Small Ship Detection Based on a Learning Model That Incorporates Spatial Attention Mechanism as a Loss Function in SU-ESRGAN

Highlights

- Integrating ESRGAN and its semantic-structure-enhanced variant (SU-ESRGAN) into SAR imagery processing improved visual quality and detail reconstruction, though ESRGAN tended to amplify SAR-specific noise.

- The spatial-attention-augmented SA/SU-ESRGAN further refined ship boundaries and suppressed noise, yielding marginally higher detection accuracy, particularly for low-resolution and small ship scenarios.

- Incorporating semantic structure and spatial attention in super-resolution networks enhances SAR image interpretability and robustness for downstream tasks like ship detection.

- Tailoring super-resolution models to domain-specific noise and texture characteristics can substantially improve small object detection performance in remote sensing applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Foundational ESRGAN Research

2.2. ESRGAN Applications in Remote Sensing

2.3. SAR Ship Detection

2.4. Spatial Attention Mechanisms

2.5. Semantic and Structural Loss Functions

3. Proposed Method

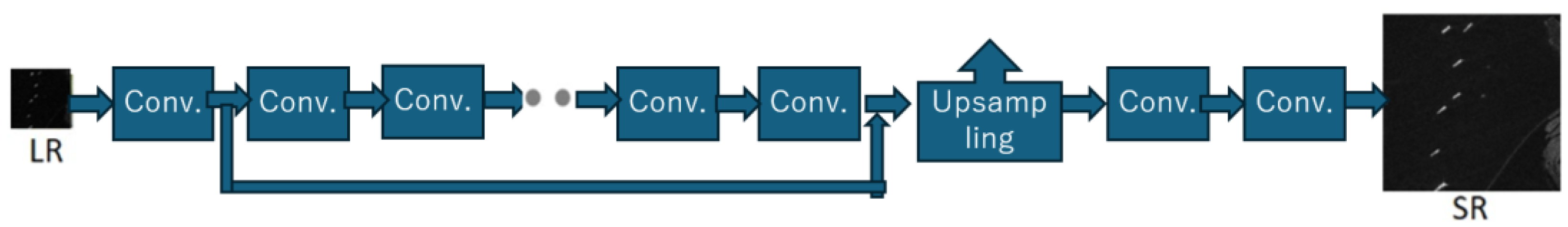

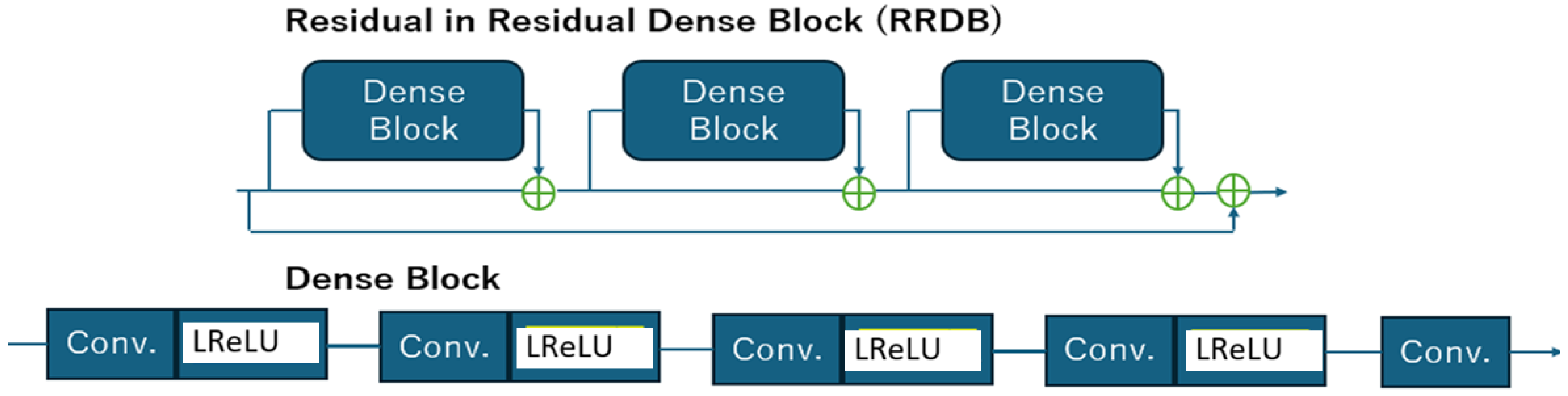

3.1. ESRGAN Foundation

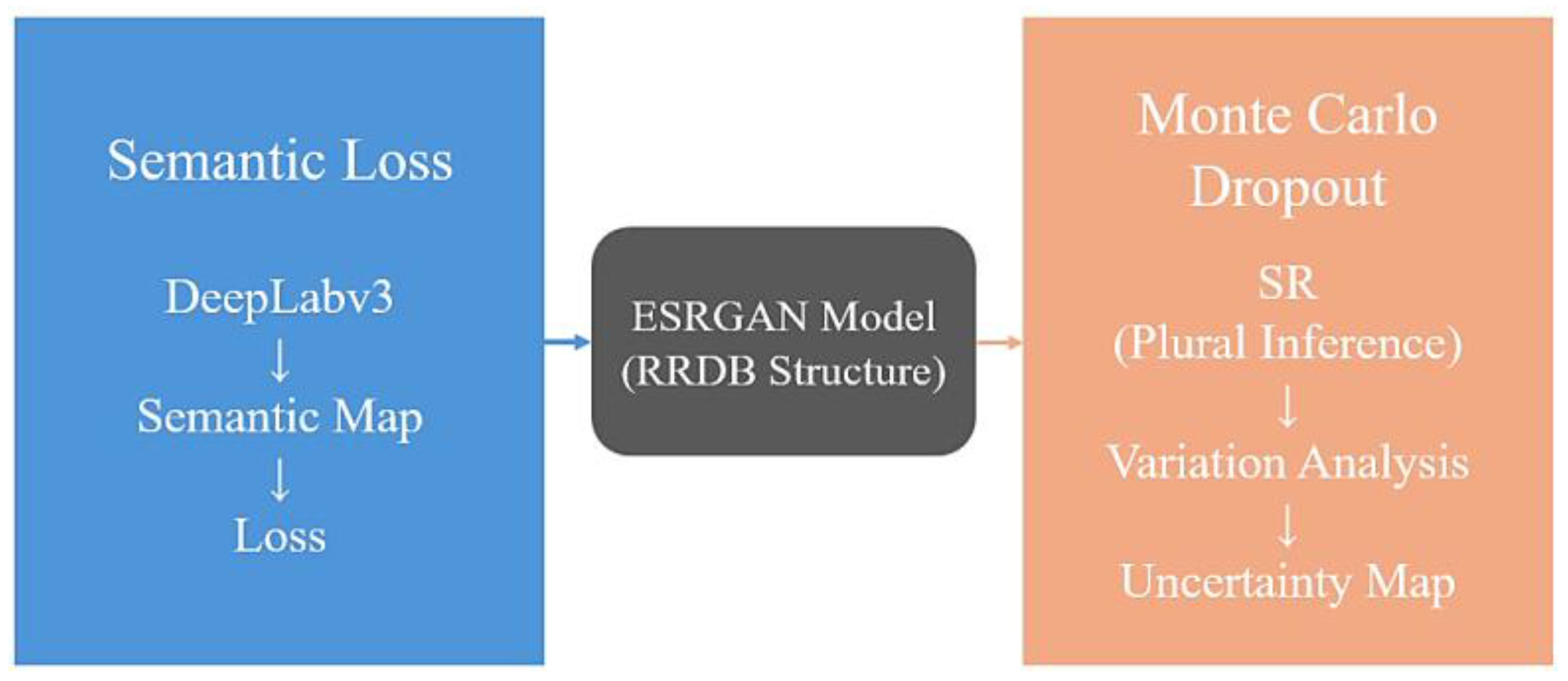

3.2. SU-ESRGAN: Semantic-Aware Enhancement

3.3. SA/SU-ESRGAN: Spatial Attention Integration

- attn_map = sigmoid(conv(pooling(features))) # From generator feats

- attn_loss = F.mse_loss(attn_map * sr, attn_map * hr)

- This boosts reproducibility; full repo forthcoming post-acceptance.

3.4. Discriminator of SA/SU-ESRGAN

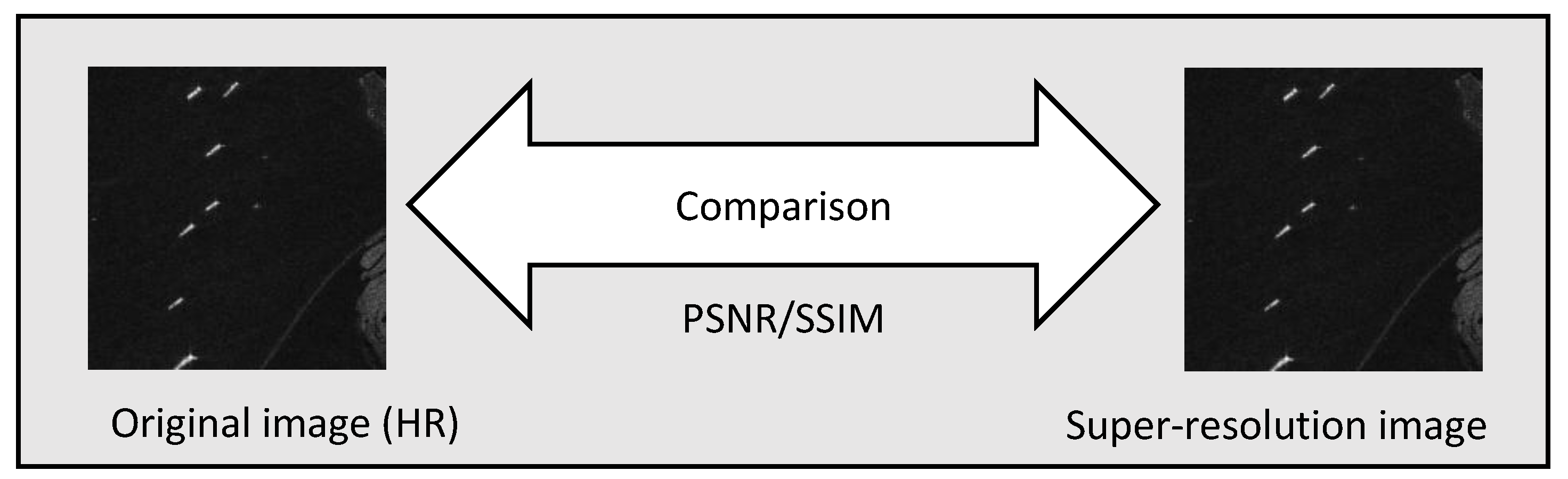

3.5. Super-Resolution Performance Evaluation

3.6. Comparison of the Proposed Method to the Other Recent New Architectures

4. Experiment

4.1. Data Used

- Each ship in the dataset is annotated with both rotatable bounding boxes (RBox) and horizontal bounding boxes (BBox) for precise localization.

- The dataset provides both 8-bit pseudo-color and 16-bit complex SAR data.

- It supports ship detection research using deep learning; baseline results have been established using popular detectors like R3Det (https://github.com/SJTU-Thinklab-Det/r3det-pytorch, accessed on 20 November 2025) and YOLOv4 (https://github.com/Tianxiaomo/pytorch-YOLOv4, accessed on 20 November 2025).

- An advanced weakly supervised anomaly detection method (MemAE (https://github.com/donggong1/memae-anomaly-detection, accessed on 20 November 2025)) was proposed to reduce false alarms with less annotation effort.

- The dataset emphasizes small target detection, as small vessels constitute around 98% of targets, posing a significant challenge due to fewer distinguishing features.

