1. Introduction

Salt lakes are saline water bodies rich in mineral resources and play an important role in both industrial production and regional environmental systems [

1]. In salt lake regions, the distribution of saline surfaces is closely linked to mineral resource development and ecological monitoring. Among these surfaces, salt crusts are special high-salinity formations widely distributed around salt lakes. Different salt crust types often exhibit distinct salinity levels, which are closely associated with variations in subsurface brine concentration [

2]. In general, salt crusts with harder surfaces and higher roughness tend to correspond to higher brine salinity and are thus preferred zones for brine extraction in industrial salt production. Consequently, investigating the spatial distribution of salt crusts is of direct practical significance for both mineral resource exploitation and regional ecological environment monitoring in salt lake areas [

3].

Due to the vastness of the region and inconvenient transportation, traditional field survey methods are insufficient to obtain the distribution of salt crusts. With the continuous development of remote sensing technology, the application of remote sensing in environmental monitoring has attracted increasing attention [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Polarimetric synthetic aperture radar (PolSAR), with its all-weather and all-day observation capability, enables effective assessment of surface and near-surface material composition, morphology, and structural characteristics [

8,

9]. In addition, PolSAR could provide long-term time series data [

10,

11], making it possible to analyze temporal changes in salt crust regions. In combination with field investigations, therefore, this study aims to employ PolSAR-based land cover classification methods to examine the spatial distribution and temporal variations of different salt crust types in the salt lake region.

PolSAR image classification is a fundamental application of polarimetric SAR data, and its performance strongly depends on the effective representation of land-cover features. A wide range of polarimetric features have been developed based on raw polarimetric observations [

12,

13] and polarimetric decomposition theories [

14,

15,

16,

17], which have supported various unsupervised classification approaches such as Wishart-based methods [

18,

19]. In addition, machine learning models such as support vector machine (SVM) [

20] and random forest (RF) [

21] have also been applied to PolSAR image classification. However, most existing approaches rely on manually designed polarimetric features for pixel-wise classification [

22], which limits their ability to fully exploit the rich information contained in PolSAR data.

In recent years, deep learning has been increasingly applied to PolSAR image processing, enabling automatic feature extraction. Representative approaches include convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [

23], graph convolutional networks [

24], and self-attention mechanisms [

25]. Among them, CNNs have been widely used in PolSAR land-cover classification due to their strong capability in extracting local spatial features. Early studies explored CNN-based feature learning from polarimetric data [

26], and subsequent works further improved performance through complex-valued CNNs [

27], high-dimensional polarimetric inputs with adaptive feature selection [

28,

29], and refined network designs such as multi-path structures, residual connections, and manifold regularization [

30,

31,

32]. Despite these advances, CNNs mainly focus on local neighborhood modeling and are less effective in capturing long-range dependencies. To address this limitation, the Vision Transformer (ViT) was introduced in 2020 [

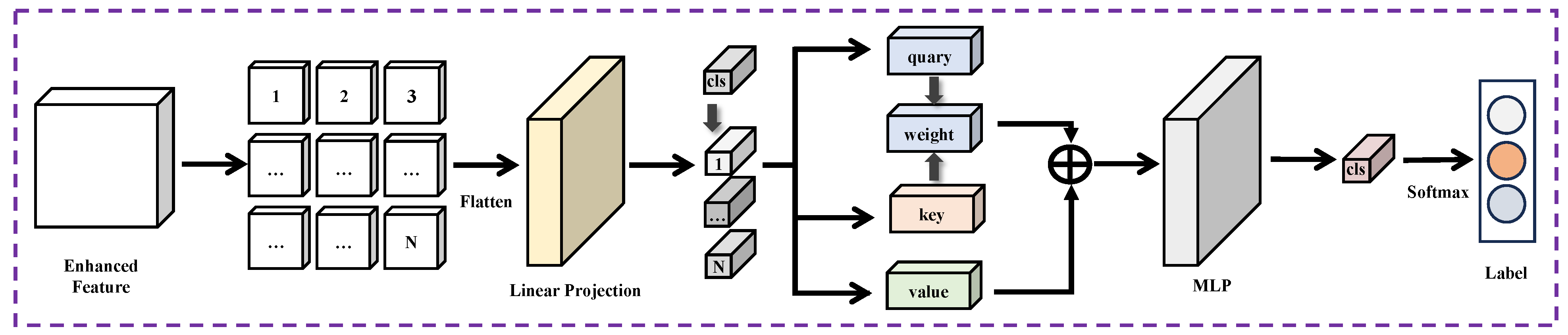

33,

34] and later applied to PolSAR classification by explicitly modeling global relationships among pixels [

