High-Rise Building Area Extraction Based on Prior-Embedded Dual-Branch Neural Network

Highlights

- Prior-Embedded Dual-Branch Neural Network (PEDNet) demonstrates strong generalization across wide geographic regions and large timestamp spans in high-rise building area (HRB) extraction from Sentinel-2 imagery by successfully balancing global features with local details and embedding diverse prior information.

- This robust method enables more frequent and accurate HRB extraction in a national scale, supporting urban planning and environmental assessment.

Abstract

1. Introduction

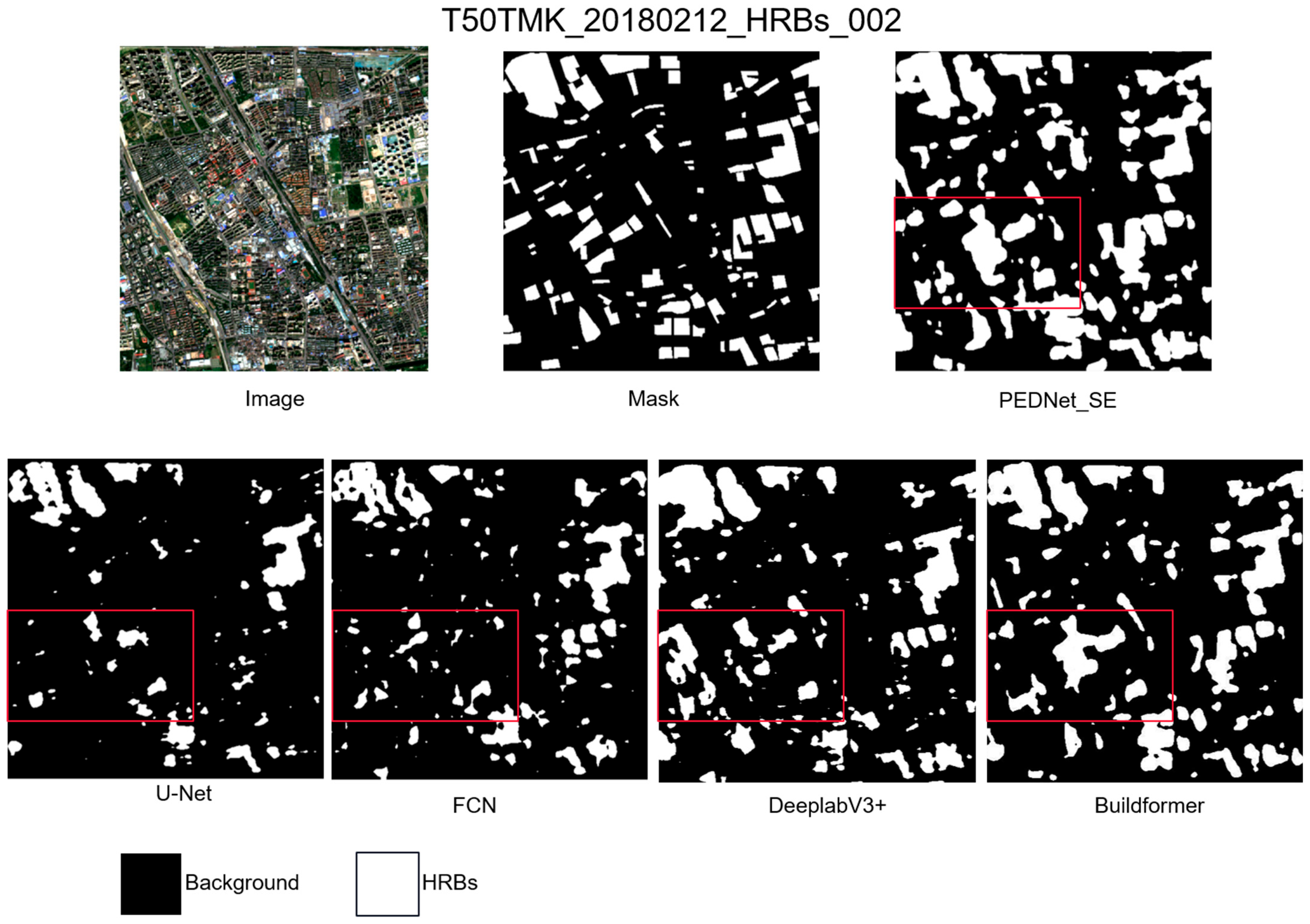

- This study proposes a prior-aware dual-path segmentation framework, termed PEDNet, for the extraction of HRBs from optical remote sensing imagery. The performance of PEDNet is systematically evaluated and compared with representative baseline models, including classical CNN-based architectures (e.g., FCN), a strong CNN-based segmentation model (DeepLabV3+), and a modern Transformer-based building extraction model (BuildFormer). The results demonstrate that PEDNet achieves superior performance and robustness in complex urban scenarios.

- In scenarios involving data combination across multiple regions and time periods, the study validates the extraction advantages of the PEDNet model, thereby substantiating its capacity to circumvent the limitations associated with “local models”. The model demonstrates enhanced robustness in HRB extraction tasks across multiple regions and all seasons, providing a feasible basis for a single model to achieve wide geographic span and cross-timestamp HRB extraction.

