Dynamic Monitoring and Analysis of Mountain Excavation and Land Creation Projects in Lanzhou Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Machine Learning

Highlights

- This study establishes an integrated multi-source remote sensing framework to monitor Mountain Excavation and Land Creation Projects (MELCPs) in Lanzhou. Fusing ascending and descending Sentinel-1 SAR data significantly enhances excavation area detection accuracy to 87.1%. Optimized Random Forest classification achieves 91.2% accuracy in mapping reclaimed land. InSAR revealed that construction-induced deep consolidation caused subsidence up to 333.8 mm, offering key insights for engineering safety in mountainous cities.

- Dual-orbit fusion improves detection accuracy.

- Two-layer mechanism explains subsidence causes.

- Establishes a monitoring and assessment system for mountainous city expansion.

- Offers evidence-based guidance for optimizing ecological restoration policies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

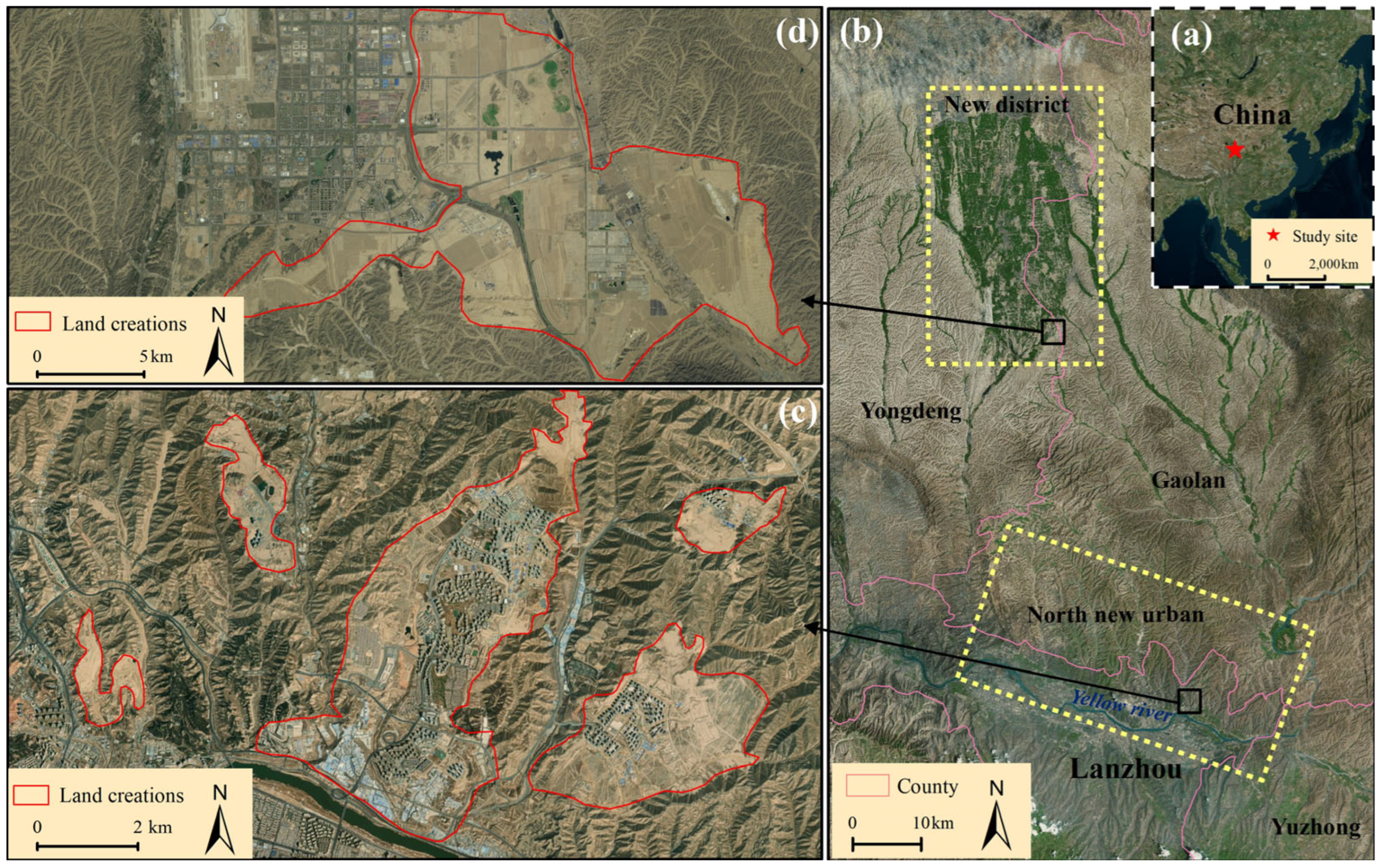

2.1. A Brief Description of the Study Area

2.2. Data

- (1)

- Sentinel data and pre-processing

- (2)

- Sample data for land cover classification in MELCPs

- (3)

