The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Change in Health Behaviors

2.2.2. Stress

2.2.3. Financial Stress

2.2.4. Food Insecurity

2.2.5. Current Level of Health Behaviors among Parents and Children

2.2.6. Qualitative Questions on COVID-19

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Family Characteristics and Current Health Behaviors

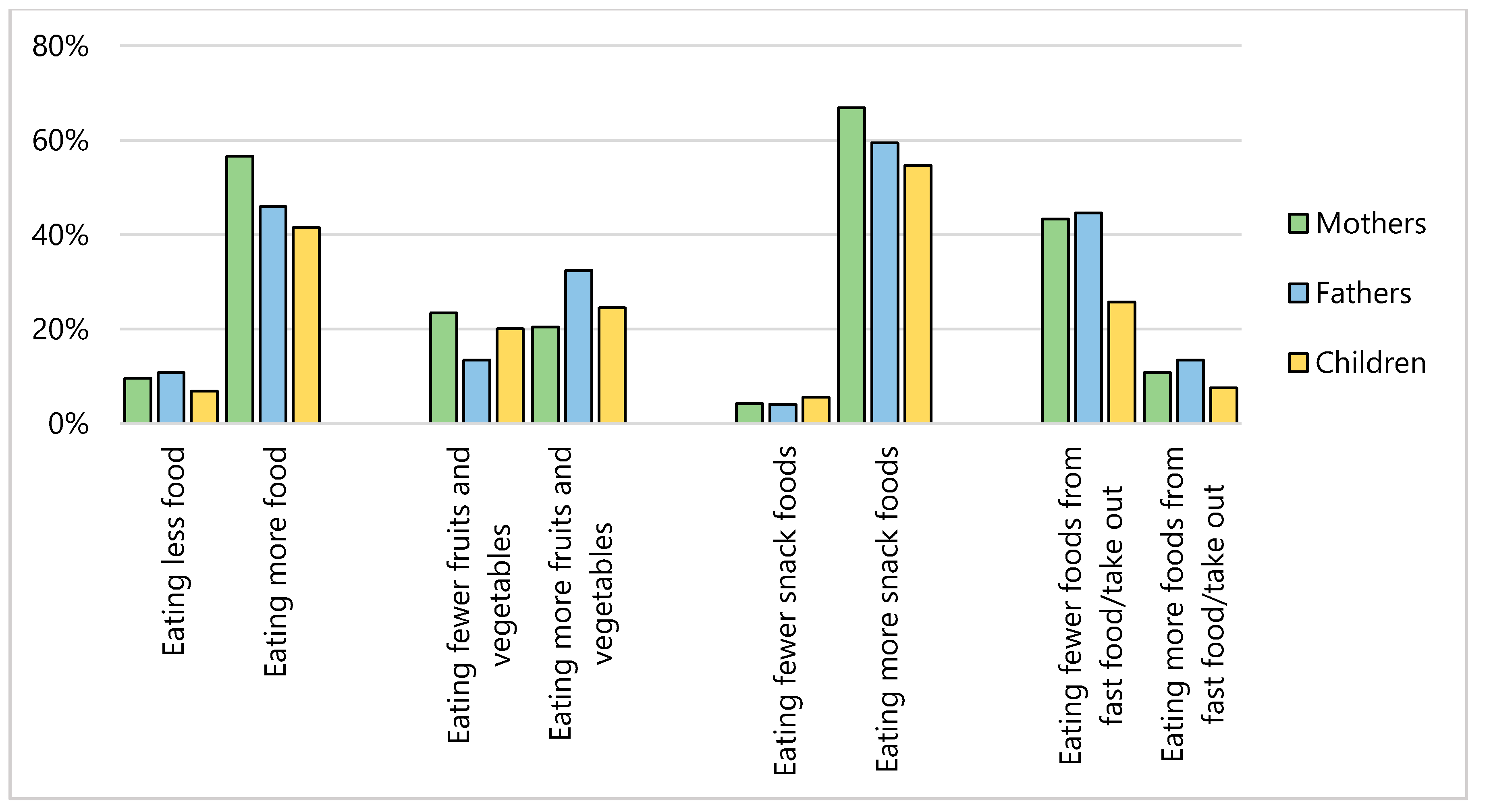

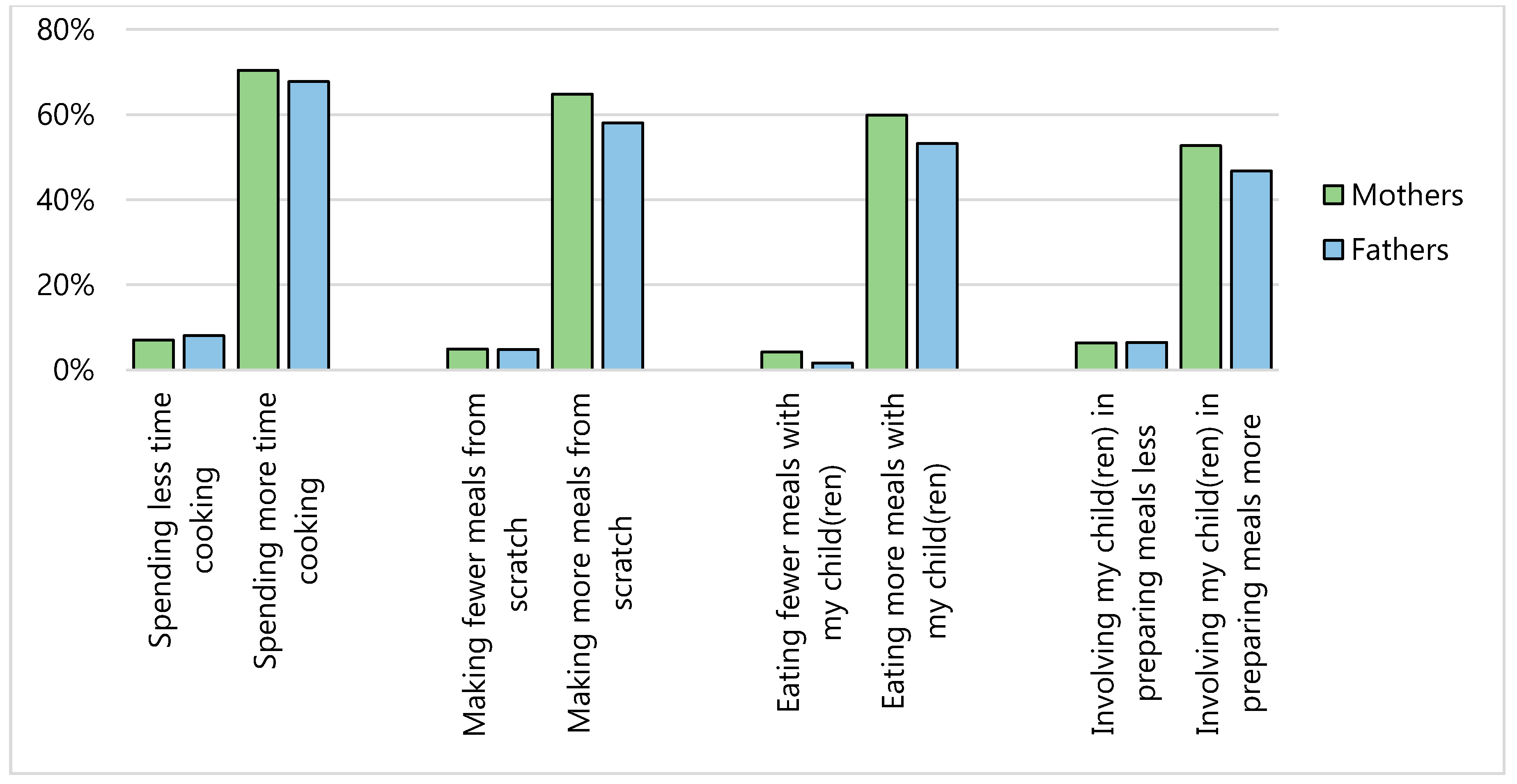

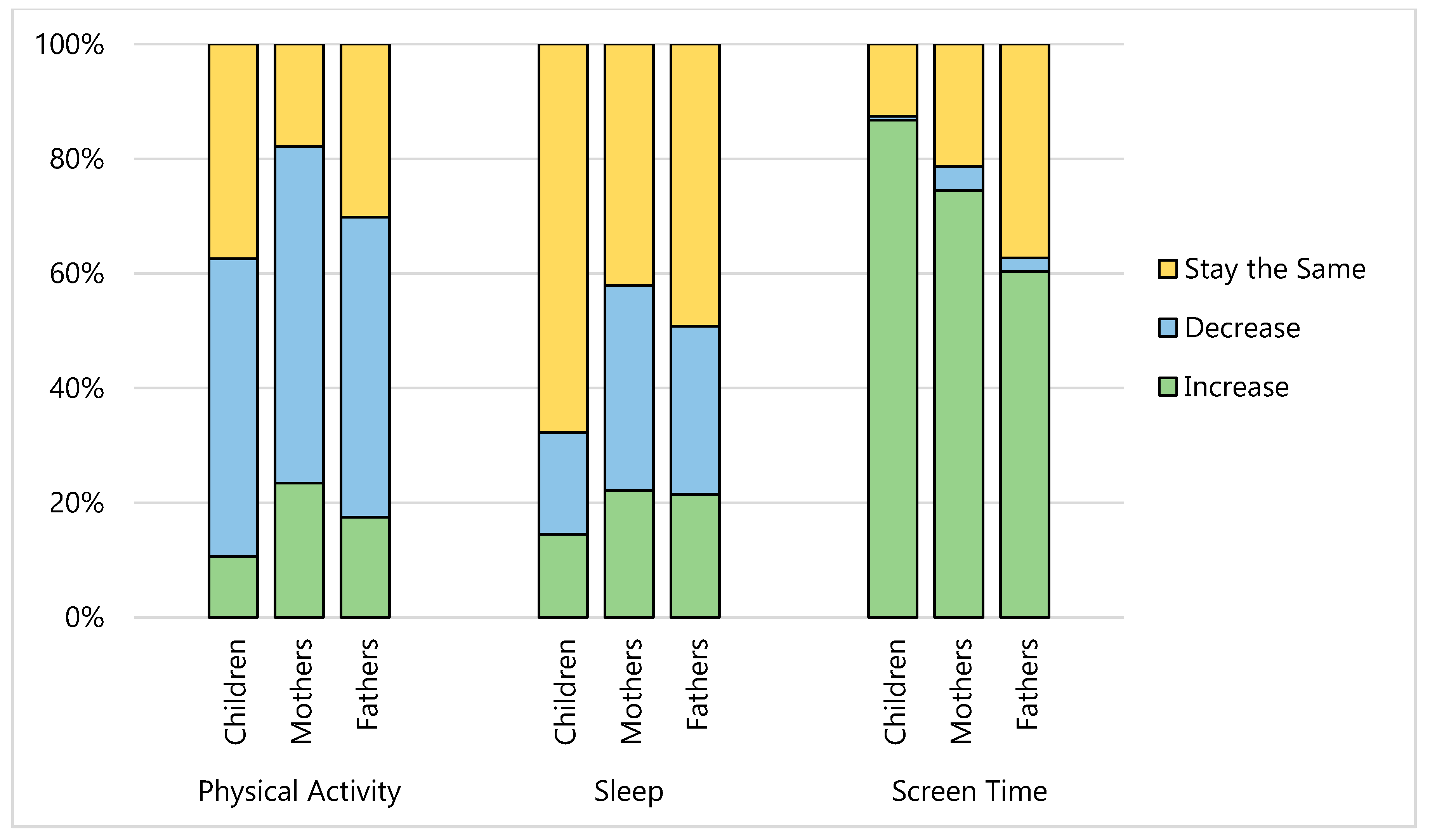

3.2. Change in Health Behaviors Since COVID-19

3.3. Family Stress, Financial and Food Security

3.4. Qualitative Questions on COVID-19

3.4.1. Physical Activity and Screen Time Changes

3.4.2. Children’s Mood and General Behavior

3.4.3. Factors that Increase Family Stress

3.4.4. Strategies to Cope with Changes

3.4.5. Helpful Resources

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Von Hippel, P.T.; Powell, B.; Downey, D.B.; Rowland, N.J. The effect of school on overweight in childhood: Gain in body mass index during the school year and during summer vacation. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banno, M.; Harada, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Tobita, R.; Tsujimoto, H.; Tsujimoto, Y.; Kataoka, Y.; Noda, A. Exercise can improve sleep quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Consumers Prepare for COVID-19. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/62f0014m/62f0014m2020004-eng.htm (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- The Suburban. COVID-19 Isolation Causing an Inevitable Rise in Screen Time. Available online: http://www.thesuburban.com/life/lifestyles/covid-19-isolation-causing-an-inevitable-rise-in-screen-time/article_43304486-697e-5403-86e8-5552b0262aca.html (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Moore, S.A.; Faulkner, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Brussoni, M.; Chulak-Bozzer, T.; Ferguson, L.J.; Mitra, R.; O’Reilly, N.; Spence, J.C.; Vanderloo, L.M.; et al. Impact of the COVID-19 virus outbreak on movement and play behaviours of Canadian children and youth: A national survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrobelli, A.; Pecoraro, L.; Ferruzzi, A.; Heo, M.; Faith, M.; Zoller, T.; Antoniazzi, F.; Piacentini, G.; Fearnbach, S.; Heymsfield, S. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown on Lifestyle Behaviors in Children with Obesity Living in Verona, Italy: A Longitudinal Study. Obesity 2020. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Roso, M.; De Carvalho Padilha, P.; Mantilla-Escalante, D.; Ulloa, N.; Brun, P.; Acevedo-Correa, D.; Martorell, M.; Aires, M.; Carrasco-Marín, F.; Paternina-Sierra, K.; et al. Covid-19 Confinement and Changes of Adolescent’s Dietary Trends in Italy, Spain, Chile, Colombia and Brazil. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morneau Shepell. The Mental Health Index report: Spotlight on the mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Available online: https://www.morneaushepell.com/sites/default/files/assets/permafiles/92440/mental-health-index-report-apr-2020.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Hruska, V.; Ambrose, T.; Darlington, G.; Ma, D.W.L.; Haines, J.; Buchholz, A.C.; Guelph Family Health Study. Family-based stress is associated with adiposity in parents of preschoolers. Obesity 2020, 28, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, L.M.; Darlington, G.; Haines, J.; Ma, D.W.L. Examination of associations between chaos in the home environment, serum cortisol level, and dietary fat intake among parents of preschool-age children. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bates, C.R.; Buscemi, J.; Nicholson, L.M.; Cory, M.; Jagpal, A.; Bohnert, A.M. Links between the organization of the family home environment and child obesity: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graignic-Philippe, R.; Dayan, J.; Chokron, S.; Jacquet, A.Y.; Tordjman, S. Effects of prenatal stress on fetal and child development: A critical literature review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 43, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, J.; Douglas, S.; Mirotta, J.A.; O’Kane, C.; Breau, R.; Walton, K.; Krystia, O.; Chamoun, E.; Annis, A.; Darlington, G.A.; et