Herbs and Spices in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review of Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

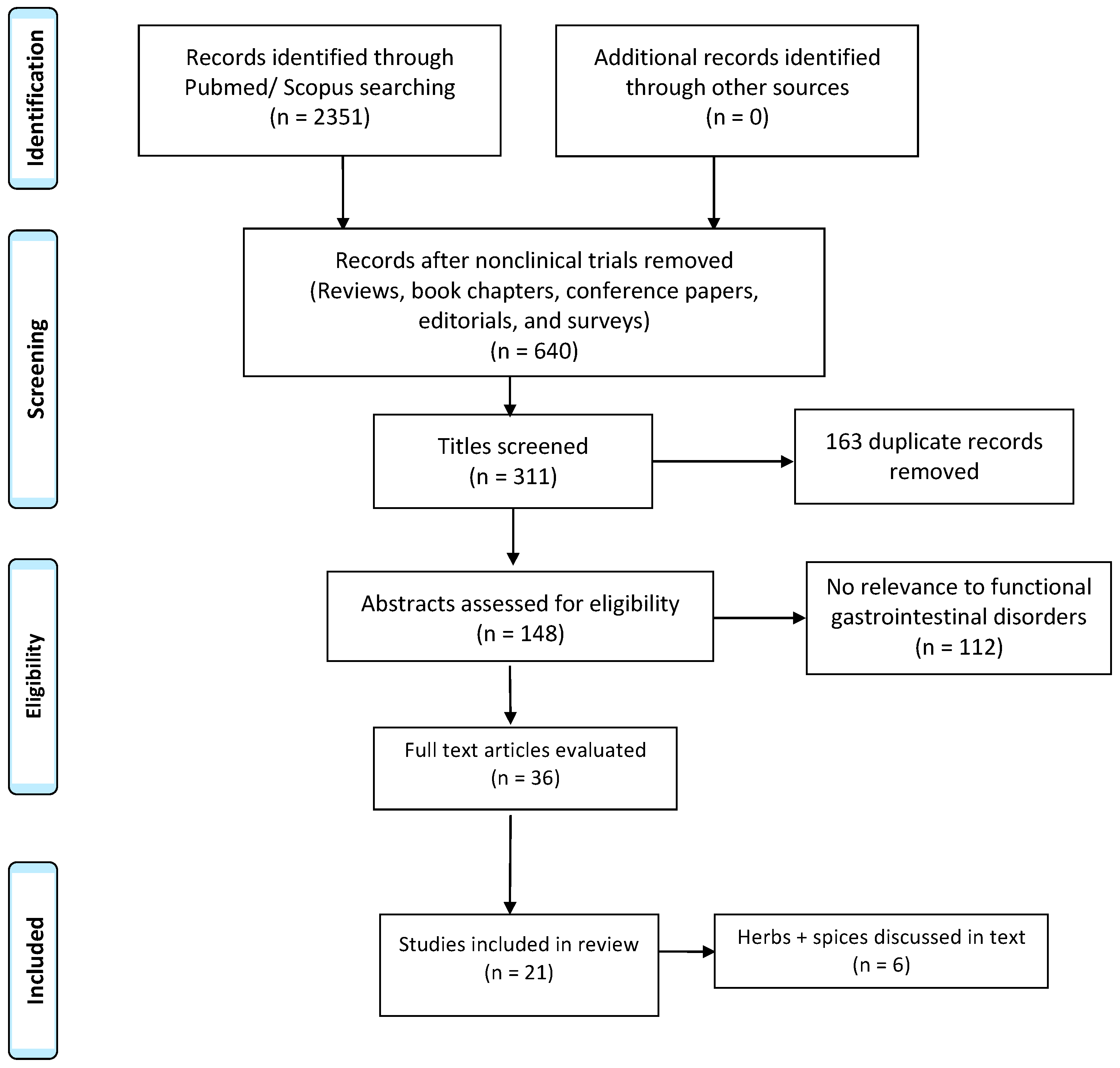

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Peppermint Oil

3.2. STW 5 (Iberogast)

3.3. Turmeric

3.4. Cannabis

3.5. Aloe Vera

3.6. Ginger

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carlson, M.J.; Moore, C.E.; Tsai, C.M.; Shulman, R.J.; Chumpitazi, B.P. Child and parent perceived food-induced gastrointestinal symptoms and quality of life in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beinvogl, B.; Burch, E.; Snyder, J.; Schechter, N.; Hale, A.; Okazaki, Y.; Paul, F.; Warman, K.; Nurko, S. Multidisciplinary treatment of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders results in improved pain and functioning. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.W.; Bendo, C.B.; Nurko, S.; Shulman, R.J.; Self, M.M.; Franciosi, J.P.; Saps, M.; Pohl, J.F. Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Gastrointestinal Symptoms Module Testing Study Consortium Health-related quality of life in pediatric patients with functional and organic gastrointestinal diseases. J. Pediatr. 2015, 166, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, T.; Friesen, C.; Schurman, J.V. Classification of pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders related to abdominal pain using Rome III vs. Rome IV criterions. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, E.; Nurko, S. Functional abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome in children and adolescents. Therapy. 2011, 8, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pike, A.; Etchegary, H.; Godwin, M.; McCrate, F.; Crellin, J.; Mathews, M.; Law, R.; Newhook, L.A.; Kinden, J. Use of natural health products in children: Qualitative analysis of parents’ experiences. Can. Fam. Physician 2013, 59, e372–e378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Halmos, E.P.; Power, V.A.; Shepherd, S.J.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate, L.; de Bari, O.; Lembo, A.; Ballou, S. Irritable bowel syndrome and diet. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2017, 5, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosengarten, F., Jr. The Book of Spices, 1st ed.; Jove Publ. Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1969; pp. 23–96. [Google Scholar]