4.2. Example Images of Super-Resolution and Ship Detection by ESRGAN

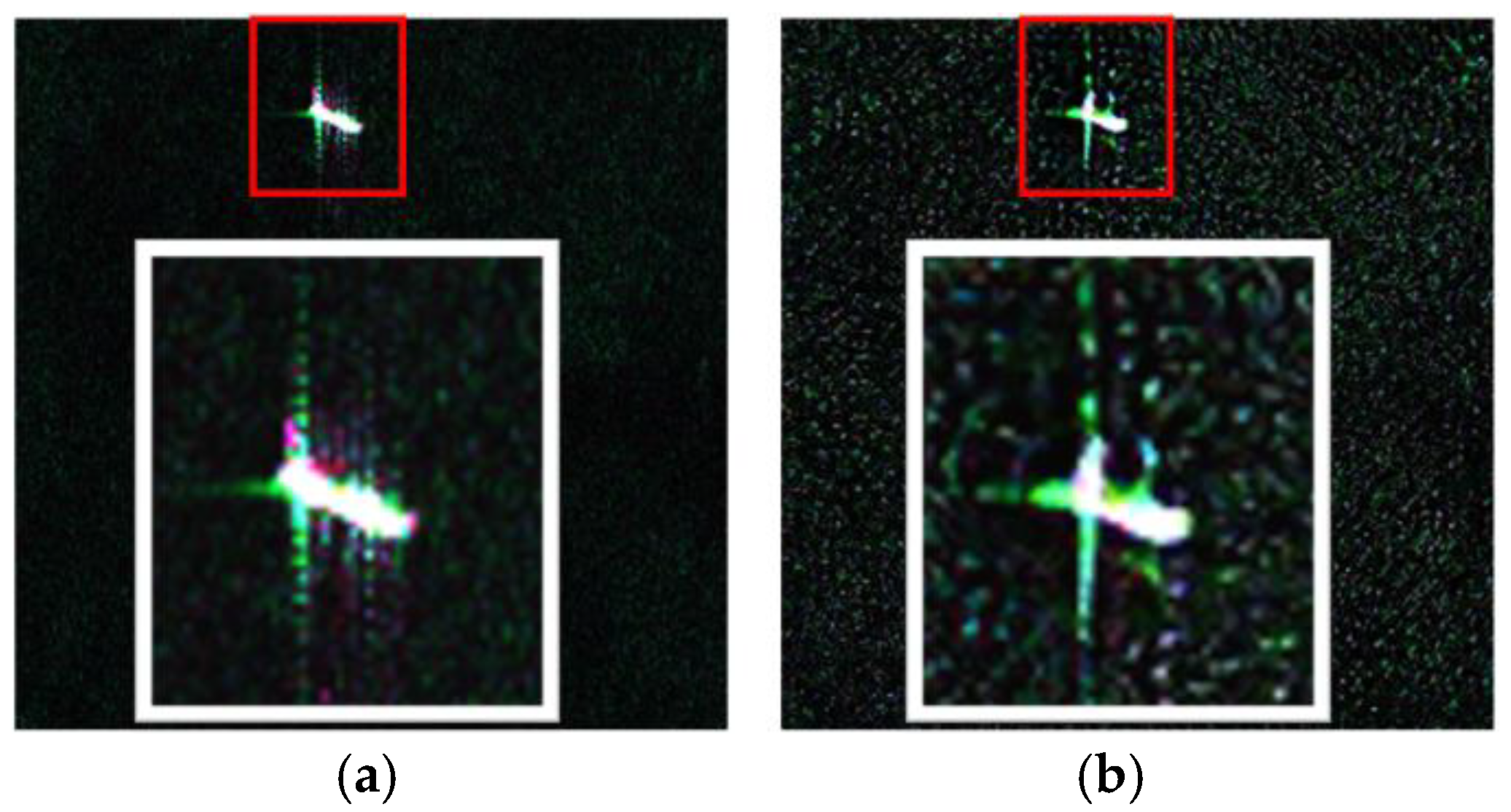

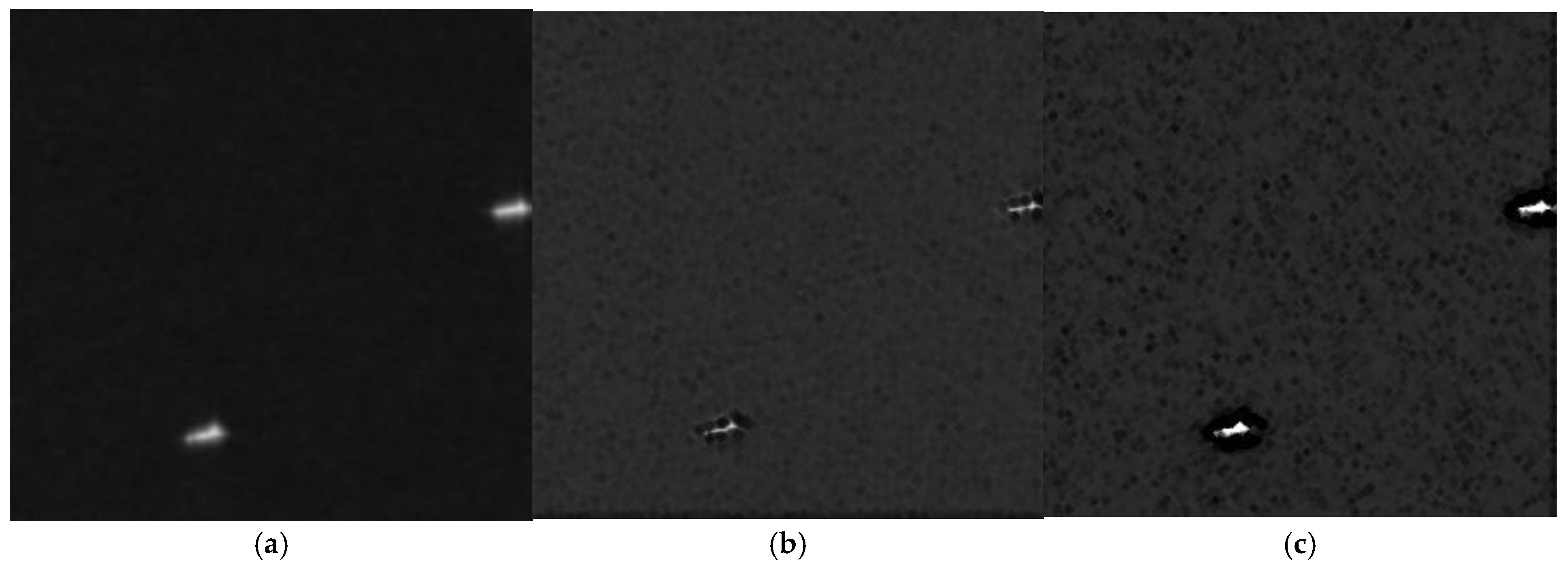

4.3. Frequency Component Comparison Among Original, Super-Resolution by Bicubic, ESRGAN, and SU-ESRGAN

