1. Introduction

As the world’s highest and most extensive plateau, the Tibetan Plateau (TP) functions as a massive “aerial heat source”, profoundly influencing the Asian climate [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. It exerts profound influences on the Asian summer monsoon system through intense thermal and dynamic forcing [

6]. Numerous studies have confirmed the crucial role of plateau surface sensible heat flux (SHF) in driving anomalies in the surrounding atmospheric circulation and modulating the Asian summer monsoon [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The thermal effects of the plateau, by altering atmospheric circulation, moisture transport, and energy balance, not only regulate weather and climate over the plateau and its adjacent regions but also impact broader-scale climate systems via atmospheric teleconnections [

12,

13,

14]. However, TP surface energy partitioning is highly heterogeneous: moisture-rich sectors tend to favor latent heat flux associated with evapotranspiration/sublimation, whereas dry interior sectors favor sensible heating. As a result, domain-mean SHF alone may not fully represent the spatially heterogeneous thermal forcing experienced by the atmosphere.

Despite the recognized importance of TP thermal forcing, substantial debate remains regarding the dominant mechanisms by which the plateau influences the monsoon system. Some studies emphasize TP sensible heating as a key driver of the Asian summer monsoon [

15,

16,

17,

18], whereas others argue that summertime heating over the plateau interior is weaker than that over adjacent lowland regions (e.g., northern India), implying a potentially limited role of plateau heating and highlighting instead the importance of the TP’s dynamical blocking effect [

19,

20,

21]. This comparison suggests a potentially limited thermal influence of the plateau itself on the monsoon, leading these studies to highlight instead the importance of the plateau’s dynamic blocking effect. This disagreement partly stems from limitations of traditional indicators, such as SHF, in accurately characterizing the plateau’s thermal forcing. For instance, the SHF over the TP peaks in spring, whereas summer monsoon precipitation reaches its maximum in summer, indicating a noticeable phase difference in their annual cycles [

22].

In the process through which thermal forcing influences the monsoon system, cloud feedback mechanisms play a complex and critical role. The interaction among clouds, radiation, and thermal forcing constitutes an important feedback pathway. Specifically, the unique cloud systems over the TP significantly affect the thermal conditions and hydrological cycle of the plateau by modifying the surface radiation balance [

23,

24]. By modifying the surface radiation budget, clouds can regulate boundary-layer development and the partitioning of available energy into sensible versus latent heat fluxes. For instance, cloud-induced shortwave shading can reduce surface solar heating, whereas longwave effects can offset part of the radiative cooling; the net impact may depend on cloud vertical structure and background surface moisture conditions [

25,

26,

27]. Therefore, cloud impacts on TP “heat pump”-related processes are expected to be cloud-type- and regime-dependent rather than uniform in their effects.

Although previous studies have examined TP thermal forcing and cloud effects, an integrated understanding of their dynamic coupling and their roles in monsoon variability remains limited. First, many existing analyses focus on synchronous relationships, potentially overlooking lead–lag structures among cloud feedback, surface energy partitioning, and monsoon intensity. Second, clouds at different vertical levels (high, mid-level, and low) can respond differently to changes in circulation and moisture and can influence the surface energy balance through distinct physical pathways. However, research on this aspect has been hampered by significant underestimation of low clouds over the TP in earlier cloud classification algorithms. The algorithm proposed by Bao et al. [

28] effectively mitigates this limitation, and this study utilizes the long-term cloud-type product generated using their method.

To address these gaps, this study employs multi-source observations and reanalysis data to systematically investigate the interactions among TP thermal forcing, cloud feedbacks, and the Asian summer monsoon. Specifically, we aim to (1) characterize the spatiotemporal evolution of different cloud types and key climatic variables over the TP; (2) quantify the lead–lag relationships between high cloud cover (HCC) and these variables; (3) elucidate the sequence of interactions between HCC and surface energy/water cycle components; and (4) synthesize the results into an integrated physical framework that illustrates how TP thermal forcing and cloud feedbacks jointly modulate the monsoon system. This research will advance the understanding of plateau land–atmosphere interactions and provide a scientific basis for improving the parameterization of cloud–radiation–thermal processes in climate models, thereby enhancing the simulation and prediction of the Asian summer monsoon.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

The cloud parameters used in this study—cloud optical thickness, cloud-top temperature, and cloud amount—were obtained from the CERES Synoptic 1° (SYN1deg) Level-3 product (Edition 4.1; 1-h; 1° × 1°). This dataset provides gridded cloud-property fields derived primarily from MODIS (and GEO-enhanced) observations [

29] and is widely used in climate studies [

29,

30]. All data are publicly accessible through the NASA CERES platform (

https://ceres.larc.nasa.gov/data/; accessed on 15 October 2025). These CERES cloud properties serve as the observational basis for constructing the long-term cloud-type dataset over the TP using the enhanced classification approach described in

Section 2.2.

