Starchy Carbohydrates in a Healthy Diet: The Role of the Humble Potato

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Nutrient Composition

2.1. Macronutrients

2.1.1. Carbohydrate

2.1.2. Fibre

2.1.2.1. Resistant Starch

2.1.3. Protein and Fat

2.2. Micronutrients

2.3. Phytonutrients

2.4. Effects of Potato Variety on Nutrient Composition

2.5. Effects of Storage on Nutrient Composition

3. Relationship between Potato Consumption and Non-Communicable Diseases

3.1. Obesity

3.2. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

3.3 Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) and CVD Risk Factors

4. Conclusions

- The nutritional content of a medium-sized baked potato weighing 200 g can provide a significant contribution to vitamin and micronutrient needs, containing almost half of the UK daily RNI for a man for vitamin C and vitamin B6, 30% for potassium, 28% for folate, 24% for iron, and 18% for magnesium.

- The total fibre content of 4.4 g is 15% of the 30 g per day recommended for an adult. However, these figures are markedly altered by the cooking method, for example, the vitamin C content would be 50% higher in a microwaved potato, and the iron content would be reduced by over 70%.

- A major limitation when assessing the nutrient quality of the potato is that the RS content of potatoes is not included in the gold standard AOAC method for total fibre. Therefore, the total fibre content of potatoes listed in food databases underestimates actual total fibre content, and consequently the nutritional value.

- The interaction between meal components, such as starch and lipid, is a somewhat under-explored but particularly exciting and important area, as there is the potential to change the RS starch content of a meal by making simple changes to cooking methods. Considering other meal components and portion size is also important with respect to the overall GL of a meal.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. SACN Carbohydrates and Health Report; Public Health England: London, UK, 2015.

- Seidelmann, S.B.; Claggett, B.; Cheng, S.; Henglin, M.; Shah, A.; Steffen, L.M.; Folsom, A.R.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Solomon, S.D. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: A prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Cummings, J.H.; Englyst, H.N.; Key, T.; Liu, S.; Riccardi, G.; Summerbell, C.; Uauy, R.; van Dam, R.M.; Venn, B.; et al. FAO/WHO Scientific Update on carbohydrates in human nutrition: Conclusions. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, S132–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eat Well—NHS.UK. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/ (accessed on 6 August 2018).

- Haverkort, A.J.; de Ruijter, F.J.; van Evert, F.K.; Conijn, J.G.; Rutgers, B. Worldwide Sustainability Hotspots in Potato Cultivation. 1. Identification and Mapping. Potato Res. 2013, 56, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Sansonetti, G. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. New Light on a Hidden Treasure: International Year of the Potato 2008, an End-of-Year Review; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, H. Potato consumption in the UK—Why is “meat and two veg” no longer the traditional British meal? Nutr. Bull. 2010, 35, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlingame, B.; Mouillé, B.; Charrondière, R. Nutrients, bioactive non-nutrients and anti-nutrients in potatoes. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrell, P.J.; Meiyalaghan, S.; Jacobs, J.M.E.; Conner, A.J. Applications of biotechnology and genomics in potato improvement. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013, 11, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

