CFFCNet: Center-Guided Feature Fusion Completion for Accurate Vehicle Localization and Dimension Estimation from Lidar Point Clouds

Highlights

- CFFCNet achieves substantial improvements in vehicle localization and dimension estimation from incomplete lidar point clouds, reducing localization MAE to 0.0928 m and length MAE to 0.085 m on the KITTI dataset.

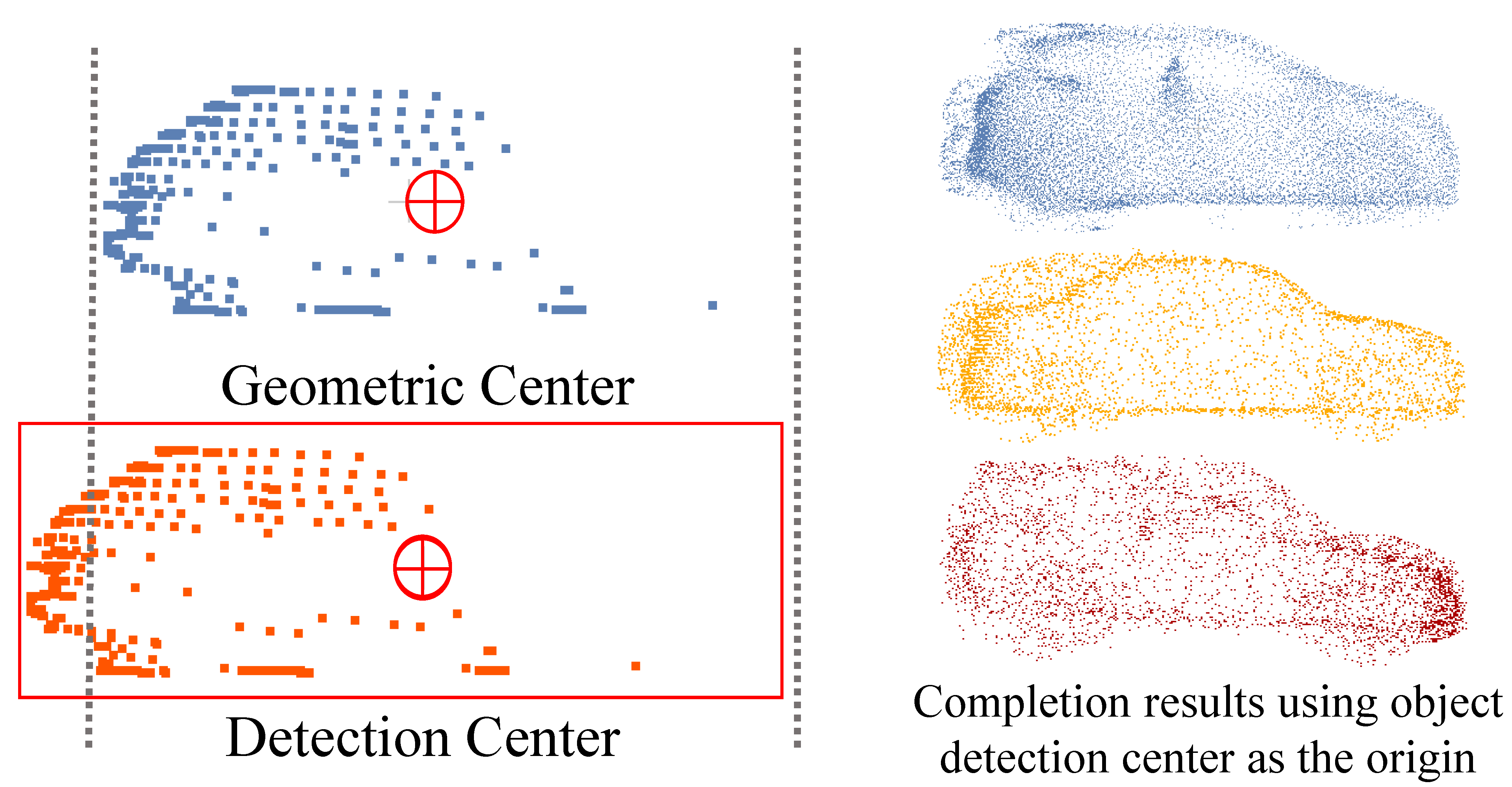

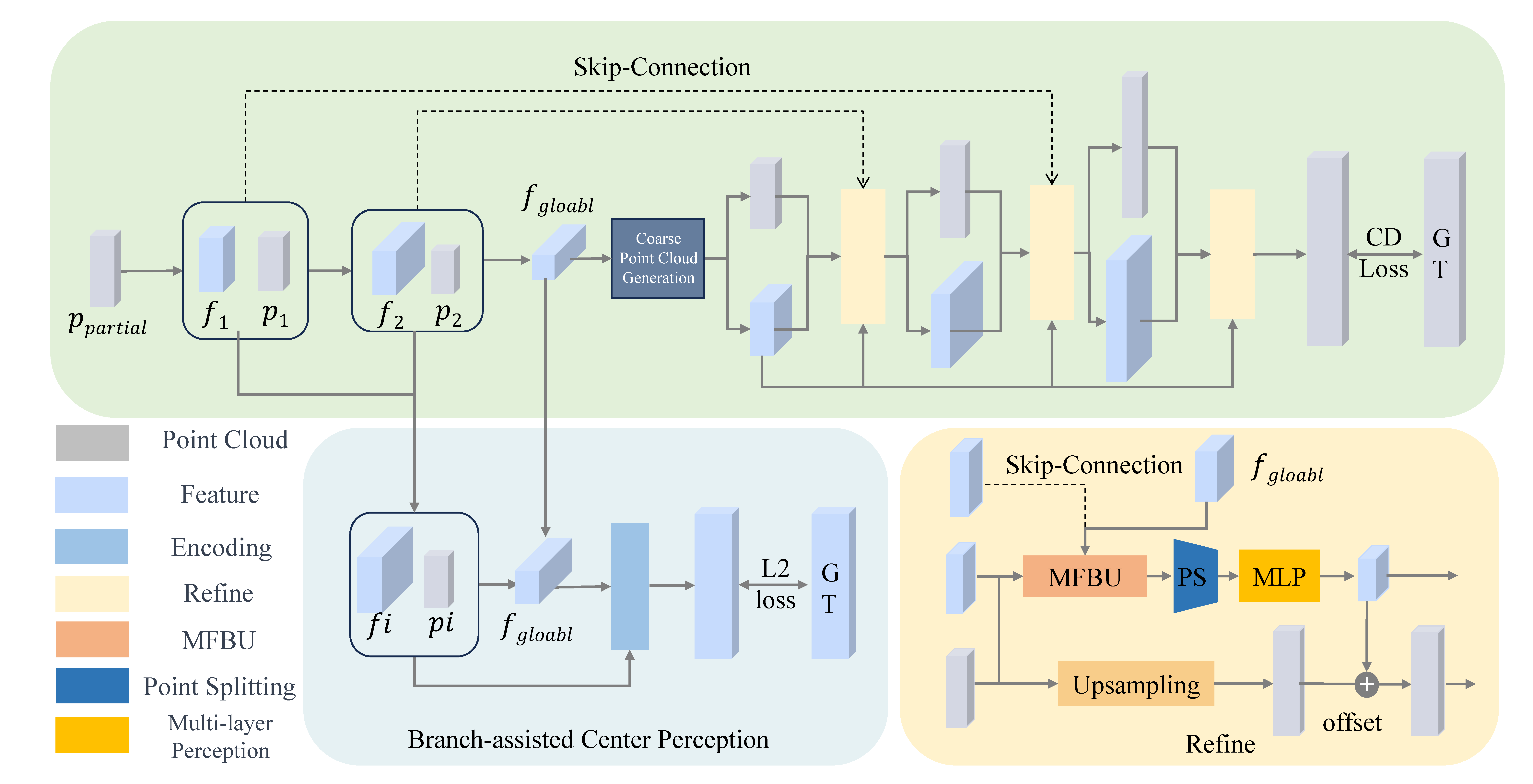

- The proposed Branch-assisted Center Perception (BCP) module effectively addresses the misalignment between detection centers and true geometric centers in real-world scenarios, while the Multi-scale Feature Blending Upsampling (MFBU) module enhances geometric reconstruction through hierarchical feature fusion.

