Global–Local Mamba-Based Dual-Modality Fusion for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification

Highlights

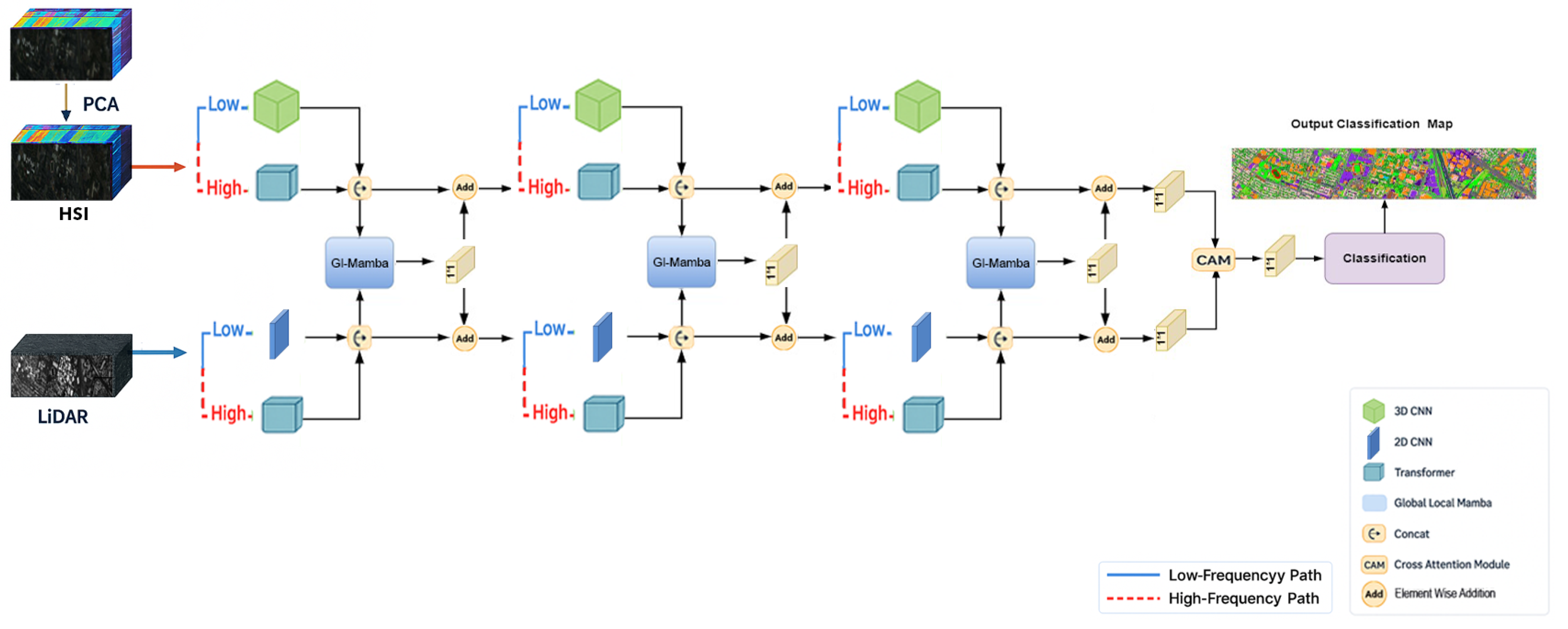

- We propose GL-Mamba, a frequency-aware dual-modality fusion network that combines low-/high-frequency decomposition, global–local Mamba blocks, and cross-attention to jointly exploit hyperspectral and LiDAR information for land-cover classification.

- GL-Mamba achieves state-of-the-art performance on the Trento, Augsburg, and Houston2013 benchmarks, with overall accuracies of 99.71%, 94.58%, and 99.60%, respectively, while producing smoother and more coherent classification maps than recent CNN-, transformer-, and Mamba-based baselines.

- The results demonstrate that linear-complexity Mamba state-space models are a competitive and efficient alternative to heavy transformer architectures for large-scale multimodal remote sensing, enabling accurate HSI–LiDAR fusion under practical computational constraints.

- The proposed frequency-aware and cross-modal design can be extended to other sensor combinations and tasks (e.g., multispectral–LiDAR mapping, change detection), providing a general blueprint for building scalable and robust multimodal networks in remote sensing applications.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The Global–Local Mamba dual-modality fusion network is developed which uses a state-space Mamba block to learn both local spectral–spatial context as well as long-range dependencies from hyperspectral and LiDAR inputs with linear complexity.

- A dual-branch frequency decomposition is introduced to decompose hyperspectral and LiDAR signals into low- and high-frequency components, with each component processed separately using lightweight 3D/2D CNNs and compact transformers, preserving fine detail and coarser structure while minimising computational costs.

