Vitamin D Supplementation Associated to Better Survival in Hospitalized Frail Elderly COVID-19 Patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Intervention: Vitamin D Supplementation

2.3. Primary Outcome: 14-Day COVID-19 Mortality

2.4. Secondary Outcome: Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement (OSCI) Score for COVID-19 in Acute Phase

2.5. Covariables

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethics

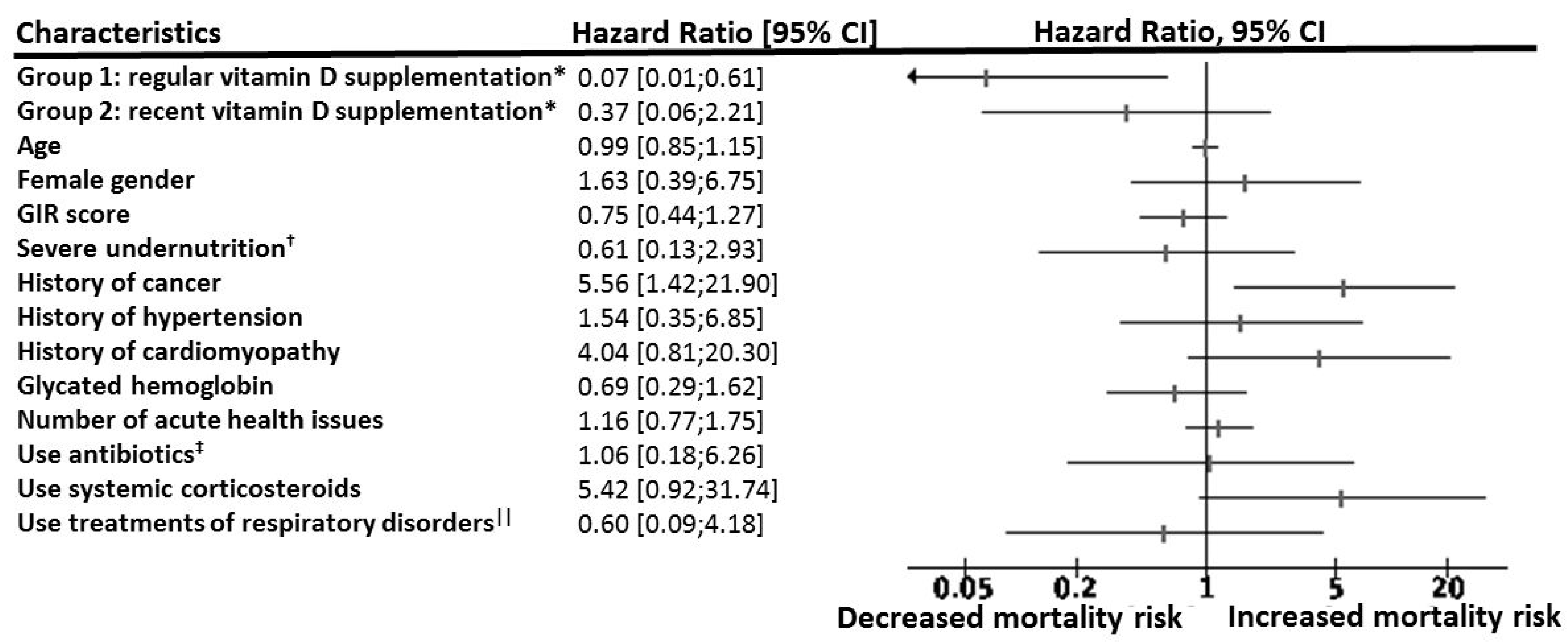

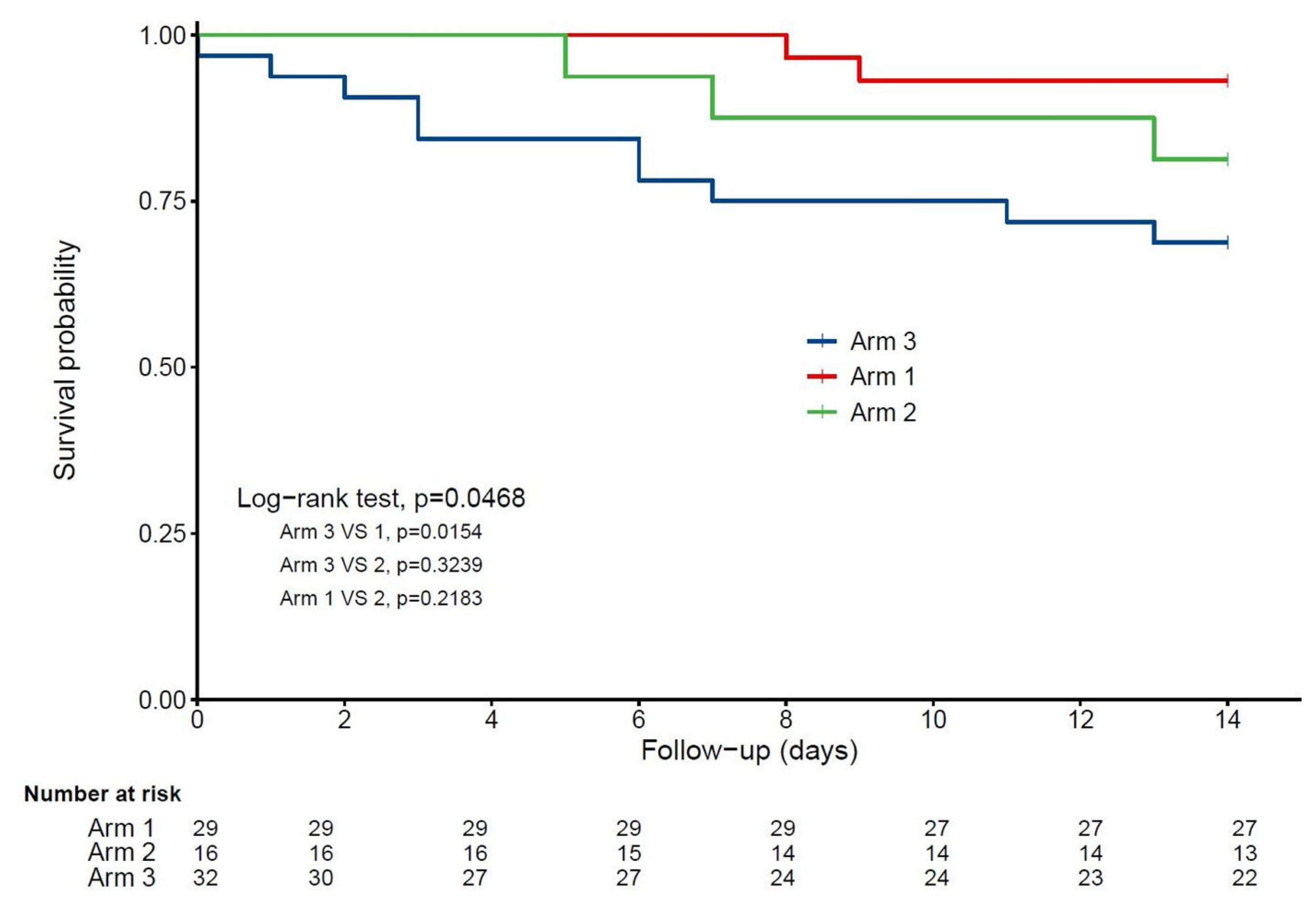

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, D.-G.; Shin, H.-J.; Kim, M.-H.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Myoung, J.; Kim, B.-T.; Kim, S.-J. Current Status of Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Therapeutics, and Vaccines for Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 30, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glinsky, G.V. Tripartite Combination of Candidate Pandemic Mitigation Agents: Vitamin D, Quercetin, and Estradiol Manifest Properties of Medicinal Agents for Targeted Mitigation of the COVID-19 Pandemic Defined by Genomics-Guided Tracing of SARS-CoV-2 Targets in Human Cells. Biomed. 2020, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benhamou, C.-L.; Souberbielle, J.-C.; Cortret, B.; Fardellone, P.; Gauvain, J.-B.; Thomas, T. Vitamin D in adults: GRIO guidelines. La Presse Médicale. 2011, 40, 673–682. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, W.B.; Lahore, H.; McDonnell, S.L.; Baggerly, C.A.; French, C.B.; Aliano, J.L.; Bhattoa, H.P. Evidence that Vitamin D Supplementation Could Reduce Risk of Influenza and COVID-19 Infections and Deaths. Nutrienrs 2020, 12, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annweiler, C.; Cao, Z.; Sabatier, J.-M. Point of view: Should COVID-19 patients be supplemented with vitamin D? Maturitas 2020, 140, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, P.C.; Stefanescu, S.; Smith, L. The role of vitamin D in the prevention of coronavirus disease 2019 infection and mortality. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1195–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-2019) R&D. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/blueprint/covid-19 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Vetel, J.M.; Leroux, R.; Ducoudray, J.M. [AGGIR. Practical use. Geriatric Autonomy Group Resources Needs]. Soins Gérontologie 1998, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Del Galy, A.S.; Bertrand, M.; Bigot, F.; Abraham, P.; Thomlinson, R.; Paccalin, M.; Beauchet, O.; Annweiler, C.; Del Galy, A.S.; Bigot, F.; et al. Vitamin D Insufficiency and Acute Care in Geriatric Inpatients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2009, 57, 1721–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochon, J.; Gondan, M.; Kieser, M. To test or not to test: Preliminary assessment of normality when comparing two independent samples. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, D.O.; Best, T.J.; Zhang, H.; Vokes, T.; Arora, V.; Solway, J. Association of Vitamin D Status and Other Clinical Characteristics With COVID-19 Test Results. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Avolio, A.; Avataneo, V.; Manca, A.; Cusato, J.; De Nicolò, A.; Lucchini, R.; Keller, F.; Cantù, M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations Are Lower in Patients with Positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghbooli, Z.; Sahraian, M.A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Pazoki, M.; Kafan, S.; Tabriz, H.M.; Hadadi, A.; Montazeri, M.; Nasiri, M.; Shirvani, A.; et al. Vitamin D sufficiency, a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D at least 30 ng/mL reduced risk for adverse clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, C.E.; Mackay, D.F.; Ho, F.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Niedzwiedz, C.L.; Jani, B.D.; Welsh, P.; Mair, F.S.; Gray, S.R.; et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, M.E.; Costa, L.M.E.; Barrios, J.M.V.; Díaz, J.F.A.; Miranda, J.L.; Bouillon, R.; Gomez, J.M.Q. Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical study. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 203, 105751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, A.R.; Jolliffe, D.A.; Hooper, R.L.; Greenberg, L.; Aloia, J.F.; Bergman, P.; Dubnov-Raz, G.; Esposito, S.; Ganmaa, D.; Ginde, A.A.; et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: Systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 2017, 356, i6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, J.K.; International Association for Gerontology and Geriatrics-Asia/Oceania