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, M.; Wang, J. Effect of Vitamin D on the Recurrence Rate of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.S.; Freitas, T.Q.; Bernardo, W.M.; Pereira, R.M.R. Vitamin D Supplementation and Disease Activity in Patients with Immune-Mediated Rheumatic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine 2017, 96, e7024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daien, C.; Hua, C.; Gaujoux-Viala, C.; Cantagrel, A.; Dubremetz, M.; Dougados, M.; Fautrel, B.; Mariette, X.; Nayral, N.; Richez, C.; et al. Update of French Society for Rheumatology Recommendations for Managing Rheumatoid Arthritis. Jt. Bone Spine 2019, 86, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avouac, J.; Koumakis, E.; Toth, E.; Meunier, M.; Maury, E.; Kahan, A.; Cormier, C.; Allanore, Y. Increased Risk of Osteoporosis and Fracture in Women with Systemic Sclerosis: A Comparative Study with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 64, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Watad, A.; Neumann, S.G.; Simon, M.; Brown, S.B.; Abu Much, A.; Harari, A.; Tiosano, S.; Amital, H.; Shoenfeld, Y. Vitamin D and Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Ongoing Mystery. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017, 29, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billington, E.O.; Burt, L.A.; Rose, M.S.; Davison, E.M.; Gaudet, S.; Kan, M.; Boyd, S.K.; Hanley, D.A. Safety of High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 1261–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, L.; Guyatt, G.; Fink, H.A.; Cannon, M.; Grossman, J.; Hansen, K.E.; Humphrey, M.B.; Lane, N.E.; Magrey, M.; Miller, M.; et al. 2017 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Prevention and Treatment of Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. Hoboken NJ 2017, 69, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoes, J.N.; Jacobs, J.W.G.; Boers, M.; Boumpas, D.; Buttgereit, F.; Caeyers, N.; Choy, E.H.; Cutolo, M.; Da Silva, J.A.P.; Esselens, G.; et al. EULAR Evidence-Based Recommendations on the Management of Systemic Glucocorticoid Therapy in Rheumatic Diseases. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intervention Group | Control Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Age (Years) | Disease Duration (Years) | Age (Years) | Disease Duration (Years) | ||

| Aryaeian, 2008 [14] | Iran | ACR 1987, at least 2 years evolution | 49.33 | 7.24 | 47.95 | 7.9 |

| Edmonds, 1997 [15] | UK | ACR 1987, RAI ≥ 6 or MS ≥ 1 h | 55.4 | NR | 52 | NR |

| Shishavan, 2016 [16] | Iran | ACR 1987, 20–50 years old, DAS-28 < 5.1 | 38 | 3 | 39 | 7 |

| Stamp, 2018 [17] | New Zealand | ACR 1987, under methotrexate and folic acid ≥ 3 months, DAS-28 ≥ 3.2 | 61.9 | 9.8 | 57.2 | 9.5 |

| Morgan, 1994 [18] | UK | ARA 1987, 19–78 years, >6 months, active (TJC ≥ 6, SJC ≥ 3, MS ≥ 45 min, ESR ≥ 28 mm) | 5 mg: 54 27.5 mg: 53.2 | 5 mg: 7.4 27.5 mg: 11.6 | 52.2 | 8.5 |

| Soubrier, 2018 [19] | France | ACR 1987, DAS28 ≥ 2.6, vitamin D < 30 ng/mL | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Li, 2018 [20] | China | ACR/EULAR criteria, TJC ≥ 4 | 22-Oxa: 48.5 Calcitriol: 49.6 | 22-Oxa: 6.5 Calcitriol: 6.6 | 51.1 | 6.9 |

| Dehghan, 2014 [21] | Iran | ACR/EULAR criteria, in remission for > 2 years, vitamin D < 30 ng/mL | 45 | NR | 4.7 | NR |

| Salesi 2012 [22] | Iran | ACR 1987, DAS-28 ≥ 3.2 | 49.9 | NR | 50 | NR |

| Gopinat, 2011 [23] | India | Early RA < 2 years without treatments | 44.9 | 0.64 | 44.9 | 0.57 |

| Hansen, 2014 [24] | USA | ACR 1987, vitamin D < 25 ng/mL | 63 | NR | 63 | NR |

| Brohult, 1973 [25] | Sweden | ACR 1987, >2 years evolution | 53 | NR | 51 | NR |