- Our approach has been rigorously tested on the Trento, Augsburg, and Houston2013 benchmarks with different patch sizes, proving its robustness and generalizability. When compared against eight state-of-the-art baselines, it always comes out on top in terms of kappa, average accuracy, and overall accuracy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preliminaries

2.2. Overall Architecture

2.3. Frequency-Aware Decomposition

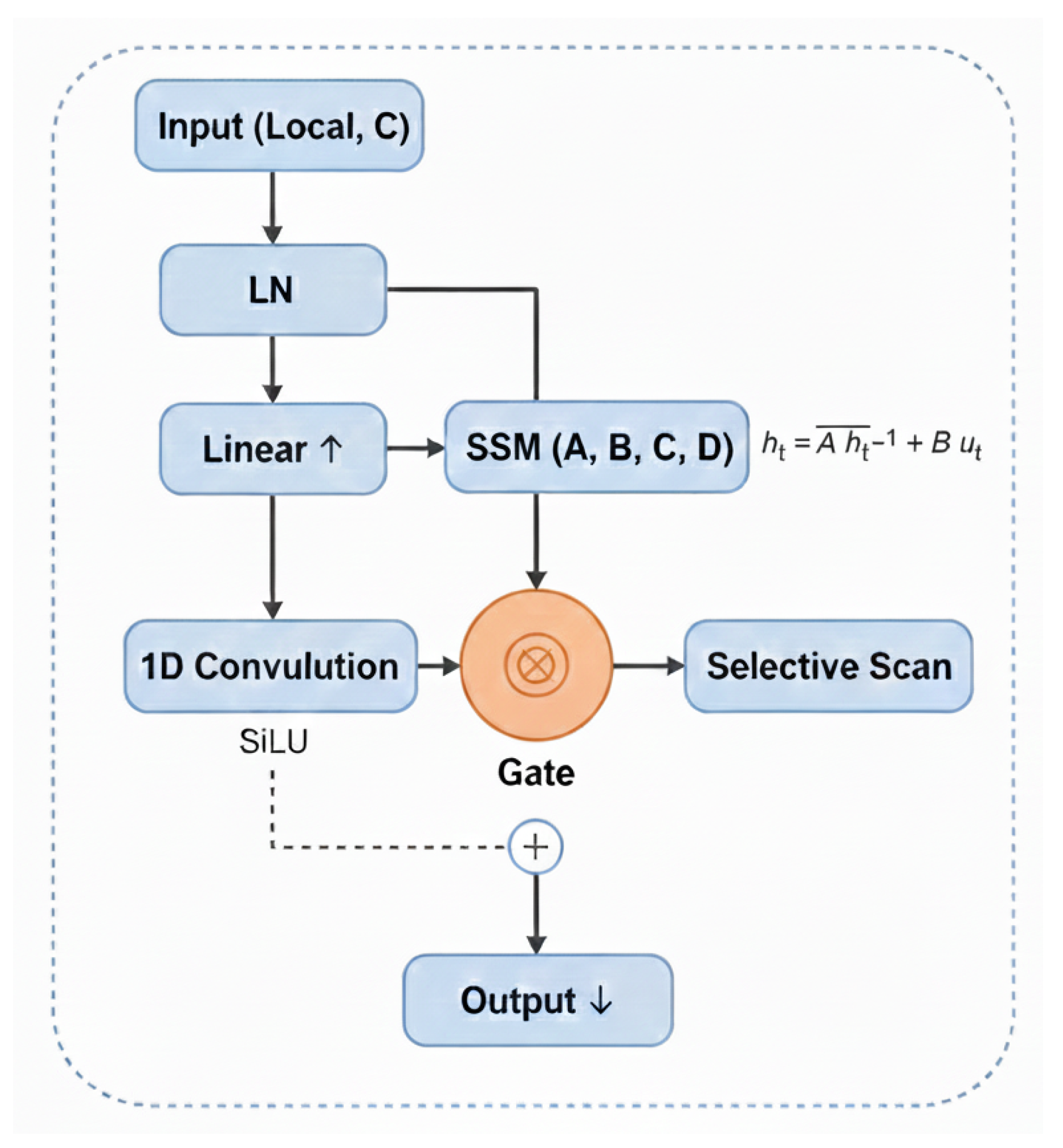

2.4. Global–Local Mamba Fusion

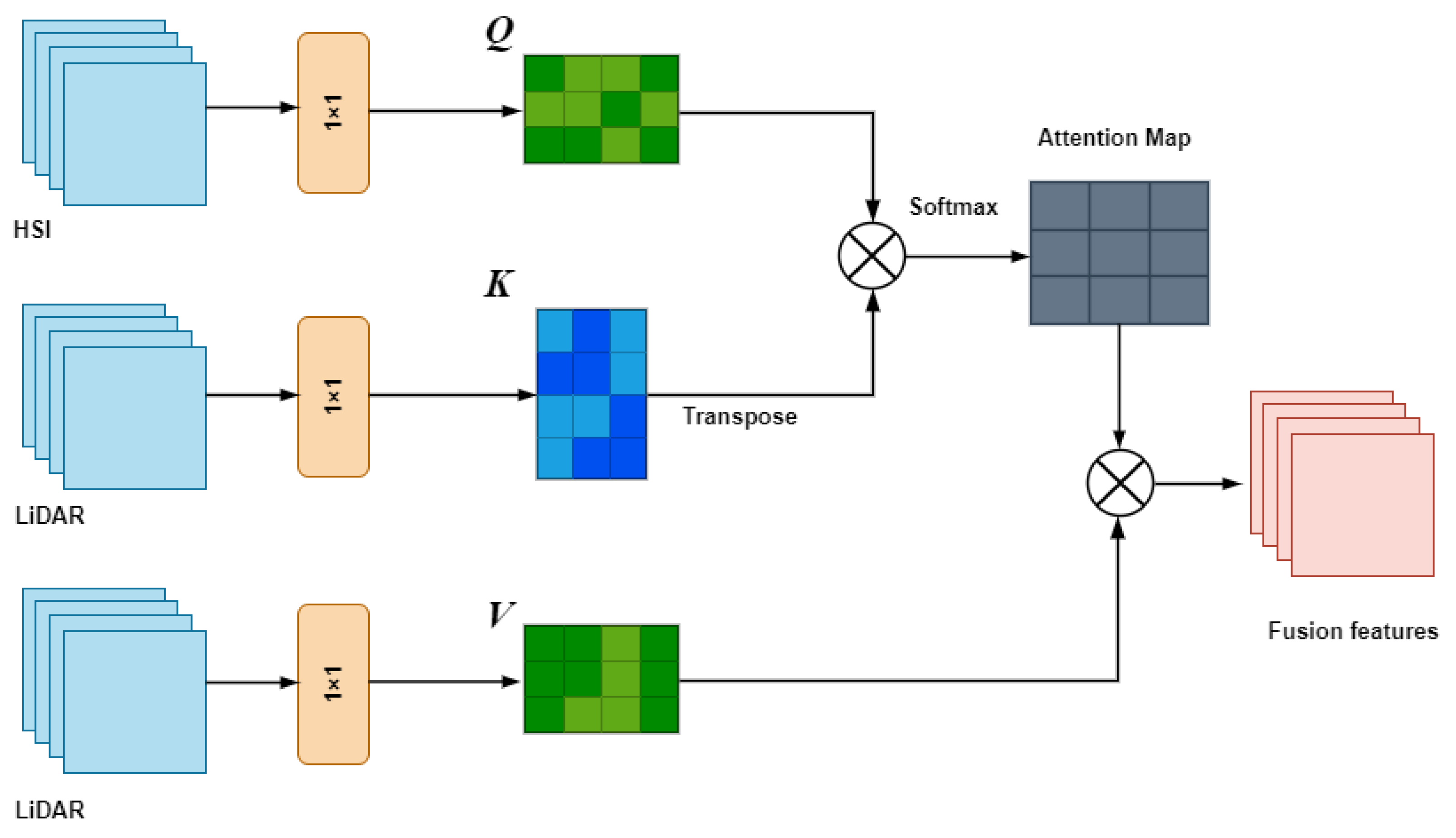

2.5. Cross-Attention Bridge

2.6. Classification

2.7. Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 GL-Mamba Classification Pipeline |

