Prospective Associations between Single Foods, Alzheimer’s Dementia and Memory Decline in the Elderly

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

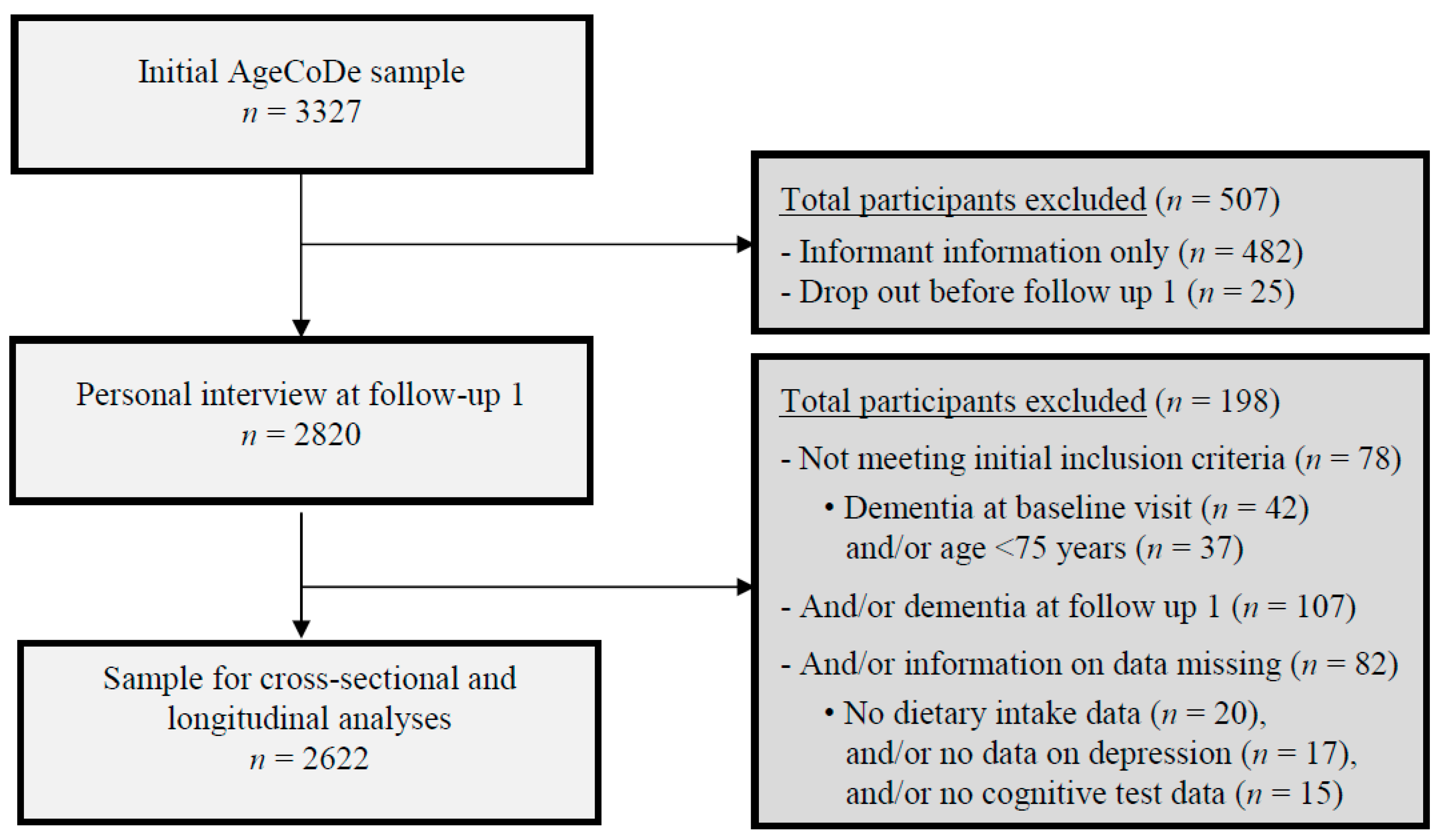

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Analytical Samples

2.3. Dietary Assessment

2.4. Assessment and Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Dementia

2.5. Neuropsychological Assessment

2.6. Assessment of Covariates

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Longitudinal Associations Between Food Intake and Incident AD or Memory Decline in JM