35,

36,

37]. ViT-based frameworks have demonstrated improved global representation capability, while their sensitivity to local structures remains limited. To balance local and global feature modeling, several hybrid CNN–ViT architectures have been proposed, including frameworks that integrate three-dimensional (3D) and two-dimensional (2D) CNNs with local window attention (LWA) [

38], jointly model polarimetric coherency matrices across different polarization orientations using 3D convolution and self-attention [

39], or employ multi-scale context fusion strategies [

40]. Although these methods have achieved promising results, existing patch-level PolSAR classification approaches often rely on relatively simple fusion strategies, and the complementary strengths of CNNs in local texture perception and ViT in global context modeling have not yet been fully exploited.

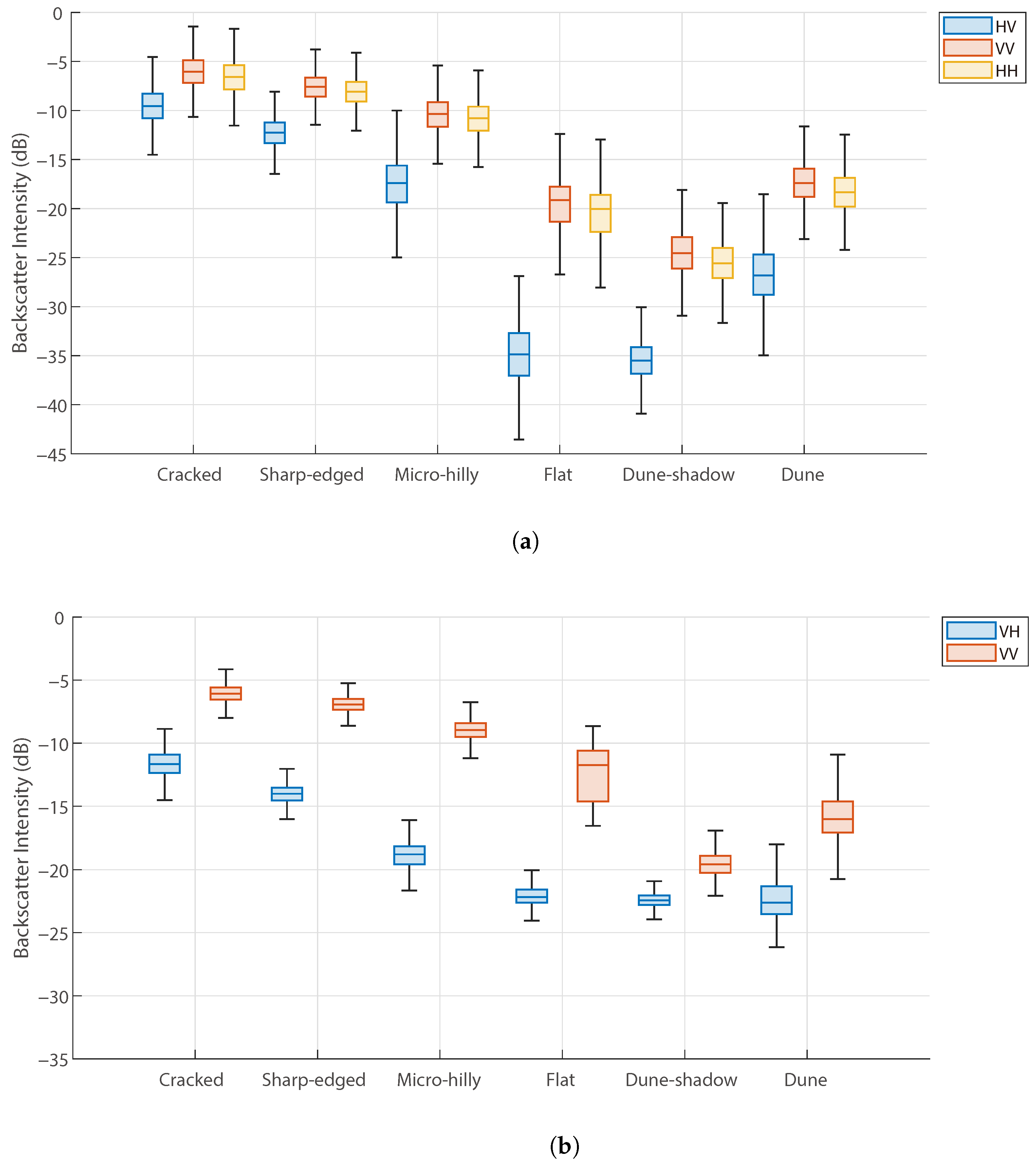

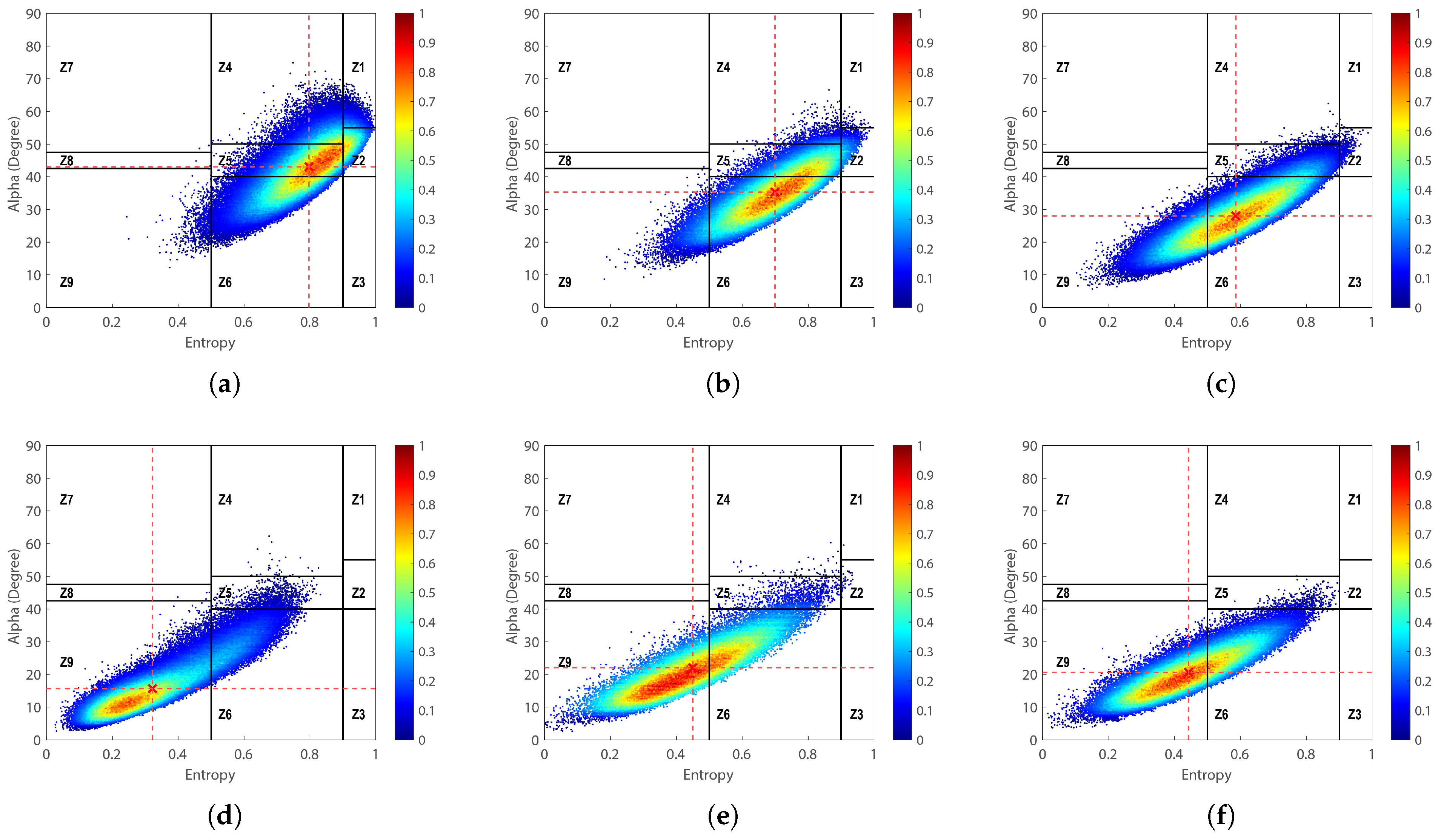

At present, many patch-based classification methods place excessive emphasis on spatial correlation, which often leads to insufficient utilization of polarimetric information. In the context of salt crust classification, however, numerous studies have demonstrated that polarimetric decomposition parameters are closely related to the physical properties of salt crust surfaces [

