Associations between Changes in Health Behaviours and Body Weight during the COVID-19 Quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Data Collection

2.2. Questionnaire and Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Issues

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization: Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Government of the Republic of Lithuania: Quarantine Announced throughout the Territory of the Republic of Lithuania (Attached Resolution). 2020. Available online: https://lrv.lt/en/news/quarantine-announced-throughout-the-territory-of-the-republic-of-lithuania-attached-resolution (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Balanzá-Martínez, V.; Atienza-Carbonell, B.; Kapczinski, F.; De Boni, R.B. Lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19—Time to connect. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 141, 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enterprise Lithuania. COVID-19 News for Business: Impact on Business. 2020. Available online: https://www.enterpriselithuania.com/en/services/covid-19-news-business/impact-on-business/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Yau, Y.H.C.; Potenza, M.N. Stress and eating behaviors. Minerva Endocrinol. 2013, 38, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anton, S.D.; Miller, P.M. Do negative emotions predict alcohol consumption, saturated fat intake, and physical activity in older adults? Behav. Modif. 2005, 29, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, P. The role of physical activity and exercise in obesity and weight management: Time for critical appraisal. J. Sport Health Sci. 2016, 5, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalligeros, M.; Shehadeh, F.; Mylona, E.K.; Benitez, G.; Beckwith, C.G.; Chan, P.A.; Mylonakis, E. Association of obesity with disease severity among patients with COVID-19. Obesity 2020, 28, 1200–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighter, J.; Phillips, M.; Hochman, S.; Sterling, S.; Johnson, D.; Francois, F.; Stachel, A. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for COVID-19 hospital admission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 896–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogero, M.M.; Calder, P.C. Obesity, inflammation, toll-like receptor 4 and fatty acids. Nutrients 2018, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Food and Nutrition Tips during Self-Quarantine. 2020. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/technical-guidance/food-and-nutrition-tips-during-self-quarantine?fbclid=IwAR1JRTDs6a0B08DlqfrJo17qvoba2X-W_QS7oqcTAryUgSWw5n5E3Kx_qQE)#article (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Molina-Montes, E.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; García-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Ruíz-López, M.D. Changes in dietary behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; García-Arellano, A.; Toledo, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Schröder, H.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: The PREDIMED trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report on a WHO Consultation; Report No. 894; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Alles, B.; Andreeva, V.A.; Baudry, J.; Charreire, H.; Deschamps, V.; Egnell, M.; et al. Diet and Physical Activity during the COVID-19 Lockdown Period (March–May 2020): Results from the French NutriNet-Sante Cohort Study. MedRxiv 2020. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.04.20121855v1 (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Pellegrini, M.; Ponzo, V.; Rosato, R.; Scumaci, E.; Goitre, I.; Benso, A.; Belcastro, S.; Crespi, C.; De Michieli, F.; Ghigo, E.; et al. Changes in weight and nutritional habits in adults with obesity during the “lockdown” period caused by the COVID-19 virus emergency. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianatos, M.; Azuma, A.M.; Gilliland, S.; Gottlieb, R. Food access, availability, and affordability in 3 Los Angeles communities, project CAFE, 2004–2006. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2010, 7, A27. [Google Scholar]

