Effect of Experiential Vegetable Education Program on Mediating Factors of Vegetable Consumption in Australian Primary School Students: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Does the vegetable education program improve primary school students’ knowledge, verbalization ability, vegetable acceptance, behavioural intentions, willingness to try vegetables and number of new vegetables consumed?

- Does a high-intensity training of teachers result in a greater effect of the vegetable education program than a low-intensity training of teachers?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.1.1. Intervention

- Intervention low: VERTICAL vegetable education intervention with low-intensity teacher training (online and written materials).

- Intervention high: VERTICAL vegetable education intervention with high-intensity teacher training (as for ‘intervention low’ but with face-to-face training of teachers).

- Control: regular school curriculum (with VERTICAL training and materials provided post-study).

Teacher Training

Vegetable Education Program

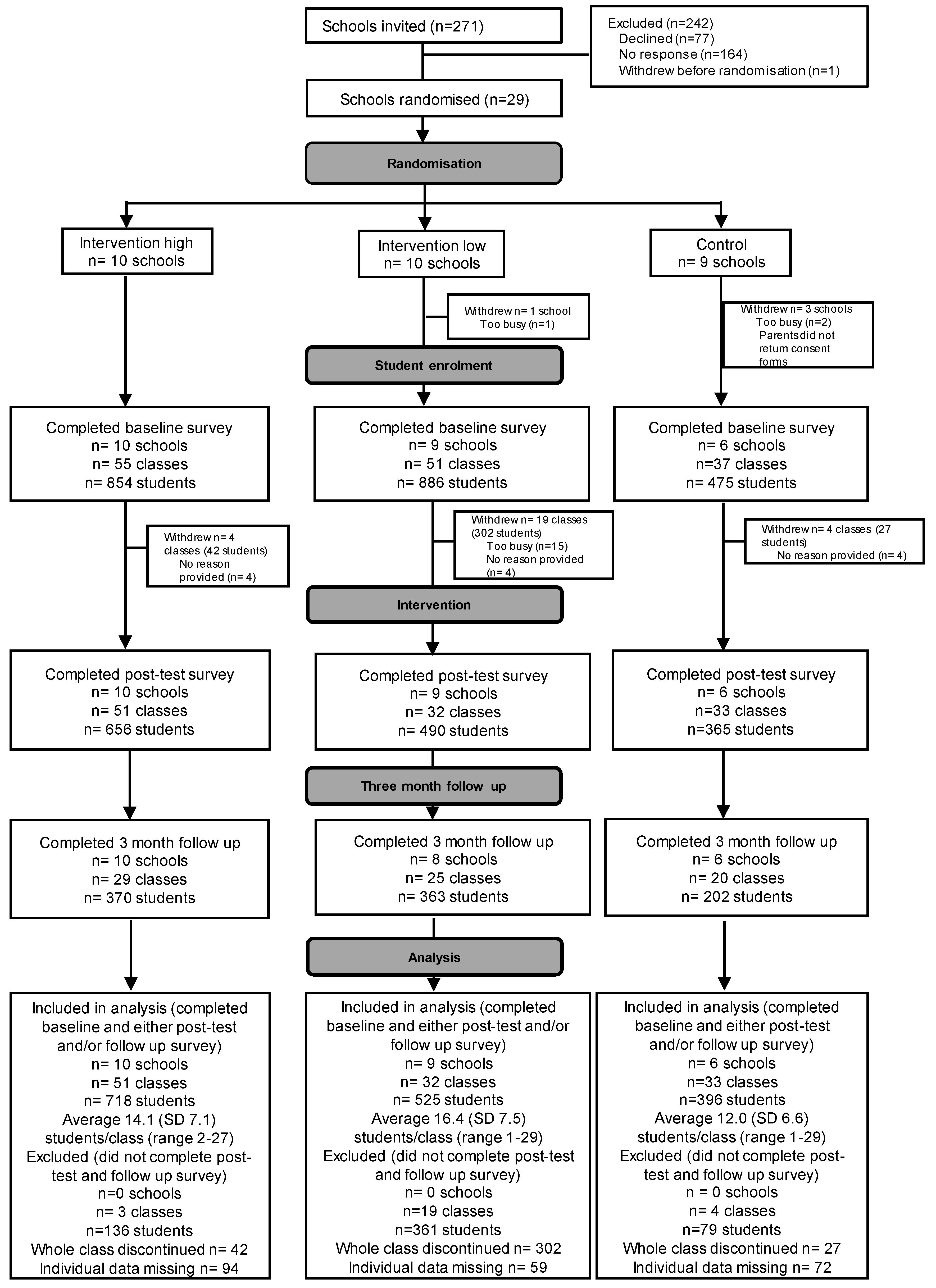

2.1.2. Participants and Recruitment

2.2. Outcome Measures

2.2.1. Primary Outcome Measures

- Knowledge: knowledge was tested in relation to vegetables and the senses involved in eating and drinking. A combination of multiple-choice questions, true/false statements and open questions was used.

- Verbalization: ability to verbalize sensory perceptions was tested. Children were asked to provide descriptive words for two vegetables.

- Acceptance: acceptance for vegetables was measured as a single item using an age-appropriate 7-point hedonic facial scale [36]. In addition, acceptance for six specific vegetables, which varied between year levels, was measured using the same scale. Examples to ensure correct understanding of the scale were given.

