1. Introduction

The Fengyun-4M (FY-4M) satellite, scheduled for launch in 2026, will be the world’s first geostationary one with passive-microwave observation capability. Its successful utilization will enable high-temporal-frequency vertical sounding of clouds and precipitation, marking a significant advance in measuring atmospheric profiles from geostationary platform. Particularly, the 183 GHz frequency band is considered as one of key channels for atmospheric water vapor sounding. However, high-temporal-frequency observations on this band are unavailable. Therefore, to support certain typical quantitative applications such as temperature, humidity, and wind retrievals, as well as data assimilation, some simulated BT datasets for 183 GHz band are in need.

The accuracy of BT simulations has more effects on the development of quantitative retrieval products, and influenced by multiple factors, including the radiative transfer model and its parameter configurations, as well as atmospheric profile characteristics. Here, more details are provided as follows.

Firstly, a number of radiative transfer models are available for simulating brightness temperatures on different microwave frequencies, which can generally be classified into two main categories: fast radiative transfer models and line-by-line ones. Models, such as the Community Radiative Transfer Model (CRTM), the Radiative Transfer for TIROS Operational Vertical Sounder (RTTOV), and the ARTS, are capable of reproducing observed brightness temperatures within approximately 1 K over the 183 GHz frequency band under clear-sky conditions [

1]. However, for BT simulations under cloudy-sky conditions, line-by-line models achieve higher accuracy and are, therefore, often used as benchmarks for evaluating the performance of fast radiative transfer models [

2]. Thus, the selection of radiative transfer models is typically determined by the specific objectives of the study. Fast radiative transfer models are generally employed when large volumes of simulations are required, whereas line-by-line models are preferred when higher accuracy in the simulated brightness temperatures is prioritized.

Secondly, regarding the choice of atmospheric profiles, most studies typically relied on data generated by numerical weather prediction (NWP) models or observational products obtained from spaceborne payloads. Atmospheric data from NWP models are characterized by continuous temporal and broad spatial coverages. However, when simulating brightness temperatures under cloudy-sky conditions, the error budget of model–observation comparisons is largely dominated by the limited predictability of clouds and precipitation at small spatial scales in NWP models, which leads to root-mean-square (RMS) differences of 20–40 K in brightness temperatures due to the imperfect representation of cloud and precipitation structure, including their shape, size, and intensity [

3]. Therefore, for high-accuracy BT simulations in cloudy-sky conditions, it is preferable to use spatially collocated observational data from satellite instruments as input, which offer better spatial representativeness compared with those from NWP models.

Furthermore, in high-accuracy BT simulations of cloudy scenes, the selection of ice particle models and its particle size distributions (PSDs) is often challenging. Under varying ice amount conditions, the ice particle model is most dominant factor contributor to the discrepancies between simulated and observed brightness temperatures [

4]. Different ice habits exhibit significantly distinct microwave scattering properties, yet there is currently no reliable method to directly infer ice habit from microwave observations [

5]. Therefore, this study primarily focuses on the selection of optimal ice particle models to ensure the accuracy of cloudy-sky BT simulations at the 183 GHz frequency band.

Many studies have investigated the selection of ice particle models and proposed some helpful references for subsequent research. Previous studies have demonstrated that non-spherical ice particle models generally produce more accurate simulation results than spherical models [

6]. Moreover, some studies have evaluated and recommended specific ice particle models. The sector snowflake model [

7] was recommended for BT simulations across the 10–183 GHz frequency range [

3]. The block hexagonal column model [

7] was suggested for 183 GHz simulations over tropical regions [

8]. The dendrite model [

7] was proposed for BT simulations at the 183 ± 3.0 GHz and 183 ± 7.0 GHz channels [

9]. However, the above-mentioned studies did not distinguish among different cloud types, which is theoretically insufficient for achieving high-accuracy BT simulations in cloudy-sky conditions. In addition, Geer [

10] classified cloudy scenes and recommended specific ice particle models for cloud ice, large-scale snow, and convective snow, the conclusions were derived using atmospheric profiles from NWP models as input. Particularly, Wu, et al. [

4] employed CloudSat observations to recommend ice particle models for clouds with different ice water path (IWP) values. However, their ice particle models for each cloud type were based on weighted results from four channels (166 H, 166 V, 183.31 ± 7 V, and 183.31 ± 3 V, all in GHz), lacking detailed analysis of more 183 GHz channels with different weighting-function peak altitudes.