| Yang, 2015 [26] | China | ACR/EULAR criteria, in remission for >2 years | 44.2 | 4.9 | 41.7 | 5.1 |

| Study | Design | Population | Intervention | Controls | Outcome | Outcome Measurement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | N | Type | N | |||||

| Vitamin E | ||||||||

| Aryaeian, 2008 [14] | Double blind RCT | 102 randomized in 4 groups * incl. 51 in vitamin E or placebo groups → 43 completed | Vitamin E 400 mg/day for 12 weeks | 21 | Placebo for 12 weeks | 22 | DAS-28, VAS pain, SJC, TJC, Morning stiffness | 12 weeks |

| Edmonds, 1997 [15] | Double blind RCT | 42 randomized → 39 completed | Vitamin E 600 mg twice daily for 12 weeks | 20 | Placebo for 12 weeks | 19 | Ritchie articular index, morning stiffness, SJC, VAS pain | 12 weeks |

| Vitamin K | ||||||||

| Shishavan, 2016 [16] | Double blind RCT | 64 randomized → 58 completed | Vitamin K 10 mg/day for 8 weeks | 30 | Placebo for 8 weeks | 28 | DAS-28 | 8 weeks |

| Folic acid | ||||||||

| Stamp, 2018 [17] | Double blind RCT | 40 randomized and completed | Folic acid 5 mg/day for 24 weeks | 22 | Folic acid 0.8 mg/day for 24 weeks | 18 | DAS-28 | 24 weeks |

| Morgan, 1994 [18] | Double blind RCT | 94 randomized → 79 completed the study in three groups | Folic acid 5 mg/day or 27.5 mg/day for 1 year | 25 + 26 | Placebo | 28 | Ritchie articular index, Joint indices for tenderness and swelling, HAQ | 1 year |

| Vitamin D | ||||||||

| Soubrier, 2018 [19] | Double blind RCT | 59 randomized → 59 completed | Cholecalciferol 100,000 IU (frequency depending on the baseline vitamin D dosage) for 24 weeks | 30 | Placebo | 29 | HAQ, DAS-28, VAS pain | 24 weeks |

| Li, 2018 [20] | Double blind RCT | 369 randomized → 369 completed | 22-Oxa-Calcitriol 50,000 IU/week for 6 weeks or Calcitriol 50,000 IU/week for 6 weeks | 123 + 123 | Placebo | 123 | SJC, VAS pain, HAQ | 6 weeks |

| Dehghan, 2014 [21] | Double blind RCT | 80 randomized → 80 completed | Cholecalciferol 50,000 IU/week for 6 months | 40 | Placebo | 40 | Number of flares | 6 months |

| Salesi 2012 [22] | Double blind RCT | 117 eligible → 98 | Cholecalciferol 50,000 IU/week for 12 weeks | 50 | Placebo | 48 | DAS-28, TJC, SJC, VAS pain | 12 weeks |

| Gopinat, 2011 [23] | Open label RCT | 204 identified → 121 randomized → 110 completed | Calcitriol 500 IU + Calcium 1000 mg per day for 12 weeks | 59 | Calcium 1000 mg per day | 62 | Time to achieve pain relief, number of patients with VAS pain reduction | 12 weeks |

| Hansen, 2014 [24] | Double blind RCT | 711 contacted → 98 eligible → 22 randomized | Ergocalciferol 50,000 IU 3 times/week for one month then twice a month for 8 weeks | 11 | Placebo | 11 | HAQ, DAS-28, VAS pain | 1 year |

| Brohult, 1973 [25] | Double blind RCT | 49 | Calciferol 100,000 IU per day for one year | 24 | Placebo | 25 | Objective and subjective symptom reduction | 1 year |

| Yang, 2015 [26] | Open-label RCT | 340 included→ 172 with vitamin D deficiency | Alfacalcidol 0.25 mcg twice a day for 24 weeks | 84 | Placebo | 88 | RA flare (DAS-28 > 3.2) | 6 months |

| Study | Outcome | Intervention | Controls | p-Value (Intervention vs. Controls) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | End of Treatment | Difference from Baseline | Baseline | End of Treatment | Difference from Baseline | |||

| Vitamin E | ||||||||

| Aryaeian et al. [14] | DAS-28 | 4.59 (1.11) | NR | −0.77 (0.91) † | 4.35 (0.95) | NR | −0.31 (0.98) | >0.05 |

