Using the Internet: Nutrition Information-Seeking Behaviours of Lay People Enrolled in a Massive Online Nutrition Course

Abstract

1. Introduction

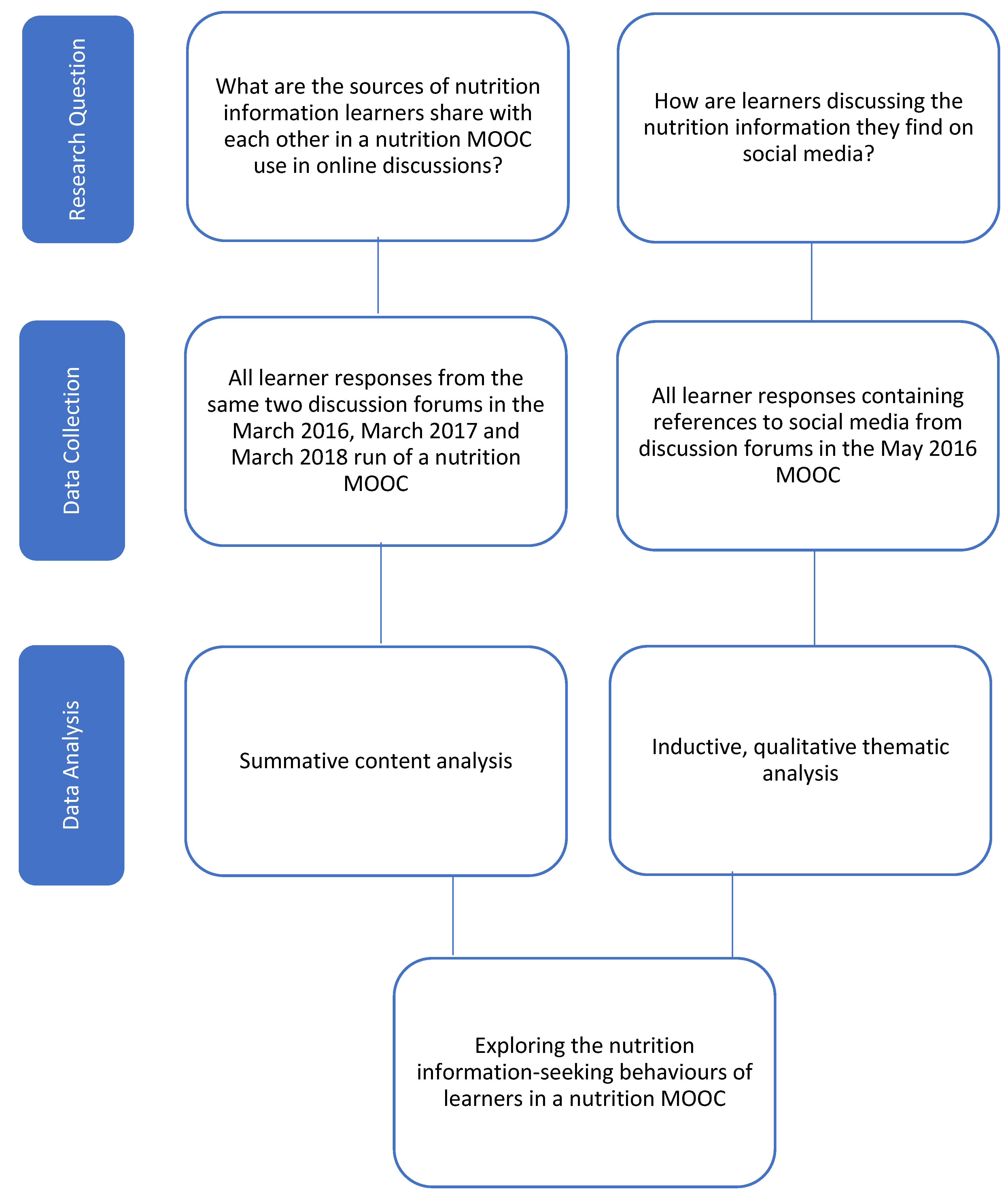

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Participants and Ethical Approval

