Quantifying Agricultural Flooding Practices for Migratory Bird Populations: A Test Case of Incentivized Habitat Management in the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta (USA) Using In Situ Sensors, Digital Elevation Models, and PlanetScope Imagery

Highlights

- Using remotely sensed imagery, we developed the Field Inundation Tool/Survey.

- Inundation metrics derived from the Field Inundation Tool/Survey were comparable to those determined from in situ water sensors and digital elevation models.

- The Field Inundation Tool/Survey allows for quantification of spatial and temporal patterns of flooding in the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta; a similar approach could be applied elsewhere.

- The Field Inundation Tool/Survey provides a relatively straightforward assessment of flooding without on-the-ground measures.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Flooding Treatments

2.2. Overview of the FITS Model

2.3. Imagery Selection for the FITS

2.4. Imagery Processing and Conceptual Representations for the FITS

2.5. Use of In Situ Sensors and a DEM for Aquatic Habitat Estimates for the FITS

3. Results

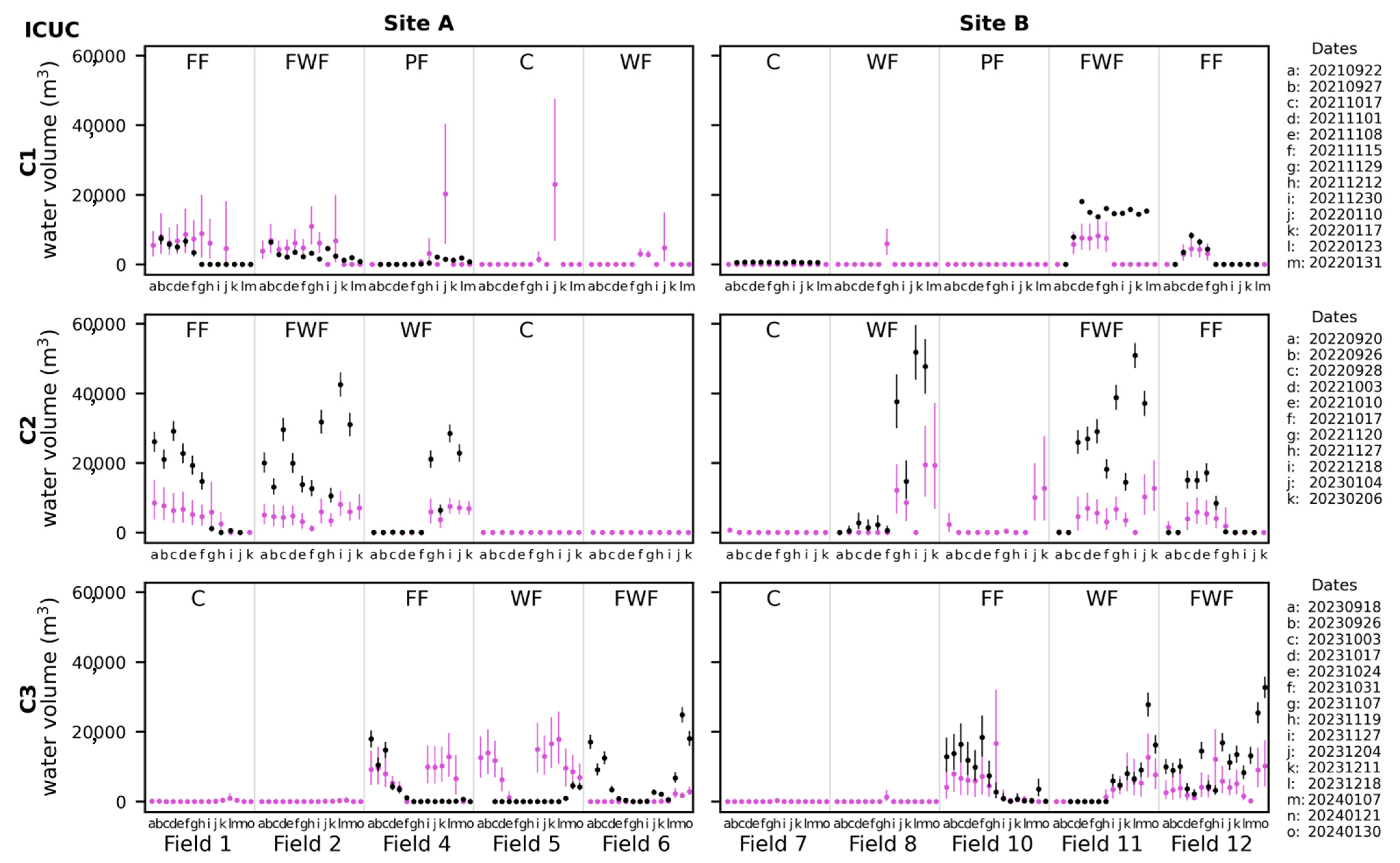

3.1. Aquatic Habitat Detection Characteristics During C1 (Via PlanetScope Imagery)

3.2. Aquatic Habitat Estimates During C1 via the In Situ Sensors and the DEM

3.3. Aquatic Habitat Detection Characteristics During C2 (Via PlanetScope Imagery)

3.4. Aquatic Habitat Estimates During C2 via the In Situ Sensors and the DEM

3.5. Aquatic Habitat Detection Characteristics During C3 (Via PlanetScope Imagery)

3.6. Aquatic Habitat Detection Characteristics During C3 (Via the In Situ Sensors and the DEM)

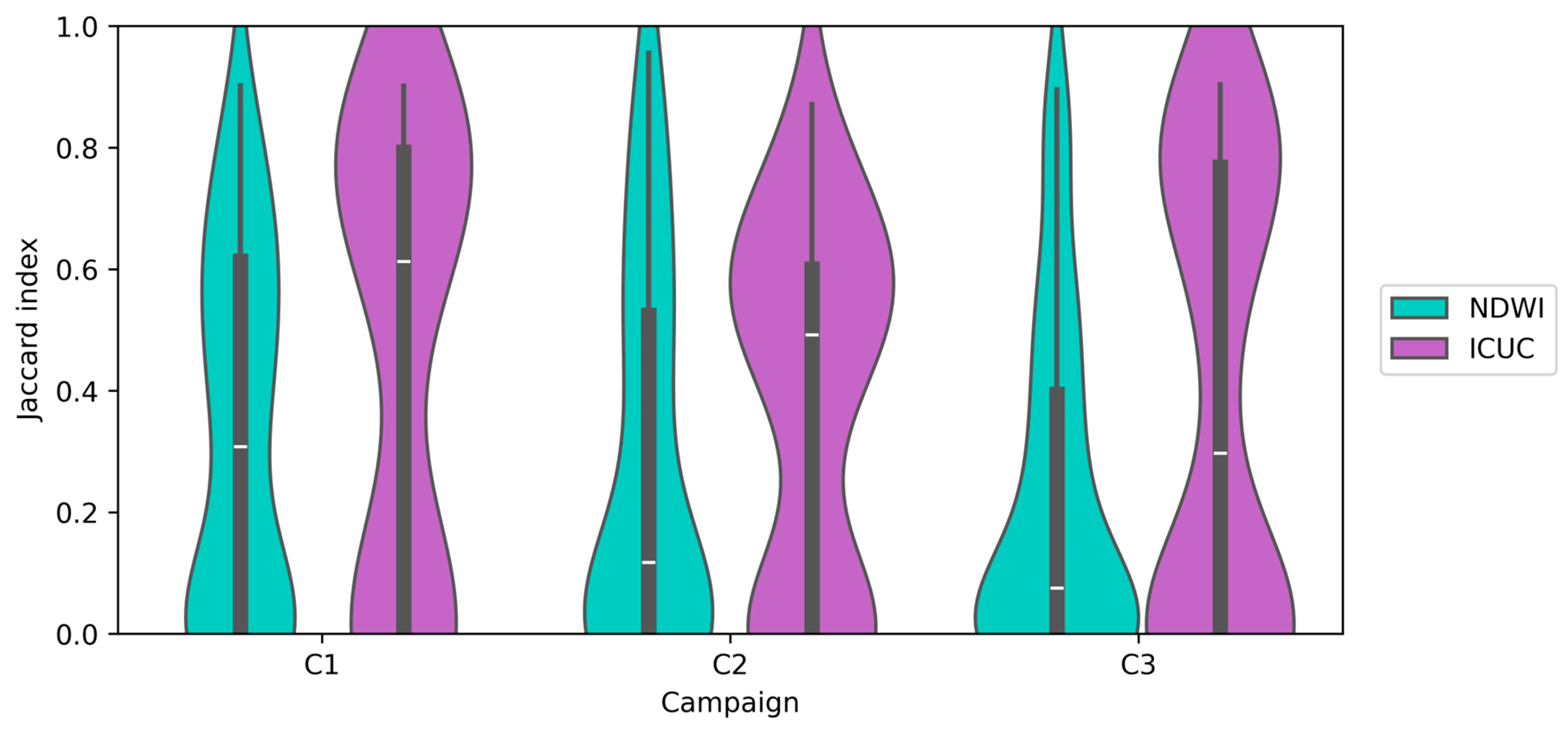

3.7. Relationships Among Methods and Accuracy

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Trends for the FITS

4.2. Agroecological and Avian Conservation Applications

4.3. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3DEP | Three-dimensional Elevation Program |

