Electromagnetic Scattering Characteristic-Enhanced Dual-Branch Network with Simulated Image Guidance for SAR Ship Classification

Highlights

- We propose a multi-parameter adjustable spaceborne SAR image simulation method and innovatively introduce the concept of BNM.

- We propose SeDSG, which achieves the efficient extraction and adaptive fusion of SAR image features and BNM features.

- The proposed simulation method significantly expands training sample diversity and mitigates the shortage of labeled SAR images.

- The proposed network enhances detail recognition capability and structural perception accuracy, offering a practical solution for spaceborne SAR ship classification.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

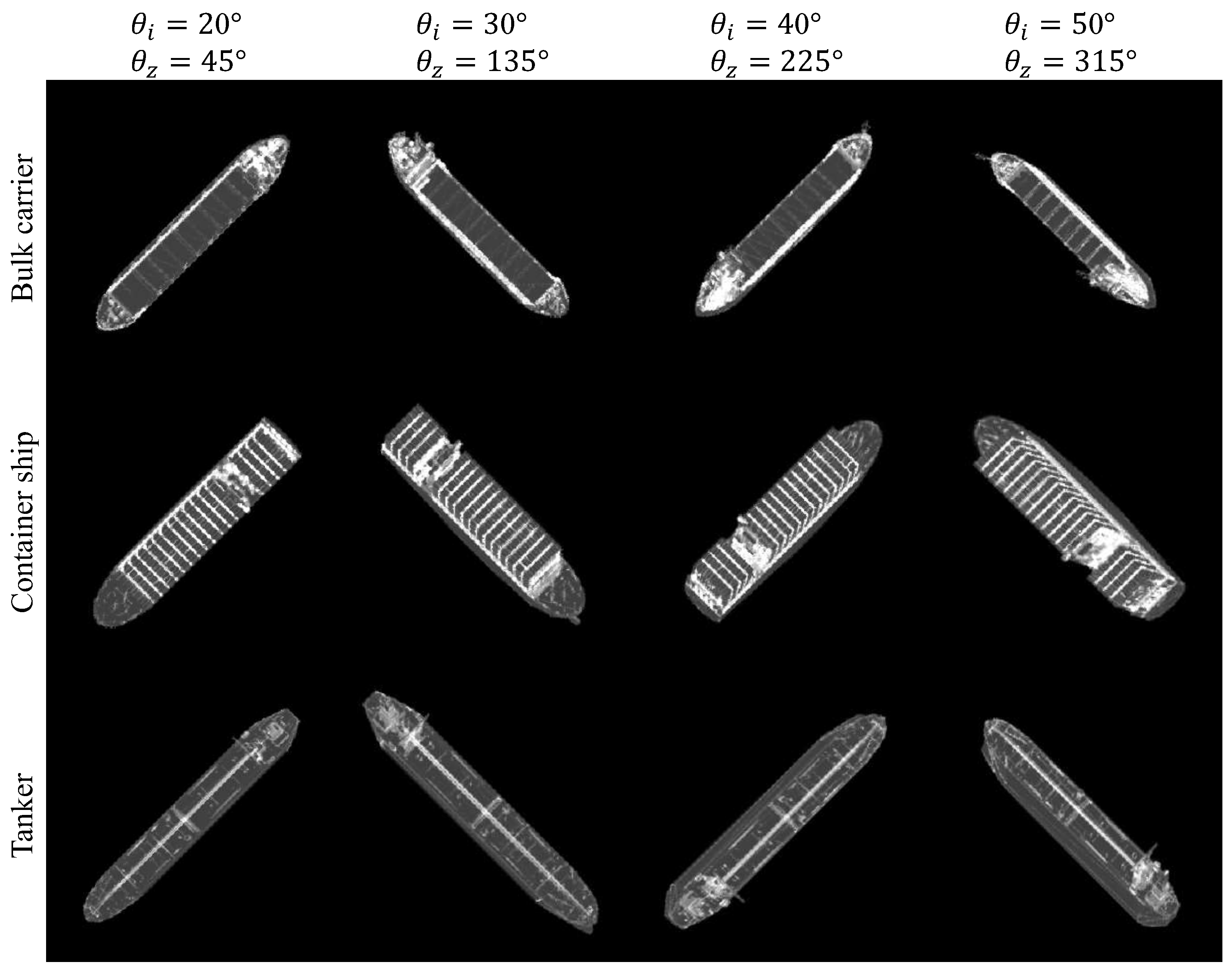

- To enhance the adaptability of the dataset to actual scenarios, this paper proposes a ship image simulation technology for spaceborne SAR systems. By constructing a multi-parameter adjustable simulation framework, it can flexibly generate simulation images covering different ship types, namely bulk carriers, container ships, and tankers, under diverse satellite imaging parameters, such as resolution, incident angle, and polarization mode, effectively solving the problems of the lack of labeled SAR image data and the imbalance of category distribution. On this basis, this paper innovatively introduces the concept of BNM. By recording the average reflection times of rays in the corresponding area of each pixel point in the image, this paper constructs an enhanced feature map capable of precisely characterizing the three-dimensional structural features and local scattering characteristics of the ship.

- (2)

- To systematically verify the practical value of simulation images and deeply explore their multi-dimensional feature information, this paper proposes an electromagnetic scattering characteristic-enhanced dual-branch network with simulated image guidance for SAR ship classification (SeDSG). This framework achieves the fusion of SAR image features and the structural features of BNM by constructing a parallel architecture of the main branch and the auxiliary branch. The main branch adopts the improved ResNet-50 backbone network to extract the grayscale, contour, and texture features of the image, while the auxiliary branch leverages the SlimHRNet-Backbone to prioritize the electromagnetic scattering characteristics within the BNM and establish the correlation between it and the 3D structural attributes of the target. Finally, multi-scale feature fusion is achieved through the cross-branch feature pyramid fusion module. Experiments show that the simulation images generated by the proposed method not only significantly expand the diversity of training samples, but also effectively improve the detail identification ability and structure perception accuracy of the ship classification model, which provides key data support and technical innovation for spaceborne SAR ship classification.

2. Related Works

2.1. Ship Classification Methods Based on SAR Images

2.2. Methods Assisted by Electromagnetic Simulation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Generation of Bounce Number Map (BNM)

- Extract key information such as dimensions and structure from the target model file, and represent it using an appropriate data structure to facilitate computer processing;

- Construct a ray pool based on conditions including resolution and satellite parameters, and complete the accurate determination of target incidence points;

- Trace all ray tubes using the GO method until the rays no longer intersect the target or reach the preset upper limit of reflection times, and synchronously record the number of ray reflections during the tracing process to provide data support for generating the BNM;

- Based on the calculation results of the electromagnetic field when the rays depart from the target surface, comply with the electromagnetic field equivalence principle, and combine the polarization directions of electromagnetic wave transmission and reception to calculate the RCS of the entire target using the PO method.

3.1.1. Target Modeling and Incidence Point Determination

3.1.2. Ray Tracing Algorithm

- Based on the pre-divided grid structure, adjacent triangular facets are assigned to their corresponding grid cells to clarify the reflection positions of rays, thereby establishing the mapping relationship between rays and the grid.

- In the ray tracing phase, a bidirectional path tracing algorithm is employed to record the propagation path of each ray in real time. Upon the intersection of a ray with the target surface, the reflection count statistic of the corresponding grid point is updated. This ensures that each reflection process is accurately recorded.

- After the completion of ray tracing, for each grid point, the reflection counts of all rays passing through that location are summed. The average bounce number is then calculated by dividing this total by the number of valid rays, which is subsequently used as the bounce number index for the grid point.

- By generating a bounce number distribution map on the target surface, the computed data is visualized to facilitate a more intuitive presentation of the scattering counts at different positions on the target.

3.1.3. Electromagnetic Calculation

3.2. Design of Dual-Branch Network Architecture

- (1)

- Deviations exist in the fine structures and material properties between 3D models and real ships, and the computer processing technology for the models requires further improvement;

- (2)

- Dynamic changes in spatiotemporal conditions lead to uncertain fluctuations in ship loading states, which undermines the adaptability of simulated images to actual scenarios;

- (3)

- Simulated images lack sufficient accuracy in simulating imaging noise and complex background elements, such as the sea surface environment, making it difficult to fully cover various practical application scenarios.