- Grigoleit, H.G.; Grigoleit, P. Gastrointestinal clinical pharmacology of peppermint oil. Phytomedicine 2005, 12, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, M.; Bonorris, G.G.; Chow, E.J.; Lin, H.C. Peppermint oil improves the manometric findings in diffuse esophageal spasm. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2001, 33, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.M.; Kline, J.J.; Palma, J.D.; Barbero, G.J. Enteric-coated, pH-dependent peppermint oil capsules for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in children. J. Pediatr. 2001, 138, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgarshirazi, M.; Shariat, M.; Dalili, H. Comparison of the effects of pH-Dependent peppermint oil and synbiotic lactol (Bacillus coagulans + Fructooligosaccharides) on childhood functional abdominal pain: A randomized placebo-controlled study Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, G.; Coraggio, D.; Berardinis, G.D.; Spezzaferro, M.; Grossi, L.; Marzio, L. Peppermint oil (Mintoil®) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective double blind placebo-controlled randomized trial. Dig. Liver Dis. 2007, 39, 530–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merat, S.; Khalili, S.; Mostajabi, P.; Ghorbani, A.; Ansari, R.; Malekzadeh, R. The effect of enteric-coated, delayed-release peppermint oil on irritable bowel syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.S.; Roy, P.K.; Miah, A.R.; Mollick, S.H.; Khan, M.R.; Mahmud, M.C.; Khatun, S. Efficacy of Peppermint oil in diarrhea predominant IBS – A double blind randomized placebo-controlled study. Mymensingh Med. J. 2013, 22, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cash, B.D.; Epstein, M.S.; Shah, S.M. A novel delivery system of peppermint oil is an effective therapy for irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, G.; Shah, A.; Koloski, N.; Funk, P.; Stracke, B.; Köhler, S.; Holtmann, G. A randomized placebo-controlled trial on the effects of Menthacarin, a proprietary peppermint- and caraway-oil-preparation, on symptoms and quality of life in patients with functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, B.; Kuntz, H.D.; Kieser, M.; Köhler, S. Efficacy of a fixed peppermint oil/caraway oil combination in non-ulcer dyspepsia. Arzneimittelforschung 1996, 46, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kligler, B.; Chaudhary, S. Peppermint oil. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 75, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malfertheiner, P. STW 5 (Iberogast) therapy in gastrointestinal functional disorders. Dig. Dis. 2017, 35, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundermann, K.J.; Vinson, B. Die funktionelle Dyspepsie bei Kindern–eine retrospektive Studie mit einem Phytopharmakon. Päd 2004, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vinson, B.R.; Radke, M. The herbal preparation STW 5 for the treatment of functional gastrointestinal diseases in children aged 3–14 years—A prospective non-interventional study. Gastroenterology 2011, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madisch, A.; Holtmann, G.; Plein, K.; Hotz, J. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with herbal preparations: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 19, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Arnim, U.; Peitz, U.; Vinson, B.; Gundermann, K.-J.; Malfertheiner, P. STW 5, a phytopharmacon for patients with functional dyspepsia: Results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 102, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braden, B.; Caspary, W.; Börner, N.; Vinson, B.; Schneider, A.R.J. Clinical effects of STW 5 (Iberogast®) are not based on acceleration of gastric emptying in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2009, 21, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raedsch, R.; Vinson, B.; Ottillinger, B.; Holtmann, G. Early onset of efficacy in patients with functional and motility-related gastrointestinal disorders. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2018, 168, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbar, M.U.; Rehman, K.; Zia, K.M.; Qadir, M.I.; Akash, M.S.H.; Ibrahim, M. Critical review on curcumin as a therapeutic agent: From traditional herbal medicine to an ideal therapeutic agent. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2018, 28, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Turmeric, the Golden Spice: From Traditional Medicine to Modern Medicine. In Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects, 2rd ed.; Benzie, I.F.F., Wachtel-Galor, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Farhood, B.; Mortezaee, K.; Goradel, N.H.; Khanlarkhani, N.; Salehi, E.; Nashtaei, M.S.; Najafi, M.; Sahebkar, A. Curcumin as an anti-inflammatory agent: Implications to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahebkar, A. Are curcuminoids effective c-reactive protein-lowering agents in clinical practice? evidence from a meta-analysis. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friesen, C.; Singh, M.; Singh, V.; Schurman, J.V. An observational study of headaches in children and adolescents with functional abdominal pain: Relationship to mucosal inflammation and gastrointestinal and somatic symptoms. Medicine 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leamy, A.W.; Shukla, P.; McAlexander, M.A.; Carr, M.J.; Ghatta, S. Curcumin ((E,E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione) activates and desensitizes the nociceptor ion channel TRPA1. Neurosci. Lett. 2011, 503, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, F.N.; Gazal, M.; Bastos, C.R.; Kaster, M.P.; Ghisleni, G. Curcumin in depressive disorders: An overview of potential mechanisms, preclinical and clinical findings. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 784, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windgassen, S.; Moss-Morris, R.; Chilcot, J.; Sibelli, A.; Goldsmith, K.; Chalder, T. The journey between brain and gut: A systematic review of psychological mechanisms of treatment effect in irritable bowel syndrome. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 701–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundy, R.; Walker, A.F.; Middleton, R.W.; Booth, J. Turmeric extract may improve irritable bowel syndrome symptomology in otherwise healthy adults: A. pilot study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2004, 10, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkhaus, B.; Hentschel, C.; Von Keudell, C.; Schindler, G.; Lindner, M.; Stützer, H.; Kohnen, R.; Willich, S.N.; Lehmacher, W.; Hahn, E.G. Herbal medicine with curcuma and fumitory in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A. randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 40, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauche, R.; Kumar, S.; Hallmann, J.; Lüdtke, R.; Rampp, T.; Dobos, G.; Langhorst, J. Efficacy and safety of Ayurvedic herbs in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A randomised controlled crossover. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 26, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, L. Social factors and animal models of cannabis use. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2018, 140, 171–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Patient Information Marinol®. Available online: http://www.rxabbvie.com/pdf/marinol_PIL.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- Goyal, H.; Singla, U.; Gupta, U.; May, E. Role of cannabis in digestive disorders. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 29, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phatak, U.P.; Rojas-Velasquez, D.; Porto, A.; Pashankar, D.S. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use in young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aviram, J.; Samuelly-Leichtag, G. Efficacy of cannabis-based medicines for pain management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Phys. 2017, 20, e755–e796. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Melchior, C.; Bril, L.; Leroi, A.M.; Gourcerol, G.; Ducrotte, P. Are characteristics of abdominal pain helpful to identify patients with visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome? Results of a prospective study. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Verne, G.N. New insights into visceral hypersensitivity—clinical implications in IBS. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 8, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.C.; Ploner, M.; Wiech, K.; Bingel, U.; Wanigasekera, V.; Brooks, J.; Menon, D.K.; Tracey, I. Amygdala activity contributes to the dissociative effect of cannabis on pain perception. Pain 2013, 154, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klooker, T.K.; Leliefeld, K.E.; Van Den Wijngaard, R.M.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. The cannabinoid receptor agonist delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol does not affect visceral sensitivity to rectal distension in healthy volunteers and IBS patients. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.S.; Camilleri, M.; Busciglio, I.; Carlson, P.; Szarka, L.A.; Burton, D.