4. Discussion

4.1. Red Wine and White Wine

4.2. Coffee

4.3. Olive Oil

4.4. Fruits and Vegetables

4.5. Meat and Sausages

4.6. Fresh Fish

4.7. Green Tea

4.8. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blennow, K.; de Leon, M.J.; Zetterberg, H. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2006, 368, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jicha, G.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Omega-3 fatty acids: Potential role in the management of early Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Interv. Aging 2010, 5, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brookmeyer, R.; Johnson, E.; Ziegler-Graham, K.; Michael Arrighiet, H. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2007, 3, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.W.; Plassman, B.L.; Burke, J.; Holsinger, T.; Benjamin, S. Preventing Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess. 2010, 193, 1–727. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, I.R. Diet and nutrition in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias of late life. Explore 2005, 1, 299–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Yu, J.T.; Tan, L.; Wang, Y.L.; Sun, L.; Tan, L. Nutrition and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 524820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solfrizzi, V.; Panza, F.; Frisardi, V.; Seripa, D.; Logroscino, G.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Pilotto, A. Diet and Alzheimer’s disease risk factors or prevention: The current evidence. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 677–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parletta, N.; Milte, C.M.; Meyer, B.J. Nutritional modulation of cognitive function and mental health. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 725–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, W.; van Wijk, N.; Cansev, M.; Sijben, J.W.; Kamphuis, P.J. Nutritional approaches in the risk reduction and management of Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrition 2013, 29, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swaminathan, A.; Jicha, G.A. Nutrition and prevention of Alzheimer’s dementia. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otaegui-Arrazola, A.; Amiano, P.; Elbusto, A.; Urdaneta, E.; Martínez-Lage, P. Diet, cognition, and Alzheimer’s disease: Food for thought. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Steffen, L.M. Nutrients, foods, and dietary patterns as exposures in research: A framework for food synergy. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78 (Suppl. 3), 508S–513S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Tapsell, L.C. Food, not nutrients, is the fundamental unit in nutrition. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederholm, T. Fish consumption and omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for prevention or treatment of cognitive decline, dementia or Alzheimer’s disease in older adults—Any news? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2017, 20, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arntzen, K.A.; Schirmer, H.; Wilsgaard, T.; Mathiesen, E.B. Moderate wine consumption is associated with better cognitive test results: A 7 year follow up of 5033 subjects in the Tromso Study. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2010, 122, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berr, C.; Portet, F.; Carriere, I.; Akbaraly, T.N.; Feart, C.; Gourlet, V.; Combe, N.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Ritchie, K. Olive oil and cognition: Results from the three-city study. Dement Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2009, 28, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. Fruit, vegetables and prevention of cognitive decline or dementia: A systematic review of cohort studies. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.P.; Wu, Y.F.; Cheng, H.Y.; Xia, T.; Ding, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.M.; Xu, Y. Habitual coffee consumption and risk of cognitive decline/dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutrition 2016, 32, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, S.A.; Youdim, M.B. In the rush for green gold: Can green tea delay age-progressive brain neurodegeneration? Recent Pat. CNS Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, H.J.; Shim, S.B.; Jee, S.W.; Lee, S.H.; Lim, C.J.; Hong, J.T.; Sheen, Y.Y.; Hwang, D.Y. Green tea catechin leads to global improvement among Alzheimer’s disease-related phenotypes in NSE/hAPP-C105 Tg mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013, 24, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi-Shinohara, M.; Yuki, S.; Dohmoto, C.; Ikeda, Y.; Samuraki, M.; Iwasa, K.; Yokogawa, M.; Asai, K.; Komai, K.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Consumption of green tea, but not black tea or coffee, is associated with reduced risk of cognitive decline. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albanese, E.; Dangour, A.D.; Uauy, R.; Acosta, D.; Guerra, M.; Guerra, S.S.G.; Huang, Y.Q.; Jacob, K.S.; Rodriguez, J.L.d.; Noriega, L.H. Dietary fish and meat intake and dementia in Latin America, China, and India: A 10/66 Dementia Research Group population-based study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giem, P.; Beeson, W.L.; Fraser, G.E. The incidence of dementia and intake of animal products: Preliminary findings from the Adventist Health Study. Neuroepidemiology 1993, 12, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberger-Gateau, P.; Letenneur, L.; Deschamps, V.; Pérès, K.; Dartigues, J.F.; Renaud, S. Fish, meat, and risk of dementia: Cohort study. BMJ 2002, 325, 932–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.C.; Evans, D.A.; Hebert, L.E.; Bienias, J.L. Methodological issues in the study of cognitive decline. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1999, 149, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, T.G.; Chouinard-Watkins, R.; Plourde, M. Carriers of an apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 allele are more vulnerable to a dietary deficiency in omega-3 fatty acids and cognitive decline. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1862, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberger-Gateau, P.; Samieri, C.; Féart, C.; Plourdeet, M. Dietary omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and Alzheimer’s disease: Interaction with apolipoprotein E genotype. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2011, 8, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.J.; Blumenthal, J.A. Dietary Factors and Cognitive Decline. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.C. Nutrition and risk of dementia: Overview and methodological issues. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2016, 1367, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunce, D.; Kivipelto, M.; Wahlin, A. Utilization of cognitive support in episodic free recall as a function of apolipoprotein E and vitamin B12 or folate among adults aged 75 years and older. Neuropsychology 2004, 18, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.L.; Zandi, P.P.; Tucker, K.L.; Fitzpatrick, A.L.; Kuller, L.H.; Fried, L.P.; Burke, G.L.; Carlson, M.C. Benefits of fatty fish on dementia risk are stronger for those without APOE epsilon4. Neurology 2005, 65, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Galbete, C.; Corella, D.; Toledo, E.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Martínez-González, M.Á. Genotype patterns at CLU, CR1, PICALM and APOE, cognition and Mediterranean diet: The PREDIMED-NAVARRA trial. Genes Nutr. 2014, 9, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Rest, O.; Wang, Y.; Barnes, L.L.; Tangney, C.; Bennett, D.A.; Morriset, M.C. APOE epsilon4 and the associations of seafood and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids with cognitive decline. Neurology 2016, 86, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudorache, I.F.; Trusca, V.G.; Gafencu, A.V. Apolipoprotein E—A Multifunctional Protein with Implications in Various Pathologies as a Result of Its Structural Features. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, C.C.; Qiao, W.; Bu, G. Apolipoprotein E, Receptors, and Modulation of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 83, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniewski, T.; Frangione, B. Apolipoprotein E: A pathological chaperone protein in patients with cerebral and systemic amyloid. Neurosci. Lett. 1992, 135, 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, L.; Biggs, M.L.; O’Meara, E.S.; Longstreth, W.T.; Crane, P.K.; Fitzpatrick, A.L. Gender differences in tea, coffee, and cognitive decline in the elderly: The Cardiovascular Health Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2011, 27, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassek, W.D.; Gaulin, S.J. Sex differences in the relationship of dietary Fatty acids to cognitive measures in american children. Front. Evol. Neurosci. 2011, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, L.F.; Mirza, S.S.; Bos, D.; Niessen, W.J.; Barreto, S.M.; van der Lugt, A.; Vernooij, M.W.; Hofman, A.; Tiemeier, H.; Ikram, M.A. Association of Coffee Consumption with MRI Markers and Cognitive Function: A Population-Based Study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016, 53, 451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiatis, A.A.; Davidian, M. Joint Modeling of longitudinal and time-to-event data: An overview. Stat. Sin. 2004, 14, 809–834. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, J.G.; Chu, H.; Chen, L.M. Basic concepts and methods for joint models of longitudinal and survival data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2796–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudell, M.; Kolamunnage-Dona, R.; Tudur-Smith, C. Joint models for longitudinal and time-to-event data: A review of reporting quality with a view to meta-analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asar, O.; Ritchie, J.; Kalra, P.A.; Diggle, P.J. Joint modelling of repeated measurement and time-to-event data: An introductory tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luck, T.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Bickel, H.; Jessen, F.; Pentzek, M.; Wiese, B.; Koelsch, H.; van den Bussche, H.; Abholz, H.H.; et al. Mild cognitive impairment in general practice: Age-specific prevalence and correlate results from the German study on ageing, cognition and dementia in primary care patients (AgeCoDe). Dement Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007, 24, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jessen, F.; Wiese, B.; Bickel, H.; Eiffländer-Gorfer, S.; Fuchs, A.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Köhler, M.; Luck, T.; Mösch, E.; Pentzek, M.; et al. Prediction of dementia in primary care patients. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, B.; Bickel, H.; Schaufele, M. The ability of general-practitioners to detect dementia and cognitive impairment in their elderly patients—A study in Mannheim. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1992, 7, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaudig, M.; Hiller, W. SIDAM-Handbuch Strukturiertes Interview für die Diagnose einer Demenz vom Alzheimer Typ, der Multiinfarkt- (Oder Vaskulären) Demenz und Demenzen Anderer Ätiologie nach DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, ICD-10; Hans Huber: Bern, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zaudig, M.; Mittelhammer, J.; Hiller, W.; Pauls, A.; Thora, C.; Morinigo, A.; Mombour, W. SIDAM—A structured interview for the diagnosis of dementia of the Alzheimer type, multi-infarct dementia and dementias of other aetiology according to ICD-10 and DSM-III-R. Psychol. Med. 1991, 21, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKhann, G.; Drachman, D.; Folstein, M.; Katzman, R.; Price, D.; Stadlanet, E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984, 34, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Román, G.C.; Tatemichi, T.K.; Erkinjuntti, T.; Cummings, J.L.; Masdeu, J.C.; Garcia, J.H.; Amaducci, L.; Orgogozo, J.M.; Brun, A.; Hofman, A. Vascular dementia: Diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN International Workshop. Neurology 1993, 43, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisberg, B.; Ferris, S.H.; de Leon, M.J.; Crook, T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry 1982, 139, 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blessed, G. The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in the cerebral grey matter of elderly subjects—Retrospective. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1996, 11, 1036–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Moms, J.C.; Heyman, A.; Mohs, R.C.; Hughes, J.P.; Belle, G.v.; Fillenbaum, G.; Mellits, E.D.; Clarket, C. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1989, 39, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauns, H.; Steinmann, S. Educational reform in France, West-Germany and the United Kingdom: Updating the CASMIN educational classification. ZUMA Nachr. 1999, 23, 7–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hixson, J.E.; Vernier, D.T. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J. Lipid Res. 1990, 31, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Verghese, J.; Lipton, R.B.; Katz, M.J.; Hall, C.B.; Derby, C.A.; Kuslansky, G.; Ambrose, A.F.; Sliwinski, M.; Buschke, H. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 2508–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, J.I.; Yesavage, J.A.; Brooks, J.O.; Friedman, L.; Gratzinger, P.; Hill, R.D.; Zadeik, A.; Crook, T. Proposed factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int. Psychogeriatr. 1991, 3, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauggel, S.; Birkner, B. Birkner, Validity and reliability of a German version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Z. Fur Klin. Psychol.-Forsch. Praxis 1999, 28, 373–383. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, M.; Cauchi, R.; Vassallo, N. Putative Role of Red Wine Polyphenols against Brain Pathology in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasanthi, H.R.; Parameswari, R.P.; DeLeiris, J.; Das, D.K. Health benefits of wine and alcohol from neuroprotection to heart health. Front. Biosci. 2012, 4, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basli, A.; Soulet, S.; Chaher, N.; Mérillon, J.M.; Chibane, M.; Monti, J.P.; Richard, T. Wine polyphenols: Potential agents in neuroprotection. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 805762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granzotto, A.; Zatta, P. Resveratrol and Alzheimer’s disease: Message in a bottle on red wine and cognition. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyerer, S.; Schäufele, M.; Wiese, B.; Maier, W.; Tebarth, F.; van den Bussche, H.; Pentzek, M.; Bickel, H.; Luppa, M.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; et al. Current alcohol consumption and its relationship to incident dementia: Results from a 3-year follow-up study among primary care attenders aged 75 years and older. Age Ageing 2011, 40, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, R.; Peters, J.; Warner, J.; Beckett, N.; Bulpitt, C. Alcohol, dementia and cognitive decline in the elderly: A systematic review. Age Ageing 2008, 37, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuccalà, G.; Onder, G.; Pedone, C.; Cesari, M.; Landi, F.; Bernabei, R.; Cocchi, A.; Gruppo Italiano di Farmacoepidemiologia nell’Anziano Investigatorset. Dose-related impact of alcohol consumption on cognitive function in advanced age: Results of a multicenter survey. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2001, 25, 1743–1748. [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun, M.A.; Beydoun, H.A.; Gamaldo, A.A.; Teel, A.; Zonderman, A.B.; Wang, F. Epidemiologic studies of modifiable factors associated with cognition and dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, F.; Frisardi, V.; Seripa, D.; Logroscino, G.; Santamato, A.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Scafato, E.; Pilotto, A.; Solfrizzi, V. Alcohol consumption in mild cognitive impairment and dementia: harmful or neuroprotective? Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2012, 27, 1218–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukitt-Hale, B.; Miller, M.G.; Chu, Y.F.; Lyle, B.J.; Joseph, J.A. Coffee, but not caffeine, has positive effects on cognition and psychomotor behavior in aging. Age 2013, 35, 2183–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higdon, J.V.; Frei, B. Coffee and health: A review of recent human research. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2006, 46, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, F.; Solfrizzi, V.; Barulli, M.R.; Bonfiglio, C.; Guerra, V.; Osella, A.; Seripa, D.; Sabbà, C.; Pilotto, A.; Logroscino, G.; et al. Coffee, tea, and caffeine consumption and prevention of late-life cognitive decline and dementia: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Igna, O.P.; Fett, P.; Gomes, M.W.; Souza, D.O.; Cunha, R.A.; Lara, D.R. Caffeine and adenosine A(2a) receptor antagonists prevent beta-amyloid (25-35)-induced cognitive deficits in mice. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 203, 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen, M.H.; Ngandu, T.; Tuomilehto, J.; Soininen, H.; Kivipelto, M. Midlife coffee and tea drinking and the risk of late-life dementia: A population-based CAIDE study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009, 16, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, J.; Laurin, D.; Verreault, R.; Hébert, R.; Helliwell, B.; Hill, G.B.; McDowell, I. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: A prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 156, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Lapiscina, E.H.; Clavero, P.; Toledo, E.; San Julián, B.; Sanchez-Tainta, A.; Corella, D.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Martínez, J.A.; Martínez-Gonzalez, M.Á. Virgin olive oil supplementation and long-term cognition: The PREDIMED-NAVARRA randomized, trial. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiao, J. Intakes of fish and polyunsaturated fatty acids and mild-to-severe cognitive impairment risks: A dose-response meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.G.; Thangthaeng, N.; Poulose, S.M.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Role of fruits, nuts, and vegetables in maintaining cognitive health. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 94, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusufov, M.; Weyandt, L.L.; Piryatinsky, I. Alzheimer’s disease and diet: A systematic review. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granic, A.; Davies, K.; Adamson, A.; Kirkwood, T.; Hill, T.R.; Siervo, M.; Mathers, J.C.; Jagger, C. Dietary Patterns High in Red Meat, Potato, Gravy, and Butter Are Associated with Poor Cognitive Functioning but Not with Rate of Cognitive Decline in Very Old Adults. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; An, P.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Shen, X.; Li, X.; Min, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, F. Dietary intake of heme iron and risk of cardiovascular disease: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, L.H.; Kondrup, J.; Zellner, M.; Tetens, I.; Roth, E. Effect of a high protein meat diet on muscle and cognitive functions: A randomised controlled dietary intervention trial in healthy men. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 30, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhar, Z.M.; Zubaidah, J.O.; Norjan, K.O.N.; Zhuang, C.Y.J.; Fai, T. A pilot placebo-controlled, double-blind, and randomized study on the cognition-enhancing benefits of a proprietary chicken meat ingredient in healthy subjects. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotuhi, M.; Mohassel, P.; Yaffe, K. Fish consumption, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cognitive decline or Alzheimer disease: A complex association. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2009, 5, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daiello, L.A.; Gongvatana, A.; Dunsiger, S.; Cohen, R.A.; Ottet, B.R. Association of fish oil supplement use with preservation of brain volume and cognitive function. Alzheimers Dement 2015, 11, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, N., Jr.; Vandal, M.; Calon, F. The benefit of docosahexaenoic acid for the adult brain in aging and dementia. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat. Acids 2015, 92, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, T.P.; Feng, L.; Niti, M.; Kua, E.H.; Yap, K.B. Tea consumption and cognitive impairment and decline in older Chinese adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesan, R.; Ji, E.; Kim, S.Y. Phytochemicals that regulate neurodegenerative disease by targeting neurotrophins: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 814068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandel, S.A.; Weinreb, O.; Amit, T.; Youdim, M.B. Molecular mechanisms of the neuroprotective/neurorescue action of multi-target green tea polyphenols. Front. Biosci. 2012, 4, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, C.; Dekker, M. Effect of Green Tea Phytochemicals on Mood and Cognition. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 2876–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rains, T.M.; Agarwal, S.; Maki, K.C. Antiobesity effects of green tea catechins: A mechanistic review. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, K.J. Epidemiology—An Introduction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martinez-González, M.Z.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Volkert, D.; Schrader, E. Dietary assessment methods for older persons: What is the best approach? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, G.; Gillespie, C.; Rosenbaum, E.H.; Jenson, C. A rapid food screener to assess fat and fruit and vegetable intake. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 18, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topiwala, A.; Allan, C.L.; Valkanova, V.; Zsoldos, E.; Filippini, N.; Sexton, C.; Mahmood, A.; Fooks, P.; Singh-Manoux, A.; Mackay, C.E.; et al. Moderate alcohol consumption as risk factor for adverse brain outcomes and cognitive decline: Longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2017, 357, j2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.C.; Evans, D.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Bienias, J.L.; Wilson, R.S. Associations of vegetable and fruit consumption with age-related cognitive change. Neurology 2006, 67, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant Characteristics | Total Population (n = 2622) | Men (n = 910) | Women (n = 1712) | P | APOE ε4 Carriers (n = 551) | APOE ε4 Non-Carriers (n = 2071) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 81.2 ± 3.4 | 80.9 ± 3.4 | 81.3 ± 3.4 | 0.001 | 80.9 ± 3.3 | 81.2 ± 3.5 | 0.035 |