- The method demonstrates strong generalization capability from vehicle-mounted to roadside lidar data without fine-tuning, achieving localization MAE of 0.051 m on the CUG-Roadside dataset, enabling practical deployment in infrastructure-based traffic monitoring systems.

- Center-guided point cloud completion provides a new paradigm for precise 3D perception in intelligent transportation systems, contributing to safer autonomous navigation and more accurate traffic flow analysis in urban environments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose CFFCNet, a novel geometry-aware shape completion network explicitly designed to enhance vehicle localization and dimension estimation. By integrating center guidance into the completion process, our method effectively addresses the critical misalignment issue between detection centers and true geometric centers in real-world sparse point clouds.

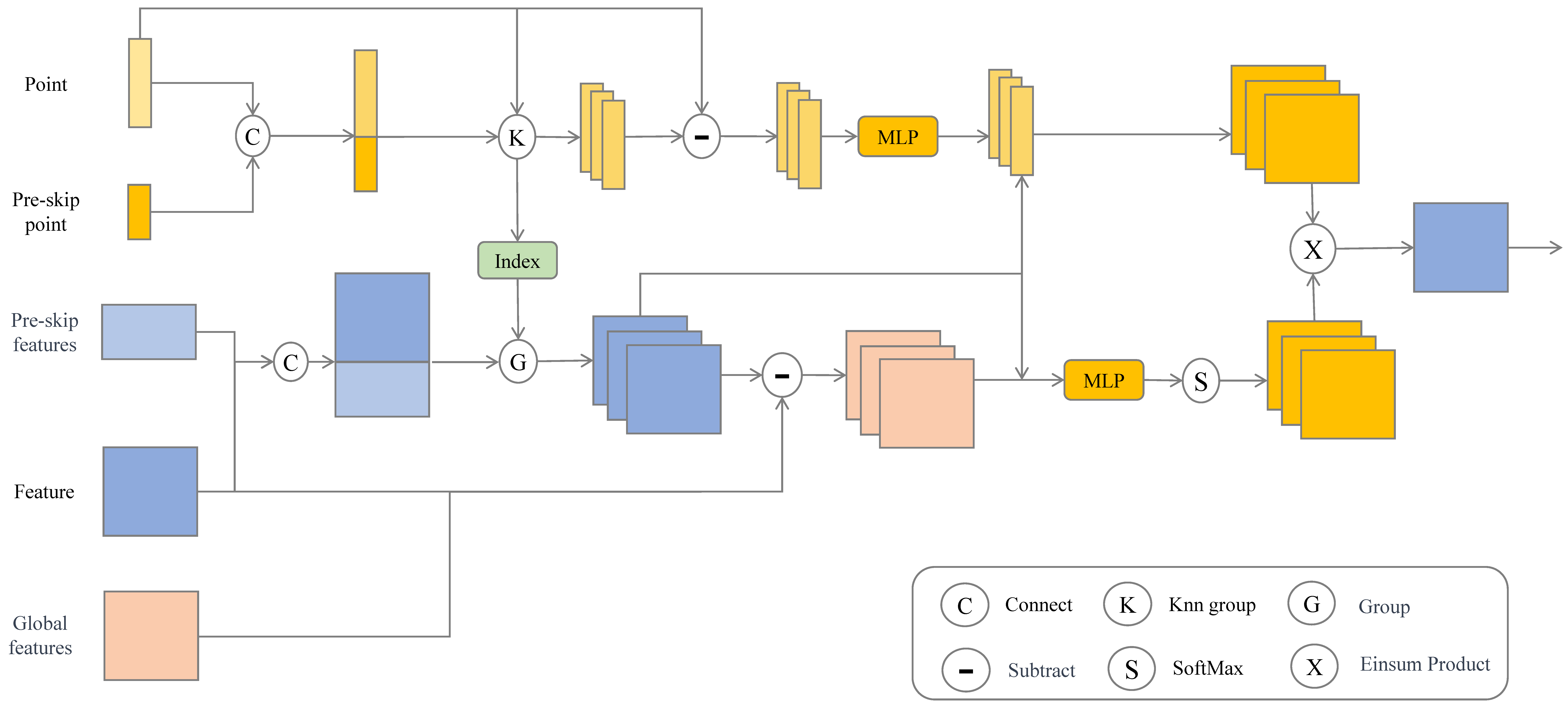

- We introduce a Branch-assisted Center Perception (BCP) module and a Multi-scale Feature Blending Upsampling (MFBU) module. The BCP module provides implicit supervision for accurate center and dimension prediction, while the MFBU module employs a cross-attention mechanism to fuse multi-level local and global features. This combination significantly improves the recovery of fine-grained geometric details and ensures high-fidelity completion.

