The Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet on Metabolic Syndrome in Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

:1. Introduction

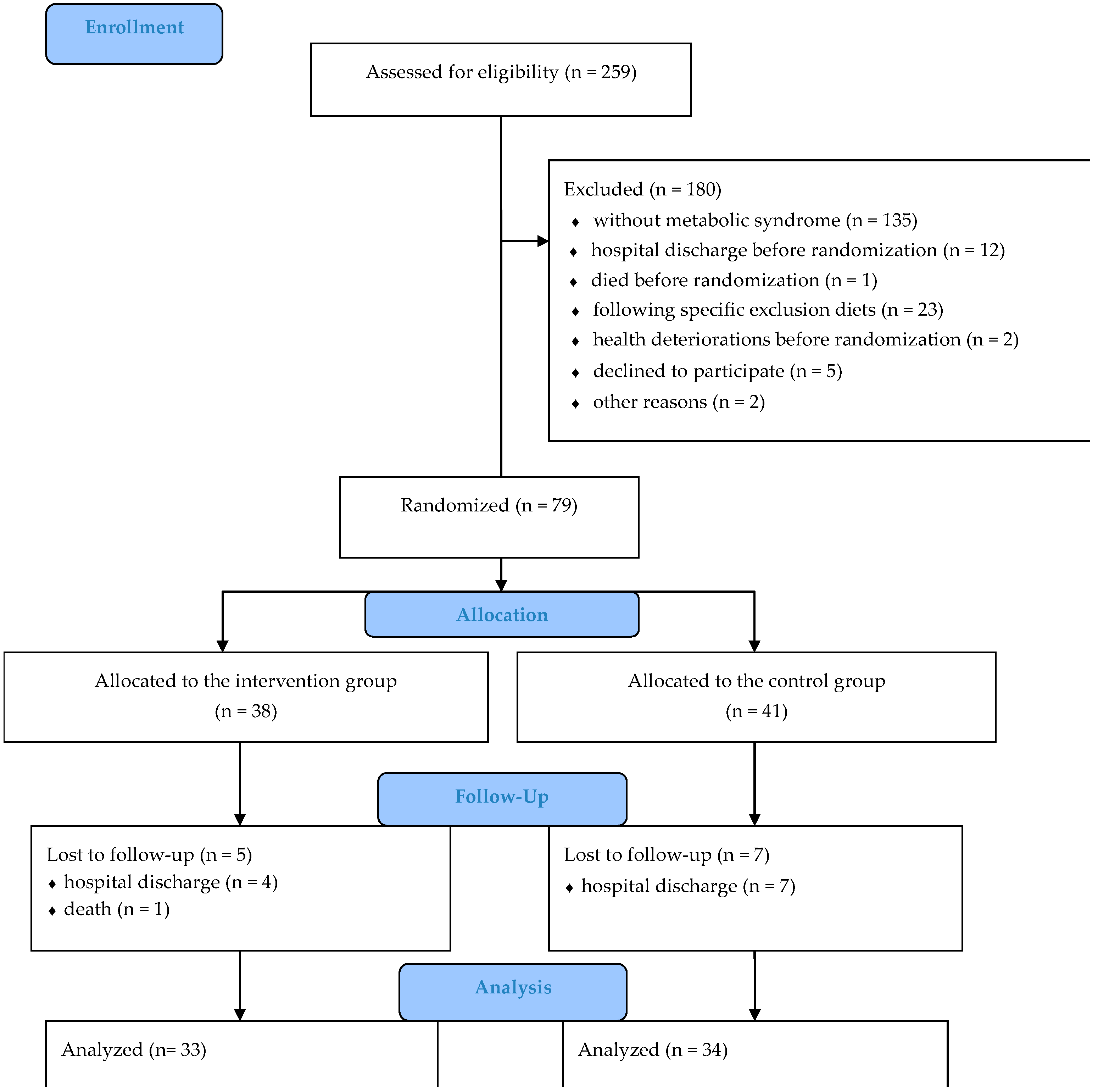

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants and Setting

2.2. Randomization

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

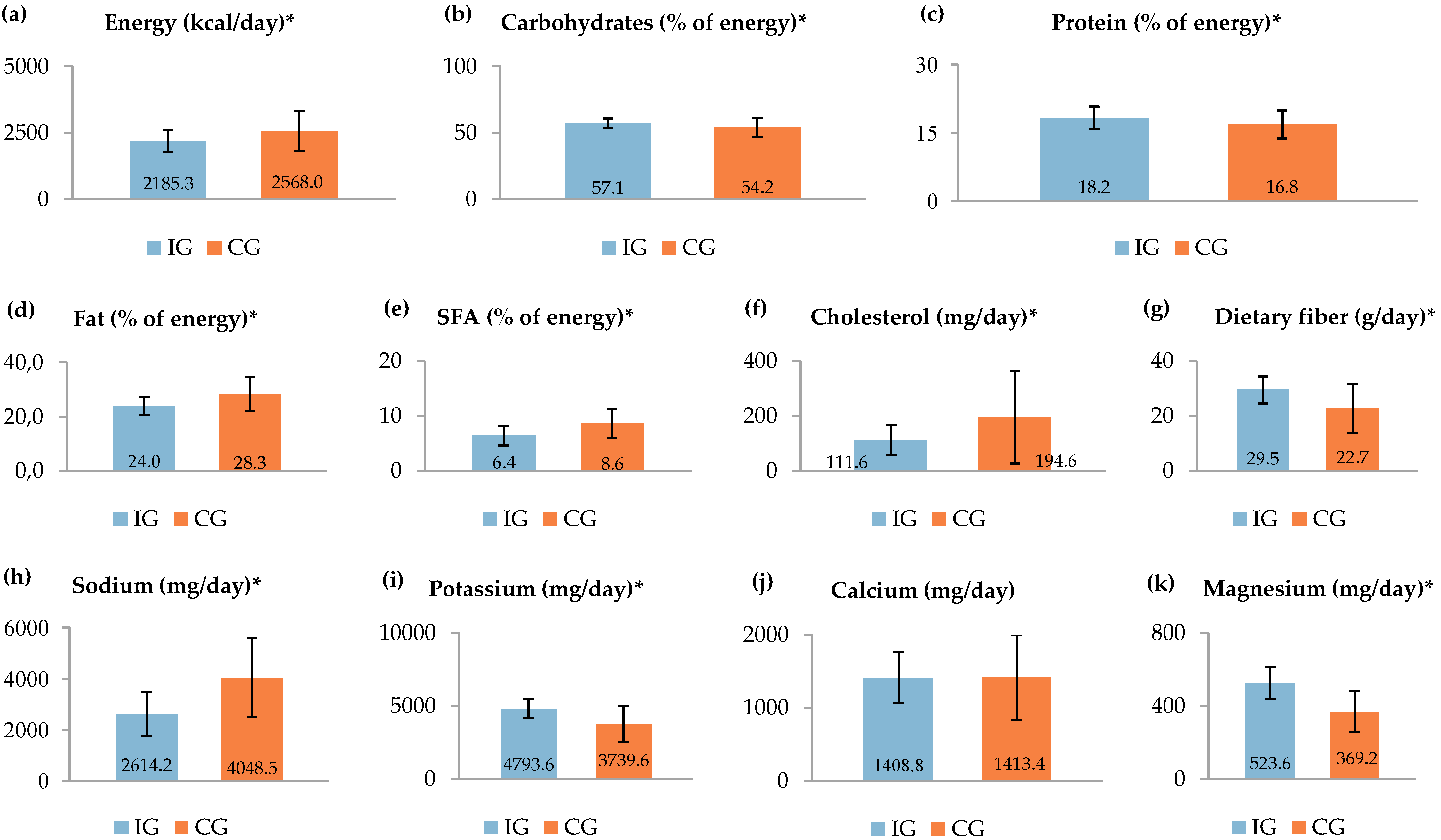

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kassi, E.; Pervanidou, P.; Kaltsas, G.; Chrousos, G. Metabolic syndrome: Definitions and controversies. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Li, X.; Adams, H.; Kubena, K.; Guo, S. Etiology of metabolic syndrome and dietary intervention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saklayen, M.G. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, R.; Li, W.; Lun, Z.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z.; Kanu, J.S.; Qiu, S.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Y. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Mainland China: A meta-analysis of published studies. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malhotra, N.; Grover, S.; Chakrabarti, S.; Kulhara, P. Metabolic syndrome in schizophrenia. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2013, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khalil, R.B. The metabolic syndrome and schizophrenia: A comorbidity or an association? J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2013, 4, 174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Martynikhin, I.; Tanyanskiy, D.; Rotar, O.; Solntsev, V.; Sokolian, N.; Neznanov, N.; Konradi, A.; Shlyakhto, E.; Denisenko, A. Risk of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: Comparative study with population of bank employees in Russia. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2013, 2, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capasso, R.M.; Lineberry, T.W.; Bostwick, J.M.; Decker, P.A.; St Sauver, J. Mortality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: An Olmsted County, Minnesota cohort: 1950–2005. Schizophr. Res. 2008, 98, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipasquale, S.; Pariante, C.M.; Dazzan, P.; Aguglia, E.; McGuire, P.; Mondelli, V. The dietary pattern of patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patel, J.K.; Buckley, P.F.; Woolson, S.; Hamer, R.M.; McEvoy, J.P.; Perkins, D.O.; Lieberman, J.A. CAFE Investigators. Metabolic profiles of second-generation antipsychotics in early psychosis: Findings from the CAFE study. Schizophr. Res. 2009, 111, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.J.; Lim, S.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Shin, I.S.; Yoon, J.S.; Yang, S.J.; et al. Low dietary intake of n-3 fatty acids, niacin, folate, and vitamin C in Korean patients with schizophrenia and the development of dietary guidelines for schizophrenia. Nutr. Res. 2017, 45, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratliff, J.C.; Palmese, L.B.; Reutenauer, E.L.; Liskov, E.; Grilo, C.M.; Tek, C. The effect of dietary and physical activity pattern on metabolic profile in individuals with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, S.; Birtwistle, J.; Roe, L.; Thompson, C. The unhealthy lifestyle of people with schizophrenia. Psychol. Med. 1999, 29, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli-Muñoz, A.J.; Fortea, M.I.; Salorio, P.; Gallego-Gomez, J.I.; Sánchez-Bautista, S.; Balanza, S. Dietary habits of patients with schizophrenia: A self-reported questionnaire survey. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 21, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.; Kumagai, T.; Kimura, M.; Koike, S.; Shimizu, T. Dietary intake in body mass index differences in community-based Japanese patients with schizophrenia. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 639–645. [Google Scholar]

