Socio-Ecological Influences on Adolescent (Aged 10–17) Alcohol Use and Unhealthy Eating Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

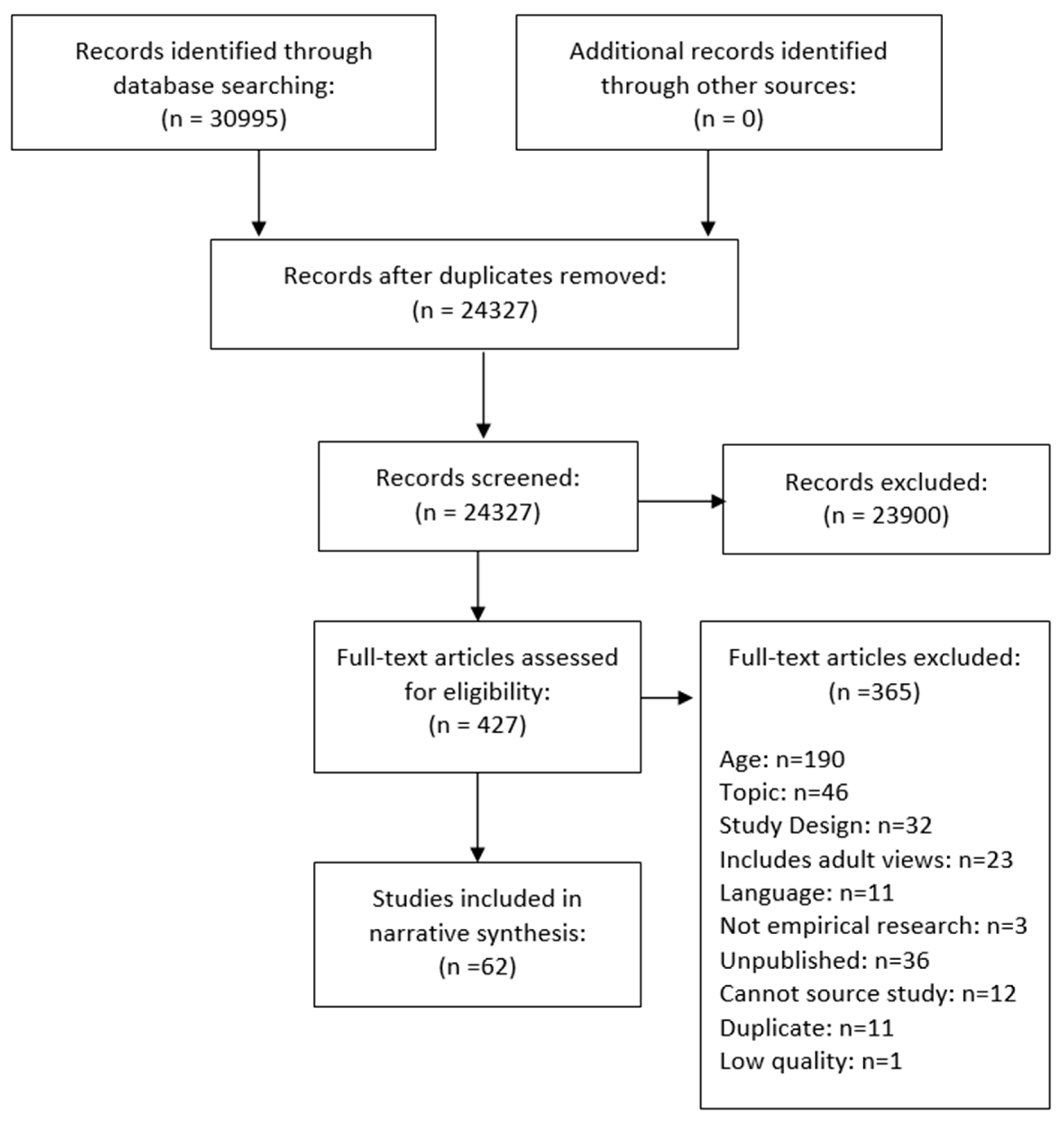

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

3.2. Alcohol and Unhealthy Food Can Be Used by Young People to Overcome Personal Problems

3.3. Young People Felt That Eating Unhealthy Food and Drinking Alcohol Are Fun Experiences

3.4. Young People Choose Food Based on Taste—This Is Not the Case for Alcohol

3.5. Exercising Control and Restraint over Alcohol and Unhealthy Food Consumption

3.6. Alcohol and Food Choices Can Be Used by Young People to Demonstrate Identity

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation. Global Health Risks. Mortality and Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risks; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, F.M.; Bloem, P.J.N.; Patton, G.C.; Ferguson, J.; Joseph, V.; Coffey, C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Mathers, C.D. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 2093–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, J.M.; Major, B.; Blodorn, A.; Miller, C.T. Weighed down by stigma: How weight-based social identity threat contributes to weight gain and poor health. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2015, 9, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, K.; Rose, H.; Boniface, S.; Deluca, P.; Coulton, S.; Alam, M.F.; Gilvarry, E.; Kaner, E.; Lynch, E.; Maconochie, I.; et al. Alcohol consumption, early-onset drinking, and health-related consequences in adolescents presenting at emergency departments in england. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, C.; Rahman, A.; Faizal, M.; Kinderman, P. Underage drinking in the UK: Changing trends, impact and interventions. A rapid evidence synthesis. Int. J. Drug Policy 2014, 25, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norström, T.; Rossow, I.; Pape, H. Social inequality in youth violence: The role of heavy episodic drinking. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018, 37, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Roe, K.; Murray, C.; Brown, G. Understanding young offenders’ experiences of drinking alcohol: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2015, 22, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccaria, F.; Rolando, S.; Ascani, P. Alcohol consumption and quality of life among young adults: A comparison among three European countries. Subst. Use Misuse 2012, 47, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiros, M.D.; Olds, T.; Buckley, J.D.; Grimshaw, P.; Brennan, L.; Walkley, J.; Hills, A.P.; Howe, P.; Coates, A.M. Health-related quality of life in obese children and adolescents. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, L.J.; Parsons, T.J.; Hill, A.J. Self-esteem and quality of life in obese children and adolescents: A systematic review. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2010, 5, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, L.J.; Bissell, P.; Copeland, R.J. ‘I just don’t want to get bullied anymore, then I can lead a normal life’; insights into life as an obese adolescent and their views on obesity treatment. Health Expect. 2016, 19, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, R.M.; Wall, M.M.; Chen, C.; Bryn Austin, S.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Experiences of weight teasing in adolescence and weight-related outcomes in adulthood: A 15-year longitudinal study. Prev. Med. 2017, 100, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C.L.; Morrison, D.S.; Batty, G.D.; Mitchell, R.J.; Davey Smith, G. Effect of body mass index and alcohol consumption on liver disease: Analysis of data from two prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2010, 340, c1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Pereira, S.M.; van Veldhoven, K.; Li, L.; Power, C. Combined early and adult life risk factor associations for mid-life obesity in a prospective birth cohort: Assessing potential public health impact. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipping, R.R.; Smith, M.; Heron, J.; Hickman, M.; Campbell, R. Multiple risk behaviour in adolescence and socio-economic status: Findings from a UK birth cohort. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 25, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, I.; Kuntsche, E. Early onset of drinking and risk of heavy drinking in young adulthood. A 13-year prospective study. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2013, 37 (Suppl. 1), 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L.; O’Loughlin, C.; Swift, W.; Romaniuk, H.; Carlin, J.; Coffey, C.; Hall, W.; Patton, G. The persistence of adolescent binge drinking into adulthood: Findings from a 15-year prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e003015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craigie, A.M.; Lake, A.A.; Kelly, S.A.; Adamson, A.J.; Mathers, J.C. Tracking of obesity-related behaviours from childhood to adulthood: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 70, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymond, B.; Dickinson, K.; Riley, M. Alcoholic beverage intake throughout the week and contribution to dietary energy intake in Australian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2592–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.E.; Richardson, G.A.; Mair, C.; Courcoulas, A.P.; King, W.C. Do associations between alcohol use and alcohol use disorder vary by weight status? Results from the national epidemiological survey on alcohol and related conditions-III. Alcohol Clin. Exp. Res. 2019, 43, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans, M.R. Short term effects of alcohol on appetite in humans. Effects of context and restrained eating. Appetite 2010, 55, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey Years 1 to 9 of the Rolling Programme (2008/2009–2016/2017): Time Trend and Income Analyses; Public Health England: London, UK, 2019.

