Trends and Correlates of Overweight among Pre-School Age Children, Adolescent Girls, and Adult Women in South Asia: An Analysis of Data from Twelve National Surveys in Six Countries over Twenty Years

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Datasets

2.2. Analytic Samples

2.3. Child Variables

2.4. Adolescents’ and Women’s Variables

2.5. Household and Environmental Variables

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

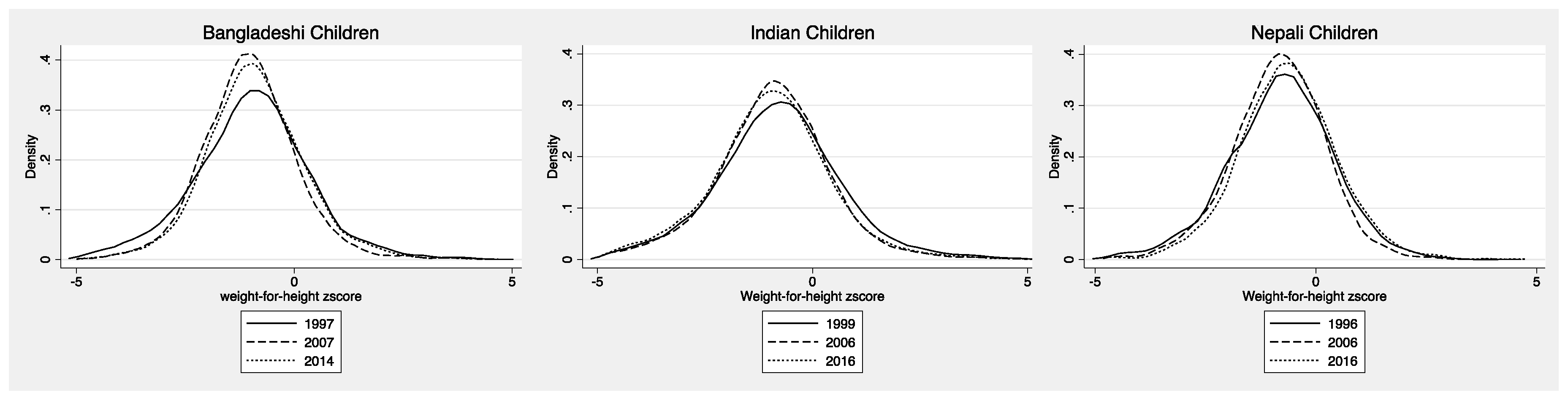

3.1. Pre-School Aged Children

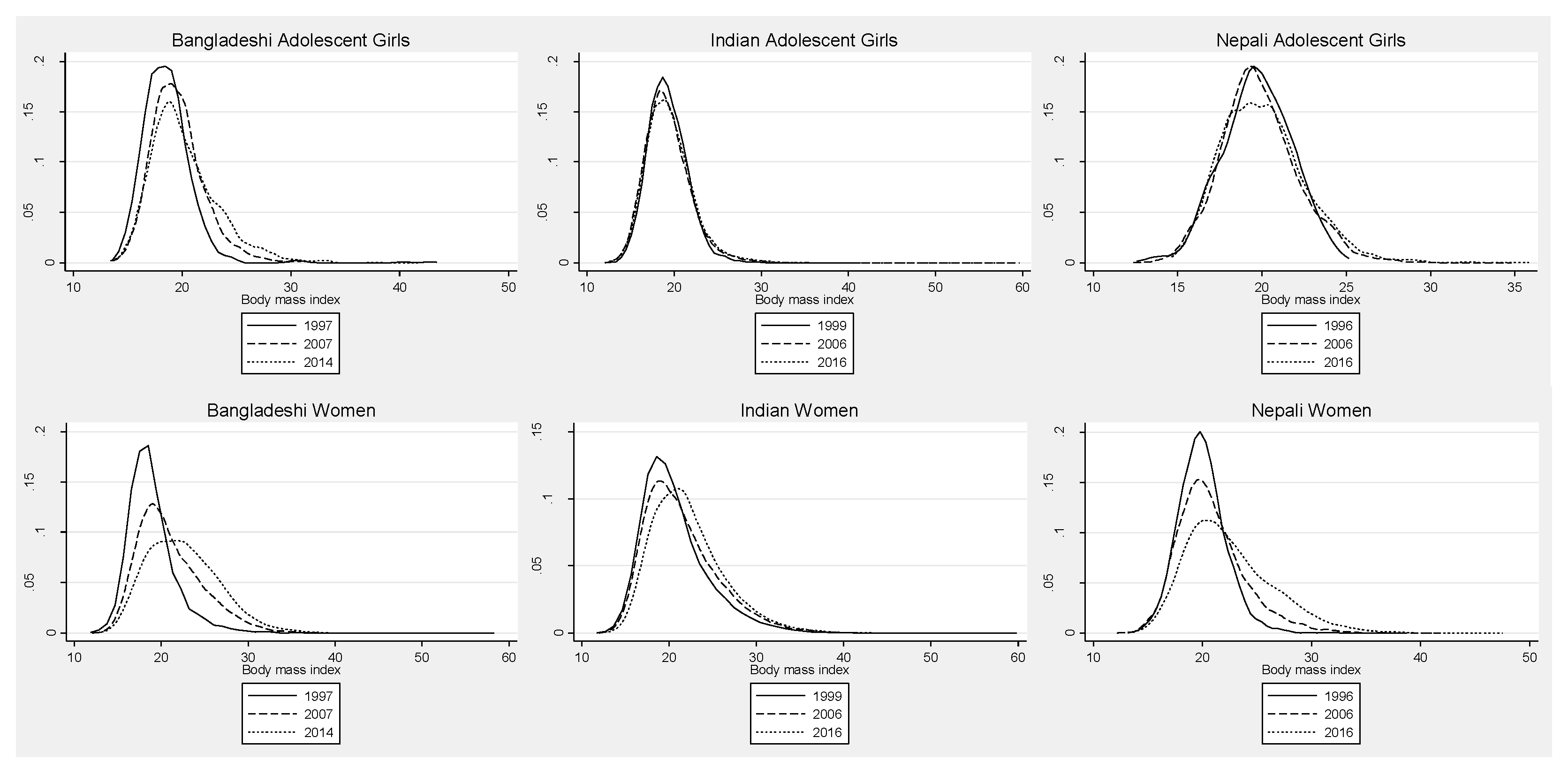

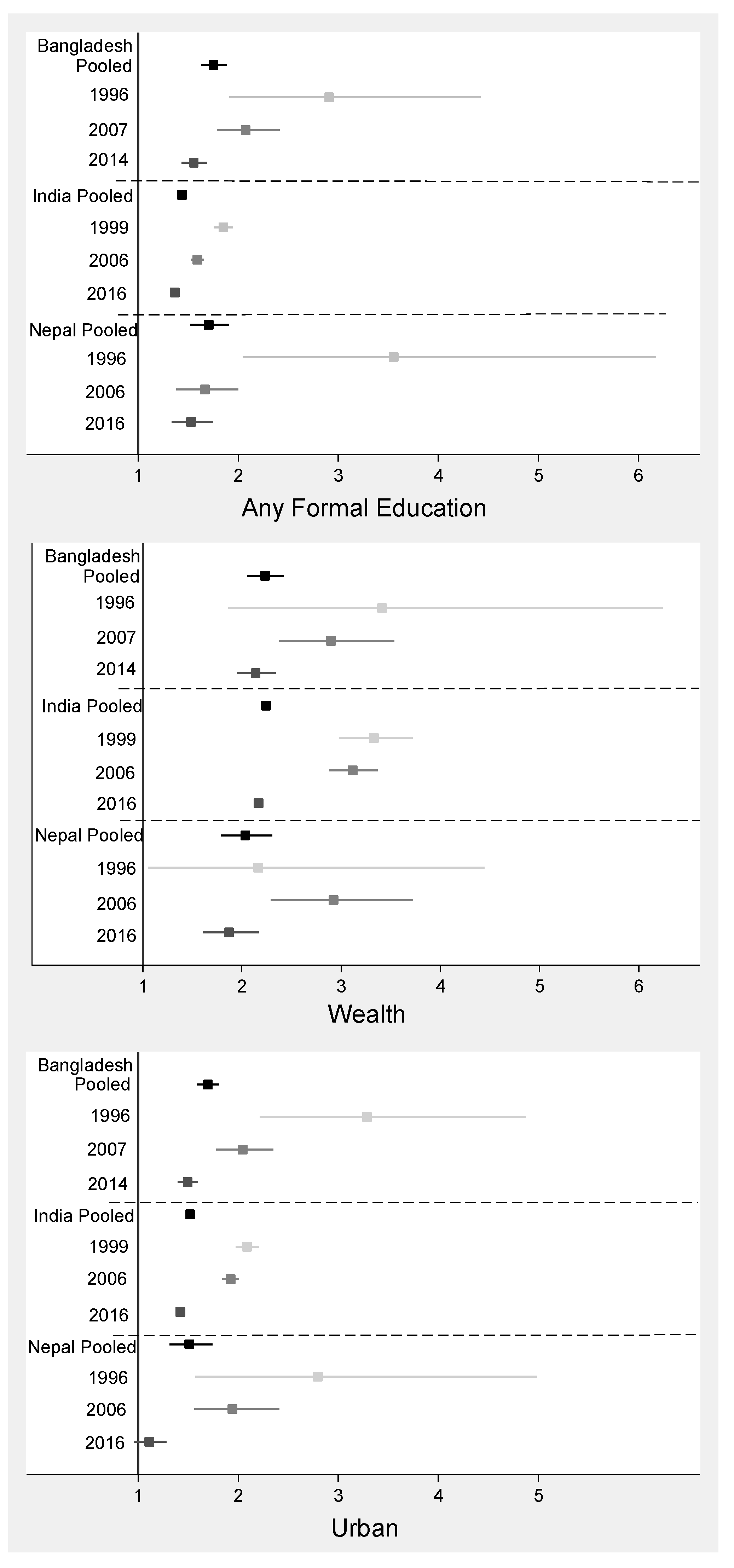

3.2. Adolescent Girls

3.3. Adult Women

4. Discussion

4.1. Pre-School Aged Children

4.2. Adolescent Girls

4.3. Adult Women

4.4. Limitations and Strengths

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Abera, S.F.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 384, 766–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Slining, M.M. New dynamics in global obesity facing low- and middle-income countries. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF; World Health Organization; World Bank Group. Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. In Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition, 2019 ed.; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Galea, S.; El-Sayed, A.M.; Scarborough, P. Ethnic inequalities in obesity among children and adults in the UK: A systematic review of the literature. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 516–534. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, M.E.; Mannan, M.; Long, K.Z.; Mamun, A.A. Economic burden of underweight and overweight among adults in the Asia-Pacific region: A systematic review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2016, 21, 458–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly, J.J.; Kelly, J. Long-term impact of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence on morbidity and premature mortality in adulthood: Systematic review. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mistry, S.; Puthussery, S. Risk factors of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence in South Asian countries: A systematic review of the evidence. Public Health 2015, 129, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Goel, K.; Shah, P.; Misra, A. Childhood Obesity in Developing Countries: Epidemiology, Determinants, and Prevention. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Silva, A.P.; De Silva, S.H.P.; Haniffa, R.; Liyanage, I.K.; Jayasinghe, K.S.A.; Katulanda, P.; Wijeratne, C.N.; Wijeratne, S.; Rajapakse, L.C. A cross sectional survey on social, cultural and economic determinants of obesity in a low middle income setting. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones-Smith, J.C.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Siddiqi, A.; Popkin, B.M. Is the burden of overweight shifting to the poor across the globe? Time trends among women in 39 low- and middle-income countries (1991–2008). Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 1114–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Conde, W.L.; Popkin, B.M. The Burden of Disease from Undernutrition and Overnutrition in Countries Undergoing Rapid Nutrition Transition: A View from Brazil. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 433–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global nutrition transition and the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Popkin, B. The nutrition transition: Worldwide obesity dynamics and their determinants. Int. J. Obes. 2004, 28, S2–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones-Smith, J.C.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Siddiqi, A.; Popkin, B.M. Emerging disparities in overweight by educational attainment in Chinese adults (1989–2006). Int. J. Obes. 2012, 36, 866–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajit, P.; Aryal, R.H.; Regmi, G.; Ban, B.; Govindasamy, P. Nepal Family Health Survey 1996; Ministry of Health/Nepal; New ERA/Nepal; Macro International: Kathmandu, Nepal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS); ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16: India; IIPS: Mumbai, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS); Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2), 1998–99: India; IIPS: Mumbai, India, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS); Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India; IIPS: Mumbai, India, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Family (MOHF); ICF Macro. Maldives Demographic and Health Survey 2009; MOHF; ICF Macro: Calverton, MD, USA, 2010.

