Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Behaviors of Cancer Patients Receiving Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics, Food Insecurity, Disease and Treatment

2.2.2. Food Safety Assessment

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics, Diseases Characteristics, and Food Security

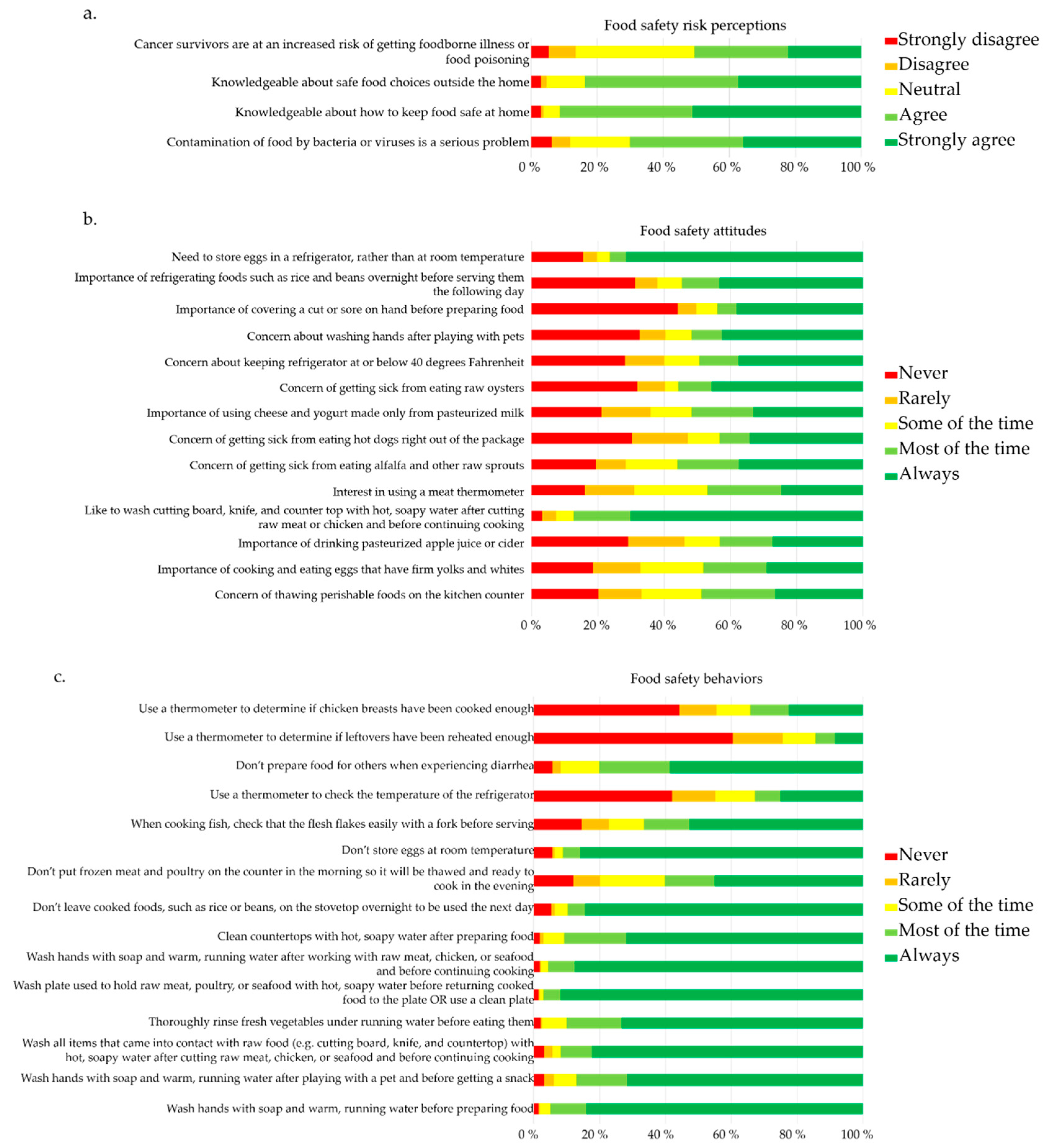

3.2. Risk Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behaviors

3.3. Food Preferences and Food Acquisition Behaviors

3.4. Food Safety Knowledge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scallan, E.; Hoekstra, R.M.; Angulo, F.J.; Tauxe, R.V.; Widdowson, M.A.; Roy, S.L.; Jones, J.L.; Griffin, P.M. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States-Major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, B.M.; O’Brien, S.J. The Occurrence and Prevention of Foodborne Disease in Vulnerable People. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2011, 8, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO/WHO. Risk Assessment of Listeria Monocytogenes; FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Clemons, K.V.; Salonen, J.H.; Issakainen, J.; Nikoskelainen, J.; McCullough, M.J.; Jorge, J.J.; Stevens, D.A. Molecular epidemiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in an immunocompromised host unit. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 68, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edvinsson, B.; Lappalainen, M.; Anttila, V.J.; Paetau, A.; Evengård, B. Toxoplasmosis in immunocompromized patients. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 41, 368–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, H.M.; Campbell, B.J.; Hart, C.A.; Mpofu, C.; Nayar, M.; Singh, R.; Englyst, H.; Williams, H.F.; Rhodes, J.M. Enhanced Escherichia coli adherence and invasion in Crohn’s disease and colon cancer. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D. Cancer Statistics 2019. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bow, E.J. Infection risk and cancer chemotherapy: the impact of the chemotherapeutic regimen in patients with lymphoma and solid tissue malignancies. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1998, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chen, G.; Kendall, P.A.; Hillers, V.N.; Medeiros, L.C. Qualitative Studies of the Food Safety Knowledge and Perceptions of Transplant Patients. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, L.C.; Chen, G.; Kendall, P.; Hillers, V.N. Food Safety Issues for Cancer and Organ Transplant Patients. Nutr. Clin. Care 2004, 7, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hillers, V.N.; Medeiros, L.; Kendall, P.; Chen, G.; DiMascola, S. Consumer Food-Handling Behaviors Associated with Prevention of 13 Foodborne Illnesses. J. Food Prot. 2016, 66, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, L.C.; Kendall, P.; Hillers, V.; Chen, G.; Dimascola, S. Identification and classification of consumer food-handling behaviors for food safety education. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2001, 101, 1326–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. Report of the Fda Retail Food Program Database of Foodborne Illness Risk Factors; Food and Drug Administration: White Oak, MD, USA, 2000.