- Siri-Tarino, P.W.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B.; Krauss, R.M. Saturated fat, carbohydrate, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. JAMA 2002, 288, 2569–2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delzenne, N.M.; Cani, P.D. A place for dietary fibre in the management of the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2005, 8, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, P.; Ekmekcioglu, C. Impact of salt intake on the pathogenesis and treatment of hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 956, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, L.S.; de Moraes, M.M.; de Carvalho, G.X.; Koifman, R.J. Nutritional interventions in metabolic syndrome: A systematic review. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2011, 97, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sacks, F.M.; Svetkey, L.P.; Vollmer, W.M.; Appel, L.J.; Bray, G.A.; Harsha, D.; Obarzanek, E.; Conlin, P.R.; Miller, E.R.; Simons-Morton, D.G.; et al. DASH—Sodium Collaborative Research Group. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, J.A.; Babyak, M.A.; Hinderliter, A.; Watkins, L.L.; Craighead, L.; Lin, P.H.; Caccia, C.; Johnson, J.; Waugh, R.; Sherwood, A. Effects of the DASH diet alone and in combination with exercise and weight loss on blood pressure and cardiovascular biomarkers in men and women with high blood pressure: The ENCORE study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Sciences, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. DASH Eating Plan. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/public/heart/new_dash.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Hill, A.M.; Harris Jackson, K.A.; Roussell, M.A.; West, S.G.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Type and amount of dietary protein in the treatment of metabolic syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saneei, P.; Hashemipour, M.; Kelishadi, R.; Rajaei, S.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Effects of recommendations to follow the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet v. usual dietary advice on childhood metabolic syndrome: A randomised cross-over clinical trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 2250–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azadbakht, L.; Mirmiran, P.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Azizi, T.; Azizi, F. Beneficial effects of a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 2823–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shenoy, S.F.; Poston, W.S.; Reeves, R.S.; Kazaks, A.G.; Holt, R.R.; Keen, C.L.; Chen, H.J.; Haddock, C.K.; Winters, B.L.; Khoo, C.S.; et al. Weight loss in individuals with metabolic syndrome given DASH diet counseling when provided a low sodium vegetable juice: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chiavaroli, L.; Viquiliouk, E.; Nishi, S.K.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Rahelić, D.; Kahleová, H.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Kendall, C.W.; Sievenpiper, J.L. DASH dietary pattern and cardiometabolic outcomes: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Nutrients 2019, 11, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joseph, J.; Depp, C.; Shih, P.B.; Chadenhead, K.S.; Schmid-Schönbein, G. Modified Mediterranean diet for enrichment of short chain fatty acids: Potential adjunctive therapeutic to target immune and metabolic dysfunction in schizophrenia? Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- StatSoft, Inc. Electronic Statistics Textbook. Available online: http://www.statsoft.com/Textbook/Power-Analysis (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Ministry of Health. Odluka o Standardu Prehrane Bolesnika u Bolnicama. [The Decision on the Nutritional Standard for Hospitalized Patients]; Official Gazette of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2015. (In Croatian) [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. Choose MyPlate. Available online: https://www.choosemyplate.gov (accessed on 10 August 2019).

- Liddle, P.F.; Ngan, E.T.; Duffield, G.; Kho, K.; Warren, A.J. Signs and symptoms of psychotic illness (SSPI): A rating scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 2002, 180, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.D.; Nieman, D.C. Anthropometry. In Nutritional Assessment, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 160–213. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499–502. [Google Scholar]

- Frese, E.M.; Fick, A.; Sadowsky, H.S. Blood pressure measurement guidelines for physical therapists. Cardiopulm. Phys. Ther. J. 2011, 22, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Hert, M.; Schreurs, V.; Vancampfort, D.; Van Winkel, R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: A review. World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandiari, S.; Bahadoran, Z.; Mirmiran, P.; Tohidi, M.; Azizi, F. Adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension trial (DASH) diet is inversely associated with incidence of insulin resistance in adults: The Tehran lipid and glucose study. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2017, 61, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gelli, C.; Tarocchi, M.; Abenavoli, L.; Di Renzo, L.; Galli, A.; De Lorenzo, A. Effect of a counseling-supported treatment with the Mediterranean diet and physical activity on the severity of the non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 3150–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obarzanek, E.; Sacks, F.M.; Vollmer, W.M.; Bray, G.A.; Miller, E.R., 3rd; Lin, P.H.; Karanja, N.M.; Most-Windhauser, M.M.; Moore, T.J.; Swain, J.F.; et al. DASH Research Group. Effects on blood lipids of a blood pressure-lowering diet: The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi Zade, M.; Telkabadi, M.H.; Bahmani, F.; Salehi, B.; Farshbaf, S.; Asemi, Z. The effects of DASH diet on weight loss and metabolic status in adults with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized clinical trial. Liver Int. 2016, 36, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, L.O.; Martindale-Adams, J.L.; Burns, R.; Graney, M.J.; Zuber, J.K.; Kennedy, S.E. Potential explanations for control group benefit. Clin. Trials 2012, 9, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasdale, S.B.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Watkins, A.; Curtis, J.; Kalucy, M.; Samaras, K. A nutrition intervention is effective in improving dietary components linked to cardiometabolic risk in youth with first-episode psychosis. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1987–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baker, A.L.; Turner, A.; Kelly, P.J.; Spring, B.; Callister, R.; Collins, C.E.; Woodcock, K.L.; Kay-Lambkin, F.J.; Devir, H.; Lewin, T.J. ′Better Health Choices′ by telephone: A feasibility trial of improving diet and physical activity in people diagnosed with psychotic disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 220, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | IG (n = 33) n (%) or Mean (SD) | CG (n = 34) n (%) or Mean (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| male | 28 (84.8) | 29 (85.3) | 0.959 a |