| Female (n (%)) | 1712 (65.3) | - | - | - | 358 (65.1) | 1354 (65.3) | 0.886 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 ± 3.3 | 26.1 ± 2.8 | 25.7 ± 3.5 | 0.003 | 25.6 ± 3.1 | 25.9 ± 3.4. | 0.048 |

| APOE ε4 status (n (%)) | 551 (21.0) | 193 (21.2) | 358 (20.9) | 0.886 | - | - | - |

| Education (n (%)) | <0.001 | 0.164 | |||||

| Low | 1594 (60.8) | 483 (53.1) | 1111 (64.9) | 327 (59.3) | 1267(61.2) | ||

| Middle | 723 (27.6) | 220 (24.2) | 503 (29.4) | 168 (30.5) | 555 (26.8) | ||

| High | 305 (11.6) | 207 (22.7) | 98 (5.7) | 56 (10.2) | 249 (12.0) | ||

| Physical activity (n (%)) | 0.048 | 0.252 | |||||

| Low (0 ≥ 3) | 833 (31.8) | 277 (30.4) | 556 (32.5) | 161 (29.2) | 672 (32.5) | ||

| Middle (3 ≤ 5) | 897 (34.2) | 296 (32.5) | 601 (35.1) | 204 (37.0) | 693 (33.5) | ||

| High (5–11) | 892 (34.0) | 337 (37.0) | 555 (32.4) | 186 (33.8) | 706 (34.0) | ||

| Smoking (n (%)) | <0.001 | 0.561 | |||||

| Never | 1307 (49.8) | 178 (19.6) | 1129 (66.0) | 277 (50.3) | 1030 (49.7) | ||

| Past | 1125 (42.9) | 662 (72.7) | 463 (27.0) | 229 (41.5) | 896 (43.3) | ||

| Current | 190 (7.3) | 70 (7.7) | 120 (7.0) | 45 (8.2) | 145 (7.0) | ||

| MCI (n (%)) | 436 (16.6) | 121 (13.3) | 315 (18.4) | 0.001 | 119 (21.7) | 318 (15.4) | 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia (n (%)) | 1408 (53.7) | 446 (49.0) | 962 (56.2) | 0.094 | 317 (57.5) | 1091 (52.7) | 0.014 |

| Depression (n (%)) | 298 (11.4) | 80 (8.8) | 218 (12.7) | 0.002 | 67 (12.1) | 231 (11.2) | 0.345 |

| Modified CCI score (0–6) (n (%)) | <0.001 | 0.215 | |||||

| Score 0–2 | 1866 (71.2) | 585 (64.3) | 1281 (74.8) | 408 (74.1) | 1458 (70.4) | ||

| Score 3–4 | 666 (25.4) | 284 (31.2) | 382 (22.3) | 124 (22.5) | 542 (26.2) | ||

| Score 5–6 | 90 (3.4) | 41 (4.5) | 49 (2.9) | 19 (3.4) | 71 (3.4) | ||

| CERAD memory (score 0–100) | 71.7 ± 13.0 | 69.3 ± 12.8 | 73.0 ± 13.0 | <0.001 | 69.4 ± 13.6 | 72.3 ± 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Time to develop AD (years) | 4.5 ± 2.8 | 4.2 ± 2.7 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 0.133 | 4.2 ± 2.7 | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 0.183 |

| Time to censoring (years) | 5.9 ± 3.3 | 5.7 ± 3.3 | 6.0 ± 3.3 | 0.047 | 5.6 ± 3.3 | 6.0 ± 3.3 | 0.021 |

| Food Intake Frequencies (%) | Total Population | Men | Women | APOE ε4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers | Non-Carriers | ||||