- Leigh-Hunt, N.; Bagguley, D.; Bash, K.; Turner, V.; Turnbull, S.; Valtorta, N.; Caan, W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017, 152, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J.T.; Hawkley, L.C.; Norman, G.J.; Berntson, G.G. Social isolation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 123, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, B.; Haesebaert, F.; Zante, E.; Benyamina, A.; Haesebaert, J.; Franck, N. Global changes and factors of increase in caloric/salty food, screen, and substance use, during the early COVID-19 containment phase in France: A general population online survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 6, e19630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.D.; Fischer, S.; Smith, G.T.; Miller, J.D. The influence of negative urgency, attentional bias, and emotional dimensions on palatable food consumption. Appetite 2016, 100, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlMughamis, N.; AlAsfour, S.; Mehmood, S. Poor eating habits and predictors of weight gain during the COVID-19 quarantine measures in Kuwait: A cross sectional study. F1000Research 2020, 9, 914. Available online: https://f1000research.com/articles/9-914/v1 (accessed on 18 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary choices and habits during COVID-19 lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalopoulou, C.; Stubbs, B.; Kralj, C.; Koukounari, A.; Prince, M.; Prina, A.M. Physical activity and healthy ageing: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 38, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bann, D.; Villadsen, A.; Maddock, J.; Hughes, A.; Ploubidis, G.; Silverwood, R.; Patalay, P. Changes in the Behavioural Determinants of Health during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Gender, Socioeconomic and Ethnic Inequalities in 5 British Cohort Studies. MedRxiv 2020. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.29.20164244v1 (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Hills, A.P.; Byrne, N.M.; Lindstrom, R.; Hill, J.O. ‘Small changes’ to diet and physical activity behaviors for weight management. Obes. Facts 2013, 6, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonnet, A.; Chetboun, M.; Poissy, J.; Raverdy, V.; Noulette, J.; Duhamel, A.; Labreuche, J.; Mathieu, D.; Pattou, F.; Jourdain, M.; et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020, 28, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naja, F.; Hamadeh, R. Nutrition amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A multi-level framework for action. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1117–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 298 | 12.2 |