- Digital Elevation Model and terrain derivatives

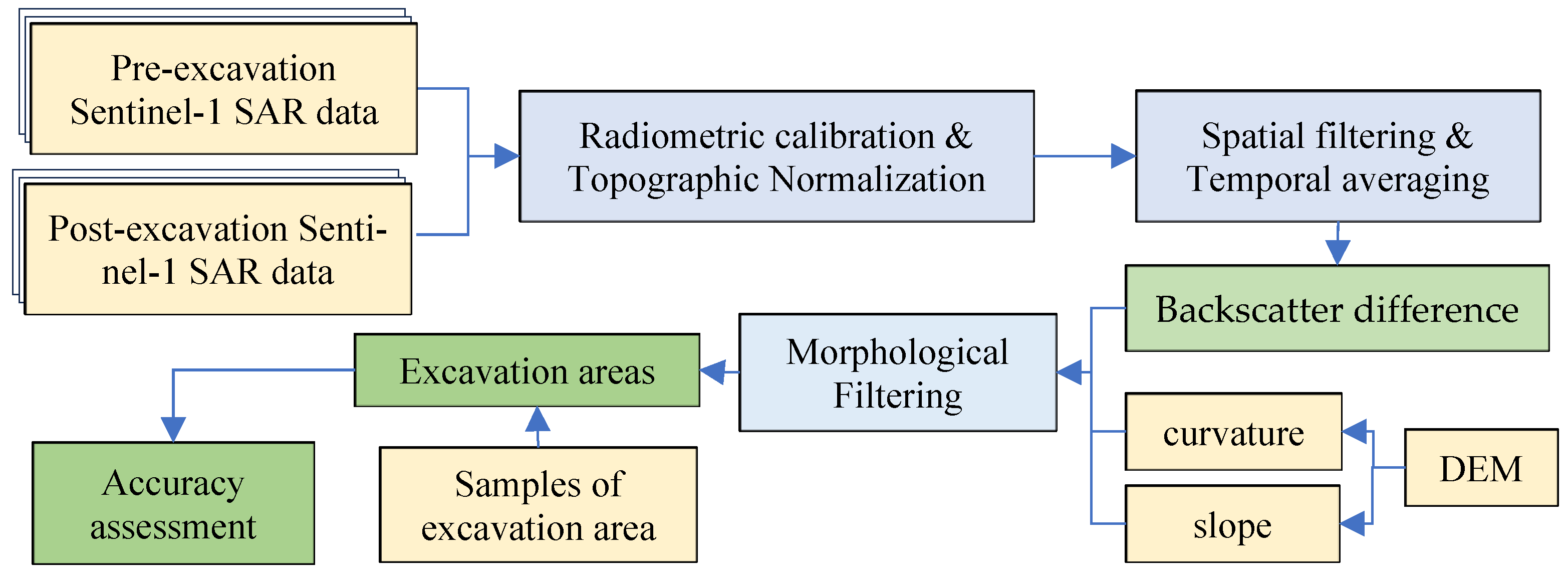

2.3. Methods

- (1)

- Multi-temporal change detection to gain excavation areas

- (2)

- Mapping spatiotemporal distribution of land creations using Random Forest

- (3)

- Enhanced SBAS-InSAR for Monitoring Engineering-Induced Subsidence

- (4)