- Ministry of Health and Population (MOHP); New ERA; Macro International. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2006; Ministry of Health and Population; New ERA; Macro International: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2007.

- Ministry of Health Nepal; New ERA; ICF. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2016; Ministry of Health Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017.

- Ministry of Public Health; UNICEF; Aga Khan University. National Nutrition Survey Afghanistan 2013; Ministry of Public Health: Kabul, Afghanistan, 2014.

- Mitra, S.N.; Al-Sabir, A.; Cross, A.R.; Jamil, K. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey, 1996–1997; National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT); Mitra and Associates: Dhaka, Bangladesh; Macro International Inc.: Calverton, MD, USA, 1997.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT); Mitra and Associates; ICF International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2014; NIPORT; Mitra and Associates: Dhaka, Bangladesh; ICF International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016.

- National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT); Mitra and Associates; Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007; NIPORT; Mitra and Associates: Dhaka, Bangladesh; Macro International: Calverton, MD, USA, 2019.

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS); ICF International. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–13; NIPS: Islamabad, Pakistan; ICF International: Calverton, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, K.L.; Aguayo, V.M.; Webb, P. Factors associated with wasting among children under five years old in South Asia: Implications for action. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, J. ZSCORE06: Stata Command for the Calculation of Anthropometric Z-Scores Using the 2006 WHO Child Growth Standards. 2011. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s457279.htm (accessed on 18 December 2017).