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Categorising Sources of Nutrition Information—Content Analysis

2.3.2. Learners Communicating Nutrition Information Found Online—Framework Analysis

2.4. Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. Learners Backgrounds

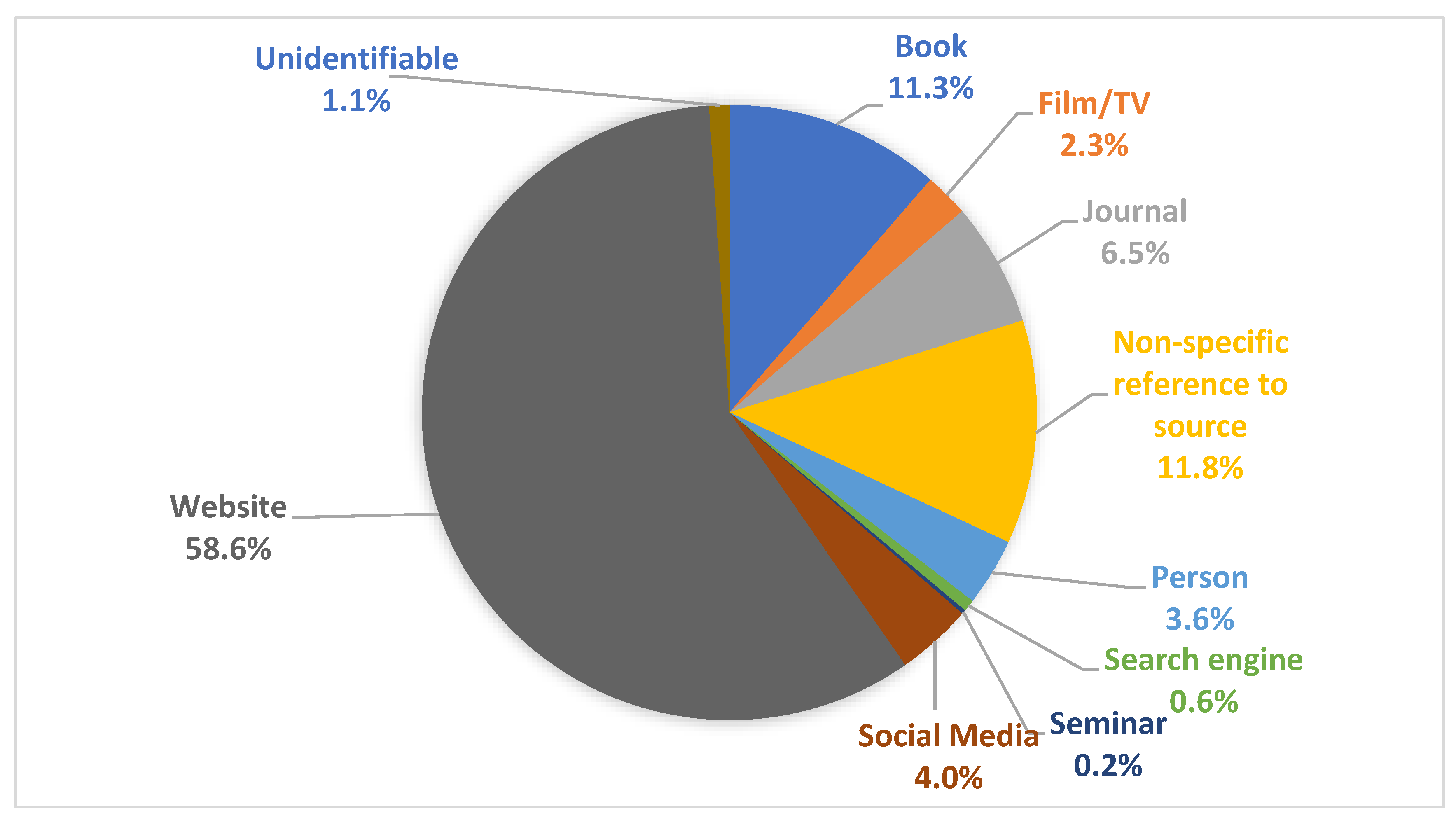

3.2. Where Did Learners Access Additional Nutrition Information?

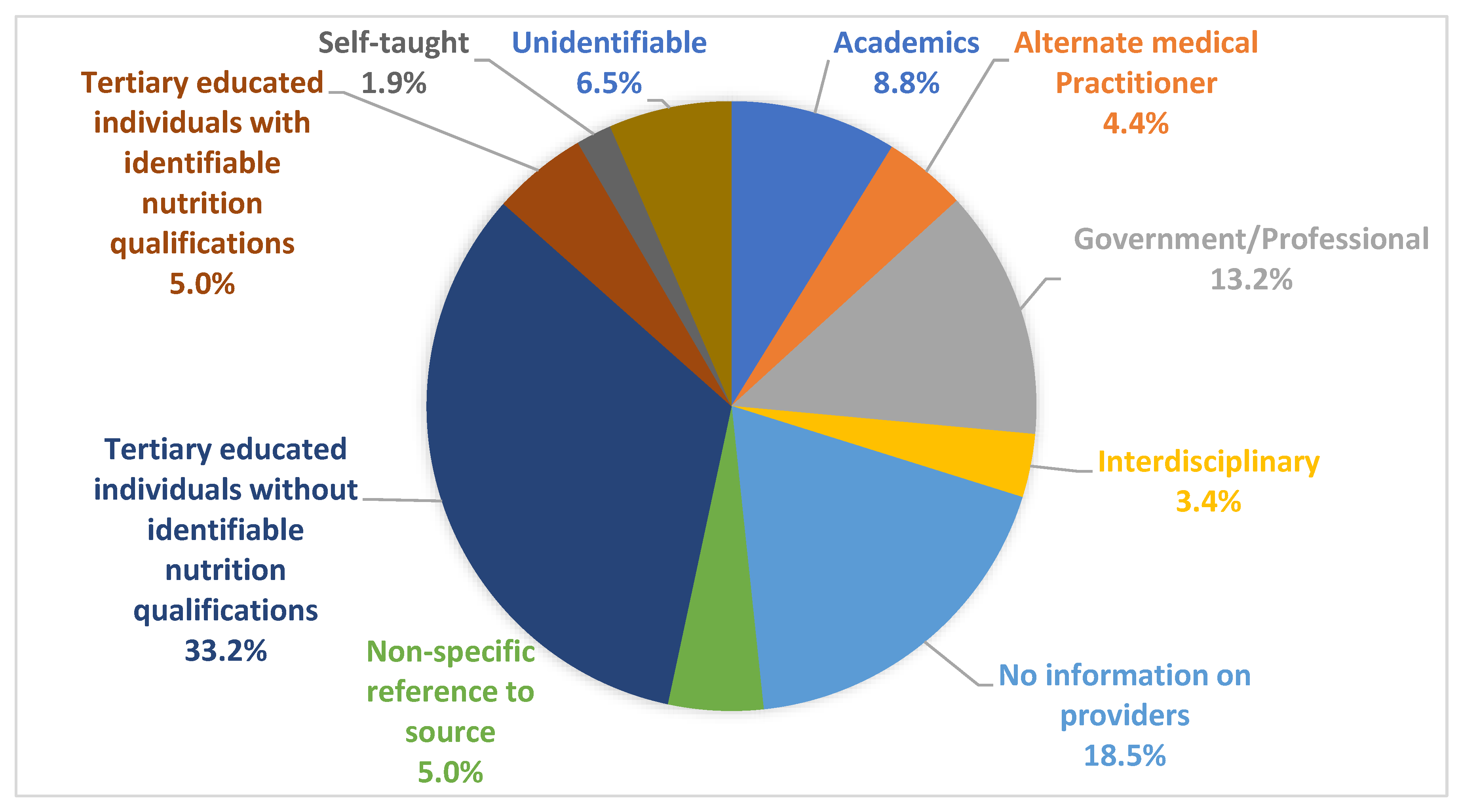

3.3. What were the Vocational Backgrounds of the Providers of the Nutrition Information Sources?

3.4. How are People Using Nutrition Information?

3.4.1. Learners as Teachers

3.4.2. Learners Sharing Information

3.4.3. Learners Using Social Media to Learn

3.4.4. Learners Perceptions of Social Media

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Source of Information | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Website | Information from a webpage, e.g., http://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2011/10/22/debunking-the-science-behind-lowering-cholesterol-levels.aspx | “Angel (SIC) Keys actually studied 22 countries and cherry picked the data to match his theory. http://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2011/10/22/debunking-the-science-behind-lowering-cholesterol-levels.aspx”—comment 139 |

