Use of Grape Pomace Phenolics to Counteract Endogenous and Exogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation End-Products

Abstract

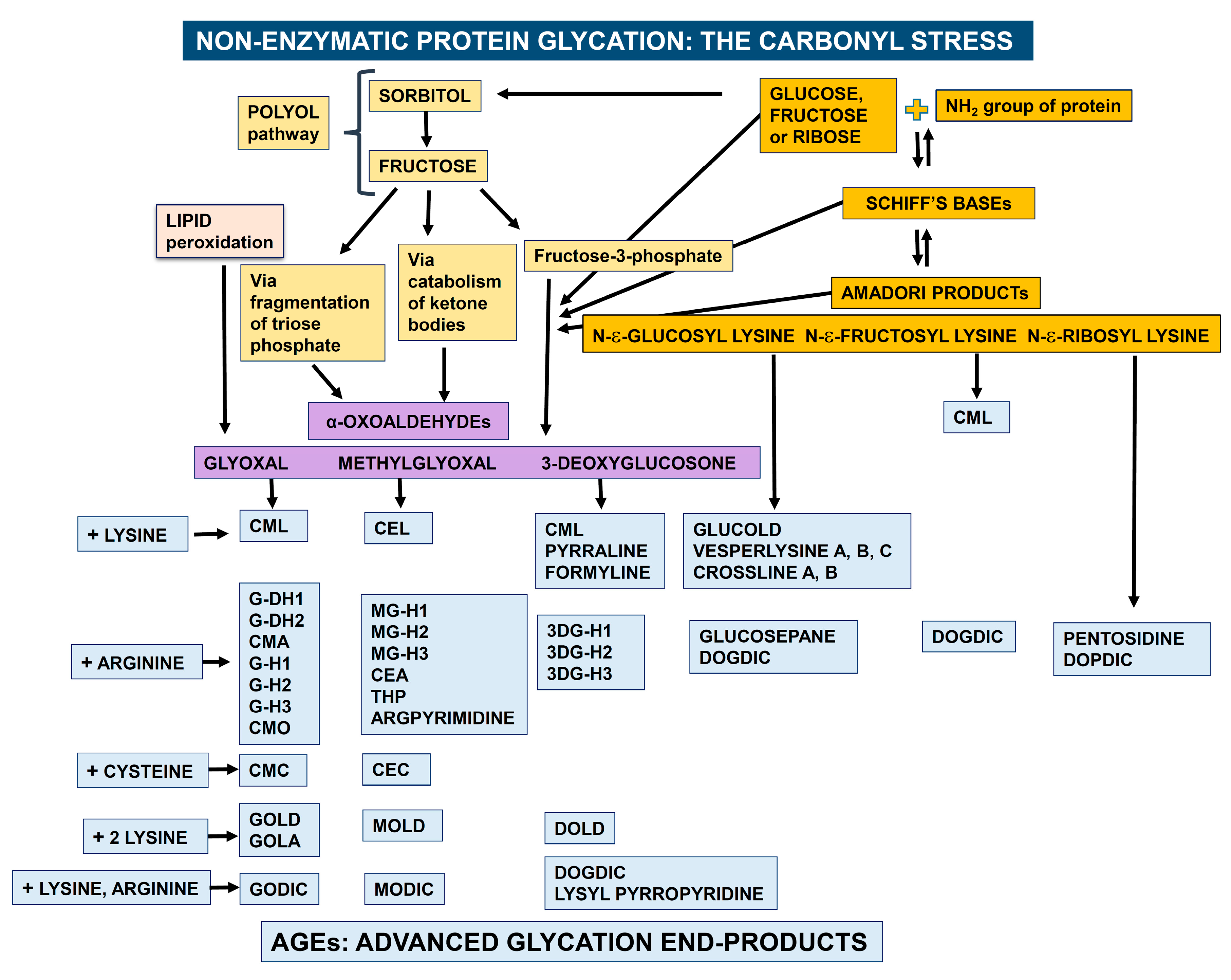

1. Endogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs)

- CML: Nε-(carboxymethyl) lysine

- G-DH1: Nẟ-(3,4-dihydroxy-1-imidazolidin-2-yl) ornithine

- G-DH2: 5-(4,5-dihydroxy-2-imino-1-imidazolidinyl) norvaline

- CMA: Nω-(carboxymethyl) arginine

- G-H1: Nẟ-(5-hydro-4-imidazolon-2-yl) ornithine

- G-H2: 5-(2-amino-5-hydro-4-imidazolon-1-yl) norvaline

- G-H3: 5-(2-amino-4-hydro-5-imidazolon-1-yl) norvaline

- CMO: Nẟ-(carboxymethyl) ornithine

- CMC: S-(carboxymethyl) cysteine

- GOLD: glyoxal-lysine dimer, 6-{1-[(5S)-5-ammonio-6-oxido-6-oxohexyl]imidazolium-3-yl}-L-norleucine

