Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss

Abstract

1. Introduction

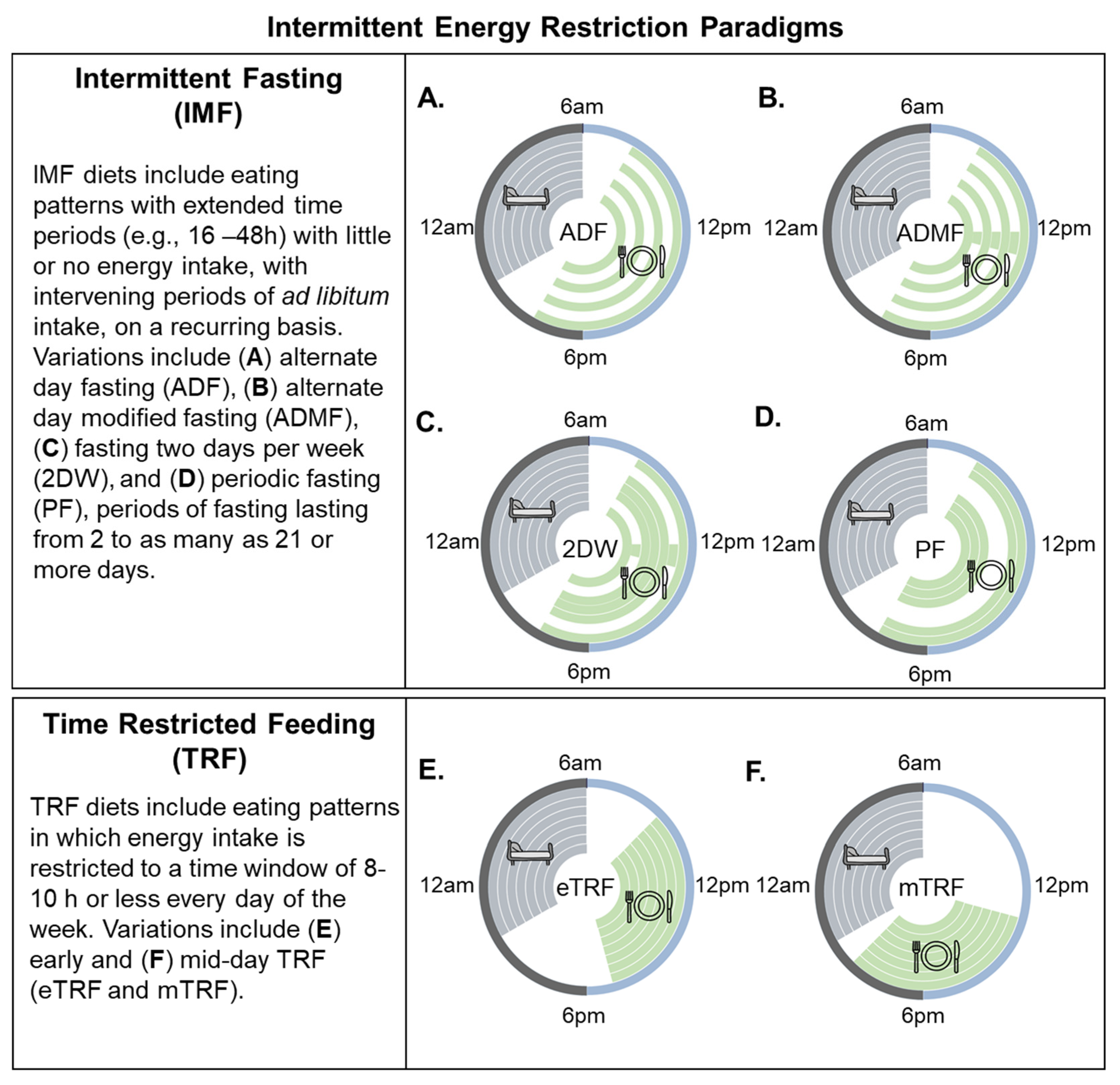

2. Intermittent Energy Restriction (IER) Strategies Defined

3. Effects of IMF on Body Weight, Body Composition, and Metabolic Outcomes: Evidence from Preclinical Studies

4. Effects of TRF on Body Weight, Body Composition, and Metabolic Outcomes: Evidence from Preclinical Studies

5. Current Evidence for IMF as a Weight Loss Strategy: Evidence from Humans? Clinical Studies

6. Current Evidence for TRF as a Weight Loss Strategy: Evidence from Humans? Clinical Studies

7. Are the Metabolic Benefits of IMF and TRF in Clinical Studies Solely Due to Caloric Restriction and Weight Loss?