| Book | Soft or hard copy books, e-books, e.g., Your Life in your Hands | “X, you might be interested to read a book written by Prof XXXXXXX called ’XXXXXXX”. She researched extensively to successfully (SIC) cure herself of terminal breast cancer and when she completely eliminated diary (SIC) from her diet, her tumors shrunk and disappeared. There is a lot to said of the idea that cows milk is great for baby cows. The human digestive system is not equipped to digest cows milk!”—comment 218 |

| Journal | Scientific studies published in an academic journal e.g., Journal of Applied Microbiology | “A 2013 systematic review found dairy is not inflammatory and may in fact have anti inflammatory properties http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/23446894/”—comment 217 |

| Social media | Blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc., e.g., https://www.facebook.com/ConversationUK/posts/728626687305674 | “https://www.facebook.com/ConversationUK/posts/728626687305674 Concerning the 10 portions per day, here is an article that claims that there are no marked benefits to health with increased consumption.”—comment 450 |

| Person | Referring to an individual | “Yes there are studies but too many confounding factors to turn association into causal. Most people who strive to eat lots of fruit and veg probably have overall healthy lifestyles which can’t easily be corrected for. As XXXXXXX claims a lot of these eating habits are markers rather than makers of health. The original 5 a day was invented as a slogan and just caught on.”—comment 451 |

| TV/Film | Television shows, films or documentaries, e.g., BBC programme ‘The science of staying young with XXXXXXX XXXXXXX’ | “Hi X I saw a BBC programme ‘The XXXXXXXXX with XXXXXXX they found out that if you eat purple foods that were rich in flaonoids, carotenoids, vitamin E and lycopene (basically blueberries:) red cabbage etc) it kept your body younger than your actual age.”—comment 112 |

| Search Engine | Reference to information listed on search engines, but no mention of a specific information source within the search engine, e.g., Google | “I think my diet is quite varied. Looking for new foods to buy this week, and assuming that it should be fresh and preferably not travelled too far, I found hardly anything new! The only new thing I bought was Jerusalem Artichokes, which I think were grown in the UK. Google tells me you can boil, sautee, roast or fry them so I’m going to try them boiled with carrots this evening. If they don’t taste nice boiled, I’m not going to add fat to them to make them more palatable! They were relatively expensive. Other foods I looked at had either been grown out of season or transported half way round the world. Most of them I have tried before (fresh pineapple, mango, watermelon), some I don’t like much (pomegranate, goji berries). I have seen a much larger variety of fresh vegetables on sale when I’ve visited London, but where I live is largely white British and so there is probably not much demand for these.”—comment 392 |

| Non-specific reference to source | Information that does not specify the ‘type’ of source, e.g., multiple research | “Dairy is acidic, multiple research has shown that consuming dairy causes osteoporosis. And communities that have the lowest intake of dairy e.g., Japan have also the lowest levels of osteoporosis. I’m really surprised to see advice to eat dairy in this course...”—comment 166 |

| Seminar | Reference to a seminar | “Sorry Catherine, you are wrong about saturated fat. It is NOT linked to diabetes or heart disease. There’s a Seminar with the principle researcher (A/Prof XXXXXXXX) from the CSIRO and the senior consultant endocrinologist (Prof XXXXX) from the Royal Adelaide Hospital talking about the value of lowering carbs and raising fats. Might be worth your while checking it out. There is also countless research on the value of saturated fat in the diet. The USDA has officially recognised that it is not dangerous as was thought. The low fat experiment has rewarded the west with record obesity and diabetes 2—not created by sat fat. I know a large number of athletes and non-athletes who are on a ketogenic diet and ticking all the boxes in relation to body fat, blood measures and general health. These people include up to 70% fat (sat and mono) in their diet. They are what is known as fat adapted which means they burn ketones rather that sugars. There are many books on this topic—for research try XXXXXXXXXX by DrsXXXXXXX and XXXXXX—XXXXXXXXXby XXXXXXXX is his story of dropping carbs to zero or close to it and raising fats”—comment 98 |