- Kempson, K.M.; Keenan, D.P.; Sadani, P.S.; Ridlen, S. Food management practices used by people with limited resources to maintain food sufficiency as reported by nutrition educators. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1795–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.; Redmond, E. Food Safety Knowledge and Self-Reported Food-Handling Practices in Cancer Treatment. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2018, 45, E98–E110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langiano, E.; Ferrara, M.; Lanni, L.; Viscardi, V.; Abbatecola, A.M.; De Vito, E. Food safety at home: Knowledge and practices of consumers. J. Public Health 2012, 20, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, L.C.; Chen, G.; Hillers, V.N.; Kendall, P.A. Discovery and Development of Educational Strategies To Encourage Safe Food Handling Behaviors in Cancer Patients. J. Food Prot. 2008, 71, 1666–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furness, B.W.; Simon, P.A.; Wold, C.M.; Asarian-Anderson, J. Prevalence and predictors of food insecurity among low-income households in Los Angeles County. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Food Insecurity, Heart Disease, Physical Activity; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001; Volume 12.

- Shariff, Z.M.; Khor, G.L. Household food insecurity and coping strategies in a poor rural community in Malaysia. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2009, 2, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, K.; Ilic, S.; Paden, H.; Lustberg, M.; Grenade, C.; Bhatt, A.; Diaz, D.; Beery, A.; Hatsu, I. An evaluation of factors predicting diet quality among cancer patients. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Research Service. USDA US Adult Food Security Survey Module: Three-Stage Design, with Screeners 2012. pp. 1–7. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8279/ad2012.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Anater, A.S.; Mcwilliams, R.; Latkin, C.A. Food Acquisition Practices Used by Food-Insecure Individuals When They Are Concerned About Having Sufficient Food for Themselves and Their Households. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2011, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Ilic, S.; LeJeune, J.; Lewis Ivey, M.L.; Miller, S. Delphi expert elicitation to prioritize food safety management practices in greenhouse production of tomatoes in the United States. Food Control 2017, 78, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, G.G. Household Income 2017; US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2018.