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Pharmacogenetic trial of a cannabinoid agonist shows reduced fasting colonic motility in patients with nonconstipated irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1638–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, B.S.; Camilleri, M.; Eckert, D.; Carlson, P.; Ryks, M.; Burton, D.; Zinsmeister, A.R. Randomized pharmacodynamic and pharmacogenetic trial of dronabinol effects on colon transit in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2012, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, P.K.; Giri, D.D.; Singh, R.; Pandey, P.; Gupta, S.; Shrivastava, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Pandey, K.D. Therapeutic and medicinal uses of aloe vera: A review. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2013, 4, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.; Philpott, S.; Kumar, D.; Mendall, M. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of Aloe vera for irritable bowel syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2006, 60, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchings, H.A.; Wareham, K.; Baxter, J.N.; Atherton, P.; Kingham, J.G.C.; Duane, P.; Thomas, L.; Thomas, M.; Ch’ng, C.L.; Williams, J.G. A randomised, cross-over, placebo-controlled study of aloe vera in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: Effects on patient quality of life. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2011, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storsrud, S.; Ponten, I.; Simren, M. A pilot study of the effect of aloe barbadensis mill. extract (AVH200(R)) in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. JGLD 2015, 24, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khedmat, H.; Karbasi, A.; Amini, M.; Aghaei, A.; Taheri, S. Aloe vera in treatment of refractory irritable bowel syndrome: Trial on Iranian patients. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panahi, Y.; Khedmat, H.; Valizadegan, G.; Mohtashami, R.; Sahebkar, A. Efficacy and safety of Aloe vera syrup for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A pilot randomized positive-controlled trial. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2015, 35, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, C.; Sasaki, I.; Naito, H.; Ueno, T.; Matsuno, S. The herbal medicine Dai-Kenchu-Tou stimulates upper gut motility through cholinergic and 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 receptors in conscious dogs. Surgery 1999, 126, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg, M.A.; Palsson, O.S.; Ringel, Y.; Whitehead, W.E. Is ginger effective for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome? A double blind randomized controlled pilot trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuki, M.; Komazawa, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kusunoki, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Nakashima, S.; Uno, G.; Ikuma, I.; Shizuku, T.; Kinoshita, Y. Effects of Daikenchuto on abdominal bloating accompanied by chronic constipation: A prospective, single-center randomized open trial. Curr. Ther. Res. Clin. Exp. 2015, 77, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.-L.; Rayner, C.K.; Wu, K.-L.; Chuah, S.-K.; Tai, W.-C.; Chou, Y.-P.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Chiu, W.-K.; Hu, T.-H. Effect of ginger on gastric motility and symptoms of functional dyspepsia. World. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, M.; Miceli, E.; Mazzocchi, S.; Tana, P.; Corazza, G.R. The role of gastric accommodation in the pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2005, 9, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lazzini, S.; Polinelli, W.; Riva, A.; Morazzoni, P.; Bombardelli, E. The effect of ginger (Zingiber officinalis) and artichoke (Cynara cardunculus) extract supplementation on gastric motility: A pilot randomized study in healthy volunteers. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adams, D.; Dagenais, S.; Clifford, T.; Baydala, L.; King, W.J.; Hervas-Malo, M.; Moher, D.; Vohra, S. Complementary and alternative medicine use by pediatric specialty outpatients. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rösch, W.; Liebregts, T.; Gundermann, K.J.; Vinson, B.; Holtmann, G. Phytotherapy for functional dyspepsia: A review of the clinical evidence for the herbal preparation STW 5. Phytomedicine 2006, 13, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.N.; Kim, D.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, B.H.; Sohn, K.M.; Choi, M.J.; Choi, Y.H. Aloe-induced Toxic Hepatitis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 492–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | N | Age (Years) | Primary Outcome | Dose | Type of Study | Length of Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kline et al. [12] | 42 | 8–17 | Severity of pain | Capsule: 187 mg of peppermint oil 30–45 kg: 1 capsule TID >45 kg: 2 capsules TID | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial | 2 weeks | 75% reduction in severity of pain (p < 0.001) |