- Accuracy analysis

3. Results

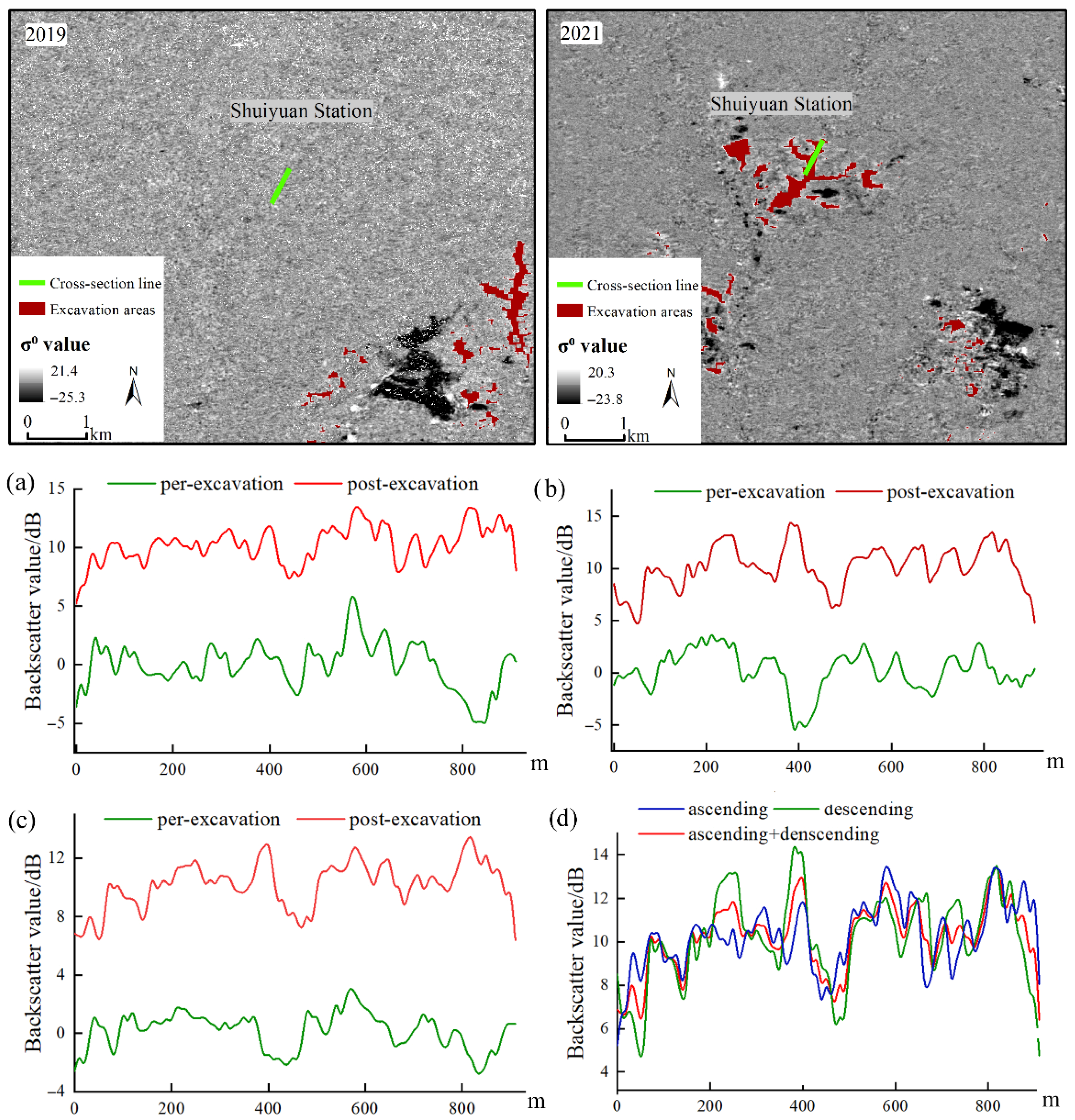

3.1. Analysis of Backscatter Coefficient Variations Before and After MELCPs

3.2. Dynamic Monitoring of Excavation Zones in Lanzhou North New Urban

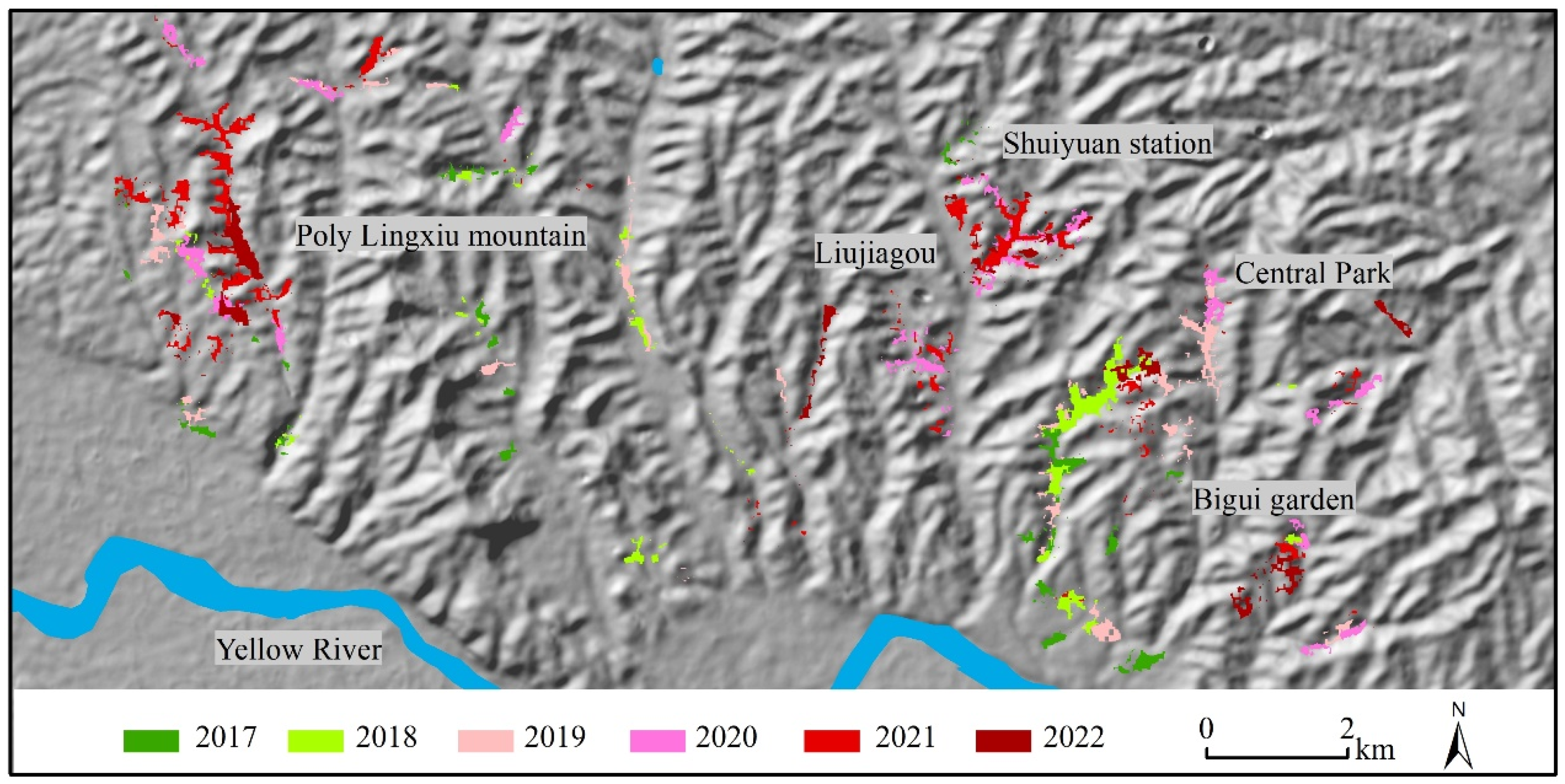

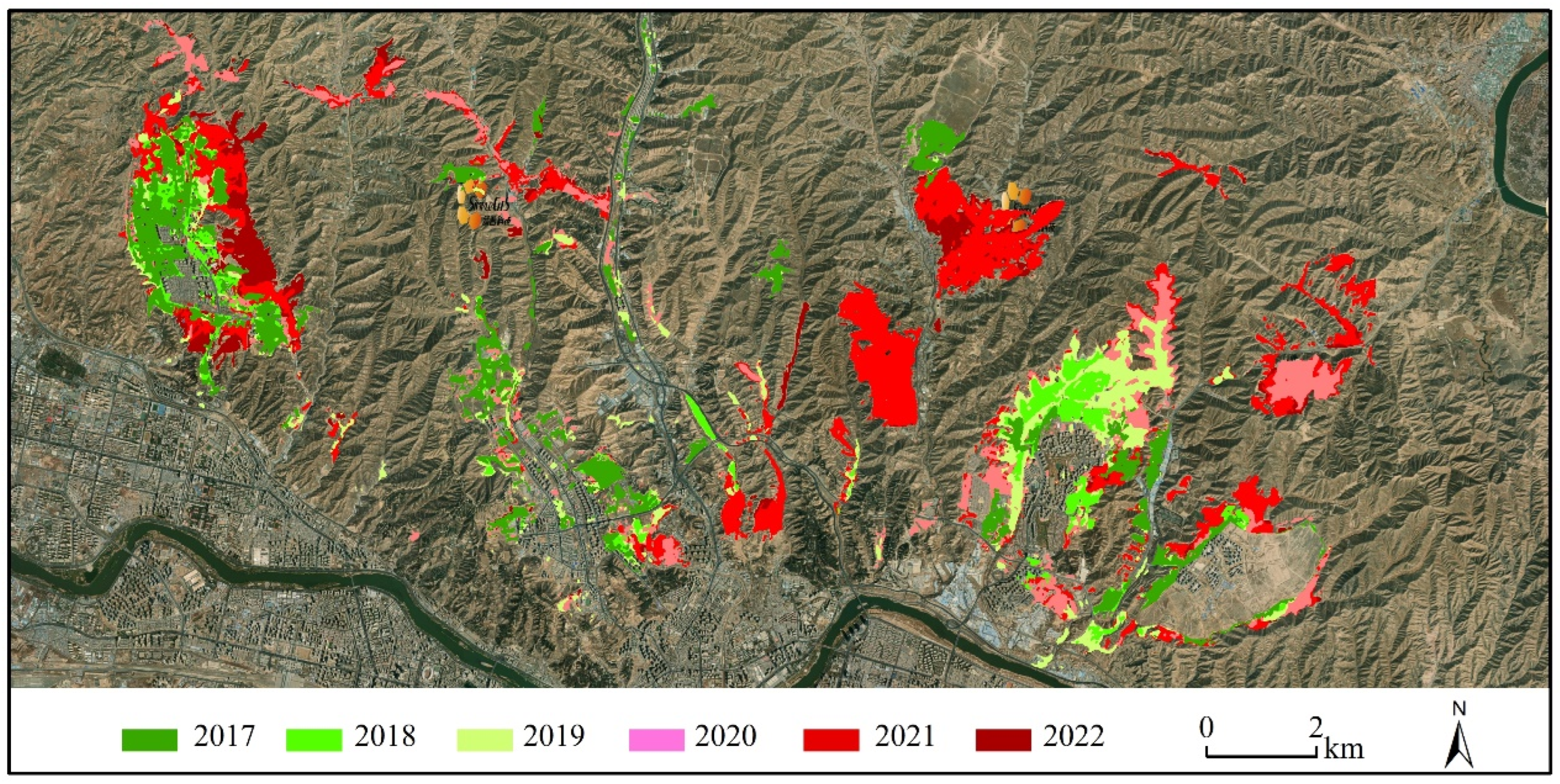

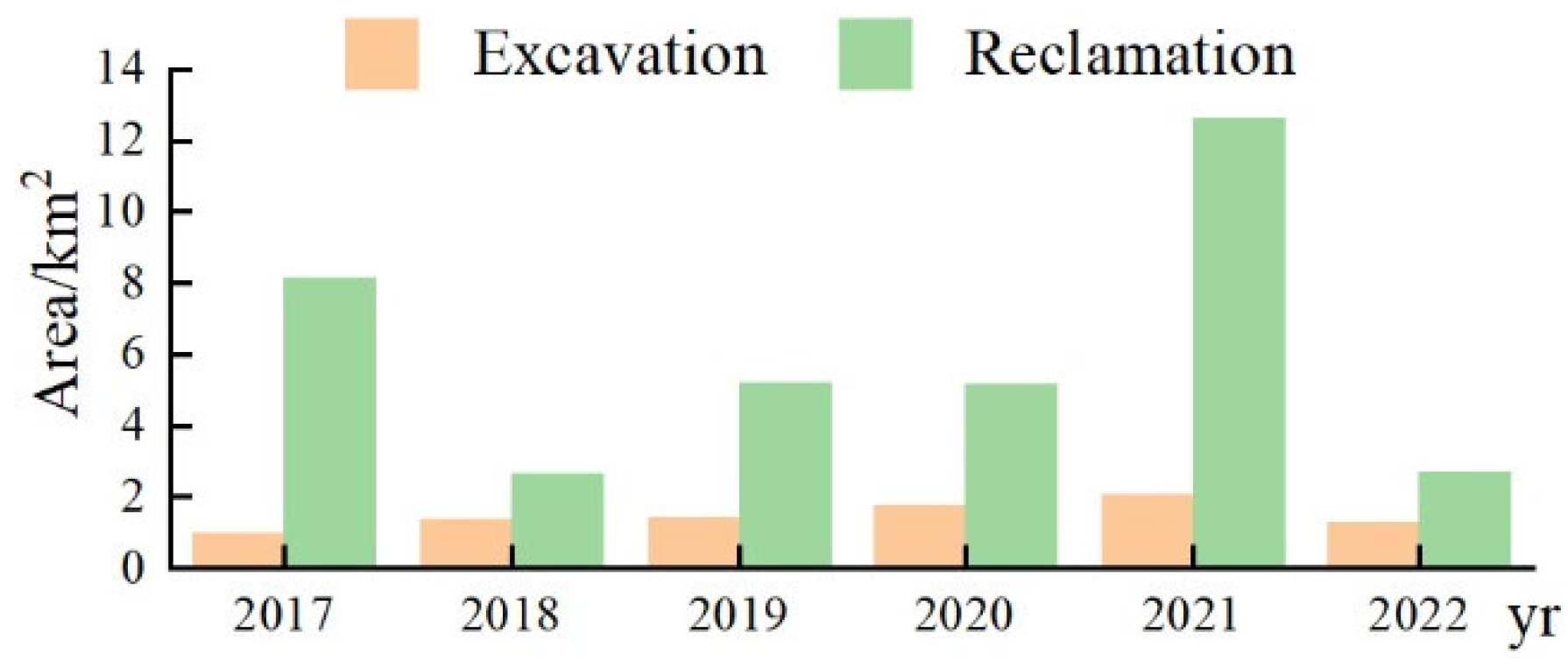

3.3. Evolution Trajectory of MELCPs in 2017–2022

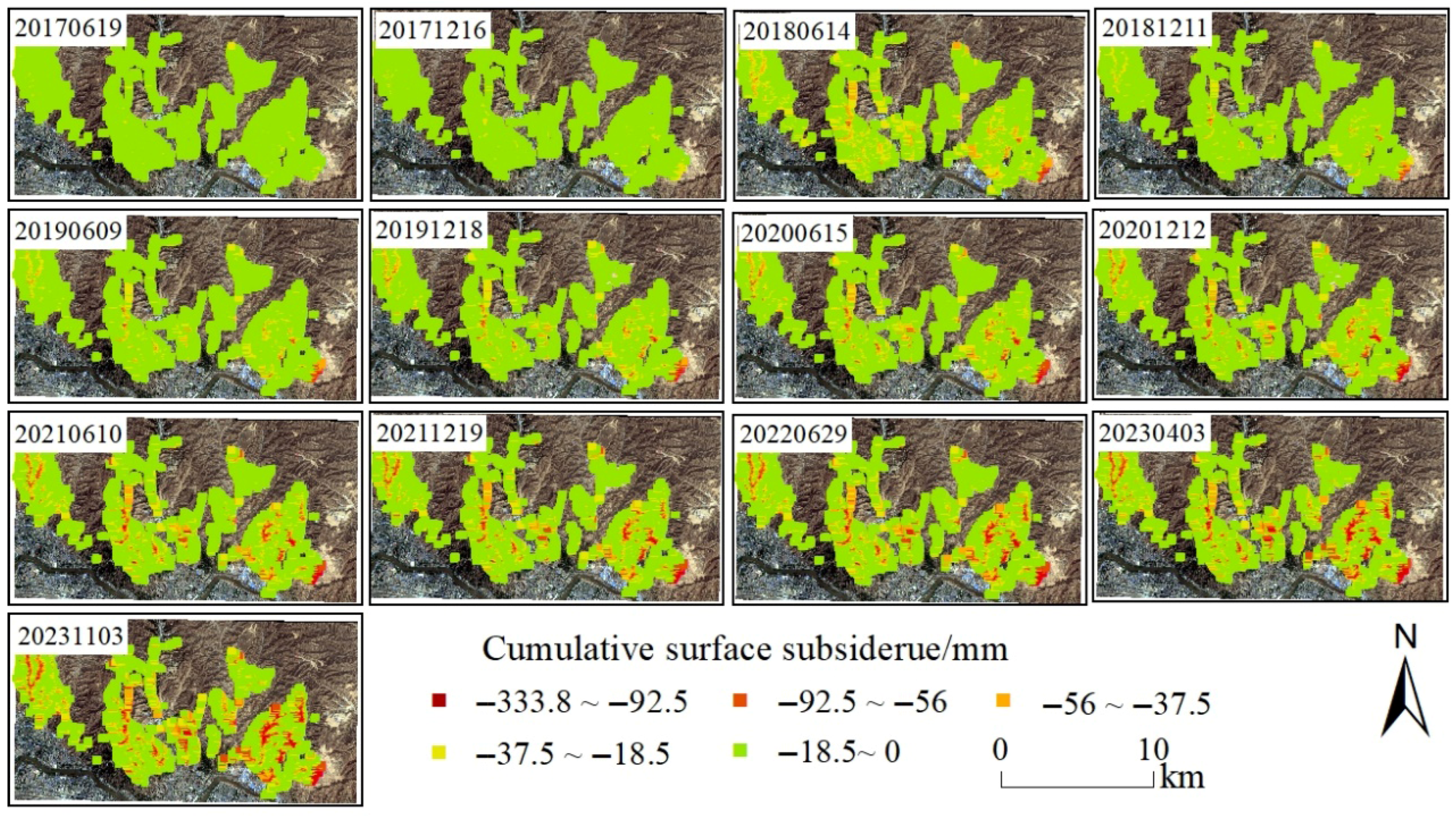

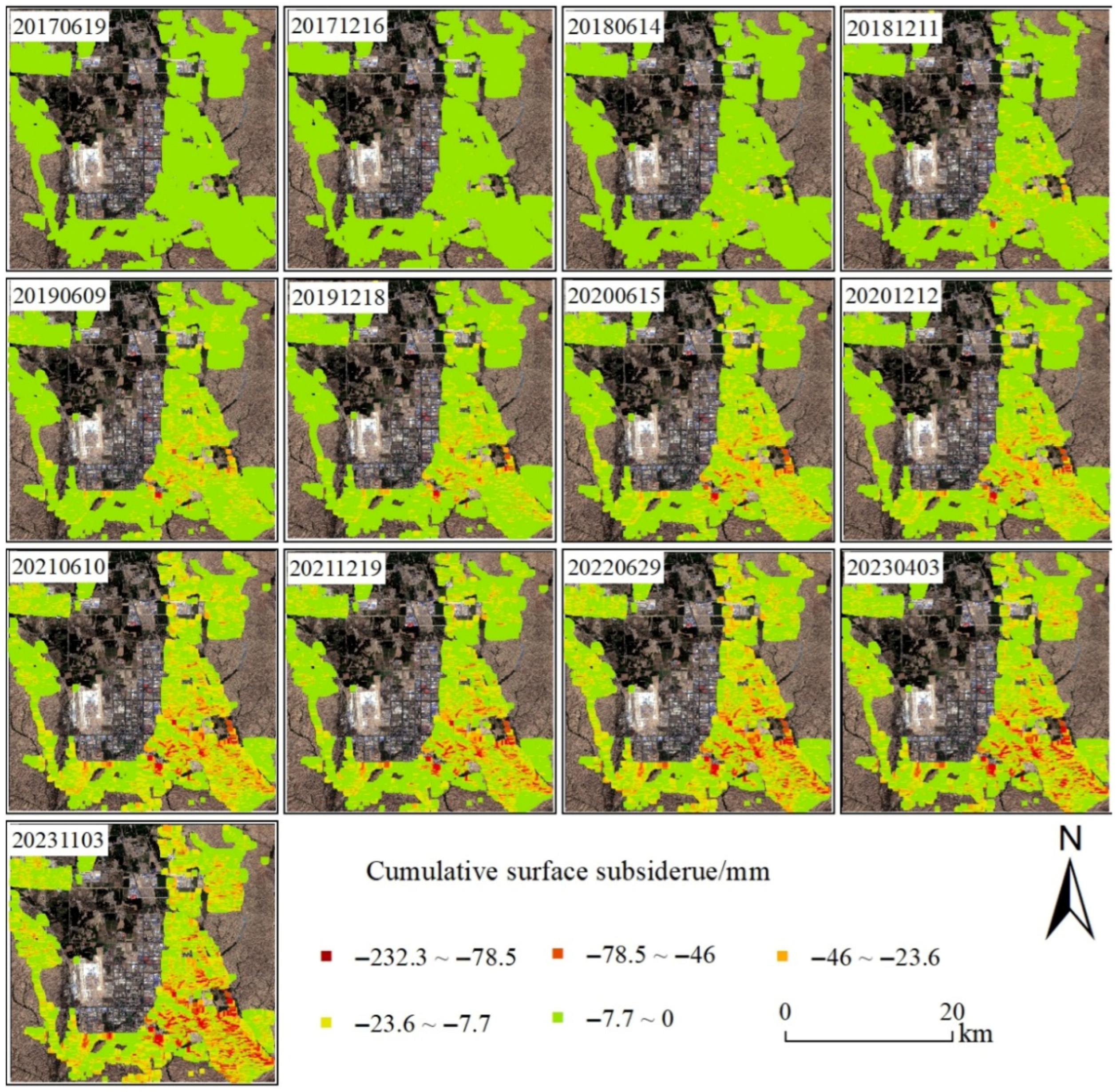

3.4. InSAR-Based Analysis of Engineering-Induced Subsidence Dynamics

4. Discussion

4.1. Accurate Extraction of MELCPs Driven by Multi-Source Data and Machine Learning

4.2. Unraveling the Hierarchical Mechanisms of MELCPs-Induced Land Subsidence

4.3. The Limitations of the Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seto, K.C.; Fragkias, M.; Güneralp, B.; Reilly, M.K. A meta-analysis of global urban land expansion. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angel, S.; Parent, J.; Civco, D.L.; Blei, A.; Potere, D. The dimensions of global urban expansion: Estimates and projections for all countries, 2000–2050. Prog. Plan. 2011, 75, 53–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Qian, H.; Wu, J. Environment: Accelerate research on land creation. Nature 2014, 510, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, C.; Chen, B.; Dai, W. Consistency evaluation of precipitable water vapor derived from ERA5, ERA-Interim, GNSS, and radiosondes over China. Radio Sci. 2019, 54, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firman, T. The continuity and change in mega-urbanization in Indonesia: A survey of Jakarta–Bandung Region (JBR) development. Habitat Int. 2009, 33, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.S.; Idrus, S.; Mohamed, A.F.; Taha, M.R.; Othman, M.R.; Ismail, S.M.F.S.; Ismail, S.M. Managing the Growing Kuala Lumpur Mega Urban Region for Livable City: The Sustainable Development Goals as Guiding Frame. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.; Xu, Q.; Wang, X. Vegetation response to large-scale mountain excavation and city construction projects on the Loess Plateau of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Cao, E.; Xie, Y. Integrating ecosystem services and landscape ecological risk into adaptive management: Insights from a western mountain-basin area, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 281, 111817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Yi, L.; Zuo, L.; Xu, J.; Hu, S.; Sun, F.; et al. Urban Expansion of China from the 1970s to 2020 Based on Remote Sensing Technology. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Fang, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, X. Assessing sustainability of urbanization by a coordinated development index for an Urbanization-Resources-Environment complex system: A case study of Jing-Jin-Ji region, China. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Torizin, J.; Wang, L. Identification and temporally-spatial quantification of geomorphic relevant changes by construction projects in loess landscapes: Case study Lanzhou City, NW China. Big Earth Data 2019, 3, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, A. Development Zones and Evolvement of Urban Spatial Structure. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2011, 11, 1529–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Bai, J.; Cheng, W. Mapping the dynamics of urban land creation from hilltop removing and gully filling Projects in the river-valley city of Lanzhou, China. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2022, 50, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. Urban land expansion and the transitional mechanisms in Nanjing, China. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B. Ecological and environmental effects of land-use changes in the Loess Plateau of China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 3769–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Anna, H.; Zhang, L. Spatial and Temporal Changes of Arable Land Driven by Urbanization and Ecological Restoration in China. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Y. Ecological vulnerability assessment and its driving force based on ecological zoning in the Loess Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Zhang, X.; Yan, S.; Chen, H. Estimating soil erosion response to land use/cover change in a catchment of the Loess Plateau, China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2018, 6, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hao, M.; Chen, S. Assessment of landslide susceptibility and risk factors in China. Nat. Hazards 2021, 108, 3045–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Shu, H.; Yan, B. Characteristic analysis and potential hazard assessment of reclaimed mountainous areas in Lanzhou, China. CATENA 2023, 221, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, K.M.; Calef, M.T.; Agram, P.S. Contextual uncertainty assessments for InSAR-based deformation retrieval using an ensemble approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 287, 113456–113470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Qiu, S.; Ye, S. Remote sensing of land change: A multifaceted perspective. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 282, 113266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melichar, M.; Didan, K.; Barreto-Muñoz, A.; Duberstein, J.N.; Jiménez Hernández, E.; Crimmins, T.; Li, H.; Traphagen, M.; Thomas, K.A.; Nagler, P.L. Random Forest Classification of Multitemporal Landsat 8 Spectral Data and Phenology Metrics for Land Cover Mapping in the Sonoran and Mojave Deserts. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, M.; Jiang, J. China’s high-resolution optical remote sensing satellites and their mapping applications. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 24, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gélis, I.; Lefèvre, S.; Corpetti, T. Siamese KPConv: 3D multiple change detection from raw point clouds using deep learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 197, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yao, S.; Tang, Y.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z. Shadow-aware decomposed transformer network for shadow detection and removal. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 156, 110771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Niu, S.; Ciais, P.; Janssens, I.A.; Chen, J.; Ammann, C.; Arain, A.; Blanken, P.D.; Cescatti, A.; Bonal, D.; et al. Joint control of terrestrial gross primary productivity by plant phenology and physiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2788–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Xu, Q.; Pu, C. InSAR Time Series Monitoring and Analysis of Land Deformation After Mountain Excavation and City Construction in Lanzhou New Area. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2024, 49, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, W.L.; Fadhillah, M.F.; Won, J.S.; Park, Y.C.; Lee, C.W. Advanced time-series InSAR analysis to estimate surface deformation and utilization of hybrid deep learning for susceptibility mapping in the Jakarta metropolitan region. GISci. Remote Sens. 2025, 62, 2465349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, B.; Gao, H. Drifting Ionospheric Scintillation Simulation for L-Band Geosynchronous SAR. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosetto, M.; Monserrat, O.; Cuevas-González, M. Persistent Scatterer Interferometry: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydi, S.T.; Shah-Hosseini, R.; Hasanlou, M. New framework for hyperspectral change detection based on multi-level spectral unmixing. Appl. Geomat. 2021, 13, 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Y. Deep Learning Ensemble for Hyperspectral Image Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 1882–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhang, G.; Luo, Y.; Liang, C.; Duan, J.; Ran, S.; Zhang, J. Wavefield Separation-Driven High-Precision Deep-Learning Karst Caves Recognition Method. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutebuch, S.E.; McGaughey, R.J.; Andersen, H.E.; Carson, W.W. Accuracy of a high-resolution lidar terrain model under a conifer forest canopy. Can. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 29, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ergun, K.; Cherkasova, L.; Rosing, T.S. Optimizing Sensor Deployment and Maintenance Costs for Large-Scale Environmental Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Comput. Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 2020, 39, 3918–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, A.; Ahmadi, A.; Daccache, A.; Drechsler, K. Actual Evapotranspiration from UAV Images: A Multi-Sensor Data Fusion Approach. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, V.; Tosan, M.; Huang, J.J.; Gebremichael, M.; Kantoush, S.A.; Dastourani, M. Advances in multi-source data fusion for precipitation estimation: Remote sensing and machine learning perspectives. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2025, 270, 105253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Q.; Liu, M.; Liu, B.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, K. Mapping the forests and their spatiotemporal changes in the Yellow River Basin (Gansu section) in China from 2008 to 2018. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 58, 2451046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, P.; Dell’acqua, F.; Houshmand, B. Comparison and fusion of LIDAR and InSAR digital elevation models over urban areas. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 4289–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugiraneza, T.; Hafner, S.; Haas, J.; Ban, Y. Monitoring urbanization and environmental impact in Kigali, Rwanda using Sentinel-2 MSI data and ecosystem service bundles. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 109, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia Ortiz, J.A.; Martínez-Graña, A.M.; Méndez, L.M. Evaluation of Susceptibility by Mass Movements through Stochastic and Statistical Methods for a Region of Bucaramanga, Colombia. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, A.; Bekaert, D.; Spaans, K.; Arıkan, M. Recent advances in SAR interferometry time series analysis for measuring crustal deformation. Tectonophysics 2012, 514–517, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.; Snoeij, P.; Geudtner, D. GMES Sentinel-1 mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S. Sentinel-2: ESA’s optical high-resolution mission for GMES operational services. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main-Knorn, M.; Pflug, B.; Louis, J. Sen2Cor for Sentinel-2. In Proceedings of the Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XXIII, Warsaw, Poland, 11–13 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, N.; Baumann, M.; Ehammer, A. A review of the application of optical and radar remote sensing data fusion to land use mapping and monitoring. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer-Marschallinger, B.; Cao, S.; Navacchi, C.; Freeman, V.; Reuß, F.; Geudtner, D.; Rommen, B.; Vega, F.C.; Snoeij, P.; Attema, E.; et al. The normalised Sentinel-1 Global Backscatter Model, mapping Earth’s land surface with C-band microwaves. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, S.; Woodcock, C.E. Improvement and expansion of the Fmask algorithm: Cloud, cloud shadow, and snow detection for Landsats 4–7, 8, and Sentinel 2 images. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 159, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.E.; Yang, Z.; Gorelick, N. Implementation of the LandTrendr algorithm on Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiminia, H.; Salehi, B.; Mahdianpari, M. Google Earth Engine for geo-big data applications: A meta-analysis and systematic review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 164, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehman, S.V. Sampling designs for accuracy assessment of land cover. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 5243–5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, T.G. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, RG2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovolo, F.; Bruzzone, L. A theoretical framework for unsupervised change detection based on change vector analysis in the polar domain. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2007, 45, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rignot, E.J.M.; van Zyl, J.J. Change detection techniques for ERS-1 SAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1993, 31, 896–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.A.; Thomas, C.; Halpin, P. Automating offshore infrastructure extractions using synthetic aperture radar & Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 233, 111412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, X.; Choy, S. Detecting heavy rainfall using anomaly-based percentile thresholds of predictors derived from GNSS-PWV. Atmos. Res. 2022, 265, 105912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Uriarte, R.; Alvarez de Andrés, S. Gene selection and classification of microarray data using random forest. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorutti, B.; Michel, B.; Saint-Pierre, P. Correlation and variable importance in random forests. Stat. Comput. 2017, 27, 659–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, P.; Wright, M.; Boulesteix, A.L. Hyperparameters and Tuning Strategies for Random Forest. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, e1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scornet, E. Random Forests and Kernel Methods. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2016, 62, 1485–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colesanti, C.; Wasowski, J. Investigating landslides with space-borne Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) interferometry. Eng. Geol. 2006, 88, 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisinger, C. Precise three-dimensional stereo localization of corner reflectors in mountainous terrain using TerraSAR-X. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 1782–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zan, F.; Guarnieri, A.M. TOPSAR: Terrain observation by progressive scans. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 2352–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prats-Iraola, P. On the processing of very high resolution spaceborne SAR data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2012, 52, 6003–6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, G.; Bao, X. Eliminating geometric distortion with dual-orbit Sentinel-1 SAR fusion for accurate glacial lake extraction in Southeast Tibet Plateau. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 136, 104329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli, C.; Lavalle, M.; Pierdicca, N. Vegetation height from L-band SAR backscatter and interferometric temporal coherence measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 328, 114879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardino, P.; Fornaro, G.; Lanari, R. A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential SAR interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2002, 40, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, R. Improving InSAR geodesy using Global Atmospheric Models. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2014, 119, 2324–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, H.; Amelung, F. InSAR Bias and Uncertainty Due to the Systematic and Stochastic Tropospheric Delay. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2015, 120, 8758–8773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, R.; Grandin, R.; Lasserre, C.; Doin, M.P.; Peltzer, G. Systematic InSAR tropospheric phase delay corrections from global meteorological reanalysis data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L17311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebker, H.A.; Villasenor, J. Decorrelation in Interferometric Radar Echoes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2010, 30, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, A.; Lanari, R. On the Extension of the Minimum Cost Flow Algorithm for Phase Unwrapping of Multitemporal Differential SAR Interferograms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 44, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantrasirichai, N.; Biggs, J.; Albino, F. Application of machine learning to classification of volcanic deformation in routinely generated InSAR data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2018, 123, 6592–6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P. Good Practices for Assessing Accuracy and Estimating Area of Land Change. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Name | Distinctive Features | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bare land | High reflectance in visible bands and absence of vegetation characteristics |  |