| VAS pain (cm) | 4.02 (2.89) | NR | −0.64 (1.63) | 5.11 (2.44) | NR | −0.77 (3.31) | >0.05 | |

| SJC (n) | 6.71 (9.67) | NR | −2.62 (9.94) † | 6.45 (8.89) | NR | −1.05 (7.74) | >0.05 | |

| TJC (n) | 3.76 (4.88) | NR | −1.29 (5.84) † | 2.86 (1.67) | NR | −0.68 (2.34) | >0.05 | |

| Morning stiffness (hour) | 1.09 (0.89) | NR | −0.66 (1.11) † | 1.27 (0.77) | NR | −0.05 (0.86) | >0.05 | |

| Edmonds et al. [15] | Ritchie’s index | 15.9 (7.7) | 15.3 (10.0) | NR | 14.9 (8.8) | 14.0 (12.1) | NR | >0.05 |

| Morning stiffness (min) | 45 | 30 | NR | 30 | 20 | NR | >0.05 | |

| SJC (n) | 9.2 (3.4) | 9.9 (5.0) | NR | 9.8 (5.4) | 10.2 (5.6) | NR | >0.05 | |

| VAS pain (cm) | 4.63 (2.86) | NR | −0.56 (1.53) | 3.74 (2.92) | NR | +0.54 (1.12) | 0.006 | |

| Vitamin K | ||||||||

| Shishavan et al. [16] | DAS-28 | NR | NR | −12.56% † | NR | NR | NR | >0.05 |

| Folic acid | ||||||||

| Stamp et al. [17] | DAS-28 | 3.5; range (2.4; 5.9) | NR | −0.13; 95% CI [−0.69; 0.43] | 3.8; range [2.6; 5.8] | NR | −0.25; 95% CI [−0.87; 0.37] | 0.78 |

| Morgan et al. [18] | Joint indices for tenderness (n, min;max) | 5 mg: 32 (6; 112) 27.5 mg: 34 (2;105) | 5 mg: 21 (0; 90) † 27.5 mg: 14 (2; 41) † | NR | 34 (2; 99) | 18 (4; 62) † | NR | >0.05 >0.05 |

| Joint indices for swelling (n, min;max) | 5 mg: 51 (14; 85) 27.5 mg: 43 (18;103) | 5 mg: 14 (2; 41) † 27.5 mg: 13 (1; 58) † | NR | 45 (6; 85) | 12 (0; 51) † | NR | >0.05 >0.05 | |

| HAQ (value, min;max) | 5 mg: 2 (1; 3.8) 27.5 mg: 2 (1.1; 3.4) | 5 mg: 1.2 (1; 2.8) † 27.5 mg: 1.2 (1; 2.6) † | NR | 1.8 (1; 3.4) | 1.5 (1; 2.8) † | NR | >0.05 >0.05 | |

| Vitamin D | ||||||||

| Soubrier et al. [19] | DAS-28 | 3.69 (0.96) | 3.03 (1.1) | NR | 3.76 (0.68) | 3.37 (0.90) | NR | >0.05 |

| VAS pain (cm) | 3.61 (1.64) | 3.76 (2.39) | NR | 3.76 (2.39) | 3.81 (2.21) | NR | >0.05 | |

| HAQ | NR | NR | −0.03 (0.23) | NR | NR | +0.08 | 0.11 | |

| ESR (mm/h) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.002 * | |

| C-reactive protein | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.04 * | |

| Li et al. [20] | VAS pain (cm) | 22-Oxa: 6.1 (0.59) Calcitriol: 5.8 (0.62) | 22-Oxa: 5.2 (0.81) † Calcitriol: 5.04 (0.51) † | NR | 5.9 (0.52) | 5.89 (0.53) | NR | 22-Oxa: <0.05 Calcitriol: <0.05 |

| HAQ | 22-Oxa: 1.33 (0.77) Calcitriol: 1.34 (0.79) | 22-Oxa: 1.15 (0.1) † Calcitriol: 1.19 (0.28) † | NR | 1.31 (0.75) | 1.29 (0.83) | NR | 22-Oxa: <0.05 Calcitriol: >0.05 | |