| Female | 2149 | 87.8 |

| Age groups | ||

| 18–35 | 982 | 40.1 |

| 36–50 | 898 | 36.7 |

| ≥51 | 567 | 23.2 |

| Education | ||

| University | 1738 | 71.0 |

| Lower | 709 | 29.0 |

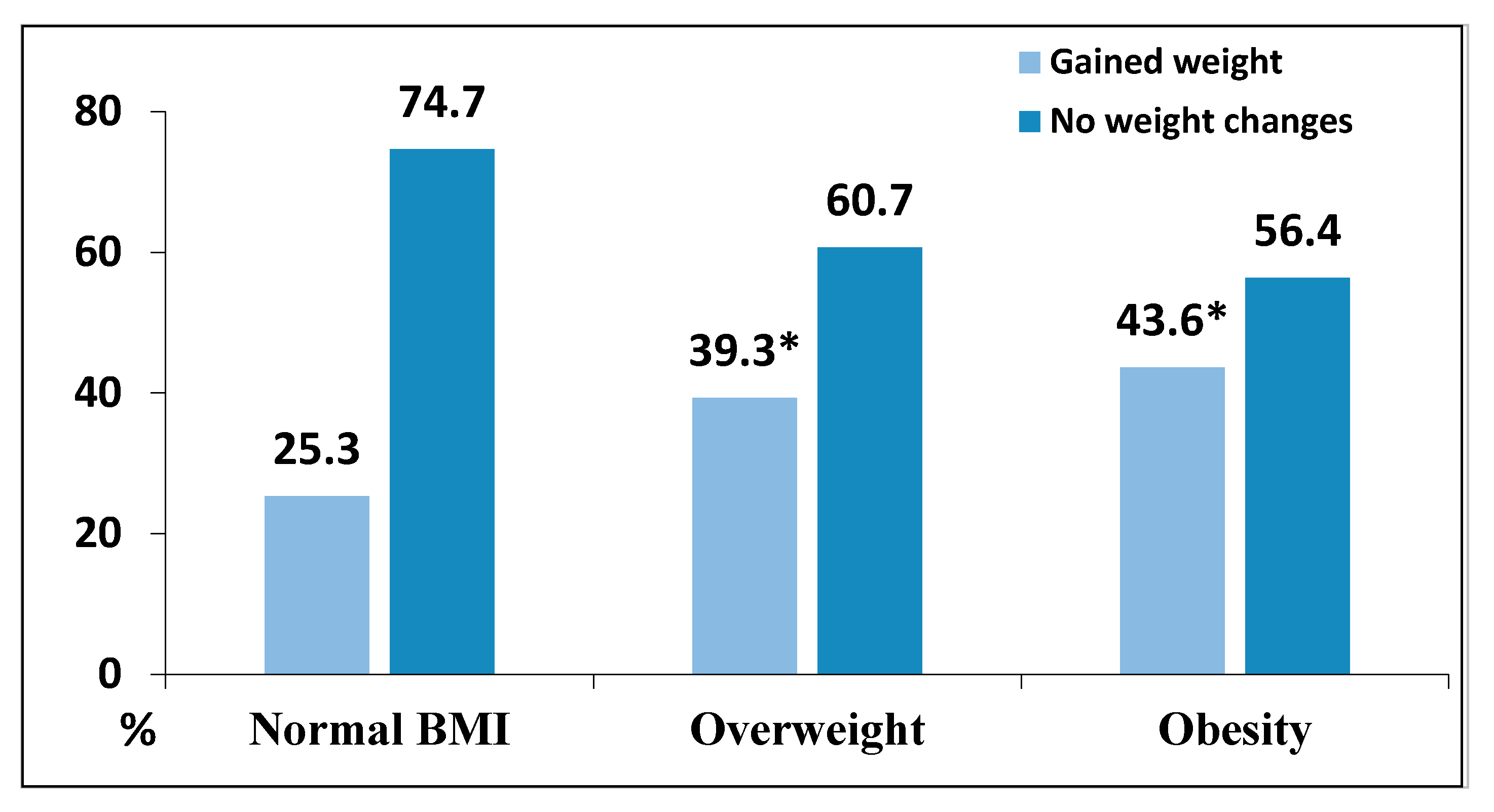

| Body mass index | ||

| <25 kg/m2 | 1458 | 59.8 |

| 25–29 kg/m2 | 679 | 27.8 |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 303 | 12.4 |

| Weight changes during the quarantine | ||

| Gained | 771 | 31.5 |

| No changes/didn’t know | 1676 | 68.5 |

| Health Behaviours | Changes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased | Decreased | Remains as Usual | |

| Food intake | |||

| Vegetables | 18.8 | 15.0 | 66.2 |

| Fruits | 22.1 | 14.7 | 63.2 |

| Pulses | 9.1 | 8.5 | 82.4 |

| Fish-seafood | 7.5 | 14.3 | 78.3 |

| Red meats, hamburgers, sausages | 12.2 | 17.9 | 69.9 |

| Carbonated and/or sugary beverages (soda, cola, tonic, bitter) | 8.5 | 19.4 | 72.0 |

| Commercial (non-homemade) pastries such as cookies, custards, sweets | 18.9 | 26.0 | 55.2 |

| Homemade pastries such as cookies, custards, sweets or cakes | 37.7 | 11.5 | 50.8 |

| Fast food | 6.7 | 41.3 | 51.9 |

| Fried food | 20.6 | 8.3 | 71.1 |

| Eating habits | |||

| Snacking | 45.1 | 9.8 | 45.1 |

| Cooking more often than before the quarantine | 62.1 (yes) | 1.3 (no, less often) | 36.5 (as usual) |

| Eat more than usual | 49.4 (yes) | - | 50.6 (as usual) |

| Other lifestyle habits | |||

| Alcoholic beverages consumption | 14.2 | 15.9 | 69.9 |

| Physical activity | 14.3 | 60.6 | 19.3 |

| Changes in Health Behaviours | Weight Change | p-Value * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gained | No Changes/Doesn’t Know | ||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Food intake | |||||

| Vegetables decreased | 163 | 21.1 | 203 | 12.1 | 0.001 |

| Fruits decreased | 144 | 18.7 | 216 | 12.9 | 0.001 |

| Red meats, hamburgers, sausages increased | 157 | 20.4 | 141 | 8.4 | 0.001 |

| Carbonated and/or sugary beverages increased | 116 | 15.0 | 93 | 5.5 | 0.001 |

| Commercial pastries increased | 241 | 31.3 | 221 | 13.2 | 0.001 |

| Homemade pastries increased | 405 | 52.5 | 517 | 30.8 | 0.001 |

| Fast food increased | 95 | 12.3 | 70 | 4.2 | 0.001 |

| Fried food increased | 251 | 32.6 | 253 | 15.1 | 0.001 |

| Eating habits | |||||

| Snacking increased | 566 | 73.4 | 537 | 32.0 | 0.001 |

| Cooking more often than before the quarantine | 548 | 71.1 | 972 | 58.0 | 0.001 |