- World Health Organization. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices Part 1: Definition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices Part II: Measurement; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet 2004, 363, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, T.J.; Bellizzi, M.C.; Flegal, K.M.; Dietz, W.H. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ 2000, 320, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICF. Demographic and Health Surveys Standard Recode Manual for DHS7; The Demographic and Health Surveys Program; ICF: Rockville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein, S.O.; Johnson, K. The DHS Wealth Index; DHS Comparative Reports No. 6; ORC Macro: Calverton, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Deddens, J.A.; Petersen, M.R. Approaches for estimating prevalence ratios. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 65, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.Y. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 159, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguyao, V.; Paintal, K. Nutrition in adolescent girls in South Asia. BMJ 2017, 357, j1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, M.U.; Zaman, S.; Ahmed, T. Risk factors associated with overweight and obesity among urban school children and adolescents in Bangladesh: A case-control study. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mahabalaraju, D.K.; Anuroopa, M.S. Prevalence of obesity and its influencing factor among affluent school children of Davangere city. Indian J. Community Med. 2007, 32, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Pant, B.; Chopra, H.; Tiwari, R. Obesity among adolescents of affluent public schools in Meerut. Indian J. Public Health 2010, 54, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Oestergaard, M.Z.; Chou, D.; Moller, A.-B.; Narwal, R.; Adler, A.; Garcia, C.V.; Rohde, S.; Say, L.; et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012, 379, 2162–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, P.M. Editorial: Obesity and pregnancy—The propagation of a viscous cycle? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 3505–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.D.; Han, Z.; Mulla, S.; Beyene, J. Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2010, 341, c3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, A.T.; Cleves, M.A.; Casey, P.H.; Cradock, M.M.; Anand, K.J.S. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2002, 288, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Cutfield, W.; Hofman, P.; Hanson, M.A. The fetal, neonatal, and infant environments—the long-term consequences for disease risk. Early Hum. Dev. 2005, 81, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.; Regan, F.; Harris, M.; Robinson, E.; Jackson, W.; Cutfield, W. The metabolic consequences of prematurity. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2004, 14, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.L.; Regan, F.; Jackson, W.E.; Jefferies, C.; Knight, D.B.; Robinson, E.M.; Cutfield, W.S. Premature Birth and Later Insulin Resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 2179–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.; Reilly, J.J. Breastfeeding and lowering the risk of childhood obesity. Lancet 2002, 359, 2003–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, M.W.; McDade, T.W. Breastfeeding as Obesity Prevention in the United States: A Sibling Difference Model. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2010, 22, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, K.M.; Cross, M.B.; Hughes, S.O. A Systematic Review of Responsive Feeding and Child Obesity in High-Income Countries. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschann, J.M.; Martinez, S.M.; Penilla, C.; Gregorich, S.E.; Pasch, L.A.; De Groat, C.L.; Flores, E.; Deardorff, J.; Greenspan, L.C.; Butte, N.F. Parental feeding practices and child weight status in Mexican American families: A longitudinal analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, R.L.; Mobley, A.R. Parenting styles, feeding styles, and their influence on child obesogenic behaviors and body weight. A review. Appetite 2013, 71, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaacks, L.M.; Slining, M.M.; Popkin, B.M. Recent trends in the prevalence of under- and overweight among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Pediatr. Obes. 2015, 10, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, M.; Sununtnasuk, C.; Ahmed, A.; Leroy, J.L. Understanding the determinants of adolescent nutrition in Bangladesh. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1416, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Pons, A.; Tur, J.A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adolescents: A systematic review. ISRN Obes. 2013, 2013, 392747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moura, E.C.; Conde, W.L.; Popkin, B.M. Socioeconomic status and obesity in adult populations of developing countries: A review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004, 82, 940–946. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S.V.; Perkins, J.M.; Özaltin, E.; Davey Smith, G. Weight of nations: A socioeconomic analysis of women in low- to middle-income countries. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 93, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Hu, F.B.; Bowen, L.; Bharathi, A.V.; Vaz, M.; Prabhakaran, D.; Reddy, K.S.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Smith, G.D.; Kinra, S.; et al. Dietary patterns in India and their association with obesity and central obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3031–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.; Krishnan, A. Changing patterns of diet, physical activity and obesity among urban, rural and slum populations in north India. Obes. Rev. 2008, 9, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R.; Sutherland, J.; Dangour, A.D.; Shankar, B.; Webb, P. Global dietary quality, undernutrition and non-communicable disease: A longitudinal modelling study. BMJ Open 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; De Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, T.; Sonntag, D.; Konnopka, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.; König, H.-H. Economic costs of overweight and obesity. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 27, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withrow, D.; Alter, D.A. The economic burden of obesity worldwide: A systematic review of the direct costs of obesity. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA65.6. Comprehensive implementation plan on maternal, infant and young child nutrition. In Proceedings of the Sixty-Fifth World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, 21–26 May 2012; Resolutions and Decisions, Annexes. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Global Monitoring Framework: Indicator Definitions and Specifications; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/ncd-tools/definition-targets/en/ (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, A.I.; Ponce, N.A.; Crespi, C.M.; Frank, J.; Nandi, A.; Heymann, J. Economic policy and the double burden of malnutrition: Cross-national longitudinal analysis of minimum wage and women’s underweight and obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Afghanistan | Bangladesh | India | Maldives | Nepal | Pakistan | Recent Pooled 3 | |||||||