| Asgarshirazi et al. [13] | 88 | 4–13 | Duration, frequency, and severity of pain | Capsule: 187 mg of peppermint oil <45 kg: 1 capsule TID >45 kg: 2 capsules TID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 1 month | Duration, frequency, and severity of pain was significantly reduced (p = 0.0001) (p = 0.0001) (p = 0.001) |

| Cappello et al. [14] | 57 | 18–80 | Reduction of IBS symptoms | 225 mg of peppermint oil. 2 capsules BID | Randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 4 weeks | 75% of the patients in the peppermint oil group had reduced IBS symptoms (p < 0.009) |

| Merat et al. [15] | 60 | 36 ± 12 | Absence of abdominal pain or discomfort at week 8 | 0.2 mL peppermint oil TID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 8 weeks | 14 participants became pain free by week 8, vs. 6 in the control group (p < 0.001) |

| Alam et al. [16] | 65 | Age unknown | Abdominal symptoms Changes of quality of life | Peppermint oil TID | Randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 6 weeks | Abdominal pain was improved by peppermint oil use (p > 0.001) Quality of life did not improve significantly |

| Cash et al. [17] | 72 | 18–60 | Change in symptoms score | 180 mg Peppermint oil TID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 4 weeks | Greater reduction of symptoms in the peppermint group (p = 0.0246) |

| Author | N | Age (Years) | Primary Outcome | Dose | Type of Study | Length of Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madisch et al. [24] | 208 | 43.6 ± 12.9 | Changes in total abdominal pain scores Changes in irritable bowel syndrome symptom scores | 20 drops TID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 4 weeks | STW 5 reduced pain and IBS symptoms Pain: (p = 0.0009) IBS symptoms (p = 0.001) |

| von Arnim et al. [25] | 308 | 18–80 | Change in Gastrointestinal Symptom Score (GIS) | 20 drops TID | Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 8 weeks | GIS improved during STW 5 treatment (p < 0.05) |

| Braden et al. [26] | 103 | 18–85 | Change in Gastrointestinal Symptom Score (GIS) | 20 drops TID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial | 28 days | GIS improved more in the STW 5 group (p = 0.08) |

| Raedsch et al. [27] | 272 | 5–92 | Time to onset of symptom improvement after STW 5 dose | 20 drops TID | Noninterventional (observational) trial | 3 weeks | Patients experienced an improvement within 15–30 min after each STW 5 dose |