| female | 5 (15.2) | 5 (14.7) | |

| Age (years) | 53.2 (8.9) | 50.7 (8.0) | 0.228 b |

| Educational level | |||

| no formal education or primary education | 12 (36.4) | 7 (20.6) | 0.568 a |

| secondary education or higher | 21 (63.6) | 27 (79.4) | |

| Working status | |||

| employed | 0 (0) d | 1 (2.9) d | 0.450 a |

| unemployed | 15 (45.5) | 11 (32.4) | |

| retired | 17 (51.5) | 19 (55.9) | |

| receiver of social welfare | 1 (3.0) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Marital status | |||

| single | 29 (87.9) | 31 (91.2) | 0.967 a |

| married/in a relationship | 4 (12.1) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Residential area | |||

| urban | 18 (54.5) | 11 (32.4) | 0.113 a |

| rural | 15 (45.5) | 23 (67.6) | |

| Illness duration (years) | 17.6 (12.7) | 17.9 (12.6) | 0.808 c |

| Type of schizophrenia | |||

| paranoid | 22 (66.7) | 27 (79.4) | 0.171 a |

| residual | 11 (33.3) | 5 (14.7) | |

| other | 0 (0) d | 2 (5.9) d | |

| Deprivation of legal capacity | |||

| yes | 10 (30.3) | 10 (29.4) | 0.851 a |

| no | 23 (69.7) | 24 (70.6) | |

| Number of antipsychotics | |||

| 1 | 3 (9.1) | 9 (26.5) | 0.199 c |

| 2–3 | 27 (81.8) | 22 (64.7) | |

| >3 | 3 (9.1) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Type of antipsychotics | |||

| typical | 1 (3.0) | 2 (5.9) | 0.511 a |

| atypical | 20 (60.6) | 16 (47.1) | |

| both | 12 (36.4) | 16 (47.1) | |

| Taking antidepressants | |||

| yes | 3 (9.1) | 4 (11.8) | 0.721 a |

| no | 30 (90.9) | 30 (88.2) | |

| Taking mood stabilizers | |||

| yes | 13 (39.4) | 13 (38.2) | 0.926 a |

| no | 20 (60.6) | 21 (61.8) | |

| Taking antiepileptics | |||

| yes | 2 (6.1) | 4 (11.8) | 0.414 a |

| no | 31 (93.9) | 30 (88.2) | |

| Taking anxiolytics | |||

| yes | 19 (57.6) | 21 (61.8) | 0.727 a |

| no | 14 (42.4) | 13 (38.2) | |

| Taking antiparkinsonics | |||

| yes | 11 (33.3) | 9 (26.5) | 0.539 a |

| no | 22 (66.7) | 25 (73.5) | |

| Taking antihypertensive drug therapy | |||

| yes | 11 (33.3) | 8 (23.5) | 0.373 a |

| no | 22 (66.7) | 26 (76.5) | |

| Taking hypertriglyceridemia medications | |||

| yes | 5 (15.2) | 4 (11.8) | 0.900 a |

| no | 28 (84.8) | 30 (88.2) | |

| Taking hyperglycemia medications | |||

| yes | 0 (0) | 5 (14.7) | 0.028 a,e |

| no | 33 (100.0) | 29 (85.3) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| current smokers | 24 (72.7) | 24 (70.6) | 0.934 a |

| ex-smokers/never smokers | 9 (27.3) | 10 (29.4) | |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| yes | 2 (6.1) | 3 (8.8) | 0.972 a |

| no | 31 (93.9) | 31 (91.2) | |

| Physical activity | |||

| inactive | 22 (66.7) | 24 (70.6) | 0.789 a |

| moderate activity | 11 (33.3) | 9 (26.5) | |

| high activity | 0 (0) d | 1 (2.9) d | |

| Additional daily energy intake (kJ/kcal) | 2259.8/540.1 (2278.2/544.5) | 1812.9/433.3 (2279.9/544.9) | 0.425 c |

