Satellite-Based Assessment of Marine Environmental Indicators and Their Variability in the South Pacific Island Regions: A National-Scale Perspective

Highlights

- Satellite products (sea surface temperature and salinity) showed generally agreement with in-situ data, and acceptable performance for Secchi disk depth, surface chlorophyll-a, net primary production, and sea level anomaly across 12 Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of the South Pacific Island Countries (SPICs).

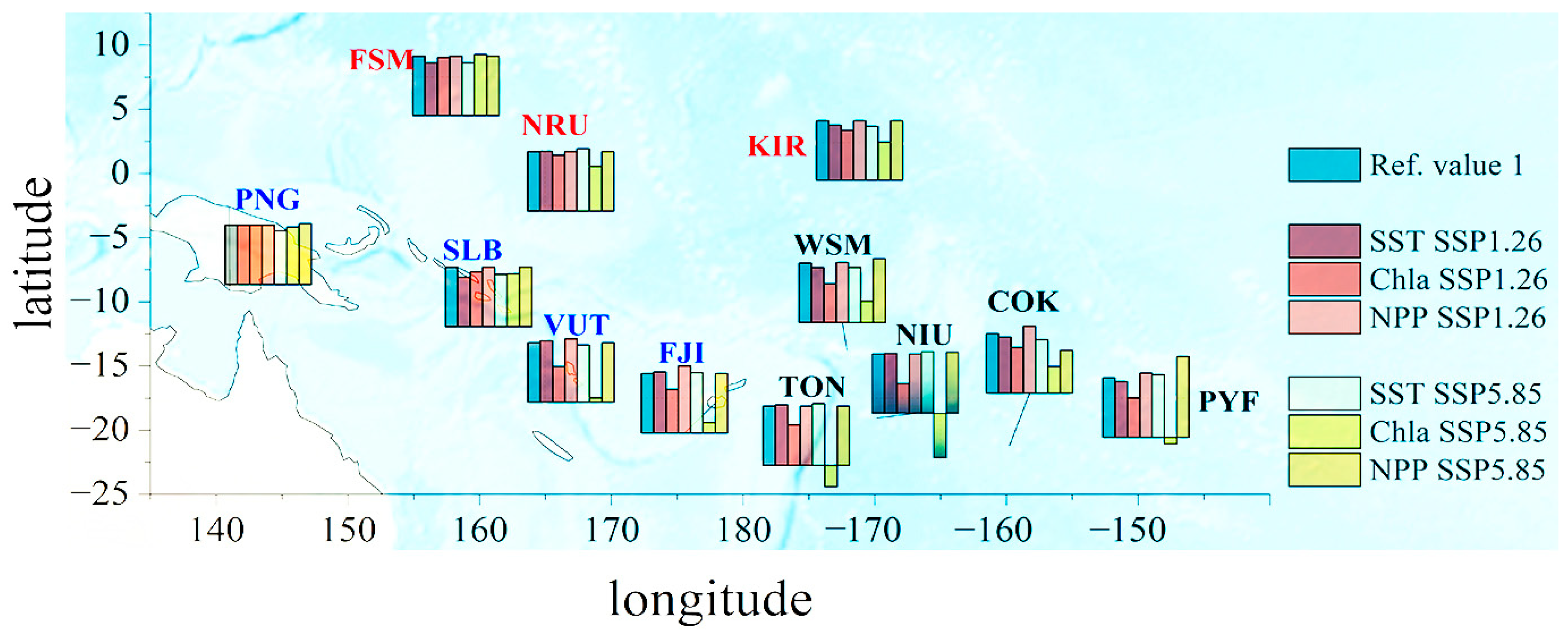

- During the past decades, satellite data revealed general rises in regional sea surface temperature and sea level, with marked within-EEZ-scale heterogeneity in inter-annual changing rates of chlorophyll-a and net primary production, underscoring the need for national-scale assessments.

- Satellite data could help constrain CMIP6 uncertainty, but it is subject to the accuracy.