| Require: Hyperspectral image , LiDAR data |

Ensure: Classified map

|

3. Results

3.1. Configuration of Parameters

3.2. Comparison of Patch Size and OA Effects

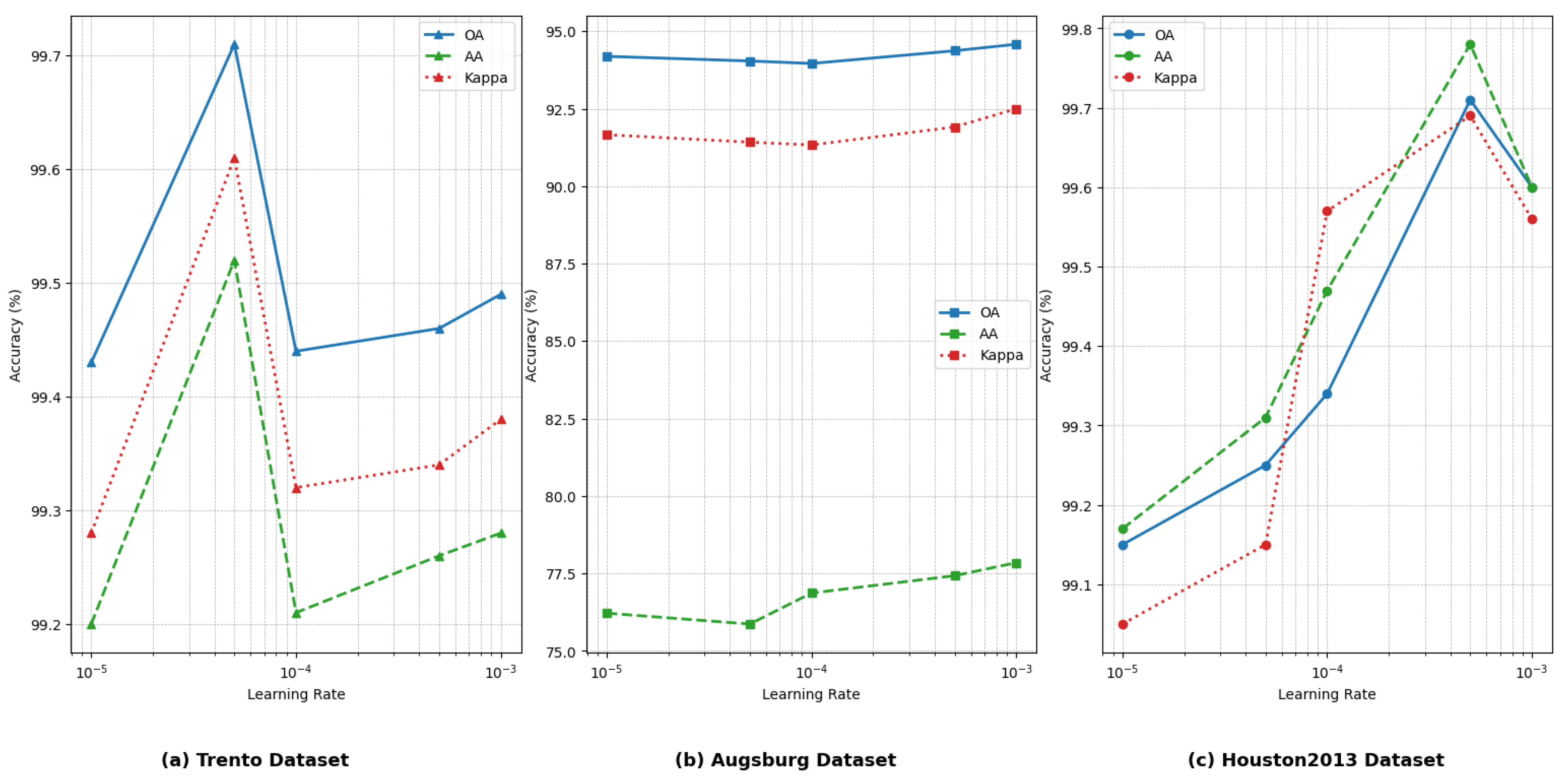

3.3. Comparison of Learning Rate on Datasets

3.4. Comparison and Analysis of Classification Performance

3.4.1. Classification Efficacy on the Trento Dataset

3.4.2. Classification Efficacy on the Augsburg Dataset

3.4.3. Classification Efficacy on the Houston2013 Dataset

3.4.4. Analysis of Class-Specific Limitations

- Commercial-Area in Augsburg (1.83%): This class has extremely limited training samples (only 7 pixels), making it nearly impossible for any deep learning method to learn meaningful representations. All baseline methods also perform poorly on this class, indicating a data scarcity issue rather than a model limitation.

- Industrial-Area in Augsburg (79.03% vs. DSHF’s 87.13%): Industrial areas often contain mixed materials (metal roofs, concrete, vegetation) with high intra-class variability. DSHF’s hierarchical separation may handle such heterogeneity better, while GL-Mamba’s frequency decomposition may over-smooth some distinguishing texture patterns in these complex regions.

- Building in Trento (98.13% vs. S3F2Net’s 99.21%): Buildings adjacent to roads share similar spectral characteristics, and the small accuracy gap (1.08%) reflects inherent ambiguity at class boundaries rather than a fundamental limitation.

3.5. Feature Visualization Analysis

3.6. Computational Efficiency Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Ablation Study

4.2. Impact of Input Modalities

4.3. Impact of Frequency Decomposition

4.4. Impact of GL-Mamba Module

4.5. Impact of Cross-Attention Module

4.6. Summary of Ablation Results

4.7. Isolated Contribution Analysis

- Without GL-Mamba: OA = 99.27% (Trento), 93.10% (Augsburg), 98.58% (Houston)

- With GL-Mamba (no CAM): OA = 99.48%, 93.92%, 99.31%

- Improvement:+0.21%, +0.82%, +0.73%

- Without CAM: OA = 99.48% (Trento), 93.92% (Augsburg), 99.31% (Houston)