- Behavioural intention: behavioural intentions for eating a variety of foods and vegetables was measured using four statements and 5-point Likert scales. Format and response categories were according to the validated scales of behavioural intent from the Theory of Planned Behaviour [37].

- Willingness to try: willingness to try (yes/no) four specific (less commonly consumed) vegetables was measured using pictures of the vegetables.

- Number of new vegetables tried: students were asked to record the number of new vegetables they had tried in the previous month.

2.2.2. Secondary Outcomes and Other Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Sample Size Calculation/Power

2.3.2. Data Coding

- Knowledge: A sum score was calculated. A total of 11 points for knowledge could be scored. For all questions, a correct response provided a score of 1 point, with exception of an open question about listing vegetables, where up to 2 points could be scored (year 3–4: 0 correct = 0 points, 1–3 correct = 1 points, 4 or more correct is 2 points; year 5–6: 0 correct = 0 points, 1 correct = 1 point, 2 or more correct = 2 points). Cut-offs were determined based on the results from a pilot study [34].

- Verbalization: The number of descriptive (e.g., crunchy, sweet) words was counted. Hedonic words (e.g., delicious, yummy) were excluded. One point was allocated for each correct answer. The number of descriptive terms summed across the two vegetables was calculated.

- Acceptance: Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to determine internal consistency of individual items to the overall concept and was satisfactory (0.75). An average score across all items was calculated.

- Behavioural intention: Cronbach’s alpha was calculated and was satisfactory (0.80). The mean of these items was calculated.

- Willingness to try: A sum score was calculated with one point allocated for each vegetable the child was willing to try.

- Number of new vegetables tried: the number of new vegetables the student recorded.