- Southeastern EEZs exhibit sensitivity to satellite-based constraints, leading to pronounced changes in CMIP6 projections.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Used in Research

2.2.1. In Situ Data

2.2.2. Satellite and CMIP6 Data

2.3. Analysis Method

2.3.1. Statistical Parameters

2.3.2. Approach to Obtain the Changing Rates

2.3.3. Satellite-Based Statistical Downscaling Approach

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Performance of the Satellite-Derived Data in Research Areas

3.1.1. Match-Up Between Satellite and in Situ Data

3.1.2. Evaluation of Satellite-Derived Data

3.1.3. National-Scale Uncertainty Analyses

3.2. Variability of Marine Environment Indicators in EEZs

3.2.1. Climatological Intra-Annual Change

3.2.2. Inter-Annual Variability

3.3. Evaluation of the CMIP6-Projected Results on EEZs Scale

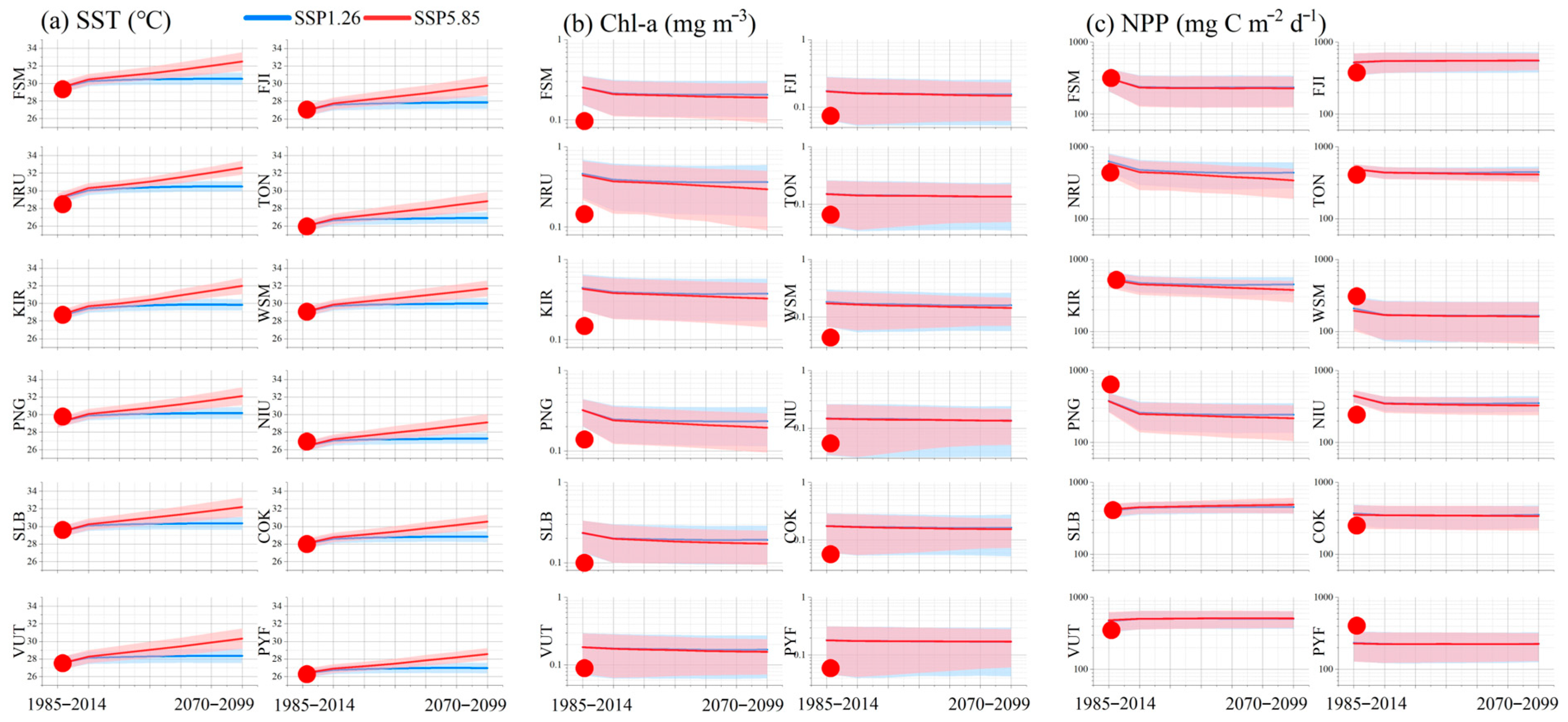

3.3.1. CMIP6-Projected Results

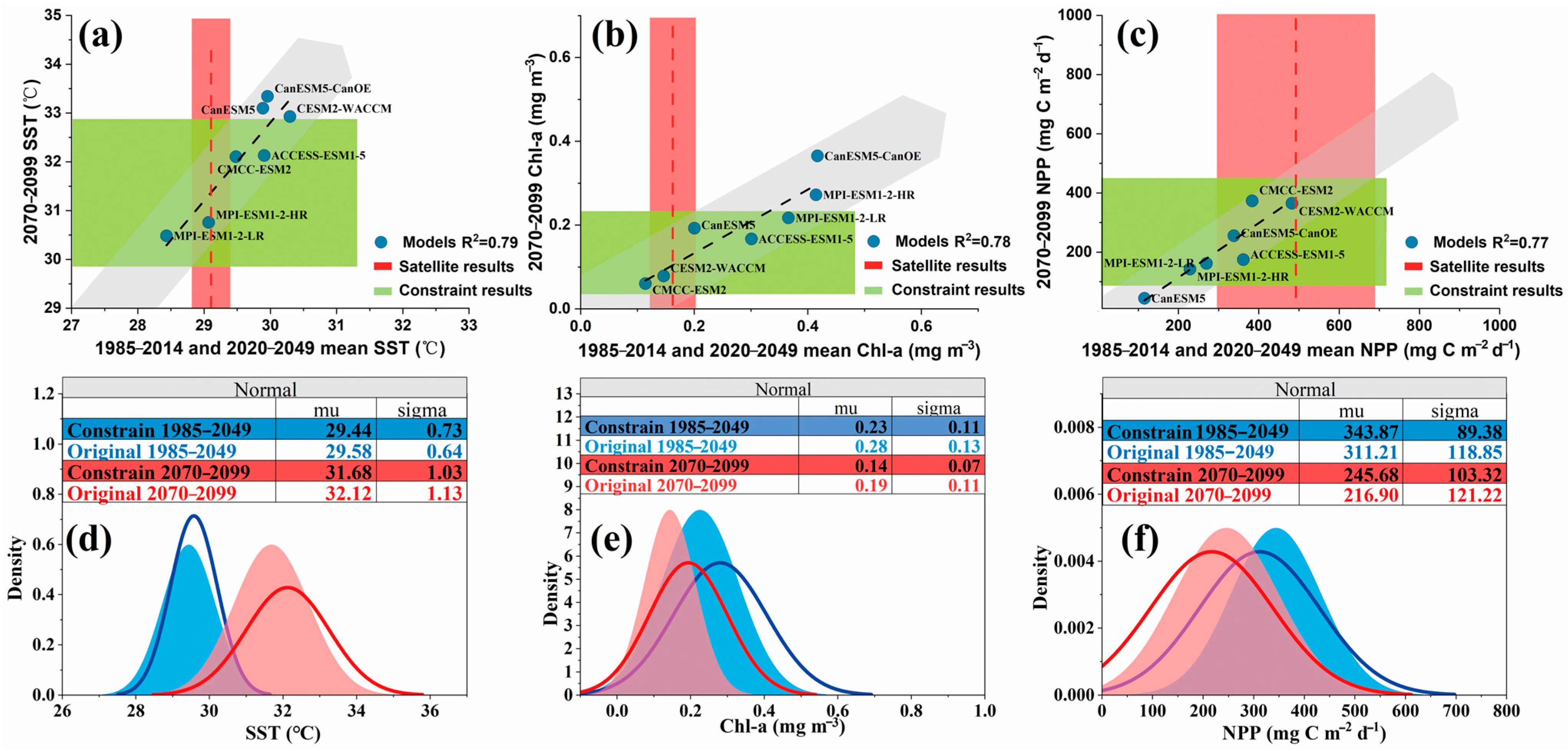

3.3.2. Re-Analysis of CMIP6 Projections with Satellite Results as Constraints

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Validation results support our confidence in using current satellite products (SST, SSS, SDD, Chl-a, NPP, and SLA) to conduct EEZ-scale assessments. Further investigation is required to assess their applicability at nearshore or community–ecosystem scales, where increased local optical complexity and dynamic processes may introduce greater uncertainties.

- (2)

- All 12 EEZs experienced seawater warming and sea-level rise, while Chl-a, NPP, SDD, and SSS exhibited within-EEZ heterogeneity. Among the study areas, Papua New Guinea exhibited the largest within-EEZ inter-annual variability across the analyzed indicators.