3.2.1. Main Branch Network

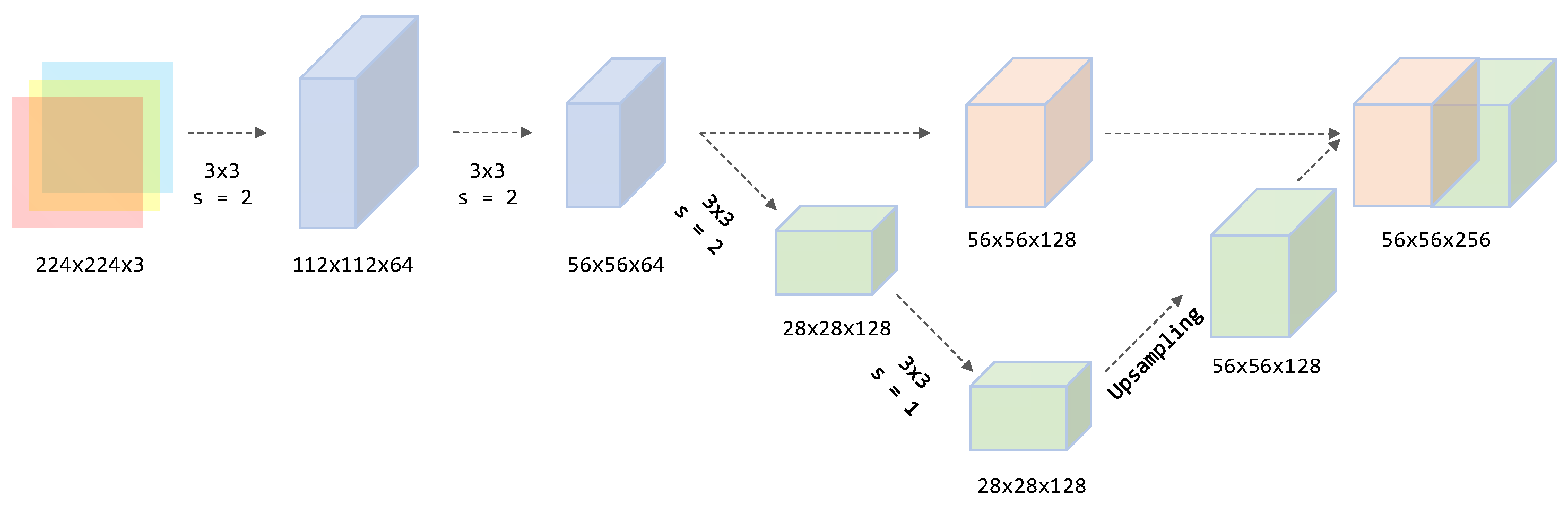

3.2.2. Auxiliary Branch Network

- (1)

- Adaptation to ship scale differences. There are significant differences in the sizes of different types of ships, and the classification of the auxiliary branch mainly relies on specific structures. The details of small ships can be clearly presented at 1/4 resolution, while the global features of large ships can still be completely retained at 1/8 resolution. The dual-branch design can accurately cover this scale range, avoiding noise introduced by excessive downsampling in HRNet due to information loss. It can not only extract the detailed features of ships but also capture the global geometric features of the entire hull, such as shape and contour.

- (2)

- Reduction of computational complexity. Compared with the original network, the proposed SlimHRNet-Backbone has much fewer parameters and lower computational complexity, reducing the requirement for device memory. It can be efficiently trained on ordinary GPUs, avoiding out-of-memory errors and improving feature extraction efficiency.

- (3)

- Compatibility with subsequent modules. The output channel number of this backbone network is uniformly 256, which fully matches the input channel requirement of the subsequent network. Meanwhile, streamlining the number of branches and the phase design reduces the difficulty of dimension alignment and channel matching during feature fusion.

3.2.3. Dual-Branch Feature Fusion Module and Classifier

- (1)

- Adapting to differences between simulated images and SAR images. Generally speaking, compared with measured images, the BNM generated in this paper is characterized by higher resolution and more sufficient detail representation, and moreover, it achieves higher image clarity due to being free from noise interference. This enables the model to automatically increase the auxiliary branch feature weight to ensure classification performance when real images have low resolution or severe interference.