2. Related Work

2.1. 3D Object Detection

2.2. Point Cloud Completion

3. Method

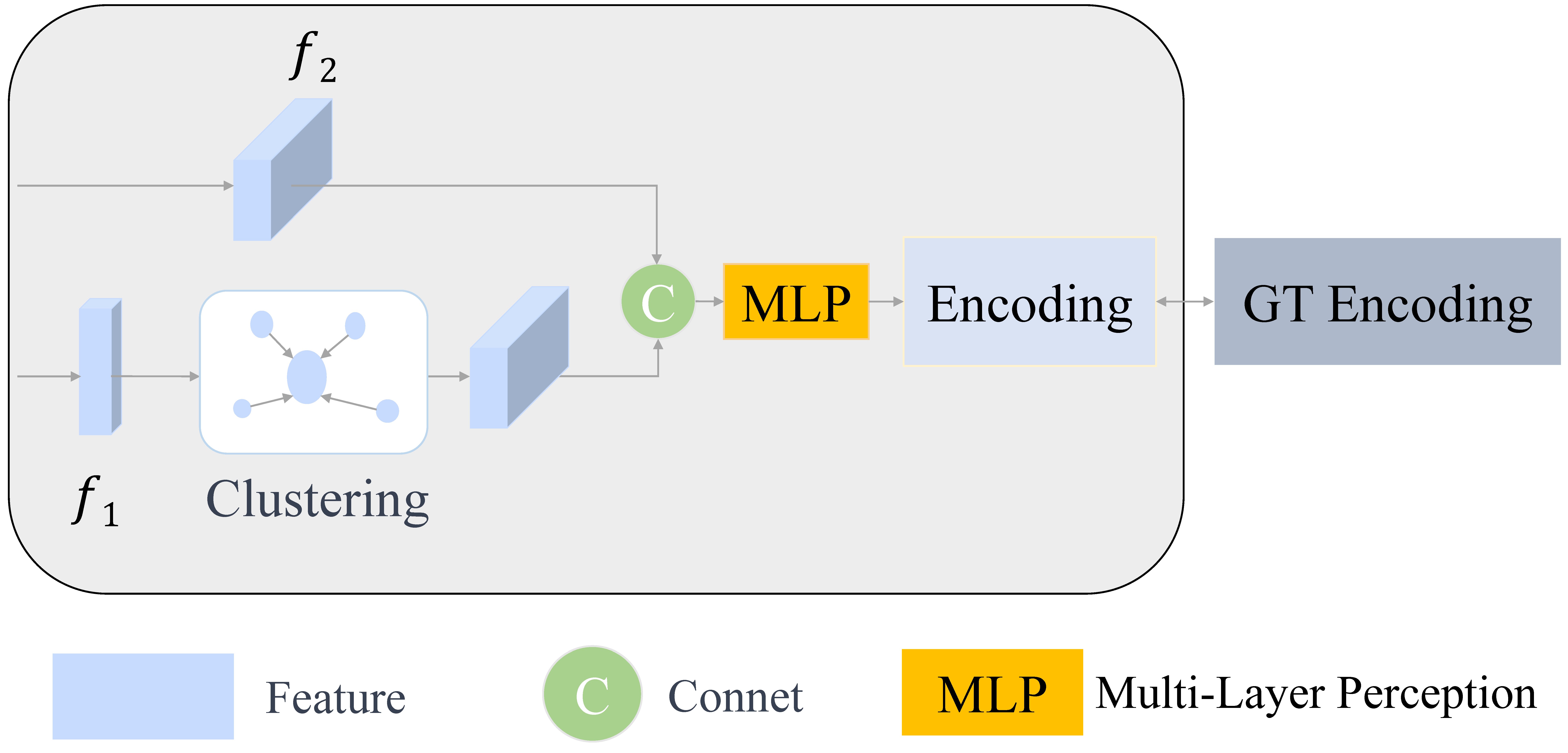

3.1. Branch-Assisted Center Perception (BCP) Module

3.1.1. Branch Feature Extraction

3.1.2. Encoding Loss Regression

3.2. Multi-Scale Feature Blending Upsampling (MFBU) Module

3.3. Multi-Task Loss

4. Experiments

4.1. Dataset

4.1.1. Training Dataset

4.1.2. Test Dataset

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Comparative Experiments

4.4. Ablation Study

4.5. Evaluation Metric

5. Results

5.1. Evaluation on the KITTI Dataset

5.2. Evaluation on the CUG-Roadside Dataset

5.3. Results of Ablation Experiments

5.3.1. Impact of the BCP and MFBU Modules

5.3.2. Impact of Distance on Completion Performance

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| BCP | Branch-assisted Center Perception |

| CFFCNet | Center-guided Feature Fusion Completion Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| GNSSs | Global Navigation Satellite Systems |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MFBU | Multi-scale Feature Blending Upsampling |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| OD | Object Detection |

| RPN | Region Proposal Network |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| ROI | Region of Interest |

