High-Frequency Monitoring of Explosion Parameters and Vent Morphology During Stromboli’s May 2021 Crater-Collapse Activity Using UAS and Thermal Imagery

Highlights

- Before the May 2021 collapse at Stromboli, explosions intensified in frequency, spattering, bomb- and gas-rich events, and number of active vents (including gas-dominated explosions, puffing and spattering).

- Post-collapse vent realignment reflected magma adaptation to lithostatic load and magma level drop.

- Monitoring multiple eruption parameters, not just explosion frequency, improves early detection of vent instability.

- High-resolution morphological surveys enhance hazard assessment and risk mitigation at Stromboli and similar volcanoes.

Abstract

1. Introduction

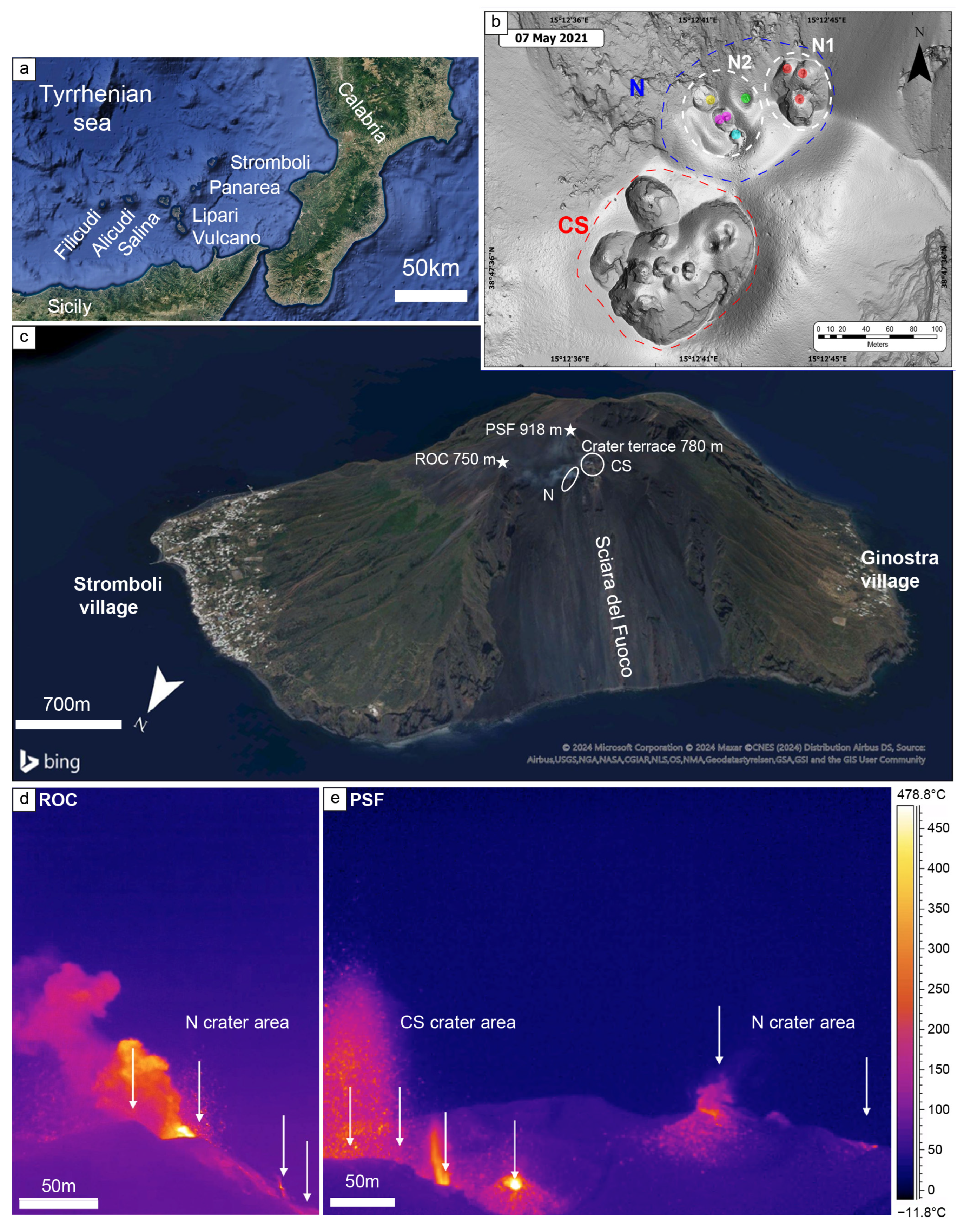

2. Stromboli Volcano

3. Methods

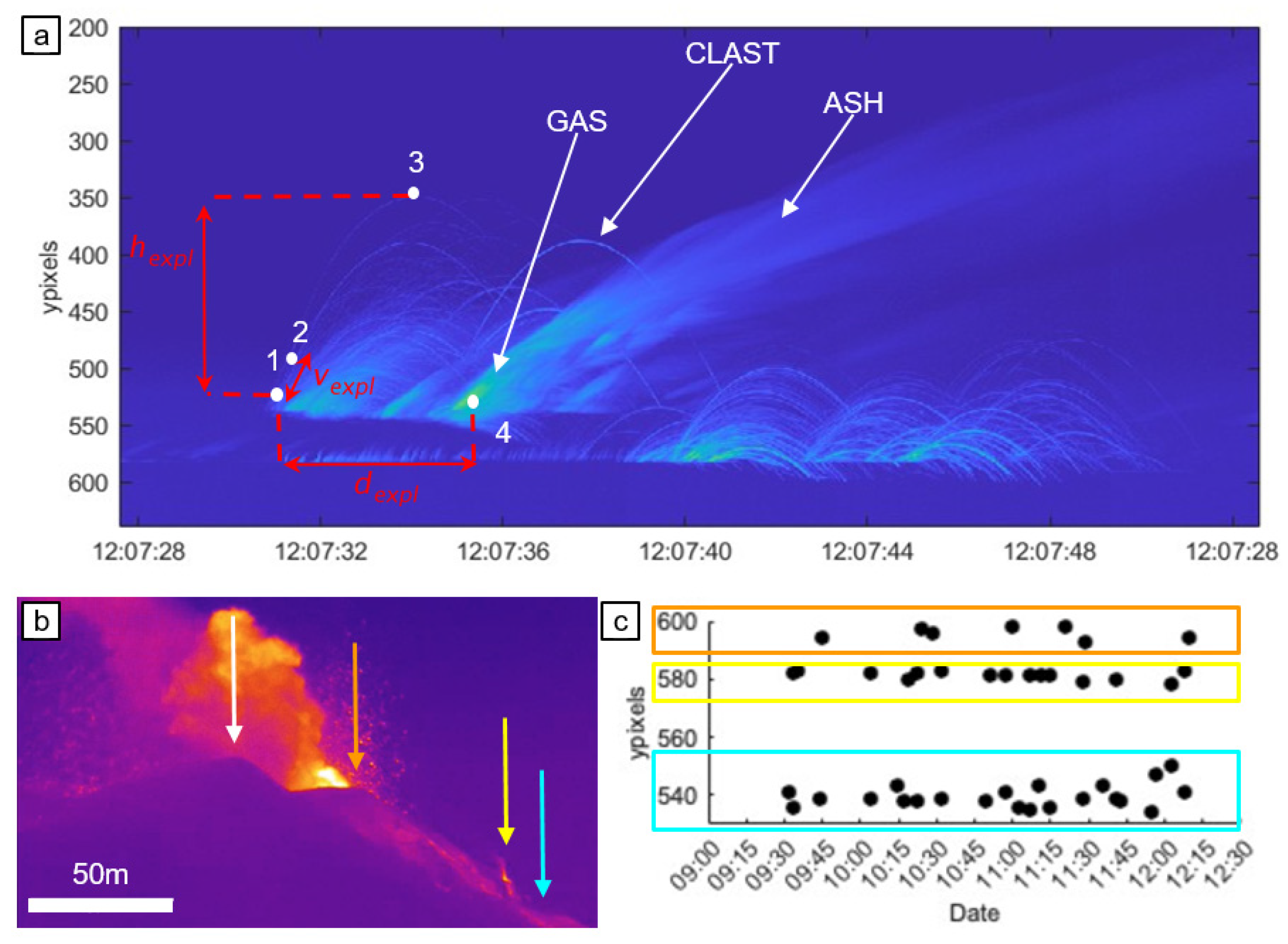

3.1. Thermal Analysis of Explosive Activity with FLIR Camera

- (1)

- Explosion duration (seconds):

- (2)

- Maximum elevation (in meters) of the incandescent pyroclasts/gas thrust region:

- (3)

- Approximate maximum speed of the incandescent pyroclasts/gas thrust region measured close to the vent:

- (4)

- Explosion frequency for each manually picked explosion was calculated as the inverse of the inter-event time dt, the time between two consecutive explosions at the same area or vent:

3.2. UAS-Derived Morphological Analysis

4. Overview of Volcanic Activity in April–May 2021

5. Results

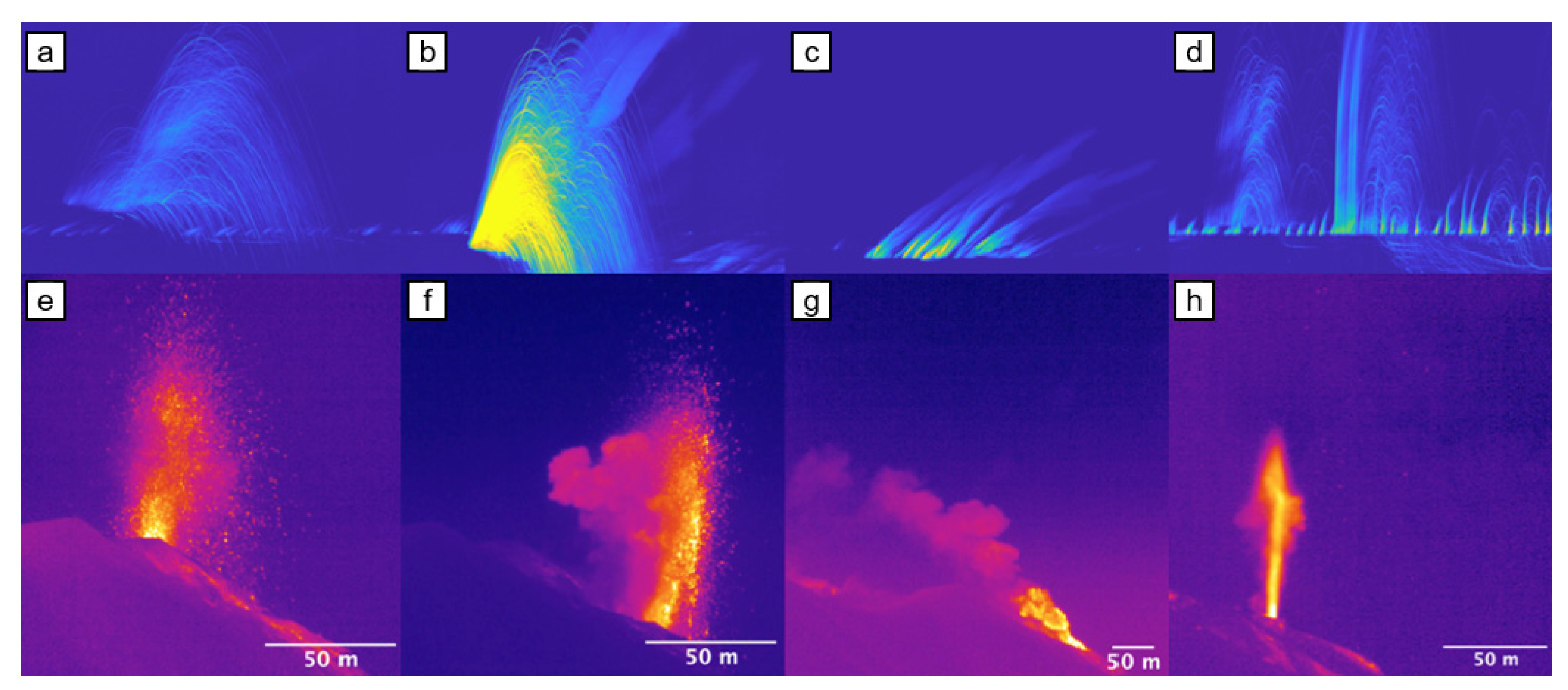

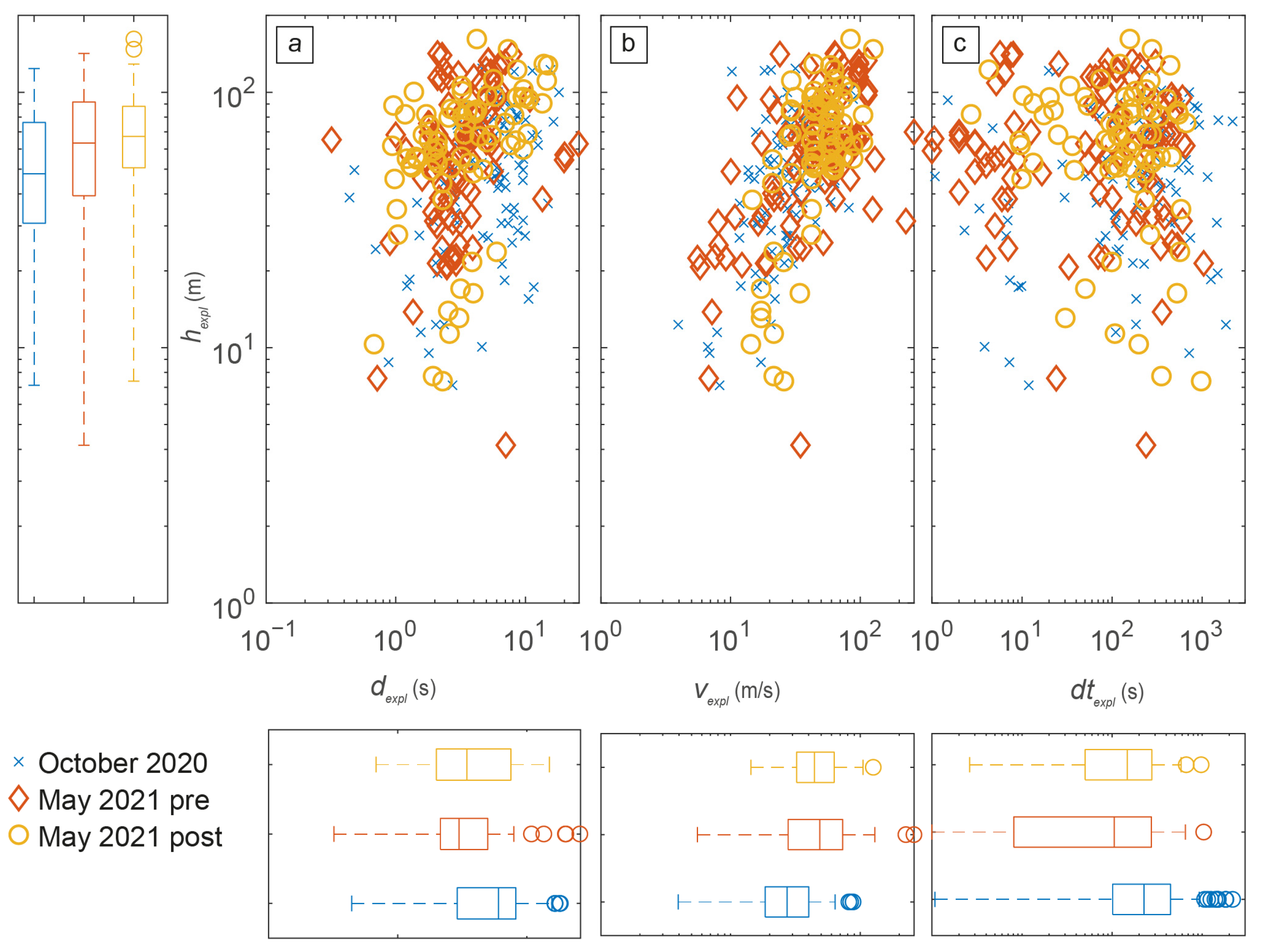

5.1. Temporal and Spatial Changes in Explosion Parameters

5.1.1. Explosion Parameters Pre- and Post- Collapse

5.1.2. Daily Variation of Explosion Parameters

5.2. Morphological Changes and Explosion Parameters in the N Crater Area

5.2.1. Vent-Specific Variations in N Crater Area

5.2.2. Topographic Impact of the May 19 Collapse on the N Crater Area

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Explosion Parameters

6.2. Explosion Types

6.3. N Crater: Branched Conduit Dynamics and Activity Pattern

6.4. Vent Reconfiguration and Structural Modification Induced by the N Crater Area Collapse

6.5. Future Challenges

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simons, B.C.; Jolly, A.D.; Eccles, J.D.; Cronin, S.J. Spatiotemporal Relationships between Two Closely-spaced Strombolian-style Vents, Yasur, Vanuatu. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL085687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, V.; Silleni, A.; Corneli, D.; Taddeucci, J.; Palladino, D.M.; Sottili, G.; Bernini, D.; Andronico, D.; Cristaldi, A. Parameterizing Multi-Vent Activity at Stromboli Volcano (Aeolian Islands, Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 2018, 80, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, L.; Taddeucci, J.; Cannata, A.; Sciotto, M.; Del Bello, E.; Scarlato, P.; Kueppers, U.; Andronico, D.; Privitera, E.; Ricci, T.; et al. Time-Series Analysis of Fissure-Fed Multi-Vent Activity: A Snapshot from the July 2014 Eruption of Etna Volcano (Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 2017, 79, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, L.; Del Bello, E.; Ricci, T.; Taddeucci, J.; Scarlato, P. Multi-Parametric Characterization of Explosive Activity at Batu Tara Volcano (Flores Sea, Indonesia). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2021, 413, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, B.F.; Taddeucci, J.; Andronico, D.; Gonnermann, H.M.; Pistolesi, M.; Patrick, M.R.; Orr, T.R.; Swanson, D.A.; Edmonds, M.; Gaudin, D.; et al. Stronger or Longer: Discriminating between Hawaiian and Strombolian Eruption Styles. Geology 2016, 44, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeucci, J.; Palladino, D.M.; Sottili, G.; Bernini, D.; Andronico, D.; Cristaldi, A. Linked Frequency and Intensity of Persistent Volcanic Activity at Stromboli (Italy). Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3384–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripepe, M.; Rossi, M.; Saccorotti, G. Image Processing of Explosive Activity at Stromboli. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 1993, 54, 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripepe, M.; Delle Donne, D.; Harris, A.; Marchetti, E.; Ulivieri, G. Dynamics of Strombolian Activity. In The Stromboli Volcano: An Integrated Study of the 2002–2003 Eruption; Calvari, S., Inguaggiato, S., Puglisi, G., Ripepe, M., Rosi, M., Eds.; Geophysical Monograph Series; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 182, pp. 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberi, F.; Rosi, M.; Sodi, A. Volcanic hazard assessment at Stromboli based on review of historical data. Acta Vulcanol. 1993, 3, 173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Di Traglia, F.; Bartolini, S.; Artesi, E.; Nolesini, T.; Ciampalini, A.; Lagomarsino, D.; Martí, J.; Casagli, N. Susceptibility of Intrusion-Related Landslides at Volcanic Islands: The Stromboli Case Study. Landslides 2018, 15, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Fornaciai, A.; Casalbore, D.; Favalli, M.; Manzella, I.; Romagnoli, C.; Chiocci, F.L.; Cole, P.; Nolesini, T.; Casagli, N. Subaerial-Submarine Morphological Changes at Stromboli Volcano (Italy) Induced by the 2019–2020 Eruptive Activity. Geomorphology 2022, 400, 108093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccarello, L.; Gheri, D.; De Angelis, S.; Civico, R.; Ricci, T.; Scarlato, P. Geophysical Fingerprint of the 4–11 July 2024 Eruptive Activity at Stromboli Volcano, Italy. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 2317–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvari, S.; Intrieri, E.; Di Traglia, F.; Bonaccorso, A.; Casagli, N.; Cristaldi, A. Monitoring Crater-Wall Collapse at Active Volcanoes: A Study of the 12 January 2013 Event at Stromboli. Bull. Volcanol. 2016, 78, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Borselli, L.; Nolesini, T.; Casagli, N. Crater-Rim Collapse at Stromboli Volcano: Understanding the Mechanisms Leading from the Failure of Hot Rocks to the Development of Glowing Avalanches. Nat. Hazards 2023, 115, 2051–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civico, R.; Ricci, T.; Scarlato, P.; Andronico, D.; Cantarero, M.; Carr, B.B.; De Beni, E.; Del Bello, E.; Johnson, J.B.; Kueppers, U.; et al. Unoccupied Aircraft Systems (UASs) Reveal the Morphological Changes at Stromboli Volcano (Italy) before, between, and after the 3 July and 28 August 2019 Paroxysmal Eruptions. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibaldi, A.; Corazzato, C.; Apuani, T.; Pasquaré, F.A.; Vezzoli, L. Geological-Structural Framework of Stromboli Volcano, Past Collapses, and the Possible Influence on the Events of the 2002–2003 Crisis. In The Stromboli Volcano: An Integrated Study of the 2002–2003 Eruption; Calvari, S., Inguaggiato, S., Puglisi, G., Ripepe, M., Rosi, M., Eds.; Geophysical Monograph Series; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 182, pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, C.; Kokelaar, P.; Casalbore, D.; Chiocci, F.L. Lateral Collapses and Active Sedimentary Processes on the Northwestern Flank of Stromboli Volcano, Italy. Mar. Geol. 2009, 265, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Berardino, P.; Borselli, L.; Calabria, P.; Calvari, S.; Casalbore, D.; Casagli, N.; Casu, F.; Chiocci, F.L.; Civico, R.; et al. Generation of Deposit-Derived Pyroclastic Density Currents by Repeated Crater Rim Failures at Stromboli Volcano (Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 2024, 86, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalbore, D.; Di Traglia, F.; Romagnoli, C.; Favalli, M.; Gracchi, T.; Tacconi Stefanelli, C.; Nolesini, T.; Rossi, G.; Del Soldato, M.; Manzella, I.; et al. Integration of Remote Sensing and Offshore Geophysical Data for Monitoring the Short-Term Morphological Evolution of an Active Volcanic Flank: A Case Study from Stromboli Island. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civico, R.; Ricci, T.; Cecili, A.; Scarlato, P. High-Resolution Topography Reveals Morphological Changes of Stromboli Volcano Following the July 2024 Eruption. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripepe, M.; Lacanna, G. Volcano Generated Tsunami Recorded in the near Source. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, M.R. Dynamics of Strombolian Ash Plumes from Thermal Video: Motion, Morphology, and Air Entrainment. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2007, 112, B06202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, D.; Taddeucci, J.; Scarlato, P.; Harris, A.; Bombrun, M.; Del Bello, E.; Ricci, T. Characteristics of Puffing Activity Revealed by Ground-Based, Thermal Infrared Imaging: The Example of Stromboli Volcano (Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 2017, 79, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombrun, M.; Harris, A.; Gurioli, L.; Battaglia, J.; Barra, V. Anatomy of a Strombolian Eruption: Inferences from Particle Data Recorded with Thermal Video. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2015, 120, 2367–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thivet, S.; Harris, A.J.L.; Gurioli, L.; Bani, P.; Barnie, T.; Bombrun, M.; Marchetti, E. Multi-Parametric Field Experiment Links Explosive Activity and Persistent Degassing at Stromboli. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 669661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Houghton, B.; Taddeucci, J.; von der Lieth, J.; Kueppers, U.; Gaudin, D.; Ricci, T.; Kim, K.; Scarlato, P. Drone Peers into Open Volcanic Vents. Eos 2017, 98, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Kueppers, U.; Civico, R.; Ricci, T.; Taddeucci, J.; Dingwell, D.B. Characterising Vent and Crater Shape Changes at Stromboli: Implications for Risk Areas. Volcanica 2021, 4, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracchi, T.; Tacconi Stefanelli, C.; Rossi, G.; Di Traglia, F.; Nolesini, T.; Tanteri, L.; Casagli, N. UAV-Based Multitemporal Remote Sensing Surveys of Volcano Unstable Flanks: A Case Study from Stromboli. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Ripepe, M. Synergy of Multiple Geophysical Approaches to Unravel Explosive Eruption Conduit and Source Dynamics—A Case Study from Stromboli. Geochemistry 2007, 67, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosi, M.; Pistolesi, M.; Bertagnini, A.; Landi, P.; Pompilio, M.; Di Roberto, A. Chapter 14 Stromboli Volcano, Aeolian Islands (Italy): Present Eruptive Activity and Hazards. Geol. Soc. Lond. Mem. 2013, 37, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CME. INGV Stromboli Weekly Bulletins. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Rosi, M.; Bertagnini, A.; Landi, P. Onset of the Persistent Activity at Stromboli Volcano (Italy). Bull. Volcanol. 2000, 62, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.; Ripepe, M. Temperature and Dynamics of Degassing at Stromboli. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2007, 112, B03205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colò, L.; Ripepe, M.; Baker, D.R.; Polacci, M. Magma Vesiculation and Infrasonic Activity at Stromboli Open Conduit Volcano. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 292, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, D.; Taddeucci, J.; Scarlato, P.; del Bello, E.; Ricci, T.; Orr, T.; Houghton, B.; Harris, A.; Rao, S.; Bucci, A. Integrating Puffing and Explosions in a General Scheme for Strombolian-style Activity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 1860–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, M.R.; Harris, A.J.L.; Ripepe, M.; Dehn, J.; Rothery, D.A.; Calvari, S. Strombolian Explosive Styles and Source Conditions: Insights from Thermal (FLIR) Video. Bull. Volcanol. 