- With CAM (full model): OA = 99.71%, 94.58%, 99.60%

- Improvement: +0.23%, +0.66%, +0.29%

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qu, K.; Wang, H.; Ding, M.; Luo, X.; Bao, W. DGMNet: Hyperspectral Unmixing Dual-Branch Network Integrating Adaptive Hop-Aware GCN and Neighborhood Offset Mamba. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Cheng, X.; Lin, S.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H. Memory-Augmented Autoencoder with Adaptive Reconstruction and Sample Attribution Mining for Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5518118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Qu, J.; Dong, W.; Yang, Y. Interpretable Low-Rank Sparse Unmixing and Spatial Attention-Enhanced Difference Mapping Network for Hyperspectral Change Detection. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5526414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.M.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, Y.; Ali, A.; Li, Y. Cross Attention Based Dual-Modality Collaboration for Hyperspectral Image and LiDAR Data Classification. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, S. AFA–Mamba: Adaptive Feature Alignment with Global–Local Mamba for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, J.; Tian, H.; Liew, A.W. LiDAR-Guided Cross-Attention Fusion for Hyperspectral Band Selection and Image Classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03883. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.X.; Wang, J.; Sui, C.H.; Long, Z.; Zhou, J. HSLiNets: Hyperspectral Image and LiDAR Data Fusion Using Efficient Dual Non-Linear Feature Learning Networks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.00302. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, F.; Jin, X.; Zhou, X.; Dong, J.; Du, Q. MSFMamba: Multi-Scale Feature Fusion State Space Model for Multi-Source Remote Sensing Image Classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.14255. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Yu, F.; Zhu, J.; Lu, H. Joint Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Based on Adaptive Gating Mechanism and Learnable Transformer. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, J.; Xie, J.; Wang, Y. Joint Classification of Hyperspectral Images and LiDAR Data Based on Dual-Branch Transformer. Sensors 2024, 24, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Gao, L.; Li, P.; Tao, T. Feature-Decision Level Collaborative Fusion Network for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Classification. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, Q.; Du, Q. Cross-Modal Semantic Enhancement Network for Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5509814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Dai, G.; Li, S.; Liang, X.; Zheng, X. Coupled Adversarial Learning for Fusion Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. Inf. Fusion 2023, 93, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Xu, Y.; Wei, W.; Jia, X.; Xu, Y. A Novel Graph-Attention Based Multimodal Fusion Network for Joint Classification of Hyperspectral Image and LiDAR Data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 249, 123587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, B. Cross Attention-Based Multi-Scale Convolutional Fusion Network for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Joint Classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, Q. Remote Sensing LiDAR and Hyperspectral Classification with Multi-Scale Graph Encoder–Decoder Network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wei, N.; Chen, P.; Su, L.; Dong, Q. Multiscale Adaptive Fusion Network for Joint Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 6594–6634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Chen, T.; Tang, Y.; Li, H.; Guan, P. Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data by Transformer-Based Enhancement. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 15, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Deng, S. Hypergraph Convolution Network Classification for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. Sensors 2025, 25, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taukiri, A.; Pouliot, D.; Rospars, M.; Crawford, G.; McDonough, K.; Glover, S.; Westwood, E. FusionFormer-X: Hierarchical Self-Attentive Multimodal Transformer for HSI–LiDAR Remote Sensing Scene Understanding. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhou, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y. Multi-Feature Cross Attention-Induced Transformer Network for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y. Classification of Hyperspectral–LiDAR Dual-View Data Using Hybrid Feature and Trusted Decision Fusion. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.; Chen, F.; Yao, J.; Du, Q.; Pu, Y. Multimodal Prompt Tuning for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Classification. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, W.; Gong, L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, B. Multiscale Attention Feature Fusion Based on Improved Transformer for Hyperspectral Image and LiDAR Data Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 4124–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, X. Reinforcement Learning Based Markov Edge Decoupled Fusion Network for Fusion Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 7174–7187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zheng, H.; Luo, J.; Fan, L.; Li, H. Learning Unified Anchor Graph for Joint Clustering of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 6341–6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.K.; Krishna, G.; Dubey, S.R.; Chaudhuri, B.B. Cross Hyperspectral and LiDAR Attention Transformer for Multimodal Remote Sensing Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5512815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Meng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Interactive Transformer and CNN Network for Fusion Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 45, 9235–9266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Kang, G.; Li, J.; Gao, X. Local-to-Global Cross-Modal Attention-Aware Fusion for HSI-X Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.17679. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, M.H.F.; Li, J.; Han, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhu, F.; Huang, L. Graph-Infused Hybrid Vision Transformer: Advancing GeoAI for Enhanced Land Cover Classification. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 124, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, S.; Li, Q.; Deng, W.; Li, B. A Comprehensive Survey for Hyperspectral Image Classification in the Era of Deep Learning and Transformers. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.14955. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Hou, C.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G. Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Using Multi-Modal Transformer Cascaded Fusion Net. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Song, J.; Chu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Xia, J. Deep Fuzzy Fusion Network for Joint Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X. Joint Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Based on Heterogeneous Attention Feature Fusion Network. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024—2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7–12 July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaldy, A.; Gloaguen, R.; Fassnacht, F.E.; Ghamisi, P. HyperPointFormer: Multimodal Fusion in 3D Space with Dual-Branch Cross-Attention Transformers. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.23206. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, D.; Wang, Q.; Lai, T.; Huang, H. Joint Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Based on Mamba. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5530915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Zeng, Z.; Gao, C.; Chen, H.; Ma, X. Joint Classification of Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Using Height Information Guided Hierarchical Fusion-and-Separation Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5505315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Song, T.; Ma, X.; Jiu, Y.; Sun, H. Joint Classification of Hyperspectral and Lidar Data Using Cross-Modal Hierarchical Frequency Fusion Network. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 14–19 April 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, R.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification Based on Structural Optimization Transmission. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 3153–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Tao, R. Distribution-Independent Domain Generalization for Multisource Remote Sensing Classification. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 36, 13333–13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debes, C.; Merentitis, A.; Heremans, R.; Hahn, J.; Frangiadakis, N.; Van Kasteren, T.; Liao, W.; Bellens, R.; Pižurica, A.; Gautama, S.; et al. Hyperspectral and LiDAR data fusion: Outcome of the 2013 GRSS data fusion contest. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2014, 7, 2405–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Hang, R.; Zhang, B.; Chanussot, J. Deep encoder–decoder networks for classification of hyperspectral and LiDAR data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2020, 19, 5500205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Hu, J.; Yao, J.; Chanussot, J.; Zhu, X.X. Multimodal remote sensing benchmark datasets for land cover classification with a shared and specific feature learning model. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hong, D.; Chanussot, J. Convolutional neural networks for multimodal remote sensing data classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 5517010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Hong, D.; Chanussot, J. Extended vision transformer (ExViT) for land use and land cover classification: A multimodal deep learning framework. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5514415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Tan, X.; Yu, X.; Liu, B.; Yu, A.; Zhang, P. Deep hierarchical vision transformer for hyperspectral and LiDAR data classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2022, 31, 3095–3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L. SAL2RN: Spectral–And–LiDAR Two-Branch Residual Network for HSI–LiDAR Classification. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, L. MS2CANet: Multiscale Spatial–Spectral Cross-Modal Attention Network for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 5500505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Song, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, X. DSHFNet: Dynamic Scale Hierarchical Fusion Network Based on Multiattention for Hyperspectral Image and LiDAR Data Classification. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 5522514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Song, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, J. S3F2Net: Spatial-Spectral-Structural Feature Fusion Network for Hyperspectral Image and LiDAR Data Classification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 4801–4815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbols | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Original hyperspectral image (HSI) cube and LiDAR raster of the scene | |