| Author | N | Age (Years) | Primary Outcome | Dose | Type of Study | Length of Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bundy et al. [36] | 207 | “Majority were over 50 years old” | IBS prevalence Abdominal pain/discomfort scores | 72 mg (1 tablet) or 144 mg (2 tablets) daily | Randomized, partially blinded, two-dose, pilot trial | 8 weeks | IBS prevalence decreased in both groups (p < 0.001) Abdominal pain/discomfort (p < 0.071) |

| Brinkhaus, et al. [37] | 106 | Mean age 48 +/−12 | Changes in ratings of IBS-related pain and distension | Curcuma Xanthorriza: 20 mg (1 tablet) TID Fumaria officinalis: 250 mg (2 tablets) TID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 18 weeks | IBS-related pain increased in the curcuma group (p = 0.81) IBS-related distension decreased in the curcuma group (p = 0.48) |

| Lauche, et al. [38] | 32 | 50.3 ± 11.9 | IBS symptom intensity | 5 g BID | Randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial | 4 weeks | No differences in IBS symptom intensity (p = 0.26) |

| Author | N | Age (Years) | Primary Outcome | Dose | Type of Study | Length of Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Klooker, et al. [47] | 22 | 20–52 | Sensory threshold | 5 or 10 mg daily | Randomized double-blind, crossover trial | 2 days | Dronabinol did not significantly affect sensory threshold for discomfort (No p value listed) |

| Wong, et al. [48] | 75 | 18–67 | Sensation during fasting and after a meal | 2.5 or 5 mg BID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial | 1 day | Dronabinol did not impact Sensation Gas (p = 0.39) Pain (p = 0.43) |

| Author | N | Age (Years) | Primary Outcome | Dose | Type of Study | Length of Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis et al. [51] | 58 | 18–65 | Change in global summated symptom score | 50 Ml QID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 3 months | No overall benefit for aloe vera versus placebo (p = 0.08) |

| Hutchings et al. [52] | 110 | 47.0 (SD 13.7) | Patient quality of life | 60 mL BID | Randomized, double-blind, cross-over, placebo controlled trial | 5 months | Aloe vera not shown to be superior to placebo (p > 0.05) |

| Størsrud et al. [53] | 68 | 18–65 | Subjects with reduction of ≥50 points on the IBS-SSS questionnaire | 250 mg BID | Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial | 4 weeks | Reduced symptom severity in the aloe vera group (p = 0.003) |

| Author | N | Age (Years) | Primary Outcome | Dose | Type of Study | Length of Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van Tilburg et al. [57] | 45 | ≥18 | 25% reduction in IBS-SS post-treatment | 1 g or 2 g ginger daily | Randomized, double-blind, controlled trial | 28 days | Ginger did not perform better than placebo: (p > 0.05) (57.1% responded to placebo) (46.7% responded to one gram of ginger) (33.3% responded to two grams of ginger) |

| Yuki et al. [58] | 10 | 34–85 | Safety and efficacy of DKT for abdominal bloating | 15 g TID | Randomized, prospective trial | 14 days | VAS score was reduced from 76 to 30: (p = 0.005) |

| Hu et al. [59] | 11 | Not listed | Gastric half-emptying time Abdominal symptoms | 1.2 g ginger root powder | Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial | 2 days | Gastric emptying was more rapid after ginger than placebo (p ≤ 0.05) No significant changes in nausea/abdominal discomfort from baseline (No p value listed) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fifi, A.C.; Axelrod, C.H.; Chakraborty, P.; Saps, M. Herbs and Spices in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review of Clinical Trials. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111715

Fifi AC, Axelrod CH, Chakraborty P, Saps M. Herbs and Spices in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review of Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2018; 10(11):1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111715

Chicago/Turabian StyleFifi, Amanda C., Cara Hannah Axelrod, Partha Chakraborty, and Miguel Saps. 2018. "Herbs and Spices in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review of Clinical Trials" Nutrients 10, no. 11: 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111715

APA StyleFifi, A. C., Axelrod, C. H., Chakraborty, P., & Saps, M. (2018). Herbs and Spices in the Treatment of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: A Review of Clinical Trials. Nutrients, 10(11), 1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111715