Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television among Canadian Adolescents, 2011 to 2016

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis

2.2. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Food and Beverage Advertisements Aired on Television

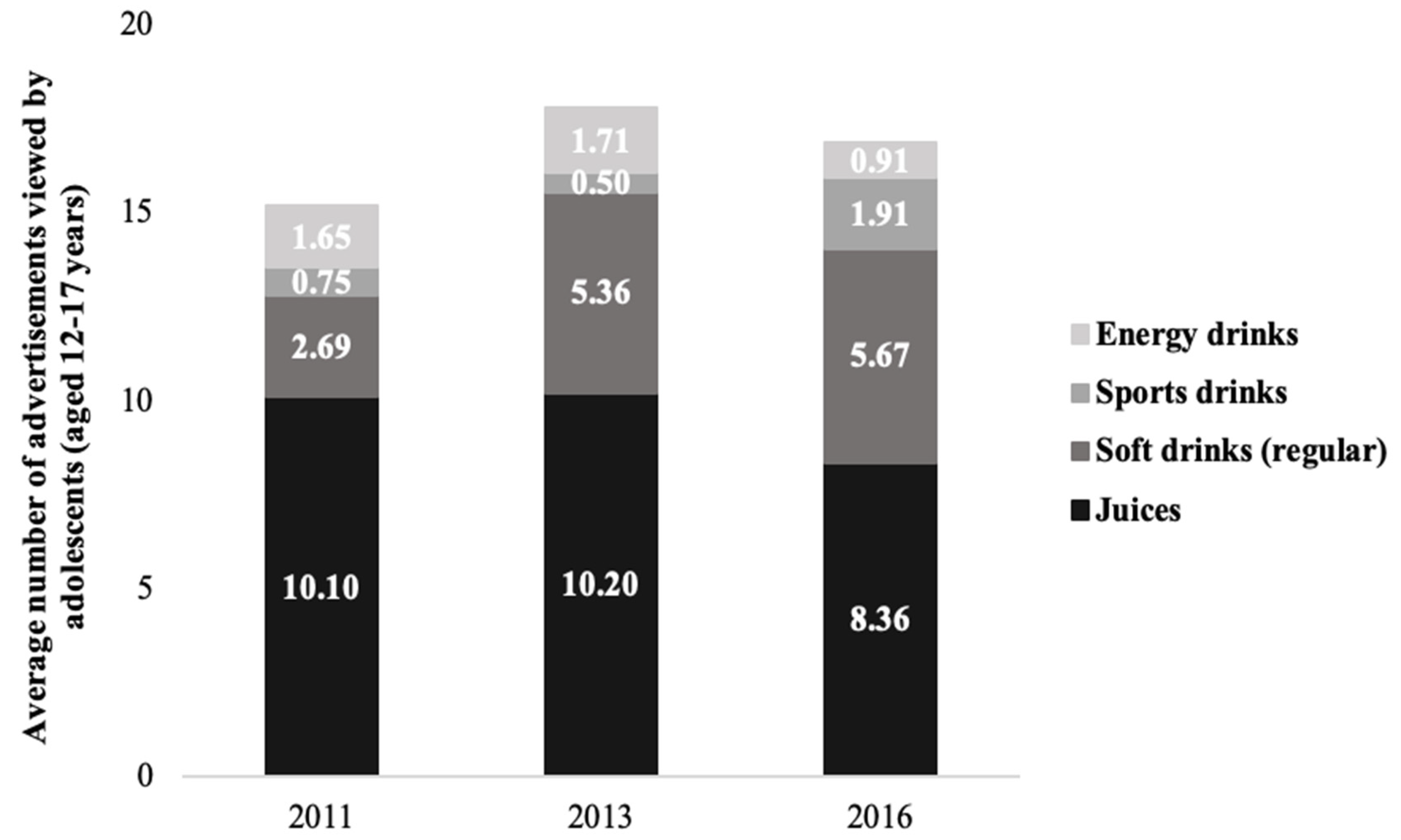

3.2. Adolescents’ Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television

3.3. Beverages with Free Sugars

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGinnis, J.M.; Gootman, J.; Kraak, V.I. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings, G.; McDermott, L.; Angus, K.; Stead, M.; Thomson, S. The Extent, Nature and Effects of Food Promotion to Children: A Review of the Evidence; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, G.; Angus, K.; Hastings, G.; Caraher, M. Systematic reviews of the evidence on the nature, extent and effects of food marketing to children. A retrospective summary. Appetite 2013, 62, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghirad, B.; Duhaney, T.; Motaghipisheh, S.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Johnston, B.C. Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children’s dietary intake and preference: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, J.; Kelly, B.; Boyland, E.; McMahon, A.T. The impact of marketing and advertising on food behaviours: Evaluating the evidence for a causal relationship. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Kelly, H.; Yeatman, H.; Boyland, E. Food marketing influences children’s attitudes, preferences and consumption: A systematic critical review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, M.; Wakefield, M.; Niven, P.; Chapman, K.; Crawford, D.; Pratt, I.S.; Baur, L.A.; Flood, V.; Morley, B. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents’ food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite 2012, 58, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.M.; Szczypka, G.; Chaloupka, F.J. Adolescent exposure to food advertising on television. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, S251–S256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.L.; Sarda, V.; Schwartz, M.B.; Brownell, K.D. Redefining “child-directed advertising” to reduce unhealthy television food advertising. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada; The Canadian Institute for Health Information. Obesity in Canada. 2011. Available online: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/Obesity_in_canada_2011_en.pdf. (accessed on 9 November 2018).

- Rodd, C.; Sharma, A.K. Recent trends in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Canadian children. CMAJ 2016, 188, E313–E320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0795-01 Measured Children and Youth Body Mass Index (BMI) (World Health Organization Classification), by Age Group and Sex, Canada and Provinces, Canadian Community Health Survey-Nutrition. 2019. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310079501&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.3&pickMembers%5B2%5D=3.1&pickMembers%5B3%5D=5.5 (accessed on 9 November 2018).