8. Limitations of Previous Clinical Studies and Evidence Gaps

9. Future Directions and Outstanding Questions

9.1. Is IMF a Durable Weight Loss Strategy?

9.2. Can We Predict Who Will Be Successful on an IMF or TRF Diet Compared to CER?

9.3. Is TRF Alone a Durable Weight Loss Strategy and does TRF Enhance Weight Loss When Combined with CER?

9.4. How Do IMF and TRF Impact Components of Energy Balance and Macronutrient Oxidation in Humans?

9.5. How Do We Define Meal Timing and What Is the Optimal Eating Window in Studies of TRF?

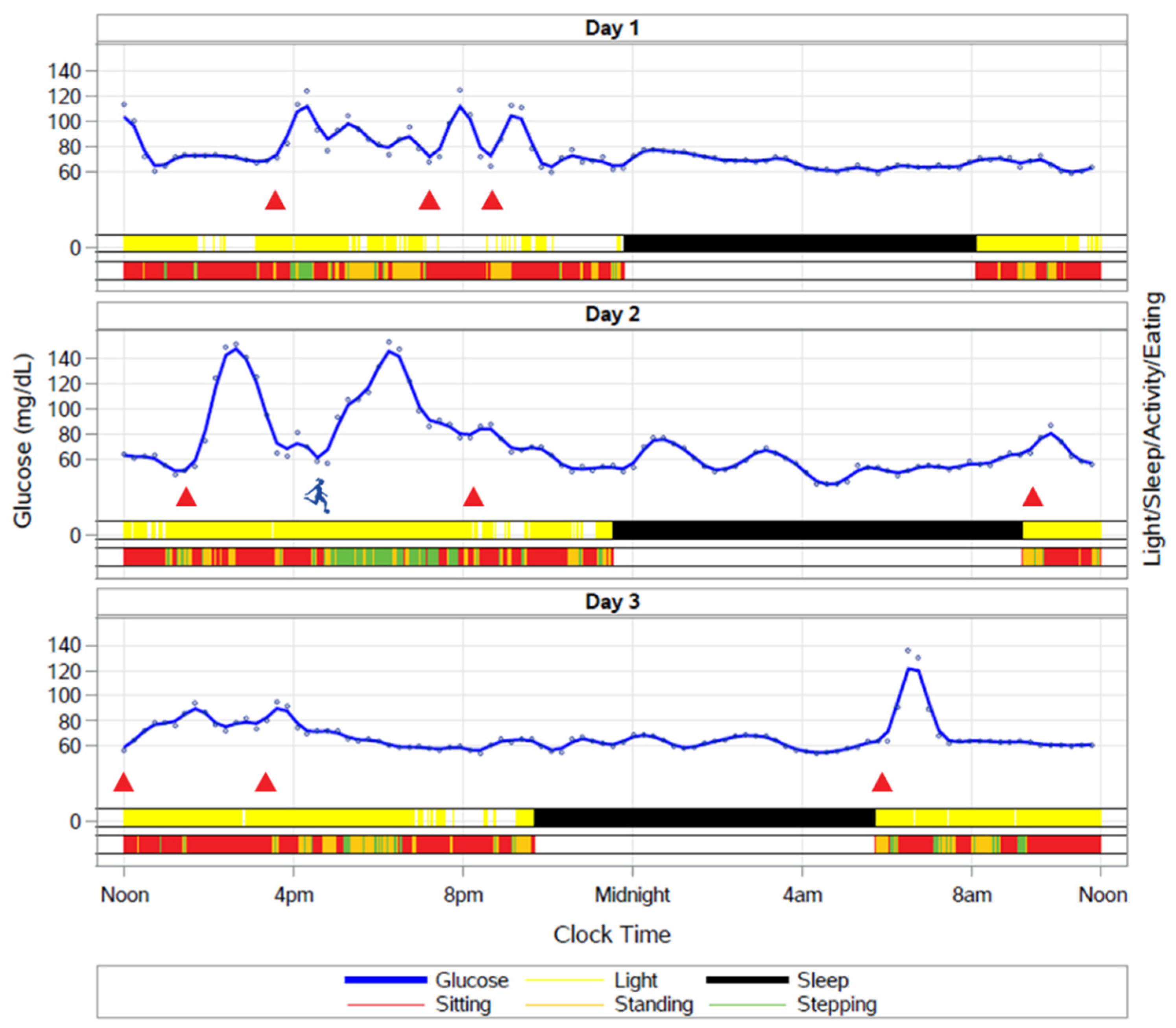

9.6. How Do Fasting and the Timing of Meals Impact the Temporal Organization of Behaviors such as Sleep and Activity across the 24 h Cycle?