- (3)

- Satellite-derived data would help to constrain the uncertainty of CMIP6 model projections in the SPICs, subject to the accuracy of the satellite products. By 2100, Nauru EEZ is projected to be the most vulnerable, while French Polynesia is expected to maintain relatively stable oceanic conditions among all 12 EEZs. In contrast, significant changes are exhibited between unconstrained and constrained CMIP6 projections in the Southeastern EEZs.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Office of the UN Resident Coordinator. United Nations Pacific Strategy 2018–2022: A Multi-Country Sustainable Development Framework in the Pacific Region; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, R. Introduction to the South Pacific. In The South Pacific: Problems, Issues and Prospects; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1991; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, M.J.; Lyons, B.P.; Johnson, J.E.; Hills, J.M. The tropical Pacific Oceanscape: Current issues, solutions and future possibilities. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 166, 112181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.E.; Mimura, N. Vulnerability, Risk and Adaptation Assessment Methods in the Pacific Islands Region: Past approaches, and considerations for the future. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Marra, J.J.; Gooley, G.; Johnson, M.-V.V.; Keener, V.W.; Kruk, M.; McGree, S.; Potemra, J.T.; Warrick, O. Pacific Islands Climate Change Monitor: 2021. In The Pacific Islands-Regional Climate Centre (PI-RCC) Network Report to the Pacific Islands Climate Service (PICS) Panel and Pacific Meteorological Council (PMC); PI-RCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, J. Adapting to Climate Change in Pacific Island Countries: The Problem of Uncertainty. World Dev. 2001, 29, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. State of the Climate in the South-West Pacific; 1356; World Meteorological Organization (WMO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Keener, V.; Helweg, D.; Asam, S.; Balwani, S.; Burkett, M.; Fletcher, C.; Giambelluca, T.; Grecni, Z.; Nobrega-Olivera, M.; Polovina, J.; et al. Hawai’i and US-Affiliated Pacific Islands; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R. Global Warming of 1.5 °C; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- SPREP. SPREP Annual Report: 2023; 45826; Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP): Apia, Samoa, 2024; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, L.; Thomas, A. 1.5 To Stay Alive? AOSIS and the Long Term Temperature Goal in the Paris Agreement. Environ. Sci. Political Sci. 2016, 10, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, W.M. An introduction to the tropical Pacific and types of Pacific Islands. In The Geography, Nature and History of the Tropical Pacific and Its Islands; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- McGree, S.; Smith, G.; Chandler, E.; Harold, N.; Begg, Z.; Kuleshov, Y.; Malsale, P.; Ritman, M. Climate Change in the Pacific 2022: Historical and Recent Variability, Extremes and Change; Pacific Community (SPC): Suva, Fiji, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dhage, L.; Widlansky, M.J. Assessment of 21st Century Changing Sea Surface Temperature, Rainfall, and Sea Surface Height Patterns in the Tropical Pacific Islands Using CMIP6 Greenhouse Warming Projections. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keener, V.W.; Grecni, Z.N.; Moser, S.C. Accelerating Climate Change Adaptive Capacity Through Regional Sustained Assessment and Evaluation in Hawai‘i and the U.S. Affiliated Pacific Islands. Front. Clim. 2022, 4, 869760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Ying, J.; Collins, M. Sources of Uncertainty in the Time of Emergence of Tropical Pacific Climate Change Signal: Role of Internal Variability. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 2535–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, R.C.J.; Dong, Y.; Proistosecu, C.; Armour, K.C.; Battisti, D.S. Systematic Climate Model Biases in the Large-Scale Patterns of Recent Sea-Surface Temperature and Sea-Level Pressure Change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabue, A.; Kwiatkowski, L.; Bopp, L.; Butenschön, M.; Cheung, W.; Lengaigne, M.; Vialard, J. Persistent Uncertainties in Ocean Net Primary Production Climate Change Projections at Regional Scales Raise Challenges for Assessing Impacts on Ecosystem Services. Front. Clim. 2021, 3, 738224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, L.; Bopp, L.; Aumont, O.; Ciais, P.; Cox, P.M.; Laufkötter, C.; Li, Y.; Séférian, R. Emergent constraints on projections of declining primary production in the tropical oceans. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.P.; Belmadani, A.; Menkes, C.; Stephenson, T.; Thatcher, M.; Gibson, P.B.; Peltier, A. Higher-resolution projections needed for small island climates. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 668–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, M.; Ghorbanian, A.; Asgarimehr, M.; Yekkehkhany, B.; Moghimi, A.; Jin, S.; Naboureh, A.; Mohseni, F.; Mahdavi, S.; Layegh, N.F. Remote Sensing Systems for Ocean: A Review (Part 1: Passive Systems). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Chen, X.; Li, T.; Gong, F. Long-Term Changes in the Land–Ocean Ecological Environment in Small Island Countries in the South Pacific: A Fiji Vision. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhou, C.; Shao, Q.; Mulla, D.J. Remote sensing of sea surface temperature and chlorophyll-a: Implications for squid fisheries in the north-west Pacific Ocean. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 4515–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.; Chang, Y.; Lee, M.; Wu, R.-F.; Hsiao, S. Predicting Skipjack Tuna Fishing Grounds in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean Based on High-Spatial-Temporal-Resolution Satellite Data. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrack, L.; Wiggins, C.; Marra, J.J.; Genz, A.; Most, R.; Falinski, K.; Conklin, E. Assessing the spatial–temporal response of groundwater-fed anchialine ecosystems to sea-level rise for coastal zone management. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2021, 31, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Timmermann, A.; Lee, S.-S.; Schloesser, F. Rainfall and Salinity Effects on Future Pacific Climate Change. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2022EF003457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Song, Z.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Yu, S.; Zhang, S.; Gong, F. Remote sensing of global sea surface pH based on massive underway data and machine learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Liu, C.; Banzon, V.; Freeman, E.; Graham, G.; Hankins, B.; Smith, T.; Zhang, H.-M. Improvements of the Daily Optimum Interpolation Sea Surface Temperature (DOISST) Version 2.1. J. Clim. 2021, 34, 2923–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortreux, C.; Jarillo, S.; Barnett, J.; Waters, E. Climate change and migration from atolls? No evidence yet. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 60, 101234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOCCG. Uncertainties in Ocean Colour Remote Sensing; International Ocean Colour Coordinating Group (IOCCG): Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2019; p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, M.; Begg, Z.; Smith, G.; Miles, E. Lessons From the Pacific Ocean Portal: Building Pacific Island Capacity to Interpret, Apply, and Communicate Ocean Information. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; Fox, H.E.; Allen, G.R.; Davidson, N.; Ferdaña, Z.A.; Finlayson, M.; Halpern, B.S.; Jorge, M.A.; Lombana, A.; Lourie, S.A.; et al. Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas. BioScience 2007, 57, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Sathyendranath, S.; Brotas, V.; Groom, S.; Grant, M.; Taberner, M.; Antoine, D.; Arnone, R.; Balch, W.M.; Barker, K. A compilation of global bio-optical in situ data for ocean-colour satellite applications–version two. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1037–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, D.M.; Letelier, R.M.; Bidigare, R.R.; Björkman, K.M.; Church, M.J.; Dore, J.E.; White, A.E. Seasonal-to-decadal scale variability in primary production and particulate matter export at Station ALOHA. Prog. Oceanogr. 2021, 195, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADB. Sea-Level Change in the Pacific Islands Region: A Review of Evidence to Inform Asian Development Bank Guidance on Selecting Sea-Level Projections for Climate Risk and Adaptation Assessments; ADB: Manila, Philippines, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, J.; Moore, T.; Goyet, S.; Singh, A.; Brodie, G.; Pringle, P.; Seuseu, S.; Straza, T.; Buckley, P.; Townhill, B.; et al. Pacific Marine Climate Change Report Card December 2018; Commonwealth Marine Economies Programme; UK’s Centre for Environment: Wallingford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Pan, D.; Bai, Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, C.-T.A.; Zhu, Q.; Hao, Z.; Gong, F. Recent changes of global ocean transparency observed by SeaWiFS. Cont. Shelf Res. 2017, 143, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Gong, F.; Li, T. A new merged dataset of global ocean chlorophyll-a concentration for better trend detection. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1051619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M.J.; Falkowski, P.G. Photosynthetic rates derived from satellite-based chlorophyll concentration. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1997, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Cai, W.-J.; Chen, J.; Kirchman, D.; Wang, B.; Fan, W.; Huang, D. Climate and Human-Driven Variability of Summer Hypoxia on a Large River-Dominated Shelf as Revealed by a Hypoxia Index. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 634184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroux, M.-D.; Bonnardot, F.; Somot, S.; Alias, A.; Kotomangazafy, S.; Ridhoine, A.-O.S.; Veerabadren, P.; Amélie, V. Advancing climate services for vulnerable islands in the Southwest Indian Ocean: A combined approach of statistical and dynamical Cmip6 downscaling. Clim. Serv. 2024, 34, 100491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brient, F. Reducing Uncertainties in Climate Projections with Emergent Constraints: Concepts, Examples and Prospects. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 37, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Cox, P.; Huntingford, C.; Klein, S. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarska, K.B.; Stolpe, M.B.; Sippel, S.; Fischer, E.M.; Smith, C.J.; Lehner, F.; Knutti, R. Past warming trend constrains future warming in CMIP6 models. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz9549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.W.; Werdell, P.J. A multi-sensor approach for the on-orbit validation of ocean color satellite data products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 102, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Franz, B.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Sayer, A.M. Estimating pixel-level uncertainty in ocean color retrievals from MODIS. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 31415–31438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Zhou, W.; Wang, G.; Cao, W.; Xu, Z.; Liu, H.; Wu, G.; Zhao, W. Comparison of satellite-derived phytoplankton size classes using in-situ measurements in the South China Sea. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeau-Patissier, D.; Gower, J.F.R.; Dekker, A.G.; Phinn, S.R.; Brando, V.E. A review of ocean color remote sensing methods and statistical techniques for the detection, mapping and analysis of phytoplankton blooms in coastal and open oceans. Prog. Oceanogr. 2014, 123, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.K.; Gordon, H.R.; Voss, K.J.; Ge, Y.; Broenkow, W.; Treess, C. Validation of atmospheric correction over the oceans. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1997, 102, 17209–17217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibordi, G.; Holben, B.; Slutsker, I.; Giles, D.; D’Alimonte, D.; Mélin, F.; Berthon, J.F.; Vandemark, D.; Feng, H.; Schuster, G.; et al. AERONET-OC: A network for the validation of ocean color primary products. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2009, 26, 1634–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza, A.; Hilly, J.; Kay, M.; Prasad, A.; Dansie, A. Atmospheric aerosols in the South Pacific: A regional baseline and characterization of aerosol fractions. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 346, 121048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Lee, Z.; Shang, S. A system to measure the data quality of spectral remote-sensing reflectance of aquatic environments. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 8189–8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mélin, F.; Sclep, G.; Jackson, T.; Sathyendranath, S. Uncertainty estimates of remote sensing reflectance derived from comparison of ocean color satellite data sets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 177, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Feng, L.; Lee, Z. Uncertainties of SeaWiFS and MODIS remote sensing reflectance: Implications from clear water measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 133, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J.E.; Werdell, P.J. Chlorophyll algorithms for ocean color sensors—OC4, OC5 & OC6. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 229, 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, A.; Prieur, L. Analysis of variations in ocean color. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan, N.; Smith, B.; Schalles, J.; Binding, C.; Cao, Z.; Ma, R.; Alikas, K.; Kangro, K.; Gurlin, D.; Hà, N.; et al. Seamless retrievals of chlorophyll-a from Sentinel-2 (MSI) and Sentinel-3 (OLCI) in inland and coastal waters: A machine-learning approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 240, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z.; Hu, C.; Casey, B.; Shang, S.; Dierssen, H.; Arnone, R. Global shallow-water bathymetry from satellite ocean color data. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2010, 91, 429–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOCCG. Remote Sensing of Ocean Colour in Coastal, and Other Optically-Complex, Waters; Reports of the International Ocean-Colour Coordinating Group; IOCCG: Dartmouth, NS, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, A.G.; Phinn, S.R.; Anstee, J.; Bissett, P.; Brando, V.E.; Casey, B.; Fearns, P.; Hedley, J.; Klonowski, W.; Lee, Z.P.; et al. Intercomparison of shallow water bathymetry, hydro-optics, and benthos mapping techniques in Australian and Caribbean coastal environments. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2011, 9, 396–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurin, D.A.; Dierssen, H.M. Advantages and limitations of ocean color remote sensing in CDOM-dominated, mineral-rich coastal and estuarine waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 125, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.; Hu, C.; Cannizzaro, J.; English, D.; Muller-Karger, F.; Lee, Z. Evaluation of chlorophyll-a remote sensing algorithms for an optically complex estuary. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 129, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupouy, C.; Neveux, J.; Ouillon, S.; Frouin, R.; Murakami, H.; Hochard, S.; Dirberg, G. Inherent optical properties and satellite retrieval of chlorophyll concentration in the lagoon and open ocean waters of New Caledonia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 61, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupouy, C.; Tan, J.; Frouin, R.; Whiteside, A.; Singh, A.; Rodier, M.; Röttgers, R.; Oursel, B.; Murakami, H.; Goutx, M. Evaluating the applicability of ocean color algorithms in the Fiji region from in situ bio-optical data. In Proceedings of the SPIE Asia-Pacific Remote Sensing, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 3 January 2025; Volume 13264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupouy, C.; Whiteside, A.; Tan, J.; Wattelez, G.; Murakami, H.; Andréoli, R.; Lefèvre, J.; Röttgers, R.; Singh, A.; Frouin, R. A Review of Ocean Color Algorithms to Detect Trichodesmium Oceanic Blooms and Quantify Chlorophyll Concentration in Shallow Coral Lagoons of South Pacific Archipelagos. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubac, B.; Burvingt, O.; Nicolae Lerma, A.; Sénéchal, N. Performance and Uncertainty of Satellite-Derived Bathymetry Empirical Approaches in an Energetic Coastal Environment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPREP. State of Environment and Conservation in the Pacific Islands: 2020 Regional Report; Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP): Apia, Samoa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, T.; Butenschön, M.; Peck, M.A. Statistically downscaled CMIP6 ocean variables for European waters. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan-Keogh, T.J.; Tagliabue, A.; Thomalla, S.J. Global decline in net primary production underestimated by climate models. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooya, P.; Swart, N.C.; Hamme, R.C. Time-varying changes and uncertainties in the CMIP6 ocean carbon sink from global to local scale. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2023, 14, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlunegger, S.; Rodgers, K.B.; Sarmiento, J.L.; Ilyina, T.; Dunne, J.P.; Takano, Y.; Christian, J.R.; Long, M.C.; Frölicher, T.L.; Slater, R.; et al. Time of Emergence and Large Ensemble Intercomparison for Ocean Biogeochemical Trends. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2020, 34, e2019GB006453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravatte, S.; Delcroix, T.; Zhang, D.; McPhaden, M.; Leloup, J. Observed freshening and warming of the western Pacific Warm Pool. Clim. Dyn. 2009, 33, 565–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen Gupta, A.; McGregor, S.; van Sebille, E.; Ganachaud, A.; Brown, J.N.; Santoso, A. Future changes to the Indonesian Throughflow and Pacific circulation: The differing role of wind and deep circulation changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 1669–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claustre, H.; Sciandra, A.; Vaulot, D. Introduction to the special section bio-optical and biogeochemical conditions in the South East Pacific in late 2004: The BIOSOPE program. Biogeosciences 2008, 5, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Alvarez, C.; González-Silvera, A.; Santamaría-del-Angel, E.; López-Calderón, J.; Godínez, V.M.; Sánchez-Velasco, L.; Hernández-Walls, R. Phytoplankton pigments and community structure in the northeastern tropical pacific using HPLC-CHEMTAX analysis. J. Oceanogr. 2020, 76, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp, L.; Resplandy, L.; Orr, J.C.; Doney, S.C.; Dunne, J.P.; Gehlen, M.; Halloran, P.; Heinze, C.; Ilyina, T.; Séférian, R.; et al. Multiple stressors of ocean ecosystems in the 21st century: Projections with CMIP5 models. Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 6225–6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal, W.; Xiang Chung, J.; Roseli, N.H.; Md Amin, R.; Mohd Akhir, M.F.B. Evaluation of CMIP6 model performance in simulating historical biogeochemistry across the southern South China Sea. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 4007–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, K.; Bertin, X.; Mengual, B.; Pezerat, M.; Lavaud, L.; Guérin, T.; Zhang, Y.J. Wave-induced mean currents and setup over barred and steep sandy beaches. Ocean Model. 2022, 179, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutheil, C.; Menkes, C.; Lengaigne, M.; Vialard, J.; Peltier, A.; Bador, M.; Petit, X. Fine-scale rainfall over New Caledonia under climate change. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 56, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandrich, K.M.; Timm, O.E.; Zhang, C.; Giambelluca, T.W. Dynamical Downscaling of Near-Term (2026–2035) Climate Variability and Change for the Main Hawaiian Islands. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2022, 127, e2021JD035684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter (Units) | SSS (psu) | SST (°C) | Chl-a (mg m−3) | SDD (m) | NPP (mg C m−2 d−1) | SLA (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | monthly | monthly | monthly | monthly | monthly | monthly |