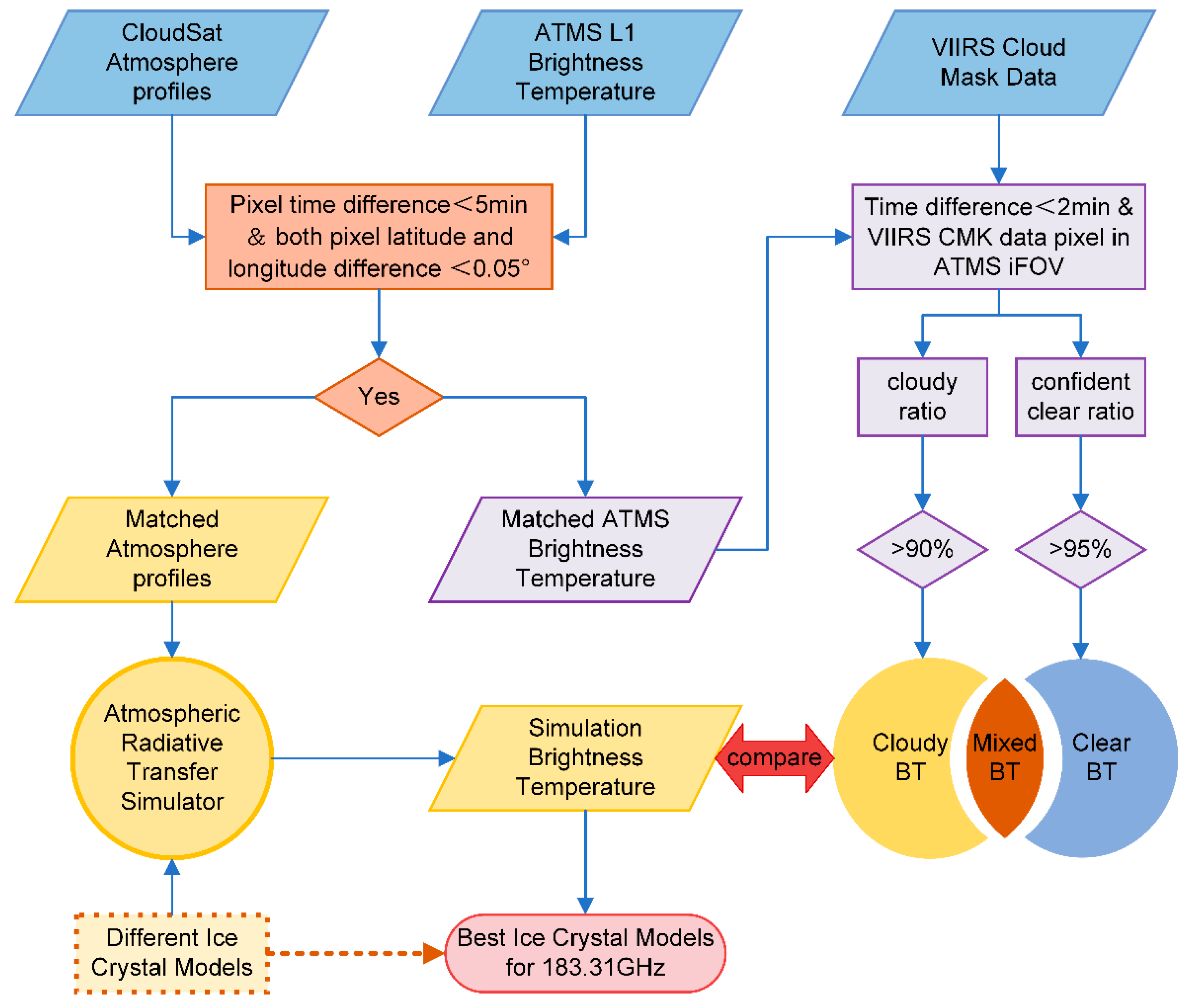

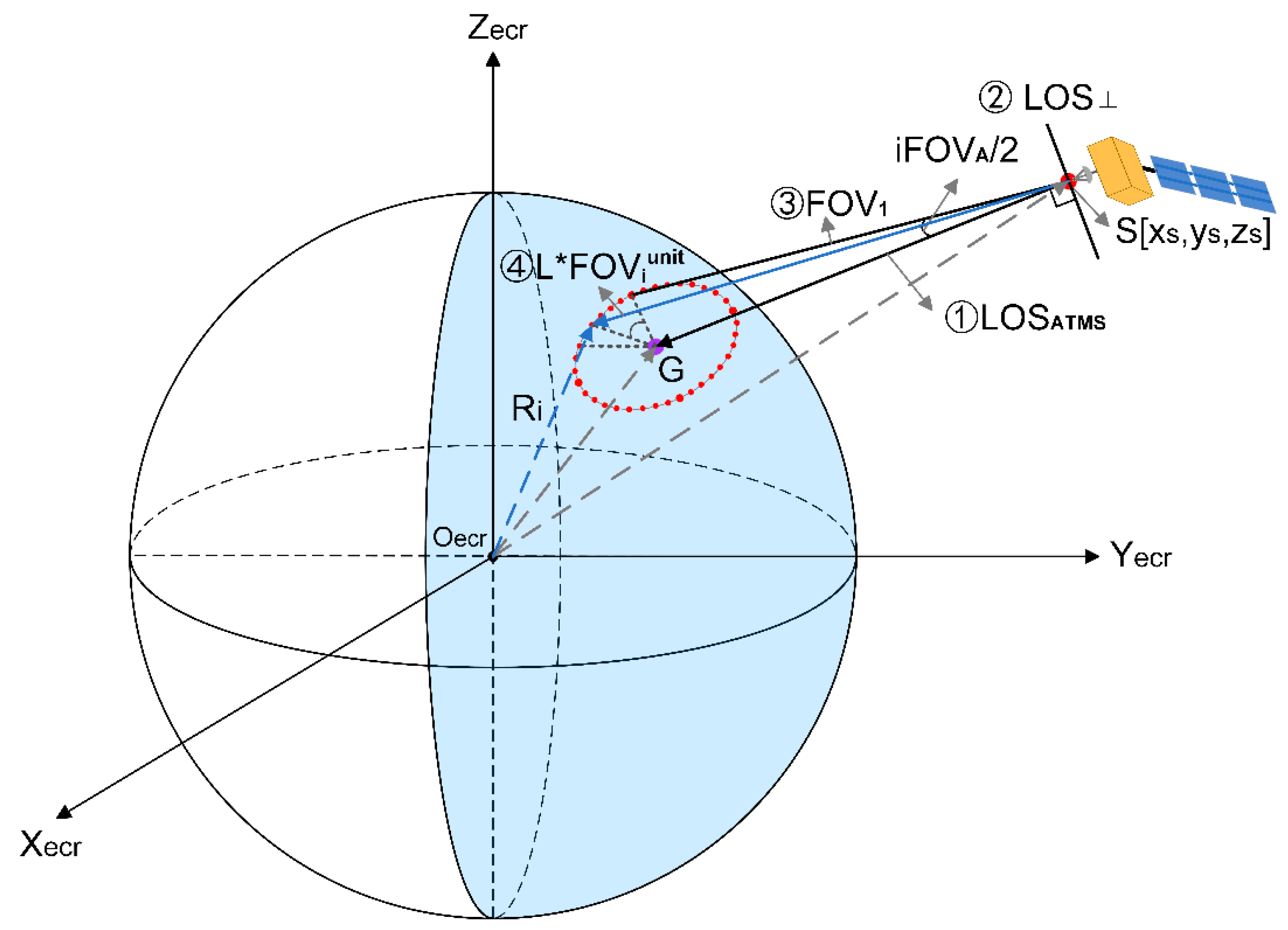

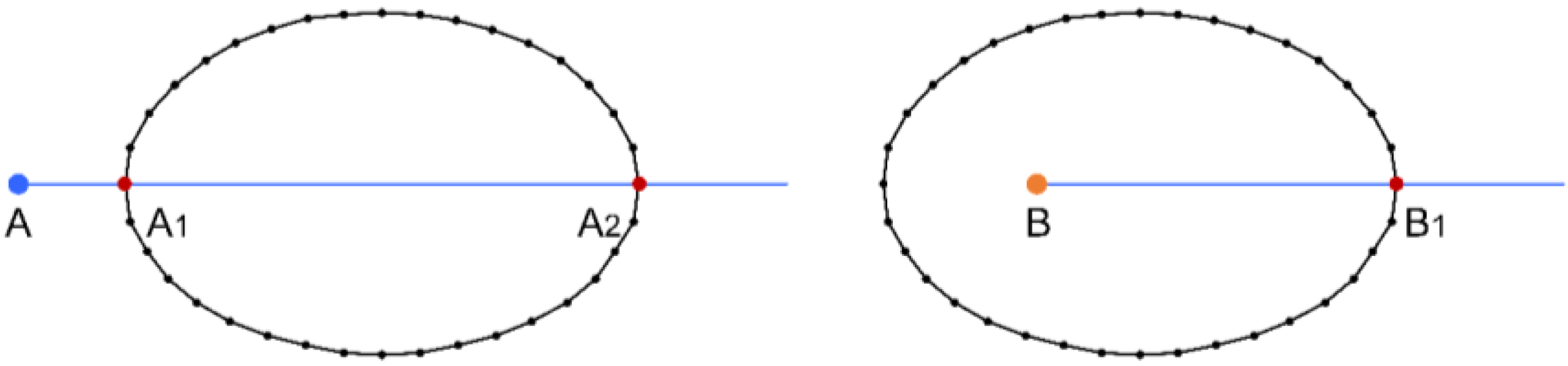

Therefore, to better meet the requirements of simulating 183 GHz satellite observations under cloudy-sky conditions, and to more robustly identify the most suitable ice particle models for different cloud types, more refined radiative transfer simulations are required. To achieve this objective, measurements from the active CPR onboard CloudSat satellite are selected to represent realistic atmospheric profiles under cloudy-sky conditions. The high-precision radiative transfer simulation model ARTS is adopted to simulate brightness temperatures at 183 GHz for the rigorously collocated Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder (ATMS) samples. By comparing simulated and observed brightness temperatures, the optimal ice particle model for the