- Public Health England. National diet and Nutrition Survey Results from Years 7 and 8 (Combined) of the Rolling Programme (2014/2015 to 2015/2016); Public Health England: London, UK, 2018.

- Kwok, A.; Dordevic, A.L.; Paton, G.; Page, M.J.; Truby, H. Effect of alcohol consumption on food energy intake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 121, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albani, V.; Bradley, J.; Wrieden, W.L.; Scott, S.; Muir, C.; Power, C.; Fitzgerald, N.; Stead, M.; Kaner, E.; Adamson, A.J. Examining associations between body mass index in 18–25 year-olds and energy intake from alcohol: Findings from the health survey for England and the Scottish health survey. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giles, E.L.; Brennan, M. Trading between healthy food, alcohol and physical activity behaviours. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.; Cummins, S.; Brown, T.; Kyle, R. Contrasting approaches to ‘doing’ family meals: A qualitative study of how parents frame children’s food preferences. Crit. Public Health 2016, 26, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacArthur, G.; Jacob, N.; Pound, P.; Hickman, M.; Campbell, R. Among friends: A qualitative exploration of the role of peers in young people’s alcohol use using bourdieu’s concepts of habitus, field and capital. Sociol. Health Illn. 2016, 39, 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.C.; Andrews, K.; Berry, N. Lost in translation: A focus group study of parents’ and adolescents’ interpretations of underage drinking and parental supply. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, W.J.; Lawton, J. Attitudes to weight and weight management in the early teenage years: A qualitative study of parental perceptions and views. Health Expect. 2014, 18, 775–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding-Singh, P.; Wang, J. Table talk: How mothers and adolescents across socioeconomic status discuss food. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 187, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clare, P.; Julie, M.P.; Miranda, C.; Lyndsey, W.; Gia, D.A.; Gayle, L.; Carole, S.; Andrew, W.; Richard, A. Engaging homeless individuals in discussion about their food experiences to optimise wellbeing: A pilot study. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 557–568. [Google Scholar]