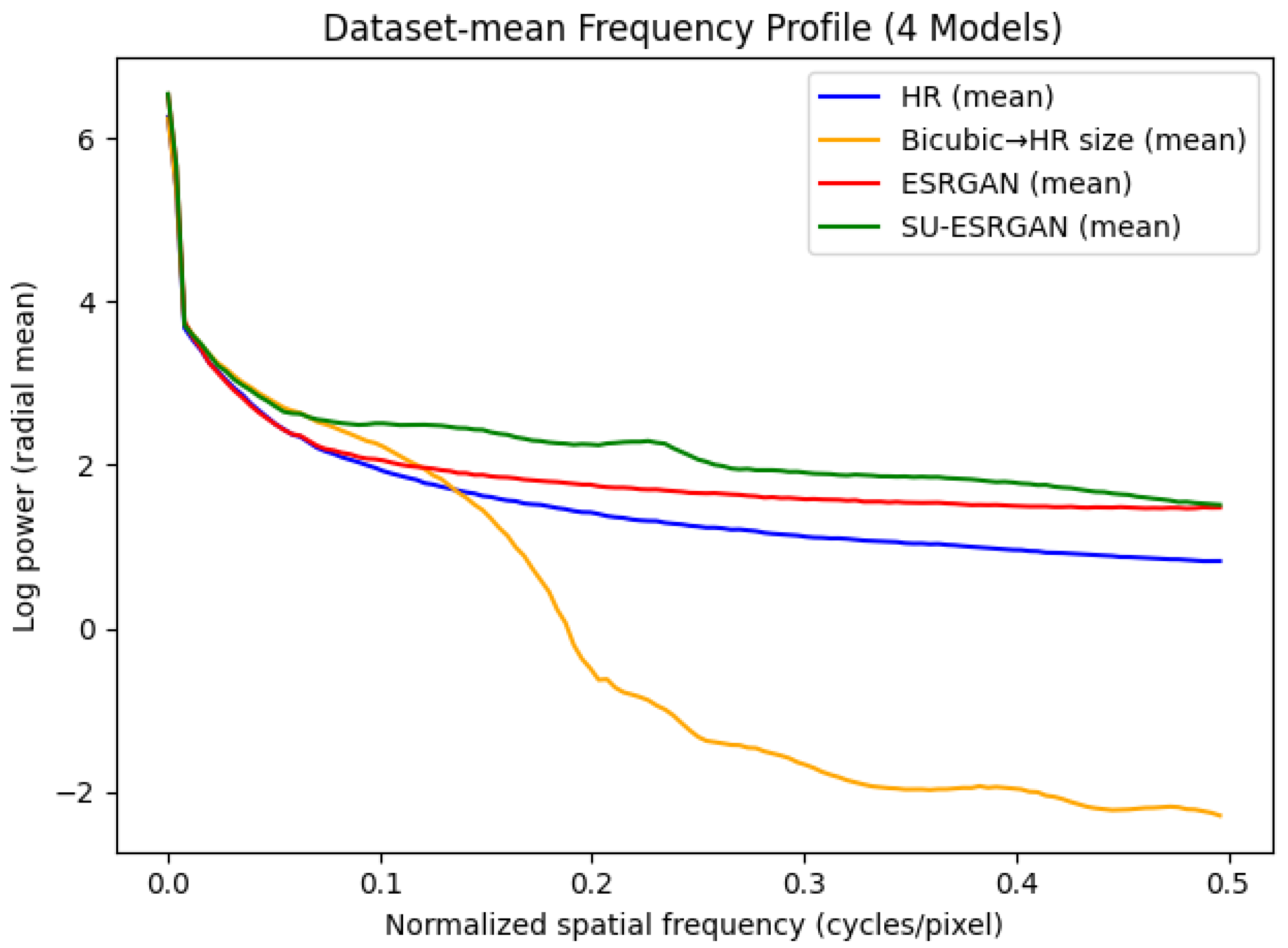

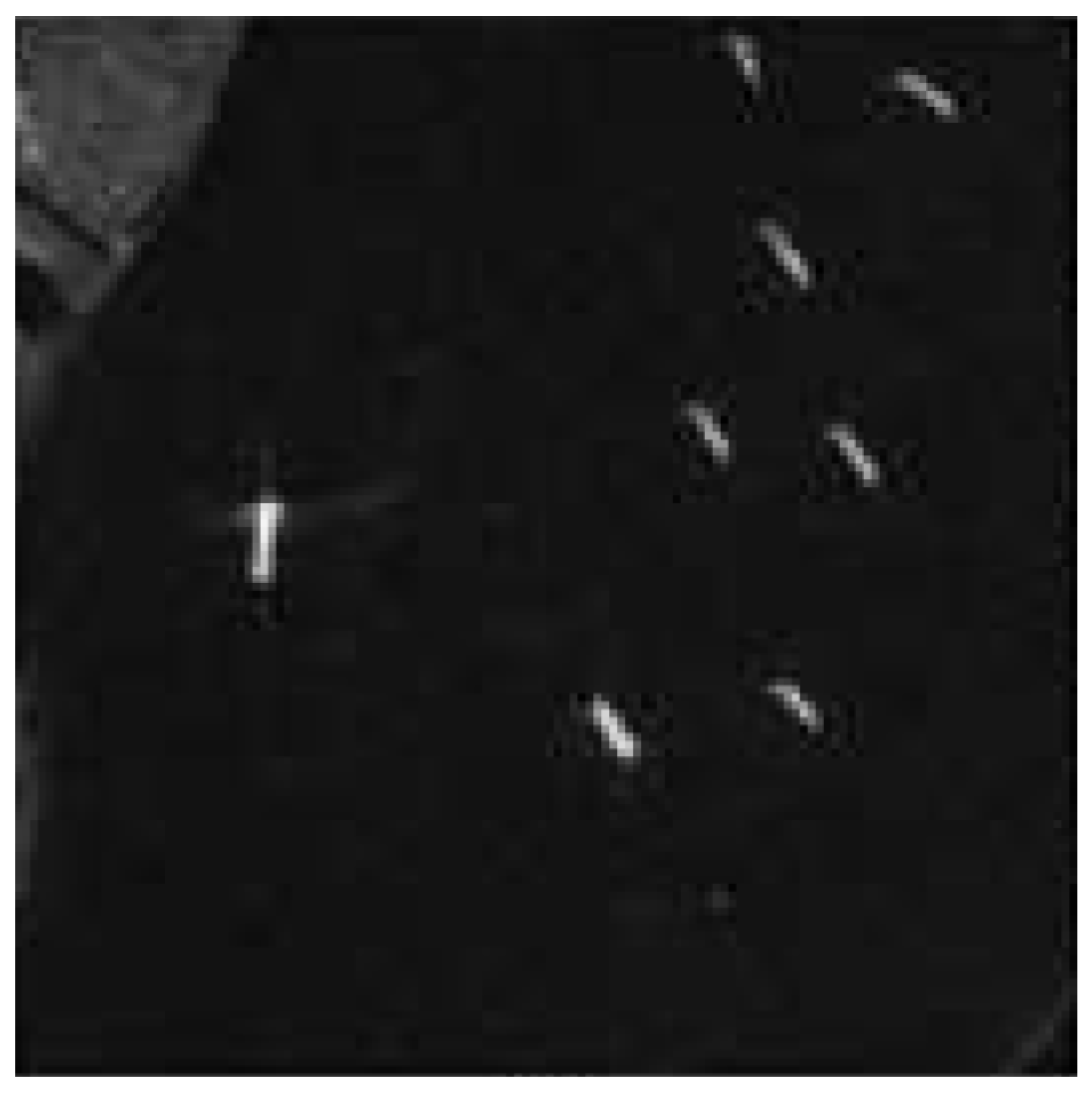

4.4. Example Images Derived from SU-ESRGAN

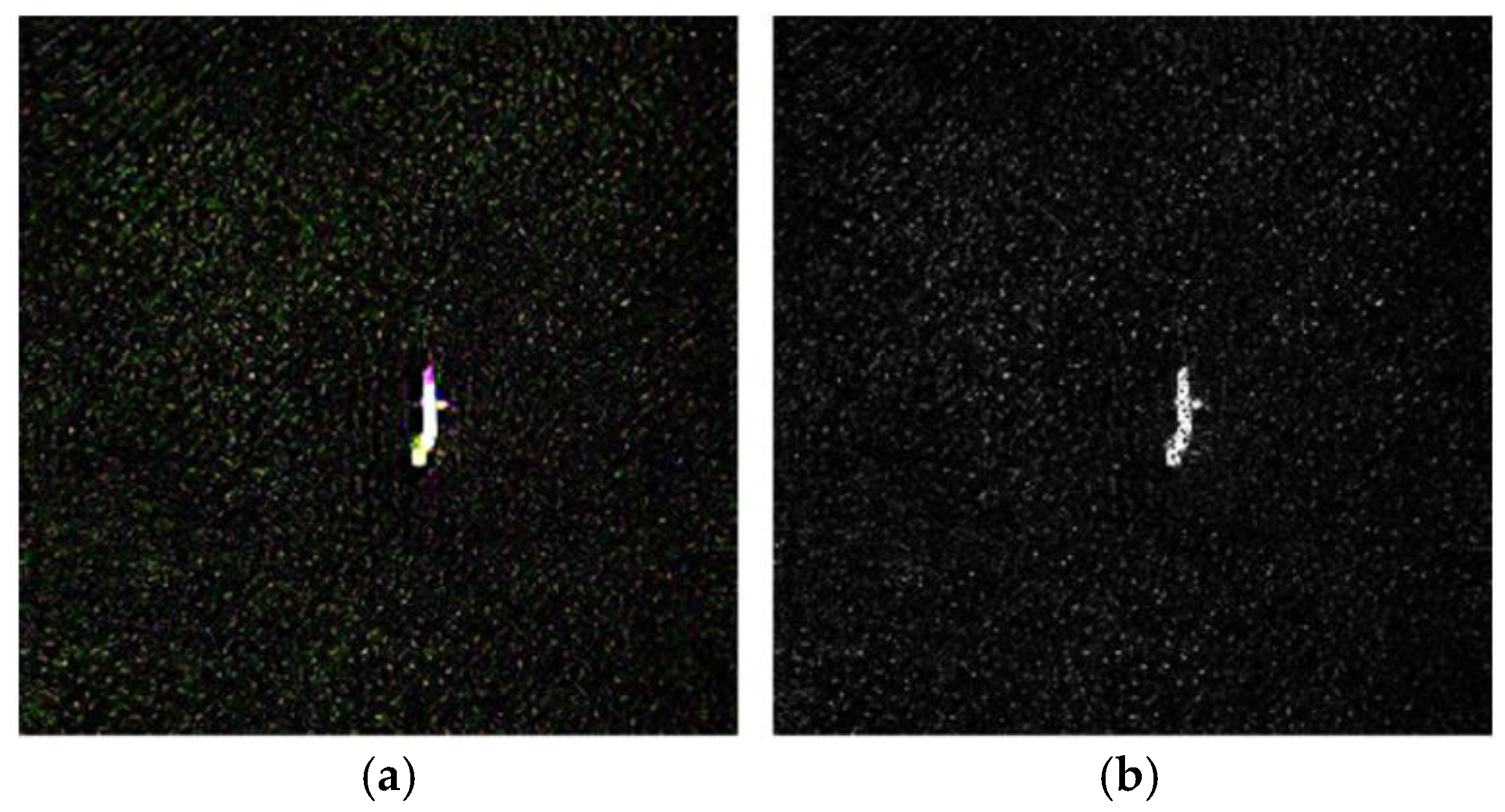

4.5. Comparison of PSNR and SSIM Between SU-ESRGAN and SA/SU-ESRGAN

- Paired t-test comparing PSNR/SSIM between methods (p < 0.05 threshold);

- McNemar’s test for detection rate comparisons;

- After that, the following stratified performance analysis is made:

- Separate results by ship size categories (small/medium/large);

- Performance vs. sea state conditions;