2.3.3. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

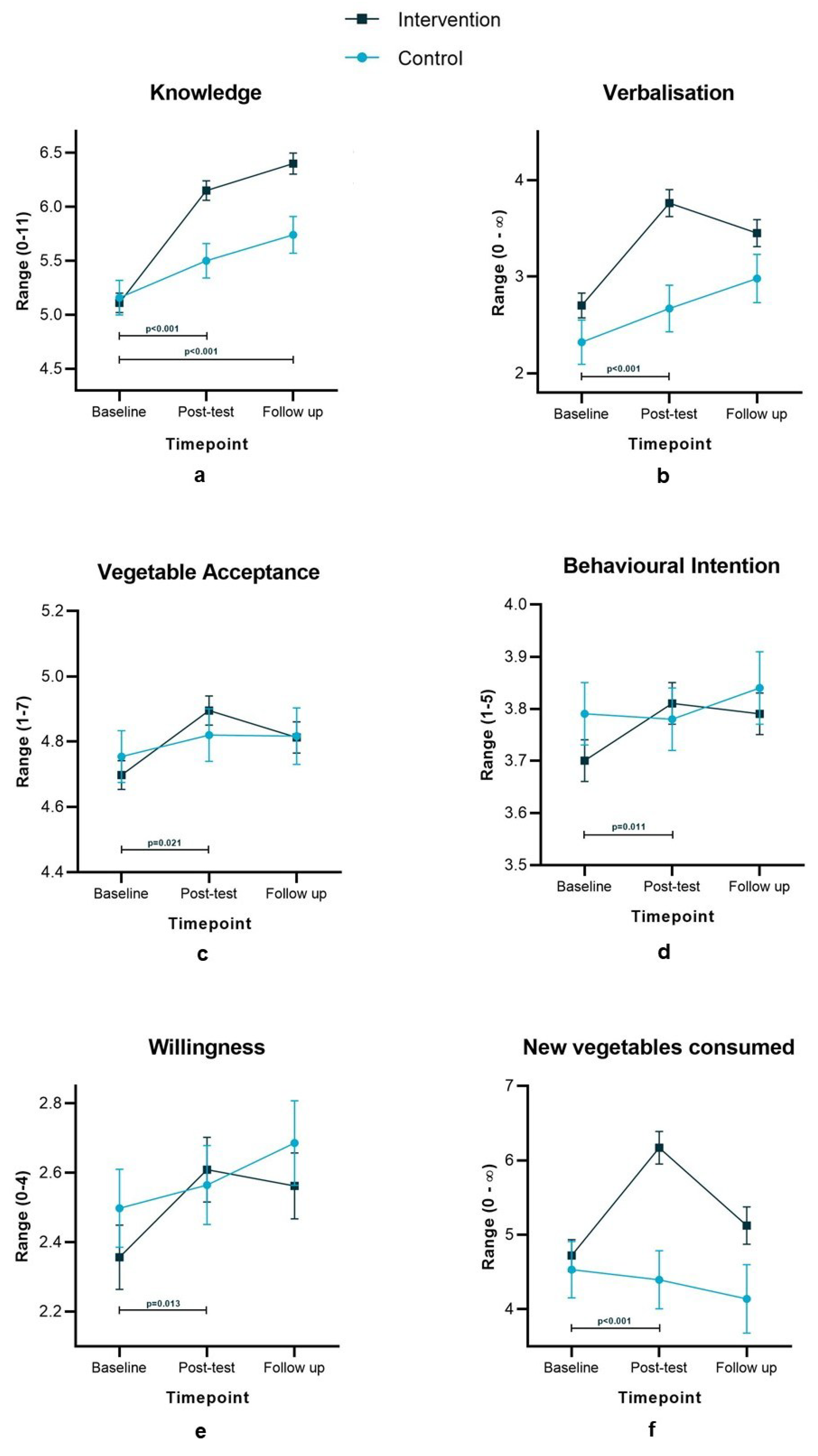

3.2. Outcome Measures

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Description of VERTICAL Program and Materials

- Fully written lesson plans with objectives, materials needed and suggested lesson activities. Lessons contain student worksheets and are supported by interactive whiteboard materials.

- An online teacher training module with information on program objectives and structure, theoretical background about the senses and food preference development and practical information to implement the program in the school and information.

- An implementation manual which contains the information in the training module in some more detail, and additionally provides resources for implementation of the program (e.g., shopping lists) and information on curriculum alignment.

| Number | Title | Main Topic Studied |

|---|---|---|

| Lower (Foundation–Year 2) | ||

| 1 | The Five Senses | Students learn about the senses involved in eating and describe vegetables in terms of the five senses. |

| 2 | From Seed to Vegetable | Students discover and eat different parts of vegetable plants. |

| 3 | The Basic Tastes | Students can recognise the four basic tastes and can identify the dominant taste in different vegetables. |

| 4 | Becoming a Food Adventurer | Students learn that liking of foods can change by trying and become more open to taste novel foods. |

| 5 | Picnic in Class: Sandwich | Students prepare and enjoy eating a sandwich with vegetables together. |

| Middle (Year 3–4) | ||

| 1 | Discover Vegetables through the Senses | Students become aware of individual differences in vegetable preferences through tasting vegetables. |

| 2 | Vegetables Grow in Different Climates | Students discover and eat vegetables from different climatic regions. |