2007, 69, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvari, S.; Spampinato, L.; Lodato, L.; Harris, A.J.L.; Patrick, M.R.; Dehn, J.; Burton, M.R.; Andronico, D. Chronology and Complex Volcanic Processes during the 2002–2003 Flank Eruption at Stromboli Volcano (Italy) Reconstructed from Direct Observations and Surveys with a Handheld Thermal Camera. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2005, 110, B02201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valade, S.; Lacanna, G.; Coppola, D.; Laiolo, M.; Pistolesi, M.; Donne, D.D.; Genco, R.; Marchetti, E.; Ulivieri, G.; Allocca, C.; et al. Tracking Dynamics of Magma Migration in Open-Conduit Systems. Bull. Volcanol. 2016, 78, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevilacqua, A.; Bertagnini, A.; Pompilio, M.; Landi, P.; Del Carlo, P.; Di Roberto, A.; Aspinall, W.; Neri, A. Major Explosions and Paroxysms at Stromboli (Italy): A New Historical Catalog and Temporal Models of Occurrence with Uncertainty Quantification. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeucci, J.; Scarlato, P.; Del Bello, E.; Tamburello, G.; Gaudin, D. Eruptions from UV to TIR: Multispectral High-Speed Imaging of Explosive Volcanic Activity. In Light, Energy and the Environment 2018 (E2, FTS, HISE, SOLAR, SSL); OSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; p. HM2C.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.J.L.; Delle Donne, D.; Dehn, J.; Ripepe, M.; Worden, A.K. Volcanic Plume and Bomb Field Masses from Thermal Infrared Camera Imagery. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 365, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.; Allard, P.; Muré, F.; La Spina, A. Magmatic Gas Composition Reveals the Source Depth of Slug-Driven Strombolian Explosive Activity. Science (1979) 2007, 317, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaupart, C.; Vergniolle, S. Laboratory Models of Hawaiian and Strombolian Eruptions. Nature 1988, 331, 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, P.; Carbonnelle, J.; Métrich, N.; Loyer, H.; Zettwoog, P. Sulphur Output and Magma Degassing Budget of Stromboli Volcano. Nature 1994, 368, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, P.; Aiuppa, A.; Burton, M.; Caltabiano, T.; Federico, C.; Salerno, G.; La Spina, A. Crater Gas Emissions and the Magma Feeding System of Stromboli Volcano. In The Stromboli Volcano: An Integrated Study of the 2002–2003 Eruption; Calvari, S., Inguaggiato, S., Puglisi, G., Ripepe, M., Rosi, M., Eds.; Geophysical Monograph Series; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 182, pp. 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiuppa, A.; Bertagnini, A.; Métrich, N.; Moretti, R.; Di Muro, A.; Liuzzo, M.; Tamburello, G. A Model of Degassing for Stromboli Volcano. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 295, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leduc, L.; Gurioli, L.; Harris, A.; Colò, L.; Rose-Koga, E.F. Types and Mechanisms of Strombolian Explosions: Characterization of a Gas-Dominated Explosion at Stromboli. Bull. Volcanol. 2015, 77, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, A.; Ripepe, M.; Lacanna, G. Wideband Acoustic Records of Explosive Volcanic Eruptions at Stromboli: New Insights on the Explosive Process and the Acoustic Source. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 3851–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maramai, A.; Graziani, L.; Alessio, G.; Burrato, P.; Colini, L.; Cucci, L.; Nappi, R.; Nardi, A.; Vilardo, G. Near- and Far-Field Survey Report of the 30 December 2002 Stromboli (Southern Italy) Tsunami. Mar. Geol. 2005, 215, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinti, S.; Maramai, A.; Armigliato, A.; Graziani, L.; Manucci, A.; Pagnoni, G.; Zaniboni, F. Observations of Physical Effects from Tsunamis of December 30, 2002 at Stromboli Volcano, Southern Italy. Bull. Volcanol. 2006, 68, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, M.R.; Robson, S. Straightforward Reconstruction of 3D Surfaces and Topography with a Camera: Accuracy and Geoscience Application. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2012, 117, F03017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geomorphic Change Detection Software. Available online: https://gcd.riverscapes.net/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- CME. UNIFI LGS Stromboli Weekly Bulletins. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/categoria-1 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 12/04/2021–18/04/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/668-bollettinostromboli20210420/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- LGS_UNIFI. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report. 