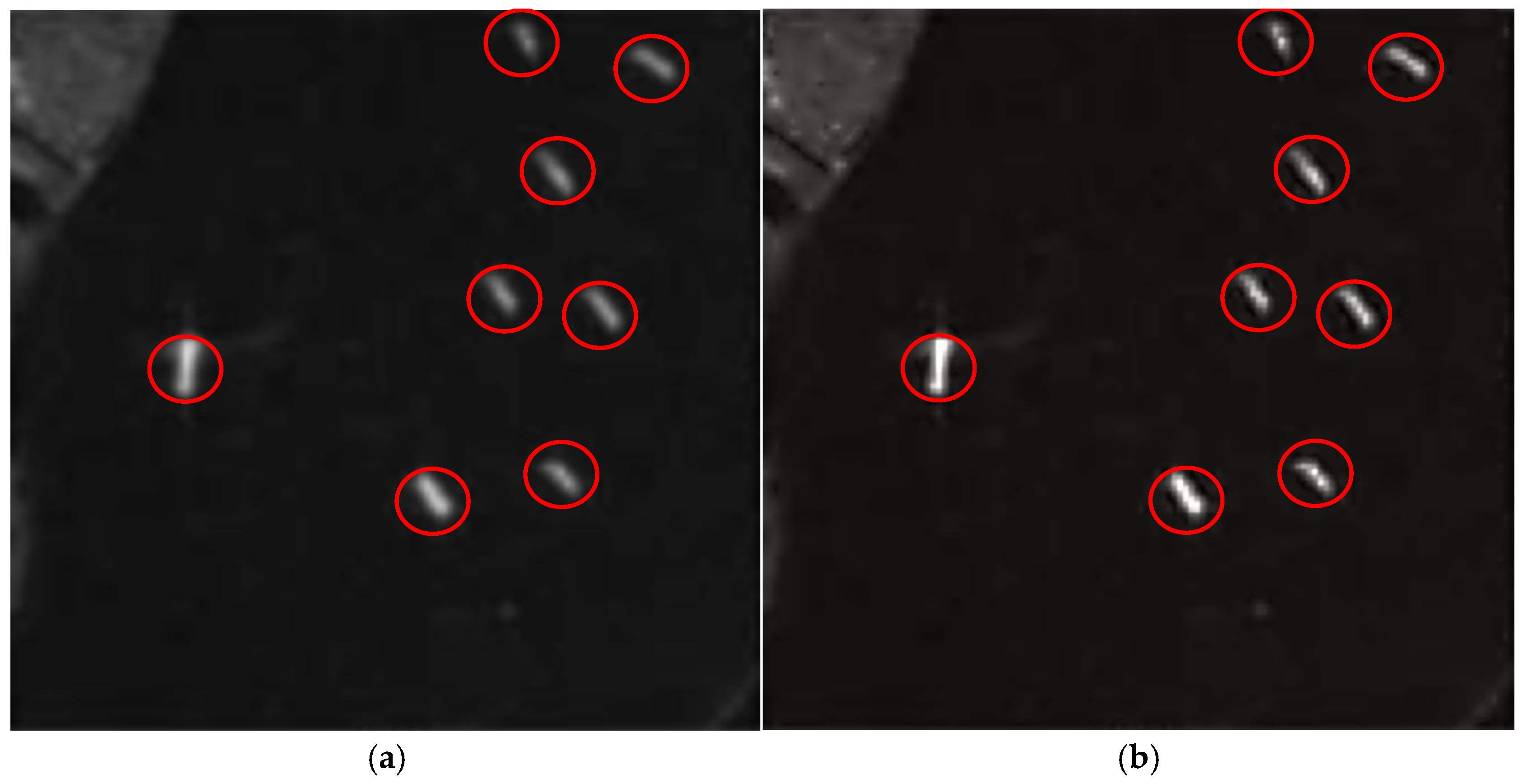

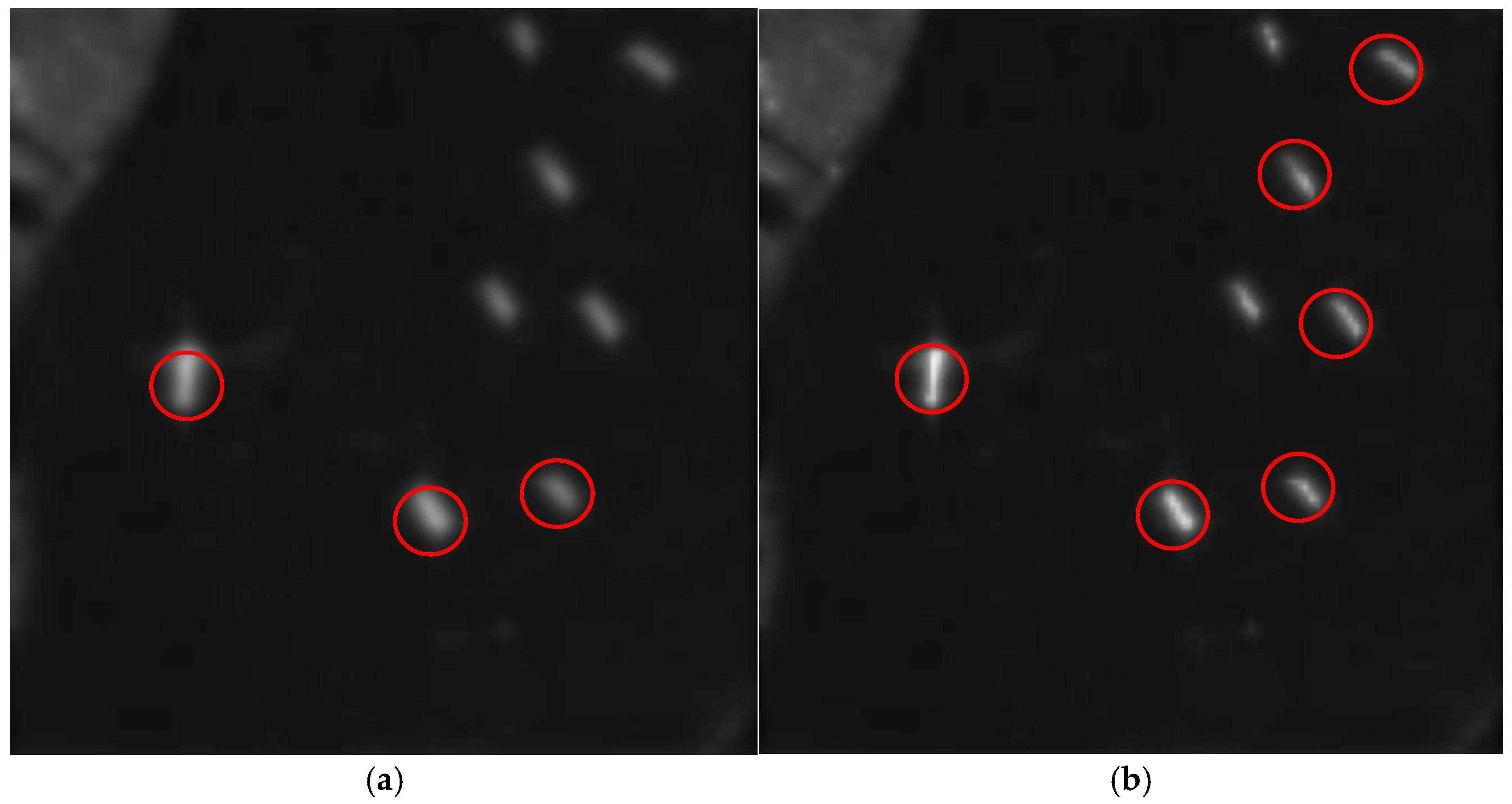

4.6. Resultant Image Comparison Between SU-ESRGAN and SA/SU-ESRGAN

4.7. Ship Detection Performance Evaluation for SU-ESRGAN and SA/SU-ESRGAN

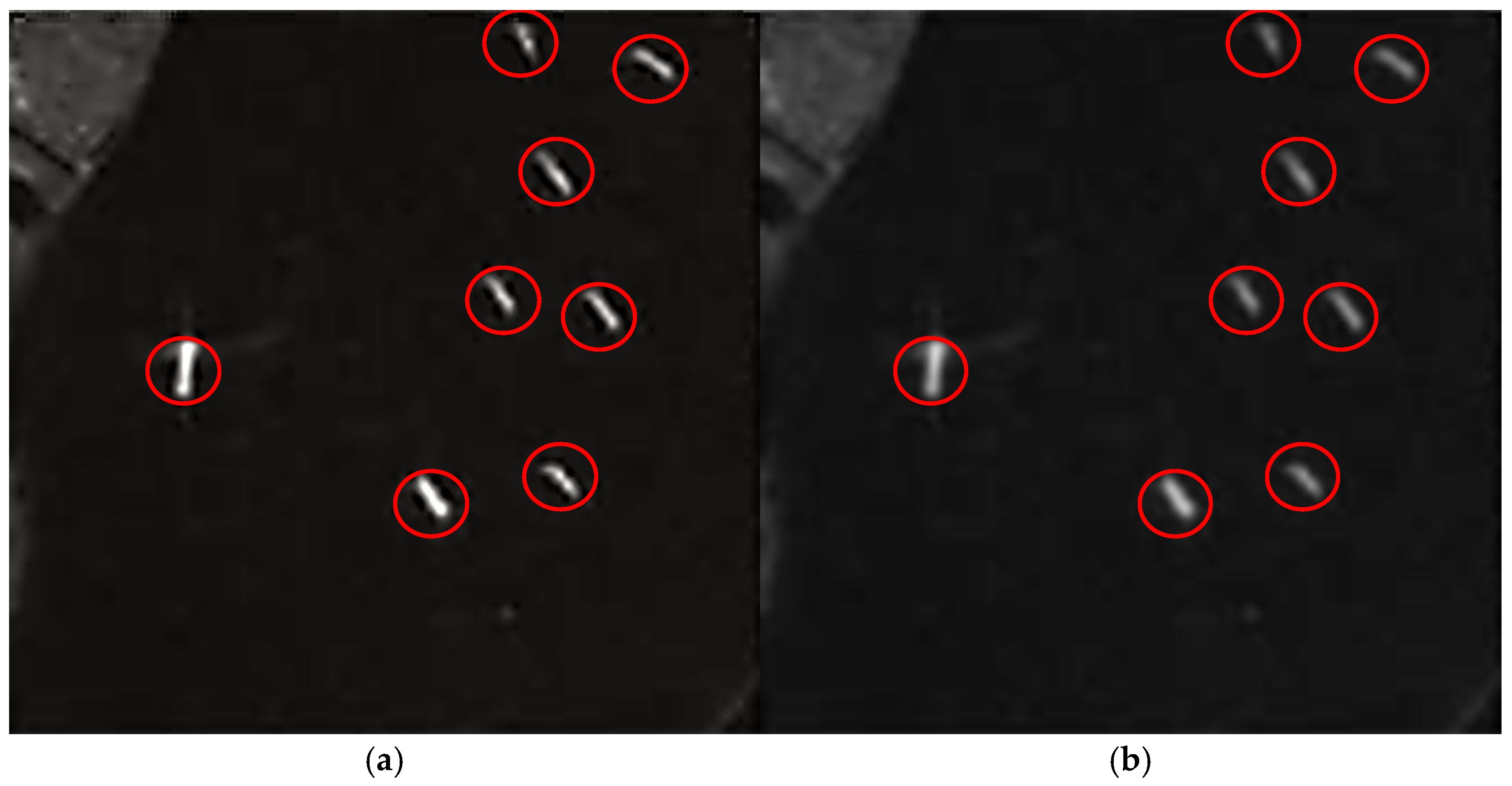