- Østergaard, J.; Andrade, S.B. Who pre-drinks before a night out and why? Socioeconomic status and motives behind young people’s pre-drinking in the United Kingdom. J. Subst. Use 2014, 19, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Muirhead, C.; Shucksmith, J.; Tyrrell, R.; Kaner, E. Does industry-driven alcohol marketing influence adolescent drinking behaviour? A systematic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017, 52, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCreanor, T.; Barnes, H.; Kaiwai, H.; Borell, S.; Gregory, A. Creating intoxigenic environments: Marketing alcohol to young people in Aotearoa New Zealand. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.; Wiers, R.W.; Hommel, B.; Ridderinkhof, K.R.; de Wit, S. An associative account of how the obesogenic environment biases adolescents’ food choices. Appetite 2016, 96, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrrell, R.L.; Greenhalgh, F.; Hodgson, S.; Wills, W.J.; Mathers, J.C.; Adamson, A.J.; Lake, A.A. Food environments of young people: Linking individual behaviour to environmental context. J. Public Health 2016, 39, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, M.; McDermott, L.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Adamson, A. Why healthy eating is bad for young people’s health: Identity, belonging and food. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, W.J.; Backett-Milburn, K.; Gregory, S.; Lawton, J. ‘If the food looks dodgy I dinnae eat it’: Teenagers’ accounts of food and eating practices in socio-economically disadvantaged families. Sociol. Res. Online 2008, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, M. Seeking the pleasure zone: Understanding young adult’s intoxication culture. Australas. Mark. J. 2011, 19, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ander, B.; Abrahamsson, A.; Bergnehr, D. ‘It is ok to be drunk, but not too drunk’: Party socialising, drinking ideals, and learning trajectories in Swedish adolescent discourse on alcohol use. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, H.; Smith, E.; Neary, J.; Wright, C. ‘Now I care’: A qualitative study of how overweight adolescents managed their weight in the transition to adulthood. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savell, E.; Fooks, G.; Gilmore, A.B. How does the alcohol industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. Addiction 2016, 111, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munt, A.E.; Partridge, S.R.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The barriers and enablers of healthy eating among young adults: A missing piece of the obesity puzzle: A scoping review. Obes. Rev. 2016, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, S.; Reilly, J.; Giles, E.L.; Hillier-Brown, F.; Ells, L.; Kaner, E.; Adamson, A. Socio-ecological influences on adolescent (aged 10–17) alcohol use and linked unhealthy eating behaviours: Protocol for a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond pico: The spider tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.P.; Hart, R.I.; Watson, R.M.; Rapley, T. Qualitative synthesis in practice: Some pragmatics of meta-ethnography. Qual. Res. 2015, 15, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.; Pound, P.; Pope, C.; Britten, N.; Pill, R.; Morgan, M.; Donovan, J. Evaluating meta-ethnography: A synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, S.; Sousa, S.; Ramos, E.; Dias, S.; Barros, H. Alcohol use among 13-year-old adolescents: Associated factors and perceptions. Public Health 2011, 125, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrilli, E.; Beccaria, F.; Prina, F.; Rolando, S. Images of alcohol among Italian adolescents. Understanding their point of view. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2014, 21, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samardzik, S.; Bujsic, G.; Kozul, K.; Tadijan, D. Drinking in adolescents—Qualitative analysis. Coll. Antropol. 2011, 35, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Katainen, A.; Lehto, A.-S.; Maunu, A. Adolescents’ sense-making of alcohol-related risks: The role of drinking situations and social settings. Health 2015, 19, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonsson, L.; Larsson, C.; Berg, C.; Korp, P.; Lindgren, E.-C. What undermines healthy habits with regard to physical activity and food? Voices of adolescents in a disadvantaged community. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2017, 12, 1333901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, A.W.; Lovato, C.Y.; Barr, S.I.; Hanning, R.M.; Mâsse, L.C. Experiences of overweight/obese adolescents in navigating their home food environment. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3278–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.; Jackson, L.A. Meanings that youth associate with healthy and unhealthy food. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2009, 70, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.L. Negotiating popular obesity discourses in adolescence. Food Cult. Soc. 2011, 14, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.A.; McKay, M.T. Perspectives on adolescent alcohol use and consideration of future consequences: Results from a qualitative study. Child Care Pract. 2017, 23, 104–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katainen, A.; Rolando, S. Adolescents’ understandings of binge drinking in southern and northern European contexts—Cultural variations of ‘controlled loss of control’. J. Youth Stud. 2015, 18, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Shucksmith, J.; Baker, R.; Kaner, E. ‘Hidden habitus’: A qualitative study of socio-ecological influences on drinking practices and social identity in mid-adolescence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ander, B.; Abrahamsson, A.; Gerdner, A. Changing arenas of underage adolescent binge drinking in Swedish small towns. Nord. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2015, 32, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, J.L.; Hsiao, Y.