Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

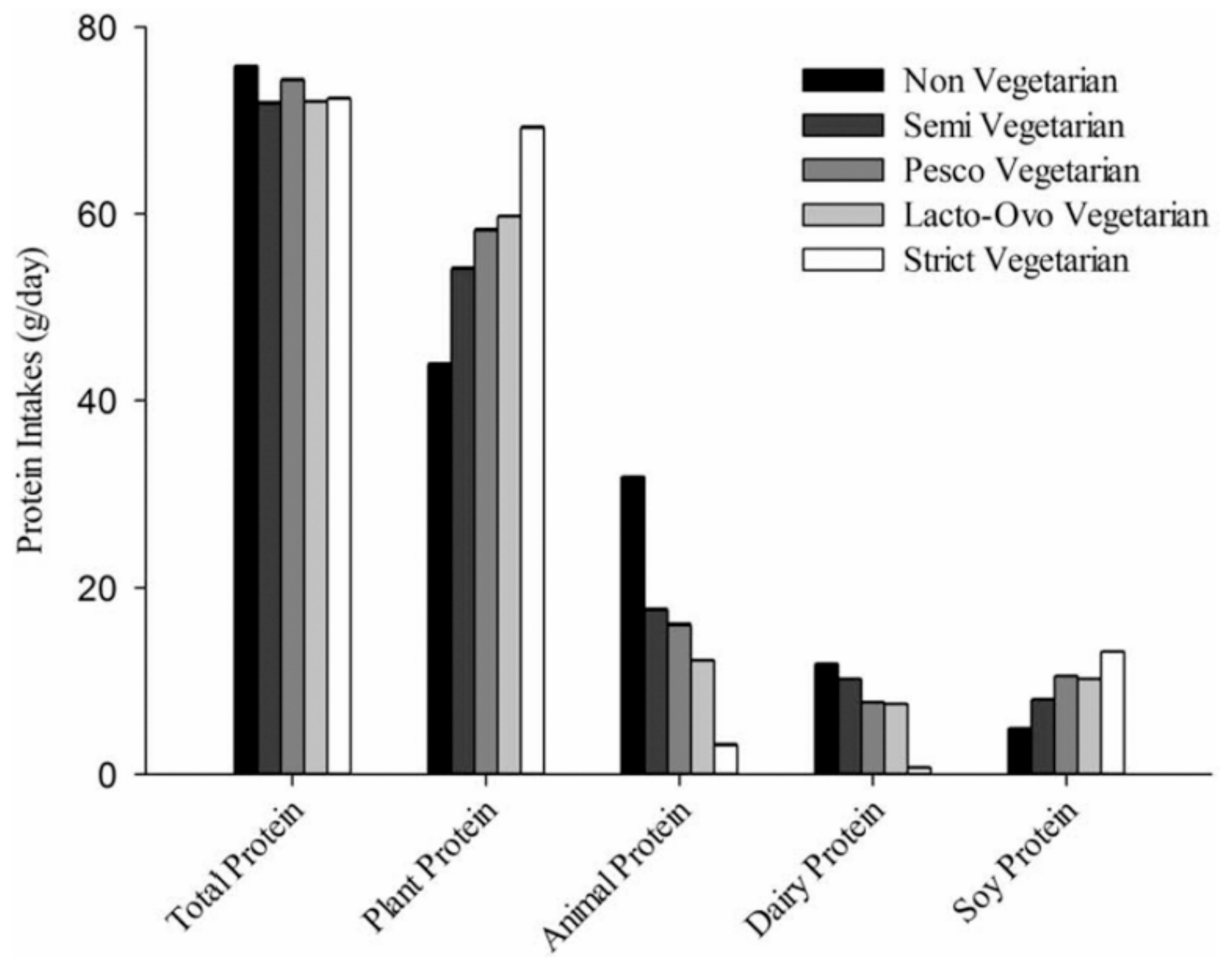

Protein Intake from Vegetarian Diets

2. Overall Protein Adequacy in Vegetarian Diets

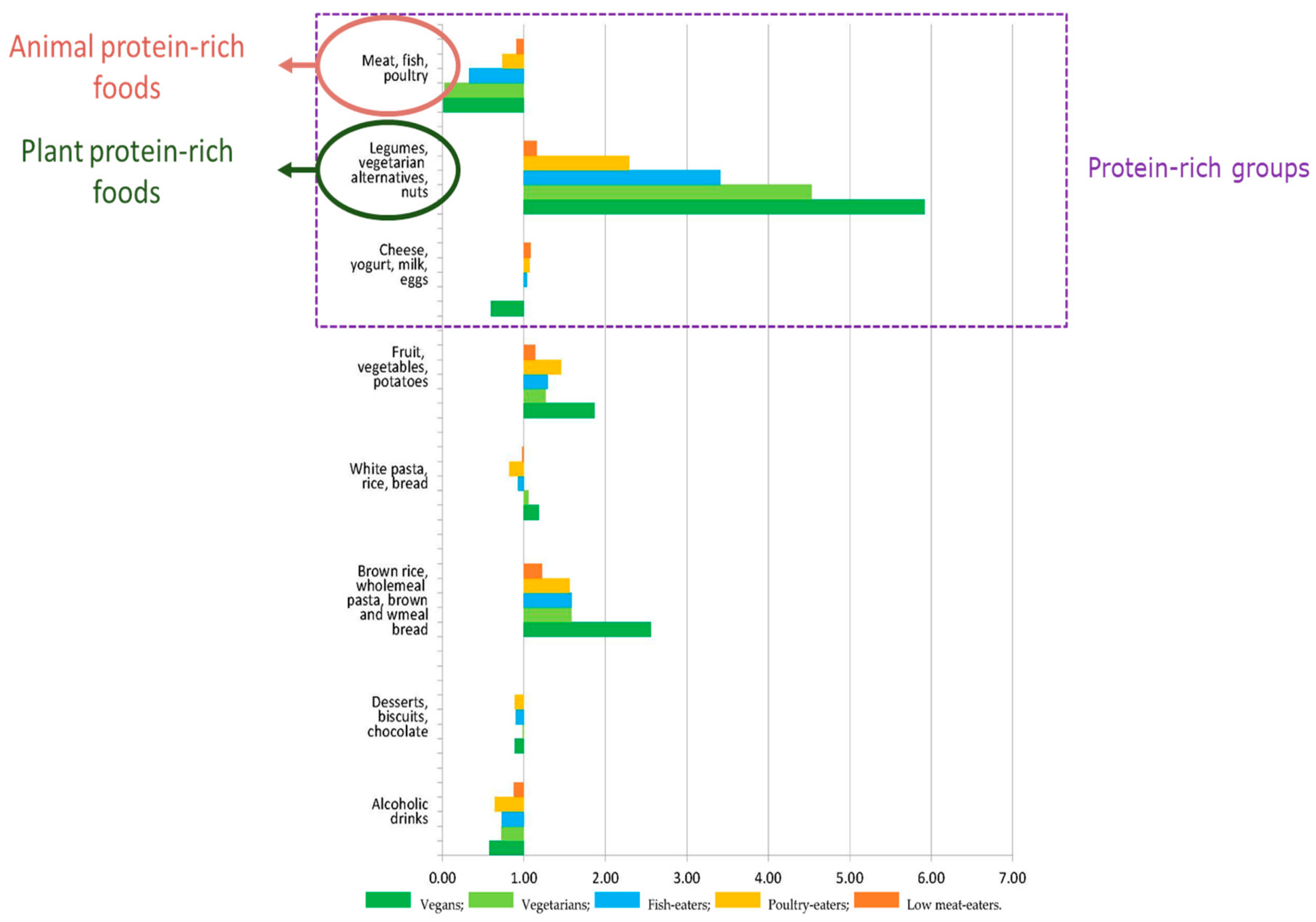

Limitations when Estimating Protein Inadequacy from Dietary Intake Surveys

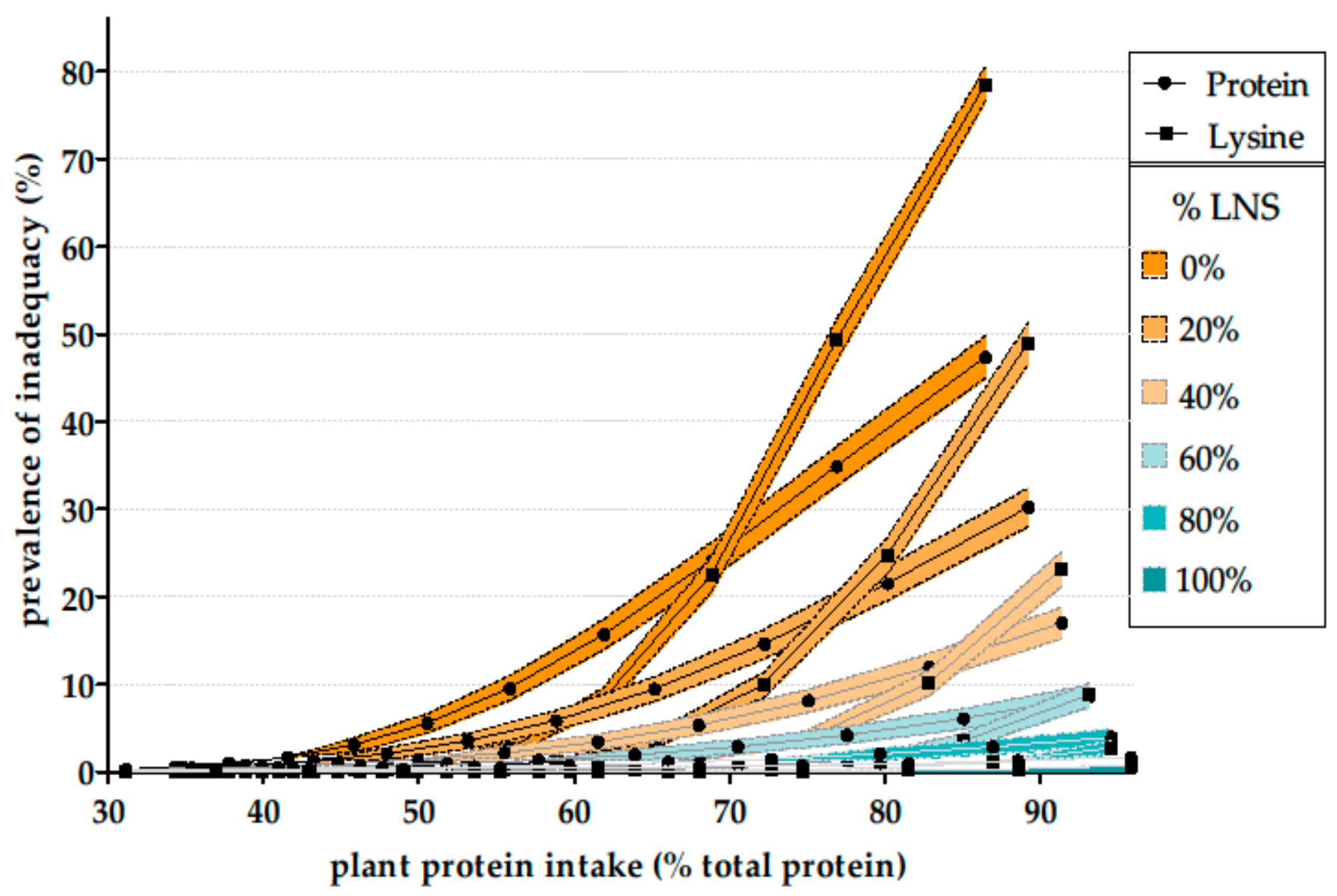

3. Amino Acid Adequacy in Vegetarian Diets

4. There Is No Evidence of Protein Deficiency among Vegetarians in Western Countries

5. Plant Protein Sources in Classic Vegetarian Diets and Lessons Regarding Future Trends towards Vegetarian Diets

6. The Case of Specific Issues in Specific Populations

6.1. Older People

6.2. Children

7. Nutrient Adequacy of Vegetarian Diets

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dagnelie, P.C.; Mariotti, F. Vegetarian diets: Definitions and pitfalls in interpreting literature on health effects of vegetarianism. In Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention; Mariotti, F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.; Simpson, I. Are we Eating Less Meat? A British Social Attitudes Report; NatCen Social Research: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tavoularis, G.; Sauvage, E. Les Nouvelles Générations Transforment la Consommation de Viande; Centre de Recherche pour l’Étude et l’Observation des Conditions de Vie: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Gavelle, E.; Davidenko, O.; Fouillet, H.; Delarue, J.; Darcel, N.; Huneau, J.F.; Mariotti, F. Self-Declared attitudes and beliefs regarding protein sources are a good prediction of the degree of transition to a low-meat diet in France. Appetite 2019, 142, 104345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobiecki, J.G.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Key, T.J. High compliance with dietary recommendations in a cohort of meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians, and vegans: Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Oxford study. Nutr. Res. 2016, 36, 