- (2)

- Addressing the scenario where the simulated image dataset is unavailable. Only measured SAR images are input in both validation and inference phases, rendering auxiliary branch features invalid and requiring the model to achieve excellent classification results using only the measured dataset. Therefore, during training, the model proactively optimizes the feature extraction capability of the main branch, enhances the discriminative power of SAR image features, increases their weight proportion, and guides the main branch to actively learn the local scattering features of the auxiliary branch. This enables the main branch to fully internalize the effective information from the auxiliary branch, ensuring accurate classification even in the absence of simulated data.

4. Results

4.1. Experimental Data Description

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Performance of SeDSG

4.4. Comparison with Other Models

- (a)

- On the OpenSARShip dataset, although the accuracy of SeDSG (85.89%) is slightly lower than that of DBDN (87.62%), it is significantly superior to classical models such as AlexNet (82.41%) and VGG-16 (82.00%). Furthermore, after achieving class balance through data augmentation, all evaluation metrics are higher than those of DBDN, verifying the effectiveness of the network on low-resolution datasets.

- (b)

- On the FUSAR-Ship dataset, the accuracy (91.89%) and F1-Score (91.88%) of SeDSG far exceed those of all comparative models, representing a 2.7 percentage point improvement compared to the second-best model VGG-16 (89.19%). Additionally, higher accuracy can be achieved through traditional data augmentation methods, which effectively improves the classification performance on datasets with a small number of samples.

- (c)

- On the SRSDD dataset, SeDSG achieves the best performance with an accuracy of 97.41% and an F1-Score of 97.43%, which is higher than that of state-of-the-art models such as Wide-ResNet-50 (96.98%), demonstrating its prominent advantages in high-resolution SAR ship image classification tasks.

4.5. Validation of Model Pretraining Capability

4.6. Ablation Study

- (a)

- When the CBAM module is exclusively removed, the classification accuracy of the OpenSARShip dataset drops to 84.66%, while that of the FUSAR-Ship dataset decreases to 81.08% with a reduction of more than 10% compared to the SeDSG model. This result demonstrates that for datasets with high image resolution but scarce samples, the CBAM module plays a crucial role in improving classification performance by focusing on feature enhancement in the channel dimension.

- (b)

- Upon exclusive removal of the PPNet, the classification accuracies of the two datasets are 85.07% and 86.49%, respectively, both lower than the performance level of the SeDSG. This illustrates that the PPNet module optimizes the feature extraction process in the spatial dimension through multi-scale feature fusion, enabling it to simultaneously capture detailed features and global features, thereby achieving superior feature representation.

- (c)