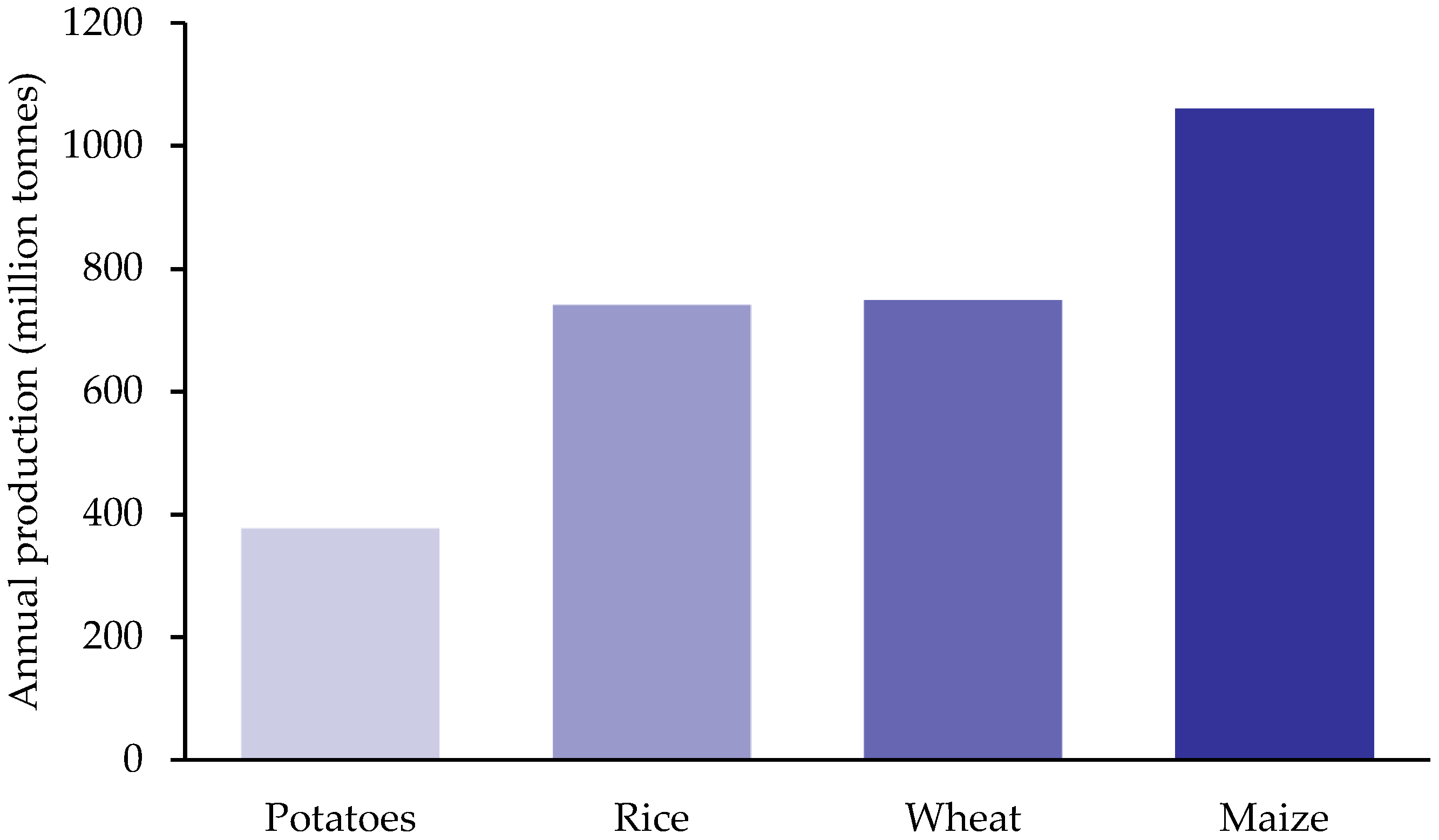

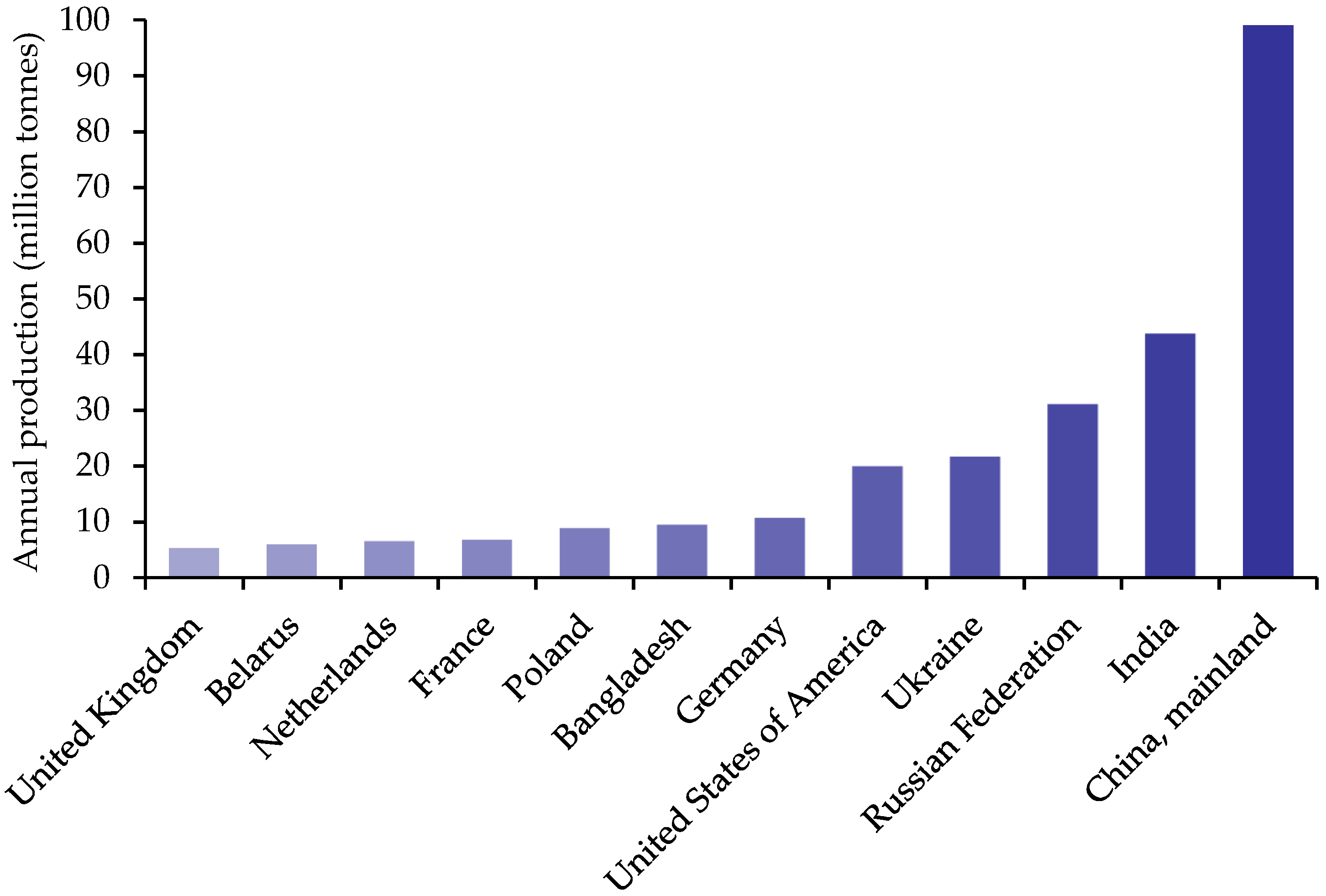

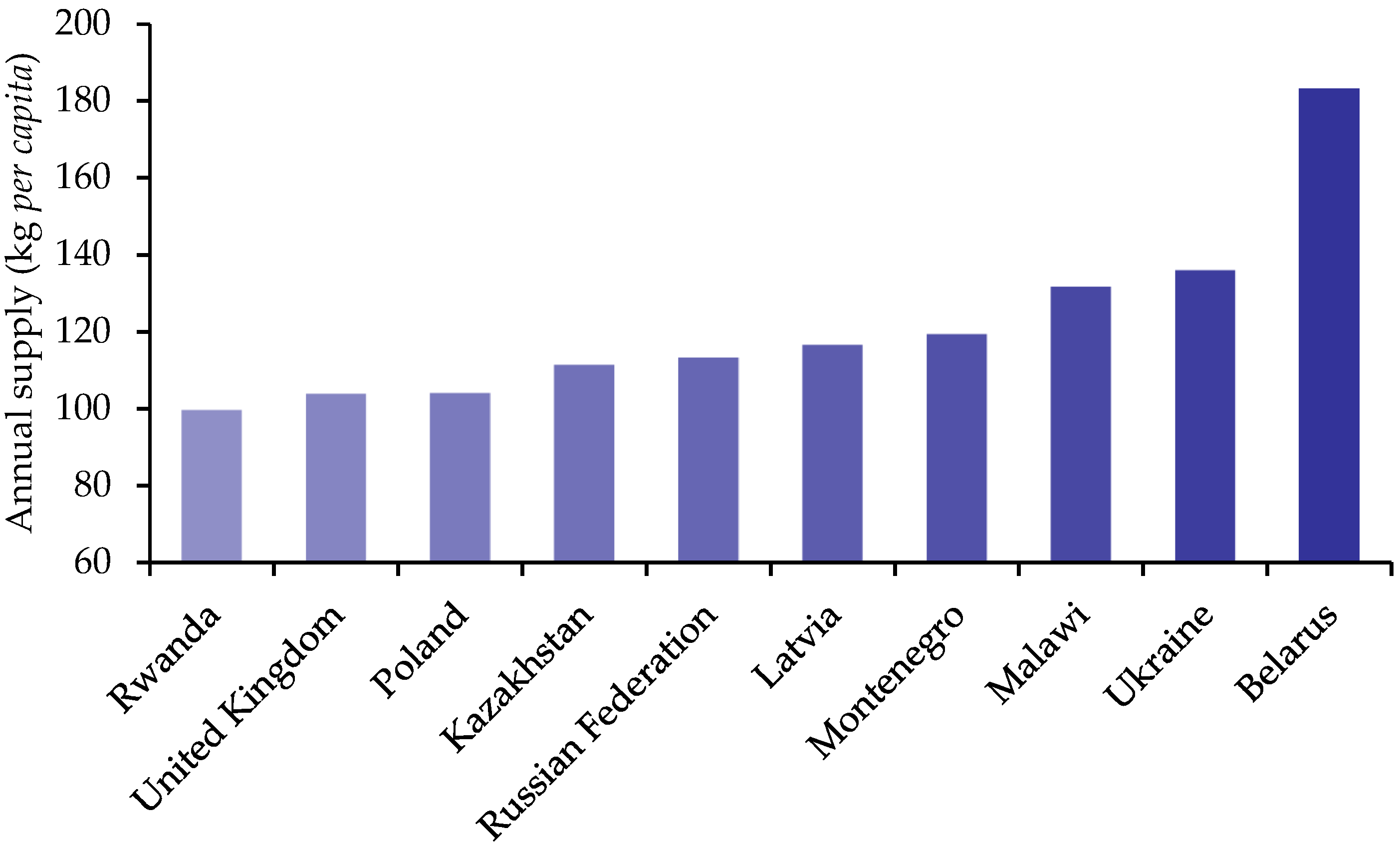

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 23 August 2018).

- Ranum, P.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Garcia-Casal, M.N. Global maize production, utilization, and consumption. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1312, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCollum, E.V.; Simmonds, N.; Parsons, H.T. The dietary properties of the potato. J. Biol. Chem. 1918, 36, 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, S.; Kurilich, A.C. The nutritional value of potatoes and potato products in the UK diet. Nutr. Bull. 2013, 38, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Family Food 2016/17: Purchases—GOV.UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/family-food-201617/purchases (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Attah, A.O.; Braaten, T.; Skeie, G. Change in potato consumption among Norwegian women 1998–2005-The Norwegian Women and Cancer study (NOWAC). PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churuangsuk, C.; Kherouf, M.; Combet, E.; Lean, M. Low-carbohydrate diets for overweight and obesity: A systematic review of the systematic reviews. Obes. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camire, M.E.; Kubow, S.; Donnelly, D.J. Potatoes and Human Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 823–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borch, D.; Juul-Hindsgaul, N.; Veller, M.; Astrup, A.; Jaskolowski, J.; Raben, A. Potatoes and risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy adults: A systematic review of clinical intervention and observational studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Boeing, H. Potatoes and risk of chronic disease: A systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, C.R.; Kurilich, A.C.; Davignon, J. The role of potatoes and potato components in cardiometabolic health: A review. Ann. Med. 2013, 45, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.C.; Slavin, J.L. White potatoes, human health, and dietary guidance. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 393S–401S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Chen, J.; Ye, X.; Chen, S. Health benefits of the potato affected by domestic cooking: A review. Food Chem. 2016, 202, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeeman, S.C.; Kossmann, J.; Smith, A.M. Starch: Its Metabolism, Evolution, and Biotechnological Modification in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewosz, J.; Reda, S.; Ryś, D.; Jastrzębski, K.; Piątek, I. Chemical composition of potato tubers and their resistance on mechanical damage. Biul. Inst. Ziemn. 1976, 18, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kita, A. The influence of potato chemical composition on crisp texture. Food Chem. 2002, 76, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Results from Years 7 and 8 (Combined) of the Rolling Programme (2014/2015 to 2015/2016); Public Health England: London, UK, 2018.