Region; Chan, P.; Arai, H.; Park, S.C.; Gunaratne, P.S.; Setiati, S.; Assantachai, P. Prevention of COVID-19 in Older Adults: A Brief Guidance from the International Association for Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG) Asia/Oceania Region. J. Nutr. Heal. Aging 2020, 24, 471–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French National Academy of Medicine. Vitamin D and Covid-19—Press Release. Available online: http://www.academie-medecine.fr/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20.5.22-Vitamine-D-et-coronavirus-ENG.pdf. (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Kong, J.; Zhu, X.; Shi, Y.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y.; Bhan, I.; Zhao, Q.; Thadhani, R.; Li, Y.C. VDR Attenuates Acute Lung Injury by Blocking Ang-2-Tie-2 Pathway and Renin-Angiotensin System. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkman, R.; Jebbink, M.F.; Deijs, M.; Milewska, A.; Pyrc, K.; Buelow, E.; Van Der Bijl, A.; Van Der Hoek, L. Replication-Dependent Downregulation of Cellular Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 Protein Expression by Human Coronavirus NL63. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 1924–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annweiler, C.; Cao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Faucon, E.; Mouhat, S.; Kovacic, H.; Sabatier, J.-M. Counter-regulatory ‘Renin-Angiotensin’ System-based Candidate Drugs to Treat COVID-19 Diseases in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 20, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xue, Y.; Tan, G.; Niu, G. TWIRLS, an Automated Topic-Wise Inference Method Based on Massive Literature, Suggests a Possible Mechanism via ACE2 for the Pathological Changes in the Human Host after Coronavirus Infection. bioRxiv 2020. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J. Effect of Vitamin D on ACE2 and Vitamin D receptor expression in rats with LPS-induced acute lung injury. Chin. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 25, 1284–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, A.; Infante, M.; Ricordi, C. Editorial—Vitamin D status: A key modulator of innate immunity and natural defense from acute viral respiratory infections. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 4048–4052. [Google Scholar]