- GOLA: Nε-(2-{[(5S)-5-ammonio-6-oxido-6-oxohexyl] amino}-2-oxoethyl)-L-lysine

- GODIC: Nε-(2-{[(4S)-4-ammonio-5-oxido-5-oxopentyl]amino}-3,5-dihydro-4H-imidazol-4-ylidene)-L-lysine

- CEL: Nε-(carboxylethyl) lysine

- MG-H1: Nẟ-(5-methyl-4-imidazolon-2-yl)-L ornithine

- MG-H2: 2-amino-5-(2-amino-5-hydro-5-methyl-4-imidazolon-1-yl)pentanoic acid

- MG-H3: 2-amino-5-(2-amino-4-hydro-4-methyl-5-imidazolon-1-yl)pentanoic acid

- CEA: Nω-(carboxyethyl) arginine

- THP: Nẟ-(4-carboxy-4,6-dimethyl-5,6-dihydroxy-1,4,5,6-tetrahydropyrimidine-2-yl)-L-ornithine

- ARGPYRIMIDINE: Nẟ-(5-hydroxy-4,6-dimethylpyrimidine-2-yl)-L-ornithine

- CEC: S-carboxyethylcysteine

- MOLD: methylglyoxal lysine dimer, 6-{1-[(5S)-5-ammonio-6-oxido-6-oxohexyl]-4-methyl-imidazolium-3-yl}-L-norleucine

- MODIC: 2-ammonio-6-({2–[4-ammonio-5-oxido-5-oxopently)amino]-4-methyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-5-ylidene}amino)hexanoate

- CML: Nε-(carboxymethyl) lysine

- PYRRALINE: 6-(2-formyl-5-hydroxymethyl-1-pyrrolyl)-L-norleucine

- FORMYLINE: 6-(2-formyl-1-pyrrolyl)-L-norleucine

- 3DG-H1: Nẟ-[5-hydro-5-(2,3,4-trihydroxybutyl)-4-imidazolon-2-yl] ornithine

- 3DG-H2: 5-[2-amino-5-hydro-5-(2,3,4-trihydroxybutyl)-4-imidazolon-1-yl] norvaline

- 3DG-H3: 5-[2-amino-4-hydro-4-(2,3,4-trihydroxybutyl)-5-imidazolon-1-yl] norvaline

- DOLD: 1,3-di(Nε-lysino)-4-(2,3,4-trihydroxybutyl)-imidazolium

- DOGDIC: Nε-{2-{[(4S)-4-ammonio-5-oxido-5-oxopentyl]amino}-5-[(2S,3R)-2,3,4-trihydroxybutyl]-3,5-dihydro-4H-imidazol-4-ylidene}-L-lysinate

- LYSYL-PYRROPYRIDINE: lysyl-3,3a,8,8a-tetrahydro-3a-hydroxy-2-(1,2-dihydroxyethyl)-5 hydroxymethyl-2H-furo [3′,2: 4,5]pyrrolo-[2,3-c]-pyridinium

- GLUCOSEPANE: 2-acetylamino-5-[(4-butyl-6,7-dihydroxy-4,5,6,7,8,8ahexahydroimidazo [4,5-b]azepin-2-yl)amino]-pentanoic acid

- PENTOSIDINE: 6-[2-[[(4S)-4-amino-5-hydroxy-5-oxopentyl] amino]-4-imidazo [4,5-b]pyridinyl]-L-norleucine

- GLUCOLD: 1,3-bis-(5-amino-5-carboxypentyl)-4-(1,2,3,4-tetrahydroxybutyl)-3H-imidazolium

- CROSSLINES A and B N-diacetates: (3R,4S)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-[(1S or 1R,2S,3R)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroxybutyl]-1,7-bis[6-(N-acetyl-L-norleucyl)]-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-1,7-naphthyridinium chloride