- Slavin, J.L. Carbohydrates, Dietary Fiber, and Resistant Starch in White Vegetables: Links to Health Outcomes. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 351S–355S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.-D.; Xu, T.-C.; Xiao, J.-X.; Zong, A.-Z.; Qiu, B.; Jia, M.; Liu, L.-N.; Liu, W. Efficacy of potato resistant starch prepared by microwave–toughening treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 192, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Andersson, M.; Andersson, R. Resistant starch and other dietary fiber components in tubers from a high-amylose potato. Food Chem. 2018, 251, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Achaerandio, I.; Pujolà, M. Effect of the intensity of cooking methods on the nutritional and physical properties of potato tubers. Food Chem. 2016, 197, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goñi, I.; Bravo, L.; Larrauri, J.A.; Calixto, F.S. Resistant starch in potatoes deep-fried in olive oil. Food Chem. 1997, 59, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raatz, S.K.; Idso, L.; Johnson, L.K.; Jackson, M.I.; Combs, G.F. Resistant starch analysis of commonly consumed potatoes: Content varies by cooking method and service temperature but not by variety. Food Chem. 2016, 208, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, K.; Takato, S.; Ueda, M.; Ohnishi, N.; Viriyarattanasak, C.; Kajiwara, K. Effects of fatty acid and emulsifier on the complex formation and in vitro digestibility of gelatinized potato starch. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 1500–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Yadav, B. Effect of frying, baking and storage conditions on resistant starch content of foods. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Nutrition Foundation. Protein. Available online: https://www.nutrition.org.uk/nutritionscience/nutrients-food-and-ingredients/protein.html (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Helle, S.; Bray, F.; Verbeke, J.; Devassine, S.; Courseaux, A.; Facon, M.; Tokarski, C.; Rolando, C.; Szydlowski, N. Proteome Analysis of Potato Starch Reveals the Presence of New Starch Metabolic Proteins as Well as Multiple Protease Inhibitors. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USDA Food Composition Databases. Available online: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/ (accessed on 6 August 2018).

