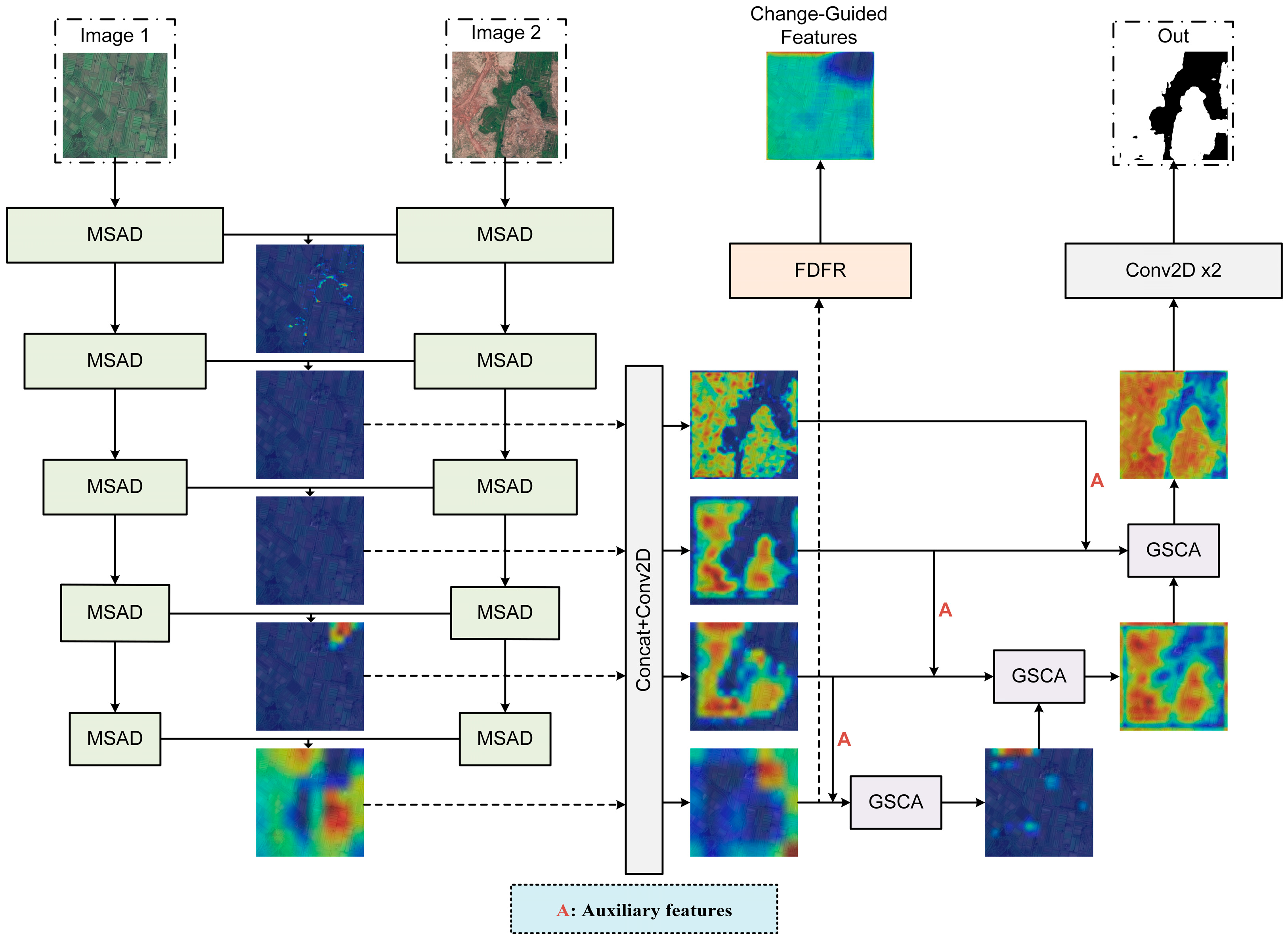

FarmChanger: A Diffusion-Guided Network for Farmland Change Detection

Highlights

- A novel diffusion-guided network, FarmChanger, is proposed to overcome challenges in multi-scale structure modeling, pseudo-change suppression, and fine boundary reconstruction in farmland change detection.

- The integration of three modules—MSAD, FDFR, and GSCA—enables adaptive multi-scale feature extraction, diffusion-inspired feature refinement, and cross-feature spatial guidance, achieving superior accuracy and robustness on benchmark datasets.

- FarmChanger provides an efficient and reliable framework for large-scale and high-frequency farmland monitoring under complex seasonal and illumination variations.

- The proposed diffusion-guided and attention-enhanced mechanisms offer a transferable strategy for designing generalizable models in broader remote sensing change detection applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

