Vertical Monitoring of Chlorophyll-a and Phycocyanin Concentrations High-Latitude Inland Lakes Using Sentinel-3 OLCI

Highlights

- Remote sensing vertical inversion of vertical Chla and PC in lakes and reservoirs.

- Spatiotemporal distribution of Chla and PC at different water depths.

- Relationship between Chla and PC across different water depths.

- Driving factors of variation in the vertical distribution of Chla and PC.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

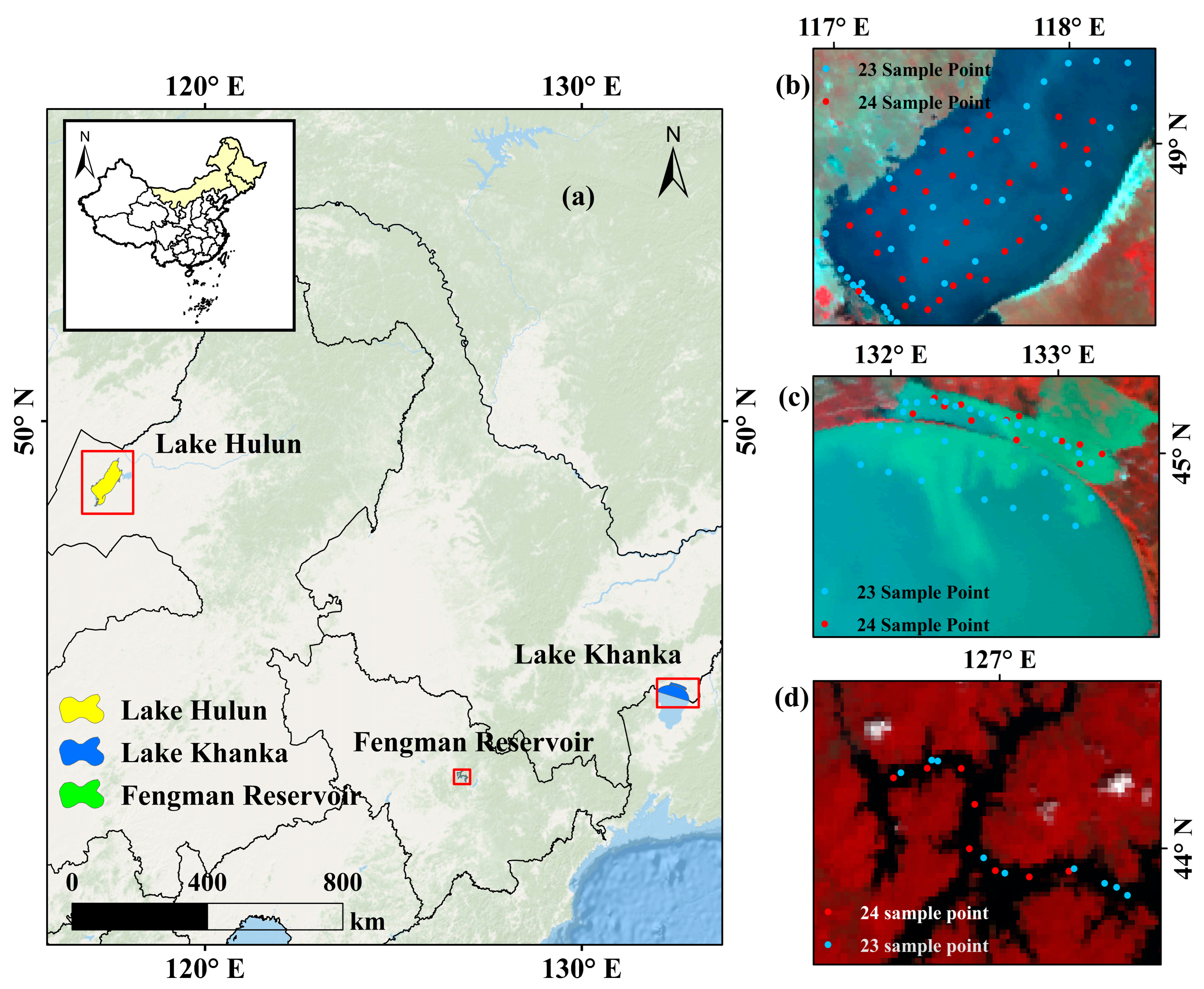

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Sampling and Laboratory Analysis