| 2013 | 1997 | 2007 | 2014 | 1999 | 2006 | 2016 | 2009 | 1996 | 2006 | 2016 | 2013 | ||

| Pre-school aged children | |||||||||||||

| n | 10,958 | 4394 | 5022 | 6632 | 22,609 | 37,881 | 206,463 | 2226 | 3321 | 4809 | 2218 | 2624 | 231,121 |

| Age (months) | |||||||||||||

| <6 months | 16.9 | 10.8 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 19.2 | 9.2 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 17.7 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 11.2 | 9.5 |

| 6–12 months | 15.7 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 14.1 | 20.8 | 12.5 | 12.7 | 14.7 | 22.7 | 11.7 | 13 | 12.2 | 12.8 |

| 13–24 months | 19.5 | 20.1 | 21.3 | 21.5 | 32.3 | 19.1 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 33.8 | 19.1 | 20.7 | 17.4 | 19.4 |

| 25–36 months | 18.1 | 18.7 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 27.7 | 19.5 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 25.9 | 20.5 | 18.6 | 20 | 19.6 |

| 37–48 months | 17.4 | 20 | 18.8 | 19.2 | 0 | 20.3 | 20.9 | 18.8 | 0 | 20.1 | 19.9 | 19.4 | 20.6 |

| 49–59 months | 12.4 | 17.6 | 18.2 | 17 | 0 | 19.4 | 18.5 | 16.5 | 0 | 18.5 | 18 | 19.8 | 18.1 |

| Female | 48.1 | 50.3 | 50.2 | 47.7 | 47.8 | 47.1 | 47.4 | 49.9 | 48 | 48 | 47.3 | 48.8 | 47.7 |

| Urban | 23.3 | 9.5 | 21.6 | 25.7 | 23.8 | 25.1 | 28.4 | 31 | 5.9 | 12.4 | 53.3 | 31 | 24.3 |

| Weight-for-height z-score [mean ± SD] | −0.27 ± 1.42 | −0.99 ± 1.33 | −1.04 ± 1.08 | −0.88 ± 1.16 | −0.88 ± 1.44 | −1.01± 1.29 | −1.02 ± 1.37 | −0.44 ± 1.41 | −0.80 ± 1.19 | −0.84 ± 1.07 | −0.65 ± 1.14 | −0.52 ± 1.30 | −0.91 ± 1.40 |

| Height-for-age z-score [mean ± SD] | −1.50 ± 1.76 | −2.31 ± 1.53 | −1.73 ± 1.35 | −1.52 ± 1.31 | −1.94 ± 1.77 | −1.82 ± 1.66 | −1.45 ± 1.67 | −0.89 ± 1.39 | −2.15 ± 1.40 | −1.89 ± 1.34 | −1.51 ± 1.34 | −1.75 ± 1.72 | − 1.46 ± 1.68 |

| Stunting (HAZ < −2) | 38.4 | 59.6 | 42.3 | 35.3 | 49.7 | 46.9 | 37.6 | 17.9 | 55.8 | 48.1 | 35.4 | 44.5 | 37.6 |

| Wasting (WHZ < −2) | 9.5 | 20.7 | 17.4 | 14.3 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 21.1 | 10.6 | 15 | 12.7 | 10.2 | 10.9 | 19.6 |

| Overweight (WHZ > 2) | 5.3 | 1.9 | 1 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 5.8 | 1 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Afghanistan | Bangladesh | India | Maldives | Nepal | Pakistan | Recent Pooled 3 | |||||||

| 2013 | 1997 | 2007 | 2014 | 1999 | 2006 | 2016 | 2009 | 1996 | 2006 | 2016 | 2013 | ||

| Adolescent girls (15–19 years old) | |||||||||||||

| n | 2231 | 668 | 1096 | 1667 | 5119 | 21,818 | 118,602 | 75 | 336 | 2282 | 1251 | 164 | 123,990 |

| Age (years) [mean ± SD] | 16.8 ± 1.4 | 17.2 ± 1.3 | 17.5 ± 1.3 | 17.5 ± 1.3 | 17.6 ± 1.3 | 16.9 ± 1.4 | 16.9 ± 1.4 | 18.7 ± 0.5 | 18.1 ± 1.0 | 16.9 ± 1.4 | 16.9 ± 1.4 | 18.1 ± 0.8 | 16.9 ± 1.4 |