41]. In particular, the eigenvalues of the polarimetric coherency matrix exhibit strong correlations with surface roughness, and the associated scattering intensities provide clear physical interpretations [

42]. Cloude [

43] further analyzed the eigenvalues and eigenvectors derived from polarimetric coherency decomposition and reported a strong linear relationship between the anisotropy parameter A and the root mean square height of the surface. Building on these findings, Allain et al. [

44] proposed the Double-Bounce Eigenvalue Relative Difference (DERD) and the Single-Bounce Eigenvalue Relative Difference (SERD), among which SERD is particularly effective in high-entropy media for identifying dominant scattering mechanisms. Liu et al. [

45] subsequently explored the feasibility of using PolSAR data to distinguish salt crust types in the Lop Nur region by reinterpreting the physical meaning of the SERD parameter and inverting surface roughness from it, demonstrating its potential for salt crust identification. More recently, Li et al. [

46] investigated polarimetric decomposition parameters of different salt crust types in the Qarhan Salt Lake region and proposed a method based on statistical and texture similarity measures to characterize parameter differences among salt crust categories. Collectively, these studies indicate that polarimetric decomposition parameters possess discriminative capability for differentiating salt crust types, providing a physical basis for their identification.

For PolSAR image classification, different polarimetric features are often combined to form semantic representations that reflect land-cover category differences [

47]. However, the scattering differences among salt crust types are relatively limited, whereas polarimetric decomposition parameters are numerous and often redundant, especially for fully polarimetric SAR data with rich information content. Moreover, manually designing polarimetric features suitable for classification is typically labor-intensive and problem-dependent, which limits both efficiency and generalization capability. Consequently, a key challenge lies in how to further learn discriminative representations from existing polarimetric features to improve classification accuracy and robustness. As an unsupervised neural network, the convolutional autoencoder (CAE) provides an effective solution to this challenge by transforming original features into latent representations through nonlinear mappings [

48]. Owing to its simple structure, CAE not only facilitates efficient interpretation of SAR images but also enables the extraction of higher-level abstract features. In addition, CAEs have been shown to effectively suppress speckle noise inherent in SAR data. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of autoencoders in PolSAR-related tasks, where they were employed to automatically learn polarimetric features [

49] or optimize texture representations for improved classification performance [

50].

Thus, the main research objectives of this study are summarized as follows:

- 1.

To learn discriminative representations from polarimetric features to address the weak separability among salt crust types.

- 2.

To design a PolSAR classification method that improves salt crust classification performance by jointly modeling local and global information.

- 3.

To analyze the spatial and temporal variations of salt crust distributions using time-series PolSAR data.

To achieve these objectives, stable regions of different salt crust types are first selected as samples based on field surveys and unsupervised Wishart clustering results. A novel classification method integrating CAE, attention mechanisms, and ViT is then proposed. The framework consists of two stages: CAE pretraining and end-to-end classification. During the pretraining stage, the CAE encoder learns deeper local feature representations, while in the classification stage, attention mechanisms adaptively refine channel- and spatial-level features before they are fed into the ViT for global modeling. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method effectively distinguishes salt crust types in both fully polarimetric and dual-polarimetric data and provides accurate descriptions of their spatial distributions.

The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as follows:

- 1.