4.8. Effect of SA/SU-ESRGAN for a Small Ship Detection

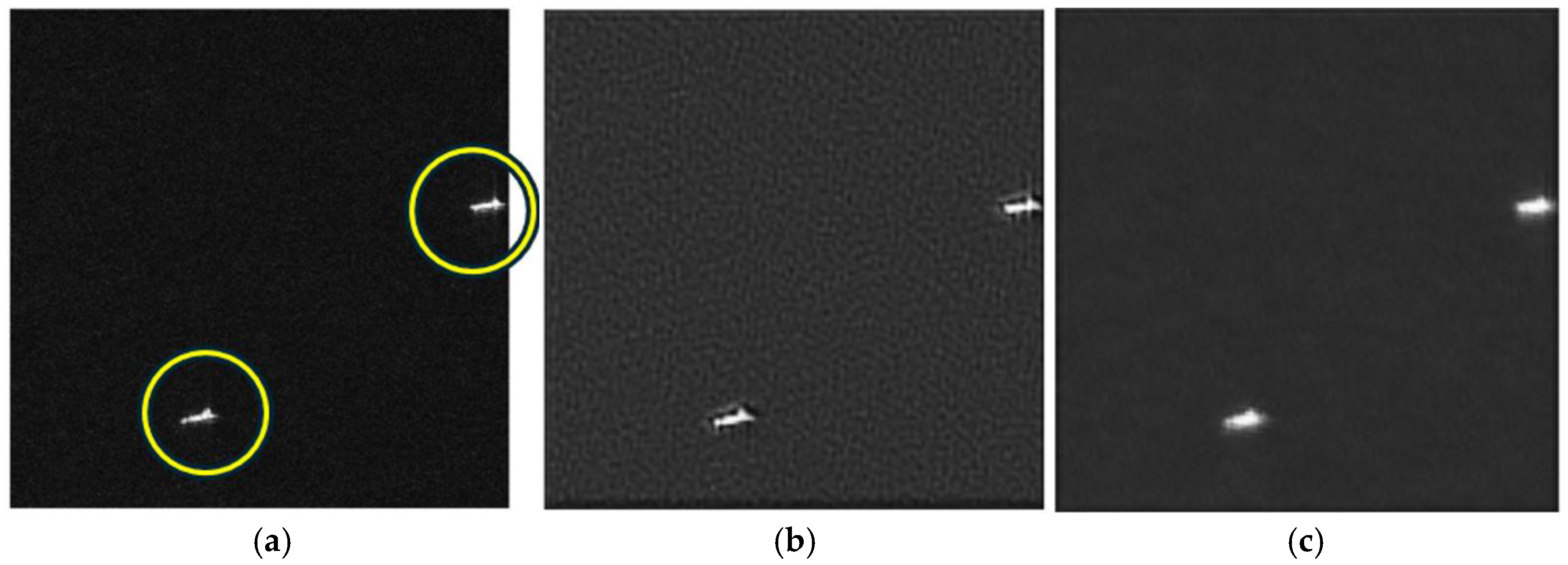

- Spatial resolution: 0.5 m, 1 m, and 3 m;

- Range resolution: 1 m to 5 m;

- Image size: 800 × 800 pixels (after cropping).