| (n = 2622) | (n = 910) | (n = 1712) | (n = 551) | (n = 2071) | |

| Fruits and vegetables a | |||||

| Never | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| <1 time/week | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | - | 0.2 |

| 1 time/week | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Several times/week | 14.8 | 18.5 | 12.9 | 17.1 | 14.2 |

| Every day | 84.2 | 79.8 | 86.6 | 82.4 | 84.7 |

| Fresh fish | |||||

| Never | 7.2 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 6.7 | 7.3 |

| <1 time/week | 30.0 | 26.6 | 31.8 | 31.2 | 29.6 |

| 1 time/week | 44.9 | 49.0 | 42.7 | 42.3 | 45.6 |

| Several times/week | 17.8 | 17.4 | 18.0 | 19.6 | 17.3 |

| Every day | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Olive oil | |||||

| Never | 36.3 | 32.1 | 38.6 | 38.3 | 35.2 |

| <1 time/week | 12.2 | 13.0 | 11.9 | 10.3 | 12.5 |

| 1 time/week | 8.2 | 7.7 | 8.5 | 9.1 | 7.8 |

| Several times/week | 32.2 | 35.8 | 30.2 | 32.7 | 31.5 |

| Every day | 11.1 | 11.4 | 10.9 | 9.6 | 13.0 |

| Meat and sausages a | |||||

| Never | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| <1 time/week | 2.6 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.5 |

| 1 time/week | 8.5 | 3.5 | 11.2 | 9.6 | 8.2 |

| Several times/week | 51.3 | 45.9 | 54.1 | 49.9 | 51.6 |

| Every day | 36.6 | 48.9 | 30.1 | 36.3 | 36.7 |

| Red wine | |||||

| Never | 52.2 | 38.6 | 59.4 | 52.3 | 52.1 |

| <1 time/week | 20.4 | 22.0 | 19.6 | 21.4 | 20.2 |

| 1 time/week | 9.2 | 11.3 | 8.1 | 9.1 | 9.3 |

| Several times/week | 10.7 | 16.7 | 7.5 | 9.8 | 10.9 |

| Every day | 7.5 | 11.4 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 7.5 |

| White wine | |||||

| Not at all | 64.4 | 51.4 | 71.3 | 61.9 | 65.1 |

| <1 time/week | 20.6 | 25.3 | 18.2 | 22.0 | 20.3 |

| 1 time/week | 6.1 | 9.6 | 4.3 | 7.3 | 5.8 |

| Several times/week | 7.0 | 11.1 | 4.8 | 6.9 | 7.0 |

| Every day | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Coffee | |||||

| Never | 13.2 | 13.0 | 13.3 | 13.1 | 13.2 |

| <1 time/week | 5.2 | 5.9 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 5.5 |

| 1 time/week | 3.4 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.5 |

| Several times/week | 6.6 | 7.3 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 6.7 |

| Every day | 71.6 | 70.0 | 72.5 | 73.5 | 71.1 |

| Green tea | |||||

| Never | 67.7 | 71.1 | 65.9 | 69.3 | 67.3 |

| <1 time/week | 12.6 | 12.0 | 12.9 | 11.1 | 12.9 |

| 1 time/week | 5.0 | 3.2 | 6.0 | 4.4 | 5.2 |

| Several times/week | 8.2 | 5.8 | 9.5 | 7.8 | 8.4 |

| Every day | 6.4 | 7.9 | 5.6 | 7.4 | 6.2 |

| Associations between Food Intake and Incident AD or Memory Decline | HR (95% CI) for Incident AD and UnstandardizedRegression Coefficients (95% CI) for Memory Decline | Significant P-Values for Interaction (P < 0.10) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | Gender | APOE ε4 status | ||