- Garriguet, D. Canadians’ eating habits. Health Rep. 2007, 18, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Garriguet, D. Sodium consumption at all ages. Health Rep. 2007, 18, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois, K.; Garriguet, D. Sugar consumption among Canadians of all ages. Health Rep. 2011, 22, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moubarac, J.C. Ultra-Processed Foods in Canada: Consumption, Impact on Diet Quality and Policy Implications; University of Montreal: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2017; Available online: https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/media-centre/hs-report-upp-moubarac-dec-5-2017.ashx (accessed on 6 November 2018).

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugars Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/149782/9789241549028_eng.pdf;jsessionid=DB27D7FF33CEE9A8E0A544505A81CC41?sequence=1 (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Garriguet, D. Beverage consumption of children and teens. Health Rep. 2008, 19, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Story, M.; French, S. Food advertising and marketing directed at children and adolescents in the US. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2004, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC). Communications Monitoring Report; CRTC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. Available online: https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/policymonitoring/2017/index.htm (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Federal Trade Commission. A Review of Food Marketing to Children and Adolescents: Follow-Up Report. 2012. Available online: https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/review-food-marketing-children-and-adolescents-follow-report/121221foodmarketingreport.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Powell, L.M.; Harris, J.L.; Fox, T. Food marketing expenditures aimed at youth: Putting the numbers in context. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luxton, S.; Reid, M.; Mavondo, F. Integrated marketing communication capability and brand performance. J. Advert. 2015, 44, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Evaluating Implementation of the WHO Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children. Progress, Challenges and Guidance for Next Steps in WHO European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/384015/food-marketing-kids-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 14 October 2019).

- Office de la Protection du Consommateur. Advertising Directed at Children under 13 Years of Age. Guide to Application of Sections 248 and 249 Consumer Protection Act; Office de la Protection du Consommateur: Québec, QC, Canada, 2012. Available online: https://www.opc.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/media/documents/consommateur/sujet/publicite-pratique-illegale/EN_Guide_publicite_moins_de_13_ans_vf.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2019).