| Eat more than usual | 650 | 84.3 | 560 | 33.4 | 0.001 |

| Other lifestyle habits | |||||

| Alcoholic beverages consumption increased | 161 | 20.9 | 187 | 11.2 | 0.001 |

| Physical activity decreased | 657 | 85.2 | 967 | 57.7 | 0.001 |

| Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.37 (1.04–1.80) | 0.025 | 1.52 (1.08–2.14) | 0.015 |

| Age groups | ||||

| 18–35 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 36–50 | 1.14 (0.94–1.39) | 0.173 | 1.36 (1.06–1.73) | 0.014 |

| ≥51 | 1.08 (0.86–1.35) | 0.483 | 1.80 (1.35–2.39) | 0.001 |

| Education | ||||

| University | 1 | 1 | ||

| Lower | 1.18 (0.93–11.42) | 1.172 | 1.20 (0.96–1.51) | 0.113 |

| Intake of vegetables decreased * | 1.94 (1.55–2.44) | 0.001 | 1.12 (0.82–1.53) | 0.484 |

| Intake of fruits decreased * | 1.55 (1.23–1.95) | 0.001 | 1.12 (0.81–1.52) | 0.530 |

| Intake of red meat increased * | 2.78 (2.17–3.56) | 0.001 | 1.03 (0.75–1.40) | 0.871 |

| Intake of carbonated or sugary drinks increased * | 3.01 (2.26–4.02) | 0.001 | 1.44 (1.01–2.06) | 0.049 |

| Intake of commercial pastries increased * | 2.99 (2.43–3.68) | 0.001 | 1.20 (0.92–1.56) | 0.184 |

| Intake of homemade pastries increased * | 2.48 (2.08–2.95) | 0.001 | 1.56 (1.25–1.95) | 0.001 |

| Intake of fast food increased * | 3.22 (2.33–4.44) | 0.001 | 1.62 (1.09–2.43) | 0.018 |

| Intake of fried food increased * | 2.71 (2.22–3.32) | 0.001 | 1.15 (0.89–1.50) | 0.287 |

| Snacking increased * | 5.85 (4.84–7.08) | 0.001 | 1.55 (1.20–2.01) | 0.001 |

| Eating more than usual * | 10.70 (8.60–13.23) | 0.001 | 5.68 (4.30–7.51) | 0.001 |

| Physical activity decreased * | 4.22 (3.38–5.27) | 0.001 | 3.24 (2.53–4.16) | 0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption increased * | 2.10 (1.66–2.64) | 0.001 | 1.47 (1.11–1.95) | 0.008 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kriaucioniene, V.; Bagdonaviciene, L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Petkeviciene, J. Associations between Changes in Health Behaviours and Body Weight during the COVID-19 Quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103119

Kriaucioniene V, Bagdonaviciene L, Rodríguez-Pérez C, Petkeviciene J. Associations between Changes in Health Behaviours and Body Weight during the COVID-19 Quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet Study. Nutrients. 2020; 12(10):3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103119

Chicago/Turabian StyleKriaucioniene, Vilma, Lina Bagdonaviciene, Celia Rodríguez-Pérez, and Janina Petkeviciene. 2020. "Associations between Changes in Health Behaviours and Body Weight during the COVID-19 Quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet Study" Nutrients 12, no. 10: 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103119

APA StyleKriaucioniene, V., Bagdonaviciene, L., Rodríguez-Pérez, C., & Petkeviciene, J. (2020). Associations between Changes in Health Behaviours and Body Weight during the COVID-19 Quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet Study. Nutrients, 12(10), 3119. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103119