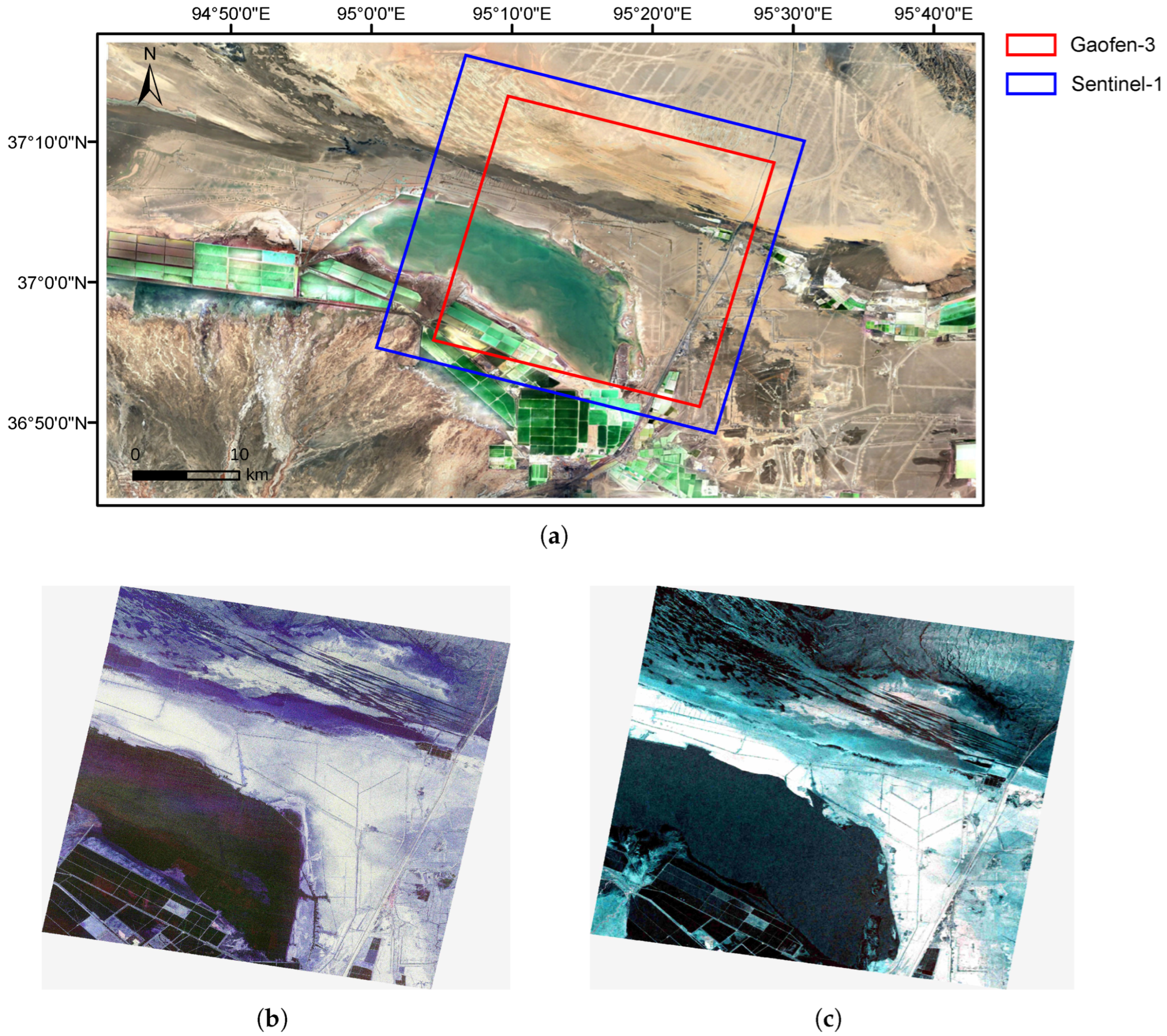

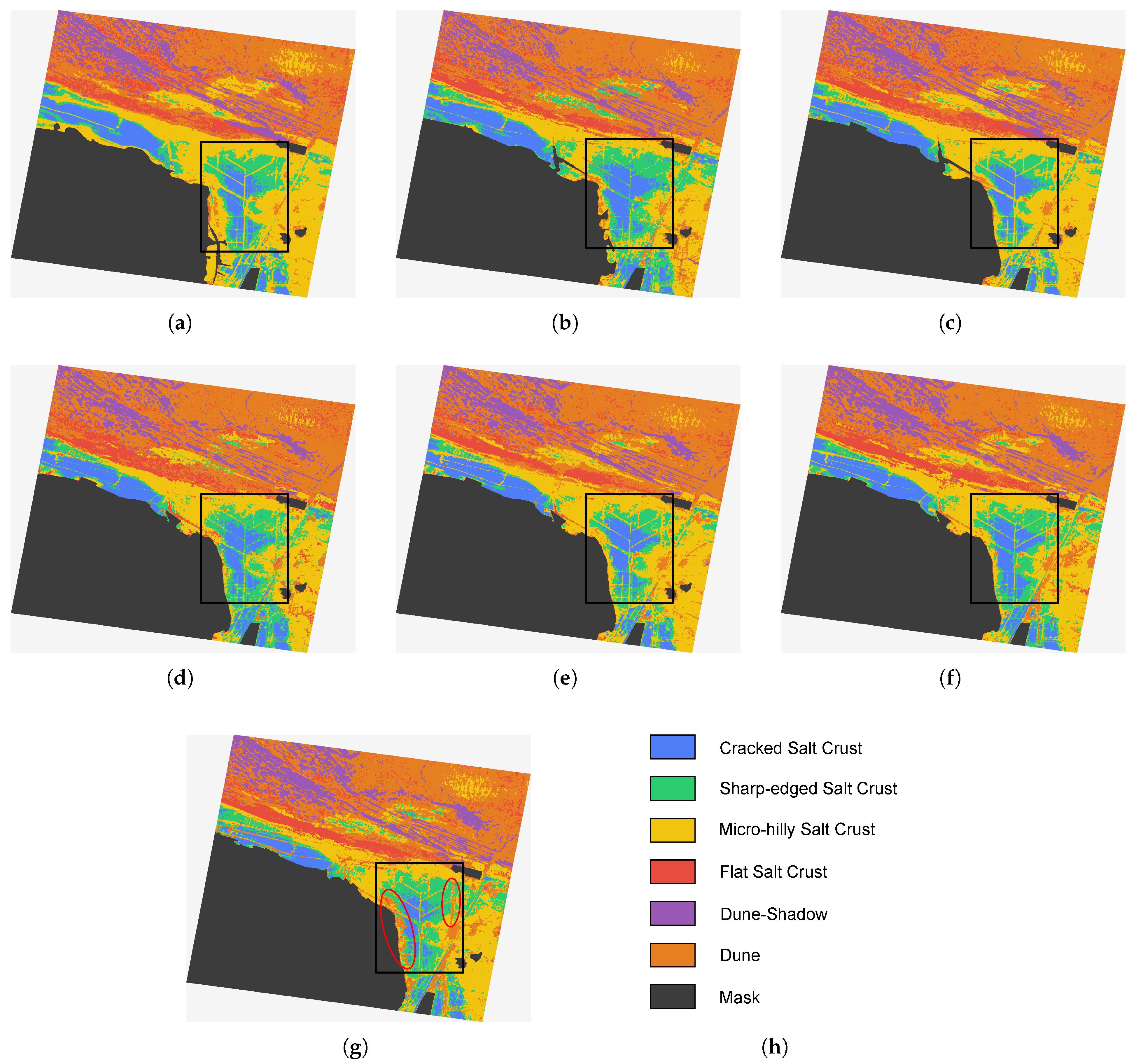

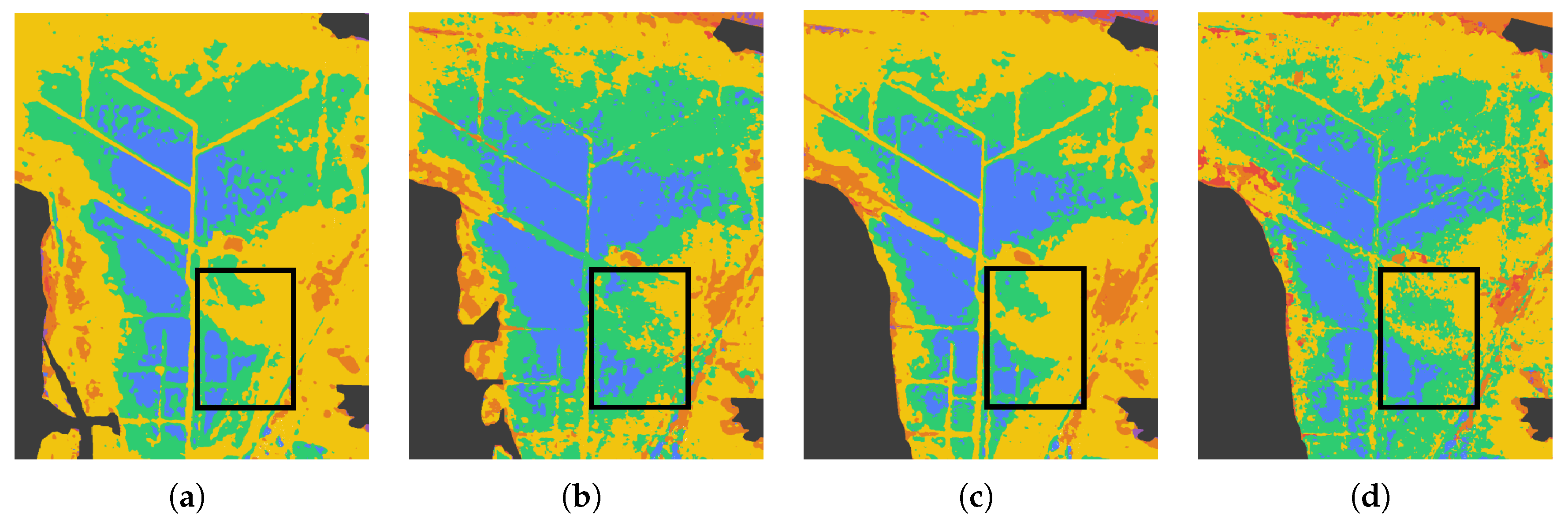

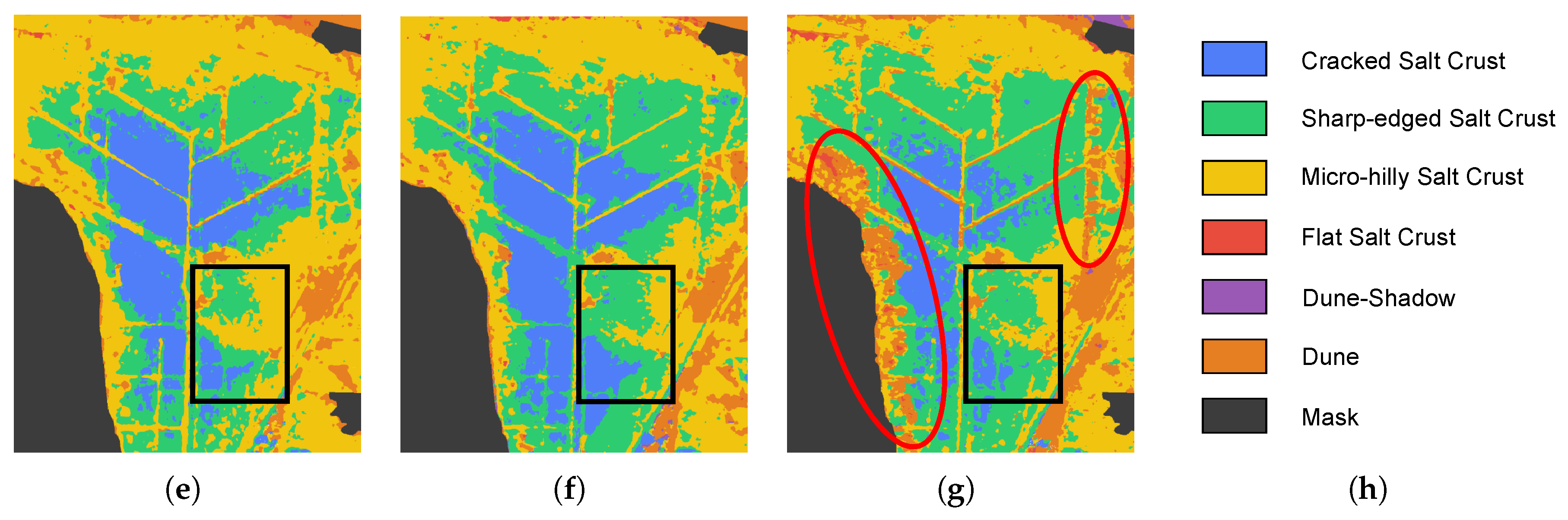

Based on multiple field surveys, salt crusts surrounding the Qarhan Salt Lake were classified into different types according to surface characteristics. Their scattering differences were analyzed using both fully polarimetric and dual-polarimetric data, enabling consistent characterization of spatial distributions.