- Dancer, R.C.A.; Parekh, D.; Lax, S.; D’Souza, V.; Zheng, S.; Bassford, C.R.; Park, D.; Bartis, D.G.; Mahida, R.; Turner, A.M.; et al. Vitamin D deficiency contributes directly to the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Thorax 2015, 70, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanad, C.; García-Blas, S.; Tarazona-Santabalbina, F.; Sanchis, J.; Bertomeu-González, V.; Fácila, L.; Ariza, A.; Núñez, J.; Cordero, A. The Effect of Age on Mortality in Patients With COVID-19: A Meta-Analysis With 611,583 Subjects. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.; Carter, B.; Vilches-Moraga, A.; Quinn, T.J.; Braude, P.; Verduri, A.; Pearce, L.; Stechman, M.; Short, R.; Price, A.; et al. The effect of frailty on survival in patients with COVID-19 (COPE): A multicentre, European, observational cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e444–e451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Guidelines for optimizing design and analysis of clinical studies of nutrient effects. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All COVID-19 Participants (n = 77) | Study Groups | p-Value * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 Regular Vitamin D Supplementation (n = 29) | Group 2 Vitamin D Supplementation After COVID-19 Diagnosis (n = 16) | Group 3 Non-Supplemented Comparator Group (n = 32) | Overall (n = 77) | Group 1 Versus Group 3 (n = 61) | Group 2 Versus Group 3 (n = 48) | Group 1 Versus Group 2 (n = 45) | ||

| Demographical data | ||||||||

| Age (years), med (IQR) | 88 (85–92) | 88 (87–93) | 85 (84–89) | 88 (84–92) | 0.22 | 0.98 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| Female gender | 38 (49.4) | 20 (69.0) | 5(31.3) | 13 (40.6) | 0.02 | 0.027 | 0.52 | 0.015 |

| GIR score (/6), med (IQR) | 4 (2–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (2–5) | 0.36 | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.13 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Severe undernutrition † | 21 (27.3) | 9 (31.0) | 3 (18.8) | 9 (28.1) | 0.67 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.49 |

| Hematological and solid cancers | 27 (35.1) | 10 (34.5) | 4 (25.0) | 13 (40.6) | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.29 | 0.74 |

| Hypertension | 49 (63.6) | 18 (62.1) | 10 (62.5) | 21 (65.6) | 0.95 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.98 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 42 (54.5) | 13 (44.8) | 11 (68.8) | 18 (56.3) | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.12 |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%), med (IQR) | 6.2 (5.8–6.7) | 6.0 (5.5–6.6) | 6.4 (6.0–8.2) | 6.2 (5.9–6.7) | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.08 |

| Hospitalization | ||||||||

| Number of acute health issues at hospital admission, med (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.5 (2.0–5.0) | 2.5 (1.0–4.0) | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.62 |

| CRP at admission (mg/L), med (IQR) | 59.5 (19.5–135.0) | 44.0 (19.0–110.0) | 69.0 (15.5–140.0) | 59.0 (29.0–166.0) | 0.47 | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.63 |