- Ad Standards. The Canadian Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative: 2018 Compliance Report; Ad Standards: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://adstandards.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/AdStandards-CAI-Compliance-Report-18-EN.pdf (accessed on 29 January 2019).

- Parliament of Canada. Bill S-228—An Act to Amend the Food and Drugs Act (Prohibiting Food and Beverage Marketing Directed at Children). 2017. Available online: https://www.parl.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/bill/S-228/third-reading (accessed on 25 September 2018).

- Duggan, K. Liberals Plan to Amend Junk Food Ad Bill: Petitpas Taylor. iPolitics, 12 December 2017. Available online: https://ipolitics.ca/2017/12/12/liberals-plan-amend-junk-food-ad-bill-petitpas-taylor/ (accessed on 16 October 2019).

- Potvin Kent, M.; Pauzé, E.; Roy, E.-A.; De Billy, N.; Czoli, C. Children and adolescents’ exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penchmann, C.; Levine, L.; Loughlin, S.; Leslie, F.M. Impulsive and self-conscious: Adolescents’ vulnerability to advertising and promotion. J. Public Policy Mark. 2005, 24, 202–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, F.M.; Levine, L.J.; Loughlin, S.E.; Penchmann, C. Adolescents Psychological & Neurobiological Development: Implications for Digital Marketing; Centre for Digital Democracy and Berkeley Media Studies Group: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: http://digitalads.org/sites/default/files/publications/digitalads_leslie_et_al_nplan_bmsg_memo.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Luger, M.; Lafontan, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Winzer, E.; Yumuk, V.; Farpour-Lambert, N. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review from 2013 to 2015 and a comparison with previous studies. Obes. Facts. 2017, 10, 674–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Pan, A.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; SeeHoe, N.; Adams, J.; Allemandi, L.; Bahena-Espina, L.; Barquera, A. Global benchmarking of children’s exposure to television advertising of unhealthy food and beverages across 22 countries. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potvin Kent, M.; Smith, J.R.; Pauzé, E.; L’Abbé, M. The effectiveness of the food and beverage industry’s self-established Uniform Nutrition Criteria at improving the healthfulness of food advertising viewed by Canadian children on television. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potvin Kent, M.; Martin, C.; Kent, E.A. Changes in the volume, power and nutritional quality of foods marketed to children on television in Canada 2006-2011. Obesity 2014, 22, 2053–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numeris. A Guide to Numeris’ Meter Panel. 2018. Available online: http://en.numeris.ca/participants/meter-panel (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Powell, L.M.; Szczypka, G.; Chaloupka, F.J. Trends in exposure to television food advertisements among children and adolescents in the United States. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010, 164, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming-Milici, F.; Harris, J.L. Television food advertising viewed by preschoolers, children and adolescents: Contributors to differences in exposure for black and white youth in the United States. Pediatr. Obes. 2018, 13, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.C.; Veerman, J.L.; Hammond, D. The Health and Economic Impact of a Tax on Sugary Drinks in Canada (Summary). 2017. Available online: https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/canada/media-centre/the-health-and-economic-impact-of-a-sugary-drink-tax-in-canada-summary.ashx?la=en&hash=69765598FF624EE7D8586EBAD7BCF96835F3FA10 (accessed on 14 October 2019).

- Potvin Kent, M.; Wanless, A. The influence of the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative: Change in children’s exposure to food advertising on television in Canada between 2006–2009. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, W.C.; Harris, J.L. Trends in Television Food Advertising to Young People: 2017 Update; Rudd Centre for Food Policy and Obesity: University of Connecticut, Hartford, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/RuddReport_TVFoodAdvertising_6_14.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2018).