| Provider Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Tertiary educated individuals without identifiable nutrition qualifications | Tertiary education and training in an area where nutrition and dietetic science is not the main focus |

| -Medical | Holds a university degree in medicine |

| -Scientist | Holds a university degree in science |

| -Health care | Holds a university degree or professional training in health care and describes themselves as a health care professional |

| -Other | Holds a university degree or professional training in areas outside of science and health care such as chef, lawyer, journalist |

| Tertiary educated individuals with identifiable nutrition qualifications | Education and training in nutrition, e.g., Bachelor’s degree in nutrition and/or dietetics, Master’s degree or PhD in nutrition/dietetics from a university; Registered Nutritionist; Registered Dietitian; Accredited Practising Dietitian |

| Alternative Medicine Practitioner | Education and training in an alternate medicine/science area, e.g., naturopathy, kinesiology |

| Academic | Universities/authors peer reviewed papers |

| Government/Professional | Government department, international or national health organisations, professional health organisations |

| No information on providers | Unidentifiable provider of information, i.e., no information was identified on who authored/provided the information, or no information was found on the provider background in regards to education or training |

| Interdisciplinary | Multiple providers with different tertiary backgrounds |

| Interdisciplinary including nutrition professional | Multiple providers from different tertiary backgrounds, including a provider with tertiary nutrition education |

| Self-taught | Individuals who self-identified as having no formal tertiary education |

| Themes | Categories | Example Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Learners as teachers | Factual statements Providing advice Directive/authoritative/dialectical Opinion statements | “Yes, lactofermented vegetable have been around forever. Have a look at youtube for one of the best at this called – the art of fermentation by XXXX—good luck” (Learner 3ae09304) “I disagree that large doses of vitamin C are not particularly useful, Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) can be life saving (sic) when given in large amounts and research has proven that fact https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VrhkoFcOMI”(Learner 053170fe) “margarine is a great souce (sic) of trans fats—which are a great thing to avoid. Stick to the vegan lifestyle—its the gold standard for longevity and feeling well, just watch for B12 deficiency—you probably should be supplementing 1000mcg three times a week; its very cheap. Organic almond butter is a good (slightly expensive) alternative to spread to use on bread. You can make your own (everything is on YouTube.) (Learner 1caa6248) |

| Learners sharing information | Sign posting people to information Helpful/useful information Personal experiences/interests | “I got most of my information from a man called XXXXXX…I have found this on youtube it is in English however it does have Serbian subtitles but hopefully you can sit through it. It is titled ‘XXXXXX’”. (Learner 260b5b4c) “There are several websites and Facebook pages that deal with the subject of nutrition and health. XXXX Health on FB may interest you. Dr XXXX www.XXXXXX.com and XXXX XXXXXX www.XXXXXXXXX.com are online with many articles on nutrition, etc. These are just a sample.” (Learner: 899228a0) “I eat lots of brocolli I love it and believe it has lots of great nutrients. I did spot an article on FB the other day casting several healthy foods in a negative light if you ate too much of them and brocolli was one of them. Found it hard to believe lol!” (Learner: 028838da) |

| Learners using social media to learn | Description of acquiring nutrition information Inspired by information on social media Learners who want to inspire others | “For a cough I recently made a mixture of pineapple, lemon, ginger, cayenne and manuka honey after coming across it on Pinterest.” (Learner: d854374a) Where do you all seek to keep updated with the latest recommendations or ‘‘superfood’’ information and whole foods recipes and new food inspiration? I use Facebook—the XXX, XXX sometimes, the XXXX—mainly bloggers. I wouldn’t mind having some other resources. (Learner: 159b6c79) |