| Use of antibiotics ‡ | 59 (76.6) | 23 (79.3) | 14 (87.5) | 22 (68.8) | 0.32 | 0.349 | 0.29 | 0.69 |

| Use of systemic corticosteroids | 13 (16.9) | 6 (20.7) | 2 (12.5) | 5 (15.6) | 0.79 | 0.607 | 1.00 | 0.69 |

| Use of pharmacological treatments of respiratory disorders || | 10 (13.0) | 1 (3.5) | 2 (12.5) | 7 (21.9) | 0.10 | 0.055 | 0.70 | 0.29 |

| COVID-19 outcomes | ||||||||

| Severe COVID-19 § | 17 (22.1) | 3 (10.3) | 4 (25.0) | 10 (31.3) | 0.14 | 0.047 | 0.75 | 0.23 |

| 14-day mortality | 15 (19.5) | 2 (6.9) | 3 (18.8) | 10 (31.3) | 0.06 | 0.017 | 0.50 | 0.33 |

| Severe COVID-19 * | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Interventions | |||

| Group 1: regular vitamin D supplementation | 0.08 | (0.01; 0.81) | 0.033 |

| Group 2: vitamin D supplementation initiated after COVID-19 diagnosis | 0.46 | (0.07; 2.85) | 0.40 |

| Group 3: no vitamin D supplementation | 1 | ||

| Age | 1.05 | (0.88; 1.25) | 0.61 |

| Female gender | 1.43 | (1.29; 7.13) | 0.66 |

| GIR score | 0.76 | (0.44; 1.33) | 0.33 |

| Severe undernutrition † | 0.42 | (0.07; 2.48) | 0.34 |

| History of cancer | 7.30 | (1.37; 38.8) | 0.02 |

| History of hypertension | 0.51 | (0.11; 2.33) | 0.39 |

| History of cardiomyopathy | 10.01 | (1.44; 69.88) | 0.02 |

| Glycated hemoglobin ‡ | 0.96 | (0.56; 1.63) | 0.87 |

| Number of acute health issues at hospital admission | 1.19 | (0.76; 1.88) | 0.45 |

| Use of antibiotics || | 1.12 | (0.18; 6.85) | 0.91 |

| Use of systemic corticosteroids | 2.53 | (0.34; 17.00) | 0.34 |

| Use of pharmacological treatments of respiratory disorders § | 0.26 | (0.02; 2.86) | 0.27 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Annweiler, G.; Corvaisier, M.; Gautier, J.; Dubée, V.; Legrand, E.; Sacco, G.; Annweiler, C., on behalf of the GERIA-COVID study group. Vitamin D Supplementation Associated to Better Survival in Hospitalized Frail Elderly COVID-19 Patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-Experimental Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113377

Annweiler G, Corvaisier M, Gautier J, Dubée V, Legrand E, Sacco G, Annweiler C on behalf of the GERIA-COVID study group. Vitamin D Supplementation Associated to Better Survival in Hospitalized Frail Elderly COVID-19 Patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-Experimental Study. Nutrients. 2020; 12(11):3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113377

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnnweiler, Gaëlle, Mathieu Corvaisier, Jennifer Gautier, Vincent Dubée, Erick Legrand, Guillaume Sacco, and Cédric Annweiler on behalf of the GERIA-COVID study group. 2020. "Vitamin D Supplementation Associated to Better Survival in Hospitalized Frail Elderly COVID-19 Patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-Experimental Study" Nutrients 12, no. 11: 3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113377

APA StyleAnnweiler, G., Corvaisier, M., Gautier, J., Dubée, V., Legrand, E., Sacco, G., & Annweiler, C., on behalf of the GERIA-COVID study group. (2020). Vitamin D Supplementation Associated to Better Survival in Hospitalized Frail Elderly COVID-19 Patients: The GERIA-COVID Quasi-Experimental Study. Nutrients, 12(11), 3377. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113377