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Kit, B.K.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014, 311, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Fiebelkorn, I.C.; Wang, G. National medical spending attributable to overweight and obesity: How much, and who’s paying? Health Aff. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julia, C.; Peneau, S.; Andreeva, V.A.; Mejean, C.; Fezeu, L.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S. Weight-loss strategies used by the general population: How are they perceived? PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014, 129, S102–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbridge, E.A.; Prendergast, L.A.; Pritchard, J.E.; Proietto, J. One-year weight maintenance after significant weight loss in healthy overweight and obese subjects: Does diet composition matter? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naude, C.E.; Schoonees, A.; Senekal, M.; Young, T.; Garner, P.; Volmink, J. Low carbohydrate versus isoenergetic balanced diets for reducing weight and cardiovascular risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombrowski, S.U.; Knittle, K.; Avenell, A.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Sniehotta, F.F. Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2014, 348, g2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, D.K.; Chen, M.; Manson, J.E.; Ludwig, D.S.; Willett, W.; Hu, F.B. Effect of low-fat diet interventions versus other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 968–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B.C.; Kanters, S.; Bandayrel, K.; Wu, P.; Naji, F.; Siemieniuk, R.A.; Ball, G.D.; Busse, J.W.; Thorlund, K.; Guyatt, G.; et al. Comparison of weight loss among named diet programs in overweight and obese adults: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2014, 312, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, G.D.; Wyatt, H.R.; Hill, J.O.; Makris, A.P.; Rosenbaum, D.L.; Brill, C.; Stein, R.I.; Mohammed, B.S.; Miller, B.; Rader, D.J.; et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 153, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansinger, M.L.; Gleason, J.A.; Griffith, J.L.; Selker, H.P.; Schaefer, E.J. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction: A randomized trial. JAMA 2005, 293, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.W.; Konz, E.C.; Frederich, R.C.; Wood, C.L. Long-term weight-loss maintenance: A meta-analysis of US studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franz, M.J.; VanWormer, J.J.; Crain, A.L.; Boucher, J.L.; Histon, T.; Caplan, W.; Bowman, J.D.; Pronk, N.P. Weight-loss outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, P.S.; Wing, R.R.; Davidson, T.; Epstein, L.; Goodpaster, B.; Hall, K.D.; Levin, B.E.; Perri, M.G.; Rolls, B.J.; Rosenbaum, M.; et al. NIH working group report: Innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity 2015, 23, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P.; Longo, V.D.; Harvie, M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 39, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, R. Intermittent fasting: The next big weight loss fad. CMAJ 2013, 185, E321–E322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, A. Fasting for weight loss: An effective strategy or latest dieting trend? Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, R.E.; Laughlin, G.A.; LaCroix, A.Z.; Hartman, S.J.; Natarajan, L.; Senger, C.M.; Martinez, M.E.; Villasenor, A.; Sears, D.D.; Marinac, C.R.; et al. Intermittent Fasting and Human Metabolic Health. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, S.D.; Moehl, K.; Donahoo, W.T.; Marosi, K.; Lee, S.A.; Mainous, A.G., 3rd; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Mattson, M.P. Flipping the Metabolic Switch: Understanding and Applying the Health Benefits of Fasting. Obesity 2018, 26, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, A.; Zarrinpar, A.; Miu, P.; Panda, S. Time-restricted feeding is a preventative and therapeutic intervention against diverse nutritional challenges. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 991–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, A.; Lin, T.; Le, H.D.; Chang, M.W.; Panda, S. Time-Restricted Feeding Prevents Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome in Mice Lacking a Circadian Clock. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 303–319.e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatori, M.; Vollmers, C.; Zarrinpar, A.; DiTacchio, L.; Bushong, E.A.; Gill, S.; Leblanc, M.; Chaix, A.; Joens, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.; et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempel, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Fitzgibbon, M.; Freels, S.; Varady, K.A. Dietary and physical activity adaptations to alternate day modified fasting: Implications for optimal weight loss. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempel, M.C.; Kroeger, C.M.; Varady, K.A. Alternate day fasting (ADF) with a high-fat diet produces similar weight loss and cardio-protection as ADF with a low-fat diet. Metabolism 2013, 62, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catenacci, V.A.; Pan, Z.; Ostendorf, D.; Brannon, S.; Gozansky, W.S.; Mattson, M.P.; Martin, B.; MacLean, P.S.; Melanson, E.L.; Troy Donahoo, W. A randomized pilot study comparing zero-calorie alternate-day fasting to daily caloric restriction in adults with obesity. Obesity 2016, 24, 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, A.M.; Faber, P.; Gibney, E.R.; Elia, M.; Horgan, G.; Golden, B.E.; Stubbs, R.J. Effect of an acute fast on energy compensation and feeding behaviour in lean men and women. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 2002, 26, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, R.; Johnston, K.L.; Collins, A.L.; Robertson, M.D. Investigation into the acute effects of total and partial energy restriction on postprandial metabolism among overweight/obese participants. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, B.D.; Muhlestein, J.B.; Anderson, J.L. Health effects of intermittent fasting: Hormesis or harm? A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, S.; Klempel, M.C.; Kroeger, C.M.; Aggour, E.; Calvo, Y.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Hoddy, K.K.; Varady, K.A. Effect of exercising while fasting on eating behaviors and food intake. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2013, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoddy, K.K.; Gibbons, C.