| Incident AD | ||||

| (survival sub-model) | HR (95%CI) | P | ||

| Fruits and vegetables | 1.08 (0.80; 1.46) | 0.609 | - | 0.085 |

| Fresh fish | 0.98 (0.87; 1.11) | 0.754 | - | - |

| Olive oil | 1.00 (0.93; 1.07) | 0.969 | - | - |

| Meat and sausages | 1.09 (0.94; 1.26) | 0.236 | - | 0.083 |

| Red wine | 0.92 (0.85; 0.99) | 0.045 | 0.001 | - |

| White wine | 1.00 (0.91; 1.12) | 0.875 | - | 0.074 |

| Coffee | 0.97 (0.90; 1.04) | 0.338 | - | - |

| Green tea | 0.94 (0.86; 1.02) | 0.129 | - | - |

| Memory decline | ||||

| (repeated-measures sub-model) | B (95%CI) | P | ||

| Fruits and vegetables | 0.10 (−0.14; 0.33) | 0.408 | - | - |

| Fresh fish | −0.03 (−0.14; 0.08) | 0.610 | - | - |

| Olive oil | −0.03 (−0.09; 0.04) | 0.388 | 0.064 | - |

| Meat and sausages | 0.01 (−0.11; 0.14) | 0.845 | - | - |

| Red wine | −0.04 (−0.11; 0.03) | 0.302 | - | - |

| White wine | −0.03 (−0.12; 0.06) | 0.494 | 0.085 | - |

| Coffee | −0.02 (−0.08; 0.05) | 0.241 | - | 0.056 |

| Green tea | 0.02 (−0.06; 0.09) | 0.681 | - | - |

| Food Intake (Score 0–4) | Incidence of AD (Model 2) | Memory Decline (Model 2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | B (95% CI) | P | |

| By gender | ||||

| Olive oil | ||||

| Men (n = 910) | 0.06 (−0.05; 0.16) | 0.285 | ||

| Women (n = 1712) | −0.08 (−0.16; 0.01) | 0.065 | ||

| Red wine | ||||

| Men (n = 910) | 0.82 (0.74; 0.92) | <0.001 | ||

| Women (n = 1712) | 1.15 (1.00; 1.32) | 0.044 | ||

| White wine | ||||

| Men (n = 910) | 0.04 (−0.09; 0.17) | 0.562 | ||

| Women (n = 1712) | −0.13 (−0.26; 0.001) | 0.052 | ||

| By APOE ε4 status | ||||

| Fruits and vegetables | ||||

| APOE ε4 carrier (n = 552) | 1.29 (0.73; 2.27) | 0.388 | ||

| APOE ε4 non-carrier (n = 2070) | 1.17 (0.88; 1.55) | 0.287 | ||

| Meat and sausages | ||||

| APOE ε4 carrier (n = 552) | 1.13 (0.90; 1.42) | 0.293 | ||

| APOE ε4 non-carrier (n = 2070) | 1.04 (0.87; 1.22) | 0.615 | ||

| White wine | ||||

| APOE ε4 carrier (n = 552) | 1.21 (1.01; 1.46) | 0.044 | ||

| APOE ε4 non-carrier (n = 2070) | 0.93 (0.82; 1.06) | 0.245 | ||

| Coffee | ||||

| APOE ε4 carrier (n = 552) | 0.11 (−0.06; 0.29) | 0.202 | ||

| APOE ε4 non-carrier (n = 2070) | −0.04 (−0.11; 0.02) | 0.211 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fischer, K.; Melo van Lent, D.; Wolfsgruber, S.; Weinhold, L.; Kleineidam, L.; Bickel, H.; Scherer, M.; Eisele, M.; Van den Bussche, H.; Wiese, B.; et al. Prospective Associations between Single Foods, Alzheimer’s Dementia and Memory Decline in the Elderly. Nutrients 2018, 10, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10070852

Fischer K, Melo van Lent D, Wolfsgruber S, Weinhold L, Kleineidam L, Bickel H, Scherer M, Eisele M, Van den Bussche H, Wiese B, et al. Prospective Associations between Single Foods, Alzheimer’s Dementia and Memory Decline in the Elderly. Nutrients. 2018; 10(7):852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10070852

Chicago/Turabian StyleFischer, Karina, Debora Melo van Lent, Steffen Wolfsgruber, Leonie Weinhold, Luca Kleineidam, Horst Bickel, Martin Scherer, Marion Eisele, Hendrik Van den Bussche, Birgitt Wiese, and et al. 2018. "Prospective Associations between Single Foods, Alzheimer’s Dementia and Memory Decline in the Elderly" Nutrients 10, no. 7: 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10070852

APA StyleFischer, K., Melo van Lent, D., Wolfsgruber, S., Weinhold, L., Kleineidam, L., Bickel, H., Scherer, M., Eisele, M., Van den Bussche, H., Wiese, B., König, H.-H., Weyerer, S., Pentzek, M., Röhr, S., Maier, W., Jessen, F., Schmid, M., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & Wagner, M. (2018). Prospective Associations between Single Foods, Alzheimer’s Dementia and Memory Decline in the Elderly. Nutrients, 10(7), 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10070852