464–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alles, B.; Baudry, J.; Mejean, C.; Touvier, M.; Peneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of sociodemographic and nutritional characteristics between self-reported vegetarians, vegans, and meat-eaters from the NutriNet-Sante Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade, J.E.; Burley, V.J.; Greenwood, D.C.; UK Women’s Cohort Study Steering Group. The UK Women’s Cohort Study: Comparison of vegetarians, fish-eaters and meat-eaters. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, B.; Larson, B.T.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Rainville, A.J.; Liepa, G.U. A vegetarian dietary pattern as a nutrient-dense approach to weight management: An analysis of the national health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2004. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, N.S.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabate, J.; Fraser, G.E. Nutrient profiles of vegetarian and nonvegetarian dietary patterns. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 1610–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkjaer, J.; Olsen, A.; Bjerregaard, L.J.; Deharveng, G.; Tjonneland, A.; Welch, A.A.; Crowe, F.L.; Wirfalt, E.; Hellstrom, V.; Niravong, M.; et al. Intake of total, animal and plant proteins, and their food sources in 10 countries in the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, S16–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilleri, G.M.; Verger, E.O.; Huneau, J.F.; Carpentier, F.; Dubuisson, C.; Mariotti, F. Plant and animal protein intakes are differently associated with nutrient adequacy of the diet of French adults. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 1466–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, C.M.; Egnell, M.; Huneau, J.F.; Mariotti, F. Plant protein intake and dietary diversity are independently associated with nutrient adequacy in French adults. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2351–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segovia-Siapco, G.; Sabate, J. Health and sustainability outcomes of vegetarian dietary patterns: A revisit of the EPIC-Oxford and the adventist health study-2 cohorts. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail (Anses). ANSES’s Opinion and Report on the Updating of the PNNS Guidelines: Revision of the Food-Based Dietary Guidelines; Anses: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://www.anses.fr/en/system/files/NUT2012SA0103Ra-1EN.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- McGill, C.R.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Devareddy, L. Ten-year trends in fiber and whole grain intakes and food sources for the United States population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2010. Nutrients 2015, 7, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO/FAO. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42665/WHO_TRS_916.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Popkin, B.M. Global nutrition dynamics: the world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistics Division. Food Balance Sheets. Available online: http://faostat3.fao.org/download/FB/*/E (accessed on 3 February 2017).

- Dubuisson, C.; Lioret, S.; Touvier, M.; Dufour, A.; Calamassi-Tran, G.; Volatier, J.L.; Lafay, L. Trends in food and nutritional intakes of French adults from 1999 to 2007: Results from the INCA surveys. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmadfa, I. (Ed.) European Nutrition and Health Report 2009; Karger: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd. Current protein intake in America: Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003–2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1554S–1557S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French Food Safety Agency (AFSSA). Report "Protein Intake: Dietary Intake, Quality, Requirements and Recommendations"; AFSSA: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition. Available online: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (accessed on 10 November 2017).