| The overall SSPI score f | 26.5 (13.1) | 30.0 (10.9) | 0.236 b |

| Parameter | IG (n = 33) | pb | CG (n = 34) | pb | pc | pd | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | At 3 Months | EE (%) (95% CI) a | Baseline | At 3 Months | EE (%) (95% CI) a | |||||

| Mean (SD) (95% CI) | Mean (SD) (95% CI) | Mean (SD) (95% CI) | Mean (SD) (95% CI) | |||||||

| BW (kg) | 89.60 (15.81) (83.99–95.21) | 87.17 (15.52) (81.67–92.67) | 15.7 (14.6–16.7) | <0.001 | 88.56 (13.97) (83.69–93.43) | 86.92 (13.93) (82.06–91.78) | 11.8 (10.5–13.1) | 0.018 | 0.776 | 0.943 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.95 (5.21) (27.1–30.8) | 28.16 (5.04) (26.37–29.95) | 15.7 (15.3–16.1) | <0.001 | 27.47 (3.90) (26.11–28.83) | 26.96 (3.95) (25.58–28.34) | 12.8 (12.3–13.2) | 0.019 | 0.189 | 0.281 |

| WC (cm) | 109.09 (12.25) (104.75–113.43) | 105.55 (12.22) (101.22–109.88) | 29.0 (27.7–30.3) | <0.001 | 106.92 (9.40) (103.64–110.2) | 104.47 (9.75) (101.07–107.87) | 25.1 (23.7–26.6) | 0.002 | 0.417 | 0.690 |

| HC (cm) | 107.89 (10.55) (104.15–111.63) | 106.14 (10.21) (102.52–109.76) | 17.2 (16.3–18.0) | <0.001 | 106.57 (6.90) (104.16–108.98) | 105.64 (7.20) (103.13–108.15) | 13.0 (11.9–14.1) | 0.098 | 0.546 | 0.817 |

| WHR | 1.01 (0.05) (0.99–1.03) | 0.99 (0.06) (0.97–1.01) | 27.2 (27.2–27.2) | 0.015 | 1.00 (0.05) (0.98–1.02) | 0.99 (0.05) (0.97–1.01) | 27.7 (27.7–27.7) | 0.006 | 0.531 | 0.684 |

| % BF e | 28.32 (9.22) (25.05–31.59) | 28.34 (8.76) (25.18–31.50) | 6.9 (6.1–7.7) | 0.165 | 26.79 (7.97) (23.97–29.61) | 27.54 (8.22) (24.62–30.46) | −9.1 (−10.1 to −8.0) | 0.185 | 0.472 | 0.703 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 130.38 (15.53) (124.87–135.89) | 126.52 (13.05) (121.89–131.15) | 29.6 (24.6–34.7) | 0.144 | 129.41 (19.98) (122.44–136.38) | 126.25 (17.90) (120.00–132.5) | 17.7 (10.3–25.0) | 0.399 | 0.826 | 0.945 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 85.53 (9.31) (82.23–88.83) | 80.23 (9.93) (76.71–83.75) | 53.4 (50.1–56.7) | 0.004 | 84.34 (9.70) (80.95–87.72) | 82.72 (10.03) (79.22–86.22) | 16.1 (12.9–19.4) | 0.332 | 0.610 | 0.310 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 2.15 (0.92) (1.83–2.47) | 2.32 (1.21) (1.89–2.75) | −14.1 (−14.4 to −13.8) | 0.276 | 1.81 (0.82) (1.52–2.10) | 1.83 (0.79) (1.56–2.10) | −3.0 (−3.3 to −2.7) | 0.890 | 0.118 | 0.056 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 0.92 (0.31) (0.81–1.03) | 0.95 (0.30) (0.84–1.06) | −11.1 (−11.2 to −11.1) | 0.169 | 0.93 (0.19) (0.86–1.00) | 1.00 (0.29) (0.90–1.10) | −25.0 (−25.1 to −24.9) | 0.085 | 0.859 | 0.481 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) f | 3.19 (1.11) (2.79–3.59) | 3.04 (0.86) (2.73–3.35) | 17.0 (16.7–17.3) | 0.336 | 3.07 (0.90) (2.76–3.38) | 3.27 (0.78) (3.00–3.54) | −25.5 (−25.8 to −25.2) | 0.188 | 0.646 | 0.255 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.08 (1.25) (4.64–5.52) | 5.02 (1.07) (4.64–5.40) | 5.4 (5.0–5.7) | 0.746 | 4.83 (1.08) (4.45–5.21) | 5.09 (1.03) (4.73–5.45) | −25.2 (−25.5 to −24.8) | 0.195 | 0.386 | 0.795 |