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Barnosky, A.; Bhutani, S.; Gabel, K.; Finlayson, G.; Varady, K.A. Changes in hunger and fullness in relation to gut peptides before and after 8 weeks of alternate day fasting. Clin. Nutr. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.B.; Summer, W.; Cutler, R.G.; Martin, B.; Hyun, D.H.; Dixit, V.D.; Pearson, M.; Nassar, M.; Telljohann, R.; Maudsley, S.; et al. Alternate day calorie restriction improves clinical findings and reduces markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in overweight adults with moderate asthma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 42, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Panda, S. A Smartphone App Reveals Erratic Diurnal Eating Patterns in Humans that Can Be Modulated for Health Benefits. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, D.E.; Wan, R.; Brown, M.; Cheng, A.; Wareski, P.; Abernethy, D.R.; Mattson, M.P. Caloric restriction and intermittent fasting alter spectral measures of heart rate and blood pressure variability in rats. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, R.M.; Guo, Z.; de Cabo, R.; Iyun, T.; Rios, M.; Hagepanos, A.; Ingram, D.K.; Lane, M.A.; Mattson, M.P. Intermittent fasting dissociates beneficial effects of dietary restriction on glucose metabolism and neuronal resistance to injury from calorie intake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 6216–6220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotthardt, J.D.; Verpeut, J.L.; Yeomans, B.L.; Yang, J.A.; Yasrebi, A.; Roepke, T.A.; Bello, N.T. Intermittent Fasting Promotes Fat Loss with Lean Mass Retention, Increased Hypothalamic Norepinephrine Content, and Increased Neuropeptide Y Gene Expression in Diet-Induced Obese Male Mice. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Rodriguez, V.A.; de Groot, M.H.M.; Rijo-Ferreira, F.; Green, C.B.; Takahashi, J.S. Mice under Caloric Restriction Self-Impose a Temporal Restriction of Food Intake as Revealed by an Automated Feeder System. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 267–277.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science 2016, 354, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaix, A.; Zarrinpar, A. The effects of time-restricted feeding on lipid metabolism and adiposity. Adipocyte 2015, 4, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinpar, A.; Chaix, A.; Yooseph, S.; Panda, S. Diet and feeding pattern affect the diurnal dynamics of the gut microbiome. Cell Metab 2014, 20, 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, M.N.; Pegington, M.; Mattson, M.P.; Frystyk, J.; Dillon, B.; Evans, G.; Cuzick, J.; Jebb, S.A.; Martin, B.; Cutler, R.G.; et al. The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers: A randomized trial in young overweight women. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 35, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvie, M.; Wright, C.; Pegington, M.; McMullan, D.; Mitchell, E.; Martin, B.; Cutler, R.G.; Evans, G.; Whiteside, S.; Maudsley, S.; et al. The effect of intermittent energy and carbohydrate restriction v. daily energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers in overweight women. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 1534–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, S.; Clifton, P.M.; Keogh, J.B. The effects of intermittent compared to continuous energy restriction on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes; a pragmatic pilot trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 122, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, S.; Clifton, P.M.; Keogh, J.B. Effect of Intermittent Compared with Continuous Energy Restricted Diet on Glycemic Control in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubel, R.; Nattenmuller, J.; Sookthai, D.; Nonnenmacher, T.; Graf, M.E.; Riedl, L.; Schlett, C.L.; von Stackelberg, O.; Johnson, T.; Nabers, D.; et al. Effects of intermittent and continuous calorie restriction on body weight and metabolism over 50 wk: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conley, M.; Le Fevre, L.; Haywood, C.; Proietto, J. Is two days of intermittent energy restriction per week a feasible weight loss approach in obese males? A randomised pilot study. Nutr. Diet 2018, 75, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundfor, T.M.; Svendsen, M.; Tonstad, S. Effect of intermittent versus continuous energy restriction on weight loss, maintenance and cardiometabolic risk: A randomized 1-year trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varady, K.A.; Bhutani, S.; Klempel, M.C.; Kroeger, C.M. Comparison of effects of diet versus exercise weight loss regimens on LDL and HDL particle size in obese adults. Lipids Health Dis. 2011, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Kroeger, C.M.; Barnosky, A.; Klempel, M.C.; Bhutani, S.; Hoddy, K.K.; Gabel, K.; Freels, S.; Rigdon, J.; Rood, J.; et al. Effect of Alternate-Day Fasting on Weight Loss, Weight Maintenance, and Cardioprotection Among Metabolically Healthy Obese Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, A.T.; Liu, B.; Wood, R.E.; Vincent, A.D.; Thompson, C.H.; O’Callaghan, N.J.; Wittert, G.A.; Heilbronn, L.K. Effects of Intermittent Versus Continuous Energy Intakes on Insulin Sensitivity and Metabolic Risk in Women with Overweight. Obesity 2019, 27, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trepanowski, J.F.; Kroeger, C.M.; Barnosky, A.; Klempel, M.; Bhutani, S.; Hoddy, K.K.; Rood, J.; Ravussin, E.; Varady, K.A. Effects of alternate-day fasting or daily calorie restriction on body composition, fat distribution, and circulating adipokines: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 1871–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Hamilton, S.; Azevedo, L.B.; Olajide, J.; De Brun, C.; Waller, G.; Whittaker, V.; Sharp, T.; Lean, M.; Hankey, C.; et al. Intermittent fasting interventions for treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2018, 16, 507–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.O.; Schlundt, D.G.; Sbrocco, T.; Sharp, T.; Pope-Cordle, J.; Stetson, B.; Kaler, M.; Heim, C. Evaluation of an alternating-calorie diet with and without exercise in the treatment of obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1989, 50, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viegener, B.J.; Renjilian, D.A.; McKelvey, W.F.; Schein, R.L.; Perri, M.G.; Nezu, A.M. Effects of an intermittent, low-fat, low-calorie diet in the behavioral treatment of obesity. Behav. Ther. 1990, 21, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.; Howell, A.; Morris, J.; Harvie, M. Intermittent energy restriction for weight loss: Spontaneous reduction of energy intake on unrestricted days. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 674–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowicz, D.; Barnea, M.; Wainstein, J.; Froy, O. High caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaulet, M.; Gomez-Abellan, P.; Alburquerque-Bejar, J.J.; Lee, Y.C.; Ordovas, J.M.; Scheer, F.A. Timing of food intake predicts weight loss effectiveness. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowden, A.; Moreno, C.; Holmback, U.; Lennernas, M.; Tucker, P. Eating and shift work—Effects on habits, metabolism and performance. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2010, 36, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHill, A.W.; Phillips, A.J.; Czeisler, C.A.; Keating, L.; Yee, K.; Barger, L.K.; Garaulet, M.; Scheer, F.A.; Klerman, E.B. Later circadian timing of food intake is associated with increased body fat. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Feng, W.; Wang, F.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Li, M.; Tse, G.; Vlaanderen, J.; Vermeulen, R.; Tse, L.A. Meta-analysis on shift work and risks of specific obesity types. Obes. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, K.; Hoddy, K.K.; Haggerty, N.; Song, J.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Panda, S.; Varady, K.A. Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot study. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2018, 4, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, R.; Robertson, T.; Robertson, M.; Johnston, J. A pilot feasibility study exploring the effects of a moderate time-restricted feeding intervention on energy intake, adiposity and metabolic physiology in free-living human subjects. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, K.; Kroeger, C.M.; Trepanowski, J.F.; Hoddy, K.K.; Cienfuegos, S.; Kalam, F.; Varady, K.A. Differential Effects of Alternate-Day Fasting Versus Daily Calorie Restriction on Insulin Resistance. Obesity 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, G. Effects of free fatty acids (FFA) on glucose metabolism: Significance for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2003, 111, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundfor, T.M.; Tonstad, S.; Svendsen, M. Effects of intermittent versus continuous energy restriction for weight loss on diet quality and eating behavior. A randomized trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, P.S.; Rothman, A.J.; Nicastro, H.L.; Czajkowski, S.M.; Agurs-Collins, T.; Rice, E.L.; Courcoulas, A.P.; Ryan, D.H.; Bessesen, D.H.; Loria, C.M. The Accumulating Data to Optimally Predict Obesity Treatment (ADOPT) Core Measures Project: Rationale and Approach. Obesity 2018, 26 (Suppl. 2), S6–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, L.A.; Nicastro, H.L.; Roberts, S.B.; Evans, M.; Jakicic, J.M.; Laposky, A.D.; Loria, C.M. Accumulating Data to Optimally Predict Obesity Treatment (ADOPT) Core Measures: Behavioral Domain. Obesity 2018, 26 (Suppl. 2), S16–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saelens, B.E.; Arteaga, S.S.; Berrigan, D.; Ballard, R.M.; Gorin, A.A.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Pratt, C.; Reedy, J.; Zenk, S.N. Accumulating Data to Optimally Predict Obesity Treatment (ADOPT) Core Measures: Environmental Domain. Obesity 2018, 26 (Suppl. 2), S35–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, A.R.; Boutelle, K.; Czajkowski, S.M.; Epel, E.S.; Green, P.A.; Hunter, C.M.; Rice, E.L.; Williams, D.M.; Young-Hyman, D.; Rothman, A.J. Accumulating Data to Optimally Predict Obesity Treatment (ADOPT) Core Measures: Psychosocial Domain. Obesity 2018, 26 (Suppl. 2), S45–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravussin, E.; Beyl, R.A.; Poggiogalle, E.; Hsia, D.S.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Reduces Appetite and Increases Fat Oxidation but Does Not Affect Energy Expenditure in Humans. Obesity 2019, 27, 1244–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHill, A.W.; Czeisler, C.A.; Phillips, A.J.K.; Keating, L.; Barger, L.K.; Garaulet, M.; Scheer, F.; Klerman, E.B. Caloric and Macronutrient Intake Differ with Circadian Phase and between Lean and Overweight Young Adults. Nutrients 2019, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Garaulet, M.; Scheer, F. Meal timing and obesity: Interactions with macronutrient intake and chronotype. Int. J. Obes. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo Munoz, J.S.; Gomez Gallego, M.; Diaz Soler, I.; Barbera Ortega, M.C.; Martinez Caceres, C.M.; Hernandez Morante, J.J. Effect of a chronotype-adjusted diet on weight loss effectiveness: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshed, H.; Beyl, R.A.; Della Manna, D.L.; Yang, E.S.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves 24-Hour Glucose Levels and Affects Markers of the Circadian Clock, Aging, and Autophagy in Humans. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.F.; Beyl, R.; Early, K.S.; Cefalu, W.T.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1212–1221.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, T.; Tinsley, G.; Bianco, A.; Marcolin, G.; Pacelli, Q.F.; Battaglia, G.; Palma, A.; Gentil, P.; Neri, M.; Paoli, A. Effects of eight weeks of time-restricted feeding (16/8) on basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors in resistance-trained males. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonsson, S.; Sewall, A.; Lidholm, H.; Hursti, T. The Meal Pattern Questionnaire: A psychometric evaluation using the Eating Disorder Examination. Eat. Behav. 2016, 21, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, K.C.; Lundgren, J.D.; O’Reardon, J.P.; Martino, N.S.; Sarwer, D.B.; Wadden, T.A.; Crosby, R.D.; Engel, S.G.; Stunkard, A.J. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): Psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the Night Eating Syndrome. Eat. Behav. 2008, 9, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashti, H.S.; Scheer, F.; Saxena, R.; Garaulet, M. Timing of Food Intake: Identifying Contributing Factors to Design Effective Interventions. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | N | Age b (Years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Intervention Duration | Analysis | Interventions | Weight Loss a | Attrition a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvie et al., 2011 [40] | 107 100% Female | 30–45 | 24–40 | 26 weeks | Intent-to-Treat | 2DW 25% overall energy restriction delivered as VLCD (25% estimated EI) on 2 consecutive days/week; no restriction on the other 5 days | 2DW = −6.4 ± 11.2 kg e | 2DW = 20.8% |