2. Materials and Methods

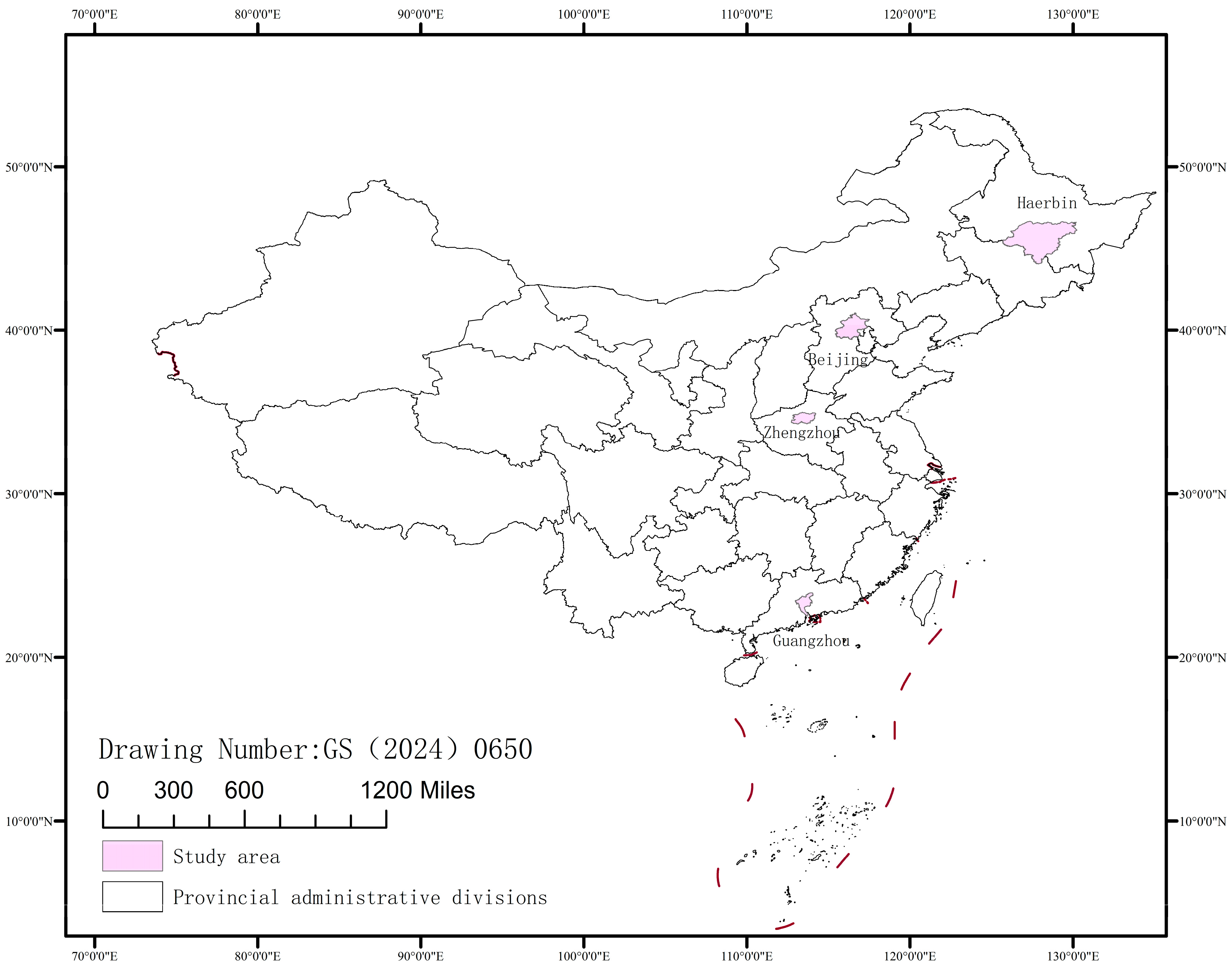

2.1. Data

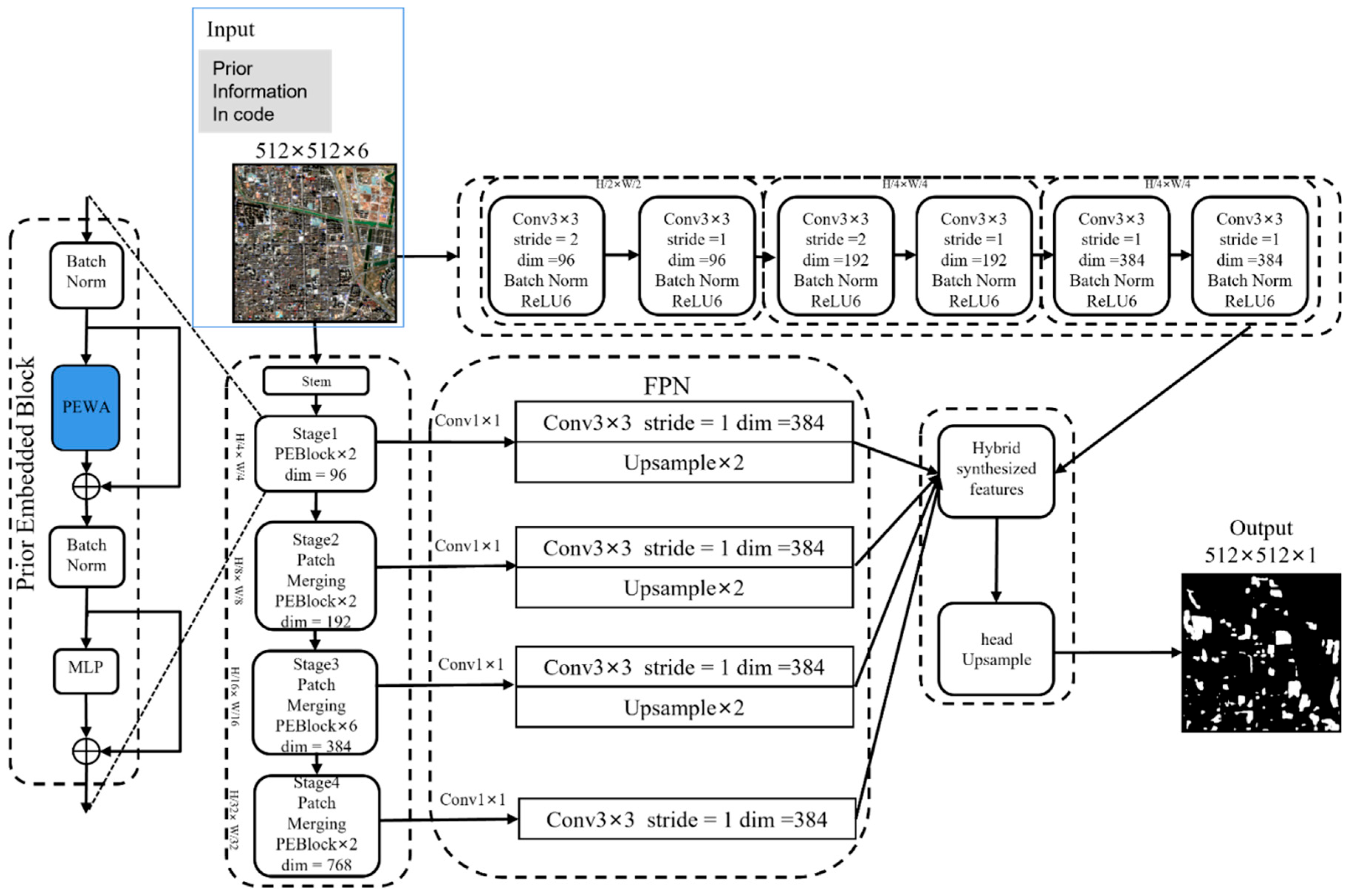

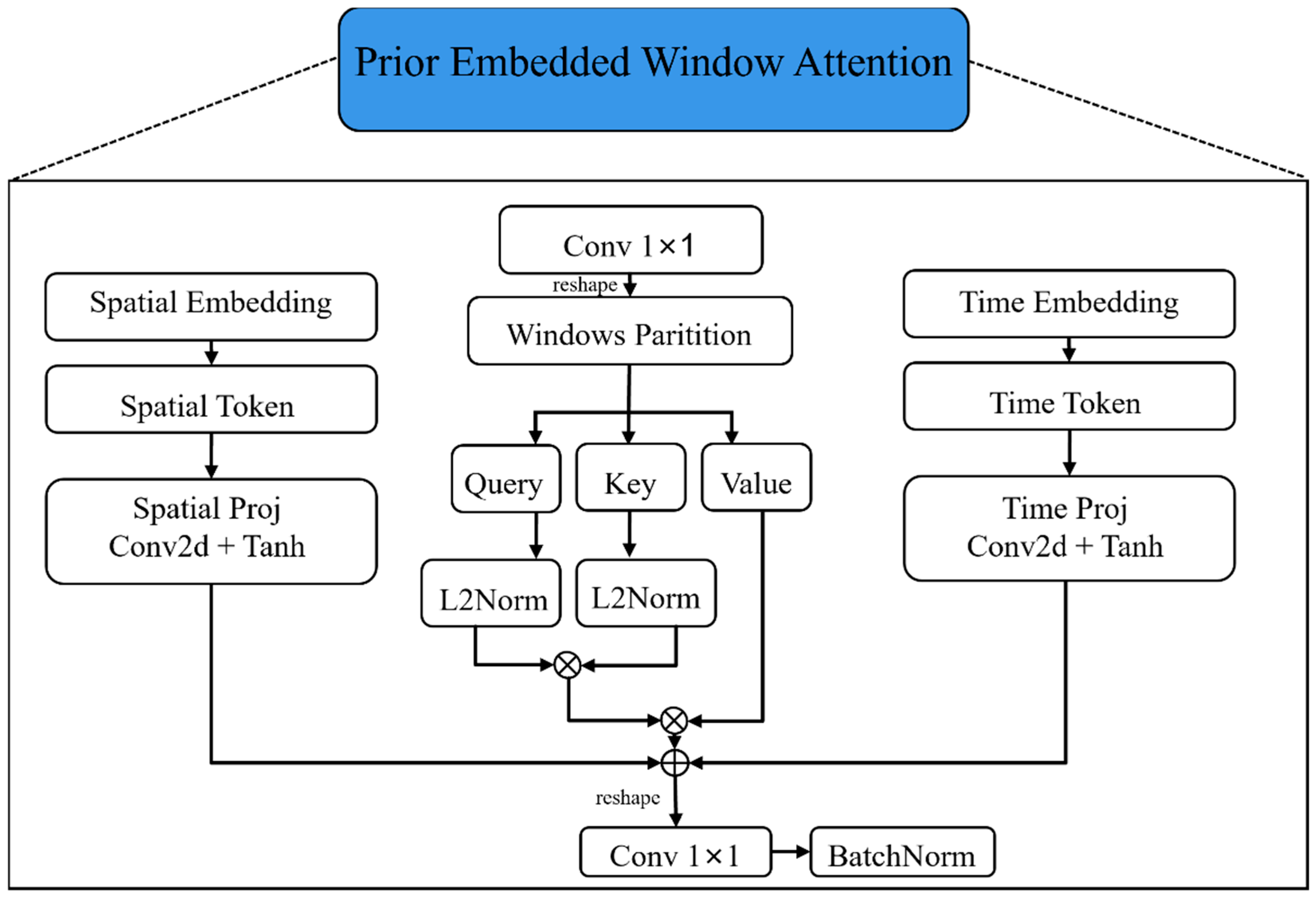

2.2. PEDNet

2.2.1. Network Architecture

2.2.2. Loss Function

2.3. Evaluation Metrics

2.4. Experimental Design

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Results of PEDNet Model

- PEDNet_Base: Disables the SE and TE mechanisms in PEWA, retaining only the basic attention structure. PEWA then relies solely on the raw spectral and spatial features of pixels within the window for self-attention calculations. Feature dimension reduction is achieved through multiple layers of PEBlock (including the PEWA base module and MLP) and PatchMerging without introducing spatial or timestamp information.

- PEDNet_SE: Enables the SE mechanism in PEWA and disables the TE mechanism. Specifically, the SE module converts regional input information (e.g., city codes) into high-dimensional feature