- DOPDIC: Nε-{2-{[(4S)-4-ammonio-5-oxido-5-oxopentyl] amino}-5-[(2S)-2,3-dihydroxypropyl] 3,5-dihydro-4H-imidazol-4-ylidene}-L-lysinate

- VESPERLYSINE A: 6-hydroxy-1,4-di{6-(L-norleucyl)}-1H-pyrrolo[3,2-b] pyridinium

- VESPERLYSINE B: 6-hydroxy-5-methyl-1,4-di{6-(L-norleucyl)}-1H-pyrrolo[3,2-b] pyridinium

- VESPERLYSINE C: 5-hydroxymethyl-1,6-di{6-(L-norleucyl)}-1H-pyrrolo[3,4-b] pyridinium

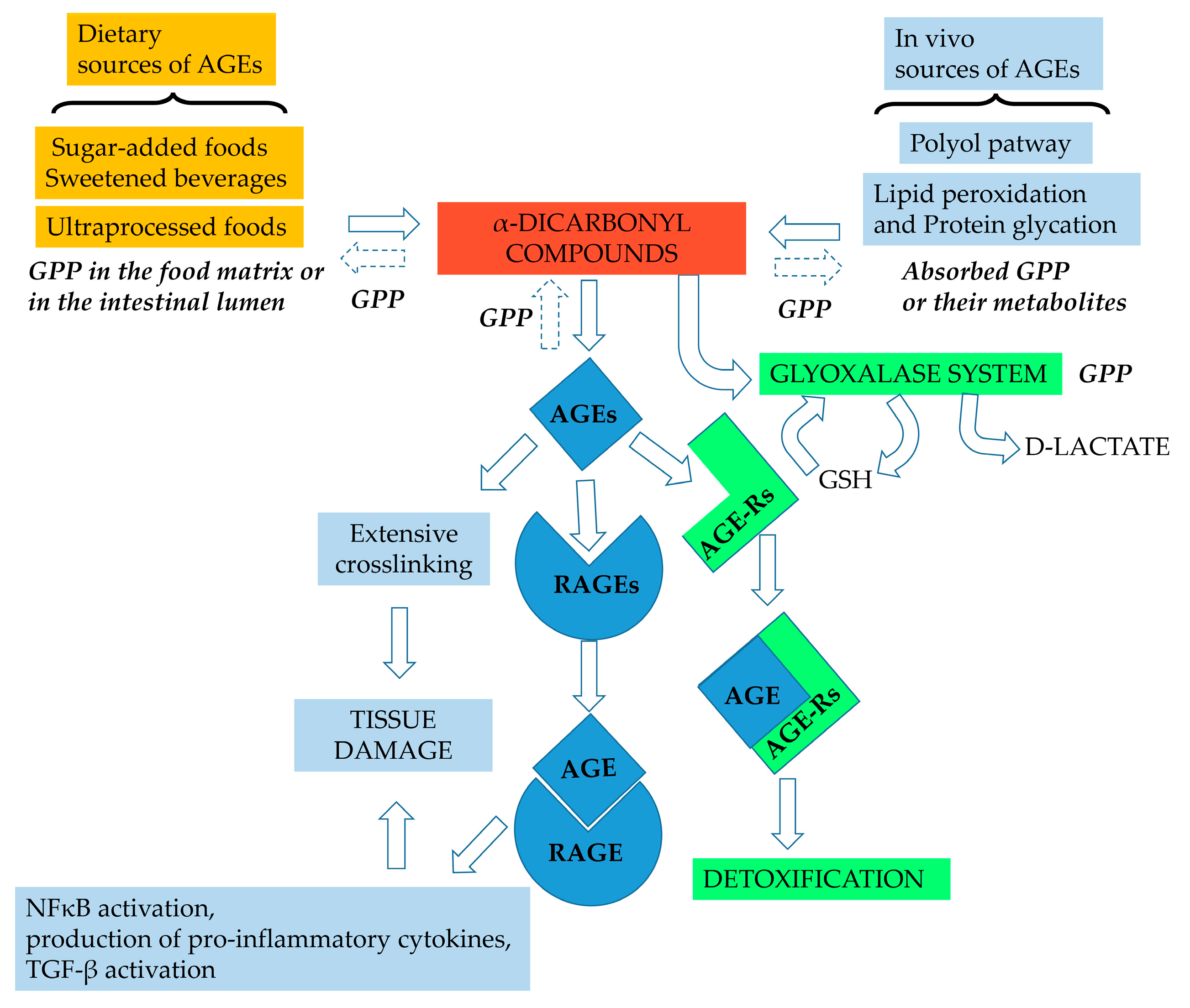

2. Effect of Diet on the Formation of AGEs

3. Detection of AGEs

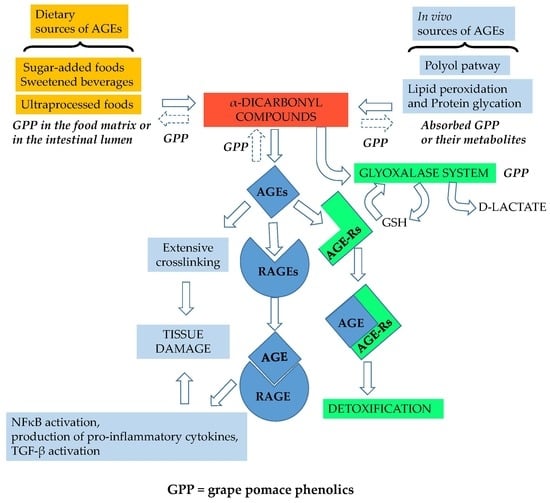

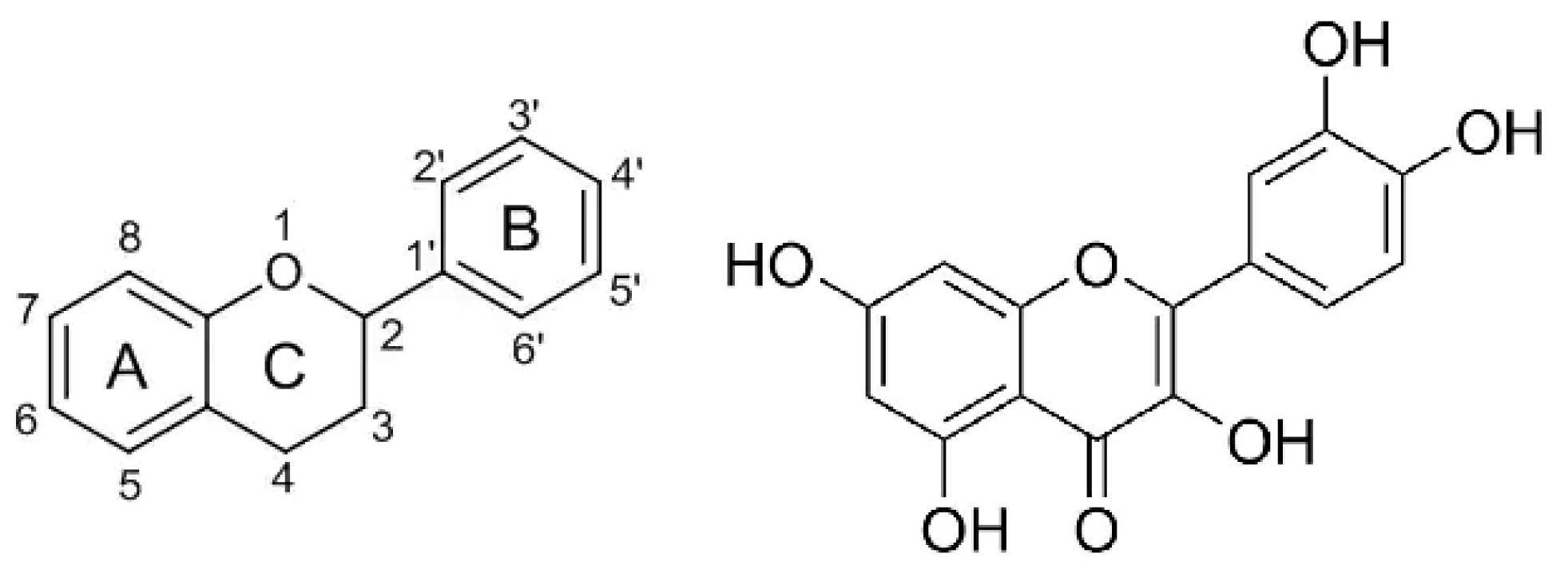

4. Grape Pomace Phenolics as Inhibitors of Protein Glycation—Mechanisms of Action

5. Grape Pomace Phenolics as Inhibitors of Protein Glycation—In Vivo Studies

6. Food Formulation with Grape Pomace Phenolics as a Strategy to Counteract AGE Formation

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saraswat, M.; Reddy, P.Y.; Muthenna, P.; Reddy, G.B. Prevention of non-enzymatic glycation of proteins by dietary agents: Prospects for alleviating diabetic complications. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 101, 1714–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, N.M.J.; Beulens, J.W.J.; van Dieren, S.; Scheijen, J.L.J.M.; van der A, D.L.; Spijkerman, A.M.W.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Schalkwijk, C.G. Plasma advanced glycation end products are associated with incident cardiovascular events in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A case-cohort study with a median follow-up of 10 years (EPIC-NL). Diabetes 2015, 64, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, N.M.; Wouters, K.; Huijberts, M.S.; Gijbels, M.J.; Sluimer, J.C.; Scheijen, J.L.; Heeneman, S.; Biessen, E.A.; Daemen, M.J.; Brownlee, M.; et al. Higher levels of advanced glycation endproducts in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques are associated with a rupture-prone phenotype. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agalou, S.; Ahmed, N.; Babaei-Jadidi, R.; Dawnay, A.; Thornalley, P.J. Profound mishandling of protein glycation degradation products in uremia and dialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 1471–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollenbach, M. The Role of Glyoxalase-I (Glo-I), Advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), and their receptor (RAGE) in chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragno, M.; Mastrocola, R. Dietary sugars and endogenous formation of advanced glycation endproducts: Emerging mechanisms of disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Barden, A.; Mori, T.; Beilin, L. Advanced glycation end-products: A review. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vistoli, G.; De Maddis, D.; Cipak, A.; Zarkovic, N.; Carini, M.; Aldini, G. Advanced glycoxidation and lipoxidation end products (ages and ales): An overview of their mechanisms of formation. Free Radic. Res. 2013, 47 (Suppl. S1), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelen, L.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Schalkwijk, C.G. Current therapeutic interventions in the glycation pathway: Evidence from clinical studies. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2013, 15, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornalley, P.J. Cell activation by glycated proteins. AGE receptors, receptor recognition factors and functional classification of AGEs. Cell. Mol. Biol. 1998, 44, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vlassara, H.; Li, Y.M.; Imani, F.; Wojciechowicz, D.; Yang, Z.; Liu, F.T.; Cerami, A. Identification of galectin-3 as a high-affinity binding protein for advanced glycation end products (AGE): A new member of the AGE-receptor complex. Mol. Med. 1995, 1, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.M.; Mitsuhashi, T.; Wojciechowicz, D.; Shimizu, N.; Li, J.; Stitt, A.; He, C.; Banerjeet, D.; Vlassara, H. Molecular identity and cellular distribution of advanced glycation endproduct receptors: Relationship of p60 to OST-48 and p90 to 80K-H membrane proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 11047–11052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santel, T.; Pflug, G.; Hemdan, N.Y.A.; Schafer, A.; Hollenbach, M.; Buchold, M.; Hintersdorf, A.; Lindner, I.; Otto, A.; Bigl, M.; et al. Curcumin inhibits glyoxalase 1—A possible link to its anti-Inflammatory and anti-tumor activity. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Andrade, C.; Seiquer, I.; Navarro, M.P.; Morales, F.J. Maillard reaction indicators in diets usually consumed by adolescent population. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribarri, J.; Woodruff, S.; Goodman, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, X.; Pyzik, R.; Yong, A.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuohy, K.M.; Hinton, D.J.; Davies, S.J.; Crabbe, M.J.; Gibson, G.R.; Ames, J.M. Metabolism of Maillard reaction products by the human gut microbiota–Implications for health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006, 50, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribarri, J.; Cai, W.; Peppa, M.; Goodman, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Striker, G.; Vlassara, H. Circulating glycotoxins and dietary advanced glycation endproducts: Two links to inflammatory response, oxidative stress, and aging. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlassara, H.; Cai, W.; Tripp, E.; Pyzik, R.; Yee, K.; Goldberg, L.; Tansman, L.; Chen, X.; Mani, V.; Fayad, Z.A.; et al. Oral age restriction ameliorates insulin resistance in obese individuals with the metabolic syndrome: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2016, 59, 2181–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellow, N.J.; Savige, G.S. Dietary advanced glycation end-product restriction for the attenuation of insulin resistance, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction: A systematic review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bains, Y.; Gugliucci, A.; Caccavello, R. Advanced glycation endproducts form during ovalbumin digestion in the presence of fructose: Inhibition by chlorogenic acid. Fitoterapia 2017, 120, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeChristopher, L.R.; Uribarri, J.; Tucker, K.L. Intake of high fructose corn syrup sweetened soft drinks is associated with prevalent chronic bronchitis in U.S. Adults, ages 20–55 y. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeChristopher, L.R.; Uribarri, J.; Tucker, K.L. Intakes of apple juice, fruit drinks and soda are associated with prevalent asthma in us children aged 2–9 years. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Liu, T.; Sun, D.W. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) in foods and their detecting techniques and methods: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 82, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, J.M.; Ahmad, M.; Choi, I.; Ahmad, N.; Farhan, M.; Tatyana, G.; Shahab, U. Critical review recent advances in detection of AGEs: Immunochemical, bioanalytical and biochemical approaches. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N.; Argirov, O.K.; Minhas, H.S.; Cordeiro, C.A.A.; Thornalley, P.J. Assay of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs): Surveying AGEs by chromatographic assay with derivatization by 6-aminoquinolyl-N-hydroxysuccinimidyl-carbamate and application to Nε-carboxymethyl-lysine-and nε-(1-carboxyethyl) lysine-modified albumin. Biochem. J. 2002, 364, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N.; Mirshekarsyahkal, B.; Kennish, L.; Karachalias, N.; Babaeijadidi, R.; Thornalley, P.J. Assay of advanced glycation endproducts in selected beverages and food by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mildner-Szkudlarz, S.; Siger, A.; Szwengiel, A.; Bajerska, J. Natural compounds from grape by-products enhance nutritive value and reduce formation of CML in model muffins. Food Chem. 2015, 172, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.H.; Yen, G.C. Inhibitory effect of naturally occurring flavonoids on the formation of advanced glycation endproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3167–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, H.; Wang, T.; Managi, H.; Yoshikawa, M. Structural requirements of flavonoids for inhibition of protein glycation and radical scavenging activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 5317–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesias, M.; Navarro, M.; Gokmen, V.; Morales, F.J. Antiglycative effect of fruit and vegetable seed extracts: Inhibition of age formation and carbonyl-trapping abilities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2037–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Y.; Sedighi, R.; Ho, C.T.; Sang, S. Essential structural requirements and additive effects for flavonoids to scavenge methylglyoxal. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 3202–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zheng, T.; Sang, S.; Lv, L. Quercetin inhibits advanced glycation end product formation by trapping methylglyoxal and glyoxal. J Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 12152–12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sri Harsha, P.S.C.; Mesias, M.; Lavelli, V.; Morales, F.J. Grape skin extracts from winemaking by-products as a source of trapping agents for reactive carbonyl species. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sri Harsha, P.S.; Lavelli, V.; Scarafoni, A. Protective ability of phenolics from white grape vinification by-products against structural damage of bovine serum albumin induced by glycation. Food Chem. 2014, 156, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sri Harsha, P.S.C.; Gardana, C.; Simonetti, P.; Spigno, G.; Lavelli, V. Characterization of phenolics, in vitro reducing capacity and anti-glycation activity of red grape skins recovered from winemaking by-products. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 140, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.F.; Dragsted, L.O.; Daneshvar, B.; Lauridsen, S.T.; Hansen, M.; Sandstrom, B. The effect of grape-skin extract on oxidative status. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, P.; Laight, D.; Rooprai, H.K.; Shaw, K.M.; Cummings, M. Effects of grape seed extract in type 2 diabetic subjects at high cardiovascular risk: A double blind randomized placebo controlled trial examining metabolic markers, vascular tone, inflammation, oxidative stress and insulin sensitivity. Diabet. Med. 2009, 26, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé-Carneiro, T.; Gonzálvez, M.; Larrosa, M.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; García-Almagro, F.J.; Ruiz-Ros, J.A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; García-Conesa, M.T.; Espín, J.C. Grape resveratrol increases serum adiponectin and downregulates inflammatory genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells: A triple-blind, placebo-controlled, one-year clinical trial in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2013, 27, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokayem, M.; Blond, E.; Vidal, H.; Lambert, K.; Meugnier, E.