- Bethke, P.C.; Jansky, S.H. The Effects of Boiling and Leaching on the Content of Potassium and Other Minerals in Potatoes. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, H80–H85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finglas, P.M.; Faulks, R.M. Nutritional composition of UK retail potatoes, both raw and cooked. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1984, 35, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-S.; Kozukue, N.; Young, K.-S.; Lee, K.-R.; Friedman, M. Distribution of Ascorbic Acid in Potato Tubers and in Home-Processed and Commercial Potato Foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 6516–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachman, J.; Hamouz, K. Red and purple coloured potatoes as a significant antioxidant source in human nutrition—A review. Plant Soil Environ. 2005, 51, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.-F.; Sun, J.; Wu, X.; Liu, R.H. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Common Vegetables. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6910–6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyoung Chun, O.; Kim, D.-O.; Smith, N.; Schroeder, D.; Taek Han, J.; Yong Lee, C. Daily consumption of phenolics and total antioxidant capacity from fruit and vegetables in the American diet. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 1715–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manach, C.; Scalbert, A.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Polyphenols: Food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 727–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, M.H. Significance of Dietary Antioxidants for Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 13, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, M.; Melander, M.; Pojmark, P.; Larsson, H.; Bülow, L.; Hofvander, P. Targeted gene suppression by RNA interference: An efficient method for production of high-amylose potato lines. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 123, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgos, G.; Muñoa, L.; Sosa, P.; Bonierbale, M.; zum Felde, T.; Díaz, C. In vitro Bioaccessibility of Lutein and Zeaxanthin of Yellow Fleshed Boiled Potatoes. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013, 68, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.R. Antioxidants in potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 2005, 82, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stushnoff, C.; Holm, D.; Thompson, M.D.; Jiang, W.; Thompson, H.J.; Joyce, N.I.; Wilson, P. Antioxidant Properties of Cultivars and Selections from the Colorado Potato Breeding Program. Am. J. Potato Res. 2008, 85, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitchumroonchokchai, C.; Diretto, G.; Parisi, B.; Giuliano, G.; Failla, M.L. Potential of golden potatoes to improve vitamin A and vitamin E status in developing countries. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Külen, O.; Stushnoff, C.; Holm, D.G. Effect of cold storage on total phenolics content, antioxidant activity and vitamin C level of selected potato clones. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2437–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamar, M.C.; Tosetti, R.; Landahl, S.; Bermejo, A.; Terry, L.A. Assuring Potato Tuber Quality during Storage: A Future Perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öhrvik, V.; Mattisson, I.; Wretling, S.; Åstrand, C. Potato—Analysis of Nutrients; National Food Administration: Uppsala, Sweden, 2010.