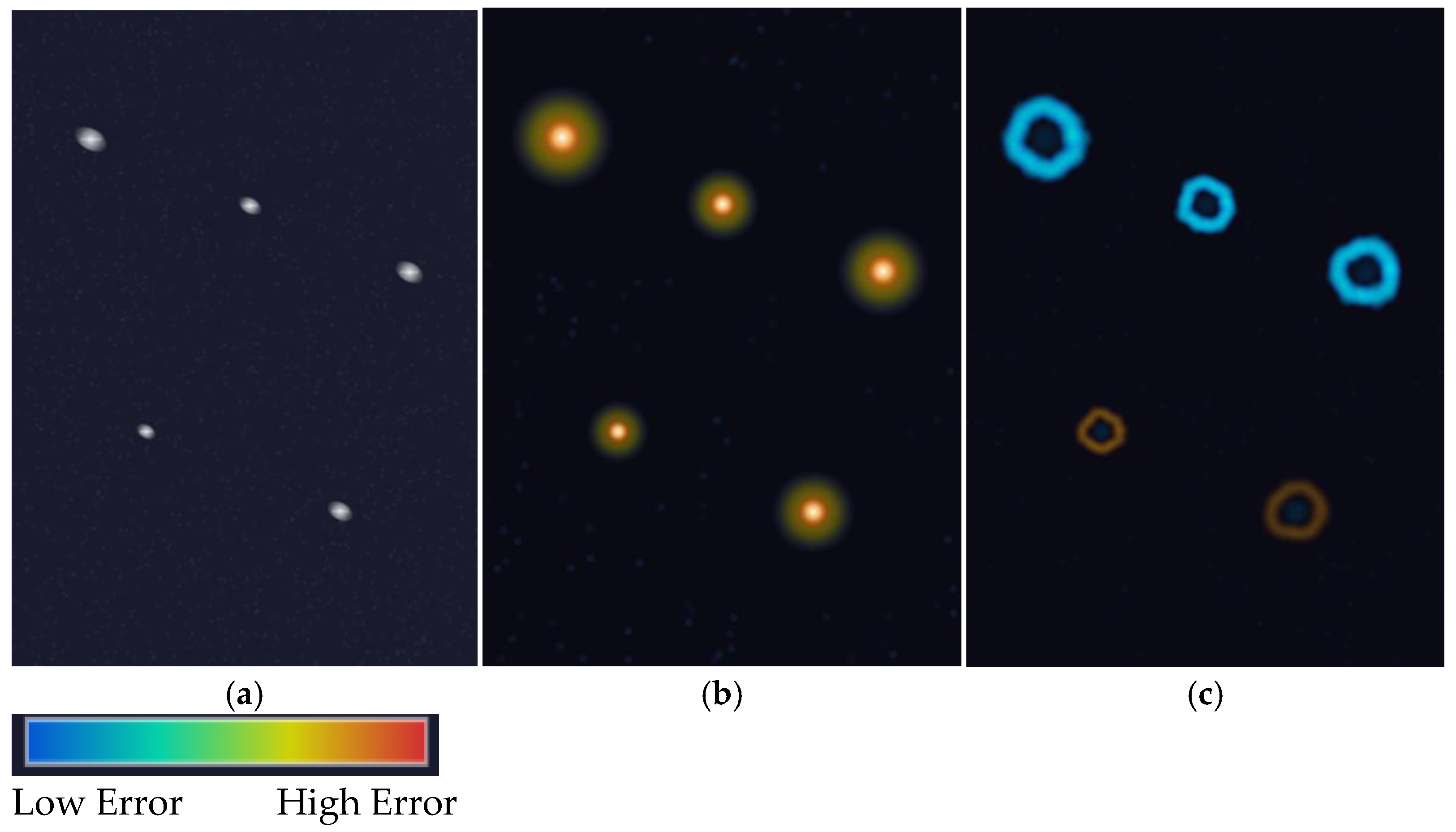

4.9. Effect of Spatial Attention and Difference Heat Map Analysis

4.10. Comparative Study Among Attention-Based Super Resolution Variants

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Novel Spatial Attention Innovation