| Height and width of the HSI/LiDAR images | |

| B | Number of HSI spectral bands after PCA |

| S | Spatial patch size () |

| C | Number of land-cover classes |

| HSI and LiDAR patches centred at the i-th pixel | |

| Dual-modality input of the i-th sample, | |

| Ground-truth label and predicted class-probability vector of the i-th sample | |

| Low-/high-frequency HSI features (3D CNN/transformer) | |

| Low-/high-frequency LiDAR features (2D CNN/transformer) | |

| Concatenated HSI and LiDAR embeddings after dual-frequency branches | |

| Input feature sequence to the GL-Mamba fusion block at stage s | |

| Fused feature maps after the three GL-Mamba stages | |

| Globally aggregated feature map from all fusion stages | |

| Query, key and value matrices in the cross-attention bridge | |

| Output feature map of the cross-attention module | |

| Predicted spatial offset field for cross-modal alignment | |

| Warping operator that aligns features using the offsets | |

| Cross-entropy loss used for training | |

| Overall accuracy, average accuracy and Kappa coefficient |

| Dataset | Houston2013 [41] | Trento [42] | Augsburg [43] | |||

| Location | Houston, TX, USA | Trento, Italy | Augsburg, Germany | |||

| Sensor Type | HSI | LiDAR | HSI | LiDAR | HSI | LiDAR |

| Image Size | 349 ✕ 1905 | 349 ✕ 1905 | 600 ✕ 166 | 600 ✕ 166 | 332 ✕ 485 | 332 ✕ 485 |

| Spatial Resolution | 2.5 m | 2.5 m | 1 m | 1 m | 30 m | 30 m |

| Number of Bands | 144 | 1 | 63 | 1 | 180 | 1 |

| Wavelength Range | 0.38–1.05 m | / | 0.42–0.99 m | / | 0.4–2.5 m | / |

| Sensor Name | CASI-1500 | / | AISA Eagle | Optech ALTM 3100EA | HySpex | DLR-3K |

| (a) Trento Dataset | ||||||||||

| No. | Class (Train/Test) | CALC | CCR-Net | ExViT | DHViT | SAL2RN | MS2CANet | DSHF | S3F2Net | GL-Mamba |

| 1 | Apple trees (129/3905) | 97.26 | 100.00 | 99.56 | 98.36 | 99.74 | 99.84 | 99.49 | 99.95 | 99.95 |