| CER 25% restriction below estimated requirements 7 days/week | CER = −5.6 ± 9.2 kg e | CER = 13% | ||||||

| Varady et al., 2011 [47] | 49 81.2% Female | 35–65 | 25–39.9 | 12 weeks | Completer | AMDF 25% of baseline EI on fast days (meals provided), ad libitum at home on fed days | ADMF = −5.2 ± 4.0% e | ADMF = 13.3% |

| CER 75% of baseline EI daily (meals provided) | CER = −5.0 ± 4.9% e | CER = 20% | ||||||

| Exercise Ad libitum during the entire study; engaged in moderate intensity exercise program 3 times/week | Exercise = −5.1 ± 3.1% e | Exercise = 20% | ||||||

| Control Ad libitum during the entire study | Control = −0.2 ± 1.4% e | Control = 20% | ||||||

| Harvie et al., 2013 [41] | 115 100% Female | 20–69b | 24–45 | 12 weeks | Intent-to-Treat | 2DW—Carbohydrate Restriction (CR) 30% EI of baseline energy requirements (high protein, moderate fat) with 40 g carbohydrate restriction on two consecutive days; eucaloric diet the other 5 days | 2DW CR = 79.4 (95%CI 74.6–84.1) kg to 74.4 (95%CI 70.0–78.9) kg | 2DW CR = 10.8% |

| 2DW—Carbohydrate Restriction + ad libitum Protein and Fat (CR+PF) 30% EI of baseline energy requirements and 40 g carbohydrate restriction with ad libitum protein and fat on two consecutive days; eucaloric diet the other 5 days | 2DW CR + PF = 82.4 (95%CI 77.2–87.6) kg to 77.6 (95%CI 72.9–82.4) kg | 2DW CR+PF = 18.4% | ||||||

| CER 75% EI of baseline energy requirements daily | DER = 86 (95%CI 80.6–91.3) kg to 82.3 (95%CI 77.1–87.5) kg | DER = 17.5% | ||||||