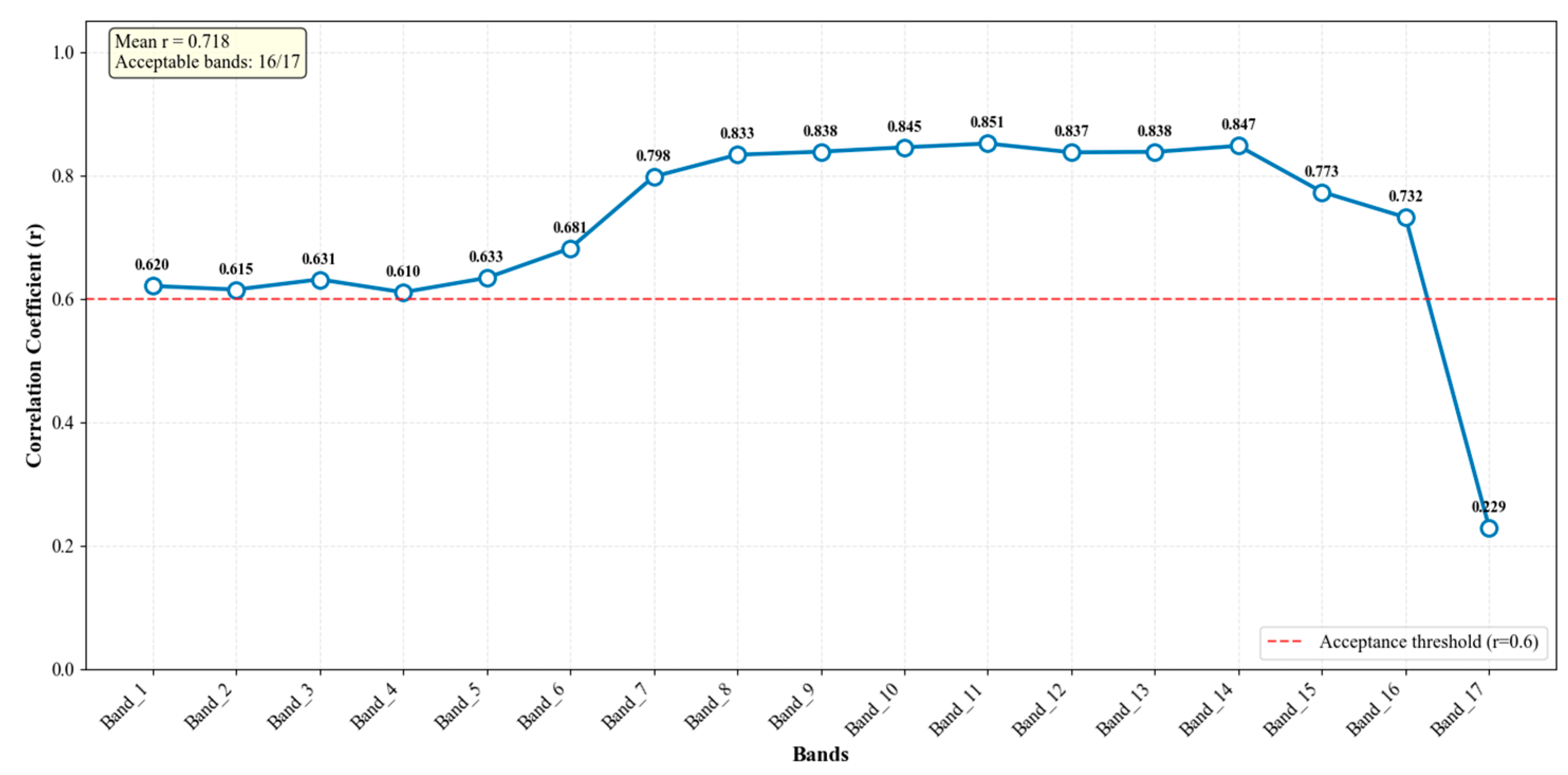

2.3. OLCI Data

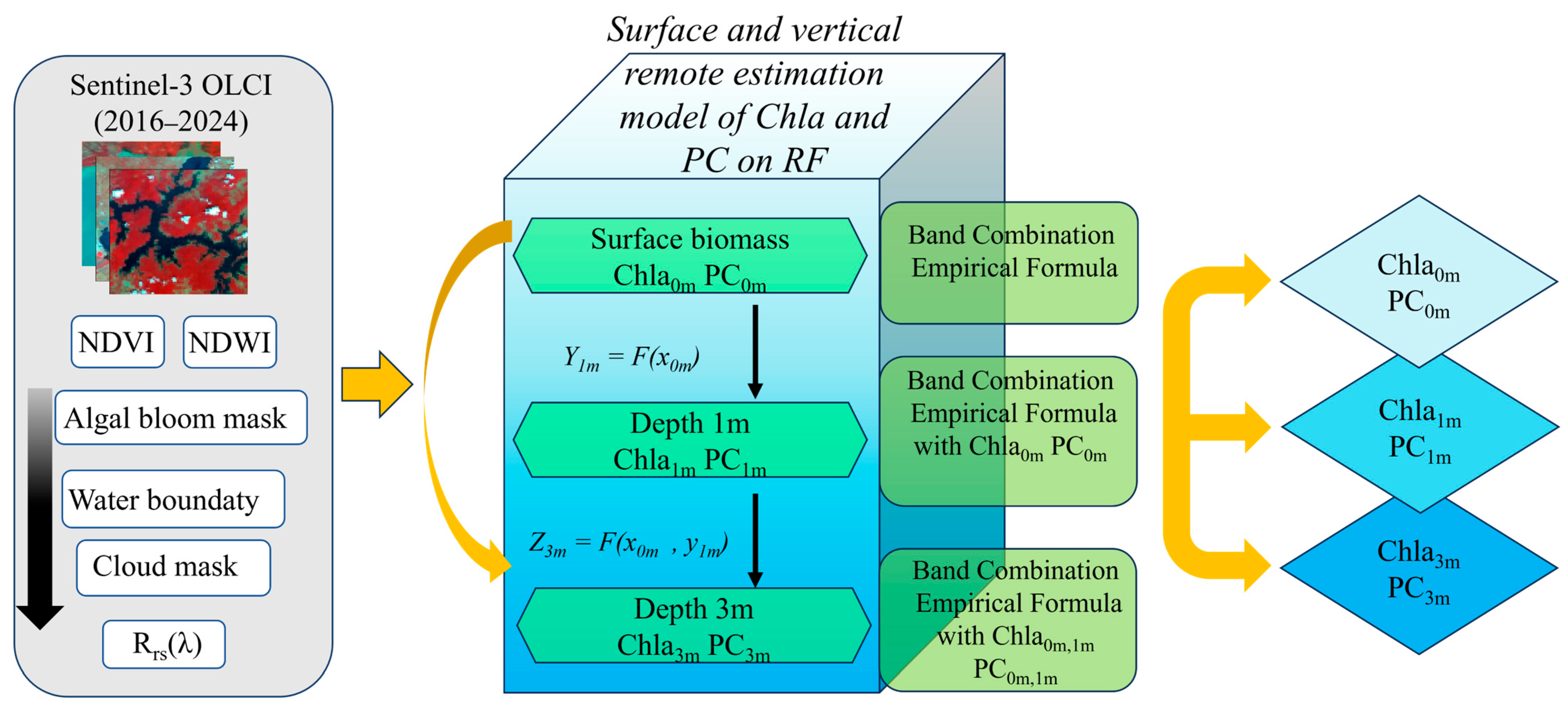

2.4. RF Model Establishment

2.5. Model Development

3. Results

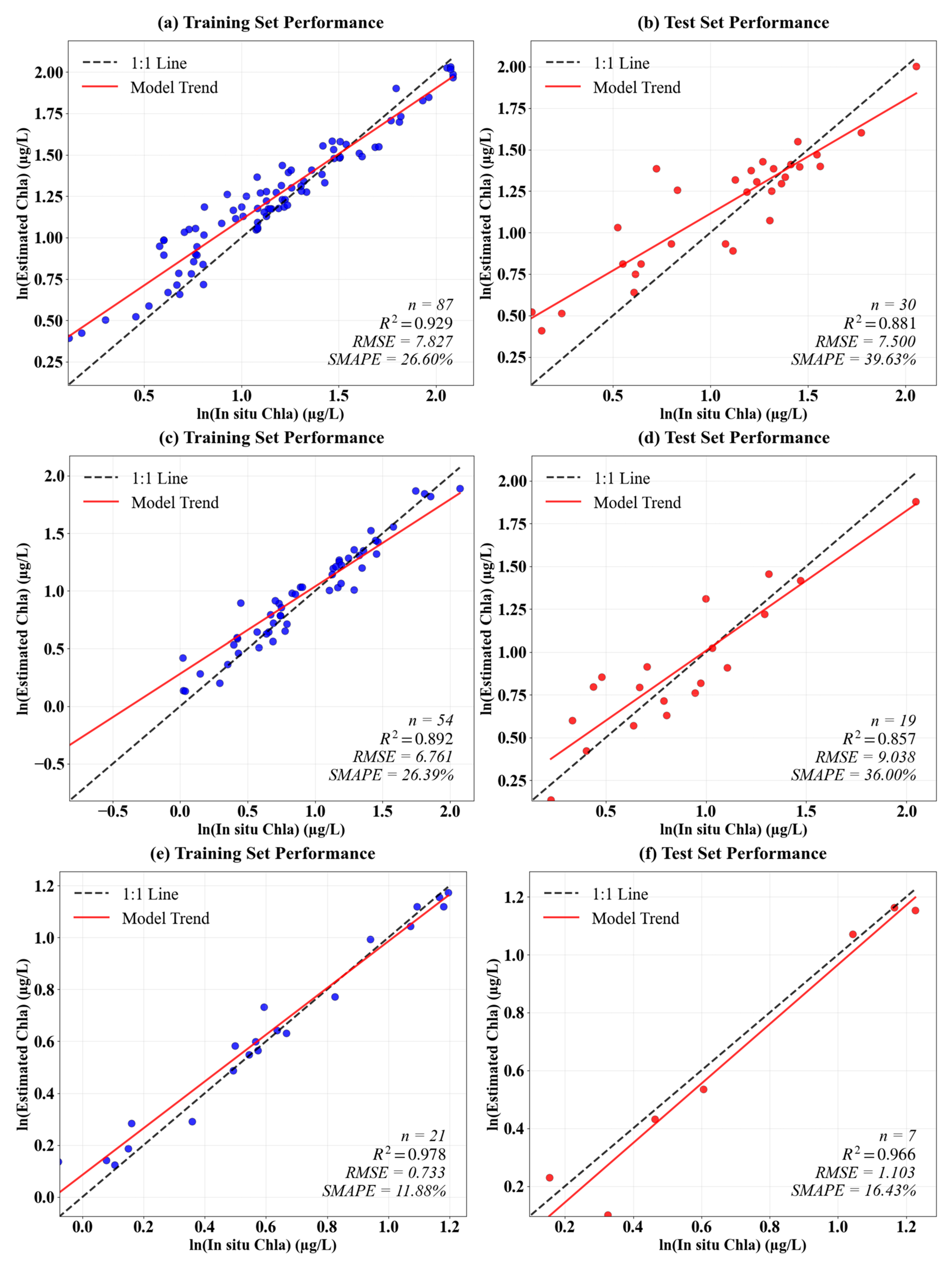

3.1. Model Accuracy

3.2. In Situ Measurement of Chla and PC

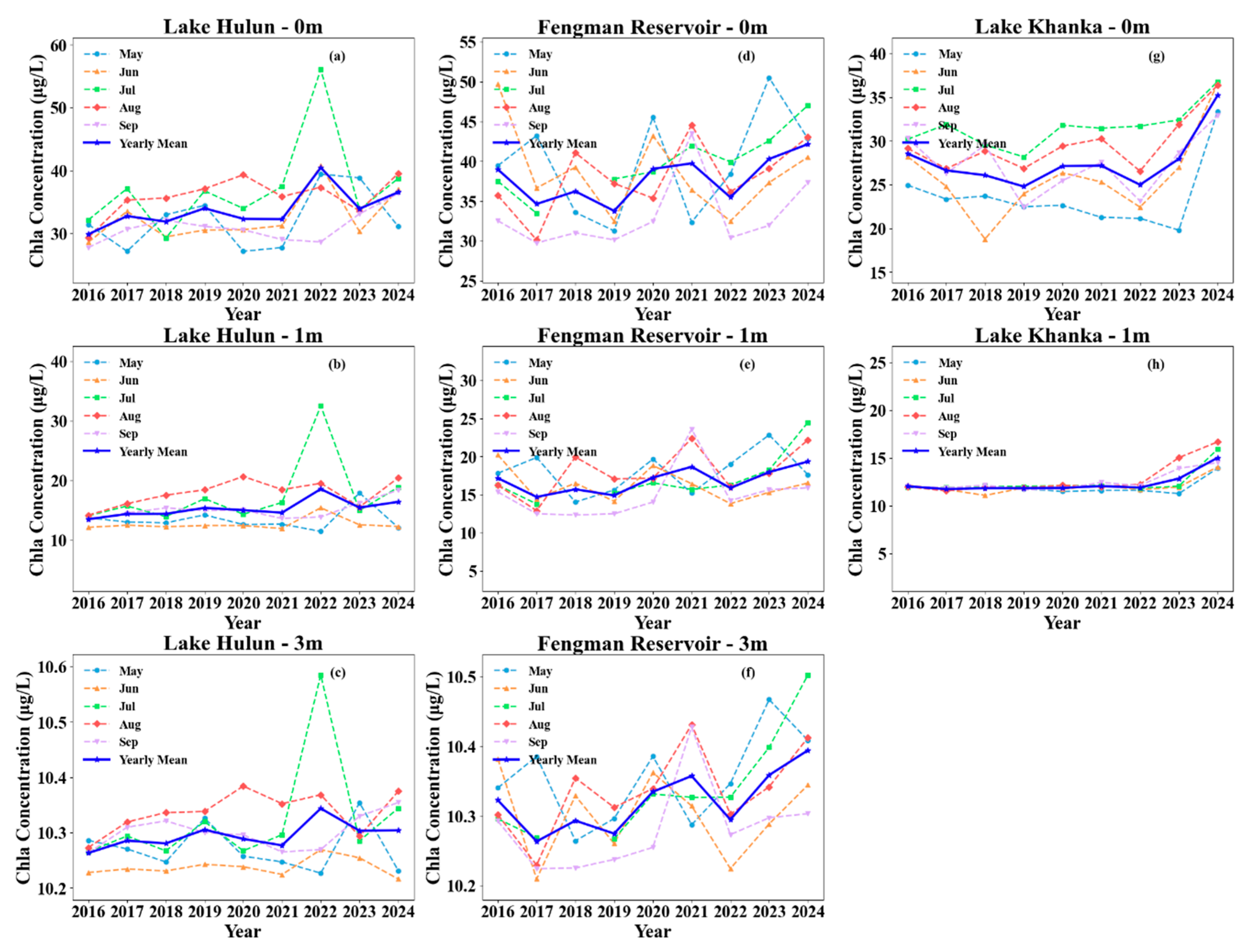

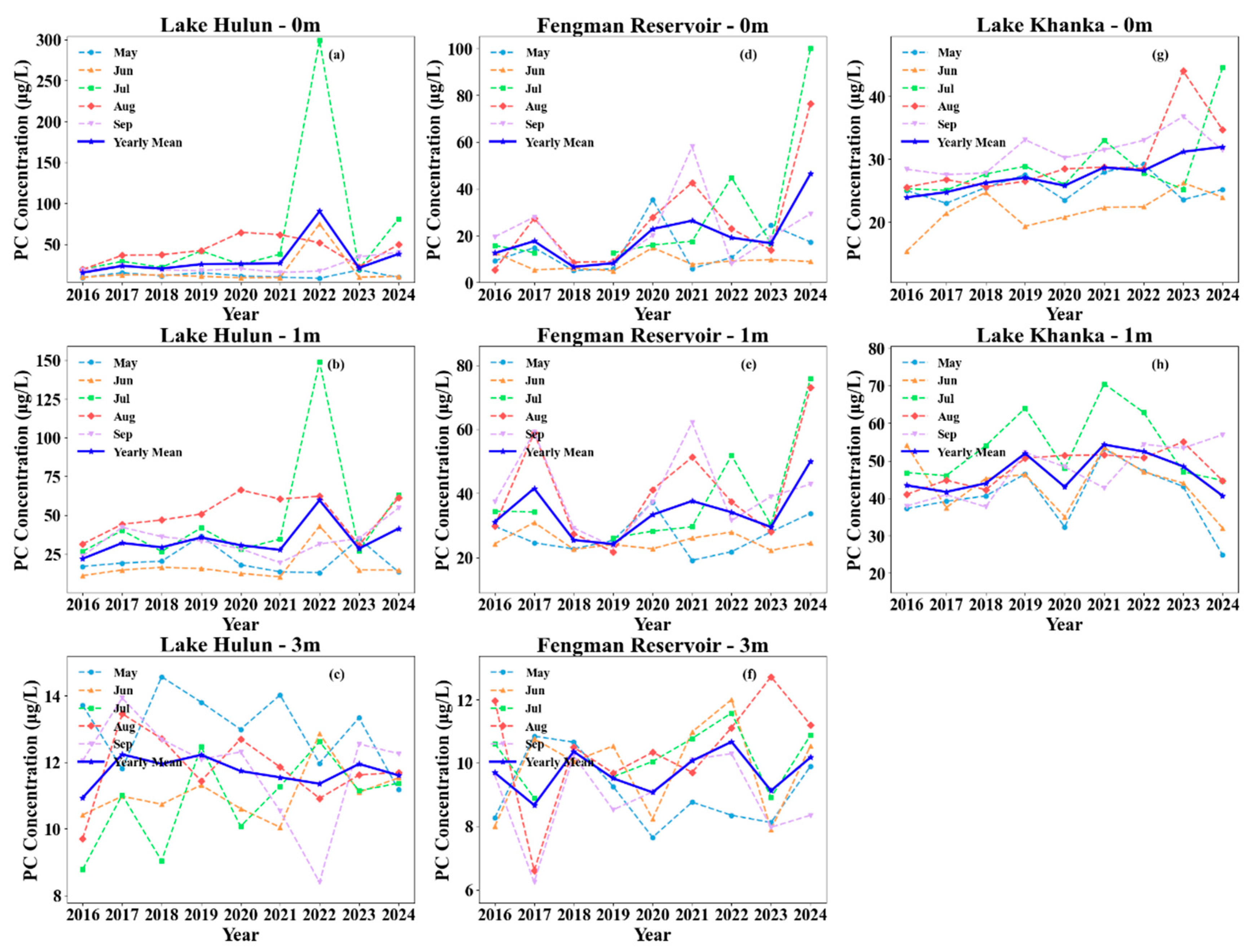

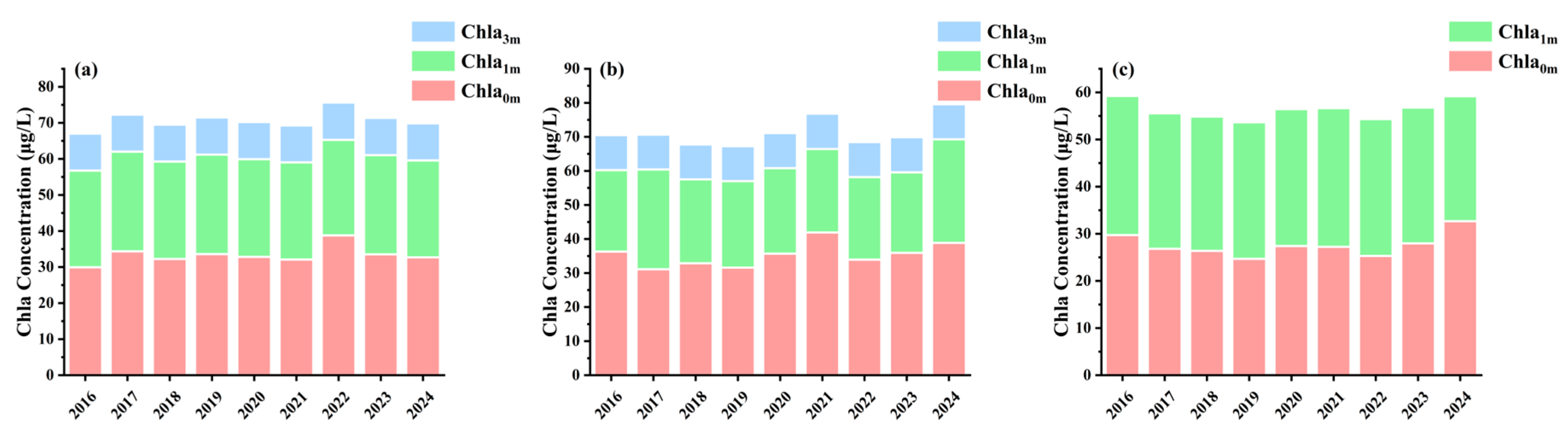

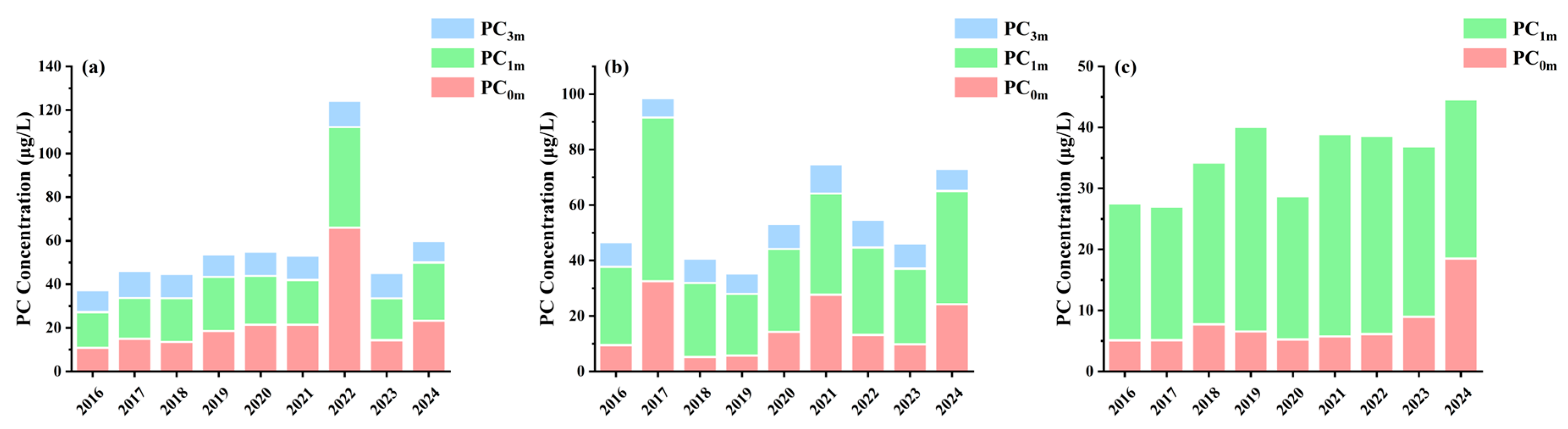

3.3. Spatiotemporal Variation in Chla and PC Concentration

3.4. Vertical Variations of Chla and PC Months

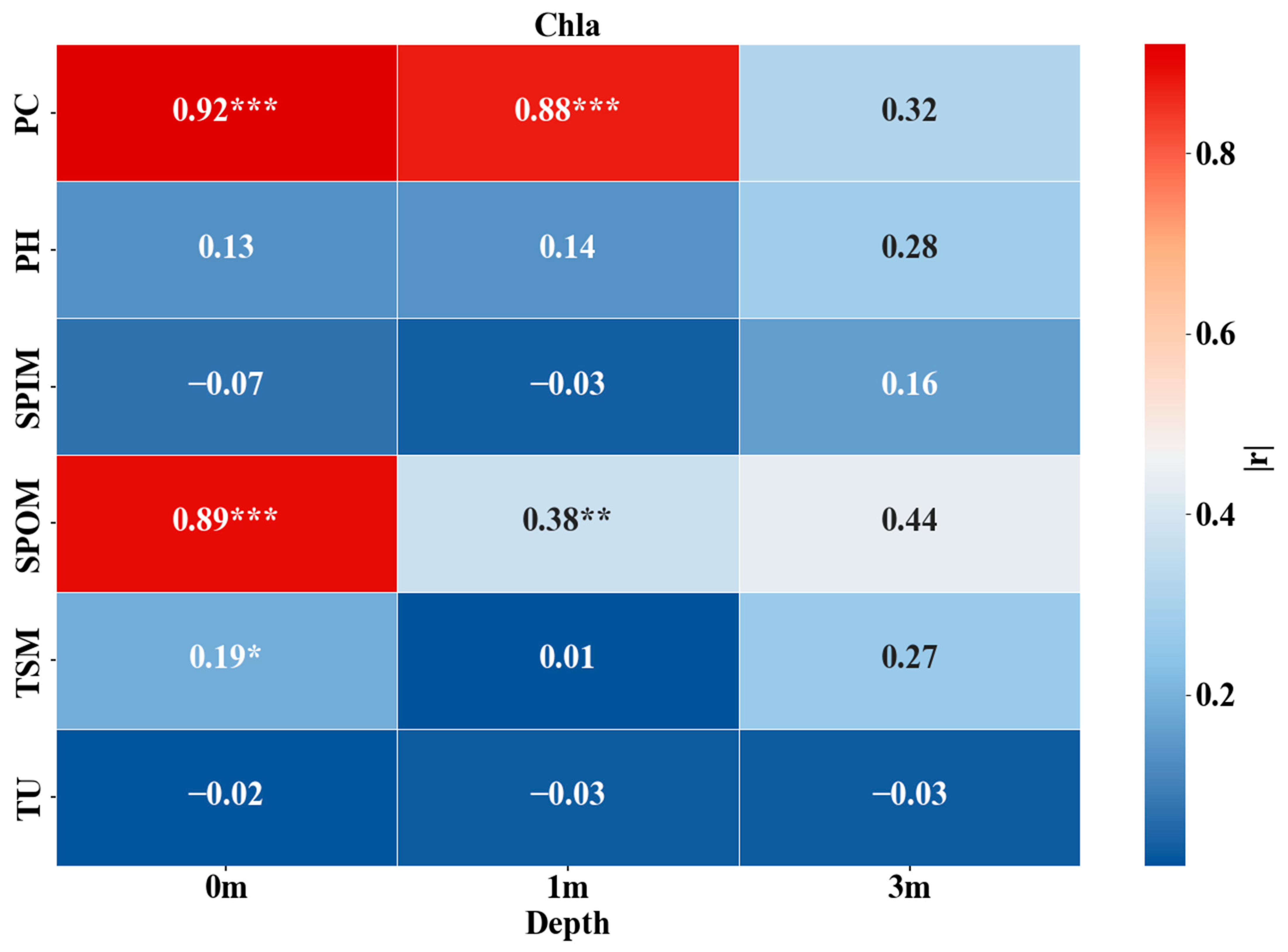

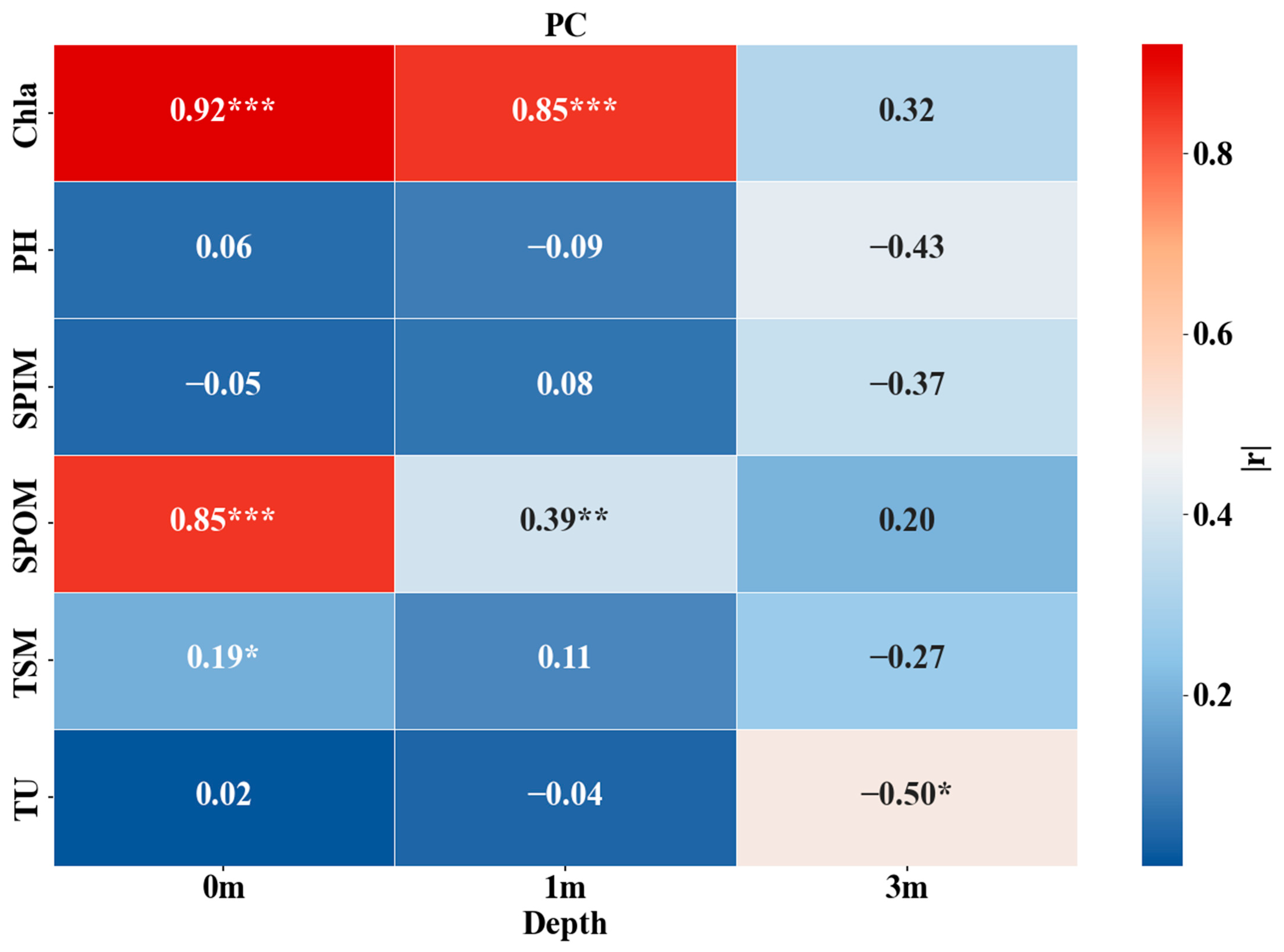

3.5. Vertical Influencing Factors of Chla and PC

4. Discussion

4.1. Vertical of Chla and PC

4.2. Monthly Trend in Vertical Chla and PC Distribution

4.3. Applicability and Uncertainty of the Model

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Chla | chlorophyll-a |

| PC | phycocyanin |

| Rrs | remote sensing reflectance |

| SPM | Suspended particulate matter |

| SPIM | Inorganic suspended particulate matter |

| SPOM | Organic suspended particulate matter |

| TU | Turbidity |

References

- Hou, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Gong, P. Mapping global lake aquatic vegetation dynamics using 10-m resolution satellite observations. Sci. Bull. 2024, 69, 3115–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, H.; Hou, X.; Feng, L.; Pi, X.; Kyzivat, E.D.; Zhang, Y.; Woodman, S.G.; Tang, L.; Cheng, X.; et al. Expansion of aquatic vegetation in northern lakes amplified methane emissions. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 18, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Ganesan, G. Advanced Evaluation Methodology for Water Quality Assessment Using Artificial Neural Network Approach. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 33, 3127–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Paerl, H.W.; Brookes, J.D.; Liu, J.; Jeppesen, E.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, H.; Shi, K.; Deng, J. Why Lake Taihu continues to be plagued with cyanobacterial blooms through 10 years (2007–2017) efforts. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 354–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenstein, E.M.; Kim, D.; Park, M.-H. Modeling for multi-temporal cyanobacterial bloom dominance and distributions using landsat imagery. Ecol. Inform. 2020, 59, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.C.; Ibelings, B.W.; Hoffmann, E.P.; Hamilton, D.P.; Brookes, J.D. Eco-physiological adaptations that favour freshwater cyanobacteria in a changing climate. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1394–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Song, K.; Paerl, H.W.; Jacinthe, P.-A.; Wen, Z.; Liu, G.; Tao, H.; Xu, X.; Kutser, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Global divergent trends of algal blooms detected by satellite during 1982–2018. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 2327–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Akbar, S.; Sun, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhang, L.; Lyu, K.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Z. Cyanobacterial dominance and succession: Factors, mechanisms, predictions, and managements. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 297, 113281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Deng, J.; Qin, B.