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Coudray, C.; Pesenti, S.; Luyton, C.; Lambert-Porcheron, S.; et al. Grape polyphenols prevent fructose-induced oxidative stress and insulin resistance in first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquiaga, I.; D’Acuna, S.; Perez, D.; Dicenta, S.; Echeverria, G.; Rigotti, A.; Leighton, F. Wine grape pomace flour improves blood pressure, fasting glucose and protein damage in humans: A randomized controlled trial. Biol. Res. 2015, 48, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Weickert, M.O.; Qureshi, S.; Kandala, N.B.; Anwar, A.; Waldron, M.; Shafie, A.; Messenger, D.; Fowler, M.; Jenkins, G.; et al. Improved glycemic control and vascular function in overweight and obese subjects by glyoxalase 1 inducer formulation. Diabetes 2016, 65, 2282–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Eynde, M.D.G.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Scheijen, J.; Hanssen, N.M.J.; Dower, J.I.; Afman, L.A.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Hollman, P.C.H.; Schalkwijk, C.G. Quercetin, but not epicatechin, decreases plasma concentrations of methylglyoxal in adults in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial with pure flavonoids. J. Nutr. 2018, 148, 1911–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Ma, J.; Cheng, K.W.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, M. The effects of grape seed extract fortification on the antioxidant activity and quality attributes of bread. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildner-Szkudlarz, S.; Siger, A.; Szwengiel, A.; Przygonski, K.; Wojtowicz, E.; Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R. Phenolic compounds reduce formation of n(epsilon)-(carboxymethyl)lysine and pyrazines formed by Maillard reactions in a model bread system. Food Chem. 2017, 231, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, F.; Wang, M. Antioxidant and antiglycation activity of selected dietary polyphenols in a cookie model. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2014, 62, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Gwyneth Tan, Y.X.; Leong, L.P.; Zhou, W. Steamed bread enriched with quercetin as an antiglycative food product: Its quality attributes and antioxidant properties. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 3398–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelli, V.; Sri Harsha, P.S.C.; Torri, L.; Zeppa, G. Use of winemaking by-products as an ingredient for tomato puree: The effect of particle size on product quality. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelli, V.; Sri Harsha, P.S.C.; Piochi, M.; Torri, L. Sustainable recovery of grape skins for use in an apple beverage with antiglycation properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavelli, V.; Sri Harsha, P.S.C. Microencapsulation of grape skin phenolics for pH controlled release of antiglycation agents. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product and Daily Dose | Intake of Phenolics (Per Day) | Subjects | Trial Type | Duration | Outcome | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red grape skin extract powder (600 mg) | Total phenolic 31 mg | n = 15 Healthy | Crossover randomized | 2 weeks | ˃Glutathione reductase activity and glutathione peroxidase activity No effect on superoxide dismutase or catalase No effect on 2-aminoadipic semialdehyde, a plasma protein oxidation product No effect on malondialdehyde, a marker of lipoprotein oxidation. | [36] |