| GLC (mmol/L) | 5.59 (0.78) (5.32–5.86) | 5.34 (0.53) (5.15–5.53) | 47.3 (47.1–47.6) | 0.101 | 6.21 (1.73) (5.61–6.81) | 5.69 (1.69) (5.10–6.28) | 30.8 (30.1–31.4) | 0.146 | 0.061 | 0.254 |

| Parameter (95% CI for 1 Proportion) a | IG (n = 33) | pb | CG (n = 34) | pb | pc | pd | OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline n (%) | At 3 Months n (%) | Baseline n (%) | At 3 Months n (%) | ||||||

| elevated WC (≥94 cm men; ≥80 cm women) | 31 (93.9) (0.80–0.99) | 29 (87.9) (0.72–0.97) | 0.391 | 34 (100.0) (0.90–1.00) | 32 (94.1) (0.80–0.99) | 0.151 e | 0.238 e | 0.371 | 1.0 (0.50–2.03) |

| elevated TG (≥1.7 mmol/L) or pharmacotherapy for elevated TG | 27 (81.8) (0.65–0.93) | 24 (72.7) (0.54–0.87) | 0.378 | 19 (55.9) (0.38–0.73) | 19 (55.9) (0.38–0.73) | 1.000 | 0.022 | 0.150 | 1.1 (0.49–2.61) |

| low HDL-C (<1.0 mmol/L men; <1.3 mmol/L women) or pharmacotherapy for low HDL-C | 26 (78.8) (0.61–0.91) | 21 (63.6) (0.45–0.80) | 0.174 | 24 (70.6) (0.53–0.85) | 17 (50.0) (0.32–0.68) | 0.082 | 0.440 | 0.260 | 0.9 (0.38–2.04) |

| elevated BP (SBP ≥130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥85 mmHg) or pharmacotherapy for elevated BP | 8 (24.2) (0.11–0.42) | 10 (30.3) (0.16–0.49) | 0.580 | 8 (23.5) (0.11–0.41) | 17 (50.0) (0.32–0.68) | 0.023 | 0.945 | 0.100 | 1.7 (0.49–5.95) |

| elevated fasting GLC (≥5.6 mmol/L) or pharmacotherapy for elevated fasting GLC | 15 (45.5) (0.28–0.64) | 10 (30.3) (0.16–0.49) | 0.204 | 19 (55.9) (0.38–0.73) | 18 (52.9) (0.35–0.70) | 0.807 | 0.393 | 0.060 | 1.4 (0.51–3.97) |

| MetS | 33 (100.0) (0.89–1.00) | 25 (75.8) (0.58–0.89) | 0.002 e | 34 (100.0) (0.90–1.00) | 23 (67.7) (0.49–0.83) | 0.0003 e | 1.000 | 0.461 | 0.9 (0.43–1.87) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorić, T.; Mavar, M.; Rumbak, I. The Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet on Metabolic Syndrome in Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122950

Sorić T, Mavar M, Rumbak I. The Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet on Metabolic Syndrome in Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2019; 11(12):2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122950

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorić, Tamara, Mladen Mavar, and Ivana Rumbak. 2019. "The Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet on Metabolic Syndrome in Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Nutrients 11, no. 12: 2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122950

APA StyleSorić, T., Mavar, M., & Rumbak, I. (2019). The Effects of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet on Metabolic Syndrome in Hospitalized Schizophrenic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 11(12), 2950. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122950