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Jeppesen, E.; Tong, Y. Importance and vulnerability of lakes and reservoirs supporting drinking water in China. Fundam. Res. 2023, 3, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, L.; Song, K.; Wen, Z.; Liu, G.; Fang, C.; Shang, Y.; Li, S.; Tao, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Remote estimation of phycocyanin concentration in inland waters based on optical classification. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 899, 166363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fang, C.; Song, K.; Lyu, L.; Li, Y.; Lai, F.; Lyu, Y.; Wei, X. Monitoring phycocyanin concentrations in high-latitude inland lakes using Sentinel-3 OLCI data: The case of Lake Hulun, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Song, K.; Yan, Z.; Liu, G. Monitoring phycocyanin in global inland waters by remote sensing: Progress and future developments. Water Res. 2025, 275, 123176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdin, J.P. Monitoring water quality conditions in a large western reservoir with Landsat imagery. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 1985, 51, 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Vos, W.; Donze, M.; Buiteveld, H. On the reflectance spectrum of algae in water: The nature of the peak at 700 nm and its shift with varying concentration. Commun. Sanit. Eng. Water Manag. 1986, 86–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand, S. Landsat TM based quantification of chlorophyll-a during algae blooms in coastal waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1992, 13, 1913–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, R.P.; Tomlinson, M.C. Remote Sensing of Harmful Algal Blooms. In Remote Sensing of Coastal Aquatic Environments: Technologies, Techniques and Applications; Miller, R.L., Del Castillo, C.E., McKee, B.A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, R.; Zhan, S.; Liu, H.; Tong, S.; Yang, B.; Xu, M.; Ye, Z.; Huang, Y.; Shu, S.; Wu, Q.; et al. Comparison of satellite reflectance algorithms for estimating chlorophyll-a in a temperate reservoir using coincident hyperspectral aircraft imagery and dense coincident surface observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 178, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.; Cao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Ma, Y.; Xu, J. Spatial-temporal distributions of phytoplankton shifting, chlorophyll-a, and their influencing factors in shallow lakes using remote sensing. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hou, X.; Gao, W.; Li, F.; Guo, F.; Zhang, Y. Retrieving Lake Chla concentration from remote Sensing: Sampling time matters. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Meng, F.; Fu, P.; Jing, T.; Xu, J.; Yang, X. Tracking changes in chlorophyll-a concentration and turbidity in Nansi Lake using Sentinel-2 imagery: A novel machine learning approach. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Vilas, L.; Spyrakos, E.; Torres Palenzuela, J.M. Neural network estimation of chlorophyll a from MERIS full resolution data for the coastal waters of Galician rias (NW Spain). Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.J.; Kavianpour, M.R. Development of wavelet-ANN models to predict water quality parameters in Hilo Bay, Pacific Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 98, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinshaw Tadesse, A.; Surbeck Cristiane, Q.; Yasarer, H.; Najjar, Y. Artificial Neural Network for Prediction of Total Nitrogen and Phosphorus in US Lakes. J. Environ. Eng. 2019, 145, 04019032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yang, G.; Wan, R.; Hörmann, G.; Huang, J.; Fohrer, N.; Zhang, L. Combining multivariate statistical techniques and random forests model to assess and diagnose the trophic status of Poyang Lake in China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 83, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, H.; Derot, J. Application of the Random Forest model for chlorophyll-a forecasts in fresh and brackish water bodies in Japan, using multivariate long-term databases. J. Hydroinformatics 2017, 20, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, R.; Yeh, H.-D.; Abbasi, M.; Kachoosangi, F.T.; Moazami, S. Uncertainty analysis of support vector machine for online prediction of five-day biochemical oxygen demand. J. Hydrol. 2015, 527, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Cho, K.H.; Park, J.; Cha, S.M.; Kim, J.H. Development of early-warning protocol for predicting chlorophyll-a concentration using machine learning models in freshwater and estuarine reservoirs, Korea. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 502, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, H.; Ma, R.; Loiselle, S.; Zhang, M. A Remote Sensing Approach to Estimate Vertical Profile Classes of Phytoplankton in a Eutrophic Lake. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 14403–14427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Xu, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhang, C.; Xin, Z.; Liu, Z. SVR model and OLCI images reveal a declining trend in phycocyanin levels in typical lakes across Northeast China. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 85, 102965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Ma, C.F.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Ye, X.M.; Yu, Z.F.; Tian, L.Q. Machine learning-based retrieval of chlorophyll-a and total suspended matter from HY-3A CZI: Model development, validation, and application. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 227, 613–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simis, S.G.H.; Peters, S.W.M.; Gons, H.J. Remote sensing of the cyanobacterial pigment phycocyanin in turbid inland water. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2005, 50, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, M.W. A current review of empirical procedures of remote sensing in inland and near-coastal transitional waters. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 6855–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Simis, S.G.H.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Song, K.; Lyu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Shi, K. A Four-Band Semi-Analytical Model for Estimating Phycocyanin in Inland Waters From Simulated MERIS and OLCI Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2018, 56, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, S.L.; Cortés, A.; Forrest, A.L.; Legleiter, C.J.; Guild, L.S.; Jin, Y.; Schladow, S.G. Monitoring cyanobacteria temporal dynamics in a hypereutrophic lake using remote sensing: From multispectral to hyperspectral. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 39, 101704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Feng, L.; Dai, Y.; Hu, C.; Gibson, L.; Tang, J.; Lee, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cai, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Global mapping reveals increase in lacustrine algal blooms over the past decade. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhao, D.; Hu, C.; Xu, W.; Anderson, D.M.; Li, Y.; Song, X.-P.; Boyce, D.G.; Gibson, L.; et al. Coastal phytoplankton blooms expand and intensify in the 21st century. Nature 2023, 615, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, G.; Ma, J.; Shi, Y.; Chen, X. Hyperspectral remote sensing of cyanobacterial pigments as indicators of the iron nutritional status of cyanobacteria-dominant algal blooms in eutrophic lakes. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.S.; Pyo, J.; Kwon, Y.-H.; Duan, H.; Cho, K.H.; Park, Y. Drone-based hyperspectral remote sensing of cyanobacteria using vertical cumulative pigment concentration in a deep reservoir. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Ma, R.; Hu, C. Evaluation of remote sensing algorithms for cyanobacterial pigment retrievals during spring bloom formation in several lakes of East China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 126, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, J.; Codd, G.A.; Paerl, H.W.; Ibelings, B.W.; Verspagen, J.M.H.; Visser, P.M. Cyanobacterial blooms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, K.; Wilson, J.; Tedesco, L.; Li, L.; Pascual, D.L.; Soyeux, E. Hyperspectral remote sensing of cyanobacteria in turbid productive water using optically active pigments, chlorophyll a and phycocyanin. Remote Sens. Environ. 2008, 112, 4009–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.H.; Sultan, M.I.; Boyer, G.L.; Twiss, M.R.; Konopko, E. Mapping cyanobacterial blooms in the Great Lakes using MODIS. J. Great Lakes Res. 2009, 35, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Mishra, D.R.; Lee, Z.; Tucker, C.S. Quantifying cyanobacterial phycocyanin concentration in turbid productive waters: A quasi-analytical approach. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 133, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Tedesco, L.; Hall, B.; Li, Z. Hyperspectral retrieval of phycocyanin in potable water sources using genetic algorithm–partial least squares (GA–PLS) modeling. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2012, 18, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Yan, S. Dynamic monitoring of phycocyanin concentration in Chaohu Lake of China using Sentinel-3 images and its indication of cyanobacterial blooms. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G.; Song, K.; Tao, H.; Zhao, F.; Li, S.; Shi, S.; Shang, Y. Retrieval of Chla Concentrations in Lake Xingkai Using OLCI Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, H. The status and development of the non-traditional lake water color remote sensing. J. Lake Sci. 2016, 28, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, R.; Xue, K.; Cao, Z.; Chu, Q.; Jing, Y. Optimized remote sensing estimation of the lake algal biomass by considering the vertically heterogeneous chlorophyll distribution: Study case in Lake Chaohu of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grósz, J.; Waltner, I.; Vekerdy, Z. First analysis results of in situ measurements for algae monitoring in lake Naplás (Hungary). Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 14, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammartino, M.; Marullo, S.; Santoleri, R.; Scardi, M. Modelling the Vertical Distribution of Phytoplankton Biomass in the Mediterranean Sea from Satellite Data: A Neural Network Approach. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ma, Y.; Huang, J.; Yang, J.; Su, D.; Wang, X.H. Deriving vertical profiles of chlorophyll-a concentration in the upper layer of seawaters using ICESat-2 photon-counting lidar. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 33320–33336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Synergistic detection of chlorophyll-a concentration vertical profile by spaceborne lidar ICESat-2 and passive optical observations. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 132, 104035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Y.; Gu, Q.; Han, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, P.; Lin, L.; Lv, W.; Wu, L.; Wu, L.; et al. Lidar-Observed Diel Vertical Variations of Inland Chlorophyll a Concentration. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, J.-M. Ocean color remote-sensing and the subsurface vertical structure of phytoplankton pigments. Deep. Sea Res. Part A. Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1992, 39, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silulwane, N.F.; Richardson, A.J.; Shillington, F.A.; Mitchell-Innes, B.A. Identification and classification of vertical chlorophyll patterns in the Benguela upwelling system and Angola-Benguela front using an artificial neural network. Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 2006, 23, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H.; Wei, X.Q.; Huang, Z.H.; Liu, H.Z.; Ma, R.H.; Wang, M.H.; Hu, M.Q.; Jiang, L.D.; Xue, K. Monitoring the Vertical Variations in Chlorophyll-a Concentration in Lake Chaohu Using the Geostationary Ocean Color Imager. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Ma, R.; Shen, M.; Wu, J.; Hu, M.; Guo, Y.; Cao, Z.; Xiong, J. Horizontal and vertical migration of cyanobacterial blooms in two eutrophic lakes observed from the GOCI satellite. Water Res. 2023, 240, 120099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Bi, S.; Xu, J.; Guo, F.; Lyu, H.; Dong, X.; Cai, X. Utilization of GOCI data to evaluate the diurnal vertical migration of Microcystis aeruginosa and the underlying driving factors. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 310, 114734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.R.; Meyer, D.L.; Waite, A.M.; Ivey, G.N.; Hamilton, D.P. Disaggregation of Microcystis aeruginosa colonies under turbulent mixing: Laboratory experiments in a grid-stirred tank. Hydrobiologia 2004, 519, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, D.; Du, H.; Pang, Y.; Hu, K.; Wang, J. Separation of wind’s influence on harmful cyanobacterial blooms. Water Res. 2016, 98, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Shang, Y.; Song, K.; Liu, G.; Hou, J.; Lyu, L.; Tao, H.; Li, S.; He, C.; Shi, Q.; et al. Composition of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in lakes responds to the trophic state and phytoplankton community succession. Water Res. 2022, 224, 119073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Li, L.; Tedesco, L.P.; Li, S.; Clercin, N.A.; Hall, B.E.; Li, Z.; Shi, K. Hyperspectral determination of eutrophication for a water supply source via genetic algorithm–partial least squares (GA–PLS) modeling. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 426, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Lu, D.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Du, J. Remote sensing of chlorophyll-a concentration for drinking water source using genetic algorithms (GA)-partial least square (PLS) modeling. Ecol. Inform. 