| AOI | Area of Interest |

| ArcGIS | Aeronautical Reconnaissance Coverage Geographic Information System |

| ARS | Agricultural Research Service |

| C | Control |

| C1 | Campaign 1 |

| C2 | Campaign 2 |

| C3 | Campaign 3 |

| CA | California |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| ESRI | Environmental Systems Research Institute |

| FITS | Field Inundation Tool/Survey |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| lidar | Light Detection and Ranging |

| m | Meter |

| MAP | Mississippi Alluvial Plain |

| MS | Mississippi |

| N | Nitrogen |

| N2 | Dinitrogen |

| NH4+ | Ammonium |

| NO3- | Nitrate |

| NDWI | Normalized Difference Water Index |

| NRCS | Natural Resources Conservation Service |

| ICUC | Iso Cluster Unsupervised Classification |

| PF | Passive Flooding |

| FF | Fall Flooding |

| WF | Winter Flooding |

| FWF | Fall and Winter Flooding |

| PS2 | PlanetScope Two-Dimensional Imagery |

| PS2.SD | PlanetScope Two-Dimensional Imagery and Super Dove Satellite Sensor |

| PSB.SD | PlanetScope Imagery captured from Super Dove Satellite Sensor |

| RGBNIR | Red–Green–Blue Near-Infrared |

| RTK | Real-time Kinematic |

| TX | Texas |

| USA | United States of America |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| YMD | Yazoo–Mississippi Delta |

References

- Myers, J.P.; McClain, P.D.; Morrison, R.I.; Antas, P.Z.; Canevari, P.; Harrington, B.A.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Pulido, V.; Sallaberry, M.; Senner, S.E. Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network. Wader Study Group Bull. 1987, 49, 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Loesch, C.R.; Twedt, D.J.; Tripp, K.; Hunter, W.C.; Woodrey, M.S. Development of Management Objectives for Waterfowl and Shorebirds in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. In Proceedings of the USDA Forest Service RMRS-P-16, Cape May, NJ, USA, 1–5 October 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Omernik, J.; Griffith, G. Ecoregions of the conterminous United States: Evolution of a hierarchical spatial framework. Environ. Manag. 2014, 54, 1249–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.; Scarpignato, A.L.; Huysman, A.; Hostetler, J.A.; Cohen, E.B. Migratory connectivity of North American waterfowl across administrative flyways. Ecol. Appl. 2023, 33, e2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, C.; Murray, E.; Foti, T.; Pagan, J.; Williamson, M.; Langston, H. An ecosystem restoration model for the Mississippi Alluvial Valley based on geomorphology, soils, and hydrology. Wetlands 2009, 29, 430–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twedt, D.J.; Nelms, C.O.; Rettig, V.E.; Aycock, S.R. Shorebird use of managed wetlands in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. Am. Midl. Nat. 1998, 140, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasarer, L.M.W.; Taylor, J.M.; Rigby, J.R.; Locke, M.A. Trends in land use, irrigation, and streamflow alteration in the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, M.A.; Witthaus, L.M.; Lizotte, R.E.; Heintzman, L.J.; Moore, M.T.; O’Reilly, A.; Wells, R.R.; Langendoen, E.J.; Bingner, R.L.; Gohlson, D.M.; et al. The LTAR cropland common experiment in the Lower Mississippi River Basin. J. Environ. Qual. 2024, 53, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, S.; Barrow, W.; Keeland, B.; Walls, S.; Telesco, D. Effects of conservation practices on wetland ecosystem services in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. Ecol. Appl. 2011, 21, S31–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Geological Survey (USGS). National Water Summary on Wetland Resources; USGS Report Series 2425; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; 431p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsch, W.J.; Gosselink, J.G. Wetlands, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Twedt, D.J.; Nelms, C.O. Waterfowl density on agricultural fields managed to retain water in winter. Wild. Soc. Bull. 1999, 27, 924–930. [Google Scholar]