- (2)

- Transformative Detection Gains

- (3)

- Broad Generalization Potential

6. Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yasir, M.; Jianhua, W.; Mingming, X.; Hui, S.; Zhe, Z.; Shanwei, L.; Colak, A.T.I.; Hossain, S. Ship detection based on deep learning using SAR imagery: A systematic literature review. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Wei, S. A SAR Dataset of Ship Detection for Deep Learning under Complex Backgrounds. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Ke, X.; Zhan, X.; Shi, J.; Wei, S.; Pan, D.; Li, J.; Su, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. LS-SSDD-v1.0: A Deep Learning Dataset Dedicated to Small Ship Detection from Large-Scale Sentinel-1 SAR Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, K.; Wu, S.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Qiao, Y.; Loy, C.C. ESRGAN: Enhanced Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Computer Vision, ECCV 2018, Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Xie, L.; Dong, C.; Shan, Y. Real-ESRGAN: Training Real-World Blind Super-Resolution with Pure Synthetic Data. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops (ICCVW), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 1905–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar, P. SU-ESRGAN: Semantic and Uncertainty-Aware ESRGAN for Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.00750. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.00750 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Aldoğan, C.F.; Aksu, K.; Demirel, H. Enhancement of Sentinel-2A Images for Ship Detection via Real-ESRGAN Model. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowska, K.; Wierzbicki, D. Modified ESRGAN with Uformer for Video Satellite Imagery Super-Resolution. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, C.; Su, H.; Gao, L.; Wang, T. Deep Learning for SAR Ship Detection: Past, Present and Future. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xue, Q. RLE-YOLO: A Lightweight and Multiscale SAR Ship Detection Method Based on YOLO. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 3201–3213. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Gong, D.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Wong, K.-Y.K. Learning Spatial Attention for Face Super-Resolution. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2021, 30, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, N. An Advanced Features Extraction Module for Remote Sensing Image Super-Resolution. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.04595. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.04595 (accessed on 20 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.H.; Xu, T.X.; Liu, J.J.; Liu, Z.N.; Jiang, P.T.; Mu, T.J.; Zhang, S.H.; Martin, R.R.; Cheng, M.M.; Hu, S.M. Attention Mechanisms in Computer Vision: A Survey. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 331–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K.; Nakaoka, Y.; Okumura, H. Method for Landslide Area Detection Based on EfficientNetV2 with Optical Image Converted from SAR Image Using pix2pixHD with Spatial Attention Mechanism in Loss Function. Information 2024, 15, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K. Modified pix2pixHD for Enhancing Spatial Resolution of Image for Conversion from SAR Images to Optical Images in Application of Landslide Area Detection. Information 2025, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K.; Nakaoka, Y.; Okumura, H. Method for Landslide Area Detection with RVI Data Which Indicates Base Soil Areas Changed from Vegetated Areas. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, F.; Jin, Y.; Ma, X.; Cen, Y.; Hu, S.; Li, Y. SemDNet: Semantic-guided despeckling network for SAR images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 296, 129200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zou, B.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Cross-Resolution SAR Target Detection Using Structural Hierarchy Adaptation and Reliable Adjacency Alignment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Cai, X.; Li, Z.; Xing, J.; Ai, J. Where is my attention? An explainable AI exploration in water detection from SAR imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 130, 103878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awais, C.M.; Reggiannini, M.; Moroni, D.; Salerno, E. A Survey on SAR Ship Classification Using Deep Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.11906. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.11906 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Pan, Z. A dual-polarimetric SAR ship detection dataset and a memory-augmented autoencoder-based detection method. Sensors 2021, 21, 8478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Li, K.; Wang, L.; Zhong, B.; Fu, Y. Image Super-Resolution Using Very Deep Residual Channel Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 294–310. Available online: https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_ECCV_2018/papers/Yulun_Zhang_Image_Super-Resolution_Using_ECCV_2018_paper.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Dai, T.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, S.T.; Zhang, L. Second-order Attention Network for Single Image Super-Resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 11065–11074. [Google Scholar]

| Metrics | Description | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| PSNR | Peak signal-to-noise ratio | Much larger than 30 dB would be fine. |

| SSIM | Similarity of image structure | The closer to 1 the better. |

| Metric | SU-ESRGAN | SA/SU-ESRGAN | p-Value | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSNR (dB) | 26.24 ± 1.35 | 26.20 ± 1.28 | 0.64 | 0.03 (negligible) |

| SSIM | 0.503 ± 0.082 | 0.449 ± 0.079 | <0.01 * | 0.67 (medium) |

| Ship-region PSNR | 24.8 ± 1.8 | 25.3 ± 1.6 | 0.03 * | 0.29 (small) |

| Detection Recall | 0.73 ± 0.15 | 0.82 ± 0.12 | <0.001 ** | 0.67 (medium) |

| Method | Type | PSNR | SSIM | Detection Recall | Params (M) | Inference Time (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCAN | Channel Attn | 26.3 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 15.4 | 195 |

| SemDNet | SAR-specific | 26.1 | 0.5 | 0.71 | 8.3 | 160 |

| SU-ESRGAN | GAN + Semantic | 26.2 | 0.5 | 0.73 | 17.2 | 190 |

| SA/SU-ESRGAN | Proposed | 26.2 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 17.8 | 195 |

| Model | mAP@0.5 | Recall (Small) | Precision | Detection (Ships/8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline LR | 0.65 | 0.38 | 0.72 | 3/8 |

| SU-ESRGAN | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.78 | 4/8 |

| SA/SU-ESRGAN | 0.78 | 0.62 | 0.82 | 6/8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arai, K.; Morita, Y.; Okumura, H. Small Ship Detection Based on a Learning Model That Incorporates Spatial Attention Mechanism as a Loss Function in SU-ESRGAN. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030417

Arai K, Morita Y, Okumura H. Small Ship Detection Based on a Learning Model That Incorporates Spatial Attention Mechanism as a Loss Function in SU-ESRGAN. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030417

Chicago/Turabian StyleArai, Kohei, Yu Morita, and Hiroshi Okumura. 2026. "Small Ship Detection Based on a Learning Model That Incorporates Spatial Attention Mechanism as a Loss Function in SU-ESRGAN" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030417

APA StyleArai, K., Morita, Y., & Okumura, H. (2026). Small Ship Detection Based on a Learning Model That Incorporates Spatial Attention Mechanism as a Loss Function in SU-ESRGAN. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030417