This study also uses ERA5, the fifth-generation atmospheric reanalysis from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), utilizing monthly mean data from the Copernicus Climate Data Store. Specifically, surface variables (including surface latent heat flux, sensible heat flux, and surface radiative fluxes) were obtained from the ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to the present for the period 2001–2023 over the TP.

We used surface latent heat flux (LHF) and sensible heat flux (SHF) to examine land–atmosphere interactions. According to the ECMWF convention, vertical fluxes are positive downward; therefore, negative LHF/SHF indicates an upward heat transfer from the surface to the atmosphere. For clarity and consistency with the land–atmosphere coupling interpretation, LHF and SHF were multiplied by −1 so that positive values represent upward fluxes (i.e., heat transfer from the surface to the atmosphere).

For the surface radiation budget and cloud radiative forcing (CRF), we used ERA5 monthly mean surface net shortwave radiation flux and mean surface net longwave radiation flux, along with their clear-sky counterparts (units: W m−2).

The all-sky surface net radiation was calculated by adding the net shortwave and net longwave components, while the clear-sky net radiation was calculated similarly using the clear-sky fields. Surface CRF was determined as the difference between all-sky and clear-sky fluxes for each element (shortwave and longwave), and the net CRF was subsequently derived from the difference in net radiation.

In contrast, upper-air circulation and moisture fields were derived from monthly-averaged ERA5 pressure-level data from 1940 to the present. Specifically, the wind field (u- and v-components), geopotential height, specific humidity, and the divergence-related diagnostics used to define and diagnose the TPMI and circulation anomalies were based on the pressure-level monthly mean dataset. Wind divergence was calculated from the u- and v-wind components at the relevant pressure level(s) to ensure consistency with the wind field used in circulation analysis. For the comparative case studies of 2012 and 2022, we further examined u- and v-wind components, geopotential height, and specific humidity from the same pressure-level dataset. To address the spatial-resolution mismatch between CERES (1°) and ERA5 (0.25°) in joint analyses, fields were regridded to a common grid before conducting spatial diagnostics (e.g., mapping, correlation, and composite analyses) [

31].

2.2. Cloud Classification Method

To create a long-term cloud-type dataset over the TP, we applied an improved classification method developed by Bao et al. [

28] to process CERES satellite data from 2001 to 2023. This method uses cloud microphysical features to achieve more accurate cloud classification than traditional approaches. Compared with conventional ISCCP algorithms, this approach demonstrates significantly improved ability to detect low clouds and effectively addresses the systematic overestimation of high clouds observed in earlier datasets.

The traditional ISCCP cloud classification method usually depends on cloud-top pressure thresholds to identify high, mid-level, and low clouds. However, in the TP region, where the average elevation exceeds 4000 m, this approach has significant limitations—because of the much lower surface pressure over the plateau, applying standard global pressure thresholds (e.g., high cloud: <440 hPa; mid-level cloud: 440–680 hPa; low cloud: >680 hPa) results in systematic misclassification. Specifically, many mid-level and low clouds are misclassified as high clouds, and the amount of low clouds is substantially underestimated.

To address this issue, the new algorithm improves cloud classification by shifting the criterion from “cloud-top pressure” to “cloud-top temperature”. Specifically, the pressure thresholds from the ISCCP standard are converted into corresponding altitudes based on the pressure–height relationship, and then, the corresponding temperature thresholds are calculated using the temperature–height formula along with the average elevation of the plateau. By adopting temperature—a variable more closely linked to cloud microphysical processes—this adjustment effectively corrects the systematic bias caused by the low-pressure environment over the TP.

Compared with the traditional ISCCP algorithm, which relies on cloud-top pressure, the present method significantly enhances the detection of low clouds over the plateau while reducing the systematic overestimation of high clouds, thereby providing a more reliable data foundation for studying cloud–radiation effects over the TP.