al. Guelph Family Health Study. Guelph Family Health Study: Pilot study of a home-based obesity prevention intervention. Can. J. Public Health 2018, 109, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, E.P.; Kumanyika, S.; Moore, R.H.; Stettler, N.; Wrotniak, B.H.; Kazak, A. Influence of stress in parents on child obesity and related behaviors. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1096–e1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boushey, H.; Gundersen, B. When Work Just isn’t Enough: Measuring Material Hardships Faced by Families After Moving from Welfare to Work. BRIEFING Paper; EPI: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED457249.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Gundersen, C.; Engelhard, E.E.; Crumbaugh, A.S.; Seligman, H.K. Brief assessment of food insecurity accurately identifies high-risk US adults. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1367–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHANES National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Dietary Screener Questionnaire. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2009-2010/DTQ_F.htm (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- IPAQ International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Downloadable questionnaires. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/questionnaire_links (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Taveras, E.M.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Oken, E.; Gunderson, E.P.; Gillman, M.W. Short sleep duration in infancy and risk of childhood overweight. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008, 162, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C.; Daniels, S.R. Parental report of outdoor playtime as a measure of physical activity in preschool-aged children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Darlington, G.; Ma, D.W.L.; Haines, J.; Guelph Family Health Study. Mothers’ and fathers’ media parenting practices associated with young children’s screen-time: A cross-sectional study. BMC Obes. 2018, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, N.; Viner, R.M. Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripicchio, G.L.; Kachurak, A.; Davey, A.; Bailey, R.L.; Dabritz, L.J.; Fisher, J.O. Associations between Snacking and Weight Status among Adolescents 12-19 Years in the United States. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Navigator USA. From Scratch Cooking to Home Baking: What Coronavirus-Fueled Trends Could Linger Post-Pandemic? Available online: https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2020/04/13/From-scratch-cooking-to-home-baking-What-coronavirus-fueled-trends-could-linger-post-pandemic (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Larson, N.I.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Hannan, P.J.; Story, M. Family meals during adolescence are associated with higher diet quality and healthful meal patterns during young adulthood. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1502–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Stress in America 2019. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2019/stress-america-2019.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- American Psychological Association. Stress in America 2020: Stress in the Time of COVID-19, Volume 1. Available online: https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/stress-in-america-covid.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Panahi, Y.; Sahraei, H.; Johnston, T.P.; Sahebkar, A. The impact of stress on body function: A review. EXCLI J. 2017, 16, 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salleh, M.R. Life Event, Stress and Illness. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2008, 15, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- PROOF. Household Food Insecurity in Canada. Available online: https://proof.utoronto.ca/food-insecurity/#2 (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Global News. Food banks’ demand surges amid COVID-19. Now they worry about long term pressures. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/6816023/food-bank-demand-covid-19-long-term-worry/ (accessed on 28 June 2020).