| SPDs | Snowflake Point Deconvolutions |

References

- Woo, H.; Kang, E.; Wang, S.; Lee, K.H. A New Segmentation Method for Point Cloud Data. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2002, 42, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.H.; Cai, J.X.; Liu, Z.N.; Mu, T.J.; Martin, R.R.; Hu, S.M. PCT: Point Cloud Transformer. Comput. Vis. Media 2021, 7, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Bennamoun, M. Deep Learning for 3D Point Clouds: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 4338–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.F.; Jin, J.S.; Wang, M.J.; Jiang, W.; Gao, L.; Xiao, L. A Review of Algorithms for Filtering the 3D Point Cloud. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2017, 57, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yao, G.; Liu, L.; Pei, Q.; Song, H.; Dustdar, S. A Cooperative Vehicle-Infrastructure System for Road Hazards Detection With Edge Intelligence. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 5186–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liu, H.; He, J.; Sun, Q.; Du, X. A Graph-Based One-Shot Learning Method for Point Cloud Recognition. In Proceedings of the Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 39, pp. 313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Yurtsever, E.; Lambert, J.; Carballo, A.; Takeda, K. A Survey of Autonomous Driving: Common Practices and Emerging Technologies. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 58443–58469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M.; Ohrhallinger, S.; Wimmer, M. Efficient Collision Detection While Rendering Dynamic Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the Graphics Interface; AK Peters/CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, P.; Cagle, L.; Reza, T.; Ball, J.; Gafford, J. LiDAR and Camera Detection Fusion in a Real-Time Industrial Multi-Sensor Collision Avoidance System. Electronics 2018, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, C.; Lin, L.; Wen, C.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J. Automated Visual Recognizability Evaluation of Traffic Sign Based on 3D LiDAR Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Cheng, X.; Geng, Q.; Cao, B.; Zhou, D.; Wang, P.; Lin, Y.; Yang, R. The ApolloScape Dataset for Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 954–960. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Coifman, B. Using Spatiotemporal Stacks for Precise Vehicle Tracking from Roadside 3D LiDAR Data. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 154, 104280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, W.; Coifman, B.; Mills, J.P. Vehicle Tracking and Speed Estimation From Roadside LiDAR. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 5597–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zeng, H.; Huang, J.; Hua, X.S.; Zhang, L. Structure Aware Single-Stage 3D Object Detection from Point Cloud. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11873–11882. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Tuzel, O. VoxelNet: End-to-End Learning for Point Cloud Based 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4490–4499. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Cai, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Sotelo, M.A.; Li, Z. Voxel-RCNN-Complex: An Effective 3D Point Cloud Object Detector for Complex Traffic Conditions. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, C.; Xia, F.; Leng, Z.; Anguelov, D. SWFormer: Sparse Window Transformer for 3D Object Detection in Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 426–442. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Meng, Z.; Xing, Y.; Ma, Y.; Wattenhofer, R. 3D-RETR: End-to-End Single and Multi-View 3D Reconstruction with Transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.08861. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Dai, G.; Zhou, W.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Z. Multi-Scale Feature Fusion with Attention Mechanism for Crowded Road Object Detection. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2024, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Junnan, C.; Gao, G.; Li, J.; Hu, X. HEDNet: A Hierarchical Encoder-Decoder Network for 3D Object Detection in Point Clouds. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 36, 12345–12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanakos, G.; Tsochatzidis, L.; Amanatiadis, A.; Pratikakis, I. A Comprehensive Survey of LiDAR-Based 3D Object Detection Methods with Deep Learning for Autonomous Driving. Comput. Graph. 2021, 99, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Xu, J.; Ni, F.; Le, X. PF-Net: Point Fractal Network for 3D Point Cloud Completion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 7662–7670. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Du, H.; Chen, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y. YOLO-ACN: Focusing on Small Target and Occluded Object Detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 227288–227303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 652–660. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5105–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ang, M.H., Jr.; Lee, G.H. Cascaded Refinement Network for Point Cloud Completion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 790–799. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, P.; Wen, X.; Liu, Y.S.; Cao, Y.P.; Wan, P.; Zheng, W.; Han, Z. SnowflakeNet: Point Cloud Completion by Snowflake Point Deconvolution with Skip-Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 5499–5509. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.; Chen, H.; Lu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.L.; Wei, M. SPCNet: Stepwise Point Cloud Completion Network. In Proceedings of the Computer Graphics Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; Volume 41, pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Xu, G.; Xu, K.; Wan, J.; Ma, Y. Point Cloud Completion by Dynamic Transformer with Adaptive Neighbourhood Feature Fusion. IET Comput. Vis. 2022, 16, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Shi, P.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, Y.; Shuang, F. Dual Feature Fusion Network: A Dual Feature Fusion Network for Point Cloud Completion. IET Comput. Vis. 2022, 16, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.X.; Funkhouser, T.; Guibas, L.; Hanrahan, P.; Huang, Q.; Li, Z.; Savarese, S.; Savva, M.; Song, S.; Hao, S.; et al. ShapeNet: An Information-Rich 3D Model Repository. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03012. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision Meets Robotics: The KITTI Dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, Y.; Guo, D.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Shen, C. PointAttn: You Only Need Attention for Point Cloud Completion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.08485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H. PointRCNN: 3D Object Proposal Generation and Detection from Point Cloud. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 770–779. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Han, X.; Niethammer, M. VoteNet: A Deep Learning Label Fusion Method for Multi-Atlas Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 202–210. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Jia, J. 3DSSD: Point-Based 3D Single Stage Object Detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11040–11048. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Xia, Z.; Song, S.; Li, L.E.; Huang, G. 3D Object Detection with PointFormer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7463–7472. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, H.; Cai, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, B.; Huang, J.; Hua, X.S.; Zhao, M.J. Improving 3D Object Detection with Channel-Wise Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 2743–2752. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Dai, X.; Xiao, B.; Yuan, L.; Gao, J. Focal Self-Attention for Local-Global Interactions in Vision Transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.00641. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yin, J.; Li, W.; Xu, C.; Yang, R.; Shen, J. Di-V2X: Learning Domain-Invariant Representation for Vehicle-Infrastructure Collaborative 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–30 March 2024; Volume 38, pp. 3208–3215. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y. PC-RGNN: Point Cloud Completion and Graph Neural Network for 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 3430–3437. [Google Scholar]