2.3. Definition of TP Monsoon Index

The TP Monsoon Index (TPMI) used in this study is derived from the 600 hPa divergence field, following the method proposed by Zhou et al. [

32]. This approach relies on the distinct seasonal reversal of divergence between winter and summer, providing a clear physical explanation for the monsoon mechanism over the plateau. To define this circulation index, the core region of the plateau (30°N–35°N, 80°E–100°E) was selected because it shows the most prominent negative anomaly center in the long-term average divergence field during summer. The TPMI is defined as the seasonal mean divergence averaged over this region.

It is essential to distinguish the purposes of these geographical regions: The aforementioned core region is used solely to calculate the TPMI time series. In contrast, all subsequent spatial analyses (such as cloud cover and surface energy fluxes) and lead–lag correlation analyses between these variables and the TPMI are performed across the entire TP. The plateau area is defined as regions with elevations exceeding 2500 m, roughly spanning 26–40°N and 73–105°E [

33]. The boundary of this entire TP domain is outlined by the black lines in the spatial distribution maps (as shown in

Section 3.1). According to the definition, negative TPMI values represent convergent flow in the lower troposphere over the central plateau, with larger negative values indicating a stronger summer monsoon. Conversely, positive values denote divergent flow, with larger positive values indicating a stronger winter monsoon. As our emphasis is on monsoon intensity, the subsequent analyses use the absolute magnitude of TPMI (|TPMI|) to quantify monsoon strength.

2.4. Definition of Moisture Transport and Moisture Flux Vector

Moisture transport in this study is calculated from the horizontal wind and specific humidity fields, based on the fundamental physical principle governing the transport of atmospheric water vapor. This approach is grounded in the fact that moisture transport is the primary process responsible for the redistribution of atmospheric water vapor, which directly determines the formation and distribution of precipitation [

34].

The core variable, the horizontal moisture flux vector

Q, is defined as the product of the horizontal wind vector (

V) and the specific humidity (q) [

35]. The moisture flux vector is defined as

According to this definition, the moisture flux is a vector. Its magnitude (|

Q|) indicates the strength of the transport, while its direction indicates the pathway of water vapor flow. Larger flux magnitudes indicate stronger moisture transport, often linked to increased precipitation downwind.

2.5. Statistical Methods

Linear regression is a key statistical modeling method used to measure the quantitative relationship between one or more independent variables (X) and a dependent variable (Y). By fitting an optimal line (or hyperplane) that minimizes the sum of squared residuals (i.e., the least-squares method), this technique yields coefficients that indicate the strength and direction of the relationships, revealing underlying associations [

36,

37,

38]. In this study, simple linear regression was conducted with the year as the independent variable to assess the long-term trends (2001–2023) of the following dependent variables: HCC, mid-level cloud cover (MCC), low cloud cover (LCC), the TP Monsoon Index (TPMI), latent heat flux (LHF), and sensible heat flux (SHF). The slope of each regression line, reflecting the trend coefficient, indicates the rate and direction of interannual variation.

To evaluate the reliability of the multi-year monthly averages, we calculated the standard deviation for each month as an indicator of uncertainty. For month m with N annual samples, the standard deviation σₘ is determined as

where

denotes the value for month m in year I, and

is the multi-year mean for that month [

39]. In the analysis discussed in

Section 3.2, the error-bar length corresponds to ±

. Longer error bars indicate that the multi-year mean for that month is more strongly influenced by interannual variability. In contrast, shorter error bars suggest that the multi-year mean is relatively stable.

To further explore the dynamic temporal relationships between plateau cloud cover and monsoon indices as well as LHF and SHF, this study uses a lead–lag correlation analysis. This statistical method is commonly applied in climate research, particularly for analyzing variables with clear seasonal cycles and year-to-year changes, because it systematically uncovers interaction patterns between two variables across multiple time scales and can reveal lead–lag relationships [

40,

41]. The main idea behind lead–lag correlation analysis is to introduce a time lag τ and calculate correlation coefficients between two time series at different relative time offsets to determine their leading–response relationship [

42]. Specifically, we define the lagged correlation at lag k months as

where negative k indicates that cloud cover leads the target variable by ∣k∣ months, and positive k suggests that cloud cover lags the target variable by k months. Correlations were computed for k = −12 to +12 months using deseasonalized and linearly detrended anomalies, and significance was assessed using a

t-test with an effective degrees-of-freedom adjustment for autocorrelation. Specifically, the linear detrending was performed by fitting a least-squares linear regression to the deseasonalized time series of each variable and then subtracting this long-term linear trend. This process removes the potential spurious correlation caused by shared long-term climate change signals, thereby ensuring that the subsequent lead–lag correlation analysis focuses on interannual variability [

43].