06/05/2021–13/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/categoria-1/683-70-bollettino-unifi-lgs-stromboli-20210513/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 26/04/2021–02/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/675-bollettinostromboli20210504/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 03/05/2021–09/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/682-bollettinostromboli20210511/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 10/05/2021–16/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/684-bollettinostromboli20210518/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 17/05/2021–23/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/720-bollettinostromboli20210525/filehttps://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/720-bollettinostromboli20210525/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- LGS_UNIFI. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report. 13/05/2021–20/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/categoria-1/691-71-bollettino-unifi-lgs-stromboli-20210520/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 24/05/2021–30/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/730-bollettinostromboli20210601/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 31/05/2021–06/06/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/736-bollettinostromboli20210608/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- LGS_UNIFI. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report. 21/05/2021–27/05/2021. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/categoria-1/717-72-bollettino-unifi-lgs-stromboli-20210527/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 05/10/2020–11/10/2020. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/512-bollettinostromboli20201013/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- LGS. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report. 08/10/2020–15/10/2020. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/categoria-1/490-41-bollettino-settimanale-dell-attivita-del-vulcano-stromboli-08-ottobre-15-ottobre-2020/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Calvari, S.; Di Traglia, F.; Ganci, G.; Bruno, V.; Ciancitto, F.; Di Lieto, B.; Gambino, S.; Garcia, A.; Giudicepietro, F.; Inguaggiato, S.; et al. Multi-Parametric Study of an Eruptive Phase Comprising Unrest, Major Explosions, Crater Failure, Pyroclastic Density Currents and Lava Flows: Stromboli Volcano, 1 December 2020–30 June 2021. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 899635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delle Donne, D.; Tamburello, G.; Aiuppa, A.; Bitetto, M.; Lacanna, G.; D’Aleo, R.; Ripepe, M. Exploring the Explosive-effusive Transition Using Permanent Ultraviolet Cameras. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2017, 122, 4377–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INGV. Weekly Volcanic Activity Report: 30/03/2020–05/04/2020. Available online: https://cme.ingv.it/bollettini-e-comunicati/bollettini-ingv-stromboli/32-bollettinostromboli20200407/file (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Ripepe, M.; Delle Donne, D.; Lacanna, G.; Marchetti, E.; Ulivieri, G. The Onset of the 2007 Stromboli Effusive Eruption Recorded by an Integrated Geophysical Network. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2009, 182, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvari, S.; Lodato, L.; Steffke, A.; Cristaldi, A.; Harris, A.J.L.; Spampinato, L.; Boschi, E. The 2007 Stromboli Eruption: Event Chronology and Effusion Rates Using Thermal Infrared Data. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2010, 115, B04201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Traglia, F.; Calvari, S.; D’Auria, L.; Nolesini, T.; Bonaccorso, A.; Fornaciai, A.; Esposito, A.; Cristaldi, A.; Favalli, M.; Casagli, N. The 2014 Effusive Eruption at Stromboli: New Insights from In Situ and Remote-Sensing Measurements. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronico, D.; Del Bello, E.; D’Oriano, C.; Landi, P.; Pardini, F.; Scarlato, P.; de’ Michieli Vitturi, M.; Taddeucci, J.; Cristaldi, A.; Ciancitto, F.; et al. Uncovering the Eruptive Patterns of the 2019 Double Paroxysm Eruption Crisis of Stromboli Volcano. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landi, P.; Marchetti, E.; La Felice, S.; Ripepe, M.; Rosi, M. Integrated Petrochemical and Geophysical Data Reveals Thermal Distribution of the Feeding Conduits at Stromboli Volcano, Italy. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L08305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurioli, L.; Colo’, L.; Bollasina, A.J.; Harris, A.J.L.; Whittington, A.; Ripepe, M. Dynamics of Strombolian Explosions: Inferences from Field and Laboratory Studies of Erupted Bombs from Stromboli Volcano. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2014, 119, 319–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bello, E.; Lane, S.J.; James, M.R.; Llewellin, E.W.; Taddeucci, J.; Scarlato, P.; Capponi, A. Viscous Plugging Can Enhance and Modulate Explosivity of Strombolian Eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2015, 423, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capponi, A.; James, M.R.; Lane, S.J. Gas Slug Ascent in a Stratified Magma: Implications of Flow Organisation and Instability for Strombolian Eruption Dynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2016, 435, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvari, S.; Pinkerton, H. Birth, Growth and Morphologic Evolution of the ‘Laghetto’ Cinder Cone during the 2001 Etna Eruption. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2004, 132, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiuppa, A.; Bitetto, M.; Delle Donne, D.; La Monica, F.P.; Tamburello, G.; Coppola, D.; Della Schiava, M.; Innocenti, L.; Lacanna, G.; Laiolo, M.; et al. Volcanic CO2 Tracks the Incubation Period of Basaltic Paroxysms. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabh0191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudicepietro, F.; Calvari, S.; D’Auria, L.; Di Traglia, F.; Layer, L.; Macedonio, G.; Caputo, T.; De Cesare, W.; Ganci, G.; Martini, M.; et al. Changes in the Eruptive Style of Stromboli Volcano before the 2019 Paroxysmal Phase Discovered through SOM Clustering of Seismo-Acoustic Features Compared with Camera Images and GBInSAR Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontesilli, A.; Del Bello, E.; Scarlato, P.; Mollo, S.; Ellis, B.; Andronico, D.; Taddeucci, J.; Nazzari, M. The Efficacy of High Frequency Petrological Investigation at Open-Conduit Volcanoes: The Case of May 11 2019 Explosions at Southwestern and Northeastern Craters of Stromboli. Lithos 2023, 454–455, 107255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, G.; De Astis, G. The Summer 2019 Basaltic Vulcanian Eruptions (Paroxysms) of Stromboli. Bull. Volcanol. 2021, 83, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripepe, M.; Harris, A.J.L.; Marchetti, E. Coupled Thermal Oscillations in Explosive Activity at Different Craters of Stromboli Volcano. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L17302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripepe, M.; Delle Donne, D.; Legrand, D.; Valade, S.; Lacanna, G. Magma Pressure Discharge Induces Very Long Period Seismicity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimura, S.; Nishimura, T.; Lacanna, G.; Legrand, D.; Valade, S.; Ripepe, M. Seismic Source Migration During Strombolian Eruptions Inferred by Very-Near-Field Broadband Seismic Network. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2021, 126, e2021JB022623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouet, B.; Dawson, P.; Martini, M. Shallow-Conduit Dynamics at Stromboli Volcano, Italy, Imaged from Waveform Inversions. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2008, 307, 57–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioli, L.; Calvari, S.; Inguaggiato, S.; Puglisi, G.; Ripepe, M.; Rosi, M. The eruptive activity of 28 and 29 December 2002. In The Stromboli Volcano: An Integrated Study of the 2002–2003 Eruption; Calvari, S., Inguaggiato, S., Puglisi, G., Ripepe, M., Rosi, M., Eds.; Geophysical Monograph Series; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume 182, pp. 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Calvari, S.; Di Traglia, F.; Ganci, G.; Giudicepietro, F.; Macedonio, G.; Cappello, A.; Nolesini, T.; Pecora, E.; Bilotta, G.; Centorrino, V.; et al. Overflows and Pyroclastic Density Currents in March-April 2020 at Stromboli Volcano Detected by Remote Sensing and Seismic Monitoring Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, V.; Neri, M.; Scarlato, P. Understanding Shallow Magma Emplacement at Volcanoes: Orthogonal Feeder Dikes during the 2002–2003 Stromboli (Italy) Eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L17310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, T.; Walter, T.R.; Müller, D.; Guðmundsson, M.T.; Schöpa, A. The Relationship Between Lava Fountaining and Vent Morphology for the 2014–2015 Holuhraun Eruption, Iceland, Analyzed by Video Monitoring and Topographic Mapping. Front. Earth Sci. 2018, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, E.; Calvari, S.; Cristaldi, A.; D’Auria, L.; Di Vito, M.A.; Moretti, R.; Peluso, R.; Spampinato, L.; Boschi, E. Reactivation of Stromboli’s Summit Craters at the End of the 2007 Effusive Eruption Detected by Thermal Surveys and Seismicity. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2015, 120, 7376–7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvari, S.; Nunnari, G. Statistical Insights on the Eruptive Activity at Stromboli Volcano (Italy) Recorded from 1879 to 2023. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, V.; Ripepe, M.; Rivalta, E.; Peltier, A.; Galetto, F.; Joseph, E. Towards Scientific Forecasting of Magmatic Eruptions. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 5, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stix, J.; de Moor, J.M.; Aiuppa, A. Understanding and Forecasting Sudden Explosive Eruptions. Bull. Volcanol. 2025, 87, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudicepietro, F.; López, C.; Macedonio, G.; Alparone, S.; Bianco, F.; Calvari, S.; De Cesare, W.; Delle Donne, D.; Di Lieto, B.; Esposito, A.M.; et al. Geophysical Precursors of the July-August 2019 Paroxysmal Eruptive Phase and Their Implications for Stromboli Volcano (Italy) Monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Day | Time (ti–tf) | OP | Cam. Setup (SD/f/θ/psize) | Max. Error | VFOV (m) | Fr (Hz) | No. Expl. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08/10/2020 | 13:06:07–14:03:28 | ROC | 387/13/0/0.5 | <2% | 323.9 | 50 | 11 |