- Lehnen, S.E.; Krementz, D.G. Use of aquaculture ponds and other habitats by autumn migrating shorebirds along the Lower Mississippi River. Environ. Manag. 2013, 52, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golet, G.H.; Low, C.; Avery, S.; Andrews, K.; McColl, C.J.; Laney, R.; Reynolds, M.D. Using ricelands to provide temporary shorebird habitat during migration. Ecol. Appl. 2018, 28, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, K.M.; Webb, E.B.; Mengel, D.C.; Kearns, L.J.; McKellar, A.E.; Matteson, S.W.; Williams, B.R. Wetland management practices and secretive marsh bird habitat in the Mississippi Flyway: A review. J. Wild. Manag. 2023, 87, e22451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, S.W.; Kaminski, R.M.; Rodrigue, P.B.; Dewey, J.C.; Schoenholtz, S.H.; Gerard, P.D.; Reinecke, K.J. Soil and nutrient retention in winter-flooded ricefields with implications for watershed management. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2009, 64, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firth, A.G.; Baker, B.H.; Brooks, J.P.; Smith, R.; Iglay, R.B.; Davis, J.B. Low external input sustainable agriculture: Winter flooding in rice fields increases bird use, fecal matter and soil health, reducing fertilizer requirements. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 300, 106962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.B.; Webb, E.; Kaminski, R.M.; Barbour, P.J.; Vilella, F.J. Comprehensive framework for ecological assessment of migratory bird habitat initiative following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Southeast. Nat. 2014, 13, G66–G81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lausch, A.; Bannehr, L.; Berger, S.A.; Borg, E.; Bumberger, J.; Hacker, J.M.; Heege, T.; Hupfer, M.; Jung, A.; Kuhwald, K.; et al. Monitoring water diversity and water quality with remote sensing and traits. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S.K. The use of the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) in the delineation of open water features. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 17, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFeeters, S.K. Using the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) within a Geographic Information System to detect swimming pools for mosquito abatement: A practical approach. Remote Sens. 2013, 5, 3544–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.D.; Heintzman, L.J.; Starr, S.M.; Wright, C.K.; Henebry, G.M.; McIntyre, N.E. Hydrological dynamics of temporary wetlands in the southern Great Plains as a function of surrounding land use. J. Arid Environ. 2014, 109, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzman, L.J.; Starr, S.M.; Mulligan, K.R.; Barbato, L.S.; McIntyre, N.E. Using satellite imagery to examine the relationship between surface-water dynamics of the salt lakes of western Texas and Ogallala Aquifer depletion. Wetlands 2017, 37, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzman, L.J.; Auerbach, E.S.; Kilborn, D.H.; Starr, S.M.; Mulligan, K.R.; Barbato, L.S.; McIntyre, N.E. Identifying areas of wetland and wind turbine overlap in the south-central Great Plains of North America. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 1995–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, C.R.; Colwell, M.A.; Taft, O.W.; Safran, R.J. Interspecific differences in habitat use of shorebirds and waterfowl foraging in managed wetlands of California’s San Joaquin Valley. Waterbirds 2000, 23, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Tercero, M.C.; Álvarez-Rogel, J.; Conesa, H.M.; Ferrer, M.A.; Calderón, A.A.; López-Orenes, A.; González-Alcaraz, M.N. Response of biochemical processes of the water-soil-plant system to experimental flooding-drying conditions in a eutrophic wetland: The role of Phragmites australis. Plant Soil 2015, 396, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, G. Identification of novel denitrifying bacteria Stenotrophomonas sp. ZZ15 and Oceanimonas sp. YC13 and application for removal of nitrate from industrial wastewater. Biodegradation 2009, 20, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Taylor, J.M.; Read, Q.D.; Moore, M.T.; Locke, M.A.; Hoeksema, J.D. Water quality and soil nutrient availability trade-offs associated with timing and duration of managed flooding for migratory bird habitat. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2025, 89, e70077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counce, E.M. How Does the Creation of Temporary Wetland Habitation on Agricultural Fields in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley Affect the Abundance of Migratory Shorebirds? Master’s Thesis, The University of Mississippi, University, MS, USA, December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, C.; Curcó, A.; Riera, X.; Ripoll, I.; Sánchez, C. Influence on birds of rice field management practices during the growing season: A review and an experiment. Waterbirds 2010, 33, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuford, W.D.; Reiter, M.E.; Strum, K.M.; Gilbert, M.M.; Hickey, C.M.; Golet, G.H. The benefits of crops and field management practices to wintering waterbirds in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta of California. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2016, 31, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toral, G.M.; Aragonés, D.; Bustamante, J.; Figuerola, J. Using Landsat images to map habitat availability for waterbirds in rice fields. Ibis 2011, 153, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, M.E.; Elliott, N.K.; Jongsomjit, D.; Golet, G.H.; Reynolds, M.D. Impact of extreme drought and incentive programs on flooded agriculture and wetlands in California’s Central Valley. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sampling Dates: C1 | Imagery Dates: C1 | Sampling Dates: C2 | Imagery Dates: C2 | Sampling Dates: C3 | Imagery Dates: C3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 September 2021 | 22 September 2021 | 19 September 2022 | 20 September 2022 | 16 September 2023 | 16 September 2023 |