seven types of clouds individually is evaluated and further identified. Considering that the brightness temperatures observed by ATMS are strongly related to both the distribution and the extent of cloud coverage within their instantaneous field of views (iFOV), while the footprint of CloudSat merely represents a small portion those of ATMS, an absolutely identified approach for clouds is proposed to ensure the representativeness of the acquired profiles from CloudSat. Moreover, ATMS samples corresponding to those with as spatially uniform as possible for cloud coverage are selected for comparison between simulated and observed brightness temperatures. The overall technical workflow of this study is illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Simulated Brightness Temperatures Between ARTS and RTTOV in January

As a line-by-line radiative transfer model, the reliability of ARTS has been validated in numerous intercomparison studies [

1,

29,

30]. Moreover, Barlakas, et al. [

2] used ARTS as a reference model for cross-validation against RTTOV-SCATT. This work also performed a comparison between ARTS and the fast radiative transfer model RTTOV for BT simulations at the 183 GHz channels, using the sample data from January 2016. Both models used the same configuration of atmospheric profiles, ice particle models, and particle size distributions: the 6BR model with the F07 PSD for ice and the Liquid Sphere model with the MGD for liquid water. The ocean surface emissivity in both models was computed using TESSEM2 [

21]. Since the main aim of this comparison was to evaluate the computational accuracy differences between a line-by-line and a fast radiative transfer model, no further comparisons between different ice particle models were performed.