- Schmidt, J.A.; Rinaldi, S.; Scalbert, A.; Ferrari, P.; Achaintre, D.; Gunter, M.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Key, T.J.; Travis, R.C. Plasma concentrations and intakes of amino acids in male meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans: A cross-sectional analysis in the EPIC-Oxford cohort. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarys, P.; Deliens, T.; Huybrechts, I.; Deriemaeker, P.; Vanaelst, B.; De Keyzer, W.; Hebbelinck, M.; Mullie, P. Comparison of nutritional quality of the vegan, vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian and omnivorous diet. Nutrients 2014, 6, 1318–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, N.B.; Madsen, M.L.; Hansen, T.H.; Allin, K.H.; Hoppe, C.; Fagt, S.; Lausten, M.S.; Gobel, R.J.; Vestergaard, H.; Hansen, T.; et al. Intake of macro- and micronutrients in Danish vegans. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroke, A.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Voss, S.; Moseneder, J.; Thielecke, F.; Noack, R.; Boeing, H. Validation of a self-administered food-frequency questionnaire administered in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Study: Comparison of energy, protein, and macronutrient intakes estimated with the doubly labeled water, urinary nitrogen, and repeated 24-h dietary recall methods. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.E.; Welch, A.A.; Bingham, S.A. Validation of dietary intakes measured by diet history against 24 h urinary nitrogen excretion and energy expenditure measured by the doubly-labelled water method in middle-aged women. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 83, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subar, A.F.; Kipnis, V.; Troiano, R.P.; Midthune, D.; Schoeller, D.A.; Bingham, S.; Sharbaugh, C.O.; Trabulsi, J.; Runswick, S.; Ballard-Barbash, R.; et al. Using intake biomarkers to evaluate the extent of dietary misreporting in a large sample of adults: The OPEN study. Am. J. Epidemiol 2003, 158, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, C.L.; Westerterp, K.R.; Johansson, G.K. Validity of reported energy expenditure and energy and protein intakes in Swedish adolescent vegans and omnivores. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, L.S.; Midthune, D.; Carroll, R.J.; Krebs-Smith, S.; Subar, A.F.; Troiano, R.P.; Dodd, K.; Schatzkin, A.; Bingham, S.A.; Ferrari, P.; et al. Adjustments to improve the estimation of usual dietary intake distributions in the population. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 1836–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carriquiry, A.L. Estimation of usual intake distributions of nutrients and foods. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 601S–608S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, C.D.; Hartle, J.C.; Garrett, R.D.; Offringa, L.C.; Wasserman, A.S. Maximizing the intersection of human health and the health of the environment with regard to the amount and type of protein produced and consumed in the United States. Nutr. Rev. 2019, 77, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhaes, V.; Severo, M.; Torres, D.; Ramos, E.; Lopes, C.; by IAN-AF Consortium. Characterizing energy intake misreporting and its effects on intake estimations, in the Portuguese adult population. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millward, D.J.; Garnett, T. Plenary lecture 3: Food and the planet. Nutritional dilemmas of greenhouse gas emission reductions through reduced intakes of meat and dairy foods. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2010, 69, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boye, J.; Wijesinha-Bettoni, R.; Burlingame, B. Protein quality evaluation twenty years after the introduction of the protein digestibility corrected amino acid score method. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S183–S211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F. Plant protein, animal protein, and protein quality. In Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention; Mariotti, F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 621–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melina, V.; Craig, W.; Levin, S. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian diets. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1970–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO/UNU. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation (2002: Geneva, Switzerland). World Health Organization; WHO Technical Report Series, No 935; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, W.M.; Pellett, P.L.; Young, V.R. Meta-Analysis of nitrogen balance studies for estimating protein requirements in healthy adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, C.; Baroni, L.; Bertini, I.; Ciappellano, S.; Fabbri, A.; Papa, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Sbarbati, R.; Scarino, M.L.; Siani, V.; et al. Position paper on vegetarian diets from the working group of the Italian Society of Human Nutrition. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R.; American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: Vegetarian diets. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1266–1282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caso, G.; Scalfi, L.; Marra, M.; Covino, A.; Muscaritoli, M.; McNurlan, M.A.; Garlick, P.J.; Contaldo, F. Albumin synthesis is diminished in men consuming a predominantly vegetarian diet. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Lombard, K.A.; Olson, A.L.; Nelson, S.E.; Rebouche, C.J. Carnitine status of lactoovovegetarians and strict vegetarian adults and children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 50, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, E.H.; Berk, L.S.; Kettering, J.D.; Hubbard, R.W.; Peters, W.R. Dietary intake and biochemical, hematologic, and immune status of vegans compared with nonvegetarians. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 586S–593S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghighatdoost, F.; Bellissimo, N.; Totosy de Zepetnek, J.O.; Rouhani, M.H. Association of vegetarian diet with inflammatory biomarkers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 2713–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craddock, J.C.; Neale, E.P.; Peoples, G.E.; Probst, Y.C. Vegetarian-Based dietary patterns and their relation with inflammatory and immune biomarkers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirone, L. Blood findings in men on a diet devoid of meat and low in animal protein. Science 1950, 111, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A. Protein and Amino Acid Nutrition; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, S.; Burd, N.A.; van Loon, L.J. The skeletal muscle anabolic response to plant- versus animal-based protein consumption. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 1981–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorissen, S.H.M.; Crombag, J.J.R.; Senden, J.M.G.; Waterval, W.A.H.; Bierau, J.; Verdijk, L.B.; van Loon, L.J.C. Protein content and amino acid composition of commercially available plant-based protein isolates. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F.; Pueyo, M.E.; Tome, D.; Berot, S.; Benamouzig, R.; Mahe, S. The influence of the albumin fraction on the bioavailability and postprandial utilization of pea protein given selectively to humans. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, D.J.; Fereday, A.; Gibson, N.R.; Pacy, P.J. Human adult amino acid requirements: [1-13C]leucine balance evaluation of the efficiency of utilization and apparent requirements for wheat protein and lysine compared with those for milk protein in healthy adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, V.R.; Pellett, P.L. Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 59, 1203S–1212S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.P.; Tilton, K.S.; Ryland, L.L. Utilization of a delayed lysine or tryptophan supplement for protein repletion of rats. J. Nutr. 1968, 94, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millward, D.J. Amino acid scoring patterns for protein quality assessment. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S31–S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gavelle, E.; Huneau, J.F.; Bianchi, C.M.; Verger, E.O.; Mariotti, F. Protein adequacy is primarily a matter of protein quantity, not quality: Modeling an increase in plant:animal protein ratio in french adults. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannemans, D.L.; Wagenmakers, A.J.; Westerterp, K.R.; Schaafsma, G.; Halliday, D. Effect of protein source and quantity on protein metabolism in elderly women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 1228–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Adlercreutz, H. Relationship between animal protein intake and muscle mass index in healthy women. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlich, M.J.; Jaceldo-Siegl, K.; Sabate, J.; Fan, J.; Singh, P.N.; Fraser, G.E. Patterns of food consumption among vegetarians and non-vegetarians. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 112, 1644–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, K.E.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Key, T.J. Dietary intake of high-protein foods and other major foods in meat-eaters, poultry-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians, and vegans in UK biobank. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papier, K.; Tong, T.Y.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Fensom, G.K.; Knuppel, A.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J. Comparison of major protein-source foods and other food groups in meat-eaters and non-meat-eaters in the EPIC-Oxford cohort. Nutrients 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, D.C.; Cade, J.E.; Draper, A.; Barrett, J.H.; Calvert, C.; Greenhalgh, A. Seven unique food consumption patterns identified among women in the UK Women’s cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, J.A.; Chevalier, S.; Gougeon, R. Protein turnover and requirements in the healthy and frail elderly. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2006, 10, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mariotti, F. Protein intake throughout life and current dietary recommendations. In The Molecular Nutrition of Amino Acids and Proteins; Dardevet, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deutz, N.E.; Bauer, J.M.; Barazzoni, R.; Biolo, G.; Boirie, Y.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Krznaric, Z.; Nair, K.S.; et al. Protein intake and exercise for optimal muscle function with aging: Recommendations from the ESPEN Expert Group. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, A.N.; Cederholm, T. Health effects of protein intake in healthy elderly populations: A systematic literature review. Food Nutr. Res. 2014, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berner, L.A.; Becker, G.; Wise, M.; Doi, J. Characterization of dietary protein among older adults in the United States: Amount, animal sources, and meal patterns. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 113, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieland, M.; Borgonjen-Van den Berg, K.J.; van Loon, L.J.; de Groot, L.C. Dietary protein intake in community-dwelling, frail, and institutionalized elderly people: Scope for improvement. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddon-Jones, D.; Leidy, H. Dietary protein and muscle in older persons. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2014, 17, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, N.R. Protein-Centric meals for optimal protein utilization: Can it be that simple? J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 797–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, M.A.; Mosoni, L.; Boirie, Y.; Houlier, M.L.; Morin, L.; Verdier, E.; Ritz, P.; Antoine, J.M.; Prugnaud, J.; Beaufrere, B.; et al. Protein pulse feeding improves protein retention in elderly women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, M.A.; Mosoni, L.; Boirie, Y.; Houlier, M.L.; Morin, L.; Verdier, E.; Ritz, P.; Antoine, J.M.; Prugnaud, J.; Beaufrere, B.; et al. Protein feeding pattern does not affect protein retention in young women. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1700–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamerow, M.M.; Mettler, J.A.; English, K.L.; Casperson, S.L.; Arentson-Lantz, E.; Sheffield-Moore, M.; Layman, D.K.; Paddon-Jones, D. Dietary protein distribution positively influences 24-h muscle protein synthesis in healthy adults. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddon-Jones, D.; Rasmussen, B.B. Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2009, 12, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardevet, D.; Remond, D.; Peyron, M.A.; Papet, I.; Savary-Auzeloux, I.; Mosoni, L. Muscle wasting and resistance of muscle anabolism: The ‘anabolic threshold concept’ for adapted nutritional strategies during sarcopenia. Sci. World J. 2012, 269531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loenneke, J.P.; Loprinzi, P.D.; Murphy, C.H.; Phillips, S.M. Per meal dose and frequency of protein consumption is associated with lean mass and muscle performance. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 1506–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsijani, S.; Payette, H.; Morais, J.A.; Shatenstein, B.; Gaudreau, P.; Chevalier, S. Even mealtime distribution of protein intake is associated with greater muscle strength, but not with 3-y physical function decline, in free-living older adults: The Quebec longitudinal study on nutrition as a determinant of successful aging (NuAge study). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsijani, S.; Morais, J.A.; Payette, H.; Gaudreau, P.; Shatenstein, B.; Gray-Donald, K.; Chevalier, S. Relation between mealtime distribution of protein intake and lean mass loss in free-living older adults of the NuAge study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryson, C.; Walrand, S.; Giraudet, C.; Rousset, P.; Migne, C.; Bonhomme, C.; Le Ruyet, P.; Boirie, Y. ‘Fast proteins’ with a unique essential amino acid content as an optimal nutrition in the elderly: Growing evidence. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magne, H.; Savary-Auzeloux, I.; Migne, C.; Peyron, M.A.; Combaret, L.; Remond, D.; Dardevet, D. Contrarily to whey and high protein diets, dietary free leucine supplementation cannot reverse the lack of recovery of muscle mass after prolonged immobilization during ageing. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 2035–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardevet, D.; Sornet, C.; Bayle, G.; Prugnaud, J.; Pouyet, C.; Grizard, J. Postprandial stimulation of muscle protein synthesis in old rats can be restored by a leucine-supplemented meal. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonnie, M.; Hooker, E.; Brunstrom, J.M.; Corfe, B.M.; Green, M.A.; Watson, A.W.; Williams, E.A.; Stevenson, E.J.; Penson, S.; Johnstone, A.M. Protein for life: Review of optimal protein intake, sustainable dietary sources and the effect on appetite in ageing adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tieland, M.; Borgonjen-Van den Berg, K.J.; Van Loon, L.J.; de Groot, L.C. Dietary protein intake in Dutch elderly people: A focus on protein sources. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9697–9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paddon-Jones, D.; Campbell, W.W.; Jacques, P.F.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Moore, L.L.; Rodriguez, N.R.; van Loon, L.J. Protein and healthy aging. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrazaga, I.; Micard, V.; Gueugneau, M.; Walrand, S. The role of the anabolic properties of plant- versus animal-based protein sources in supporting muscle mass maintenance: A critical review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorissen, S.H.M.; Witard, O.C. Characterising the muscle anabolic potential of dairy, meat and plant-based protein sources in older adults. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2018, 77, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tieland, M.; Franssen, R.; Dullemeijer, C.; van Dronkelaar, C.; Kyung Kim, H.; Ispoglou, T.; Zhu, K.; Prince, R.L.; van Loon, L.J.C.; de Groot, L. The impact of dietary protein or amino acid supplementation on muscle mass and strength in elderly people: Individual participant data and meta-analysis of RCT’s. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, D.K.; Nicklas, B.J.; Ding, J.; Harris, T.B.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Newman, A.B.; Lee, J.S.; Sahyoun, N.R.; Visser, M.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; et al. Dietary protein intake is associated with lean mass change in older, community-dwelling adults: The Health, Aging, And Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.; Leung, J.; Woo, J.; Kwok, T. Associations of dietary protein intake on subsequent decline in muscle mass and physical functions over four years in ambulant older Chinese people. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2014, 18, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, C.K.; Ankarfeldt, M.Z.; Capra, S.; Bauer, J.; Raymond, K.; Heitmann, B.L. Lean body mass change over 6 years is associated with dietary leucine intake in an older Danish population. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 1556–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verreijen, A.M.; Engberink, M.F.; Houston, D.K.; Brouwer, I.A.; Cawthon, P.M.; Newman, A.B.; Tylavsky, F.A.; Harris, T.B.; Weijs, P.J.M.; Visser, M. Dietary protein intake is not associated with 5-y change in mid-thigh muscle cross-sectional area by computed tomography in older adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, V.R. Nutrient interactions with reference to amino acid and protein metabolism in non-ruminants; particular emphasis on protein-energy relations in man. Z. Ernahrungswiss 1991, 30, 239–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de L’alimentation, de L’environnement et du Travail (Anses). Avis et Rapport de l’Anses Relatifs à l’ “Actualisation des Repères du PNNS: Élaboration des Références Nutritionnelles”; Anses: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Panel on dietetic products nutrition and allergies. Scientific opinion on dietary reference values for protein. EFSA J. 2012, 10, 2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO/UNU. Energy and Protein Requirements. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. World Health Organization; WHO Technical Report Series, No 724; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Mazzocchi, A.; Bettocchi, S.; Agostoni, C. Vegetarian infants and complementary feeding. In Vegetarian and Plant-Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention; Mariotti, F., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavelle, E.; Huneau, J.F.; Mariotti, F. Patterns of protein food intake are associated with nutrient adequacy in the general French adult population. Nutrients 2018, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.M.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Heaney, R.P.; Nicklas, T.A.; Slavin, J.L.; Weaver, C.M. Commonly consumed protein foods contribute to nutrient intake, diet quality, and nutrient adequacy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, D.L.; Doughty, K.N.; Geagan, K.; Jenkins, D.A.; Gardner, C.D. Perspective: The public health case for modernizing the definition of protein quality. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Fung, T.T.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Longo, V.D.; Chan, A.T.; Giovannucci, E.L. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharrey, M.; Mariotti, F.; Mashchak, A.; Barbillon, P.; Delattre, M.; Fraser, G.E. Patterns of plant and animal protein intake are strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality: The adventist health study-2 cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, R.; Han, T.; Sun, C.; Na, L. Dietary protein consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Scott, D.; Hodge, A.M.; English, D.R.; Giles, G.G.; Ebeling, P.R.; Sanders, K.M. Dietary protein intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study and a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1352–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F. Animal and plant protein sources and cardiometabolic health. Adv. Nutr. in press.

