A key observation is that certain scattering matrix structures remain invariant under double-pass Faraday rotation. Specifically, consider the two basis matrices:

Any linear combination of these base matrices satisfies the following invariance property:

where

denotes the Faraday rotation matrix. This invariance property implies that when a scattering matrix can be expressed as a linear combination of

and

, its observed response is unaffected by Faraday rotation. The dihedral reflector rotated by an arbitrary angle

satisfies this condition, and its scattering matrix is given by:

Unlike the methods discussed earlier that assume a constant Faraday rotation angle across the entire image, the proposed calibration method relies exclusively on dihedral reflectors. As shown in Equation (

7), the dihedral scattering matrix satisfies the double-pass Faraday rotation invariance property, meaning its polarimetric response remains unchanged after undergoing any arbitrary Faraday rotation. This implies that regardless of ionospheric conditions, the observed response from a dihedral reflector depends solely on the system distortion parameters and is completely decoupled from the Faraday rotation angle. Consequently, the proposed method requires neither estimation nor compensation of the Faraday rotation angle, and is immune to its spatial variations—even when calibrators at different locations within the calibration site experience different levels of Faraday rotation, the parameter estimation results remain accurate. This inherent property makes the proposed method particularly well-suited for low-frequency SAR systems (e.g., P-band and L-band) where ionospheric effects are pronounced.

When the dihedral reflector is rotated by 0°, 45°, 22.5°, and 67.5°, respectively, and substituted into (

5), the resulting observed vectors are given in (

9), where

I denotes an unknown absolute factor. Any two dihedral angles can be selected to obtain four complex observations, which yield four complex unknowns in the estimation equations. The estimation results for the distortion parameters are given in Equations (10)–(15) for six dihedral combinations, where each combination yields two solution pairs: Solution I (

,

) and Solution II (

,

).

2.3.1. Mathematical Properties of the Solution Pairs

From Equation (

3), when the transmit crosstalk is negligible (

), the equivalent crosstalk simplifies to:

where

denotes the transmit channel imbalance. For

to exceed 0 dB (i.e.,

), the phase of

must approach

.