As shown in

Figure 6, under clear-sky conditions, both ARTS and RTTOV exhibit small mean bias errors (MBEs) between the simulated and observed brightness temperatures at the 183.31 ± 7.0, 183.31 ± 4.5, 183.31 ± 3.0, 183.31 ± 1.8, and 183.31 ± 1.0 GHz channels. Except for a slightly larger bias exceeding 1 K in the 183.31 ± 7.0 GHz channel for RTTOV, the MBEs of both models remain below 1 K for all other channels. Moreover, the narrow confidence intervals of these biases indicate that both the fast radiative transfer model and the line-by-line model achieve comparable accuracy and reliability in simulating brightness temperatures under clear-sky conditions.

Under cloudy-sky conditions, the ARTS simulations also show high accuracy, with MBEs between simulated and observed brightness temperatures remaining below 1 K across all five 183.31 GHz channels. The corresponding confidence intervals are likewise narrow, indicating stable and consistent performance. In comparison, the RTTOV simulations exhibit wider confidence intervals at all five channels and significantly. Therefore, the use of the line-by-line radiative transfer model ARTS for the selection of ice particle models is reasonable and reliable.

3.2. Comparison of Simulated Brightness Temperatures Between Clear-Sky and Cloudy-Sky Conditions

As shown in

Figure 7, the bias distributions between the simulated and observed brightness temperatures exhibit distinct characteristics under clear-sky and cloudy-sky conditions across the four analyzed months of 2016. The clear-sky bias distributions are generally narrow and approximately symmetric, whereas the cloudy-sky biases display broader spreads and more complex distributional characteristics, reflecting the increased uncertainties associated with cloud microphysical properties and their representation in the simulations.

As illustrated in

Figure 8, for all four analyzed months in 2016, the root mean square errors (RMSEs) of the simulated brightness temperatures under clear-sky conditions are smaller than those under cloudy-sky conditions at all five 183.31 GHz channels. The correlation between the simulated and observed brightness temperatures is likewise stronger for the clear-sky samples than for the cloudy ones. The relatively larger uncertainties in the cloudy-sky simulations can primarily be attributed to uncertainties in the representation of LWC, IWC, PSDs, and hydrometeor models within the atmospheric profiles. In addition, the mean absolute errors (MAEs) of the clear-sky simulations remain below 1 K, and the corresponding coefficients of determination (R

2) exceed 0.95 for all four months, indicating that the clear-sky simulations overall perform very well. These results suggest that the biases in cloudy-sky simulations are largely independent of those in clear-sky simulations and are instead primarily controlled by parameters such as the ice particle model, thereby providing a physically robust basis for further analysis of cloud microphysical properties in the atmosphere.