- King, L.; Hebden, L.; Grunseit, A.; Kelly, B.; Chapman, K.; Venugopal, K. Industry self-regulation of television food advertising: Responsible or responsive? Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, e390–e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Social Care: Global Public Health Directorate: Obesity, Food and Nutrition. Childhood Obesity: A Plan for Action (Chapter 2); Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/718903/childhood-obesity-a-plan-for-action-chapter-2.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Ross, C.S.; De Bruijn, A.; Jernigan, D. Do time restrictions on alcohol advertising reduce youth exposure? J. Public Aff. 2013, 13, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization’s Regional Office for Europe. Tackling Food Marketing to Children in a Digital World: Trans-Disciplinary Perspectives; WHO Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016; Available online: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/322226/Tackling-food-marketing-children-digital-world-trans-disciplinary-perspectives-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Elsey, J.W.B.; Harris, J.L. Trends in food and beverage television brand appearances viewed by children and adolescents from 2009 to 2014 in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 1928–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherriff, J.; Griffiths, D.; Daube, M. Cricket: Notching up runs for food and alcohol companies? Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2010, 34, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalition Poids. Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Marketing Unveiled; Coalition Poids: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2012; Available online: http://cqpp.qc.ca/app/uploads/2018/08/Report_Marketing-Sugar-Sweetened-Beverage_Volume2-Price_2012-03_petit.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

| Food/Beverage Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cakes | All cakes and puddings, including items that are ready to eat or require additional preparation (excludes frozen pastry and pie shells) |

| Candy | Confectionary made from sugar, water, flavoring and food coloring (excludes candy with chocolate) |

| Cereal | Ready-to-eat products marketed as breakfast food (excludes infant cereals and oatmeal) |

| Cheese | Cheese products in various formats, e.g., brick, string or slice (excludes cottage cheese) |

| Chocolate | Individually wrapped chocolate and candy bars (excludes boxed chocolate and candy with chocolate) |

| Compartment snacks | Pre-packaged products comprise of two or more ingredients in separate compartments sold as portable snacks or meals |

| Cookies | Small baked sweet biscuits |

| Ice cream | Includes ice cream, frozen yogurt, sherbet, sorbet and frozen treats made from these foods |

| Pizza | Pizza not sold in restaurants |

| Portable snacks | Cereal, protein or fruit bars and squares, and fruit snacks |

| Snack foods | Savory snacks such as chips, pretzels, cheese puffs, and meat-based snacks like jerky (excludes crackers) |

| Fast food restaurants | Foods sold at restaurants where ordering is conducted at a counter or drive-through, where menu boards are placed above the counter, and the table is cleaned up by the customer |

| Restaurants | Restaurants that serve prepared food and beverages that are ordered from a menu once seated and are consumed on the premises |

| Yogurt | Yogurt in tub, tube, and drink form (excludes frozen yogurt) |

| Juices, drinks and nectars | Sweetened and unsweetened juices and beverages that come in liquid, frozen, concentrated, and powdered forms (excludes water, milk and alternatives, tea and coffee drinks, cocktail mixers, and alcoholic beverages) |

| Energy drinks | Drink products that are primarily consumed for the purpose of boosting one’s mental and physical stimulation |

| Soft drinks (regular) | Any non-alcoholic carbonated drink |

| Soft drinks (diet) | Diet versions of soft drinks |

| Sports drinks | Drink products that are primarily consumed to rehydrate the body and replace electrolytes lost during physical activity |

| Food/Beverage Category | Total Advertisements Aired | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2011 n (%) | May 2013 n (%) | May 2016 n (%) | % Change in Ad Frequency May 2011 to 2016 | |