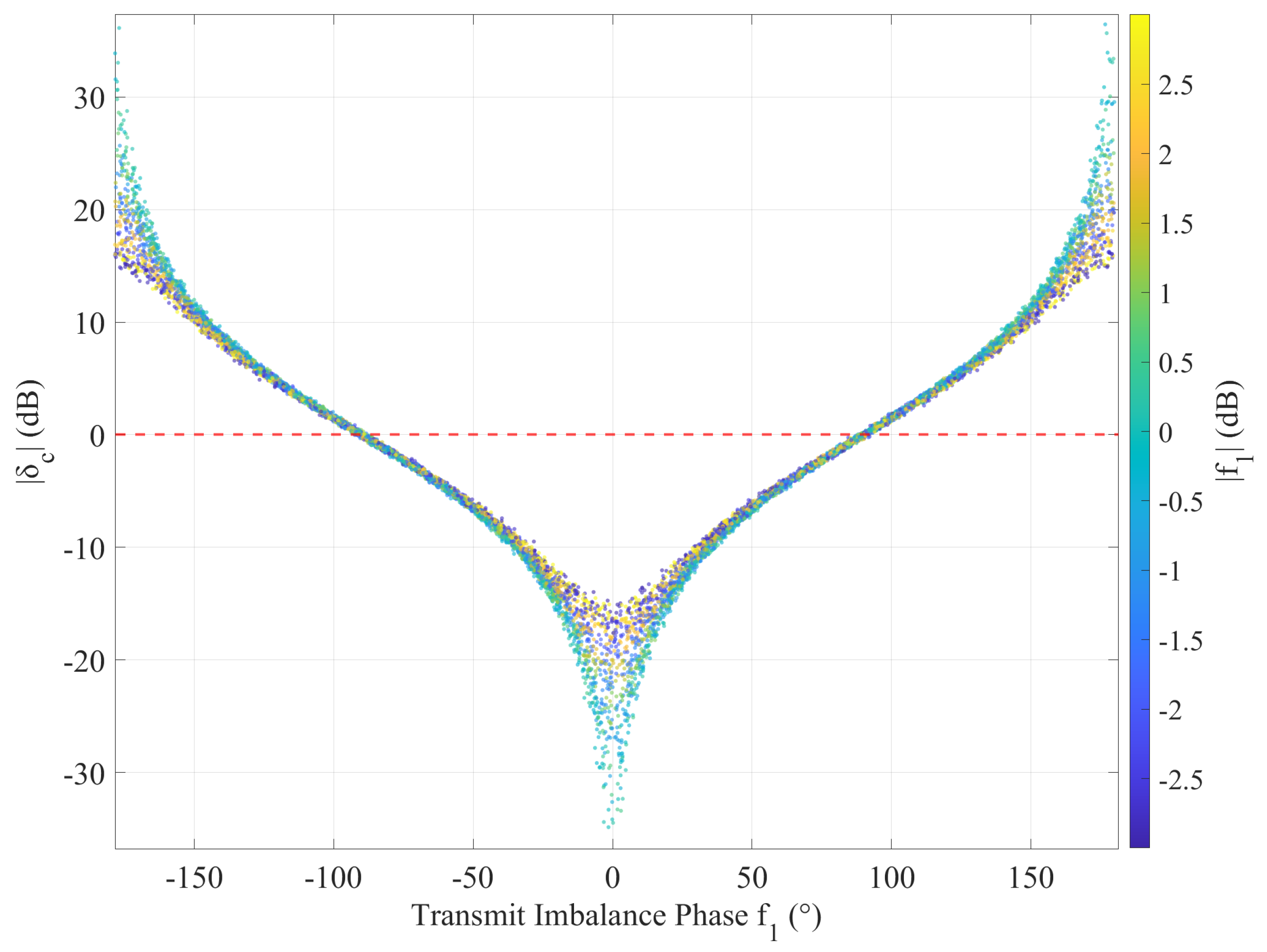

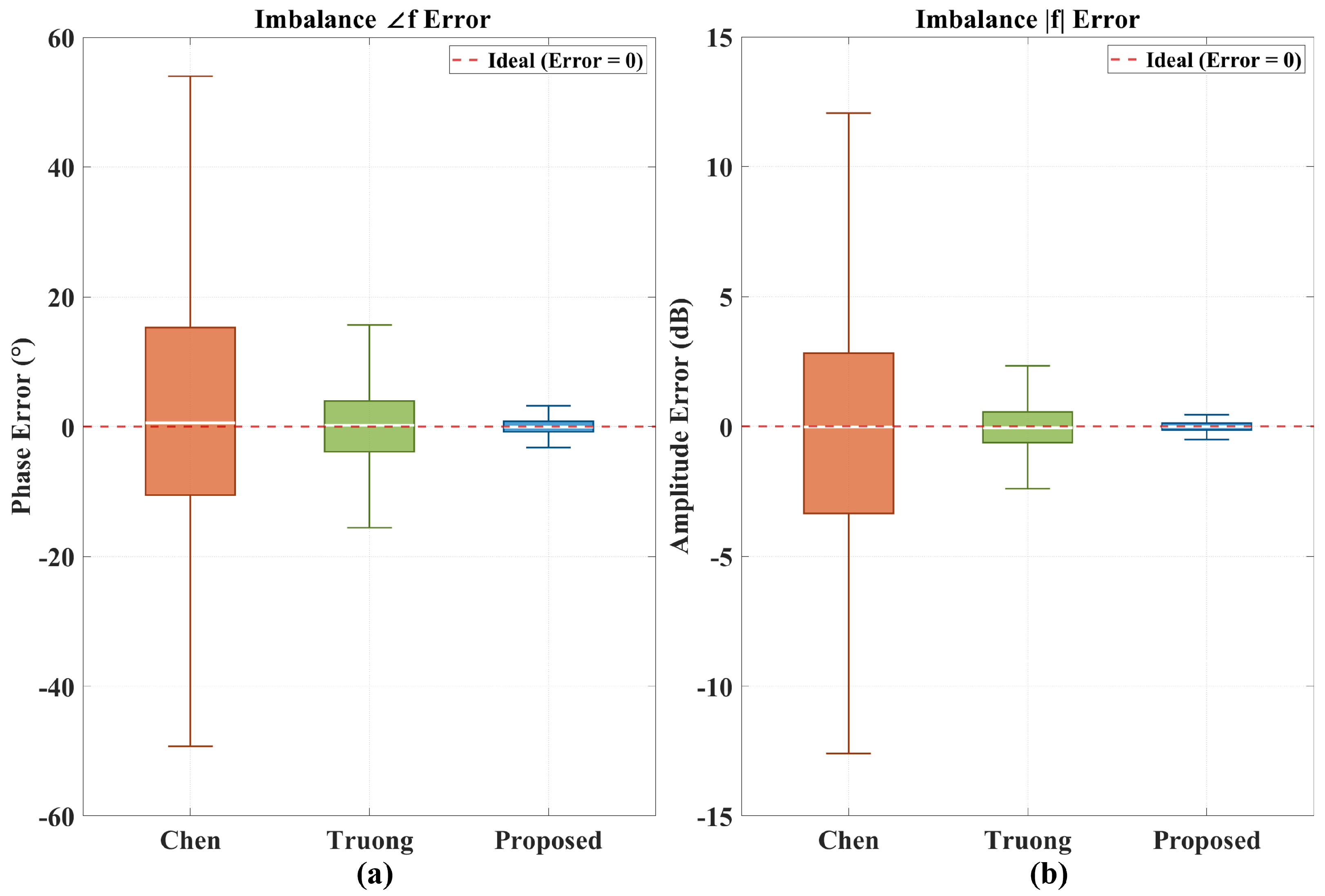

To comprehensively evaluate the range of

under various distortion conditions, Monte Carlo simulations were conducted with 10,000 trials. The distortion parameters were randomly generated within the ranges specified in

Table 1, which represent realistic or even exaggerated system conditions.

The simulation results are illustrated in

Figure 2. The scatter plot clearly demonstrates that the phase imbalance of

is the dominant factor affecting

. Across all 10,000 random trials,

exceeded 0 dB only when the phase imbalance approached the extreme values of

.

The simulation results reveal a clear correspondence among the transmit imbalance phase , the equivalent crosstalk magnitude , and the transmitted polarization state:

When : dB, RHCP component dominates, the transmitted wave is right-hand elliptically polarized

When : dB, LHCP and RHCP components have equal amplitudes, the transmitted wave degenerates into linear polarization

When : dB, LHCP component dominates, the transmitted wave becomes left-hand elliptically polarized

Therefore, represents the critical point where the circular polarization sense reverses.

Under normal circumstances, after adjustment in an anechoic chamber, the transmit antenna can be ensured to radiate a right-hand elliptically polarized wave, which at least will not degenerate into linear polarization or even left-hand elliptical polarization. This implies that the prior knowledge of “transmission dominated by RHCP” holds, i.e., dB.