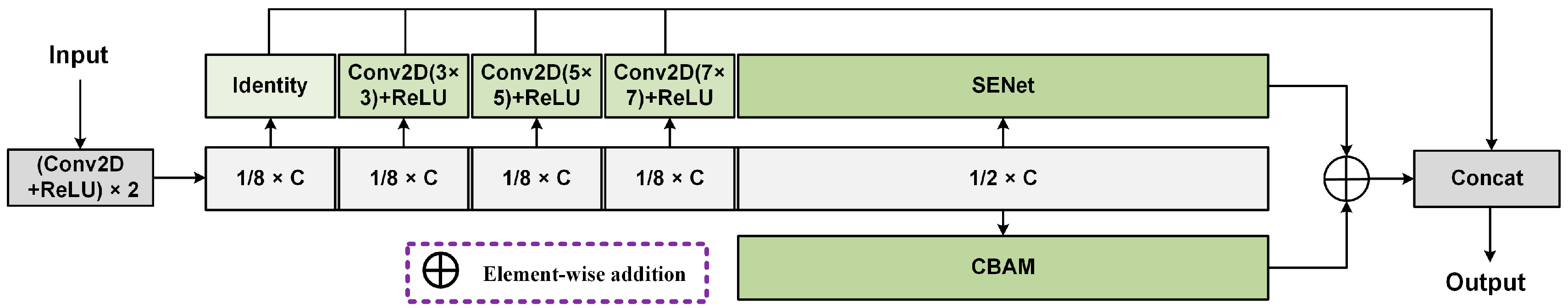

2.1. Multi-Scale Adaptive Downsample (MSAD) Block

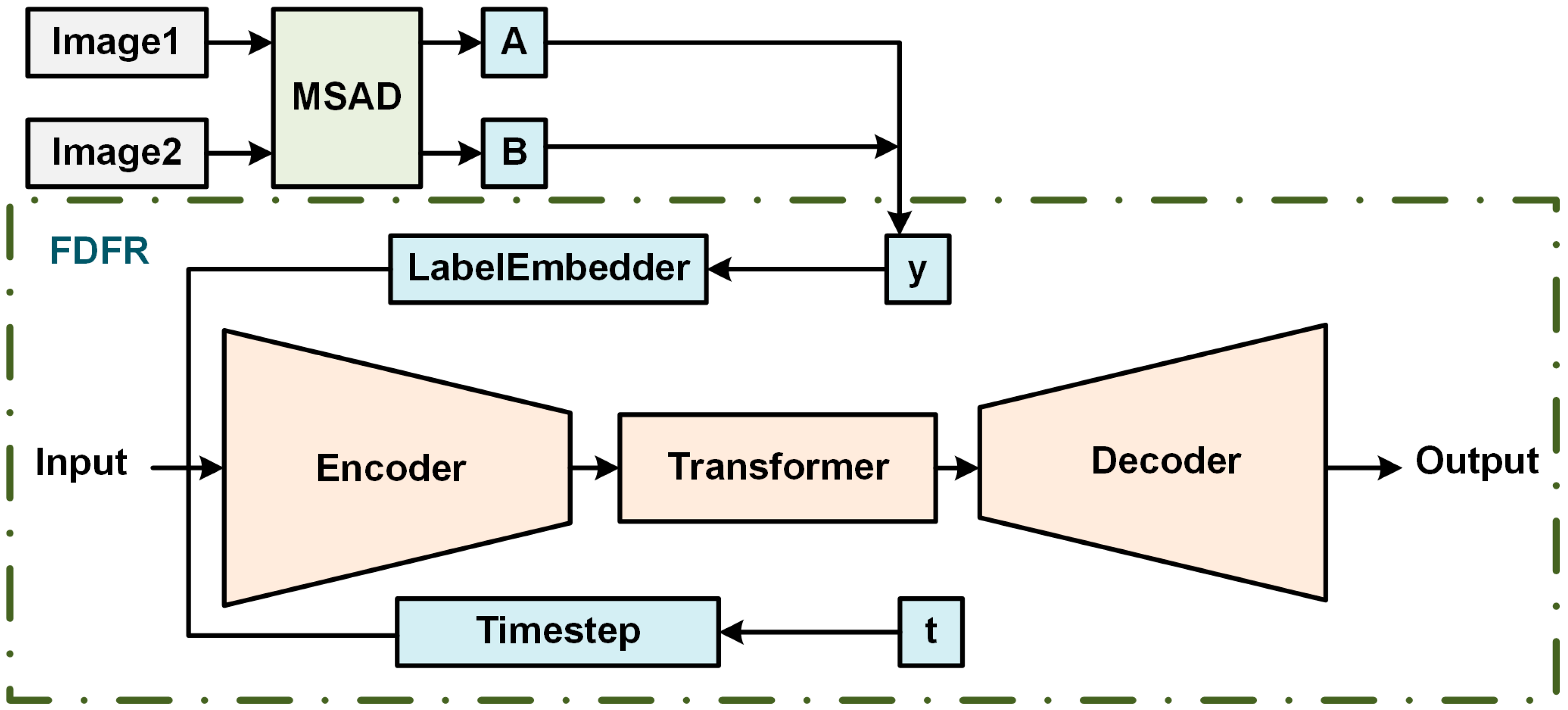

2.2. Field Diffusion-Inspired Feature Refiner (FDFR) Module

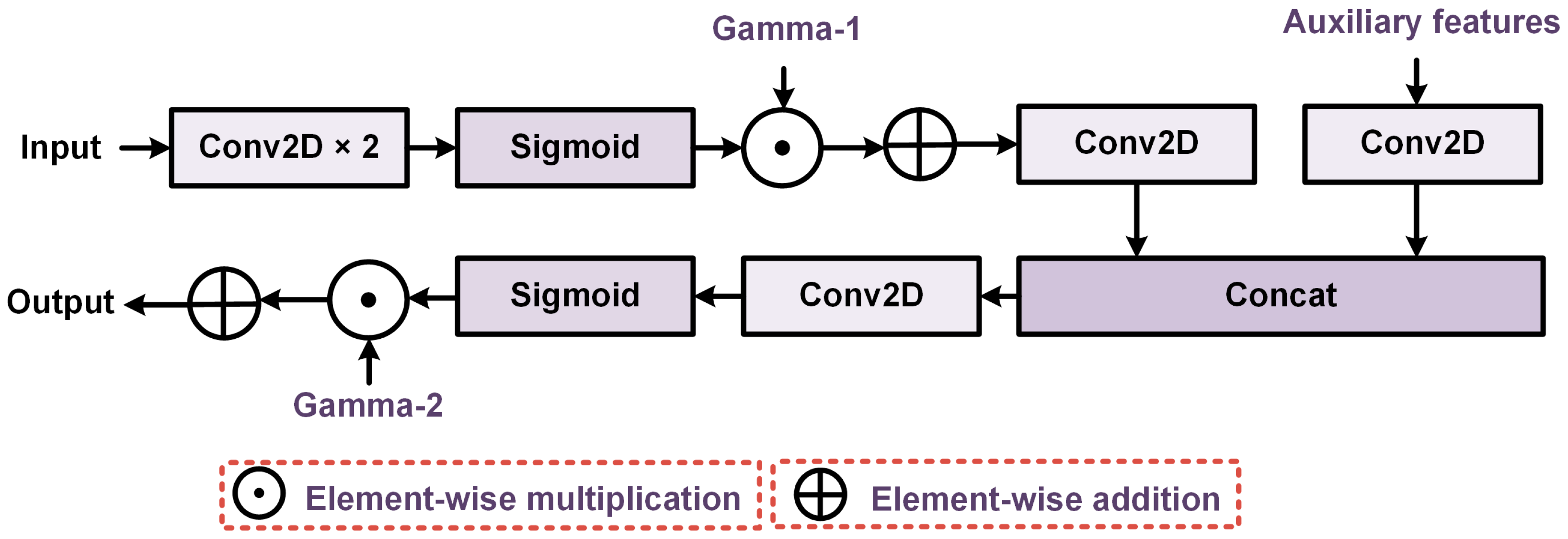