| Grape seed extract 2 tablets | Total phenolics 0.6 g | n = 32 Type-2 diabetic subjects | Crossover randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 4 weeks | <Fructosamine ˃High sensitivity C reactive protein ˃Reduced glutathione | [37] |

| Grape phenolics or grape phenolics + resveratrol 350 mg | ~25 mg anthocyanins, ~1 mg flavonols, ~40 mg procyanidins, and ~0.8 mg hydroxycinnamic acids, or the same + 8.1 mg resveratrol | n = 75 Patients with stable coronary artery disease | Crossover randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled | 1 year | ˃Serum adiponectin <Plasminogen activator ˃Inhibitor type 1 <Atherothrombotic signals in peripheral blood mononuclear No effect on glycated haemoglobin | [38] |

| Grape polyphenols 6 capsules | Total phenolics 2 g | n = 38 Healthy overweight/obese first-degree relatives of type-2 diabetic subjects | Crossover randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 8 weeks | <Urinary F2-isoprostanes, muscle thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, muscle protein carbonylation ˃Hepatic insulin sensitivity | [39] |

| Red grape pomace (20 g) | Total phenolics 0.82 g | n = 38 Metabolic syndrome | Crossover randomized, placebo-controlled | 16 weeks | <Carbonyl groups in plasma proteins (protein damage) | [40] |

| Pure compounds | Trans-resveratrol (90 mg) + hesperidine (120 mg) | n = 29 Overweight and obese subjects | Crossover randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 8 weeks | ˃Expression and activity of glyoxalase-1 <Plasma methylglyoxal and total body methylglyoxal-protein glycation <Fasting and postprandial plasma glucose ˃Insulin sensitivity ˃Markers for vascular health | [41] |