| 3 | Preparing Vegetables—a Science Experiment | Students investigate the role of cooking on taste/texture of vegetables through a simple science experiment. |

| 4 | Perfectly Imperfect Vegetables | Student learn how visual cues can affect our food choices and try to convince someone to try an imperfect vegetable. |

| 5 | MasterChef® in Class: the Salad | Students prepare, evaluate and enjoy eating a salad with vegetables together. |

| Upper (Year 5–6) | ||

| 1 | How our Senses Interact | Students discover how our senses interact when we eat foods. |

| 2 | A Science Experiment on Taste of Vegetables | Students understand the different elements of a scientific investigation by planning and conducting an experiment on the taste of vegetables. |

| 3 | Vegetables from Farm to Plate | Students investigate the role of food technology in producing vegetable products. |

| 4 | Vegetables and Cultural Diversity | Students understand how cultural background shapes food preferences from an early age. |

| 5 | The Vegetable Dip Challenge | Students prepare, evaluate and enjoy eating vegetable dips together. |

References

- Mihrshahi, S.; Myton, R.; Partridge, S.R.; Esdaile, E.; Hardy, L.L.; Gale, J. Sustained low consumption of fruit and vegetables in Australian children: Findings from the Australian National Health Surveys. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2019, 30, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed.; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Wang, X.; Ouyang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Bao, W.; Hu, F.B. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: Systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2014, 349, g4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blissett, J.; Fogel, A. Intrinsic and extrinsic influences on children’s acceptance of new foods. Physiol. Behav. 2013, 121, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklaus, S.; Boggio, V.; Issanchou, S. Food choices at lunch during the third year of life: High selection of animal and starchy foods but avoidance of vegetables. Acta Paediast. 2005, 94, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, A.A.M.; Delahunty, C.M.; de Graaf, C. Vegetables and other core food groups: A comparison of key flavour and texture properties. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L. Development of food preferences. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1999, 19, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCosta, P.; Møller, P.; Frøst, M.B.; Olsen, A. Changing children’s eating behaviour—A review of experimental research. Appetite 2017, 113, 327–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekitsing, C.; Hetherington, M.M.; Blundell-Birtill, P. Developing healthy food preferences in preschool children through taste exposure, sensory learning, and nutrition education. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2018, 7, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C.; Scholtens, P.A.; Lalanne, A.; Weenen, H.; Nicklaus, S. Development of healthy eating habits early in life. Review of recent evidence and selected guidelines. Appetite 2011, 57, 796–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmont-Rossé, C.; Drabek, R.; Almli, V.L.; van Zyl, H.; Silva, A.P.; Kern, M.; McEwan, J.A.; Ares, G. A cross-cultural perspective on feeling good in the context of foods and beverages. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werle, C.O.; Trendel, O.; Ardito, G. Unhealthy food is not tastier for everybody: The “healthy = tasty” French intuition. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunathan, R.; Naylor, R.W.; Hoyer, W.D. The unhealthy = tasty intuition and its effects on taste inferences, enjoyment, and choice of food products. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepper, M.J.; Chai, W. Parents’ barriers and strategies to promote healthy eating among school-age children. Appetite 2016, 103, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocock, M.; Trivedi, D.; Wills, W.; Bunn, F.; Magnusson, J. Parental perceptions regarding healthy behaviours for preventing overweight and obesity in young children: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, Å.; Berlin, A.; Sundblom, E.; Elinder, L.S.; Nyberg, G. Stuck in a vicious circle of stress. Parental concerns and barriers to changing children’s dietary and physical activity habits. Appetite 2015, 87, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharairi, N.A.; Somerset, S.M. Associations between Parenting Styles and Children’s Fruit and Vegetable Intake. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2015, 54, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, L.J.; Chambers, L.C.; Añez, E.V.; Wardle, J. Facilitating or undermining? The effect of reward on food acceptance. A narrative review. Appetite 2011, 57, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.E.; Christian, M.S.; Cleghorn, C.L.; Greenwood, D.C.; Cade, J.E. Systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to improve daily fruit and vegetable intake in children aged 5 to 12 y. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, D.A.; Cotton, W.G.; Peralta, L.R. Teaching approaches and strategies that promote healthy eating in primary school children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, L.R.; Dudley, D.A.; Cotton, W.G. Teaching healthy eating to elementary school students: A scoping review of nutrition education resources. J. Sch. Health 2016, 86, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.M.; Hemingway, A.; Rajska, J.; Hartwell, H. Repeated exposure and conditioning strategies for increasing vegetable liking and intake: Systematic review and meta-analyses of the published literature. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holley, C.E.; Farrow, C.; Haycraft, E. A systematic review of methods for increasing vegetable consumption in early childhood. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2017, 6, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennella, J.A.; Reiter, A.R.; Daniels, L.M. Vegetable and fruit acceptance during infancy: Impact of ontogeny, genetics, and early experiences. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 211S–219S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laureati, M.; Bergamaschi, V.; Pagliarini, E. School-Based intervention with children. Peer-Modeling, reward and repeated exposure reduce food neophobia and increase liking of fruits and vegetables. Appetite 2014, 83, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battjes-Fries, M.C.; Haveman-Nies, A.; van Dongen, E.J.; Meester, H.J.; van den Top-Pullen, R.; de Graaf, K.; van’t Veer, P. Effectiveness of Taste Lessons with and without additional experiential learning activities on children’s psychosocial determinants of vegetables consumption. Appetite 2016, 105, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battjes-Fries, M.C.; Haveman-Nies, A.; Zeinstra, G.G.; van Dongen, E.J.; Meester, H.J.; van den Top-Pullen, R.; van’t Veer, P.; de Graaf, K. Effectiveness of Taste Lessons with and without additional experiential learning activities on children’s willingness to taste vegetables. Appetite 2017, 109, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustonen, S.; Rantanen, R.; Tuorila, H. Effect of sensory education on school children’s food perception: A 2-year follow-up study. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustonen, S.; Tuorila, H. Sensory education decreases food neophobia score and encourages trying unfamiliar foods in 8–12-year-old children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverdy, C.; Schlich, P.; Köster, E.P.; Ginon, E.; Lange, C. Effect of sensory education on food preferences in children. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverdy, C.; Chesnel, F.; Schlich, P.; Köster, E.; Lange, C. Effect of sensory education on willingness to taste novel food in children. Appetite 2008, 51, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battjes-Fries, M.C.; Haveman-Nies, A.; Renes, R.-J.; Meester, H.J.; van ’t Veer, P. Effect of the Dutch school-based education programme Taste Lessons’ on behavioural determinants of taste acceptance and healthy eating: A quasi-experimental study. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 18, 2231–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, A.A.M.; Cochet-Broch, M.; Cox, D.N.; Vogrig, D. VERTICAL: A sensory education program for Australian primary schools to promote children’s vegetable consumption. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poelman, A.A.M.; Cochet-Broch, M.; Cox, D.N.; Vogrig, D. Vegetable education program positively affects factors associated with vegetable consumption among Australian primary (elementary) schoolchildren. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2033.0.55.001—Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/2033.2020.2055.0012016?OpenDocument (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Laureati, M.; Pagliarini, E.; Toschi, T.G.; Monteleone, E. Research challenges and methods to study food preferences in school-aged children: A review of the last 15 years. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 46, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1249.0–Australian Standard Classification of Cultural and Ethnic Groups (ASCCEG). 2016. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/allprimarymainfeatures/EFAAAA766091FE94CA2584D30012B99D?opendocument (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Cooke, L.; Carnell, S.; Wardle, J. Food neophobia and mealtime food consumption in 4–5-year old children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poelman, A.A.M.; Delahunty, C.M.; Broch, M.; de Graaf, C. Multiple vs. single target vegetable exposure to increase young children’s vegetable intake. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Mishra, G. Socio-Economic inequalities in women’s fruit and vegetable intakes: A multilevel study of individual, social and environmental mediators. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.K.; Piaggio, G.; Elbourne, D.R.; Altman, D.G. Consort 2010 statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012, 345, e5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.; Kypri, K.; Freund, M.; Hodder, R. Obtaining active parental consent for school-based research: A guide for researchers. Aust. N. J. Public Health 2009, 33, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, N.; Cardon, G.; De Craemer, M.; Hermans, N.; Renard, S.; Roesbeke, M.; Stevens, W.; De Lepeleere, S.; Deforche, B. Effect and process evaluation of a real-world school garden program on vegetable consumption and its determinants in primary schoolchildren. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, N.I.; te Velde, S.J.; Brug, J. Long-Term effects of the Dutch Schoolgruiten Project–promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among primary-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1213–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Delgado-Noguera, M.; Tort, S.; Martinez-Zapata, M.J.; Bonfill, X. Primary school interventions to promote fruit and vegetable consumption: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirin, S.R. Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 417–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Huon, G. An experimental investigation of the influence of health information on children’s taste preferences. Health Educ. Res. 2000, 15, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maimaran, M.; Fishbach, A. If It’s Useful and You Know It, Do You Eat? Preschoolers Refrain from Instrumental Food. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 642–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, R.W.; Taylor, J.A.; Gardner, A.; Van Scotter, P.; Powell, J.C.; Westbrook, A.; Landes, N. The BSCS 5E Instructional Model: Origins and Effectiveness; BSCS: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2006; pp. 88–98. [Google Scholar]