- FSIN Food Security Information Network. Global Report on Food Crises. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/publications/2020-global-report-food-crises (accessed on 28 June 2020).

- Rohwerder, B. Secondary Impacts of Major Disease Outbreaks in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e6237e6e90e077e3b483ffa/756_Secondary_impacts_of_major_disease_outbreak__in_low_income_countries.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

| Variables | Household | Children | Mothers | Fathers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 254) | (n = 310) | (n = 235) | (n = 126) | |

| Age, Years, Mean (SD) | - | 5.7 (2.0) | 37.5 (4.8) | 39.4 (5.5) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) 1 | ||||

| Caucasian | - | - | 204 (86.8) | 111 (88.1) |

| African American | - | - | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Latin American | - | - | 7 (3.0) | 3 (2.4) |

| Asian | - | - | 11 (4.7) | 5 (4.0) |

| South/West Asian | - | - | 7 (3.0) | 4 (3.2) |

| Other | - | - | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.8) |

| Household Income, n (%) 2 | ||||

| Less than $30,000 | 13 (5.1) | - | - | - |

| $30,000-$59,999 | 25 (9.8) | - | - | - |

| $60,000-$99,999 | 55 (21.7) | - | - | - |

| $100,000 or more | 144 (56.7) | - | - | - |

| Marital Status, n (%) 3 | ||||

| Single | - | - | 7 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cohabiting | 23 (9.8) | 14 (11.1) | ||