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Patterns of Cloud Cover and Surface Energy Fluxes

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

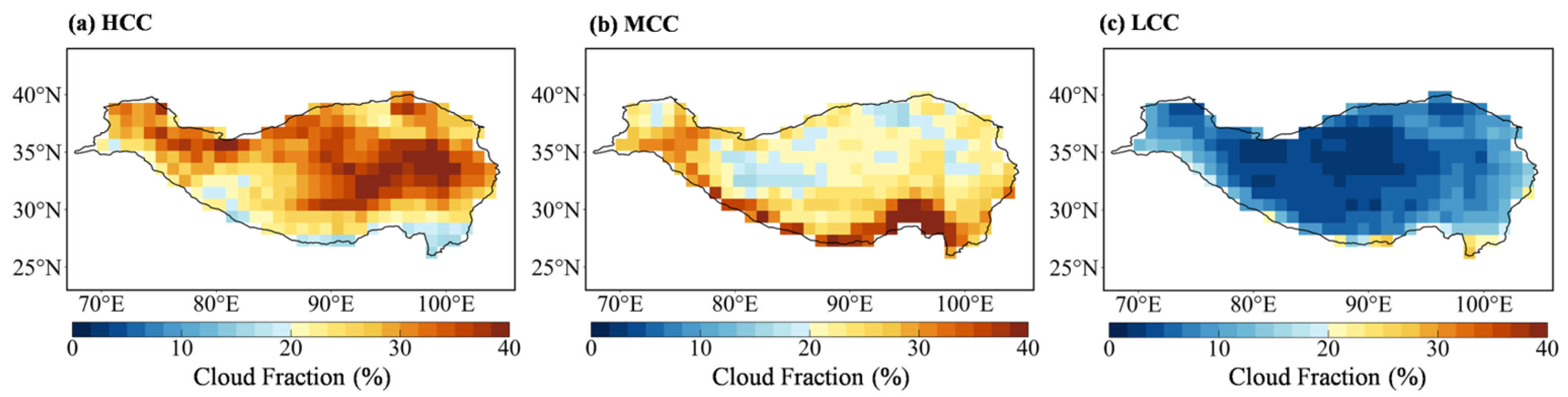

Figure 3 show the 2001–2023 climatological spatial patterns of cloud vertical distribution and key components of the surface energy balance over the TP, including all-sky surface radiative fluxes, CRF, and heat fluxes. These multi-year averages provide a baseline overview of where clouds typically form and how they influence surface radiative heating and cooling as well as the allocation of available energy into latent and sensible heat. Overall, the TP is characterized by high clouds, the most common layer; a radiative signature of positive longwave CRF and negative shortwave CRF; and notable regional differences in heat fluxes.

HCC (

Figure 1a) is widespread across the TP, with enhanced values over the central–eastern and northeastern plateau (typically ~30–40%), while relatively lower values occur along parts of the southern margin. Mid-level cloud cover (MCC;

Figure 1b) is markedly enhanced along the south and southeastern margins (locally approaching ~30–40%), consistent with more vigorous synoptic activity and orographic lifting near the plateau’s topographic boundaries. Low cloud cover (LCC;

Figure 1c) remains generally limited over the plateau interior, with comparatively higher values mainly confined to the eastern/southeastern edges. Overall, the southeast-to-northwest contrast in cloud occurrence is consistent with the well-known moisture supply and topographic control over TP hydroclimate [

44]. This spatial pattern agrees with earlier ground- and satellite-based assessments of TP cloudiness. This southeast–northwest gradient aligns with stronger moisture transport and/orographic lifting along the southern and southeastern margins compared with the drier northwestern interior.