-C.; Kasat-Shors, M.; Murray, L.; Nguyen, N.K.; Richards, A.K.; Gittelsohn, J. Formative research for a healthy diet intervention among inner-city adolescents: The importance of family, school and neighborhood environment. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2009, 48, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, S.; Lam, W.W.T.; Sham, J.T.L.; Lam, T.-H. Learning to drink: How Chinese adolescents make decisions about the consumption (or not) of alcohol. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acier, D.; Kindelberger, C.; Chevalier, C.; Guibert, E. “I always stop before I get sick”: A qualitative study on French adolescents alcohol use. J. Subst. Use 2015, 20, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Exel, J.; Koolman, X.; de Graaf, G.; Brouwer, W. Overweight and Obesity in Dutch Adolescents: Associations with Health Lifestyle, Personality, Social Context and Future Consequences: Methods and Tables. Report 06.82; Institute for Medical Technology Assessment: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Boutrup Jensen, B.; Pedersen, S. An exploration of adolescent snacking conventions and dilemmas. Young Consum. 2010, 11, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.; Tse, T.; Tam, D.; Huang, A. Perception of healthy and unhealthy food among Chinese adolescents. Young Consum. 2016, 17, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensaff, H.; Coan, S.; Sahota, P.; Braybrook, D.; Akter, H.; McLeod, H. Adolescents’ food choice and the place of plant-based foods. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4619–4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavaravarapu, S.M.; Rao, K.M.; Nagalla, B.; Avula, L. Assessing differences in risk perceptions about obesity among “normal-weight” and “overweight” adolescents—A qualitative study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Breiting, S.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. Effect of organic school meals to promote healthy diet in 11–13 year old children. A mixed methods study in four Danish public schools. Appetite 2012, 59, 866–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunsberger, M.; McGinnis, P.; Smith, J.; Beamer, B.A.; O’Malley, J. Calorie labeling in a rural middle school influences food selection: Findings from community-based participatory research. J. Obes. 2015, 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protudjer, J.L.P.; Marchessault, G.; Kozyrskyj, A.L.; Becker, A.B. Children’s perceptions of healthful eating and physical activity. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2010, 71, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhshanderou, S.; Ramezankhani, A.; Mehrabi, Y.; Ghaffari, M. Determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among tehranian adolescents: A qualitative research. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 19, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ridder, M.A.; Heuvelmans, M.A.; Visscher, T.L.; Seidell, J.C.; Renders, C.M. We are healthy so we can behave unhealthily: A qualitative study of the health behaviour of Dutch lower vocational students. Health Educ. 2010, 110, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.C.D.A.; Frazão, I.D.S.; Osório, M.M.; Vasconcelos, M.G.L.D. Perception of adolescents on healthy eating. Ciencia Saude Coletiva 2015, 20, 3299–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, C.; Doherty, G.; Barnett, J.; Muldoon, O.T.; Trew, K. Adoelscents’ views of food and eating: Identifying barriers to healthy eating. J. Adolesc. 2007, 30, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, L.D.; McNaughton, S.A.; Crawford, D.; Ball, K. Nutrition promotion approaches preferred by Australian adolescents attending schools in disadvantaged neighbourhoods: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2015, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakken, S.A.; Sandøy, T.A.; Sandberg, S. Social identity and alcohol in young adolescence: The perceived difference between youthful and adult drinking. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 20, 1380–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnson, P. ‘You just get blocked’. Teenage drinkers: Reckless rebellion or responsible reproduction? Child. Soc. 2011, 25, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.L.; Martin, J.; Foxcroft, D.R. Young people talking about alcohol: Focus groups exploring constructs in the prototype willingness model. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2013, 20, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romo-Avilés, N.; Marcos-Marcos, J.; Tarragona-Camacho, A.; Gil-García, E.; Marquina-Márquez, A. “I like to be different from how I normally am”: Heavy alcohol consumption among female Spanish adolescents and the unsettling of traditional gender norms. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2018, 25, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parder, M.-L. What about just saying “no”? Situational abstinence from alcohol at parties among 13–15 year olds. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2018, 25, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunnay, B.; Ward, P.; Borlagdan, J. The practise and practice of bourdieu: The application of social theory to youth alcohol research. Int. J. Drug Policy 2011, 22, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioannou, S. ‘Eating beans… that is a “no-no” for our times’: Young Cypriots’ consumer meanings of ‘healthy’and ‘fast’food. Health Educ. J. 2009, 68, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronto, R.; Ball, L.; Pendergast, D.; Harris, N. Adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours. Appetite 2016, 107, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashcraft, P.F. Explanatory models of obesity of inner-city African-American adolescent males. J. Pediatric Nurs. 2013, 28, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witmer, L.; Bocarro, J.N.; Henderson, K. Adolescent girls’ perception of health within a leisure context. J. Leis. Res. 2011, 43, 334–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, S.; Skjælaaen, Ø. “Shoes on your hands”: Perceptions of alcohol among young adolescents in Norway. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy 2018, 25, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, K.; Schmidtke, D.J.; Dietrich, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. “Everyone was wasted”! Insights from adolescents’ alcohol experience narratives. Young Consum. 2016, 17, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, M.H.; Curtis, T.; Christensen, P.H.; Grønbæk, M. Harm minimization among teenage drinkers: Findings from an ethnographic study on teenage alcohol use in a rural Danish community. Addiction 2007, 102, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, N.J.S.; Bakke, S.L.; Dalum, P. “No alcohol, no party”: An explorative study of young Danish moderate drinkers. Scand. J. Public Health 2012, 40, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. ‘You think you’re a rebel on a big bottle’: Teenage drinking, peers and performance authenticity. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 16, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, E.M.; Suárez, D.E.; Lema, M.; Londoño, A. How adolescents learn about risk perception and behavior in regards to alcohol use in light of social learning theory: A qualitative study in Bogota, Colombia. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2015, 27, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvinen, M.; Østergaard, J. Governing adolescent drinking. Youth Soc. 2009, 40, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelkrem, K.; Lien, N.; Wandel, M. Perceptions of slimming and healthiness among Norwegian adolescent girls. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmigin, I.; Griffin, C.; Mistral, W.; Bengry-Howell, A.; Weale, L.; Hackley, C. Re-framing ‘binge drinking’ as calculated hedonism: Empirical evidence from the UK. Int. J. Drug Policy 2008, 19, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnell, D.; Kidger, J.; Elvidge, H. Adolescent mental health in crisis. BMJ 2018, 361, K2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, A.D.; Leadbeater, B.J. The longitudinal effects of peer victimization on physical health from adolescence to young adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, D.; Caldwell, P.H.; Go, H. Impact of social media on the health of children and young people. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2015, 51, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugge, A.B. Food advertising towards children and young people in Norway. Appetite 2016, 98, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, B.; Kelly, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Baur, L. Young adults: Beloved by food and drink marketers and forgotten by public health? Health Promot. Int. 2015, 31, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Baker, R.; Shucksmith, J.; Kaner, E. Autonomy, special offers and routines: A Q methodological study of industry-driven marketing influences on young people’s drinking behaviour. Addiction 2014, 109, 1833–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visram, S.; Crossley, S.J.; Cheetham, M.; Lake, A. Children and young people’s perceptions of energy drinks: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visram, S.; Cheetham, M.; Riby, D.M.; Crossley, S.J.; Lake, A.A. Consumption of energy drinks by children and young people: A rapid review examining evidence of physical effects and consumer attitudes. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitt, H.; Thomas, S.L.; Bestman, A. Initiation, influence, and impact: Adolescents and parents discuss the marketing of gambling products during Australian sporting matches. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghi, F.; Liga, F.; Baumgartner, E.; Baiocco, R. Time perspective and psychosocial positive functioning among Italian adolescents who binge eat and drink. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdonald, L.; Olsen, J.R.; Shortt, N.K.; Ellaway, A. Do ‘environmental bads’ such as alcohol, fast food, tobacco, and gambling outlets cluster and co-locate in more deprived areas in Glasgow city, Scotland? Health Place 2018, 51, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katikireddi, S.V.; Whitley, E.; Lewsey, J.; Gray, L.; Leyland, A.H. Socioeconomic status as an effect modifier of alcohol consumption and harm: Analysis of linked cohort data. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e267–e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scott, S.; Elamin, W.; Giles, E.L.; Hillier-Brown, F.; Byrnes, K.; Connor, N.; Newbury-Birch, D.; Ells, L. Socio-Ecological Influences on Adolescent (Aged 10–17) Alcohol Use and Unhealthy Eating Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081914

Scott S, Elamin W, Giles EL, Hillier-Brown F, Byrnes K, Connor N, Newbury-Birch D, Ells L. Socio-Ecological Influences on Adolescent (Aged 10–17) Alcohol Use and Unhealthy Eating Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Nutrients. 2019; 11(8):1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081914

Chicago/Turabian StyleScott, Stephanie, Wafa Elamin, Emma L. Giles, Frances Hillier-Brown, Kate Byrnes, Natalie Connor, Dorothy Newbury-Birch, and Louisa Ells. 2019. "Socio-Ecological Influences on Adolescent (Aged 10–17) Alcohol Use and Unhealthy Eating Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies" Nutrients 11, no. 8: 1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081914

APA StyleScott, S., Elamin, W., Giles, E. L., Hillier-Brown, F., Byrnes, K., Connor, N., Newbury-Birch, D., & Ells, L. (2019). Socio-Ecological Influences on Adolescent (Aged 10–17) Alcohol Use and Unhealthy Eating Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Nutrients, 11(8), 1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081914