2.3. Guided Spatial-Cross Attention (GSCA) Module

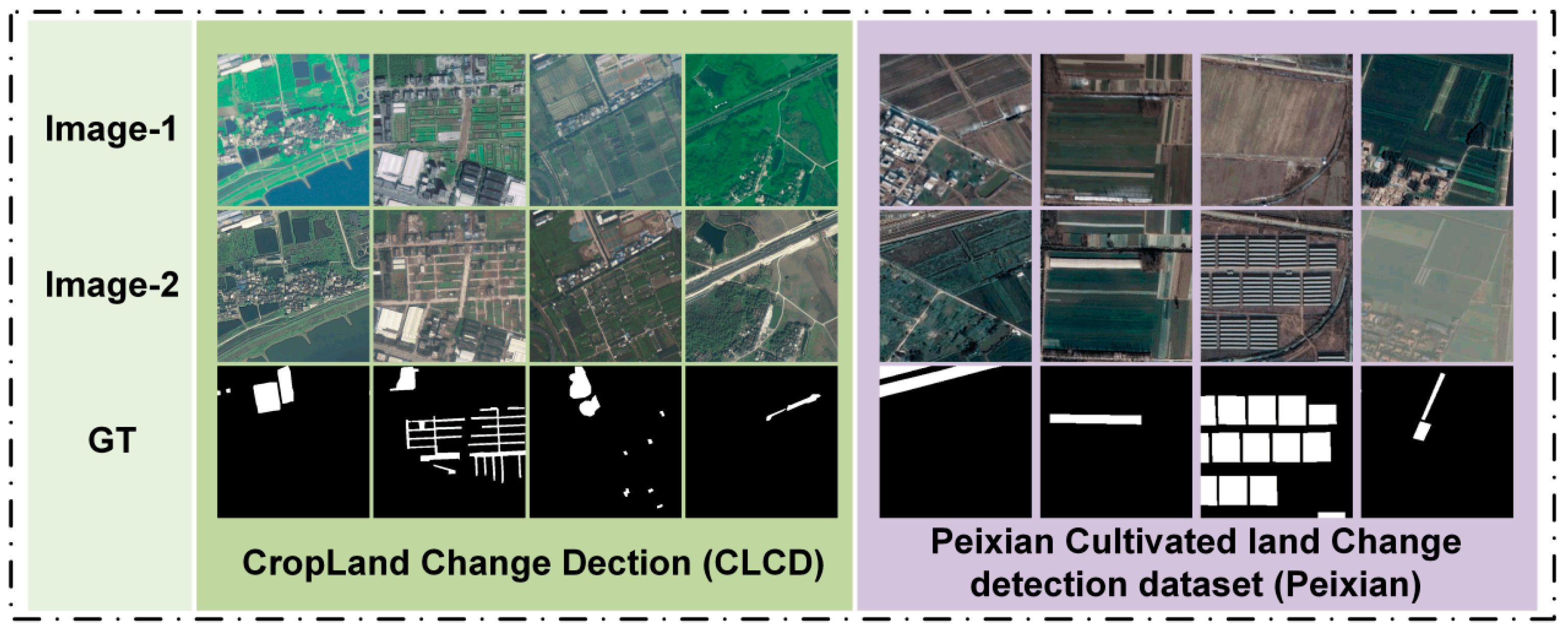

3. Datasets

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Platform and Evaluation Metrics

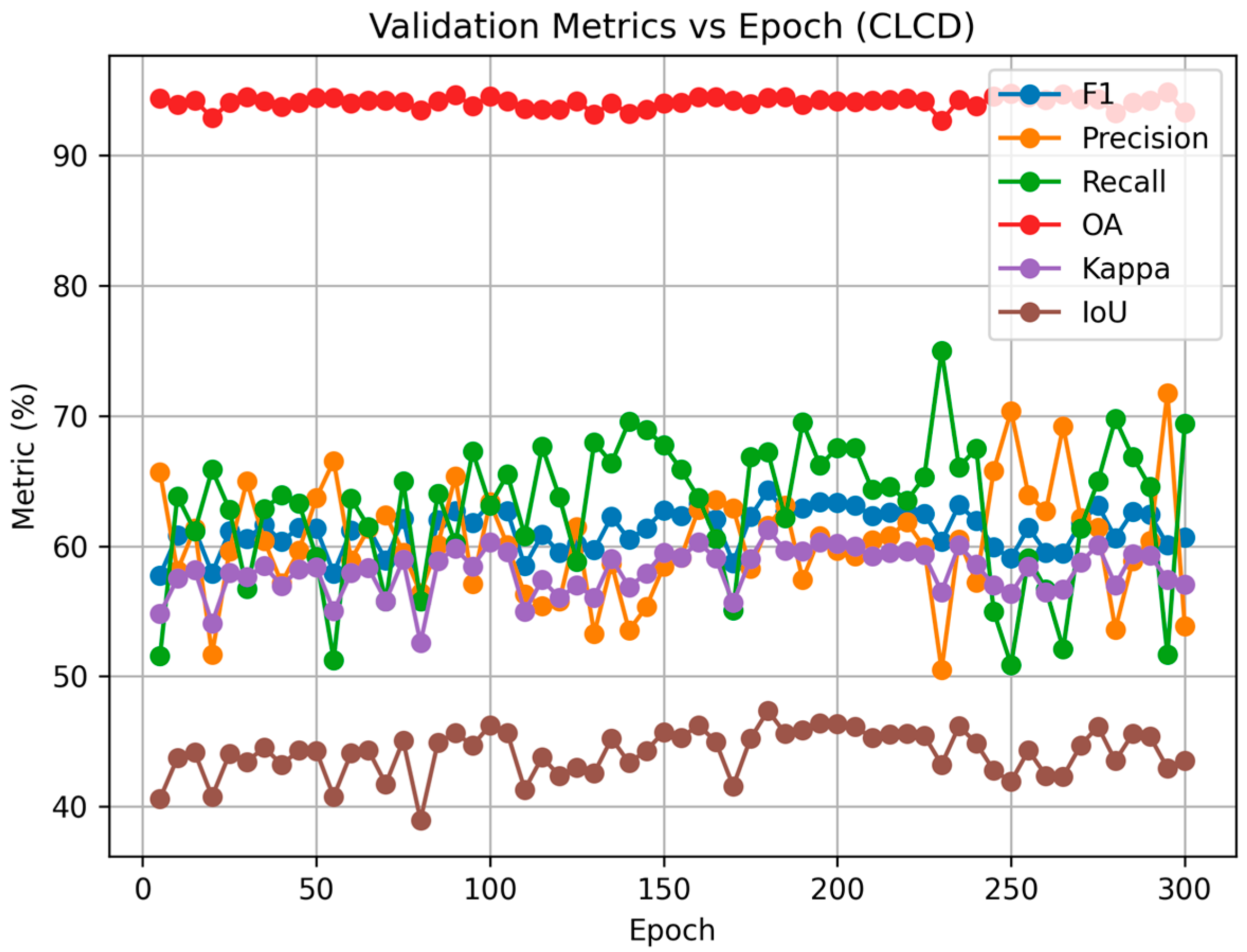

4.2. Ablation Study

- (A)