- Mozaffarian, D.; Hao, T.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in Diet and Lifestyle and Long-Term Weight Gain in Women and Men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, S.A.; Jeffery, R.W.; Forster, J.L.; McGovern, P.G.; Kelder, S.H.; Baxter, J.E. Predictors of weight change over two years among a population of working adults: The Healthy Worker Project. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1994, 18, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linde, J.A.; Utter, J.; Jeffery, R.W.; Sherwood, N.E.; Pronk, N.P.; Boyle, R.G. Specific food intake, fat and fiber intake, and behavioral correlates of BMI among overweight and obese members of a managed care organization. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Halkjær, J.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Sørensen, T.I.A. Dietary Predictors of 5-Year Changes in Waist Circumference. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1356–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkjaer, J.; Sørensen, T.I.A.; Tjønneland, A.; Togo, P.; Holst, C.; Heitmann, B.L. Food and drinking patterns as predictors of 6-year BMI-adjusted changes in waist circumference. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, R.W.; Forster, J.L.; French, S.A.; Kelder, S.H.; Lando, H.A.; McGovern, P.G.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Baxter, J.E. The Healthy Worker Project: A work-site intervention for weight control and smoking cessation. Am. J. Public Health 1993, 83, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjønneland, A.; Olsen, A.; Boll, K.; Stripp, C.; Christensen, J.; Engholm, G.; Overvad, K. Study design, exposure variables, and socioeconomic determinants of participation in Diet, Cancer and Health: A population-based prospective cohort study of 57,053 men and women in Denmark. Scand. J. Public Health 2007, 5, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurses’ Health Study. Available online: http://www.nurseshealthstudy.org/ (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. Available online: https://sites.sph.harvard.edu/hpfs/ (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Villegas, R.; Liu, S.; Gao, Y.-T.; Yang, G.; Li, H.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X.O. Prospective Study of Dietary Carbohydrates, Glycemic Index, Glycemic Load, and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Middle-aged Chinese Women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 2310–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodge, A.M.; English, D.R.; O’Dea, K.; Giles, G.G. Glycemic index and dietary fiber and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2701–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Serdula, M.; Janket, S.-J.; Cook, N.R.; Sesso, H.D.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E. A prospective study of fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 2993–2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraki, I.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Potato Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.H.; Brand Miller, J.C.; Petocz, P. Interrelationships among postprandial satiety, glucose and insulin responses and changes in subsequent food intake. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 50, 788–797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Erdmann, J.; Hebeisen, Y.; Lippl, F.; Wagenpfeil, S.; Schusdziarra, V. Food intake and plasma ghrelin response during potato-, rice- and pasta-rich test meals. Eur. J. Nutr. 2007, 46, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeman, M.; Östman, E.; Björck, I. Glycaemic and satiating properties of potato products. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geliebter, A.; Lee, M.I.-C.; Abdillahi, M.; Jones, J. Satiety following Intake of Potatoes and Other Carbohydrate Test Meals. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 62, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akilen, R.; Deljoomanesh, N.; Hunschede, S.; Smith, C.E.; Arshad, M.U.; Kubant, R.; Anderson, G.H. The effects of potatoes and other carbohydrate side dishes consumed with meat on food intake, glycemia and satiety response in children. Nutr. Diabetes 2016, 6, e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Toledo, C.; Kurilich, A.C.; Re, R.; Wickham, M.S.J.; Chambers, L.C. Satiety Impact of Different Potato Products Compared to Pasta Control. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2016, 35, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geliebter, A. Gastric distension and gastric capacity in relation to food intake in humans. Physiol. Behav. 1988, 44, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.H.; Miller, J.C.; Petocz, P.; Farmakalidis, E. A satiety index of common foods. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 49, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rolls, B.J.; Bell, E.A.; Thorwart, M.L. Water incorporated into a food but not served with a food decreases energy intake in lean women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster-Powell, K.; Miller, J.B. International tables of glycemic index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 62, 871S–890S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halton, T.L.; Willett, W.C.; Liu, S.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Hu, F.B. Potato and French fry consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 83, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmerón, J.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Wing, A.L.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 1997, 277, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, A.W.; Petocz, P.; McMillan-Price, J.; Flood, V.M.; Prvan, T.; Mitchell, P.; Mitchell, P.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk—A meta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Clin Nutr. 2008, 87, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oba, S.; Nanri, A.; Kurotani, K.; Goto, A.; Kato, M.; Mizoue, T.; Noda, M.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; Japan Public Health Center-Based Prospective Study Group. Dietary glycemic index, glycemic load and incidence of type 2 diabetes in Japanese men and women: The Japan public health center-based prospective study. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ek, K.L.; Wang, S.; Copeland, L.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Discovery of a low-glycaemic index potato and relationship with starch digestion in vitro. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin Ek, K.; Wang, S.; Brand-Miller, J.; Copeland, L. Properties of starch from potatoes differing in glycemic index. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2509–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, F.S.; Foster-Powell, K.; Brand-Miller, J.C. International Tables of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values: 2008. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2281–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, C.J.; Lightowler, H.J.; Kendall, F.L.; Storey, M. The impact of the addition of toppings/fillings on the glycaemic response to commonly consumed carbohydrate foods. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hätönen, K.A.; Virtamo, J.; Eriksson, J.G.; Sinkko, H.K. Protein and fat modify the glycaemic and insulinaemic responses to a mashed potato-based meal. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 2011 106, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Ruesten, A.; Feller, S.; Bergmann, M.M.; Boeing, H. Diet and risk of chronic diseases: Results from the first 8 years of follow-up in the EPIC-Potsdam study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadnejad, H.; Teymoori, F.; Asghari, G.; Mirmiran, P.; Azizi, F. The Association of Potato Intake with Risk for Incident Type 2 Diabetes in Adults. Can. J. Diabetes 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salmerón, J.; Ascherio, A.; Rimm, E.B.; Colditz, G.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Jenkins, D.J.; Stampfer, M.J.; Wing, A.L.; Willett, W.C. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of NIDDM in men. Diabetes Care 1997, 20, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Available online: https://www.cancervic.org.au/research/epidemiology/health_2020/health2020-overview (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Women’s Health Study. Available online: http://whs.bwh.harvard.edu/ (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Zheng, W.; Chow, W.-H.; Yang, G.; Jin, F.; Rothman, N.; Blair, A.; Li, H.L.; Wen, W.; Ji, B.T.; Li, Q.; et al. The Shanghai Women’s Health Study: Rationale, Study Design, and Baseline Characteristics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 162, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPIC Centres—GERMANY. Available online: http://epic.iarc.fr/centers/germany.php (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Hosseinpanah, F.; Rambod, M.; Reza Ghaffari, H.R.; Azizi, F. Predicting isolated postchallenge hyperglycaemia: A new approach; Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS). Diabet. Med. 2006, 23, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Potato consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: 2 prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshipura, K.J.; Ascherio, A.; Manson, J.E.; Stampfer, M.J.; Rimm, E.B.; Speizer, F.E.; Hennekens, C.H.; Spiegelman, D.; Willett, W.C. Fruit and vegetable intake in relation to risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA 1999, 282, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Zhuang, P.; Jiao, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Potato consumption is prospectively associated with risk of hypertension: An 11.3-year longitudinal cohort study. Clin Nutr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgi, L.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Forman, J.P. Potato intake and incidence of hypertension: Results from three prospective US cohort studies. BMJ 2016, 353, i2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, E.A.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Corella, D.; Ros, E.; Fitó, M.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A.; Estruch, R.; Arós, F.; Fiol, M.; et al. Potato Consumption Does Not Increase Blood Pressure or Incident Hypertension in 2 Cohorts of Spanish Adults. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinson, J.A.; Demkosky, C.A.; Navarre, D.A.; Smyda, M.A. High-Antioxidant Potatoes: Acute in Vivo Antioxidant Source and Hypotensive Agent in Humans after Supplementation to Hypertensive Subjects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6749–6754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safar, M.E. Systolic blood pressure, pulse pressure and arterial stiffness as cardiovascular risk factors. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2001, 10, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, C.; Smail, N.F.; Almoosawi, S.; McDougall, G.J.M.; Al-Dujaili, E.A.S. Antioxidant Rich Potato Improves Arterial Stiffness in Healthy Adults. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2018, 73, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, A.; Welch, A.A.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J.; Kay, C.; Minihane, A.-M.; Chowienczyk, P.; Jiang, B.; Cecelja, M.; Spector, T.; Macgregor, A.; et al. Higher anthocyanin intake is associated with lower arterial stiffness and central blood pressure in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Remón, A.; Zamora-Ros, R.; Rotchés-Ribalta, M.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; et al. Total polyphenol excretion and blood pressure in subjects at high cardiovascular risk. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2011, 21, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aburto, N.J.; Hanson, S.; Gutierrez, H.; Hooper, L.; Elliott, P.; Cappuccio, F.P. Effect of increased potassium intake on cardiovascular risk factors and disease: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2013, 346, f1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, M.P.; Rodrigues, S.L.; Mill, J.G. High salt intake as a multifaceted cardiovascular disease: New support from cellular and molecular evidence. Heart Fail. Rev. 2015, 20, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PREDIMED Trial. Available online: http://www.predimed.es/introduction.html (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Martínez-González, M.A. The SUN cohort study (Seguimiento University of Navarra). Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS). Available online: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/china (accessed on 16 August 2018).

| Nutrient | Raw (Flesh and Skin) | Boiled (Flesh Only) Cooked Without Skin | Boiled (Flesh Only) Cooked in Skin | Baked (Flesh and Skin) | Microwaved (Flesh and Skin) | Oven-Baked Chips 1 | Fried Chips 2 | Daily RNI; (M/F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water (g) | 79.3 | 77.5 | 77.0 | 74.9 | 72.0 | 64.4 | 38.6 | - |

| Energy (kcal) | 77 | 86 | 87 | 93 | 105 | 158 | 312 | - |

| Protein (g) | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.3 | - |

| Fat (g) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 14.7 | - |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 17.5 | 20.0 | 20.1 | 21.2 | 24.2 | 25.6 | 41.4 | - |

| Fibre * (g) | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 3.8 | - |

| Minerals | ||||||||

| Calcium (mg) | 12 | 8 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 18 | 700 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.81 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 1.08 | 1.24 | 0.57 | 0.81 | 8.7/14.8 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 23 | 20 | 22 | 28 | 27 | 24 | 35 | 300/270 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 57 | 40 | 44 | 70 | 105 | 87 | 125 | 550 |

| Potassium (mg) | 425 | 328 | 379 | 535 | 447 | 478 | 579 | 3500 |

| Sodium (mg) | 6 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 324 ** | 210 ** | 1600 |