- Following the exclusive removal of the fusion attention module and with the weights of the main branch and auxiliary branch fixed at 0.7 and 0.3, the accuracies of the two datasets are 83.03% and 89.19%, respectively. This confirms that the fusion attention module, by dynamically adjusting branch weights and realizing cross-dimensional feature interaction, can prompt the main branch to more efficiently enhance its feature extraction capability, deeply mine the category-shared features in images, and ultimately achieve a significant improvement in classification performance.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, H.; Xu, G.; Xia, X.G.; Li, T.; Yu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xing, M.; Hong, W. Enhanced Matrix Completion Method for Superresolution Tomography SAR Imaging: First Large-Scale Urban 3-D High-Resolution Results of LT-1 Satellites Using Monostatic Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 22743–22758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Prats-Iraola, P.; Younis, M.; Krieger, G.; Hajnsek, I.; Papathanassiou, K.P. A tutorial on synthetic aperture radar. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2013, 1, 6–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen-Ting, C.; Xiang-Wei, X.; Ke-Feng, J.I. A Survey of Ship Target Recognition in SAR Images. Mod. Radar 2012, 34, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H. Ship Classification Based on Sidelobe Elimination of SAR Images Supervised by Visual Model. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf21), Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–14 May 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzi, R.; Raney, R.; Charbonneau, F. On the use of permanent symmetric scatterers for ship characterization. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2004, 42, 2039–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margarit, G.; Tabasco, A. Ship Classification in Single-Pol SAR Images Based on Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2011, 49, 3129–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Ji, K.; Zou, H.; Chen, W.; Sun, J. Ship Classification in TerraSAR-X Images with Feature Space Based Sparse Representation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2013, 10, 1562–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, X.; Ji, K.; Zhou, S.; Xing, X.; Zou, H. 2D comb feature for analysis of ship classification in high resolution SAR imagery. Electron. Lett. 2017, 53, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Z.; Kefeng, J.; Xiangwei, X.; Wenting, C.; Huanxin, Z. Ship Classification with High Resolution TerraSAR-X Imagery Based on Analytic Hierarchy Process. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2013, 2013, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Wu, F.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, B.; Tang, Y. A Novel Hierarchical Ship Classifier for COSMO-SkyMed SAR Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2014, 11, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makedonas, A.; Theoharatos, C.; Tsagaris, V.; Anastasopoulos, V.; Costicoglou, S. Vessel classification in COSMO-SkyMed SAR data using hierarchical feature selection. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, XL-7/W3, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Yin, J.; Yang, J. Ship Detection for PolSAR Images via Task-Driven Discriminative Dictionary Learning. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentes, C.; Velotto, D.; Tings, B. Ship Classification in TerraSAR-X Images with Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 43, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldin, R.J. SAR Target Recognition with Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Applied Imagery Pattern Recognition Workshop (AIPR), Washington, DC, USA, 9–11 October 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X. Injection of Traditional Hand-Crafted Features into Modern CNN-Based Models for SAR Ship Classification: What, Why, Where, and How. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Ke, X.; Yan, Y.; Luo, D.; Cui, F.; Peng, H.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T. Laplace & LBP feature guided SAR ship detection method with adaptive feature enhancement block. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IMCEC), Chongqing, China, 24–26 May 2024; Volume 6, pp. 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Gao, G. Divergence to Concentration and Population to Individual: A Progressive Approaching Ship Detection Paradigm for Synthetic Aperture Radar Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Xiao, P.; Wang, H. MobileShuffle: An Efficient CNN Architecture for Spaceborne SAR Scene Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 4015705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.N.; Zeng, G.Q.; Lu, K.D.; Geng, G.G.; Weng, J. MoAR-CNN: Multi-Objective Adversarially Robust Convolutional Neural Network for SAR Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2025, 9, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Sun, R.; Kong, Y.; Chang, W.; Sun, C.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Meng, Z.; Wang, F. CPINet: Towards A Novel Cross-Polarimetric Interaction Network for Dual-Polarized SAR Ship Classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusk, A.; Abulaitijiang, A.; Dall, J. Synthetic SAR Image Generation using Sensor, Terrain and Target Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of EUSAR 2016: 11th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, Hamburg, Germany, 6–9 June 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Malmgren-Hansen, D.; Kusk, A.; Dall, J.; Nielsen, A.A.; Engholm, R.; Skriver, H. Improving SAR Automatic Target Recognition Models with Transfer Learning from Simulated Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1484–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tan, Z.; Su, N. A Data Augmentation Strategy Based on Simulated Samples for Ship Detection in RGB Remote Sensing Images. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Feng, S.; Zhao, C.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ji, K. MGSFA-Net: Multiscale Global Scattering Feature Association Network for SAR Ship Target Recognition. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 4611–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Xu, G.; Pei, H.; Qiao, Y.; Yu, H.; Hong, W. Dual-Stream Manifold Multiscale Network for Target Recognition in Complex-Valued SAR Image with Electromagnetic Feature Fusion. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5217215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Fu, X.; Feng, Y.; Lv, X. Single-Scene SAR Image Data Augmentation Based on SBR and GAN for Target Recognition. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, H.; Cao, Z.; Yang, J. Similarity to Availability: Synthetic Data Assisted SAR Target Recognition via Global Feature Compensation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 770–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Hu, L. SAR Target Recognition Using Only Simulated Data for Training by Hierarchically Combining CNN and Image Similarity. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 4503505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Qiu, X.; Yu, W.; Xu, F. Simulation-assisted SAR Target Classification Based on Unsupervised Domain Adaptation and Model Interpretability Analysis. J. Radars 2022, 11, 168–182. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, X.; Qiu, X.; Yu, W.; Xu, F. Simulation-Aided SAR Target Classification via Dual-Branch Reconstruction and Subdomain Alignment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5214414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Ling, H.; Chou, R. Ray-tube integration in shooting and bouncing ray method. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 1988, 1, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, T.L.; Kajiya, J.T. Ray tracing complex scenes. In Proceedings of the 13th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, New York, NY, USA, 17–19 August 1986; pp. 269–278. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton, J.A.; Chu, L.J. Diffraction Theory of Electromagnetic Waves. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Huang, Y.; Ji, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, P. GF-ResFormer: A Hybrid Gabor-Fourier ResNet-Transformer Network for Precise Semantic Segmentation of High-Resolution Remote Sensing Imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 23779–23800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. CBAM: Convolutional Block Attention Module. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2018, Cham, Switzerland, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, K.; Xiao, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, J. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 5686–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial Pyramid Pooling in Deep Convolutional Networks for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid Scene Parsing Network. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1612.01105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourchid, Y.; Slama, R. MR-STGN: Multi-Residual Spatio Temporal Graph Network Using Attention Fusion for Patient Action Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 25th International Workshop on Multimedia Signal Processing (MMSP), Poitiers, France, 27–29 September 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Ke, X. A Dual-Polarization Information-Guided Network for SAR Ship Classification. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, B.; Huang, L.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, W. OpenSARShip 2.0: A large-volume dataset for deeper interpretation of ship targets in Sentinel-1 imagery. In Proceedings of the 2017 SAR in Big Data Era: Models, Methods and Applications (BIGSARDATA), Beijing, China, 13–14 November 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Ao, W.; Song, Q.; Lai, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, F. FUSAR-Ship: Building a high-resolution SAR-AIS matchup dataset of Gaofen-3 for ship detection and recognition. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2020, 63, 140303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Lu, D.; Qiu, X.; Ding, C. SRSDD-v1.0: A High-Resolution SAR Rotation Ship Detection Dataset. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X.; Ke, X.; Liu, C.; Xu, X.; Zhan, X.; Wang, C.; Ahmad, I.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, D.; et al. HOG-ShipCLSNet: A Novel Deep Learning Network with HOG Feature Fusion for SAR Ship Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5210322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Pu, W.; Wu, C.; Liao, D.; Xu, X.; Wang, C.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yang, J.; et al. HDSS-Net: A Novel Hierarchically Designed Network with Spherical Space Classifier for Ship Recognition in SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5222420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, N.; Zhang, T.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, W. Dual Branch Deep Network for Ship Classification of Dual-Polarized SAR Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5207415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, B.; Li, B.; Guo, W.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, W. OpenSARShip: A Dataset Dedicated to Sentinel-1 Ship Interpretation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Lake Tahoe, NV, USA, 3–8 December 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1801.04381. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50 × fewer parameters and <0.5 MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar]