- 2 classes with a unified threshold of 0.1;

- (B)

- 2 classes with a unified threshold of 0.2;

- (C)

- 2 classes with a unified threshold of 0.3;

- (D)

- 3 classes with thresholds of 0.1 and 0.5;

- (E)

- 3 classes with thresholds of 0.05 and 0.1;

- (F)

- 5 classes with thresholds of 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, and 0.2;

- (G)

- 5 classes with thresholds of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4;

- (H)

- 5 classes with thresholds of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, and 0.7;

- (I)

- 3 classes with thresholds of 0.1 and 0.3, as proposed in this study.

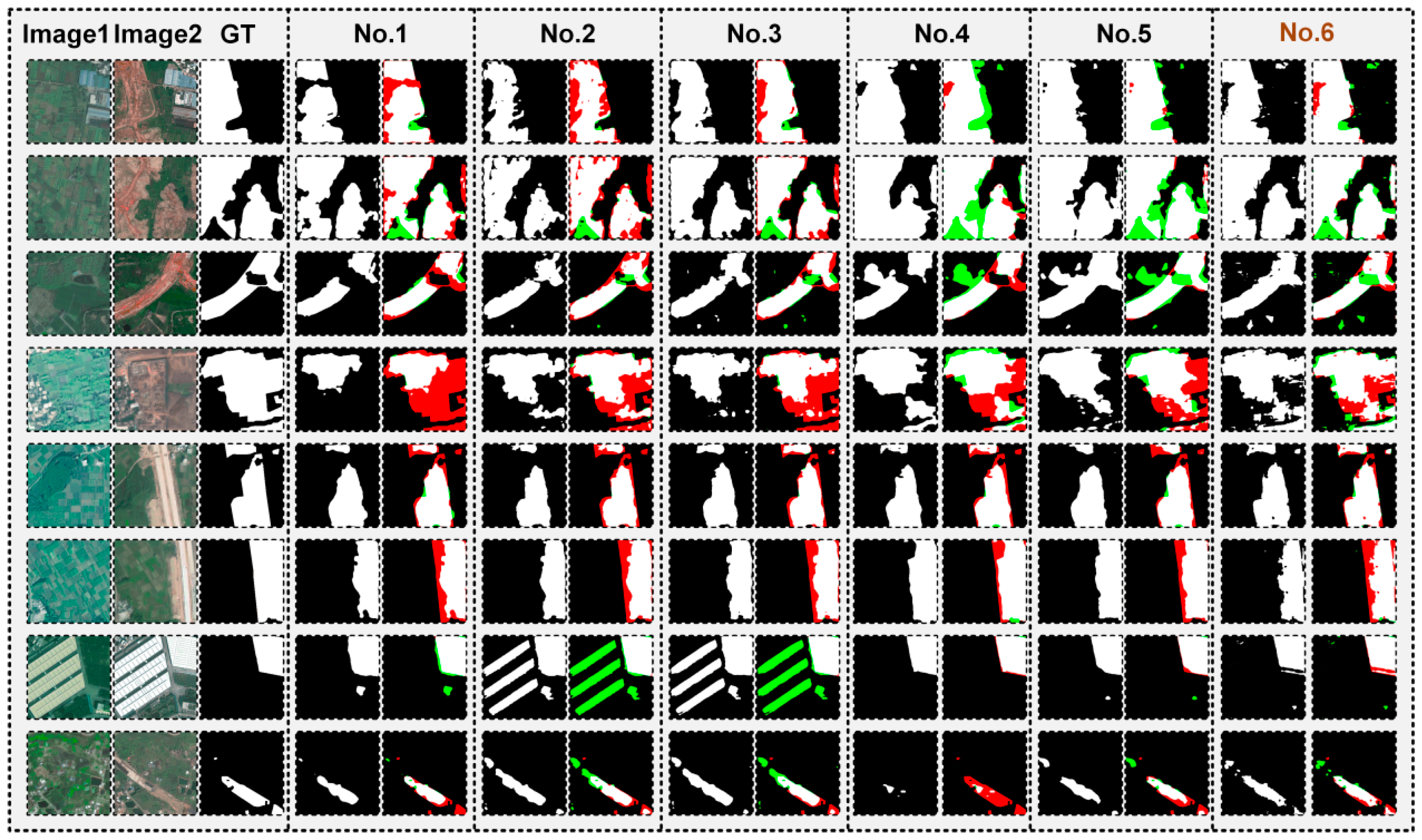

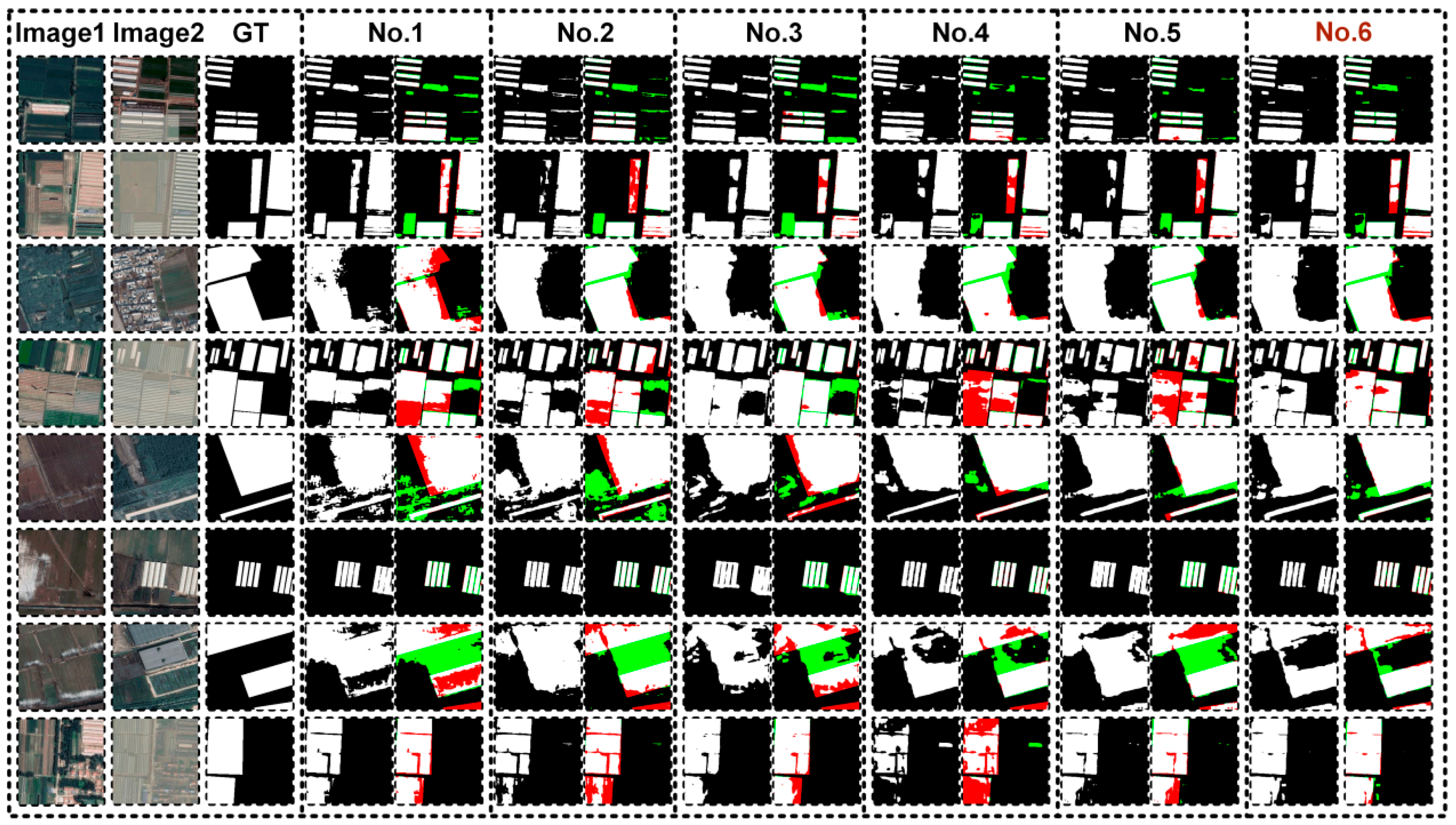

4.3. Comparative Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Yu, L.; Wu, L. Simulating the dynamics of cultivated land use in the farming regions of China: A social-economic-ecological system perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Rapid urbanization in China: A real challenge to soil protection and food security. Catena 2007, 69, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Y. Understanding the transformation of rural areal system from changes in farmland landscape: A case study of Jiaocun township, Henan province. Habitat Int. 2025, 159, 103358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Lyu, S.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xiang, S. Change detection methods for remote sensing in the last decade: A comprehensive review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yang, H.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Zhao, Q. Deep Learning-Based Change Detection in Remote Sensing: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 24415–24437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Peng, M.; Zhong, Y.; Xie, H.; Hao, Z.; Lin, J.; Ma, X.; Hu, X. A survey on deep learning-based change detection from high-resolution remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewkesbury, A.P.; Comber, A.J.; Tate, N.J.; Lamb, A.; Fisher, P.F. A critical synthesis of remotely sensed optical image change detection techniques. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 160, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omia, E.; Bae, H.; Park, E.; Kim, M.S.; Baek, I.; Kabenge, I.; Cho, B.-K. Remote sensing in field crop monitoring: A comprehensive review of sensor systems, data analyses and recent advances. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Xiang, Y.; You, H. A post-classification comparison method for SAR and optical images change detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2019, 16, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, Q. Accuracy analysis of remote sensing change detection by rule-based rationality evaluation with post-classification comparison. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2004, 25, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Guo, X.; Li, Z.; Li, D. A review of multi-class change detection for satellite remote sensing imagery. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Hu, K.; Fang, Y.; Rui, X. SChanger: Change Detection from a Semantic Change and Spatial Consistency Perspective. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 10186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Wu, C.; Guo, H.; Hu, M.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Change guiding network: Incorporating change prior to guide change detection in remote sensing imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 8395–8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–20 June 1996; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Wei, S.; Ji, S.; Lu, M. Detecting large-scale urban land cover changes from very high resolution remote sensing images using CNN-based classification. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micallef, N.; Seychell, D.; Bajada, C.J. Exploring the u-net++ model for automatic brain tumor segmentation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 125523–125539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, H. End-to-end change detection for high resolution satellite images using improved UNet++. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, S.; Idbraim, S.; Karmoude, Y.; Masse, A.; Arbelo, M. Deep-learning for change detection using multi-modal fusion of remote sensing images: A review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, R.; Mignotte, M.; Dahmane, M. Partly uncoupled siamese model for change detection from heterogeneous remote sensing imagery. J. Remote Sens. GIS 2020, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, K.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, G. Pseudo-Siamese capsule network for aerial remote sensing images change detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, N.; Kiani, A.; Ebadi, H. OctaveNet: An efficient multi-scale pseudo-siamese network for change detection in remote sensing images. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 83941–83961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xia, G.-S.; Liu, Z.; Du, B.; Yang, W.; Pelillo, M.; Zhang, L. Asymmetric siamese networks for semantic change detection in aerial images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, X.; Li, K.; Zhang, J.; Gong, J.; Zhang, M. PGA-SiamNet: Pyramid feature-based attention-guided Siamese network for remote sensing orthoimagery building change detection. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tan, K.; Jia, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y. A deep siamese network with hybrid convolutional feature extraction module for change detection based on multi-sensor remote sensing images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Cao, L.; Yan, P.; Zhu, C.; Wang, M. Remote sensing image change detection based on swin transformer and cross-attention mechanism. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Wan, Z.; Zhang, P. Fully Transformer Network for Change Detection of Remote Sensing Images; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1691–1708. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Chai, Z.; Deng, H.; Liu, R. A CNN-transformer network with multiscale context aggregation for fine-grained cropland change detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 4297–4306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhao, J.; Huang, K.; Yan, Q. Shallow-guided transformer for semantic segmentation of hyperspectral remote sensing imagery. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Huang, Q.; Wang, W.; Liu, L. Selective and multi-scale fusion mamba for medical image segmentation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 261, 125518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, G. TransUMobileNet: Integrating multi-channel attention fusion with hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture for medical image segmentation. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2025, 107, 107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Rui, X.; Zou, Y.; Tang, H.; Ouyang, N.; Ren, Y. STDPNet: Supervised transformer-driven network for high-precision oil spill segmentation in SAR imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2025, 143, 104812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Tang, L. U-mga: A multi-module unet optimized with multi-scale global attention mechanisms for fine-grained segmentation of cultivated areas. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, H.; Rui, X.; Tang, H.; Ouyang, N.; Zou, Y. MSAttU-Net: A water body extraction network for Nanjing that overcomes interference in shaded areas. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2025, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Wu, C.; Du, B. HCGMNet: A hierarchical change guiding map network for change detection. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2023 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Pasadena, CA, USA, 16–21 July 2023; pp. 5511–5514. [Google Scholar]