| Learners perceptions of social media | Effects of social media Usage of social media Opinions of social media | “Never been interested in using Twitter or Instagram…” (Learner: 65c13027) “With all the misinformation pedalled by unqualified celebrities and “insta-fit” social media types, it is more important than ever to lead a balanced and healthy lifestyle including a diet that is founded by evidenced based research.” (Learner: 7dcafc9c) |

| Course Run | Joiners 1 | Learners 2 | Number of Countries | Top 5 Countries | Age Range | % Age Range in MOOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Run 1 (May 2016) | 62,144 | 29,840 | 197 | Australia (41%), United Kingdom (22%), United States (7%), New Zealand (2%), and Canada (2%) | <18 years 18–25years 26–35 years 36–45 years 46–55 years 56–65 years >65 years Unknown | 0% 5% 14% 15% 18% 22% 22% 4% |

| Run 3 (March 2017) | 12,468 | 7696 | 171 | United Kingdom (31%), Australia (14%), United States (7%), Egypt (4%), and Canada (2%) | <18 years 18–25 years 26–35 years 36–45 years 46–55 years 56–65 years >65 years Unknown | 0% 11% 20% 15% 15% 17% 15% 5% |

| Run 6 (February 2018) | 6738 | 5106 | 156 | United Kingdom (31%), Australia (15%), United States (8%), Mexico (4%), and India (2%) | <18 years 18–25 years 26–35 years 36–45 years 46–55 years 56–65 years >65 years Unknown | 0% 8% 18% 15% 17% 17% 20% 4% |

| Source of Nutrition Information | Number (/476) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Book | 54 | 11.3% |

| Film/TV | 11 | 2.3% |

| Journal | 31 | 6.5% |

| Non-specific reference to source | 56 | 11.8% |

| Person | 17 | 3.6% |

| Search engine | 3 | 0.6% |

| Seminar | 1 | 0.2% |

| Social Media | 19 | 4% |

| Website | 279 | 58.6% |

| Unidentifiable (not in English, could not locate source, etc.) | 5 | 1.1% |

| Vocational Background of Provider | Number (/476) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Academics | 42 | 8.8% |

| Alternate medical practitioner | 21 | 4.4% |

| Government/Professional | 63 | 13.2% |

| Interdisciplinary | 16 | 3.4% |

| No information on providers | 88 | 18.5% |

| Non-specific reference to source | 24 | 5% |

| Tertiary educated individuals without identifiable nutrition qualifications | 158 | 33.2% |

| Doctors | 59 | 37.3% |

| Health care professionals, e.g., physiotherapist | 5 | 3.2% |

| Others, e.g., journalists, lawyers, chefs | 68 | 43% |

| Scientists | 26 | 16.5% |

| Tertiary educated individuals with identifiable nutrition qualifications | 24 | 5% |

| Self-taught | 9 | 1.9% |

| Unidentifiable (e.g., link broken, not in English, computer threat) | 31 | 6.5% |