2012, 10, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhellemont, Q.; Ruddick, K. Atmospheric correction of Sentinel-3/OLCI data for mapping of suspended particulate matter and chlorophyll-a concentration in Belgian turbid coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C. A novel ocean color index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Song, C.; Fang, C.; Xu, Y.; Xin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, C. Spatiotemporal variation of long-term surface and vertical suspended particulate matter in the Liaohe estuary, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 151, 110288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Du, C.; Liu, G.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lyu, H.; Mu, M.; Miao, S.; et al. An approach for retrieval of horizontal and vertical distribution of total suspended matter concentration from GOCI data over Lake Hongze. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, L.; Song, K.; Li, Y.; Lyu, H.; Wen, Z.; Fang, C.; Bi, S.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; et al. An OLCI-based algorithm for semi-empirically partitioning absorption coefficient and estimating chlorophyll a concentration in various turbid case-2 waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 239, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Hu, C.; Duan, H.; Cannizzaro, J.; Ma, R. A novel MERIS algorithm to derive cyanobacterial phycocyanin pigment concentrations in a eutrophic lake: Theoretical basis and practical considerations. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 154, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Fang, C.; Song, K.; Wang, X.; Wen, Z.; Shang, Y.; Tao, H.; Lyu, Y. Spatiotemporal variation in biomass abundance of different algal species in Lake Hulun using machine learning and Sentinel-3 images. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Qin, B.; Brookes, J.D.; Shi, K.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, M.; Yan, W.; Wang, Z. The influence of changes in wind patterns on the areal extension of surface cyanobacterial blooms in a large shallow lake in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 518–519, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Lv, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Li, N. Common fate of sister lakes in Hulunbuir Grassland: Long-term harmful algal bloom crisis from multi-source remote sensing insights. J. Hydrol. 2021, 594, 125970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Luo, J.; Cao, Z.; Xue, K.; Qi, T.; Ma, J.; Liu, D.; Song, K.; Feng, L.; Duan, H. Random forest: An optimal chlorophyll-a algorithm for optically complex inland water suffering atmospheric correction uncertainties. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R. Intention Recognition Method for Spatial Non-cooperative Target Based on Improved Random Forest. Adv. Space Res. 2025, 77, 714–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhi, M.; Zhang, Y. Combined Generalized Additive model and Random Forest to evaluate the influence of environmental factors on phytoplankton biomass in a large eutrophic lake. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, H.; Wang, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. Variations in optical scattering and backscattering by organic and inorganic particulates in Chinese lakes of Taihu, Chaohu and Dianchi. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2015, 25, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Depth | Lake | Sample Size | Mean | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 m | Hulun Lake | 72 | 43.15 | 3.35 | 380.58 |