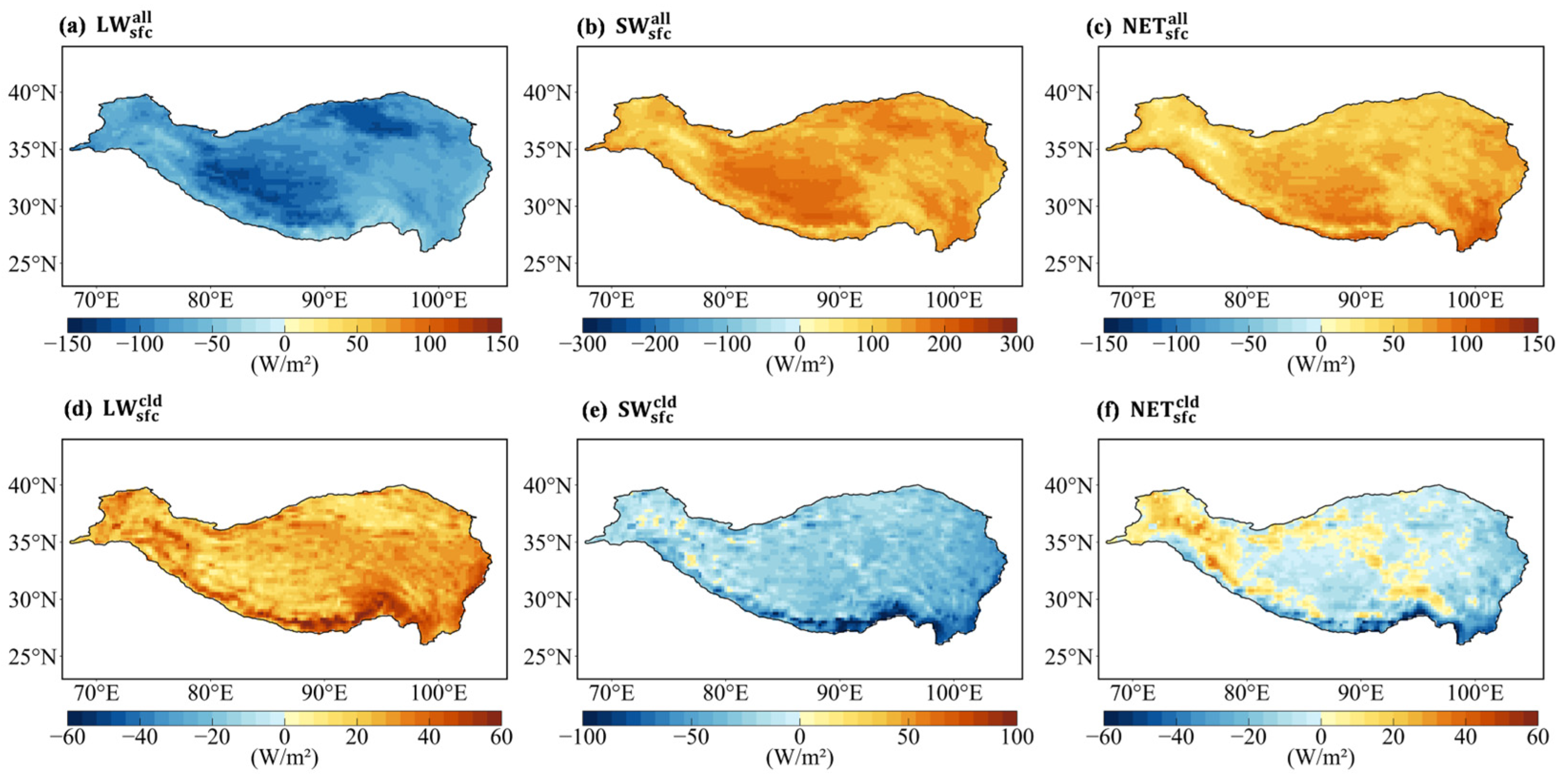

The all-sky surface net longwave radiation (

;

Figure 2a) is negative across the TP, reflecting persistent longwave cooling of the surface. The all-sky surface net shortwave radiation (

;

Figure 2b) is positive and spatially coherent, indicating that absorbed solar radiation is the primary energy input. Consequently, the net radiation (

;

Figure 2c) is predominantly positive over most of the TP.

The CRF patterns show a clear compensation between longwave warming and shortwave cooling. Specifically,

(

Figure 2d) is positive over most areas. In contrast,

(

Figure 2e) is negative and generally larger in magnitude, leading to a predominantly negative

(

Figure 2f). Regions with more frequent cloud occurrence (notably along the southern/southeastern margins in

Figure 1) tend to exhibit stronger shortwave cooling and thus more negative net CRF, highlighting the first-order control of cloudiness on cloud-induced surface radiative perturbations [

45]. The pronounced contrast between LHF and SHF suggests that land-surface hydrological constraints, in addition to radiative effects, regulate energy exchange over the TP [

46].