References

- McMullan, M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: How this affects the patient–health professional relationship. Patient Educ. Couns. 2006, 63, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, D.; Kite, J.; Vassallo, A.J.; Chau, J.Y.; Partridge, S.; Freeman, B.; Gill, T. Food Trends and Popular Nutrition Advice Online–Implications for Public Health. Online J. Public Health Inform. 2018, 10, e213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannakoulias, N.; Tooby, R.; Sturrock, S. Celebrity over science? An analysis of Lyme disease video content on YouTube. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 191, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, S.A. Revisiting the online health information reliability debate in the wake of “web 2.0”: An inter-disciplinary literature and website review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2010, 79, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Reilly, T. What Is Web 2.0 2005. Available online: https://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html?page=1 (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- Toledano, C.A. Web 2.0: The Origin of the Word That Has Changed the Way We Understand Public Relations; Barcelona International PR Conference: Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Daugherty, T.; Eastin, M.S.; Bright, L. Exploring consumer motivations for creating user-generated content. J. Interact. Advert. 2008, 8, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEW Research Centre. News Use across Social Media Platforms. 2017. Available online: https://www.journalism.org/2017/09/07/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-2017/ (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- PEW Research Centre. The Social Life of Health Information 2011. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2011/05/12/the-social-life-of-health-information-2011/ (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Pollard, C.M.; Pulker, C.E.; Meng, X.; Kerr, D.A.; Scott, J.A. Who uses the internet as a source of nutrition and dietary information? An Australian population perspective. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PEW Research Centre. Science News and Information Today 2017. Available online: https://www.journalism.org/2017/09/20/science-news-and-information-today/ (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Rowe, S.B.; Alexander, N. Communicating Health and Nutrition Information After the Death of Expertise. Nutr. Today 2017, 52, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.; Wyness, L. ‘Don’t tell me what to eat!’–W ays to engage the population in positive behaviour change. Nutr. Bull. 2013, 38, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declercq, J.; Tulkens, S.; Van Leuven, S. The produsing expert consumer: Co-constructing, resisting and accepting health-related claims on social media in response to an infotainment show about food. Health 2018, 26, 602–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassier, P.; Srour, B.; Raynard, B.; Zelek, L.; Cohen, P.; Bachmann, P.; Cottet, V. Fasting and weight-loss restrictive diet practices among 2,700 cancer survivors: Results from the NutriNet-Santé cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 2687–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S.J.; Tan, C. Biological, psychological and social processes that explain celebrities’ influence on patients’ health-related behaviors. Arch Public Health 2015, 73, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caulfield, T. From Kim Kardashian to Dr. Oz: The future relevance of popular culture to our health and health policy. Ottawa L. Rev. 2016, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, M. Margaret McCartney: Swapping systematic reviews for celebrity endorsements. BMJ 2017, 356, j228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Myrick, J.; Erlichman, S. How Audience Involvement and Social Norms Foster Vulnerability to Celebrity-Based Dietary Misinformation. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, A.; Chamberlain, K. The problematic messages of nutritional discourse: A case-based critical media analysis. Appetite 2017, 108, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitchens, B.; Harle, C.A.; Li, S. Quality of health-related online search results. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 57, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.J.; Atkin, D. User generated content and credibility evaluation of online health information: A meta analytic study. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future Learn. Available online: www.futurelearn.com (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Zawacki-Richter, O.; Bozkurt, A.; Alturki, U.; Aldraiweesh, A. What research says about MOOCs–An explorative content analysis. IRRODL 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.; Malcolm, B.; Ramagopalan, S.; Syrad, H. Real-world data and the patient perspective: The PROmise of social media? BMC Med. 2019, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.; Adamski, M.; Blumfield, M.; Dart, J.; Murgia, C.; Volders, E.; Truby, H. Promoting Evidence Based Nutrition Education Across the World in a Competitive Space: Delivering a Massive Open Online Course. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Australian Dietary Guidelines. 2013. Available online: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/guidelines (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Class Central’s Top 100 MOOCs of All Time (2019 Edition). Available online: https://www.classcentral.com/report/top-moocs-2019-edition/ (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Goldberg, L.R.; Crocombe, L.A. Advances in medical education and practice: Role of massive open online courses. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2017, 8, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Firth, J. Qualitative data analysis: The framework approach. Nurs. Res. 2011, 18, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prestin, A.; Vieux, S.N.; Chou, W.-Y.S. Is online health activity alive and well or flatlining? Findings from 10 years of the Health Information National Trends Survey. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20, 790–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szwajcer, E.M.; Hiddink, G.J.; Maas, L.; Koelen, M.A.; Van Woerkum, C.M. Nutrition-related information-seeking behaviours of women trying to conceive and pregnant women: Evidence for the life course perspective. Fam. Pract. 2008, 25 (Suppl. 1), i99–i104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cash, T.; Desbrow, B.; Leveritt, M.; Ball, L. Utilization and preference of nutrition information sources in Australia. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2288–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, L. Viral misinformation threatens public health. Can. Med. Assoc. 2017, 189, E1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macris, P.C.; Schilling, K.; Palko, R. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Revised 2017 standards of practice and standards of professional performance for registered dietitian nutritionists (competent, proficient, and expert) in oncology nutrition. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 736–748; e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.; Ross, T.; Castor, C. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Revised 2017 standards of practice and standards of professional performance for registered dietitian nutritionists (competent, proficient, and expert) in diabetes care. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 932–946; e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. What Is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist 2019. Available online: https://www.eatrightpro.org/about-us/what-is-an-rdn-and-dtr/what-is-a-registered-dietitian-nutritionist (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Dietitians Association of Australia. Dietitian or Nutritionist? 2019. Available online: https://daa.asn.au/what-dietitans-do/dietitian-or-nutritionist/ (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Dietitians Association of Australia. New Survey: Dietitians Trump Internet and Celebrities for Advice. Available online: https://daa.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Media-Release-Dietitians-trump-internet-and-celebrities-for-nutriton-advice-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2019).