| 2 | Building (125/2778) | 100.00 | 98.88 | 98.13 | 99.06 | 96.76 | 98.52 | 98.74 | 99.21 | 98.13 |

| 3 | Ground (105/374) | 89.57 | 79.68 | 76.47 | 67.65 | 83.68 | 6.36 | 99.73 | 97.59 | 100.00 |

| 4 | Woods (154/8969) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.21 | 99.98 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| 5 | Vineyard (184/10317) | 99.75 | 94.79 | 99.93 | 98.89 | 99.97 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.96 |

| 6 | Roads (122/3052) | 87.45 | 88.07 | 93.84 | 87.98 | 88.99 | 92.92 | 93.45 | 98.20 | 99.08 |

| OA% | 98.16 | 96.57 | 98.80 | 98.00 | 98.06 | 98.92 | 99.13 | 99.70 | 99.71 | |

| AA% | 95.68 | 93.57 | 94.66 | 92.16 | 94.72 | 96.27 | 98.57 | 99.16 | 99.52 | |

| Kappa ✕ 100 | 97.48 | 95.43 | 98.39 | 97.31 | 97.40 | 98.56 | 98.83 | 99.59 | 99.61 | |

| (b) Augsburg Dataset | ||||||||||

| No. | Class (Train/Test) | CALC | CCR-Net | ExViT | DHViT | SAL2RN | MS2CANet | DSHF | S3F2Net | GL-Mamba |

| 1 | Forest (146/13361) | 94.16 | 93.47 | 91.83 | 90.45 | 96.58 | 96.40 | 97.60 | 98.74 | 99.28 |

| 2 | Residential (264/30065) | 95.32 | 96.86 | 95.38 | 90.87 | 97.69 | 97.90 | 92.94 | 98.24 | 97.22 |

| 3 | Industrial (21/3830) | 86.18 | 82.56 | 43.32 | 61.20 | 53.44 | 48.79 | 87.13 | 78.09 | 79.03 |

| 4 | Low-Plants (248/36609) | 95.57 | 84.45 | 91.13 | 82.82 | 92.84 | 96.47 | 96.38 | 97.59 | 97.58 |

| 5 | Allotment (52/523) | 0.00 | 44.36 | 41.11 | 21.80 | 38.62 | 44.55 | 64.05 | 96.94 | 92.54 |

| 6 | Commercial (7/1638) | 6.05 | 0.00 | 26.01 | 23.50 | 15.14 | 13.43 | 2.50 | 11.90 | 1.83 |

| 7 | Water (23/1507) | 55.96 | 40.48 | 42.07 | 7.43 | 12.47 | 49.90 | 48.77 | 58.33 | 62.57 |

| OA% | 91.46 | 87.82 | 87.82 | 83.06 | 89.85 | 91.65 | 91.67 | 94.50 | 94.58 | |

| AA% | 61.89 | 63.17 | 61.41 | 54.01 | 58.11 | 63.92 | 69.91 | 77.12 | 77.85 | |

| Kappa ✕ 100 | 88.04 | 82.48 | 82.44 | 75.91 | 85.26 | 88.22 | 88.12 | 92.10 | 92.50 | |

| (c) Houston2013 Dataset | ||||||||||

| No. | Class (Train/Test) | CALC | CCR-Net | ExViT | DHViT | SAL2RN | MS2CANet | DSHF | S3F2Net | GL-Mamba |

| 1 | Healthy grass (198/1053) | 94.64 | 94.64 | 82.24 | 85.15 | 91.55 | 81.01 | 82.62 | 85.75 | 99.72 |

| 2 | Stressed grass (190/1064) | 94.51 | 94.64 | 83.93 | 84.87 | 90.85 | 89.51 | 93.47 | 96.71 | 99.44 |

| 3 | Synthetic grass (192/506) | 89.37 | 79.47 | 82.99 | 79.76 | 92.87 | 99.67 | 99.91 | 95.84 | 99.68 |

| 4 | Trees (188/1056) | 96.25 | 90.71 | 88.90 | 92.91 | 96.47 | 94.50 | 99.91 | 98.20 | 99.91 |

| 5 | Soil (188/1056) | 96.25 | 94.01 | 90.85 | 92.61 | 96.40 | 93.88 | 100.00 | 99.71 | 100.00 |

| 6 | Water (162/143) | 96.25 | 91.47 | 92.21 | 94.36 | 94.72 | 92.12 | 100.00 | 97.90 | 99.92 |

| 7 | Residential (196/1072) | 97.00 | 92.98 | 91.50 | 95.93 | 94.24 | 92.58 | 97.90 | 95.24 | 99.70 |

| 8 | Commercial (191/1053) | 95.53 | 93.53 | 94.03 | 94.72 | 92.61 | 91.91 | 100.00 | 95.34 | 99.62 |