| Cakes | 52 (0.1) | 3 (<0.1) | 423 (0.5) | +713% |

| Candy | 814 (1.0) | 4893 (5.9) | 3623 (4.1) | +345% |

| Cereal | 7349 (8.7) | 3044 (3.7) | 2992 (3.4) | −59% |

| Cheese | 5931 (7.0) | 3731 (4.5) | 4924 (5.6) | −17% |

| Chocolate | 10,001 (11.8) | 12,165 (14.8) | 7140 (8.1) | −29% |

| Compartment snacks | - | 352 (0.4) | 1 (<0.1) | - |

| Cookies | 3875 (4.6) | 2333 (2.8) | 1597 (1.8) | −59% |

| Ice cream | 1318 (1.6) | 2387 (2.9) | 2626 (3.0) | +99% |

| Pizza | 2332 (2.8) | 1258 (1.5) | 1498 (1.7) | −36% |

| Portable snacks | 2397 (2.8) | 1892 (2.3) | 1739 (2.0) | −27% |

| Snack foods | 2158 (2.5) | 4850 (5.9) | 5609 (6.4) | +160% |

| Fast food | 28,508 (33.7) | 26,861 (32.6) | 35,652 (40.6) | +25% |

| Restaurants | 5686 (6.7) | 4506 (5.5) | 5918 (6.7) | +4% |

| Yogurt | 7660 (9.0) | 4777 (5.8) | 2810 (3.2) | −63% |

| Juices | 3491 (4.1) | 4615 (5.6) | 4845 (5.5) | +39% |

| Energy drinks | 765 (0.9) | 804 (1.0) | 857 (1.0) | +12% |

| Soft drinks (regular) | 1199 (1.4) | 3878 (4.7) | 4247 (4.8) | +254% |

| Soft drinks (diet) | 804 (0.9) | - | 318 (0.4) | −60% |

| Sports drinks | 360 (0.4) | 83 (0.1) | 1006 (1.1) | +179% |

| TOTAL | 84,700 (100) | 82,432 (100) | 87,825 (100) | +4% |

| Food/Beverage Category | Average Number of Advertisements Viewed by Adolescents (Aged 12–17 Years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2011 n (%) | May 2013 n (%) | May 2016 n (%) | % Change in Ad Exposure (n) May 2011 to 2016 | |

| Cakes | 0.15 (<0.1) | - | 0.66 (0.4) | +340% |

| Candy | 3.40 (1.5) | 9.62 (5.3) | 9.96 (6.5) | +193% |

| Cereal | 22.70 (10.3) | 8.24 (4.6) | 10.21 (6.6) | −55% |

| Cheese | 17.18 (7.8) | 10.24 (5.7) | 10.58 (6.9) | −38% |

| Chocolate | 22.55 (10.2) | 21.54 (11.9) | 7.62 (5.0) | −66% |

| Compartment snacks | - | 0.67 (0.4) | - | - |

| Cookies | 10.09 (4.6) | 5.19 (2.9) | 2.60 (1.7) | −74% |

| Ice cream | 2.88 (1.3) | 3.93 (2.2) | 3.94 (2.6) | +37% |

| Pizza | 6.24 (2.8) | 2.76 (1.5) | 1.31 (0.9) | −79% |

| Portable snacks | 9.35 (4.2) | 4.11 (2.3) | 5.14 (3.3) | −45% |

| Snack foods | 3.40 (1.5) | 7.53 (4.2) | 6.67 (4.3) | +96% |

| Fast food | 74.76 (33.8) | 68.00 (37.7) | 64.05 (41.7) | −14% |

| Restaurants | 12.50 (5.7) | 10.83 (6.0) | 8.14 (5.3) | −35% |

| Yogurt | 19.19 (8.7) | 10.31 (5.7) | 5.06 (3.3) | −74% |

| Juices | 10.10 (4.6) | 10.20 (5.7) | 8.36 (5.4) | −17% |

| Energy drinks | 1.65 (0.8) | 1.71 (0.9) | 0.91 (0.6) | −45% |

| Soft drinks (regular) | 2.69 (1.2) | 5.36 (3.0) | 5.67 (3.7) | +111% |

| Soft drinks (diet) | 1.68 (0.8) | - | 0.83 (0.5) | −51% |

| Sports drinks | 0.75 (0.3) | 0.25 (0.1) | 1.91 (1.2) | +155% |

| TOTAL | 221.26 (100) | 180.49 (100) | 153.62 (100) | −31% |

| Food/Beverage Category | Average Number of Advertisements Viewed by Adolescents (Aged 12–17 Years) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children’s Specialty Stations (n = 2) | Teen Specialty Stations (n = 2) | Generalist Stations (n = 27) | ||||||||||