- Janz, N.K.; Champion, V.L.; Strecher, V.J. The Health Belief Model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Lewis, F.M., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, J.J. Foodborne illness incidence rates and food safety risks for populations of low socioeconomic status and minority race/ethnicity: a review of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 3634–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Wilson, A.N.S.; Bednar, C.; Kennon, L. Food Safety Knowledge and Behaviors of Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) Program Participants in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2016, 71, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenrich, T.; Cason, K.; Lv, N.; Kassab, C. Food safety knowledge and practices of low income adults in Pennsylvania. Food Prot. Trends 2003, 23, 326–335. [Google Scholar]

- Todd, J.; Schmidt, M.; Christain, J.; Williams, R. Controversies in Cancer Care The Low-Bacteria Diet for. Cancer Pract. 1999, 7, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, H.R.; Sadeghi, N.; Agrawal, D.; Johnson, D.H.; Gupta, A. Things We Do For No Reason: Neutropenic Diet. J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 13, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMarco-Crook, C.; Xiao, H. Diet-Based Strategies for Cancer Chemoprevention: The Role of Combination Regimens Using Dietary Bioactive Components. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 6, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feeding America. Map the Meal Gap 2019; Feeding America: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, L.A.; Modesitt, S.C.; Brody, A.C.; Leggin, A.B. Food Insecurity Among Cancer Patients in Kentucky: A Pilot Study. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017, 2, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Commerce; Economics and Statistics Administration; U.S. Census Bureau. Ohio: 2010 Summary Population and Housing Characteristics; 2012. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8279/ad2012.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Ohio Development Services Agency. Educational Attainment: Ohio by the Numbers; Ohio Development Services Agency: Columbus, OH, USA, 2017.

- Ohio Department of Job and Family Services. Caseload Summary Statistics Report October 2018; Ohio Department of Job and Family Services: Columbus, OH, USA, 2018.

- Cronin, K.A.; Lake, A.J.; Scott, S.; Sherman, R.L.; Noone, A.M.; Howlader, N.; Henley, S.J.; Anderson, R.N.; Firth, A.U.; Ma, J.; et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, part I: National cancer statistics. Cancer 2018, 124, 2785–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Categories | na | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 192 | 66.90 |

| Male | 95 | 33.10 | |

| Age | 18–29 | 7 | 2.45 |

| 30–39 | 19 | 6.64 | |

| 40–49 | 38 | 13.29 | |

| 50–59 | 97 | 33.92 | |

| 60–69 | 84 | 29.37 | |

| >70 | 41 | 14.34 | |

| Race | Asian | 2 | 0.70 |

| Black/African | 27 | 9.41 | |

| Hispanic | 2 | 0.70 | |

| Native American | 3 | 1.05 | |

| White | 250 | 87.11 | |

| Other | 3 | 1.05 | |

| Marital status | Married | 175 | 60.76 |

| Single | 31 | 10.76 | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 77 | 26.74 | |

| Other | 5 | 1.74 | |

| Highest level of education | <H.S. b | 81 | 28.13 |

| H.S./GED c | 38 | 13.19 | |

| 1–2 college | 63 | 21.88 | |

| ≥college | 106 | 36.81 | |

| Employment status | 40+ h/wkd | 96 | 33.33 |

| ≤40 h/wkd | 40 | 13.89 | |

| Home | 19 | 6.60 | |

| Retired | 92 | 31.94 | |

| None | 41 | 14.24 | |

| What is your household’s monthly income? ($) | <$1000 | 25 | 8.96 |

| <$2000 | 53 | 19.00 | |

| <$3000 | 56 | 20.07 | |

| <$4000 | 45 | 16.13 | |

| ≥$4000 | 100 | 35.84 | |

| How many people live in your household? | 1 | 55 | 19.1 |

| 2 | 131 | 45.49 | |

| 3 | 44 | 15.28 | |

| ≥4 | 31 | 10.76 | |

| ≥5 | 27 | 9.38 | |

| How many children (<18 yrs.) live in your household? | 0 | 209 | 72.60 |

| 1 | 34 | 11.81 | |

| 2 | 26 | 9.03 | |

| 3 | 14 | 4.86 | |

| ≥4 | 5 | 1.74 | |

| What is your health insurance status? | None | 4 | 1.39 |

| Private | 143 | 49.83 | |

| Public | 39 | 13.59 | |

| Medicare | 101 | 35.19 | |

| Have you had to borrow money to pay for healthcare? | Yes | 26 | 9.09 |

| No | 260 | 90.91 | |

| Have you had to pay your bills late due to medical expenses? | Yes | 69 | 24.13 |