| Outcome | Number of Questions | Example of Question | Answer Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 11 | Which 5 senses are involved in eating vegetables? | Multiple Choice, True/False, Open question |

| Verbalization ability | 2 | How does this [vegetable] taste and feel in our mouth? Write as many describing words as you can. | Open question |

| Vegetable acceptance (0.75) | 7 | How much do you like [vegetable]? | From ‘Really dislike’ (=1) to ‘Really like’ (=7) |

| Behavioural intention (0.80) | 4 | I will eat a variety of vegetables. | From ‘No, definitely not’ (=1) to ‘Yes, definitely’ (=5) |

| Vegetables willing to try | 4 | Would you try [vegetable] if someone offered it to you? | Yes/No |

| New vegetables consumed | 1 | How many new vegetables have you consumed in the last month? | Number |

| Characteristics | Intervention High (n = 718) | Intervention Low (n = 526) | Control (n = 396) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 8.99 (1.53) | 9.18 (1.38) | 9.23 (1.43) |

| Gender (%) | |||

| Boy | 332 (47.2) | 258 (49.1) | 205 (51.8) |

| Girl | 386 (53.8) | 267 (50.9) | 191 (48.2) |

| Cultural background 1 | |||

| Australian/New Zealander | 281 (53.4) | 321 (71.0) | 197 (65.9) |

| Northern/Western European | 57 (10.8) | 43 (9.5) | 40 (13.4) |

| Southern/Eastern European | 31 (5.9) | 29 (6.4) | 13 (4.3) |

| North African/Middle Eastern | 18 (3.4) | 2 (0.4) | 7 (2.3) |

| South East Asian | 35 (6.7) | 13 (2.9) | 5 (1.7) |

| North East Asian | 19 (3.6) | 17 (3.8) | 13 (4.3) |

| Southern/Central Asian | 51 (9.7) | 12 (2.7) | 10 (3.3) |

| North/Central/South American | 13 (2.7) | 10 (2.2) | 2 (0.7) |

| Sub Saharan African | 5 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.3) |

| Other (not specified) | 16 (3.0) | 5 (1.1) | 8 (0.7) |

| Vegetable consumption, mean (SD) serves/day 1 | 1.63 (1.14) | 1.71 (1.16) | 1.79 (1.20) |