| Urban | 30.3 | 8.1 | 17.4 | 26.5 | 14.3 | 30.1 | 30.3 | 24.5 | 5.3 | 14.6 | 63.5 | 22.8 | 27 |

| Married | 20.7 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 23.6 | 12.6 | 100 | 100 | 27.8 | 23.4 | 100 | 12.8 |

| Number of times given birth [mean ± SD] | 1.5 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.8 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| No education | 45.4 | 44.6 | 9.6 | 4.9 | 53.1 | 20.1 | 6.5 | 0 | 66.5 | 19.8 | 5.8 | 49.7 | 7.5 |

| Short stature (<145 cm) | 9.6 | 18.1 | 16.6 | 13 | 14.9 | 11.7 | 12.7 | 5.5 | 13.9 | 14.41 | 10.3 | 8.8 | 12.6 |

| Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) [mean ± SD] | 21.0 ± 3.2 | 18.6 ± 2.4 | 19.6 ± 2.4 | 20.2 ± 3.2 | 19.1 ± 2.3 | 19.0 ± 2.5 | 19.4 ± 3.0 | 21.9 ± 4.6 | 19.6 ± 2.1 | 19.9 ± 2.3 | 20.0 ± 2.6 | 20.6 ± 2.8 | 19.5 ± 2.9 |

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 21.6 | 50.3 | 34.4 | 30.9 | 42.2 | 46.6 | 41.8 | 23.4 | 29.9 | 26.2 | 30 | 22.5 | 38.9 |

| Overweight based on cut-off ≥23.0 kg/m2 | 20.4 | 2.3 | 8.2 | 17 | 4.5 | 6.1 | 9.5 | 37.5 | 5.2 | 10.1 | 12.3 | 17 | 9.5 |

| Overweight based on cut-off ≥25.0 kg/m2 | 9.5 | 0.7 | 3 | 7.3 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 4.25 | 24.5 | 0 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 3.9 |

| Obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) | 1.9 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Based on IOTF standards | |||||||||||||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 16.7 | 46.6 | 30.8 | 26.7 | 38.1 | 39.1 | 35.1 | 23.4 | 28.8 | 18.8 | 23.8 | 22 | 32.4 |

| Overweight based on cut-off ≥23.0 kg/m2 | 25.3 | 2.5 | 9.3 | 19.2 | 5.5 | 7.5 | 11.2 | 37.5 | 6.1 | 12.7 | 14.7 | 18.2 | 11.6 |

| Overweight based on cut-off ≥25.0 kg/m2 | 10.4 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 8.2 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 4.9 | 24.5 | 0 | 3 | 4.4 | 7.1 | 4.6 |

| Obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) | 2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 1.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 |

| Afghanistan | Bangladesh | India | Maldives | Nepal | Pakistan | Recent Pooled 3 | |||||||

| 2013 | 1997 | 2007 | 2014 | 1999 | 2006 | 2016 | 2009 | 1996 | 2006 | 2016 | 2013 | ||

| Adult women (20–49 years old) | |||||||||||||

| n | 9520 | 3377 | 9031 | 14,957 | 72,494 | 91,257 | 536,554 | 5138 | 2972 | 7834 | 4914 | 3969 | 575,052 |

| Age (year) | 31.0 ± 7.6 | 27.5 ± 5.9 | 32.7 ± 8.4 | 32.9 ± 8.3 | 32.8 ± 8.1 | 32.5 ± 8.2 | 33.1 ± 8.5 | 33.4 ± 8.0 | 28.0 ± 6.1 | 32.6 ± 8.5 | 32.7 ± 8.3 | 33.9 ± 8.3 | 33.0 ± 8.4 |

| Urban | 27.23 | 10.35 | 23.51 | 28.63 | 27.65 | 32.97 | 35.22 | 32.14 | 6.1 | 16.08 | 63.02 | 34.01 | 30 |

| Number of times given birth [mean ± SD] | 4.7 ± 2.5 | 3.6 ± 2.2 | 3.2 ± 2.0 | 2.8 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 2.1 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 2.3 | 3.7 ± 2.2 | 3.2 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 2.7 | 2.4 ± 1.8 |

| No education | 80.4 | 56.4 | 38.1 | 28 | 52.5 | 45.3 | 32.22 | 26.2 | 81.1 | 62.6 | 40.82 | 57.4 | 33.96 |

| Short stature (<145 cm) | 3.7 | 17.1 | 15 | 12.7 | 13 | 11.4 | 10.81 | 12.6 | 15 | 14.1 | 10.92 | 5 | 10.21 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) [mean ± SD] | 23.5 ± 4.5 | 18.9 ± 2.9 | 20.8 ± 3.6 | 22.5 ± 4.2 | 20.4 ± 3.8 | 20.8 ± 4.1 | 22.4 ± 4.5 | 24.9 ± 4.7 | 19.8 ± 2.2 | 20.8 ± 3.2 | 22.7 ± 4.2 | 24.4 ± 5.6 | 22.3 ± 4.3 |