vectors. These vectors are then mapped by the Spatial Projection Layer (Spatial Proj) into spatial attention corresponding to the number of attention heads. These vectors participate in the calculation of attention weights within the window, enabling the model to learn regional spatial features.

- PEDNet_TE: Enables the TE mechanism in PEWA while disabling SE. The TE module converts timestamp information (year and Julian day) into high-dimensional feature vectors. These vectors are then mapped by the Temporal Projection Layer (Temporal Proj) to generate temporal attention. This enables timestamp information to participate in PEWA’s attention modulation learning.

- PEDNet_SE + TE: Enables both the SE and TE mechanisms in PEWA. Both mechanisms act as dual biases that collaborate in the attention calculation process. Spatial and timestamp information are learned in parallel during the window attention calculation of PEWA.

3.2. Comparison with Traditional Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.; Liu, M.; Hu, Y.; Li, C.; Xiong, Z. Analysis of Three-Dimensional Space Expansion Characteristics in Old Industrial Area Renewal Using GIS and Barista: A Case Study of Tiexi District, Shenyang, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Du, Z.J.; Zhang, J.B.; Liu, Y.L.; Xu, S.W.; Lu, Q.; Shan, L.X.; Liu, D.M.; Zhang, L.P.; et al. Unified Standards for Civil Building Design (GB 50352-2019). Constr. Sci. Technol. 2021, 13, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Lee, K.; Lee, W.H. Object-Based High-Rise Building Detection Using Morphological Building Index and Digital Map. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, B. Detecting High-Rise Buildings from Sentinel-2 Data Based on Deep Learning Method. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Li, L.; Cheng, G.; Zhang, B. Analyzing Long-Term High-Rise Building Areas Changes Using Deep Learning and Multisource Satellite Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaloni; Dixit, M.; Agarwal, S.; Gupta, P. Building Extraction from Remote Sensing Images: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2020 2nd International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication Control and Networking (ICACCCN), Online, 18–19 December 2020; pp. 966–971. [Google Scholar]

- Dunaeva, A. Building Footprint Extraction from Stereo Satellite Imagery Using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Multi-Conference on Engineering, Computer and Information Sciences (SIBIRCON), Novosibirsk, Russia, 21–27 October 2019; pp. 0557–0559. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Cord, M.; Douze, M.; Massa, F.; Sablayrolles, A.; Jegou, H. Training data-efficient image transformers & distillation through attention. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning, Online, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 10347–10357. [Google Scholar]