- Mariotti, F.; Huneau, J.F. Plant and animal protein intakes are differentially associated with large clusters of nutrient intake that may explain part of their complex relation with CVD risk. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 559–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharrey, M.; Mariotti, F.; Mashchak, A.; Barbillon, P.; Delattre, M.; Huneau, J.F.; Fraser, G.E. Patterns of amino acids intake are strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality, independently of the sources of protein. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Meat-Eaters | Fish-Eaters | Lacto-ovo-Vegetarians | Vegans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 18,244 (60) | 4531 (15) | 6673 (22) | 803 (3) |

| Energy (kcal) | 2091 | 2030 | 2002 | 1944 |

| % Energy from protein | 17.2 | 15.5 | 14.0 | 13.1 |

| Protein (g/kg of body weight) 1 | 1.28 | 1.17 | 1.04 | 0.99 |

| Protein (g) 2 | 90 | 79 | 70 | 64 |

| Body weight (kg) 2 | 70 | 67 | 67 | 64 |

| Meat-Eaters | Neither Meat-Eaters nor Vegan | Vegans | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 90,664 (96.6) | 2370 (2.5) | 789 (0.8) |

| Energy (kcal) | 1899 | 1814 | 1877 |

| % Energy from protein | 17.6 | 14.2 | 12.8 |

| Protein (g) 1 | 84 | 64 | 60 |

| Study | Protein Intake | Vegans (n) | Method | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %E | g | g/kg bw | ||||

| EPIC-Oxford (UK) | 13.1 | 64 1 | 0.99 | 803 | FFQ 2 | [5,24] |

| Nutrinet (France) | 12.8 | 62 | 789 | Multiple 24-h R | [6] | |

| AHS-2 (North America) | 14.1 | 71 | 5694 | FFQ | [9] | |

| A Belgian study | 14 | 82 | 102 | FFQ | [25] | |

| A Danish Survey | 11.1 1 | 67 | 70 | 4-d weighted Record | [26] | |

| Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) | >10 (approx.) | 50 (approx.) | 0.83 (exactly) | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mariotti, F.; Gardner, C.D. Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112661

Mariotti F, Gardner CD. Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review. Nutrients. 2019; 11(11):2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112661

Chicago/Turabian StyleMariotti, François, and Christopher D. Gardner. 2019. "Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review" Nutrients 11, no. 11: 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112661

APA StyleMariotti, F., & Gardner, C. D. (2019). Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review. Nutrients, 11(11), 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112661