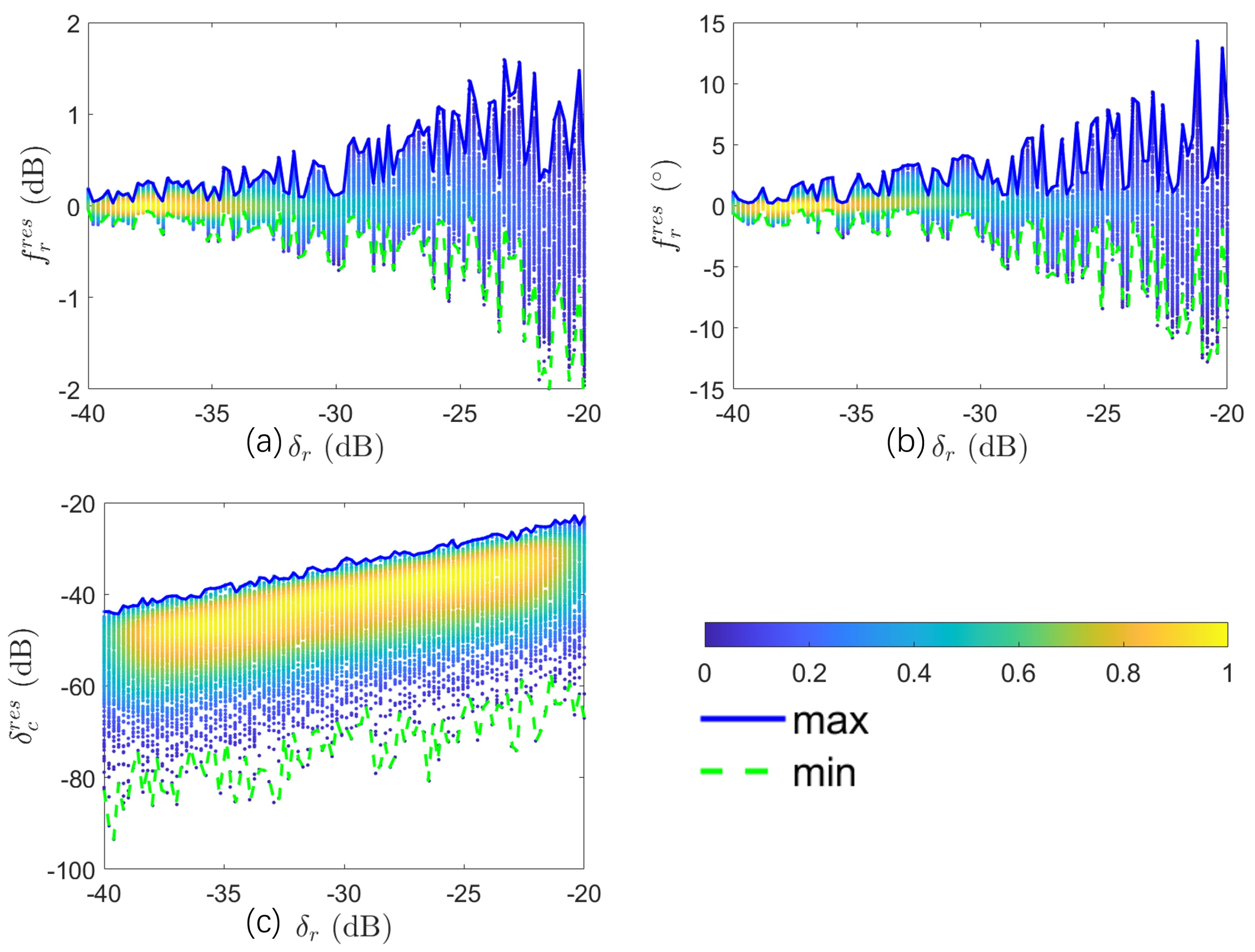

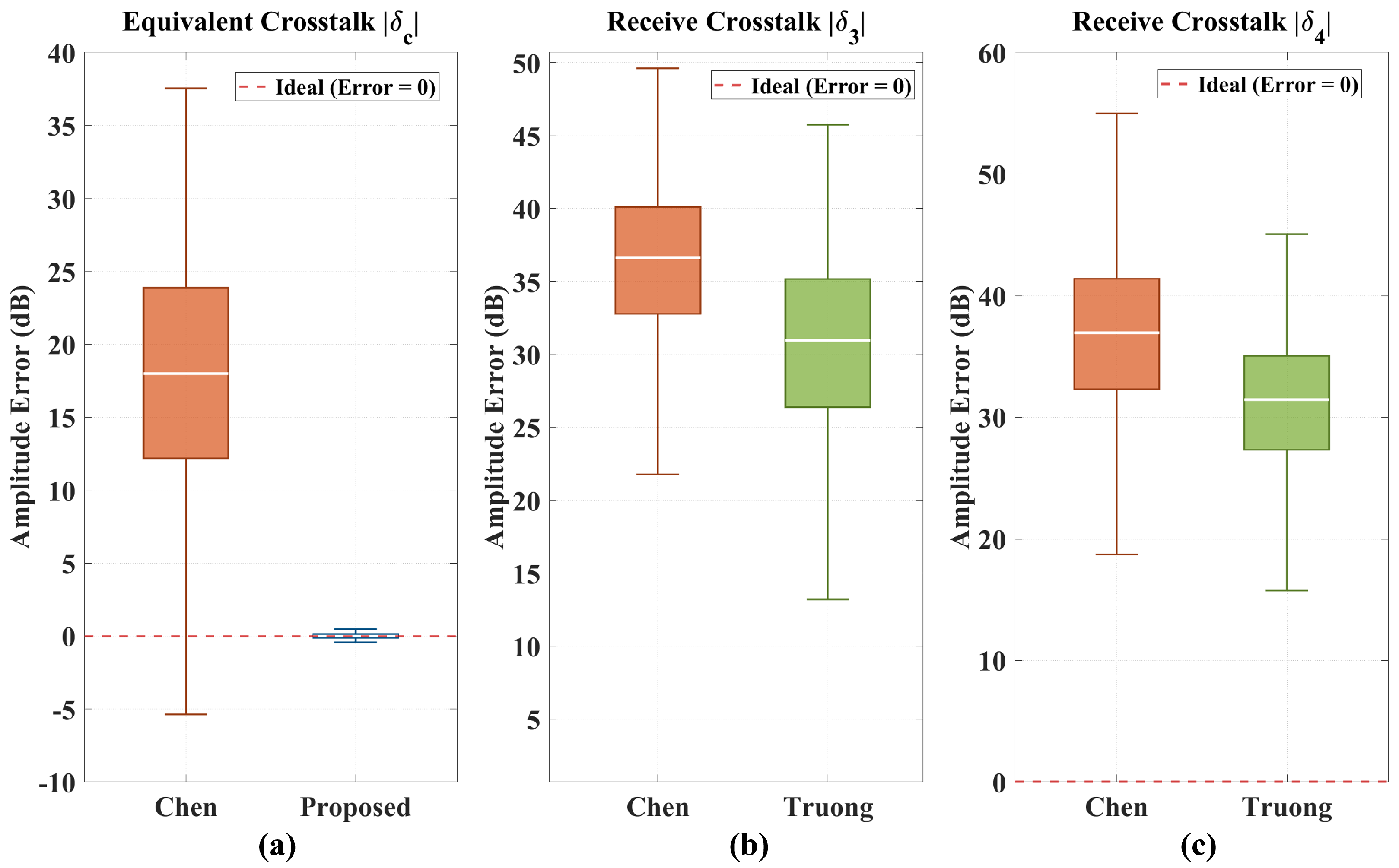

As discussed previously, each dihedral combination yields two solution pairs

and

, of which only one corresponds to the true distortion parameters. To demonstrate how to eliminate the ambiguous solution using prior knowledge, Monte Carlo simulations are conducted using the 0° and 45° dihedral combination as an example. The simulation parameters are configured as shown in

Table 2.