| Zinc (mg) | 0.30 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 9.5/7.0 |

| Vitamins | ||||||||

| Vitamin C (mg) | 19.7 | 7.4 | 13.0 | 9.6 | 15.1 | 8.7 | 4.7 | 40 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 0.081 | 0.098 | 0.106 | 0.064 | 0.120 | 0.130 | 0.170 | 1.0/0.8 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 0.032 | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.048 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.039 | 1.3/1.1 |

| Niacin (mg) | 1.061 | 1.312 | 1.439 | 1.410 | 1.714 | 2.077 | 3.004 | 17/13 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.298 | 0.269 | 0.299 | 0.311 | 0.344 | 0.261 | 0.372 | 1.4/1.2 |

| Folate (µg) | 15 | 9 | 10 | 28 | 12 | 23 | 30 | 200 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.5 |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 700/600 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.39 | 1.67 | - |

| Vitamin D (µg) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 10 |

| Vitamin K (µg) | 2.0 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 7.4 | 11.2 | - |

| Reference | Study Type; Follow-Up/Duration | n (%F); BMI; Age (years); Criteria | Exposure; Assessment Method | Results | Potato Categories | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French et al., 1994 [55] | Cross-sectional and prospective cohort (two years) | 3552 (53.9%) Normal weight to obese 37.3 ± 10.7 years (F) 39.1 ± 9.8 years (M) | Participating in a workplace weight loss intervention FFQ (18 items) | A trend for an association (p = 0.06) between consumption of French fries/fried potatoes and higher bodyweight in women at baseline Increased consumption of French fries associated with weight gain in women | French fries and fried potatoes in a single category; no other potatoes measured | Data from the Healthy Worker Project [59] Participants were fully clothed, including shoes, for weight measurement. Time of day was not standardised. FFQ contained only 15 highest contributors to energy and fat intake; fruit and vegetable intake was not assessed. |

| Halkjaer et al., 2004 [58] | Cohort (six years) | 2300 (49.2%) Normal weight to obese 30–60 years Of Danish origin | Habitual diet FFQ (26 items) | A weak inverse association between potato consumption and waist circumference; insignificant after adjustment for changes in obesity | Potatoes (unspecified) | Data from the MONICA1 study Intake remained largely unchanged over the time period measured |

| Linde et al., 2006 [56] | Cross-sectional and prospective cohort (2 years) | 1801 (71.8%) Overweight and obese (BMI > 27) >18 years | Participating in weight loss intervention Block Screening Questionnaires for Fat (15 Items) and Fruit/Vegetable/Fibre (nine items) Intake | Consumption of French fries associated with higher BMI in women, but not men at baseline Increased consumption of French fries associated with increased BMI over two years for men and women No association between potatoes and BMI at baseline or over the course of the intervention | Potatoes; French fries | |

| Halkjaer et al., 2009 [57] | Cohort (five years) | 42,696 (52.9%) BMI 20–33.5 50–64 years | Habitual diet FFQ (192 items, 21 groups) | Energy intake from potatoes was associated with five year increase in waist circumference in women | Potatoes (not including French fries) | Data from the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study [60] French fries were incorporated into a Snack Foods group, potatoes were in a group of their own. All analysis by group, not individual food item. |

| Mozaffarian et al., 2011 [54] | Three cohorts (four year intervals) | 120,877 (81.3%) Non-obese at baseline 18–64 years Energy intake 900–3500 kcal/day | Habitual diet FFQ (61/131 items) | Four year weight change was positively associated with potato intake (all categories) | Total potato intake; Boiled, baked or mashed; French fries; Potato chips | Data from the Nurses’ Health Study I and II [61] and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study [62] |

| Reference | Participants | Study Type | Test Meals | Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holt et al., 1996 [67] | n = 11–13 per group BMI 22.7 ± 0.4 22.1 ± 2.9 years | Crossover | 1000 kJ portions of 38 test foods split into food groups, carbohydrate-rich group included. Along with 220 mL water. White bread as reference food. | Seven-point scale for satiety ratings | Boiled potatoes had the highest satiety score of all foods. An inverse association between satiety score and subsequent ad libitum energy intake was observed. |

| Erdmann et al., 2007 [68] | 11 M BMI 23.5 ± 0.5 24.4 ± 0.3 years | Crossover | 150 g lean pork steak, served with ad libitum amount of boiled white pasta, boiled white rice or boiled white potatoes, all in tomato sauce. Participants asked to consume foods until comfortably satiated. Ad libitum sandwich meal provided 4 h later. | VAS scores for hunger and satiety every 15 min | Comparable amounts of potato, pasta and rice consumed at first meal (353–372 g), but energy intake significantly lower for potato meal (2177 kJ) than rice (2829 kJ) and pasta (3174 kJ). Greater satiety and less hunger following pasta and rice meals during hour 4. No difference in energy consumption at second ad libitum meal (+4 h) No differences in satiety and hunger following second meal. |

| Leeman et al., 2008 [69] Study 1 | 9 M, 4 F BMI 21.8 ± 3.1 19–27 years | Crossover | Isoenergetic 1000 kJ portions of boiled potatoes, French fries or instant mashed potatoes (reconstituted with 200 or 330 g water), providing 32.5–50.3 g available CHO, all served with 250 water or milk/water mix and 150 mL tea/coffee. | Nine-point scale (painfully hungry–full to nausea) | French fries produced a lower satiety AUC than boiled potatoes over 4 h and lower satiety AUC than the small portion of mashed potato over 0–70 min. |

| Leeman et al., 2008 [69] Study 2 | 6 M, 8 F BMI 21.9 ± 2.0 20–28 years | Crossover | 50 g available CHO portions of French fries and boiled potatoes, with or without 15.4 g sunflower oil (963–534 kJ), white wheat bread reference, all served with 150 water and 150 mL tea/coffee. | Nine-point scale (painfully hungry–full to nausea) | No significant differences between meals. |

| Geliebter et al., 2013 [70] | 6 M, 6 F BMI 22.4 ± 2.0 22–30 years | Crossover | 240 kcal portions (50 g CHO) of peeled baked potato, instant mashed potato, steamed brown rice and boiled pasta. White bread as control (273 kcal, 50 g CHO). Variable amount of water (180–363 g) served on the side to bring total water content of each meal to 400 g. | Scales for hunger, fullness, desire to eat and prospective consumption | Both potato meals reduced appetite compared to pasta and rice. No differences between meals on subsequent (2 h) energy intake. |