| 2 | Cropland | Regular geometric boundaries with significant seasonal variations |  |

| 3 | Buildings | Regular geometric shapes with homogeneous textures and high reflectance in visible bands |  |

| 4 | MELCPs areas | Show clear artificial modification traces with rough surfaces, typically exhibiting platform-like distributions, distinct image textures |  |

| 5 | Water bodies | Strong absorption in near-infrared bands, natural shapes, and smooth textures |  |

| 6 | Forests | High near-infrared reflectance, coarse textures, and distinct canopy structures |  |

| 7 | Grassland | Spectral characteristics similar to vegetation but with lower near-infrared reflectance than forests |  |

| Datasets | Feature | Variable Description |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral feature | B2, B3, B4, B5, B8, B8a, B11 | blue, green, red, red edge, NIR, NNIR, SWIR |

| Index feature | RVI | |

| NDVI | ||

| NDWI | ||

| NDBI | ||

| MSAVI | ||

| EVI | ||

| BSI | ||

| Topographic feature | DEM, Slope | / |

| Polarimetric feature | , | / |

| Textural feature | Second moment | |

| Contrast | ||

| Correlation | ||

| Variance | ||

| Inverse variance | ||

| Entropy |

| Accuracy Metrics | Ascending | Descending | Ascending + Descending |

|---|---|---|---|

| OA/% | 78.7 | 72.6 | 87.1 |

| Kappa | 0.75 | 0.69 | 0.85 |

| Periods (yr) | Initial Phase/Scene | Later Phase/Scene | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ascending Orbit | Descending Orbit | Ascending Orbit | Descending Orbit | |

| 2017 | 8 | 12 | 24 | 13 |

| 2018 | 15 | 8 | 22 | 30 |

| 2019 | 15 | 18 | 24 | 26 |

| 2020 | 16 | 22 | 27 | 32 |

| 2021 | 15 | 25 | 24 | 25 |

| 2022 | 12 | 14 | 15 | 21 |

| Land Cover Types | Metrics (%) | Seven Experimental Schemes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | ||

| MELCPs areas | PA | 84.2 | 87.0 | 83.0 | 86.0 | 86.5 | 79.1 | 92.1 |

| UA | 73.4 | 82.0 | 75.0 | 80.0 | 83.2 | 76.0 | 92.8 | |

| Buildings | PA | 85.9 | 80.4 | 82.1 | 83.9 | 79.3 | 79.1 | 86.7 |

| UA | 76.7 | 80.8 | 86.6 | 75.9 | 82.1 | 74.3 | 86.2 | |

| Water bodies | PA | 91.0 | 85.2 | 84.1 | 86.9 | 83.6 | 83.2 | 90.9 |

| UA | 83.9 | 88.7 | 83.8 | 89.9 | 87.3 | 85.1 | 91.3 | |

| Grassland | PA | 78.9 | 80.0 | 75.0 | 73.8 | 78.9 | 75.8 | 82.5 |

| UA | 76.7 | 77.0 | 88.6 | 68.9 | 85.7 | 76.0 | 79.7 | |

| Forests | PA | 72.8 | 85.0 | 79.9 | 80.3 | 79.6 | 74.5 | 83.0 |

| UA | 70.2 | 71.6 | 85.9 | 78.7 | 74.7 | 70.8 | 82.4 | |

| Bare land | PA | 72.9 | 79.7 | 80.5 | 81.9 | 85.4 | 82.1 | 86.5 |

| UA | 75.3 | 89.9 | 74.9 | 75.3 | 81.7 | 79.2 | 87.1 | |

| Cropland | PA | 72.9 | 79.7 | 80.5 | 81.9 | 85.4 | 82.07 | 86.5 |

| UA | 75.3 | 89.9 | 74.9 | 75.3 | 81.7 | 79.2 | 87.1 | |

| Times | Seven Experimental Schemes (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | ||||||||

| OA | K | OA | K | OA | K | OA | K | OA | K | OA | K | OA | K | |

| 1 | 82.2 | 78.1 | 82.6 | 76.4 | 90.9 | 88.0 | 91.0 | 88.3 | 88.3 | 85.0 | 87.2 | 84.3 | 93.9 | 93.1 |

| 2 | 88.0 | 84.3 | 83.1 | 77.1 | 85.3 | 81.1 | 91.0 | 88.3 | 89.7 | 86.3 | 86.0 | 82.9 | 93.0 | 91.0 |

| 3 | 84.3 | 80.0 | 93.0 | 91.0 | 82.1 | 80.0 | 90.2 | 86.0 | 92.9 | 90.1 | 86.0 | 82.9 | 93.0 | 91.0 |

| 4 | 82.0 | 78.3 | 90.3 | 87.6 | 79.3 | 74.3 | 88.3 | 85.1 | 84.0 | 83.1 | 81.4 | 75.0 | 88.1 | 84.9 |

| 5 | 81.7 | 75.4 | 89.2 | 86.4 | 81.0 | 77.1 | 90.0 | 86.0 | 87.9 | 84.9 | 83.9 | 80.1 | 88.1 | 84.9 |

| Avg. | 83.6 | 79.2 | 87.6 | 83.7 | 83.7 | 80.1 | 90.1 | 86.7 | 88.5 | 85.8 | 84.9 | 81.4 | 91.2 | 88.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Niu, Q.; Lei, J.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, L. Dynamic Monitoring and Analysis of Mountain Excavation and Land Creation Projects in Lanzhou Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020273

Niu Q, Lei J, Fang Q, Zhang L. Dynamic Monitoring and Analysis of Mountain Excavation and Land Creation Projects in Lanzhou Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020273

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Quanfu, Jiaojiao Lei, Qiong Fang, and Lifeng Zhang. 2026. "Dynamic Monitoring and Analysis of Mountain Excavation and Land Creation Projects in Lanzhou Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Machine Learning" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020273

APA StyleNiu, Q., Lei, J., Fang, Q., & Zhang, L. (2026). Dynamic Monitoring and Analysis of Mountain Excavation and Land Creation Projects in Lanzhou Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020273