- Thonfeld, F. The Impact of Sensor Characteristics and Data Availability on Remote Sensing Based Change Detection. Ph.D. Thesis, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shafique, A.; Cao, G.; Khan, Z.; Asad, M.; Aslam, M. Deep learning-based change detection in remote sensing images: A review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Li, X.; Du, Z.; Shen, H. Spatiotemporal enhancement and interlevel fusion network for remote sensing images change detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, H.; He, F. MSFNet: Multi-scale Spatial-frequency Feature Fusion Network for Remote Sensing Change Detection. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 18, 1912–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Tan, C.; Gao, Z.; Xu, Y.; Chen, G.; Heng, P.-A.; Li, S.Z. A survey on generative diffusion models. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 2814–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fu, R.; Fang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y. Medsegdiff: Medical image segmentation with diffusion probabilistic model. Proc. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, 227, 1623–1639. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Ji, W.; Fu, H.; Xu, M.; Jin, Y.; Xu, Y. Medsegdiff-v2: Diffusion-based medical image segmentation with transformer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; pp. 6030–6038. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, Z.; Wan, L.; Fu, H.; Yang, G.; Yang, Y.; Yu, L.; Lei, B.; Zhu, L. Diff-UNet: A diffusion embedded network for robust 3D medical image segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2025, 105, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, T.; Shaharbany, T.; Nachmani, E.; Wolf, L. Segdiff: Image segmentation with diffusion probabilistic models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.00390. [Google Scholar]

- Baranchuk, D.; Rubachev, I.; Voynov, A.; Khrulkov, V.; Babenko, A. Label-efficient semantic segmentation with diffusion models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.03126. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Yao, L.; Deng, Y.; Hang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H. SNUNet3+: A full-scale connected Siamese network and a dataset for cultivated land change detection in high-resolution remote-sensing images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Q.; Niu, G. Transc-gd-cd: Transformer-based conditional generative diffusion change detection model. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 7144–7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.G.C.; Nair, N.G.; Patel, V.M. DDPM-CD: Denoising diffusion probabilistic models as feature extractors for remote sensing change detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 5250–5262. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Su, Q.; Wang, X. DDECNet: Dual-Branch Difference Enhanced Network with Novel Efficient Cross-Attention for Remote Sensing Change Detection; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. MF-DCMANet: A multi-feature dual-stage cross manifold attention network for PolSAR target recognition. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Backbone | FDFR | GSCA | F1 | Precision | Recall | OA | Kappa | IoU | Par. (M) | FLOPs (G) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vgg | MSAD | |||||||||||

| No.1 | √ | 57.20 | 66.84 | 50.00 | 94.03 | 54.55 | 40.06 | 32.93 | 81.42 | |||

| No.2 | √ | √ | 56.65 | 59.09 | 54.39 | 94.33 | 53.62 | 39.51 | 32.94 | 81.43 | ||

| No.3 | √ | √ | √ | 57.73 | 59.53 | 56.04 | 94.41 | 54.74 | 40.58 | 34.18 | 82.73 | |

| No.4 | √ | 60.02 | 65.28 | 55.54 | 94.96 | 57.35 | 42.88 | 28.45 | 40.26 | |||

| No.5 | √ | √ | 60.96 | 60.27 | 61.67 | 94.62 | 58.07 | 43.84 | 28.45 | 40.26 | ||