| 27 September 2021 | 27 September 2021 | 26 September 2022 | 26 September 2022 | 18 September 2023 | 18 September 2023 |

| 29 September 2021 | - | 28 September 2022 | 28 September 2022 | 25 September 2023 | 26 September 2023 |

| 4 October 2021 | - | 3 October 2022 | 3 October 2022 | 2 October 2023 | 3 October 2023 |

| 12 October 2021 | - | 11 October 2022 | 10 October 2022 | 10 October 2023 | - |

| 18 October 2021 | 17 October 2021 | 17 October 2022 | 17 October 2022 | 16 October 2023 | 17 October 2023 |

| 25 October 2021 | - | 24 October 2022 | - | 23 October 2023 | 24 October 2023 |

| 1 November 2021 | 1 November 2021 | 31 October 2022 | - | 30 October 2023 | 31 October 2023 |

| 8 November 2021 | 8 November 2021 | 7 November 2022 | - | 6 November 2023 | 7 November 2023 |

| 15 November 2021 | 15 November 2021 | 14 November 2022 | - | 13 November 2023 | - |

| 22 November 2021 | - | 19 November 2022 | - | 20 November 2023 | 19 November 2023 |

| 29 November 2021 | 29 November 2021 | 21 November 2022 | 20 November 2022 | 27 November 2023 | 27 November 2023 |

| 6 December 2021 | - | 28 November 2022 | 27 November 2022 | 4 December 2023 | 4 December 2023 |

| 13 December 2021 | 12 December 2021 | 5 December 2022 | - | 11 December 2023 | 11 December 2023 |

| 20 December 2021 | - | 12 December 2022 | - | 18 December 2023 | 18 December 2023 |

| 29 December 2021 | 30 December 2021 | 19 December 2022 | 18 December 2022 | 8 January 2024 | 7 January 2024 |

| 3 January 2022 | - | 3 January 2023 | 4 January 2023 | 15 January 2024 | - |

| 10 January 2022 | 10 January 2022 | 9 January 2023 | - | 22 January 2024 | 21 January 2024 |

| 18 January 2022 | 17 January 2022 | 17 January 2023 | - | 29 January 2024 | 30 January 2024 |

| 24 January 2022 | 23 January 2022 | 23 January 2023 | - | ||

| 31 January 2022 | 31 January 2022 | 30 January 2023 | - | ||

| 6 February 2023 | 6 February 2023 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Heintzman, L.J.; Langendoen, E.J.; Moore, M.T.; Barrett, D.E.; McIntyre, N.E.; Witthaus, L.M.; Lizotte, R.E., Jr.; Johnson, F.E., II; Locke, M.A.; Blocker, V.M.; et al. Quantifying Agricultural Flooding Practices for Migratory Bird Populations: A Test Case of Incentivized Habitat Management in the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta (USA) Using In Situ Sensors, Digital Elevation Models, and PlanetScope Imagery. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030477

Heintzman LJ, Langendoen EJ, Moore MT, Barrett DE, McIntyre NE, Witthaus LM, Lizotte RE Jr., Johnson FE II, Locke MA, Blocker VM, et al. Quantifying Agricultural Flooding Practices for Migratory Bird Populations: A Test Case of Incentivized Habitat Management in the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta (USA) Using In Situ Sensors, Digital Elevation Models, and PlanetScope Imagery. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030477

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeintzman, Lucas J., Eddy J. Langendoen, Matthew T. Moore, Damien E. Barrett, Nancy E. McIntyre, Lindsey M. Witthaus, Richard E. Lizotte, Jr., Frank E. Johnson, II, Martin A. Locke, Victoria M. Blocker, and et al. 2026. "Quantifying Agricultural Flooding Practices for Migratory Bird Populations: A Test Case of Incentivized Habitat Management in the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta (USA) Using In Situ Sensors, Digital Elevation Models, and PlanetScope Imagery" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030477

APA StyleHeintzman, L. J., Langendoen, E. J., Moore, M. T., Barrett, D. E., McIntyre, N. E., Witthaus, L. M., Lizotte, R. E., Jr., Johnson, F. E., II, Locke, M. A., Blocker, V. M., Ursic, M. E., Nelson, A. M., Taylor, J. M., & Hoeksema, J. D. (2026). Quantifying Agricultural Flooding Practices for Migratory Bird Populations: A Test Case of Incentivized Habitat Management in the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta (USA) Using In Situ Sensors, Digital Elevation Models, and PlanetScope Imagery. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030477