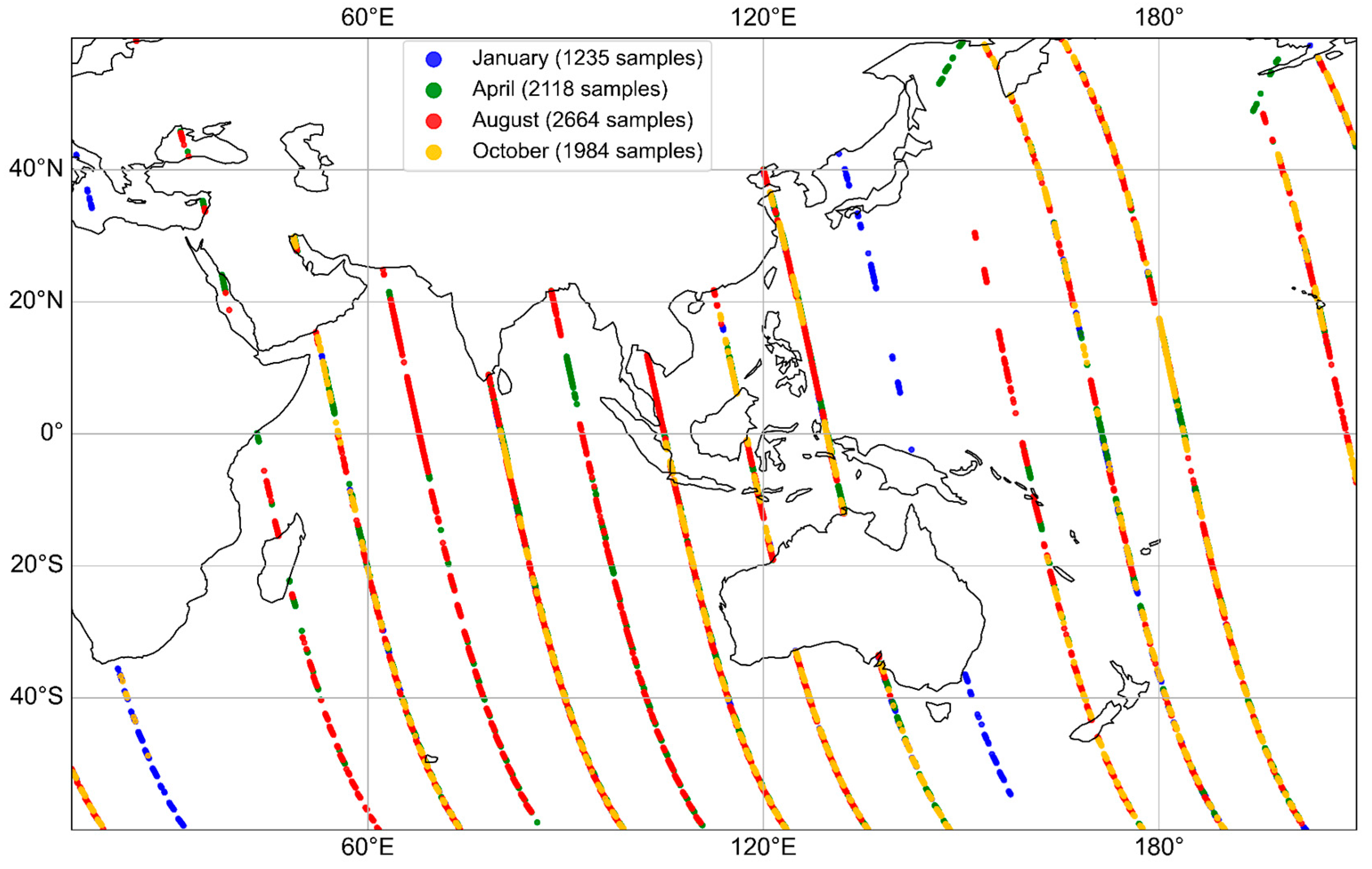

3.3. Selection of Optimal Ice Particle Models for Different Cloud Types

In total, 65,815 CloudSat atmospheric profiles were collocated with 8181 fully cloudy ATMS samples from the four analyzed months in 2016, corresponding to an average of approximately eight CloudSat profiles within each ATMS iFOV. When all coincident CloudSat profiles within an ATMS iFOV contained a single cloud layer of the same cloud type, the corresponding ATMS footprint was classified as representing that specific cloud type. After applying this selection criterion, 2938 fully cloudy ATMS samples met the requirements and were used to identify the optimal ice particle models. The sample size for each cloud type is listed in

Table 6. The spatial distribution of these cloud samples is shown in

Figure 9. Stratus clouds were excluded from the statistical analysis because of their limited number, as they are often difficult to distinguish from stratocumulus in the 2B-CLDCLASS-LIDAR product.