| Married | - | - | 195 (83.0) | 104 (82.5) |

| Separated | - | - | 8 (3.4) | 1 (0.8) |

| Physical Activity, Mean (SD) 4 | ||||

| MVPA, hours/week | - | - | 4.5 (4.2) | 9.5 (13.4) |

| Time spent walking, hours/week | - | - | 4.5 (5.1) | 6.1 (8.5) |

| Time spent sitting, hours/day | - | - | 6.1 (2.9) | 6.5 (3.1) |

| Time spent outdoors, hours/day | - | 1.1 (0.5) | - | - |

| Time in active play, hours/day | - | 0.9 (0.5) | - | - |

| Sleep Duration, Mean (SD) | ||||

| Hours | - | 10.9 (0.7) | 8.2 (1.1) | 7.9 (0.9) |

| Screen Time, Mean (SD) | ||||

| Hours/day | - | 2.4 (1.6) | 2.7 (1.6) | 2.8 (1.7) |

| Eating Patterns, Mean (SD) | ||||

| Fruit and Vegetable, times/day | - | 4.5 (2.2) | 4.1 (2.1) | 3.8 (2.2) |

| Snack Foods, times/day | - | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.9) | 0.9 (0.9) |

| Fast Food/Take-Out, times/week | - | - | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.7) |

| Variables | Children (n = 310) | Mothers (n = 235) | Fathers (n = 126) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress Level 1-10, Mean (SD) | - | 6.8 (1.9) | 6.0 (2.5) |

| Child Concern COVID-19, n (%) 1 | |||

| Very little | 153 (49.4) | - | - |

| Somewhat | 117 (37.7) | - | - |

| Very Much | 22 (7.1) | - | - |

| Financial Stress, n Yes (%) | |||

| During the past month | - | 45 (19.1) | 17 (13.5) |

| Over the next 6 months | - | 51 (21.7) | 22 (17.5) |

| Food Insecurity, n Yes (%) | |||

| During the past month | - | 20 (8.5) | 6 (4.8) |

| Over the next 6 months | - | 20 (8.5) | 6 (4.8) |

| Resources on | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Increasing physical activity | “More exercise activities for inside…that last for around 1/2 hr.” “Resources around fun physical activity they can do indoors, or challenges they can participate in” |

| Reducing screen time | “ Ideas to get the kids off screens”“Any tips for keeping a 4-year-old independently busy (and not on a screen) while mommy gets work done would be great too!!” |

| Homeschooling | “Having a better way to ease [daughter] into her homework would have helped at first to minimize the appearance of a school-related pressure one encounters as a parent at first.” |

| Time management | “I’m trying to figure out the balancing helping with school work and working myself fulltime.” “More ready-to-go day plans for pre-school aged children.” |

| Parenting | “We could use some support around managing tantrums and fighting between siblings.” |

| Grocery shopping | “How to plan ahead and minimize the trips to the grocery store?” “Ideally I’d like to only go every 2 weeks, but don’t know how to stretch out fresh produce to last that long.” |

| Cooking and diet | “Meal planning tools and trackers for the # of servings of healthy foods we eat each day vs. the # of unhealthy snacks or “treats”” “Activity ideas to help get (child’s name) interested in helping in the kitchen” |

| Understanding COVID-19 | “How to talk to kids about not being able to do things they look forward to ie. seeing grandparents, having a birthday party, playing with friends.” “Kids directed video about Corona virus, I didn’t realize he was so worried until I asked him while doing the questionnaire. I talk with him about it often, in a non-scary way.” |

| Improving mental health | “Mindfulness activities or other stress-reduction methods, appropriate for all ages.” “Ideas for emotional regulation” “We need supports on how to support the kid’s anxiety during this time.” |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carroll, N.; Sadowski, A.; Laila, A.; Hruska, V.; Nixon, M.; Ma, D.W.L.; Haines, J.; on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352

Carroll N, Sadowski A, Laila A, Hruska V, Nixon M, Ma DWL, Haines J, on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients. 2020; 12(8):2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarroll, Nicholas, Adam Sadowski, Amar Laila, Valerie Hruska, Madeline Nixon, David W.L. Ma, Jess Haines, and on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. 2020. "The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children" Nutrients 12, no. 8: 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352

APA StyleCarroll, N., Sadowski, A., Laila, A., Hruska, V., Nixon, M., Ma, D. W. L., Haines, J., & on behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients, 12(8), 2352. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352