| May 2011 | May 2013 | May 2016 | % Change May 2011 to 2016 | May 2011 | May 2013 | May 2016 | % Change May 2011 to 2016 | May 2011 | May 2013 | May 2016 | % Change May 2011 to 2016 | |

| Cakes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.15 | - | 0.66 | 340% |

| Candy | 2.04 | 4.35 | 7.89 | +287% | 0.29 | 0.45 | 1.67 | 476% | 1.08 | 4.82 | 2.07 | 92% |

| Cereal | 7.32 | 2.81 | 7.23 | −1% | - | - | - | - | 15.38 | 5.43 | 2.99 | −81% |

| Cheese | 4.74 | 2.76 | 4.06 | -14% | 0.36 | - | - | - | 12.08 | 7.47 | 6.52 | −46% |

| Chocolate | 0.87 | 1.72 | 1.60 | +84% | 1.01 | 0.33 | 0.14 | −86% | 20.66 | 19.49 | 5.87 | −72% |

| Compartment snacks | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.67 | - | |

| Cookies | 1.71 | 0.55 | 0.17 | −90% | 0.82 | 0.25 | - | - | 7.56 | 4.39 | 2.43 | −68% |

| Ice cream | 0.43 | 1.56 | 0.63 | +47% | - | - | - | - | 2.45 | 2.36 | 3.31 | 35% |

| Pizza | 0.23 | - | 0.39 | +70% | - | - | - | - | 6.01 | 2.76 | 0.92 | −85% |

| Portable snacks | 4.01 | 1.19 | 2.83 | −29% | - | - | - | - | 5.35 | 2.92 | 2.31 | −57% |

| Snack foods | 0.12 | - | 0.48 | +300% | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.16 | −41% | 3.01 | 7.18 | 6.03 | 100% |

| Fast food | 11.64 | 8.51 | 8.36 | −28% | 2.23 | 0.83 | 0.91 | −59% | 60.88 | 58.67 | 54.77 | −10% |

| Restaurants | 0.91 | 1.15 | 0.11 | −88% | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.08 | −38% | 11.47 | 9.43 | 7.95 | −31% |

| Yogurt | 4.39 | 1.56 | 1.94 | −56% | 0.44 | 0.78 | 0.03 | −93% | 14.36 | 7.97 | 3.10 | −78% |

| Juices | 1.29 | 0.55 | 1.15 | −11% | 0.29 | 0.57 | - | - | 8.52 | 9.09 | 7.21 | −15% |

| Energy drinks | - | 0.18 | 0.06 | ∞ | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.07 | −72% | 1.40 | 1.22 | 0.79 | −44% |

| Soft drinks (regular) | 0.39 | 0.70 | 0.51 | +31% | 0.60 | 1.24 | 0.26 | −57% | 1.71 | 3.41 | 4.89 | 186% |

| Soft drinks (diet) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.68 | - | 0.83 | −51% |

| Sports drinks | - | - | - | - | 0.26 | - | 0.01 | −96% | 0.49 | 0.25 | 1.89 | 286% |

| TOTAL | 40.09 | 27.58 | 37.41 | −7% | 6.94 | 5.36 | 1.67 | −76% | 174.24 | 147.54 | 114.54 | −34% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Czoli, C.D.; Pauzé, E.; Potvin Kent, M. Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television among Canadian Adolescents, 2011 to 2016. Nutrients 2020, 12, 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020428

Czoli CD, Pauzé E, Potvin Kent M. Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television among Canadian Adolescents, 2011 to 2016. Nutrients. 2020; 12(2):428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020428

Chicago/Turabian StyleCzoli, Christine D, Elise Pauzé, and Monique Potvin Kent. 2020. "Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television among Canadian Adolescents, 2011 to 2016" Nutrients 12, no. 2: 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020428

APA StyleCzoli, C. D., Pauzé, E., & Potvin Kent, M. (2020). Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television among Canadian Adolescents, 2011 to 2016. Nutrients, 12(2), 428. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020428