For cirrus (Ci) clouds, which are located at high altitudes and are optically thin, ice-phase, and non-precipitating in nature, the hydrometeors are primarily composed of ice crystals. As shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, when the spherical ice particle model SS1 is used, the root mean square error (RMSE) between the simulated and observed brightness temperatures reaches 4.88 K at the channel corresponding to the lowest peak of the weighting function. In contrast, using seven representative non-spherical ice particle models, including 6BR, CT1, SS2, SBA, SPA, LCA, and LPA, reduces the RMSE at the same channel to around 1.8 K, representing an improvement of approximately 3 K relative to the spherical case. These non-spherical models also produce smaller errors across the remaining four 183 GHz channels. Therefore, for Ci clouds composed entirely of ice crystals, adopting non-spherical ice particle models provides more accurate BT simulations than assuming sphericity. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 11, the differences in MBE among the various nonspherical ice particle models are less than 1 K, and the confidence intervals exhibit approximately identical widths across all channels. The differences among these non-spherical models are comparatively minor for thin Ci, probably because the influence of particle shape on total extinction becomes less pronounced when the ice water path (IWP) is low. Consequently, any of these non-spherical models can be reasonably applied for simulating the brightness temperatures of Ci clouds.

Altostratus (As) is a midlevel mixed-phase cloud whose hydrometeors typically contain both ice crystals and liquid droplets. As shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, the spherical ice particle model (SS1) performs substantially worse than the non-spherical models. At the 183.31 ± 7.0 GHz channel, the RMSE of the spherical model reaches 22.28 K, whereas the smallest RMSE among the non-spherical models is only 2.41 K. Even at the 183.31 ± 1.0 GHz channel, the minimum RMSE of the non-spherical models remains about 3 K lower than that of SS1. In contrast to the results for Ci, the differences among the non-spherical models for As are more evident. This can be attributed to the generally higher IWP of As clouds, since a larger IWP amplifies the cumulative differences in bulk optical properties across different particle habits. For As, the SBA and LCA models yield smaller RMSEs, all below 2.5 K at the 183.31 ± 7.0 GHz channel. The corresponding MBEs for SBA and LCA are also small, and their confidence intervals are correspondingly narrower. Therefore, the SBA and LCA models are recommended for BT simulations of As clouds.

Altocumulus (Ac), Stratocumulus (Sc), and Cumulus (Cu) clouds are predominantly liquid phase clouds, although ice crystals may occasionally be present. As illustrated in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, the RMSEs of the simulated brightness temperatures obtained using different ice particle models are all below 3 K, and the differences between the spherical and non-spherical models are generally minor. Moreover, for the Ac, Sc, and Cu cloud types, the MBEs of all ice particle models remain below 2 K, and the confidence intervals exhibit comparable widths. This can be attributed to the relatively low IWP in these clouds, as the bulk extinction is primarily governed by LWC. Therefore, a variety of ice particle models can be appropriately applied to simulate the observed brightness temperatures of liquid phase clouds such as Ac, Sc, and Cu.

Nimbostratus (Ns) is a thick, precipitating midlevel cloud composed of both ice crystals and liquid droplets, typically with a high IWP. For Ns, the non-spherical ice particle models yield more accurate BT simulations than the spherical model. At the 183.31 ± 7.0 GHz channel, the RMSE of the spherical model (SS1) reaches 14.31 K, whereas that of the SBA, SPA, and LCA models are below 2.5 K, corresponding to a difference of approximately 12 K. The absolute MBEs of the SBA, SPA, and LCA models are all less than 1 K, and their confidence intervals are of comparable width and narrower than those of the other models. Therefore, the SBA, SPA, and LCA models are recommended for BT simulations of Ns clouds across all five 183 GHz channels.

Deep convective (Dc) clouds are vertically developed convective systems composed of both ice crystals and liquid droplets, typically associated with large IWP. For such clouds, the non-spherical ice particle models yield significantly more accurate BT simulations than the spherical model. At the 183.31 ± 7.0 GHz channel, the SBA model reduces the RMSE by approximately 65 K compared with the spherical model, and even at the 183.31 ± 1.0 GHz channel, the RMSEs are still reduced by about 40 K. Because of the high IWP of Dc clouds, the differences among the various non-spherical models are also more pronounced. Across all channels, the SBA model exhibits the lowest RMSE values and the smallest absolute MBEs, and it also features the narrowest confidence intervals. Based on these comparison results, the SBA model is recommended for BT simulations of Dc clouds.