| 09/10/2020 (1) | 09:25:46–12:21:22 | ROC | 387/24/0/0.3 | <2% | 175.4 | 50 | 44 |

| 09/10/2020 (2) | 12:23:40–13:15:46 | ROC | 387/41/0/0.2 | <2% | 102.7 | 50 | 10 |

| 09/10/2020 (3) | 13:19:40–14:15:10 | ROC | 387/41/0/0.2 | <2% | 102.7 | 50 | 9 |

| 10/10/2020 | 10:02:55–13:46:04 | ROC | 387/41/0/0.2 | <2% | 102.7 | 50 | 17 |

| 11/10/2020 | 08:55:38–11:31:17 | ROC | 387/41/0/0.2 | <2% | 102.4 | 50 | 22 |

| 10/05/2021 | 10:04:59–12:36:03 | PSF | 248|302/13/20/0.3|0.4 | <7% | 165.7|201.7 | 25 | 44 |

| 13/05/2021 | 09:46:51–10:41:00 | ROC | 417/41/0/0.2 | <2% | 83.0 | 50 | 10 |

| 16/05/2021 | 08:56:32–10:37:31 | PSF | 248|302/13/20/0.3|0.4 | <7% | 165.7|201.7 | 50 | 46 |

| 25/05/2021 | 17:40:30–18:32:18 | ROC | 415/41/0/0.2 | <2% | 82.6 | 50 | 11 |

| 26/05/2021 (1) | 08:33:42–11:22:11 | ROC | 415/24/0/0.3 | <2% | 188.1 | 50 | 40 |

| 26/05/2021 (2) | 12:13:54–13:24:32 | PSF | 248|302/13/20/0.4|0.4 | <7% | 165.7|201.7 | 50 | 29 |

| Date | UAS | No. DSM Images (Total) | Flight Path | DSMs Res. (cm/pix) | Orto Res. (cm/pix) | Camera Location Tot. Error (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 May 2021 | 1 */2/3 | 1064 (3013) | Predefined | 11.3 | 10 | 1.5 |

| 8 May 2021 | 1 */2/3 | 847 (1120) | Predefined | 10.9 | 10 | 1.2 |

| 9 May 2021 | 2 */3 | 95 (311) | Manual | 4.8 | 10 | 110 |

| 10 May 2021 | 2/3 * | 103 (103) | Manual | 5.1 | 10 | 94 |

| 26 May 2021 | 3 *,° | 269 (1017) | Manual | 11.2 | 10 | 910 |

| 27 May 2021 | 3 *,° | 74 (192) | Manual |

| Date | Explosion Types | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2a | 2b | 0 | ||

| 08/10/2020 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 11 |

| 09/10/2020 | 24 | 30 | 9 | 0 | 63 |

| 10/10/2020 | 0 | 13 | 4 | 0 | 17 |

| 11/10/2020 | 14 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 22 |

| Total October | 45 (40%) | 46 (41%) | 22 (19%) | 0 (0%) | 113 |

| 10/05/2021 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 44 |

| 13/05/2021 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 10 |

| 16/05/2021 | 28 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 46 |

| Total pre | 69 (69%) | 18 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (13%) | 100 |

| 26/05/2021 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 26/05/2021 | 35 | 29 | 5 | 0 | 69 |

| Total post | 36 (45%) | 39 (49%) | 5 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 80 |

| Total May | 105 (58%) | 57 (32%) | 5 (3%) | 13 (7%) | 180 |

| Total | 150 (51%) | 103 (35%) | 27 (9%) | 13 (5%) | 293 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Del Bello, E.; Zanella, G.; Civico, R.; Ricci, T.; Taddeucci, J.; Andronico, D.; Cristaldi, A.; Scarlato, P. High-Frequency Monitoring of Explosion Parameters and Vent Morphology During Stromboli’s May 2021 Crater-Collapse Activity Using UAS and Thermal Imagery. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020264

Del Bello E, Zanella G, Civico R, Ricci T, Taddeucci J, Andronico D, Cristaldi A, Scarlato P. High-Frequency Monitoring of Explosion Parameters and Vent Morphology During Stromboli’s May 2021 Crater-Collapse Activity Using UAS and Thermal Imagery. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):264. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020264

Chicago/Turabian StyleDel Bello, Elisabetta, Gaia Zanella, Riccardo Civico, Tullio Ricci, Jacopo Taddeucci, Daniele Andronico, Antonio Cristaldi, and Piergiorgio Scarlato. 2026. "High-Frequency Monitoring of Explosion Parameters and Vent Morphology During Stromboli’s May 2021 Crater-Collapse Activity Using UAS and Thermal Imagery" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020264

APA StyleDel Bello, E., Zanella, G., Civico, R., Ricci, T., Taddeucci, J., Andronico, D., Cristaldi, A., & Scarlato, P. (2026). High-Frequency Monitoring of Explosion Parameters and Vent Morphology During Stromboli’s May 2021 Crater-Collapse Activity Using UAS and Thermal Imagery. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020264