The equivalent crosstalk amplitude is swept from

dB to

dB, while all other parameters, including receive imbalance, calibrator gains, and Faraday rotation angle, are randomly generated within their respective ranges to verify the algorithm’s robustness. The simulation results are shown in

Figure 3. The magnitudes of the two estimated

values form two distinct lines symmetric about 0 dB, with the lower line corresponding to the correct solution. Therefore, the ambiguity elimination criterion is as follows: after computing

and

, the solution with magnitude less than 0 dB is selected as the true estimate of the equivalent crosstalk, and the corresponding

or

is taken as the correct estimate of the receive imbalance.

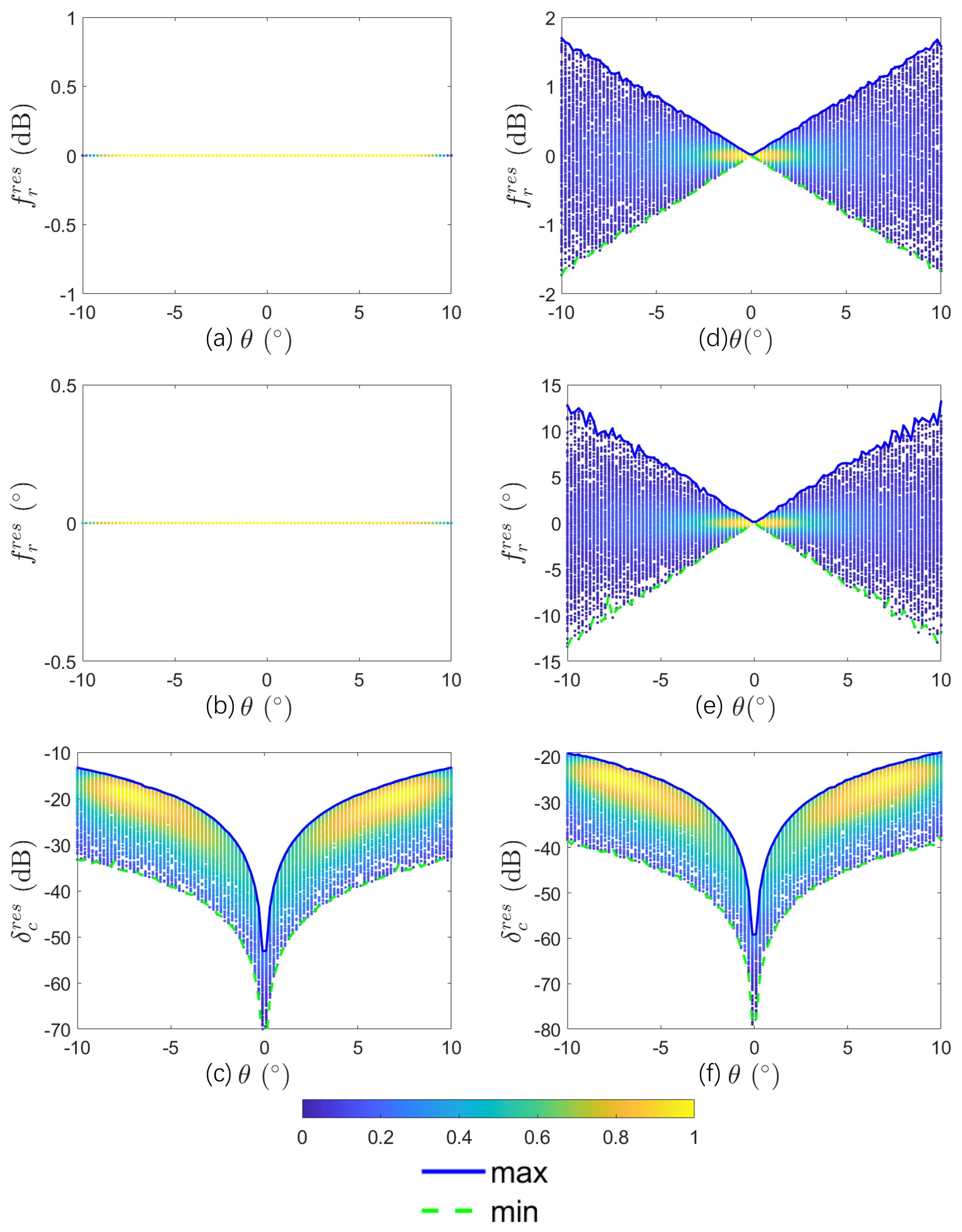

To make the algorithm applicable to more general scenarios, this section considers cases where the prior knowledge does not hold. When the RHCP characteristic of the transmit antenna cannot be guaranteed, and the polarization sense is severely distorted to linear polarization or even LHCP, the prior knowledge of dB is no longer valid, and the ambiguity elimination criterion of Method I will fail. To address this issue, this section proposes a cross-validation-based ambiguity elimination method.

From the analysis in the previous section, we know that the magnitudes of the two

solutions are symmetric about 0 dB, i.e.,

. This section further analyzes the complex product relationship between the two solutions. Through derivation, it can be shown that solutions from different dihedral combinations satisfy

, where

P is a constant related to the specific combination, as shown in

Table 3.

As shown in the table, different combinations have different product constants P, which forms the theoretical basis for the cross-validation method. Consider using three dihedral calibrators (e.g., 0°, 45°, and 22.5°), which can form two equation sets: Combination I (0° + 45°, ) and Combination II (0° + 22.5°, ). Since the two combinations have different P values (1 and j, respectively), the true solutions remain identical while the ambiguous solutions differ by a 90° phase. Therefore, the ambiguity elimination criterion is as follows: solve the two equation sets separately to obtain four solutions, and the two solutions that are numerically close to each other are the true solutions. This method requires at least three dihedral calibrators, and the two selected equation sets must have different product constants P. As shown in the table, combination pairs with identical P values should be avoided. For example, 0° + 22.5° and 45° + 67.5° both have , making it impossible to distinguish between the true and ambiguous solutions through cross-validation.