| Food neophobia, mean (SD) 1 | 14.30 (4.64) | 14.16 (4.69) | 13.70 (4.75) |

| Year level 2 | |||

| Lower | 193 (26.9) | 77 (14.7) | 87 (22.0) |

| Middle | 300 (41.8) | 273 (52.0) | 152 (38.4) |

| Upper | 225 (31.3) | 175 (33.3) | 157 (39.6) |

| SES 3 | |||

| Low | 211 (29.4) | 233 (44.4) | 52 (13.1) |

| Medium | 366 (51.0) | 173 (33.0) | 98 (24.7) |

| High | 141 (19.6) | 119 (22.7) | 246 (62.1) |

| State | |||

| NSW | 273 (38.0) | 189 (36.0) | 166 (41.9) |

| SA | 445 (62.0) | 336 (64.0) | 230 (58.1) |

| School size | |||

| <400 students | 545 (75.9) | 322 (61.3) | 90 (22.7) |

| 401–600 students | 173 (24.1) | 84 (16.0) | 196 (49.5) |

| >600 students | 0 (0) | 119 (22.7) | 110 (27.8) |

| Outcome | n | Effect (95% CI) | Bonferroni p | ICC Class/School |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 1627 | 0.109/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | −0.194 (−0.465 to 0.077) | 0.296 | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | −0.243 (−0.566 to 0.081) | 0.243 | ||

| Verbalization | 1639 | 0.077/0.008 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | −0.055 (−0.376 to 0.265) | 1.000 | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.003 (−0.382 to 0.387) | 1.000 | ||

| Vegetable acceptance | 1622 | 0.023/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | −0.047 (−0.178 to 0.084) | 1.000 | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | −0.113 (−0.269 to 0.043) | 0.284 | ||

| Behavioural intention | 1621 | 0.012/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | −0.075 (−0.191 to 0.041) | 0.425 | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | −0.139 (−0.276 to −0.001) | 0.046 * | ||

| Vegetables willing to try | 1621 | 0.011/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | 0.088 (−0.085 to 0.262) | 0.811 | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | −0.038 (−0.243 to 0.167) | 1.000 | ||

| New vegetables consumed | 1612 | 0.030/0.001 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | −0.315 (−1.311 to 0.681) | 1.000 | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.049 (−1.128 to 1.225) | 1.000 |

| Outcome | n | Effect (95% CI) | Bonferroni p | ICC Class/School |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 1627 | 0.113/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | 0.724 (0.482 to 0.966) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.732 (0.432 to 1.033) | <0.001 * | ||

| Verbalization | 1639 | 0.086/0.022 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | 0.709 (0.420 to 0.998) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.082 (−0.276 to 0.440) | 1.000 | ||

| Vegetable acceptance | 1622 | 0.030/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | 0.132 (0.016 to 0.248) | 0.021 * | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.053 (−0.092 to 0.197) | 0.823 | ||

| Behavioural intention | 1621 | 0.018/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | 0.126 (0.024 to 0.229) | 0.011 * | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.044 (−0.084 to 0.171) | 0.884 | ||

| Vegetables willing to try | 1621 | 0.015/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | 0.186 (0.033 to 0.338) | 0.013 * | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.018 (−0.171 to 0.207) | 1.000 | ||

| New vegetables consumed | 1612 | 0.032/0.000 | ||

| Baseline to Post-test | 1.589 (0.709 to 2.469) | <0.001 * | ||

| Baseline to Follow-up | 0.797 (−0.291 to 1.886) | 0.201 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poelman, A.A.M.; Cochet-Broch, M.; Wiggins, B.; McCrea, R.; Heffernan, J.E.; Beelen, J.; Cox, D.N. Effect of Experiential Vegetable Education Program on Mediating Factors of Vegetable Consumption in Australian Primary School Students: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082343

Poelman AAM, Cochet-Broch M, Wiggins B, McCrea R, Heffernan JE, Beelen J, Cox DN. Effect of Experiential Vegetable Education Program on Mediating Factors of Vegetable Consumption in Australian Primary School Students: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2020; 12(8):2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082343

Chicago/Turabian StylePoelman, Astrid A. M., Maeva Cochet-Broch, Bonnie Wiggins, Rod McCrea, Jessica E. Heffernan, Janne Beelen, and David N. Cox. 2020. "Effect of Experiential Vegetable Education Program on Mediating Factors of Vegetable Consumption in Australian Primary School Students: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial" Nutrients 12, no. 8: 2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082343

APA StylePoelman, A. A. M., Cochet-Broch, M., Wiggins, B., McCrea, R., Heffernan, J. E., Beelen, J., & Cox, D. N. (2020). Effect of Experiential Vegetable Education Program on Mediating Factors of Vegetable Consumption in Australian Primary School Students: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 12(8), 2343. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082343