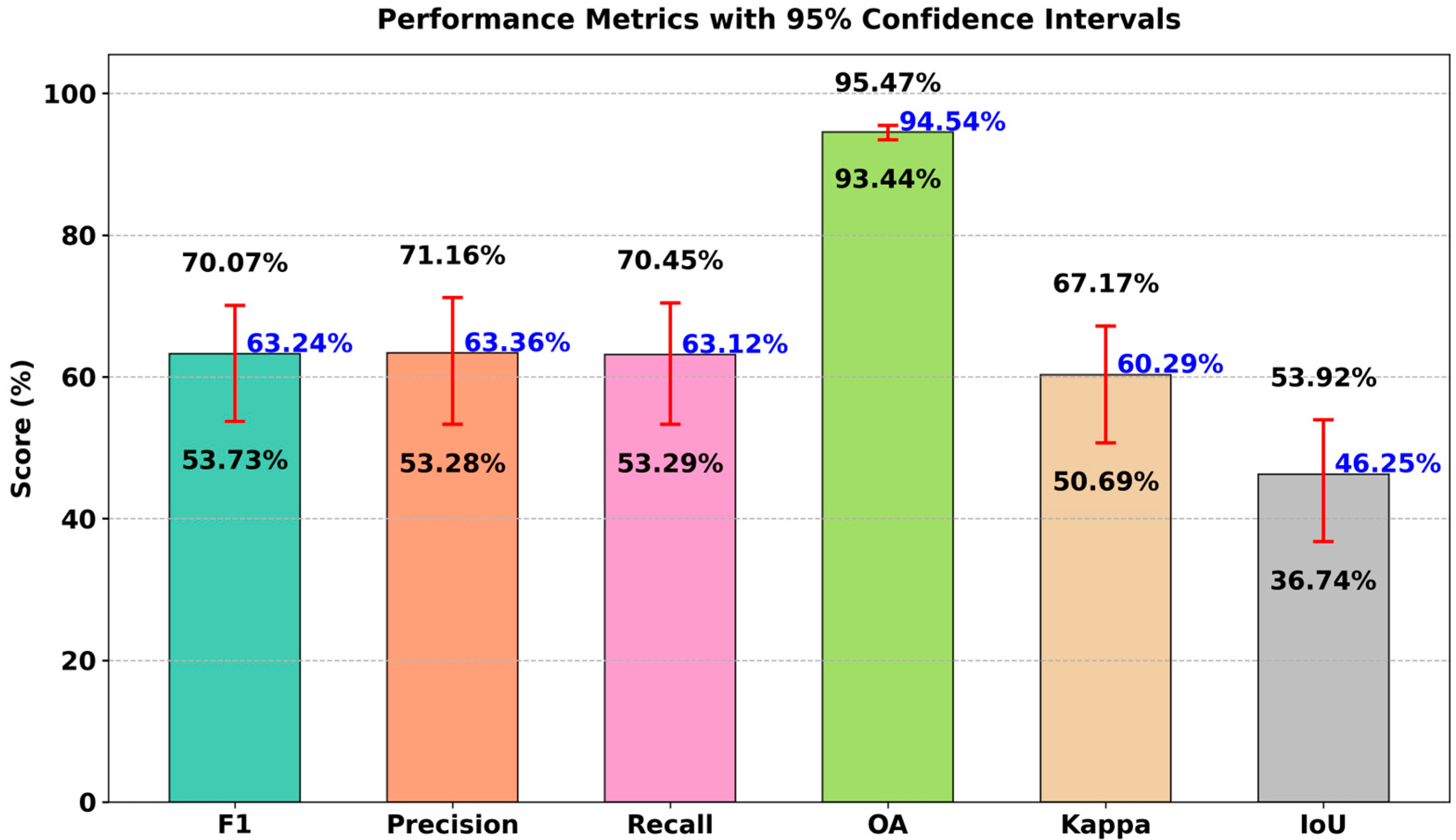

| No.6 | √ | √ | √ | 63.24 | 63.36 | 63.12 | 94.54 | 60.29 | 46.25 | 29.70 | 40.59 | |

| No. | Backbone | FDFR | GSCA | F1 | Precision | Recall | OA | Kappa | IoU | Par. (M) | FLOPs (G) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vgg | MSAD | |||||||||||

| No.1 | √ | 77.92 | 75.07 | 80.99 | 94.08 | 74.50 | 63.82 | 32.93 | 81.42 | |||

| No.2 | √ | √ | 78.68 | 78.65 | 78.71 | 94.50 | 75.52 | 64.85 | 32.93 | 81.42 | ||

| No.3 | √ | √ | √ | 78.53 | 77.04 | 80.07 | 94.35 | 75.28 | 64.65 | 34.18 | 82.73 | |

| No.4 | √ | 84.57 | 86.31 | 82.90 | 96.10 | 82.34 | 73.27 | 28.45 | 40.26 | |||

| No.5 | √ | √ | 85.44 | 85.07 | 85.81 | 96.23 | 83.27 | 74.58 | 28.45 | 40.26 | ||