The recommended optimal ice particle models for different cloud types at the representative 183 GHz channels are summarized in

Table 7.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated and identified the optimal ice particle models for simulating observed brightness temperatures with respect to different cloud types at the 183 GHz frequency band. The comparison in

Section 3.3 indicates that, when applying the ice particle models recommended in

Table 5, the simulated brightness temperatures in the 183 GHz band achieve RMSE lower than 3 K for Ci, Ac, Sc, As, Cu, and Ns clouds. For Dc clouds, although the RMSE remains around 10 K, the adoption of the SBA model significantly reduces the simulation errors against those with the spherical model, while RMSE decreased by approximately 50 K. The BT simulations for Dc clouds still require further improvement in the future

The IWC data used in this study were obtained from the 2B-CWC-RO product, which classifies all hydrometeors at temperatures below −20 °C as ice-phase particles. This assumption neglects the presence of supercooled raindrops, which usually exists within deep convective systems [

31]. Moreover, the IWC in the 2B-CWC-RO product is generated with assumption of equivalent-mass homogeneous spherical ice particles, which is inconsistent with the actual shapes of ice crystals in the atmosphere. The aforementioned uncertainties may introduce larger discrepancies in the simulated brightness temperatures of Dc clouds. Consequently, a refined reconstruction of the IWC is planned as part of future research efforts.

In addition, this study does not include detailed comparisons among different PSDs, which will also be investigated future. Moreover, applying PSD that more accurately represent large ice particles in precipitating clouds [

32] and accounting for the orientation of hydrometeor particles in radiative transfer simulations [

33] will be important directions for future researches.

Subsequent research will utilize fast radiative transfer models to generate high-temporal-frequency simulations of brightness temperatures at 183 GHz, based on the ice particle models recommended in

Table 7.

5. Conclusions

The choice of ice particle models is a key factor influencing the accuracy of cloudy-sky BT simulations at 183 GHz. This study conducted a statistical evaluation of cloudy-sky BT simulations over the mid- to low-latitude oceans of the Eastern Hemisphere for four representative months.

Based on the comparative analysis of seven cloud types, they are classified into three primary categories according to their microphysical phases: ice clouds, mixed-phase clouds, and liquid-phase clouds. The main conclusions are summarized as follows.

(1) The sensitivity of simulated radiances in cloudy-sky conditions to ice particle habits varies across different cloud phases. For Ac, Sc, and Cu, which are mainly liquid-phase clouds, the influence of changing ice particle models on simulated brightness temperatures is relatively minor, with BT differences smaller than 1 K.

(2) For mixed-phase and ice clouds, which generally contain the higher fraction of ice particles compared with liquid-phase ones, the adoption of non-spherical ice particle models can significantly improve the accuracy of BT simulations at the 183 GHz frequency band against the conventional spherical assumption. For Ci clouds, any of the non-spherical models, including 6BR, SS2, CT1, SBA, SPA, LCA, and LPA, yields simulated brightness temperatures with RMSEs less than 2 K. The SBA and SPA models demonstrate good performance for As clouds, with RMSEs below 2.5 K, while the SBA, SPA, and LCA models exhibit similarly good performance for Ns clouds, also achieving RMSEs below 2.5 K. For Dc clouds, although the SBA model yields RMSEs of around 10 K, it still implements a substantial improvement over the spherical model.

(3) For the typical channels within the 183 GHz frequency band, the sensitivity of simulated brightness temperatures to ice particle models decreases as the weighting-function peak altitude increases. This may be attributed to the fact that channels with higher weighting-function peaks are less affected by surface-emitted radiation, resulting in smaller extinction differences among different ice particle models.

When performing cloudy-sky BT simulations at the 183 GHz frequency band, the findings of this study provide valuable references for selecting appropriate ice particle models for different cloud types and offer helpful supports for fast radiative transfer simulations of brightness temperatures for the Fengyun-4M microwave mission.