- Zagoruyko, S.; Komodakis, N. Wide residual networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.07146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X. Squeeze-and-Excitation Laplacian Pyramid Network with Dual-Polarization Feature Fusion for Ship Classification in SAR Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 4019905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, X. A polarization fusion network with geometric feature embedding for SAR ship classification. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 123, 108365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Incident angle | 20∼50 ° | |

| Z-axis rotation angle | 242° | |

| Azimuth scanning angle | 0.7554° | |

| Range resolution | ||

| Azimuth resolution | ||

| Central operating frequency | ||

| Pulse repetition frequency | ||

| Satellite reference slant range | 633,990 m |

| Incident Polarization Form | Horizontal Polarization | Vertical Polarization |

|---|---|---|

| Co-polarization | ||

| Cross-polarization |

| Dataset | Category | # Training | # Validation | # Test | # All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenSARShip | Bulk carrier | 1230 | 352 | 176 | 1758 |

| Container ship | 1395 | 399 | 200 | 1994 | |

| Tanker | 783 | 224 | 113 | 1120 | |

| FUSAR-Ship | Bulk carrier | 171 | 49 | 25 | 245 |

| Container ship | 26 | 8 | 4 | 38 | |

| Tanker | 54 | 16 | 8 | 78 | |

| SRSDD | Bulk carrier | 1437 | 410 | 206 | 2053 |

| Container ship | 62 | 18 | 9 | 89 | |

| Tanker | 116 | 33 | 17 | 166 | |

| BNM (Simulated images) | Bulk carrier | 135 | – | – | 135 |

| Container ship | 135 | – | – | 135 | |

| Tanker | 135 | – | – | 135 |

| Predicted | Bulk Carrier | Container Ship | Tanker | Recall (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||||