| Pure compounds | Quercetin 3-glucoside (160 mg) (−)-epicatechin (100 mg) | n = 37 Healthy | Crossover randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 4 weeks | <Plasma methylglyoxal for quercetin 3-glucoside, no change in glyoxal, 3-deoxyglucosone and free and protein-bound AGE No effect for epicatechin | [42] |

| Food | Phenolic Source | Identified Phenolics | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat bread | Grape seed extract powder Integration: 2 g/kg bread | n.d. | CML level was 35 mg/kg in the bread crust of the control Addition of grape seed extract caused a 50% decrease in CML level | [43] |

| Wheat bread | Purified phenolics Integration: 1–20 g/kg flour | Flavanol: catechin Flavonol: quercetin Phenolic acids: gallic acid, ferulic acid, caffeic acids | CML level was 49.71 mg/kg in the bread crust of the control and 15.09 mg/kg in the bread crumb of the control Phenolics were found to significantly reduce CML (31.77%–87.56%) | [44] |

| Model cookie | Purified phenolics Integration: 25 g/kg | Flavonol: quercetin Flavanone: naringenin Flavanol: epicatechin Phenolic acids: rosmarinic acid, chlorogenic acid | Inhibition of fluorescent AGE formation was 80% for quercetin and ˂20% for naringenin, epicatechin, rosmarinic acid, chlorogenic acid | [45] |

| Muffin | Red grape pomace Integration: 200 g/kg | Phenolic acids: gallic acid Flavanols: catechin, epicatechin, oligomeric procyanidins Flavonols: quercetin 3-β-d-glucoside | CML level in the control muffins was 0.79–25.55 mg/kg depending on the receipt Red grape pomace decreased the level of CML up to 100% | [27] |

| Bread | Quercetin Integration: 12–36 g/kg | Flavonol: quercetin | Quercetin conferred antiglycation activity to bread | [46] |

| Tomato puree | White grape skin Integration: 30 g/kg | Flavonols: rutin, quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin, kaempferol 3-O-galactoside, kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, kaempferol Flavanone: naringenin Flavanols: oligomeric procyanidins | Addition of grape skins caused a 2.5-fold increase in the in vitro antiglycation activity of tomato (8 mmol catechin equivalents/kg in the fortified puree) | [47] |

| Apple puree | Red grape skin Integration: 30 g/kg | Anthocyanins: delphinidin 3-O-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-glucoside, petunidin 3-O-glucoside, peonidin 3-O-glucoside, malvidin 3-O-glucoside Flavanols: catechin, epicatechin, procyanidin B2, procyanidin B1, oligomeric proanthocyanidins Phenolic acids: chlorogenic acid Dihydrochalcones: phloretin-2-O-xyloglucoside, phloridzin Flavonols: quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, quercetin, kaempferol | Addition of grape skins caused a 2.0-fold increase in the in vitro antiglycation activity of apple puree (69 mmol aminoguanidine equivalents/kg) | [48] |

| Alginate microcapsules | Red grape skin extract | Anthocyanins: delphinidin 3-O-glucoside, cyanidin 3-O-glucoside, petunidin 3-O-glucoside, peonidin 3-O-glucoside, malvidin 3-O-glucoside Flavanols: catechin, epicatechin, procyanidin B2, procyanidin B1 Flavonols: quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin, kaempferol | The microbeads acted as pH-controlled release system for anti-glycation agents | [49] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sri Harsha, P.S.C.; Lavelli, V. Use of Grape Pomace Phenolics to Counteract Endogenous and Exogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation End-Products. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081917

Sri Harsha PSC, Lavelli V. Use of Grape Pomace Phenolics to Counteract Endogenous and Exogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation End-Products. Nutrients. 2019; 11(8):1917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081917

Chicago/Turabian StyleSri Harsha, Pedapati S. C., and Vera Lavelli. 2019. "Use of Grape Pomace Phenolics to Counteract Endogenous and Exogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation End-Products" Nutrients 11, no. 8: 1917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081917

APA StyleSri Harsha, P. S. C., & Lavelli, V. (2019). Use of Grape Pomace Phenolics to Counteract Endogenous and Exogenous Formation of Advanced Glycation End-Products. Nutrients, 11(8), 1917. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081917