| 9 | Road (193/1063) | 91.54 | 92.87 | 92.33 | 91.90 | 94.83 | 94.56 | 99.32 | 96.31 | 99.59 |

| 10 | Highway (191/1054) | 92.77 | 93.35 | 95.40 | 91.38 | 89.57 | 94.77 | 99.32 | 81.85 | 99.65 |

| 11 | Railway (181/1062) | 93.63 | 91.75 | 91.09 | 93.47 | 94.50 | 95.58 | 100.00 | 97.62 | 100.00 |

| 12 | Parking lot 1 (190/1054) | 91.09 | 89.64 | 91.71 | 93.22 | 91.50 | 92.75 | 99.60 | 98.46 | 99.74 |

| 13 | Parking lot 2 (119/1047) | 94.45 | 87.86 | 91.57 | 92.21 | 90.51 | 93.04 | 99.52 | 94.38 | 99.65 |

| 14 | Tennis court (181/247) | 95.36 | 97.06 | 95.55 | 91.52 | 95.06 | 96.52 | 100.00 | 95.14 | 100.00 |

| 15 | Running track (187/473) | 97.09 | 99.86 | 97.62 | 99.12 | 97.62 | 96.61 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.95 |

| OA% | 91.07 | 88.88 | 85.72 | 90.66 | 89.83 | 92.88 | 91.67 | 94.50 | 99.60 | |

| AA% | 91.20 | 91.24 | 87.09 | 91.15 | 90.50 | 91.02 | 92.50 | 91.76 | 99.68 | |

| Kappa ✕ 100 | 89.89 | 87.87 | 89.52 | 88.46 | 90.42 | 90.87 | 92.91 | 92.27 | 99.56 | |

| CCR-Net | CALC | ExViT | DHViT | SAL2RN | MS2CANet | DSHF | S3F2Net | Proposed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Params (K) | 70.08 | 284.14 | 229.10 | 3737.71 | 940.79 | 180.02 | 312.45 | 425.38 | 275.20 |

| FLOPs (M) | 0.14 | 28.75 | 46.87 | 322.52 | 6.32 | 2.23 | 18.64 | 32.17 | 57.50 |

| Training time (s) | 61.12 | 563.14 | 323.86 | 472.35 | 163.70 | 115.77 | 198.42 | 245.63 | 688.64 |

| Test time (s) | 0.06 | 2.04 | 4.27 | 5.81 | 1.78 | 1.56 | 1.82 | 2.35 | 2.07 |

| Components | Metrics | Datasets | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSI | LiDAR | Low-Freq | High-Freq | GL-Mamba | CAM | Trento | Augsburg | Houston2013 | |

| ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | OA (%) | 98.98 | 93.79 | 98.88 | |

| AA (%) | 99.22 | 75.44 | 98.19 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 98.90 | 91.06 | 98.50 | ||||||

| ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | OA (%) | 87.23 | 78.45 | 83.67 |

| AA (%) | 84.56 | 62.31 | 81.24 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 85.12 | 72.89 | 81.45 | ||||||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | OA (%) | 97.83 | 91.24 | 97.12 |

| AA (%) | 96.45 | 71.56 | 96.34 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 97.21 | 88.45 | 96.78 | ||||||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | OA (%) | 96.45 | 89.67 | 95.89 |

| AA (%) | 95.12 | 68.92 | 94.56 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 95.78 | 86.23 | 95.12 | ||||||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | OA (%) | 99.27 | 93.10 | 98.58 |

| AA (%) | 99.67 | 77.12 | 99.02 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 99.54 | 92.10 | 99.50 | ||||||

| ✓ | ✕ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | OA (%) | 99.16 | 93.23 | 99.18 |

| AA (%) | 98.51 | 76.37 | 99.10 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 99.14 | 90.12 | 99.11 | ||||||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | OA (%) | 99.48 | 93.92 | 99.31 |

| AA (%) | 99.34 | 77.45 | 99.42 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 99.45 | 91.78 | 99.28 | ||||||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | OA (%) | 99.71 | 94.58 | 99.60 |

| AA (%) | 99.52 | 77.85 | 99.68 | ||||||

| Kappa (%) | 99.61 | 92.69 | 99.56 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hussain, K.M.; Zhao, K.; Pervaiz, S.; Li, Y. Global–Local Mamba-Based Dual-Modality Fusion for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010138

Hussain KM, Zhao K, Pervaiz S, Li Y. Global–Local Mamba-Based Dual-Modality Fusion for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010138

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussain, Khanzada Muzammil, Keyun Zhao, Sachal Pervaiz, and Ying Li. 2026. "Global–Local Mamba-Based Dual-Modality Fusion for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010138

APA StyleHussain, K. M., Zhao, K., Pervaiz, S., & Li, Y. (2026). Global–Local Mamba-Based Dual-Modality Fusion for Hyperspectral and LiDAR Data Classification. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010138