| 0 m | Songhua Lake | 18 | 3.37 | 1.21 | 6.37 |

| 0 m | Khanka Lake | 46 | 40.25 | 3.98 | 254.81 |

| 1 m | Hulun Lake | 22 | 11.45 | 0.14 | 29.55 |

| 1 m | Songhua Lake | 12 | 2.54 | 1.05 | 4.84 |

| 1 m | Khanka Lake | 38 | 31.60 | 2.74 | 166.00 |

| 3 m | Hulun Lake | 16 | 8.94 | 2.91 | 16.85 |

| 3 m | Songhua Lake | 11 | 2.32 | 0.83 | 4.63 |

| Depth | Lake | Sample Size | Mean | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 m | Hulun Lake | 72 | 138.63 | 0.12 | 2548.47 |

| 0 m | Songhua Lake | 18 | 11.93 | 0.05 | 62.14 |

| 0 m | Khanka Lake | 46 | 246.49 | 0.62 | 1862.44 |

| 1 m | Hulun Lake | 22 | 8.65 | 0.31 | 86.24 |

| 1 m | Songhua Lake | 12 | 9.36 | 0.02 | 55.30 |

| 1 m | Khanka Lake | 38 | 202.95 | 0.73 | 2112.49 |

| 3 m | Hulun Lake | 16 | 11.72 | 0.17 | 94.19 |

| 3 m | Songhua Lake | 11 | 6.03 | 0.03 | 26.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shen, J.; Wen, Z.; Song, K.; Tao, H.; Liu, S.; Yan, Z.; Fang, C.; Lyu, L. Vertical Monitoring of Chlorophyll-a and Phycocyanin Concentrations High-Latitude Inland Lakes Using Sentinel-3 OLCI. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010139

Shen J, Wen Z, Song K, Tao H, Liu S, Yan Z, Fang C, Lyu L. Vertical Monitoring of Chlorophyll-a and Phycocyanin Concentrations High-Latitude Inland Lakes Using Sentinel-3 OLCI. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010139

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Jinpeng, Zhidan Wen, Kaishan Song, Hui Tao, Shizhuo Liu, Zhaojiang Yan, Chong Fang, and Lili Lyu. 2026. "Vertical Monitoring of Chlorophyll-a and Phycocyanin Concentrations High-Latitude Inland Lakes Using Sentinel-3 OLCI" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010139

APA StyleShen, J., Wen, Z., Song, K., Tao, H., Liu, S., Yan, Z., Fang, C., & Lyu, L. (2026). Vertical Monitoring of Chlorophyll-a and Phycocyanin Concentrations High-Latitude Inland Lakes Using Sentinel-3 OLCI. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010139