| Bulk Carrier | 154 | 16 | 6 | 87.50 | |

| Container ship | 22 | 171 | 7 | 85.50 | |

| Tanker | 12 | 6 | 95 | 84.07 | |

| Precision (%) | 81.91 | 88.60 | 87.96 | Accuracy = 85.89% | |

| F1-Score (%) | 84.62 | 87.02 | 85.97 | ||

| Predicted | Bulk Carrier | Container Ship | Tanker | Recall (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||||

| Bulk Carrier | 165 | 19 | 16 | 82.50 | |

| Container ship | 25 | 168 | 7 | 84.00 | |

| Tanker | 4 | 3 | 193 | 96.50 | |

| Precision (%) | 85.05 | 88.42 | 89.35 | Accuracy = 87.67% | |

| F1-Score (%) | 83.76 | 86.15 | 92.79 | ||

| Predicted | Bulk Carrier | Container Ship | Tanker | Recall (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||||

| Bulk Carrier | 24 | 1 | 0 | 96.00 | |

| Container ship | 1 | 3 | 0 | 75.00 | |

| Tanker | 1 | 0 | 7 | 87.50 | |

| Precision (%) | 92.31 | 75.00 | 100.00 | Accuracy = 91.89% | |

| F1-Score (%) | 94.12 | 75.00 | 93.33 | ||

| Predicted | Bulk Carrier | Container Ship | Tanker | Recall (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||||

| Bulk Carrier | 96 | 3 | 1 | 96.00 | |

| Container ship | 0 | 99 | 1 | 99.00 | |

| Tanker | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100.00 | |

| Precision (%) | 100.00 | 97.06 | 98.04 | Accuracy = 98.33% | |

| F1-Score (%) | 97.96 | 98.02 | 99.01 | ||

| Predicted | Bulk Carrier | Container Ship | Tanker | Recall (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||||

| Bulk Carrier | 203 | 0 | 3 | 98.54 | |

| Container ship | 1 | 8 | 0 | 88.89 | |

| Tanker | 2 | 0 | 15 | 88.24 | |

| Precision (%) | 98.54 | 100.00 | 83.33 | Accuracy = 97.41% | |

| F1-Score (%) | 98.54 | 94.12 | 85.71 | ||

| Predicted | Bulk Carrier | Container Ship | Tanker | Recall (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| True | |||||

| Bulk Carrier | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100.00 | |

| Container ship | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100.00 | |

| Tanker | 3 | 0 | 97 | 97.00 | |

| Precision (%) | 97.09 | 100.00 | 100.00 | Accuracy = 99.00% | |

| F1-Score (%) | 98.52 | 100.00 | 98.48 | ||

| Model | OpenSARShip | FUSAR-Ship | SRSDD | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | |

| AlexNet [49] | 82.42 | 82.41 | 82.35 | 82.41 | 82.68 | 75.68 | 78.41 | 75.68 | 95.38 | 95.26 | 95.31 | 95.26 |

| VGG-16 [50] | 82.12 | 82.00 | 81.97 | 82.00 | 88.89 | 89.19 | 88.73 | 89.19 | 95.94 | 95.69 | 95.76 | 95.69 |

| GoogleNet [51] | 83.52 | 83.44 | 83.43 | 83.44 | 81.98 | 78.38 | 79.61 | 78.38 | 96.36 | 96.12 | 96.19 | 96.12 |

| MobileNet-v2 [52] | 80.71 | 80.37 | 80.35 | 80.37 | 84.94 | 86.49 | 84.98 | 86.49 | 95.52 | 94.83 | 95.03 | 94.83 |

| SqueezeNet-v1.0 [53] | 82.50 | 82.41 | 82.37 | 82.41 | 85.00 | 86.49 | 85.65 | 86.49 | 95.96 | 95.26 | 95.45 | 95.26 |

| Wide-ResNet-50 [54] | 84.54 | 84.46 | 84.45 | 84.46 | 80.54 | 78.38 | 79.34 | 78.38 | 97.06 | 96.98 | 96.99 | 96.98 |