| Akilen et al., 2016 [71] | Study 1: 12 M, 8 F Study 2: 6 M, 6 F 11–12 years (children) normal weight | Crossover | 100 g meatballs, served with ad libitum boiled mashed potatoes (from frozen, served with milk and butter), pasta (with milk, butter and cheese powder), boiled white rice (with butter and rice seasoning), oven fries or French fries. All served 4 h after a standardised breakfast. | VAS for satiety ratings | A smaller amount of oven fries and French fries was consumed than pasta. Energy intake was lower for boiled mashed potato than all other meals. No difference between meals for mean appetite scores until adjusted for energy intake. Adjusted post-meal appetite scores were lower for boiled mashed potatoes than other test meals. |

| Diaz-Toledo et al., 2016 [72] | 16 M, 17 F BMI 22.7 ± 0.3 34.1 ± 2.4 years | Crossover | 858 kJ portions of French fries (deep-fried from frozen), baked potato (pre-prepared, microwaved from frozen), mashed potato (pre-prepared, microwaved from chilled), or potato wedges (microwaved and served chilled). Pasta (boiled) as control. All served with meatballs in tomato sauce, salad and Caesar dressing (total energy from meal, 1883 kJ). All served 3 h after a standardized, personalised breakfast. Ad libitum sandwich and yoghurt meal provided 4 h after test meal. | VAS for satiety ratings (hunger, fullness, desire to eat and prospective consumption) | Higher satiety ratings (4 h AUC) for French fries, compared to pasta. Each potato meal compared to pasta meal only; no comparisons performed between potato-based meals. No difference in energy consumption at second ad libitum meal (+4 h). |

| Potato Variety and Cooking Method | Glycaemic Index | Glycaemic Load (150 g Portion) | Available CHO (g per 150 g Portion) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charlotte (waxy), boiled 15 min | 66 | 15 | 23 |

| Nicola (waxy), boiled 15 min | 58–59 | 9 | 16 |

| Carisma (waxy), boiled 8–9 min | 53 | 8 | 16 |

| Desiree, boiled 35 min | 101 | 17 | 17 |

| Pontiac, boiled 35 min | 88 | 16 | 18 |

| Russet Burbank, unpeeled, microwaved for 18 min | 77 ± 9 | 19 | 25 |

| White with skin, baked | 69 | 19 | 27 |

| Instant mashed potato | 79–97 | 16–19 | 20 |

| Desiree, mashed | 102 | 26 | 26 |

| Pontiac, mashed | 91 | 18 | 20 |

| French fries, baked 15 min | 64 | 21 | 32 |

| Irish potato, peeled, fried in oil | 70 | 21 | 30 |

| Reference | Study Type; Follow-Up/Duration | n (%F); BMI (kg/m2); Age (years); Criteria | Exposure; Assessment Method | Results | Potato Categories | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmerón et al., 1997 [88] | Cohort (six years) | 42,759 (0%); normal weight to obese; 40–75 years Energy intake 400-4200 kcal/day | Habitual diet FFQ (131 items) | Consumption of French fries, but not total potato intake, was associated with increased risk of T2DM | Cooked potato; French fries | Data from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study [62] |

| Salmeron et al., 1997 [78] | Cohort (six years) | 65,173 (100%); normal weight to obese; 40–65 years Energy intake 600–3502 kcal/day | Habitual diet FFQ (134 items) | Intake of both total potatoes and French fries was associated with increased risk of T2DM | Cooked potato; French fries | Data from the Nurses’ Health Study [61] |

| Hodge et al., 2004 [64] | Cohort (four years) | 31,641 (59%); normal weight to obese; 27–75 years | Habitual diet FFQ (121 items) | Total potato intake was not associated with risk of T2DM Total carbohydrate intake was inversely associated with T2DM incidence High dietary GI was associated with increased risk of T2DM | Total potato intake | Data from The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study [89] |

| Liu et al., 2004 [65] | Cohort (8 to 9 years) | 38,018 (100%); normal weight to obese; ≥45 years | Habitual diet FFQ (131 items) | Total potato intake was not associated with risk of T2DM | Total potato intake | Data from the Women’s Health Study [90] |

| Halton et al., 2006 [77] | Cohort (20 years) | 84,555 (100%); normal weight to obese; 30–55 years at baseline; Energy intake 500–3500 kcal/day | Habitual diet FFQ (61 items at baseline, rising to 131 items), repeated assessment | Baked or mashed potato intake was associated with risk of T2DM in obese women only Intake of French fries was associated with increased risk of T2DM for all women | French fries; Baked or mashed | Data from the Nurses’ Health Study [61] Potato and French fries consumption patterns did not change over time |

| Villegas et al., 2007 [63] | Cohort (4.6 years) | 64,227 (100%); normal weight to obese; 40–70 years | Habitual diet FFQ (77 food items/groups) | Potato consumption associated with lower risk of T2DM | Total potato intake | Data from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study [91] Study population did not consume much potato (median intake 8.1 g/day); their main CHO was rice |

| Von Ruesten et al., 2013 [86] | Cohort (eight years) | 23,531 (61%); normal weight to obese; 35–65 years Energy intake 800–6000 kcal/day | Habitual diet FFQ (148 food items) | No associations between potato or fried potato consumption and T2DM risk | Potatoes (potatoes, mashed, potato dumpling, potato salad); Fried potatoes (French fries, croquettes, fried potatoes, potato pancake) | Data from the EPIC Potsdam Study [92] |

| Muraki et al., 2016 [66] | Three cohorts (four years) | 199,181 (80%) Normal weight to obese; 40–75 years; | Habitual diet FFQ (61/131 items) | Consumption of potatoes, especially French fries was associated with increased risk of T2DM | Total potato intake; Boiled, baked or mashed; French fries | Data from the Nurses’ Health Study I and II [61] and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study [62] |

| Farhadnejad et al., 2018 [87] | Cohort (six years) | 1981 (53.8%) normal weight to obese 38.9 ± 13.4 years | Total potato and boiled potato consumption both associated with lower risk of T2DM | Total potato intake; Boiled potatoes;Fried potatoes | Data from the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study [93] Median intake 22.4 g/day |