| No | 217 | 75.87 | |

| Which food assistance programs do you participate in? | SNAP e/food stamps | 32 | 11.19 |

| WIC f | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 5 | 1.75 | |

| None | 249 | 87.06 | |

| Receive foods from a food bank, a food pantry, or a soup kitchen | Yes | 28 | 9.79 |

| No | 258 | 90.21 | |

| What is the best description for where you live? | Urban | 55 | 19.57 |

| Rural | 102 | 36.3 | |

| Suburban | 124 | 44.13 | |

| What is your smoking status? | Current | 33 | 11.46 |

| Former | 107 | 37.15 | |

| Never | 148 | 51.39 | |

| If current smoker, how often do you smoke? | 0 | 251 | 87.46 |

| Daily | 30 | 10.45 | |

| 4–6d/w f | 3 | 1.05 | |

| 2–3d/w f | 2 | 0.7 | |

| 1d/w f | 1 | 0.35 | |

| Do you use any recreational drugs? | Yes | 10 | 3.47 |

| No | 278 | 96.53 | |

| Do you drink alcohol? | Yes | 117 | 40.63 |

| No | 171 | 59.38 | |

| If yes, how often? | 0 | 171 | 60 |

| Daily | 19 | 6.67 | |

| 4–6d/w g | 16 | 5.61 | |

| 2–3d/w g | 29 | 10.18 | |

| 1d/w g | 50 | 17.54 |

| Cancer type | na | % |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | 105 | 38.6 |

| Prostate | 43 | 15.81 |

| Ovarian | 14 | 5.15 |

| Cervical | 15 | 5.51 |

| Colon/Rectum | 31 | 11.4 |

| Lung | 11 | 4.04 |

| Other | 53 | 19.49 |

| Food Safety Topic | Items (n) | Average (%) | Standard Deviation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Food Safety | 11 | 70.74 | 15.53 |

| Cross-Contamination (Separation) | 8 | 83.03 | 15.62 |

| Food Preparation | 8 | 73.70 | 20.43 |

| Food Storage (Chill) | 8 | 69.53 | 17.47 |

| Clean Up (Cleaning/Hygiene) | 10 | 77.64 | 17.88 |

| Overall Food Safety Knowledge | 45 | 74.77 | 12.24 |

| Socioeconomic Factor | Food Safety Knowledge Scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Average (%) | Standard Deviation (%) | Significance (P) | |

| Income ($) | <$1000 * | 68.16 | 17.93 | <0.005 |

| <$2000 | 72.54 | 9.36 | ||

| <$3000 | 74.01 | 15.68 | ||

| <$4000 * | 78.72 | 7.98 | ||

| ≥$4000 * | 76.62 | 9.92 | ||

| Food Assistance (Federal) | SNAP * | 66.76 | 16.95 | <0.001 |

| Other | 71.11 | 7.86 | ||

| None * | 75.94 | 11.21 | ||

| Food Assistance (Private) | Receive | 65.63 | 16.18 | <0.001 |

| Don’t Receive | 75.77 | 11.39 | ||

| Food Security | Secure | 75.96 | 11.05 | <0.001 |

| Insecure | 69.74 | 15.50 | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paden, H.; Hatsu, I.; Kane, K.; Lustberg, M.; Grenade, C.; Bhatt, A.; Diaz Pardo, D.; Beery, A.; Ilic, S. Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Behaviors of Cancer Patients Receiving Treatment. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081897

Paden H, Hatsu I, Kane K, Lustberg M, Grenade C, Bhatt A, Diaz Pardo D, Beery A, Ilic S. Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Behaviors of Cancer Patients Receiving Treatment. Nutrients. 2019; 11(8):1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081897

Chicago/Turabian StylePaden, Holly, Irene Hatsu, Kathleen Kane, Maryam Lustberg, Cassandra Grenade, Aashish Bhatt, Dayssy Diaz Pardo, Anna Beery, and Sanja Ilic. 2019. "Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Behaviors of Cancer Patients Receiving Treatment" Nutrients 11, no. 8: 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081897

APA StylePaden, H., Hatsu, I., Kane, K., Lustberg, M., Grenade, C., Bhatt, A., Diaz Pardo, D., Beery, A., & Ilic, S. (2019). Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Behaviors of Cancer Patients Receiving Treatment. Nutrients, 11(8), 1897. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081897