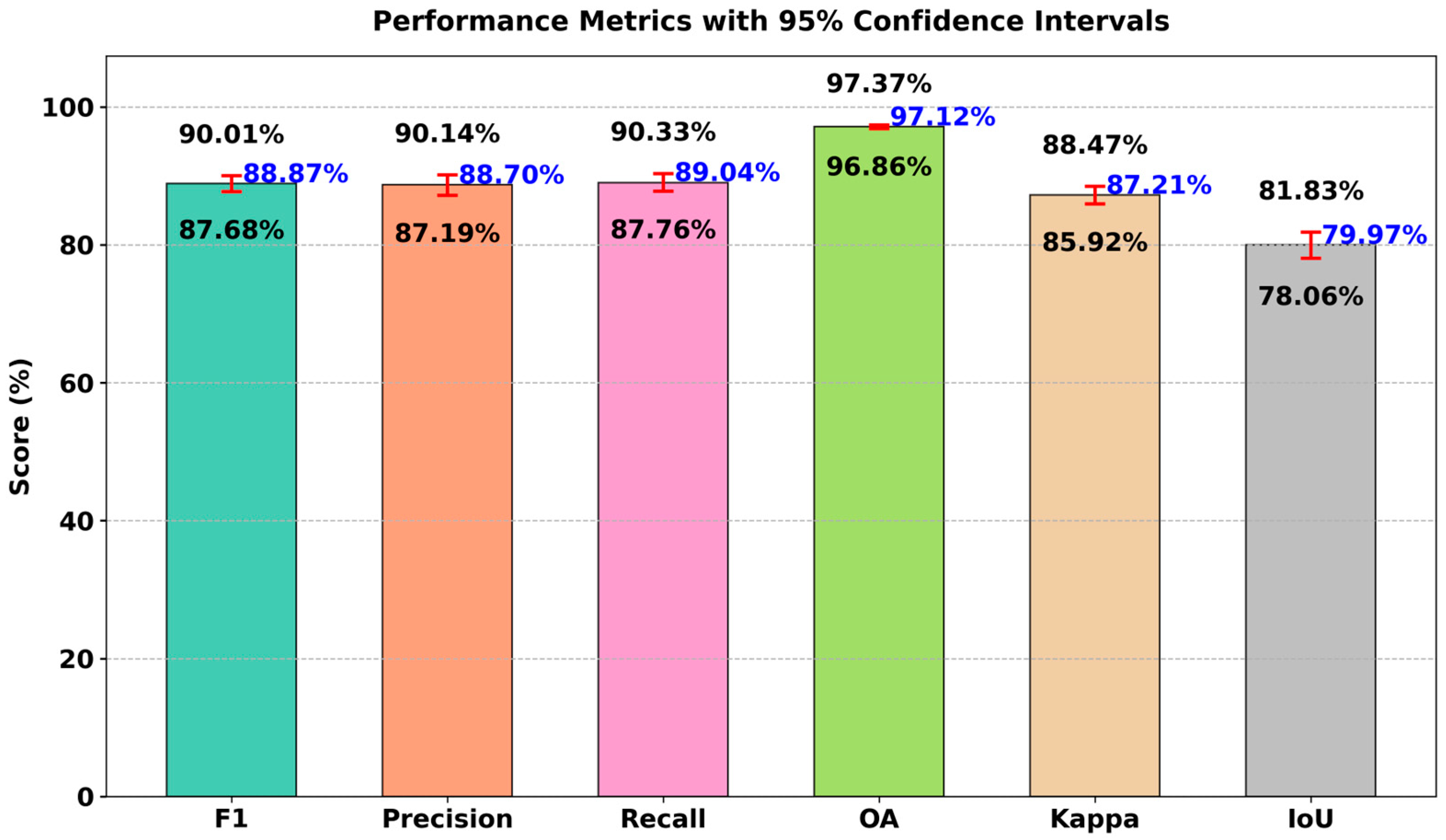

| No.6 | √ | √ | √ | 88.87 | 88.70 | 89.04 | 97.12 | 87.21 | 79.97 | 29.70 | 40.59 | |

| Conv2D + Relu | SENet | CBAM | Multi-Scale Conv. | Par. (M) | FLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| √ | 28.86 | 39.84 | |||

| √ | √ | 28.89 | 39.84 | ||

| √ | √ | 28.89 | 39.85 | ||

| √ | √ | 29.66 | 40.58 | ||

| √ | √ | √ | 28.91 | 39.85 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 29.68 | 40.58 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 29.68 | 40.59 | |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 29.70 | 40.59 |

| Net | F1 | Precision | Recall | OA | Kappa | IoU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLCD | A | 60.18 | 52.78 | 69.99 | 93.11 | 56.49 | 43.04 |

| B | 63.04 | 63.69 | 62.41 | 94.56 | 60.10 | 46.03 | |

| C | 62.84 | 62.50 | 63.19 | 94.44 | 59.84 | 45.82 | |

| D | 63.11 | 59.50 | 67.18 | 94.15 | 59.95 | 46.10 | |

| E | 61.30 | 56.78 | 66.61 | 93.74 | 57.92 | 44.20 | |

| F | 61.88 | 55.38 | 70.10 | 93.57 | 58.42 | 44.80 | |

| G | 59.63 | 52.09 | 69.72 | 92.98 | 55.87 | 42.48 | |

| H | 60.04 | 53.46 | 68.45 | 93.22 | 56.39 | 42.89 | |

| I | 63.24 | 63.36 | 63.12 | 94.54 | 60.29 | 46.25 | |

| Peixian | A | 85.40 | 82.42 | 88.62 | 96.09 | 83.15 | 74.53 |

| B | 84.86 | 81.23 | 88.82 | 95.91 | 82.50 | 73.70 | |

| C | 85.03 | 81.78 | 88.56 | 95.98 | 82.72 | 73.97 | |

| D | 85.59 | 83.16 | 88.17 | 96.17 | 83.38 | 74.81 | |

| E | 85.58 | 84.67 | 86.52 | 96.24 | 83.42 | 74.80 | |

| F | 86.18 | 86.68 | 85.70 | 96.45 | 84.15 | 75.72 | |

| G | 84.89 | 87.60 | 82.34 | 96.22 | 82.73 | 73.74 | |

| H | 85.53 | 88.11 | 83.09 | 96.37 | 83.46 | 74.72 | |

| I | 88.87 | 88.70 | 89.04 | 97.12 | 87.21 | 79.97 |

| Change | Trans. CD | SNU | HA | CG | HCGM | HSA | Farm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLCD | F1 (%) | 61.88 | 59.10 | 58.52 | 58.00 | 60.11 | 57.96 | 61.90 | 63.24 |

| Pre. (%) | 59.54 | 65.36 | 62.35 | 64.56 | 61.25 | 57.99 | 64.52 | 63.36 | |

| Rec. (%) | 64.42 | 53.93 | 55.13 | 52.65 | 59.02 | 57.92 | 59.48 | 63.12 | |

| OA (%) | 94.59 | 94.91 | 94.67 | 94.8 | 94.66 | 94.27 | 95.01 | 94.54 | |

| Kap. (%) | 58.98 | 56.41 | 55.68 | 55.26 | 57.25 | 54.88 | 59.23 | 60.29 | |

| IoU (%) | 44.81 | 41.94 | 41.36 | 40.84 | 42.97 | 40.8 | 44.82 | 46.25 | |

| Peixian | F1 (%) | 83.08 | 74.02 | 75.34 | 87.06 | 86.28 | 86.27 | 86.15 | 88.87 |

| Pre. (%) | 84.09 | 74.9 | 75.03 | 87.83 | 84.29 | 85.66 | 86.70 | 88.70 | |

| Rec. (%) | 82.08 | 73.16 | 75.65 | 86.29 | 88.36 | 86.89 | 85.61 | 89.04 | |

| OA (%) | 95.68 | 93.37 | 93.61 | 96.69 | 96.37 | 96.43 | 96.45 | 97.12 | |

| Kap. (%) | 80.6 | 70.22 | 71.67 | 85.16 | 84.19 | 84.22 | 84.11 | 87.21 | |

| IoU (%) | 71.05 | 58.76 | 60.44 | 77.08 | 75.87 | 75.86 | 75.67 | 79.97 | |

| Effi. | Par. (M) | 29.841 | 121.679 | 0.460 | 2.611 | 33.678 | 47.322 | 34.417 | 29.70 |

| FLOPs (G) | 11.649 | 46.332 | 1.312 | 17.625 | 82.234 | 318.416 | 83.042 | 40.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Qiu, S.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, L. FarmChanger: A Diffusion-Guided Network for Farmland Change Detection. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010038

Chen Y, Qiu S, Yang Y, Liu Z, Yao W, Zhang Y, Tang L. FarmChanger: A Diffusion-Guided Network for Farmland Change Detection. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yun, Shi Qiu, Yanli Yang, Zhaoyan Liu, Weiyuan Yao, Yu Zhang, and Lingli Tang. 2026. "FarmChanger: A Diffusion-Guided Network for Farmland Change Detection" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010038

APA StyleChen, Y., Qiu, S., Yang, Y., Liu, Z., Yao, W., Zhang, Y., & Tang, L. (2026). FarmChanger: A Diffusion-Guided Network for Farmland Change Detection. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010038