| Carter et al., 2016 [42] | 63 52.4% Female | ≥18 | ≥27 | 12 weeks | Completer | 2DW 1670–2500 kJ/day for 2 non-consecutive days each week, and 5 days of ad libitum intake | 2DW = −6.2 ± 3.6% | 2DW = 16.1% |

| CER Continuous energy restriction diet of 5000–6500 kJ/day | CER = −5.6 ± 4.4% | CER = 21.8% | ||||||

| Catenacci et al., 2016 [25] | 26 80% Female | 18–55 | ≥30 | 8 weeks | Completer | ADF 100% energy restriction on fasting day, ad libitum on fed days. Meals provided | ADF = −8.8 ± 3.7% e | ADF = 6.7% |

| CER ~1675 kJ deficit per day. Meals provided | CER = −6.2 ± 3.1% e | CER = 14.3% | ||||||

| Trepanowski et al., 2017 [48] | 100 84% Female | 18–64 | 25–40 | 26 weeks | Intent-to-Treat | ADMF 25% of baseline EI as lunch on fast days, 125% of baseline EI split between meals on fed days. Meals provided in first 3 months | ADMF = −6.8% (95%CI −9.1% to −4.5%) | ADF = 26.5% |

| CER 75% of baseline EI split between three meals daily. Meals provided in first 3 months | CER = −6.8% (95% CI −9.1% to −4.6%) | CER = 17.1% | ||||||

| Control No intervention; maintain baseline weight | As compared to control | Control = 19.4% | ||||||

| Carter et al., 2018 [43] | 137 56.2% Female | ≥18 | ≥27 | 52 weeks | Intent-to-Treat | 2DW 2100–2500 kJ/day for 2 non-consecutive days each week, and 5 days of habitual eating | 2DW = −6.8 ± 6.4 kg e (about −6.8%) c | 2DW = 28.6% |

| CER Continuous energy restriction diet of 5000–6300 kJ/day | CER = −5.0 ± 7.1 kg e (about −4.9%) c | CER = 31.3% | ||||||

| Conley et al., 2018 [45] | 24 0% Female | 55–75 | ≥30 | 26 weeks | Completer | 2DW Restrict calorie intake to ~2500 kJ on two non-consecutive days per week; ad libitum intake on remaining five days | 2DW = 5.3 ± 3.0 kg (5.5 ± 3.2%) | 2DW = 8.3% |

| CER Daily ~2100 kJ energy-restricted diet from average requirement | CER = 5.5 ± 4.3 kg (5.4 ± 4.2%) | CER = 0% | ||||||

| Schübel et al., 2018 [44] | 150 50% Female | 35–65 | 25–40 | 12 weeks | Intent-to-Treat | 2DW Restriction at 80% weekly as 2 non-consecutive days with 75% energy restriction 5 days with no restriction | 2DW = −7.1 ± 0.7% d | 2DW = 4.1% |

| CER Continuous energy restriction at 80% | CER = −5.2 ± 0.6% d | CER = 6.1% | ||||||

| Control No energy restriction | Control = −3.3 ± 0.6% d | Control = 1.9% | ||||||

| Sundfør et al., 2018 [46] | 112 50% female | 21–70 | 30–45 | 26 weeks | Intent-to-Treat | 2DW ~1700/2500 kJ (female/male) energy restriction on two non-consecutive fasting days; ad libitum energy intake on remaining 5 days | 2DW = −9.1 ± 5.0 kg (about −8.4%) c | 2DW = 1.9% |

| CER Daily restriction of energy to match IER groups | CER = −9.4 ± 5.3 kg (about −8.7%) c | CER = 3.4% | ||||||

| Hutchison et al., 2019 [49] | 88 100% Female | 35–70 | 25–42 | 10 weeks | Completer | ADMF 70 IF diet (32% EI on fast days and 100% EI on fed days) to equal 70% of calculated baseline energy requirements on three non-consecutive days per week | ADMF 70 = −5.4 ± 2.5 kg e (about −6.0%) c | ADMF 70 = 12% |

| ADMF 100 IF diet (37% of EI on fast days and 145% EI on fed days) to equal 100% of calculated baseline energy requirements on three non-consecutive days per week | ADMF 100 = −2.7 ± 2.5 kg e (about −3.2%) c | ADMF 100 = 12% | ||||||

| CER Continuous restriction at 70% of calculated baseline energy requirements daily | CER = −3.9 ± 2.0 kg e (about −4.4%) c | CER = 7.7% | ||||||

| Control 100% of calculated baseline requirements daily | Control = 0.4 ± 1.4 kg e (about 0.5%) c | Control = 8.3% |