- Du, L.; Ye, X.; Tan, X.; Feng, J.; Xu, Z.; Ding, E.; Wen, S. Associate-3Ddet: Perceptual-to-Conceptual Association for 3D Point Cloud Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 13329–13338. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yao, Y.; Quan, Z.; Yang, W.; Xie, J. SIENet: Spatial Information Enhancement Network for 3D Object Detection from Point Cloud. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.15396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Neumann, U. Behind the Curtain: Learning Occluded Shapes for 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 22–29 February 2022; Volume 36, pp. 2893–2901. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, W.; Zhao, D.; Premebida, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Tian, D. Improving 3D Vulnerable Road User Detection with Point Augmentation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 2783–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A.; Qi, C.R.; Nießner, M. Shape Completion Using 3D-Encoder-Predictor CNNs and Shape Synthesis. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5868–5877. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, H.; Kalogerakis, E.; Yu, Y. High-Resolution Shape Completion Using Deep Neural Networks for Global Structure and Local Geometry Inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Stutz, D.; Geiger, A. Learning 3D Shape Completion from Laser Scan Data with Weak Supervision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 1955–1964. [Google Scholar]

- Le, T.; Duan, Y. PointGrid: A Deep Network for 3D Shape Understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 9204–9214. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, D.; Scherer, S. VoxNet: A 3D Convolutional Neural Network for Real-Time Object Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 922–928. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Khot, T.; Held, D.; Mertz, C.; Hebert, M. PCN: Point Completion Network. In Proceedings of the International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 10–12 September 2018; pp. 728–737. [Google Scholar]

- Tchapmi, L.P.; Kosaraju, V.; Rezatofighi, H.; Reid, I.; Savarese, S. TopNet: Structural Point Cloud Decoder. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, X.; Li, T.; Han, Z.; Liu, Y.S. Point Cloud Completion by Skip-Attention Network with Hierarchical Folding. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1939–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Feng, C.; Shen, Y.; Tian, D. FoldingNet: Point Cloud Auto-Encoder via Deep Grid Deformation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, L.; Jia, J.; Torr, P.H.S.; Koltun, V. Point Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 16259–16268. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Rao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. PoinTr: Diverse Point Cloud Completion with Geometry-Aware Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 12498–12507. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Rao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. AdaPoinTr: Diverse Point Cloud Completion with Adaptive Geometry-Aware Transformers. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.04545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Xiang, P.; Han, Z.; Cao, Y.P.; Wan, P.; Zheng, W.; Liu, Y.S. PMP-Net++: Point Cloud Completion by Transformer-Enhanced Multi-Step Point Moving Paths. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Scott, D.; Li, X.; Wang, S. Orthogonal Dictionary Guided Shape Completion Network for Point Cloud. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–30 March 2024; Volume 38, pp. 864–872. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Deng, J.; Wen, C.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Li, J. CasA: A Cascade Attention Network for 3D Object Detection From LiDAR Point Clouds. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yao, H.; Zhou, S.; Mao, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, W. GRNet: Gridding Residual Network for Dense Point Cloud Completion. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Virtual Event, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Du, Y.; Wu, J. 3D Shape Generation and Completion Through Point-Voxel Diffusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 5826–5835. [Google Scholar]