- 2.

To address the weak scattering differences among salt crust types, a feature processing strategy based on a CAE was adopted. The CAE compresses redundant features in fully polarimetric data and learns latent representations from dual-polarimetric data to enhance class separability and robustness.

- 3.

Considering the spatial continuity and regularity of salt crust distribution, this paper proposes a PolSAR classification framework. The CAE extracts local features, the attention mechanism balances them across channels and spatial dimensions, and the ViT models global dependencies. By leveraging neighborhood information within image patches, the framework reduces misclassification and improves spatial coherence among salt crust types.

- 4.

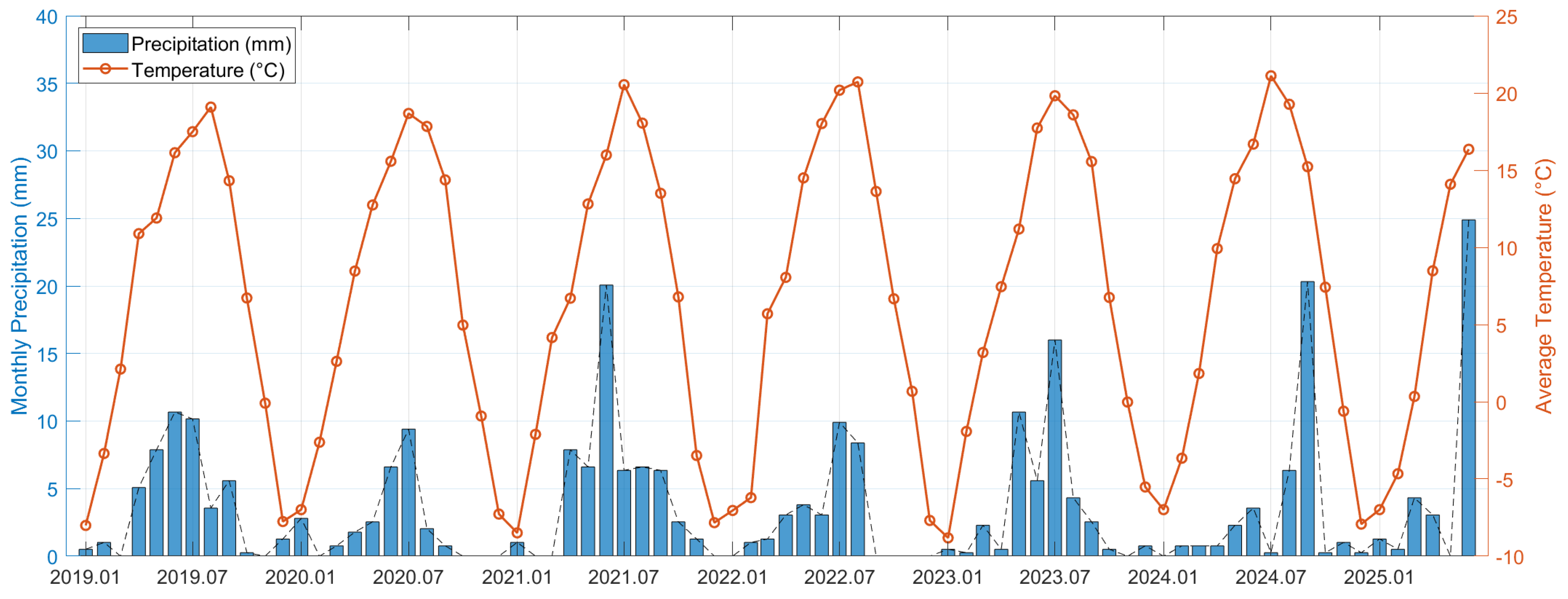

Time-series dual-polarimetric data from 2019 to 2025 were used to classify surface types at multiple time points. Based on these results, the temporal variations of salt crust distributions were analyzed, providing insights for salt lake resource development and environmental monitoring.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the study area and field investigations of salt crusts.

Section 3 presents the proposed method and its theoretical background in detail.

Section 4 analyzes the differences in scattering among different salt crust types and discusses the experimental results of salt crust classification.

Section 5 examines the results of the proposed method under different conditions and further discusses the temporal variations of salt crust types and future research directions. Finally,

Section 6 provides the summary and conclusions.