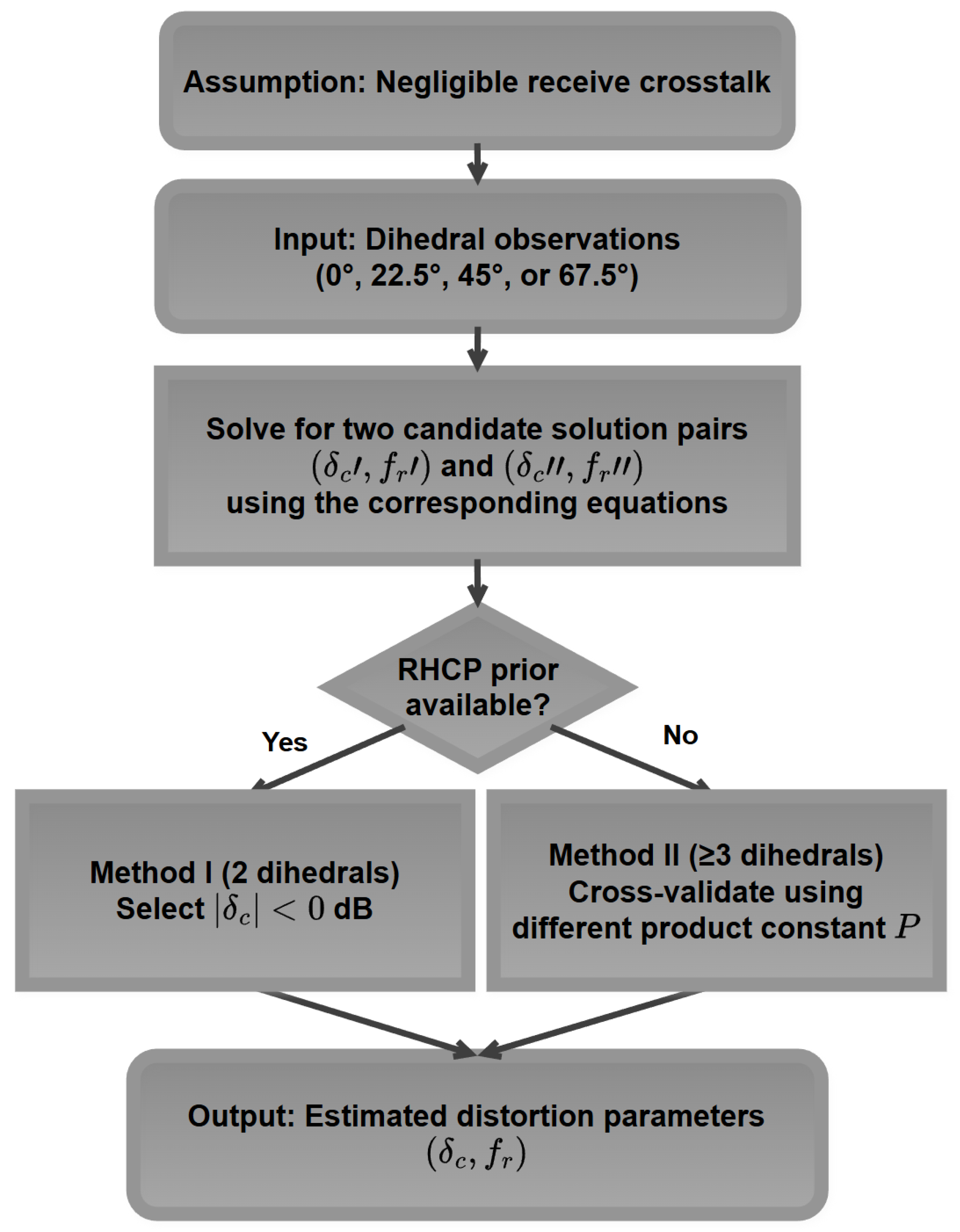

To provide a clear overview of the proposed calibration algorithm, the processing flowchart is illustrated in

Figure 4. The algorithm first assumes negligible received crosstalk, then takes dihedral observations as input and solves for two candidate solution pairs using the corresponding equations. The ambiguity elimination step selects the correct solution based on either the RHCP prior (Method I, requiring only 2 dihedrals) or cross-validation with different product constants (Method II, requiring at least 3 dihedrals). Finally, the estimated distortion parameters

are output.

2.3.2. Extension to /4 Mode

The proposed calibration framework can be extended to the /4 mode by replacing the circularly polarized transmission vector with a 45° linearly polarized vector. In the /4 mode, the ideal transmission polarization is , and the equivalent crosstalk represents the ratio of the linearly polarized component to the ideal component.

However, mathematical analysis reveals that the solution symmetry property does not hold for all dihedral combinations in the /4 mode. Only the 0° + 45° combination yields two solutions that are symmetric about 0 dB (i.e., ), enabling ambiguity elimination via Method I when the equivalent crosstalk is small. For other dihedral combinations, the product of the two solutions is no longer a fixed constant but depends on the observation values themselves, which is in stark contrast to the CTLR mode. In the CTLR mode, all combinations yield solution products that are fixed constants (1, , j, or ), with deterministic phase differences between different combinations that can be exploited for cross-validation and ambiguity identification. The /4 mode lacks this property; when the equivalent crosstalk exceeds 0 dB, Method II cannot be used for ambiguity elimination, and the ambiguity elimination mechanism requires further investigation. Therefore, for the /4 mode, the proposed method is currently applicable only to the 0°+45° dihedral combination with Method I (the dB prior), and the solution equations are given in (17).

/4 Mode—Combination: 0° + 45°