- Shahar, S.; Shirley, N.; Noah, S.A. Quality and accuracy assessment of nutrition information on the Web for cancer prevention. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2013, 38, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, T.; Fahy, D. Science, celebrities, and public engagement. Issues Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Goldie, J.G.S. Connectivism: A knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helm, J.; Jones, R.M. Practice paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Social media and the dietetics practitioner: Opportunities, challenges, and best practices. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1825–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayres, E.J. The impact of social media on business and ethical practices in dietetics. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1539–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowan, S.; Sood, S.; Truby, H.; Dordevic, A.; Adamski, M.; Gibson, S. Inflaming Public Interest: A Qualitative Study of Adult Learners’ Perceptions on Nutrition and Inflammation. Nutrients 2020, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, L.M.; Moriartey, S.; Stadnyk, J.; Basualdo-Hammond, C. Assessment of Registered Dietitians’ beliefs and practices for a nutrition counselling approach. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2016, 77, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, E. Why are scientists so quite? Cultural and philosophical constraints on the public voice of the scientist. J. Proc. R. Soc. New South Wales 2018, 151, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Probst, Y.C.; Peng, Q. Social media in dietetics: Insights into use and user networks. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 76, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.D.; Cohen, N.L.; Fulgoni, V.L.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Wellman, N.S. From nutrition scientist to nutrition communicator: Why you should take the leap. AJCN 2006, 83, 1272–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel, L.A.; Mattson, M.E. Reading is believing: The truth effect and source credibility. Conscious Cogn. 2011, 20, 1705–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, L.K.; Brashier, N.M.; Payne, B.K.; Marsh, E.J. Knowledge does not protect against illusory truth. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R. Containing health myths in the age of viral misinformation. Can Med. Assoc. 2018, 190, E578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, J.; Ball, L.; Hiddink, G.J. Nutrition in medical education: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e379–e389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamski, M.; Gibson, S.; Leech, M.; Truby, H. Are doctors nutritionists? What is the role of doctors in providing nutrition advice? Nutr. Bull. 2018, 43, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poínhos, R.; Oliveira, B.M.; Van Der Lans, I.A.; Fischer, A.R.; Berezowska, A.; Rankin, A.; De Almeida, M.D. Providing Personalised Nutrition: Consumers’ Trust and Preferences Regarding Sources of Information, Service Providers and Regulators, and Communication Channels. Public Health Genom. 2017, 20, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamski, M.; Truby, H.; M. Klassen, K.; Cowan, S.; Gibson, S. Using the Internet: Nutrition Information-Seeking Behaviours of Lay People Enrolled in a Massive Online Nutrition Course. Nutrients 2020, 12, 750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030750

Adamski M, Truby H, M. Klassen K, Cowan S, Gibson S. Using the Internet: Nutrition Information-Seeking Behaviours of Lay People Enrolled in a Massive Online Nutrition Course. Nutrients. 2020; 12(3):750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030750

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamski, Melissa, Helen Truby, Karen M. Klassen, Stephanie Cowan, and Simone Gibson. 2020. "Using the Internet: Nutrition Information-Seeking Behaviours of Lay People Enrolled in a Massive Online Nutrition Course" Nutrients 12, no. 3: 750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030750

APA StyleAdamski, M., Truby, H., M. Klassen, K., Cowan, S., & Gibson, S. (2020). Using the Internet: Nutrition Information-Seeking Behaviours of Lay People Enrolled in a Massive Online Nutrition Course. Nutrients, 12(3), 750. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030750