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 9.1 | 51.6 | 28.9 | 17.2 | 35.7 | 32.7 | 18.81 | 7.2 | 27.5 | 23.7 | 13.98 | 13.4 | 18.19 |

| Overweight based on cut-off ≥23.0 kg/m2 | 46.1 | 7.2 | 23.6 | 41.6 | 19.8 | 24.9 | 38.34 | 63.8 | 7.5 | 20.6 | 40.99 | 55.8 | 36.64 |

| Overweight based on cut-off ≥25.0 kg/m2 | 29.3 | 3.2 | 12.9 | 25.6 | 11.4 | 15.1 | 24.09 | 45.8 | 1.9 | 10.4 | 26.81 | 41.2 | 22.24 |

| Obese (≥30.0 kg/m2) | 8.7 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 6.04 | 13.2 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 6.26 | 15.4 | 5.25 |

| Overweight Mothers | Not Overweight Mothers | |||||||

| n | Mean WHZ | SD | n | Mean WHZ | SD | Adj. β 3 | SE | |

| Maternal overweight in relation to mean WHZ | ||||||||

| Pooled | 34,193 | −0.55 | 1.37 | 194,771 | −0.98 | 1.40 | 0.29 ** | 0.01 |

| Afghanistan | 2161 | −0.17 | 1.45 | 7546 | −0.35 | 1.47 | 0.15 ** | 0.04 |

| Bangladesh | 1262 | −0.57 | 1.17 | 5348 | −0.96 | 1.13 | 0.28 ** | 0.04 |

| India | 28,715 | −0.59 | 1.36 | 176,992 | −1.02 | 1.39 | 0.28 ** | 0.01 |

| Maldives | 871 | −0.42 | 1.43 | 1245 | −0.57 | 1.38 | 0.16 * | 0.06 |

| Nepal | 326 | −0.23 | 1.12 | 1889 | −0.71 | 1.11 | 0.38 ** | 0.08 |

| Pakistan | 858 | −0.11 | 1.45 | 1751 | −0.44 | 1.49 | 0.34 ** | 0.06 |

| Overweight Mothers | Not Overweight Mothers | |||||||

| n | Overweight (%) | n | Overweight (%) | AOR 4 | SE | |||

| Maternal overweight in relation to overweight among children | ||||||||

| Pooled | 34,193 | 3.57 | 194,771 | 2.35 | 1.34 ** | 0.05 | ||

| Afghanistan | 2161 | 6.57 | 7546 | 5.13 | 1.27 | 0.19 | ||

| Bangladesh | 1262 | 2.38 | 5348 | 1.07 | 1.51 | 0.39 | ||

| India | 28,715 | 3.17 | 176,992 | 2.24 | 1.22 ** | 0.05 | ||

| Maldives | 871 | 6.2 | 1245 | 4.34 | 1.56 * | 0.32 | ||

| Nepal | 326 | 3.99 | 1889 | 0.95 | 5.19 ** | 2.49 | ||

| Pakistan | 858 | 8.16 | 1751 | 5.6 | 1.87 ** | 0.4 | ||

| Yes | No | |||||||

| n | Mean WHZ | SD | n | Mean WHZ | SD | Adj. β 2 | SE | |

| Feeding practices in relation to mean WHZ 2 | ||||||||

| Minimum meal frequency | 24,906 | −0.84 | 1.45 | 40,826 | −0.98 | 1.47 | 0.05 ** | 0.01 |

| Minimum diet diversity | 15,245 | −0.74 | 1.46 | 72,916 | −0.99 | 1.57 | 0.12 ** | 0.01 |

| Minimum acceptable diet | 6784 | −0.72 | 1.45 | 58,167 | −0.96 | 1.47 | 0.08 ** | 0.02 |

| Yes | No | |||||||

| n | % Overweight | n | % Overweight | AOR 3 | SE | |||

| Feeding practices in relation to % overweight 3 | ||||||||

| Minimum meal frequency 1 | 24,906 | 3 | 40,826 | 2.76 | 1.05 | 0.06 | ||

| Minimum diet diversity | 15,245 | 3.35 | 72,916 | 3.66 | 1.28 ** | 0.07 | ||

| Minimum acceptable diet | 6784 | 3.27 | 58,167 | 2.76 | 1.19 * | 0.1 | ||

| Adolescent Girls | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pooled | Stratified by Country 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AFG | BGD | IND | MDV | NPL | PAK | ||||||||||||||||

| n | Mean BMI | SD | Adj. β 2 | SE | Adj. β | S | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | |||||

| Factors in relation to mean BMI | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any education | 114,704 | 19.5 | 2.9 | 0.05 | 0.03 | −0.15 | 0.14 | 0.42 | 0.35 | 0.01 | 0.03 | -- | -- | 0.24 | 0.36 | −0.42 | 0.53 | ||||