| Reference | Study Type; Follow-Up/Duration | n (%F); BMI; Age (years); Criteria | Exposure; Assessment Method | Results | Cooking Methods | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joshipura et al., 1999 [95] | Two cohorts (NHS: eight years; HPFS: 14 years) | 114,276 (66%); mean BMI 24.3–25.45 kg/m2; M: 40–75 years F: 34–59 years; CVD-, cancer- and T2DM-free at baseline | Habitual diet FFQ (61/131 items) | No association between potato consumption and ischemic stroke risk | Not Specified | Data from the Nurses’ Health Study I and II [61] and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study [62] |

| Larsson et al., 2016 [94] | Two cohorts (13 years) | 69,313 (47.3%); M: 45–79 years F: 49–83 years; CVD-, cancer- and T2DM-free at baseline | Habitual diet FFQ (96 items) | Neither total potato consumption nor any individual cooking method was associated with risk of major CVD events (myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke) or mortality from CVD | Total potatoes; Boiled potatoes; Fried potatoes; French fries | Data from the Cohort of Swedish Men and the Swedish Mammography Cohort Median total potato consumption 4.5–5.5 times/week, mainly from boiled potatoes (3.5 times/week) |

| Borgi et al., 2016 [97] | Three cohorts (max 24–34 years) Health questionnaires every two years | 187,453 (80.4%) Non-hypertensive at baseline BMI 20.9–31.8 kg/m2 F: 25–55 years M: 40–75 years | Habitual diet FFQ (61/131 items) | ≥1 serving/day of potato (all types) associated with increased risk of hypertension, compared to <1 serving/month ≥4 servings/week of boiled, baked or mashed potatoes associated with increased risk of hypertension in women but not men, compared to <1 serving/month ≥4 servings/week French fries associated with increased risk of hypertension, compared to <1 serving/month | Total potato intake; Boiled, baked or mashed; French fries; Potato chips | Data from the Nurses’ Health Study I and II [61] and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study [62] |

| Hu et al., 2017 [98] | 2 cohorts 4 and 6–7 years follow-ups) | PREDIMED: 6940 55–80 years CVD free, but at high risk (T2DM or ≥3 of: smoking, hypertension, high LDL, low HDL, overweight, family history of CVD) SUN project: 13,837 M: 42.7 ± 13.3 years F: 35.1 ± 10.7 years | PREDIMED: Mediterranean diet FFQ (137 items) SUN: Habitual diet FFQ (136 items) | Total potato intake not associated with change in BP or incidence of hypertension over 4 years | PREDIMED: Potato chips (crisps), homemade fries, cooked or boiled potatoes SUN: Fried potatoes, cooked or roasted potatoes | Data from the PREDIMED [106] and SUN [107] cohorts |

| Huang et al., 2018 [96] | Cohort Mean 11.3 years | 11,763 (54.6%) 20–93 years No hypertension, infarction or diabetes at baseline | Habitual diet, three day dietary recall | Sweet potato associated with HT in urban residents Potatoes (p = 0.1225), stir-fried potatoes (p = 0.2168) and non-stir-fried potatoes (p = 0.0456) all associated with HT When non-potato consumers were excluded, higher consumption of total potatoes and stir-fried potatoes associated with lower risk of HT | Total potatoes; Sweet potatoes; Stir-fried potatoes; Non stir-fried potatoes | Data from the China Health and Nutrition Survey [108] Urban residents more likely to consume sweet potato in snack form (fried chips, sugar-cured fries) Rice was the main starchy CHO in the diet, potato consumption was much lower than Western countries; potatoes were more often consumed as a side dish |

| Reference | Study Type; Follow-up/Duration | n (F); BMI; age (years); Criteria | Exposure; Assessment Method | Results | Cooking Methods | Potato Type | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinson et al., 2012 [99] | 1. RCT: Single meal 2. Supplementation: Crossover (four weeks) | 8 (1); 5 normal weight, 2 overweight, 1 obese; 23 ± 9 years; Healthy 18 (11); 5 normal weight, 6 overweight, 7 obese; 54 ± 10 years; 14/18 hypertensive; 13/18 taking BP lowering medication | 6–8 small potatoes (~138 g), microwaved; Biscuit containing equivalent amount of potato starch served as control; Plasma samples (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 h) 24 h urine collection (urine polyphenols), pre- and post-study 6–8 small potatoes, microwaved, twice a day (lunch and dinner); No potatoes consumed on alternate arm; (BP, body weight, glucose, HDL, TAG, TC) pre/post trial | Non-significantly lower plasma antioxidant capacity following control meal, compared to potatoes (p = 0.11) Urine polyphenols increased by 92% following potato consumption and decreased by 3.5% following control biscuit (p = 0.09 for trend) 4 mmHg reduction in DBP following potato supplementation (p < 0.01); No effect on plasma glucose, HbA1c or lipids No effect on SBP or body weight | Microwaved, consumed with skins | Purple majesty (pigmented potato) | Participants followed a low polyphenol diet for three days prior to the acute study |

| Tsang et al., 2018 [101] | RCT (14 days, with seven days washout between treatments) | 14 (8F); BMI: 19.4–31.2 kg/m2 (11 normal weight, 2 overweight, 1 obese) 20–55 years; Healthy; Normotensive | 200 g/day of PM potato versus white potato control; PWV, BP, bodyweight Plasma samples (TAG, HDL, LDL, TC, CRP, insulin, glucose) | Consumption of PM potatoes, but not white potatoes, significantly reduced PWV; No changes in any other measure for either PM or white potato | Boiled with skin | Purple Majesty (PM) | PM potatoes contain significantly higher amounts of anthocyanins than white potatoes (control); Participants were forbidden certain high-polyphenol foods and drinks and advised to limit fruit, vegetable and potato intake during the study |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Robertson, T.M.; Alzaabi, A.Z.; Robertson, M.D.; Fielding, B.A. Starchy Carbohydrates in a Healthy Diet: The Role of the Humble Potato. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111764

Robertson TM, Alzaabi AZ, Robertson MD, Fielding BA. Starchy Carbohydrates in a Healthy Diet: The Role of the Humble Potato. Nutrients. 2018; 10(11):1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111764

Chicago/Turabian StyleRobertson, Tracey M., Abdulrahman Z. Alzaabi, M. Denise Robertson, and Barbara A. Fielding. 2018. "Starchy Carbohydrates in a Healthy Diet: The Role of the Humble Potato" Nutrients 10, no. 11: 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111764

APA StyleRobertson, T. M., Alzaabi, A. Z., Robertson, M. D., & Fielding, B. A. (2018). Starchy Carbohydrates in a Healthy Diet: The Role of the Humble Potato. Nutrients, 10(11), 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111764