- Shleifer, S.; Weston, J.; Ott, M. Normformer: Improved transformer pretraining with extra normalization. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.09456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Yan, P. An improved semantic segmentation algorithm for high-resolution remote sensing images based on DeepLabv3+. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Fang, S.; Meng, X.; Li, R.; Sensing, R. Building extraction with vision transformer. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5625711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y. A Dual-Branch Network Based on ViT and Mamba for Semantic Segmentation of Remote Sensing Image. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Signal, Information and Data Processing (ICSIDP), Zhuhai, China, 22–24 November 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Su, Y.; Deng, C.; Xia, Z.; Tashi, N. Global Adaptive Second-Order Transformer for Remote Sensing Image Semantic Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5640417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, D. Building Extraction from Remote Sensing Images by Fusing Mask R-CNN and Attention Mechanisms. Int. J. Netw. Secur. 2025, 27, 356–367. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q.; Xia, B. Cross-level and multiscale CNN-Transformer network for automatic building extraction from remote sensing imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 2893–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiming, T.; Tang, X.; Shang, H. A shape-aware enhancement Vision Transformer for building extraction from remote sensing imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 1250–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Xu, W. MSST-Net: A Multi-Scale Adaptive Network for Building Extraction from Remote Sensing Images Based on Swin Transformer. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirko, W.; Brempong, E.A.; Marcos, J.T.; Annkah, A.; Korme, A.; Hassen, M.A.; Sapkota, K.; Shekel, T.; Diack, A.; Nevo, S. High-resolution building and road detection from sentinel-2. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.11622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Meng, X. Text Semantics-Driven Remote Sensing Image Feature Extraction. Spacecr. Recovery Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Q.; Qin, J.; Yao, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, H. Buildings extraction of GF-2 remote sensing image based on multi-layer perception network. Remote Sens. Nat. Resour. 2021, 33, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhang, Q. Building extraction using high-resolution satellite imagery based on an attention enhanced full convolution neural network. Remote Sens. Nat. Resour. 2021, 33, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y. PolyBuilding: Polygon transformer for building extraction. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 199, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zou, Z.; Shi, Z. Building Extraction from Remote Sensing Images with Sparse Token Transformers. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

|---|---|

| HRBs | High-Rise Building Areas |

| PEDNet | Prior-Embedded Dual-branch Network |

| PEWA | Prior-Embedded Window Attention |

| PEBlock | Prior-Embedded Block |

| SE | Spatial Embedding |

| TE | Time Embedding |

| DOY | Day of Year |

| Title City | T51TYL (Harbin) | T50TMK (Beijing) | T49SGU (Zhengzhou) | T49QGF (Guangzhou) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Group | |||||

| Data A | 22 March 2018 | 12 February 2018 | 22 February 2018 | 15 January 2018 | |

| Data B | 23 June 2018 | 14 June 2018 | 07 June 2018 | 11 March 2018 | |

| Data C | 18 September 2018 | 05 September 2018 | 30 September 2018 | 14 June 2018 | |

| Data D | 10 December 2018 | 19 December 2018 | 29 December 2018 | 02 October 2018 | |

| Model | F1/% | IoU/% | OA/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDNet_Base | 57.4 | 40.3 | 91.1 |

| PEDNet_SE | 62.8 | 45.8 | 91.3 |

| PEDNet_TE | 61.4 | 44.3 | 91.2 |

| PEDNet_SE + TE | 60.5 | 43.4 | 91.2 |

| Model | F1/% | IoU/% | OA/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 54.8 | 42.3 | 90.2 |

| FCN | 55.8 | 38.1 | 90.1 |

| Deeplabv3+ | 56.2 | 42.5 | 90.5 |

| Buildformer | 57.8 | 43.4 | 90.6 |

| PEDNet_SE | 62.8 | 45.8 | 91.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Si, Q.; Li, L.; Cheng, G. High-Rise Building Area Extraction Based on Prior-Embedded Dual-Branch Neural Network. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010167

Si Q, Li L, Cheng G. High-Rise Building Area Extraction Based on Prior-Embedded Dual-Branch Neural Network. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):167. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010167

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Qiliang, Liwei Li, and Gang Cheng. 2026. "High-Rise Building Area Extraction Based on Prior-Embedded Dual-Branch Neural Network" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010167

APA StyleSi, Q., Li, L., & Cheng, G. (2026). High-Rise Building Area Extraction Based on Prior-Embedded Dual-Branch Neural Network. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010167