| Reference | Participants & Interventions | Measurement Conditions | Glycemic Outcomes | Lipid Outcomes | Other Biomarker Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvie et al., 2011 [40] | -Pre-menopausal women who were overweight or obese -2DW; CER | -Overnight fast, at least 5 days after the last partial energy restriction day in the 2DW group -In a subset of the 2DW group (n = 15), fasting blood samples were collected after 5 days of normal intake on the morning after a partial energy restriction day and after 2 days of normal intake | -Glucose (ND) -Greater decrease in insulin and increase in insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR) in the 2DW group -Greater decreases in insulin sensitivity on the morning after a partial energy restriction day in a subset of the 2DW group | -Cholesterol (ND) -LDL (ND) -HDL (ND) -TGs (ND) | -CRP (ND) -Adiponectin (ND) -Leptin (ND) -Ketones (ND) |

| Varady et al., 2011 [47] | -Adults who were overweight or obese -ADMF; CER | 12 h fasting blood samples | Not assessed | -Cholesterol (ND) -LDL (ND) -HDL (ND) -Greater decrease in TGs in the ADMF group | Not assessed |

| Harvie et al., 2013 [41] | -Pre-menopausal women -2DW + Carbohydrate Restriction; 2DW + Carbohydrate restriction and ad libitum protein and fat restriction; CER | Overnight fast, at least 5 days after the weekly 2 day partial energy restriction day in the 2DW groups | -Greater decrease in insulin and increase in insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR) in the 2DW groups -HbA1c (ND) -Glucose (ND) | -Cholesterol (ND) -LDL (ND) -HDL (ND) -TGs (ND) | -IGF-1 (ND) -IL-6 (ND) -TNF-α (ND) -Ketones (ND) -Leptin (ND) -Adiponectin (ND) |

| Carter et al., 2016 [42] | -Adults with T2DM who were overweight or obese -2DW; CER | After an overnight fast (minimum of 8 h) | -HbA1c (ND) | Not assessed | Not assessed |

| Catenacci et al., 2016 [25] | -Adults who were overweight or obese -ADF; CER | After an overnight fast (minimum of 8 h) | -Glucose (ND) -Insulin (ND) -Insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR; ND) | -Cholesterol (ND) -LDL (ND) -HDL (ND) -TGs (ND) | -Metabolic rate (ND) -Leptin (ND) -Ghrelin (ND) -BDNF (ND) |

| Trepanowski et al., 2017 [48] | -Adults who were overweight or obese -ADMF; CER | After a 12 h fast, the morning after a “feast” day for the ADMF group | -Glucose (ND) -Insulin (ND) -Insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR; ND) | -Cholesterol (ND) -Greater increase in LDL in ADMF -HDL (ND) -TGs (ND) | -CRP (ND) -Homocysteine (ND) |

| Schübel et al., 2018 [44] | Adults who were overweight or obese -2DW; CER | Metabolic measures sampled day after fed day and an overnight fast | -Fasting glucose decreased more in 2DW than CER -Insulin (ND) -Insulin sensitivity (HOMA-IR; ND) | -Cholesterol (ND) -LDL (ND) -HDL (ND) -TGs (ND) | Not assessed |

| Sundfør et al., 2018 [46] | -Adults who were overweight or obese -2DW; CER | Blood samples were obtained following a minimum of a 10 h fast | Glucose (ND) HbA1c (ND) | -Cholesterol (ND) -LDL (ND) -HDL (ND) -TGs (ND) -Apo B (ND) | -CRP (ND) -Metabolic rate (ND) |

| Hutchison et al., 2019 [49] | -Female adults who were overweight or obese -ADMF 70; ADMF 100; CER | Metabolic measures performed after a fed and fasted day | -Greater decreases in glucose and insulin in ADMF 70 when measured after a fast day -Insulin sensitivity (euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp) increased in ADMF 70 when measured after a fed day, but changes not different than CER -Insulin sensitivity (clamp) decreased in ADMF 70 when measured after a fasted day | -Greater decreases in fasting FFA, TC, LDL, and Tgs in ADMF 70 compared to CER, but ADMF 70 lost more weight -Differences in changes in cholesterol and LDL remained after adjusting for weight loss | Not assessed |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rynders, C.A.; Thomas, E.A.; Zaman, A.; Pan, Z.; Catenacci, V.A.; Melanson, E.L. Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102442

Rynders CA, Thomas EA, Zaman A, Pan Z, Catenacci VA, Melanson EL. Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss. Nutrients. 2019; 11(10):2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102442

Chicago/Turabian StyleRynders, Corey A., Elizabeth A. Thomas, Adnin Zaman, Zhaoxing Pan, Victoria A. Catenacci, and Edward L. Melanson. 2019. "Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss" Nutrients 11, no. 10: 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102442

APA StyleRynders, C. A., Thomas, E. A., Zaman, A., Pan, Z., Catenacci, V. A., & Melanson, E. L. (2019). Effectiveness of Intermittent Fasting and Time-Restricted Feeding Compared to Continuous Energy Restriction for Weight Loss. Nutrients, 11(10), 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102442