| Wealthier | 68,431 | 19.8 | 3.2 | 0.47 ** | 0.02 | 0.37 * | 0.16 | 0.93 ** | 0.17 | 0.39 ** | 0.02 | 1.35 | 1.15 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 2.11 ** | 0.6 | ||||

| Urban | 33,469 | 19.9 | 3.3 | 0.36 ** | 0.02 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pooled | Stratified by Country 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AFG | BGD | IND | MDV | NPL | PAK | ||||||||||||||||

| n | % Overweight | AOR 3 | SE | AOR | SE | AOR | SE | AOR | SE | AOR | SE | AOR | SE | AOR | SE | ||||||

| Factors in relation to % overweight | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any education | 114,704 | 4.73 | 1.22 ** | 0.08 | 1.01 | 0.17 | 1.81 | 1.16 | 1.18 | 0.09 | -- | -- | 1.62 | 1.79 | 1.28 | 0.94 | |||||

| Wealthier | 68,431 | 6.54 | 2.46 ** | 0.09 | 1.42 | 0.3 | 2.73 ** | 0.71 | 2.27 ** | 0.09 | 3.08 | 2.38 | 2.07* | 0.7 | 16.68 * | 20.9 | |||||

| Urban | 33,469 | 7.68 | 1.74 ** | 0.06 | 1.17 | 0.26 | 1.52 | 0.35 | 1.77 ** | 0.06 | 1.11 | 1.28 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.43 | |||||

| Women | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Pooled | Stratified by Country 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AFG | BGD | IND | MDV | NPL | PAK | ||||||||||||||||

| n | Mean BMI | SD | Adj. β 2 | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | Adj. β | SE | |||||

| Factors in relation to mean BMI | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any education | 379,713 | 22.62 | 4.35 | 0.85 ** | 0.01 | 0.45 ** | 0.11 | 1.14 ** | 0.08 | 0.83 ** | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 1.03 ** | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.19 | ||||

| Wealthier | 350,054 | 23.23 | 4.45 | 1.50 ** | 0.01 | 0.36 ** | 0.1 | 1.64 ** | 0.08 | 1.41 ** | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.15 | 1.27 ** | 0.13 | 1.32 ** | 0.22 | ||||

| Urban | 172,480 | 23.63 | 4.66 | 1.20 ** | 0.02 | 1.53 ** | 0.15 | 1.34 ** | 0.1 | 1.16 ** | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.41 ** | 0.16 | 1.73 ** | 0.23 | ||||

| Pooled | Stratified by Country 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AFG | BGD | IND | MDV | NPL | PAK | ||||||||||||||||

| n | % Overweight | APR 3 | SE | APR | SE | APR | SE | APR | SE | APR | SE | APR | SE | APR | SE | ||||||

| Factors in relation to % overweight | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Any education | 379,713 | 25.04 | 1.36 ** | 0.01 | 1.15 ** | 0.06 | 1.56 ** | 0.06 | 1.37 ** | 0.01 | 1.07 | 0.04 | 1.53 ** | 0.1 | 1.12 * | 0.05 | |||||

| Wealthier | 350,054 | 29.89 | 2.20 ** | 0.02 | 1.18 ** | 0.06 | 2.14 ** | 0.1 | 2.17 ** | 0.02 | 1 | 0.04 | 1.87 ** | 0.14 | 1.52 ** | 0.1 | |||||

| Urban | 402,565 | 33.49 | 1.41 ** | 0.01 | 1.60 ** | 0.09 | 1.49 ** | 0.05 | 1.42 ** | 0.01 | 1.20 * | 0.09 | 1.11 ** | 0.08 | 1.29 ** | 0.06 | |||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harding, K.L.; Aguayo, V.M.; Webb, P. Trends and Correlates of Overweight among Pre-School Age Children, Adolescent Girls, and Adult Women in South Asia: An Analysis of Data from Twelve National Surveys in Six Countries over Twenty Years. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081899

Harding KL, Aguayo VM, Webb P. Trends and Correlates of Overweight among Pre-School Age Children, Adolescent Girls, and Adult Women in South Asia: An Analysis of Data from Twelve National Surveys in Six Countries over Twenty Years. Nutrients. 2019; 11(8):1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081899

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarding, Kassandra L., Victor M. Aguayo, and Patrick Webb. 2019. "Trends and Correlates of Overweight among Pre-School Age Children, Adolescent Girls, and Adult Women in South Asia: An Analysis of Data from Twelve National Surveys in Six Countries over Twenty Years" Nutrients 11, no. 8: 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081899

APA StyleHarding, K. L., Aguayo, V. M., & Webb, P. (2019). Trends and Correlates of Overweight among Pre-School Age Children, Adolescent Girls, and Adult Women in South Asia: An Analysis of Data from Twelve National Surveys in Six Countries over Twenty Years. Nutrients, 11(8), 1899. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081899