| SE-LPN-DPFF [55] | 76.45 | 78.83 | 77.62 | 79.25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| PFGFE-Net [56] | 80.23 | 79.88 | 78.00 | 79.84 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| DPIG-Net [41] | 85.02 | 82.88 | 83.93 | 81.28 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| HOG-ShipCLSNet [45] | 72.42 | 77.87 | 75.04 | 78.18 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| HDSS-Net [46] | 81.16 | 80.66 | 80.91 | 83.23 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| DBDN [47] | 87.31 | 86.32 | 86.74 | 87.62 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SeDSG (Ours)1 | 86.05 | 85.89 | 85.91 | 85.89 | 92.10 | 91.89 | 91.88 | 91.89 | 97.49 | 97.41 | 97.43 | 97.41 |

| (87.61) | (87.67) | (87.57) | (87.67) | (98.37) | (98.33) | (98.33) | (98.33) | (99.03) | (99.00) | (99.00) | (99.00) | |

| Dataset | Single-Branch(ResNet50+CBAM) | Dual-Branch(SeDSG) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | |

| OpenSARShip | 84.89 | 84.66 | 84.70 | 84.66 | 86.05 | 85.89 | 85.91 | 85.89 |

| OpenSARShip Enhanced | 86.01 | 86.00 | 85.84 | 86.00 | 87.61 | 87.67 | 87.57 | 87.67 |

| FUSAR-Ship | 84.94 | 86.49 | 84.98 | 86.49 | 92.10 | 91.89 | 91.88 | 91.89 |

| FUSAR-Ship Enhanced | 97.74 | 97.67 | 97.67 | 97.67 | 98.37 | 98.33 | 98.33 | 98.33 |

| Pretrain Dataset | SRSDD | SRSDD Enhanced | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | |

| OpenSARShip | 96.45 | 96.55 | 96.45 | 96.55 | 97.72 | 97.67 | 97.67 | 97.67 |

| OpenSARShip Enhanced | 96.29 | 96.12 | 96.19 | 96.12 | 98.69 | 98.67 | 98.67 | 98.67 |

| FUSAR-Ship | 97.16 | 96.98 | 97.02 | 96.98 | 99.01 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 |

| FUSAR-Ship Enhanced | 96.07 | 96.12 | 96.09 | 96.12 | 98.38 | 98.33 | 98.33 | 98.33 |

| No pretrain (epoch = 20) | 95.59 | 95.69 | 95.59 | 95.69 | 98.04 | 98.00 | 98.00 | 98.00 |

| No pretrain (epoch = 50) | 97.49 | 97.41 | 97.43 | 97.41 | 99.03 | 99.00 | 99.00 | 99.00 |

| Model Variant | OpenSARShip | FUSAR-Ship | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBAM | PPNet | Fusion Attention | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) | P (%) | R (%) | F1 (%) | Acc (%) |

| √ | √ | 84.84 | 84.66 | 84.66 | 84.66 | 81.04 | 81.08 | 80.97 | 81.08 | |

| √ | √ | 85.38 | 85.07 | 85.06 | 85.07 | 87.68 | 86.49 | 86.62 | 86.49 | |

| √ | √ | 83.18 | 83.03 | 83.05 | 83.03 | 90.27 | 89.19 | 89.55 | 89.19 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 86.05 | 85.89 | 85.91 | 85.89 | 92.10 | 91.89 | 91.88 | 91.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Feng, Y.; Fu, X.; Feng, S.; Lv, X.; Wang, Y. Electromagnetic Scattering Characteristic-Enhanced Dual-Branch Network with Simulated Image Guidance for SAR Ship Classification. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020252

Feng Y, Fu X, Feng S, Lv X, Wang Y. Electromagnetic Scattering Characteristic-Enhanced Dual-Branch Network with Simulated Image Guidance for SAR Ship Classification. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020252

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Yanlin, Xikai Fu, Shangchen Feng, Xiaolei Lv, and Yiyi Wang. 2026. "Electromagnetic Scattering Characteristic-Enhanced Dual-Branch Network with Simulated Image Guidance for SAR Ship Classification" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020252

APA StyleFeng, Y., Fu, X., Feng, S., Lv, X., & Wang, Y. (2026). Electromagnetic Scattering Characteristic-Enhanced Dual-Branch Network with Simulated Image Guidance for SAR Ship Classification. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020252