| Spatial Resolution | 25 km | 4 km | 4 km | 4 km | 4 km | 0.25° |

| SSP1.26 | SSP5.85 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔSST (°C) | ΔChl-a (mg m−3) | ΔNPP (mg C m−2 d−1) | ΔSST (°C) | ΔChl-a (mg m−3) | ΔNPP (mg C m−2 d−1) | |

| FSM | 1.11 | −0.047 | −79.63 | 3.05 | −0.064 | −89.02 |

| NRU | 1.42 | −0.098 | −190.81 | 3.46 | −0.145 | −246.70 |

| KIR | 1.36 | −0.068 | −104.07 | 3.38 | −0.105 | −152.99 |

| PNG | 1.06 | −0.088 | −136.86 | 3.02 | −0.127 | −156.76 |

| SLB | 1.02 | −0.040 | 51.81 | 2.92 | −0.063 | 71.20 |

| VUT | 0.90 | −0.015 | 36.44 | 2.92 | −0.027 | 27.36 |

| FJI | 0.97 | −0.019 | 35.31 | 2.91 | −0.023 | 30.69 |

| TON | 0.98 | −0.016 | −43.04 | 2.91 | −0.014 | −78.86 |

| WSM | 1.02 | −0.023 | −42.61 | 2.71 | −0.028 | −33.38 |

| NIU | 0.94 | −0.012 | −90.07 | 2.78 | −0.012 | −119.62 |

| COK | 0.89 | −0.013 | −17.21 | 2.55 | −0.020 | −14.51 |

| PYF | 0.65 | −0.012 | −6.75 | 2.19 | −0.009 | −3.60 |

| SSP1.26 | SSP5.85 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔSST (°C) | ΔChl-a (mg m−3) | ΔNPP (mg C m−2 d−1) | ΔSST (°C) | ΔChl-a (mg m−3) | ΔNPP (mg C m−2 d−1) | |

| FSM | 0.99 | −0.046 | −79.63 # | 2.72 | −0.066 | −89.02 # |

| NRU | 1.43 | −0.092 | −190.81 # | 3.63 * | −0.109 | −246.70 # |

| KIR | 1.26 | −0.057 | −104.07 # | 3.06 | −0.067 | −152.99 # |

| PNG | 1.06 # | −0.088 | −136.73 | 2.74 | −0.123 | −160.64 |

| SLB | 0.85 | −0.037 | 51.81 # | 2.57 | −0.056 | 71.20 # |

| VUT | 0.93 | −0.009 | 38.91 | 2.81 | −0.002 | 27.36 # |

| FJI | 1.00 | −0.014 | 39.86 | 2.95 # | −0.004 | 30.69 # |

| TON | 1.00 * | −0.011 | −43.04 # | 3.03 * | 0.005 | −78.86 # |

| WSM | 0.94 * | −0.015 | −43.19 | 2.51 | −0.010 | −35.91 |

| NIU | 0.95 * | −0.006 | −90.07 # | 2.89 * | 0.009 | −122.63 |

| COK | 0.84 | −0.010 | −19.38 | 2.30 | −0.009 | −10.49 |

| PYF | 0.61 | −0.008 | −7.31 | 2.31 | 0.001 | −4.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, Q.; Li, T.; Bai, Y.; He, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Huang, X.; Huang, M.; Wang, D. Satellite-Based Assessment of Marine Environmental Indicators and Their Variability in the South Pacific Island Regions: A National-Scale Perspective. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010165

Hu Q, Li T, Bai Y, He X, Chen X, Chen L, Huang X, Huang M, Wang D. Satellite-Based Assessment of Marine Environmental Indicators and Their Variability in the South Pacific Island Regions: A National-Scale Perspective. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010165

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Qunfei, Teng Li, Yan Bai, Xianqiang He, Xueqian Chen, Liangyu Chen, Xiaochen Huang, Meng Huang, and Difeng Wang. 2026. "Satellite-Based Assessment of Marine Environmental Indicators and Their Variability in the South Pacific Island Regions: A National-Scale Perspective" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010165

APA StyleHu, Q., Li, T., Bai, Y., He, X., Chen, X., Chen, L., Huang, X., Huang, M., & Wang, D. (2026). Satellite-Based Assessment of Marine Environmental Indicators and Their Variability in the South Pacific Island Regions: A National-Scale Perspective. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010165