| Morning stiffness (mn) | 22-Oxa: 146 (13) Calcitriol: 141 (12) | 22-Oxa: 115 (15) † Calcitriol: 105 (14) † | NR | 135 (15) | 130 (17) † | NR | 22-Oxa: <0.05 Calcitriol: <0.05 | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 22-Oxa: 15.72 (1.89) Calcitriol: 16.01 (1.98) | 22-Oxa: 17.85 (1.09) Calcitriol: 17.92 (1.11) | NR | 15.43 (1.53) | 15.92 (4.56) | NR | 22-Oxa: <0.05 Calcitriol: <0.05 | |

| Dehghan et al. [21] | Flares, n (%) | NA | 7/40 (17.5%) | NA | NA | 11/40 (27.5%) | NA | 0.42 |

| Salesi et al. [22] | DAS-28 | 5.4 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.2) | NR | 5.5 (1.3) | 4.7 (2.1) | NR | >0.05 |

| VAS pain (cm) | 6.26 (1.8) | 4.57 (1.99) | NR | 6.13 (2.18) | 3.87 (2.04) | NR | >0.05 | |

| TJC (n) | 11.9 (5.8) | 7.1 (5.1) | NR | 12.8 (6.1) | 9.2 (4.7) | NR | >0.05 | |

| SJC (n) | 2.7 (3.7) | 1.1 (2.7) | NR | 3.6 (4.4) | 2.1 (3.2) | NR | >0.05 | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 42.8 (11.2) | 50 (9.0) | NR | 37.2 (13.2) | 39.4 (12) | NR | <0.05 | |

| ESR (mm/h) | 35.8 (19) | 26.2 (16.8) | NR | 34.1 (18) | 27.6 (17.3) | NR | >0.05 | |

| Gopinath et al. [23] | Time to achieve pain relief (days) | NA | 21; range [7; 90] | NA | NA | 21; range [7; 90] | NA | 0.415 |

| % patients with reduction in VAS pain | NA | 50; range [0; 100] | NA | NA | 30; range [0; 30] | NA | 0.006 | |

| Hansen et al. [24] | DAS-28 | 2.8; 95% CI [2.1; 3.3] | 3.0; 95% CI [2.3; 3.8] | NR | 2.7; 95% CI [2.1–3.3] | 3.0; 95% CI [2.2; 3.7] | NR | 0.96 |

| VAS pain (cm) | 2.9; 95% CI [1.8; 3.7] | 3.9; 95% CI [2.6; 5.2] | NR | 2.9; 95% CI [1.8; 4.1] | 2.4; 95% CI [1.1; 3.7] | NR | 0.03 | |

| HAQ | 0.6; 95% CI [0.4; 0.9] | 0.7; 95% CI [0.4; 1] | NR | 0.6; 95% CI [0.4; 0.9] | 0.4; 95% CI [0.2; 0.7] | NR | 0.09 | |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 25 (24) | 30 (11) | NR | 21 (9) | 23 (11) | NR | <0.05 | |

| Brohult et al. [25] | Symptom reduction | NA | 16/24 (67%) | NA | NA | 8/25 (36%) | NA | 0.01 |

| Yang et al. [26] | Flares, n (%) | NA | 16/84 (19%) | NA | NA | 26/88 (29.5%) | NA | 0.11 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, Y.; Sigaux, J.; Letarouilly, J.-G.; Sanchez, P.; Czernichow, S.; Flipo, R.-M.; Soubrier, M.; Semerano, L.; Seror, R.; Sellam, J.; et al. Efficacy of Oral Vitamin Supplementation in Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2021, 13, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13010107

Nguyen Y, Sigaux J, Letarouilly J-G, Sanchez P, Czernichow S, Flipo R-M, Soubrier M, Semerano L, Seror R, Sellam J, et al. Efficacy of Oral Vitamin Supplementation in Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2021; 13(1):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13010107

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Yann, Johanna Sigaux, Jean-Guillaume Letarouilly, Pauline Sanchez, Sébastien Czernichow, René-Marc Flipo, Martin Soubrier, Luca Semerano, Raphaèle Seror, Jérémie Sellam, and et al. 2021. "Efficacy of Oral Vitamin Supplementation in Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials" Nutrients 13, no. 1: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13010107

APA StyleNguyen, Y., Sigaux, J., Letarouilly, J.-G., Sanchez, P., Czernichow, S., Flipo, R.-M., Soubrier, M., Semerano, L., Seror, R., Sellam, J., & Daïen, C. (2021). Efficacy of Oral Vitamin Supplementation in Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients, 13(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13010107