- Romanelis, I.; Fotis, V.; Kalogeras, A.; Alexakos, C.; Moustakas, K.; Munteanu, A. Efficient and Scalable Point Cloud Generation with Sparse Point-Voxel Diffusion Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.06145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Length (m) | Width (m) | Height (m) | Center (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original detection | 0.1103 | 0.0444 | 0.1469 | 0.0955 |

| GRNet | 0.2023 | 0.1542 | 0.1931 | 0.1628 |

| SnowflakeNet | 0.1855 | 0.0753 | 0.0911 | 0.1538 |

| AdaPoinTr | 0.1841 | 0.1679 | 0.2653 | 0.0940 |

| ODGNet | 0.1488 | 0.1343 | 0.1211 | 0.1042 |

| CFFCNet (Ours) | 0.0850 | 0.0594 | 0.0750 | 0.0928 |

| Model | Params (M) | FPS (f/s) |

|---|---|---|

| GRNet | 76.70 | 12.31 |

| SnowflakeNet | 19.30 | 16.15 |

| AdaPoinTr | 30.88 | 14.89 |

| ODGNet | 11.41 | 17.38 |

| CFFCNet (Ours) | 20.02 | 14.30 |

| Model | Length (m) | Width (m) | Height (m) | Center (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original detection | 0.134 | 0.243 | 0.053 | 0.084 |

| GRNet | 0.225 | 0.278 | 0.581 | 0.197 |

| SnowflakeNet | 0.216 | 0.205 | 0.431 | 0.175 |

| AdaPoinTr | 0.278 | 0.160 | 0.572 | 0.066 |

| ODGNet | 0.138 | 0.182 | 0.476 | 0.104 |

| CFFCNet (Ours) | 0.051 | 0.259 | 0.303 | 0.051 |

| Model | MFBU | BCP | Length (m) | Width (m) | Height (m) | Center (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFFC-BCP | ✓ | 0.1026 | 0.0744 | 0.0866 | 0.0927 | |

| CFFC-MFBU | ✓ | 0.0920 | 0.0590 | 0.0710 | 0.0938 | |

| CFFCNet | ✓ | ✓ | 0.0850 | 0.0590 | 0.0750 | 0.0928 |

| Range (m) | Num | Orig. Center | Comp. Center | Orig. L | Orig. W | Orig. H | Comp. L | Comp. W | Comp. H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤10 | 438 | 0.146 | 0.149 | 0.129 | 0.048 | 0.140 | 0.096 | 0.057 | 0.072 |

| 10–15 | 466 | 0.090 | 0.088 | 0.114 | 0.040 | 0.142 | 0.089 | 0.052 | 0.045 |

| 15–20 | 454 | 0.080 | 0.074 | 0.115 | 0.044 | 0.145 | 0.089 | 0.065 | 0.062 |

| 20–25 | 436 | 0.079 | 0.073 | 0.101 | 0.043 | 0.146 | 0.077 | 0.062 | 0.076 |

| 25–50 | 464 | 0.084 | 0.082 | 0.093 | 0.047 | 0.161 | 0.072 | 0.062 | 0.120 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Feng, X.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, W.; Tang, M.; Sun, K. CFFCNet: Center-Guided Feature Fusion Completion for Accurate Vehicle Localization and Dimension Estimation from Lidar Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010039

Chen X, Feng X, Zhang S, Xiao W, Tang M, Sun K. CFFCNet: Center-Guided Feature Fusion Completion for Accurate Vehicle Localization and Dimension Estimation from Lidar Point Clouds. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiaoyi, Xiao Feng, Shichen Zhang, Wen Xiao, Miao Tang, and Kun Sun. 2026. "CFFCNet: Center-Guided Feature Fusion Completion for Accurate Vehicle Localization and Dimension Estimation from Lidar Point Clouds" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010039

APA StyleChen, X., Feng, X., Zhang, S., Xiao, W., Tang, M., & Sun, K. (2026). CFFCNet: Center-Guided Feature Fusion Completion for Accurate Vehicle Localization and Dimension Estimation from Lidar Point Clouds. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010039