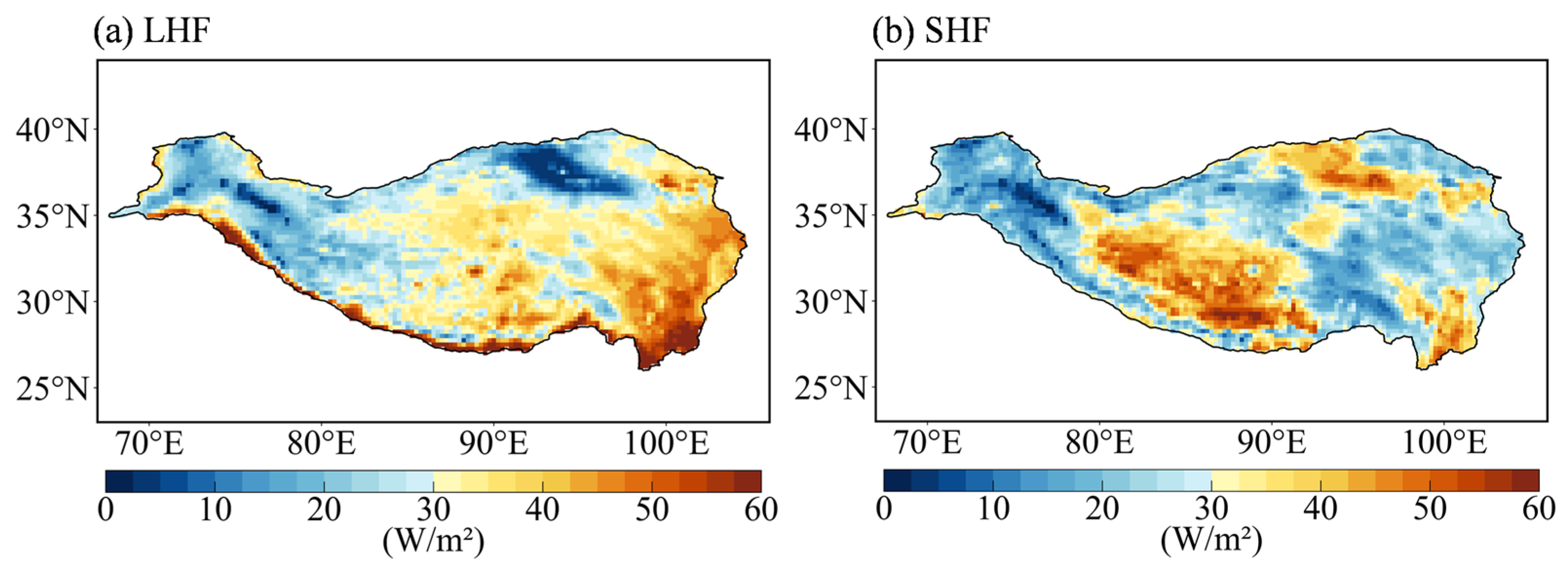

The multi-year mean latent heat flux (LHF;

Figure 3a) exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity, with relatively larger values over the eastern and southeastern TP, consistent with greater surface moisture availability and stronger evapotranspiration. Notably, in this study, surface LHF and SHF follow the ERA5 sign convention, with positive values indicating upward fluxes from the land surface to the atmosphere. Accordingly, positive SHF represents surface heating of the lower atmosphere, while positive LHF reflects enhanced surface evaporation and moisture transfer. Sensible heat flux (SHF;

Figure 3b) is enhanced over the central–western TP and other relatively dry regions, indicating a shift in surface energy partitioning toward sensible heating under moisture-limited conditions. The marked contrast between LHF and SHF further indicates that land-surface moisture availability is one of the key factors regulating surface–atmosphere energy exchange.

Overall, the southeastern TP features higher cloud occurrence, stronger shortwave cloud shading (more negative ), and larger LHF, consistent with a moisture-rich regime. In contrast, the drier central–western TP exhibits weaker cloud radiative damping and enhanced SHF, indicating a shift toward sensible heating under moisture limitation.

3.2. Seasonal Cycle Characteristics of Cloud Cover and Climate Variables

To further understand the temporal evolution of these key elements, we focus on analyzing the characteristics of their climatological mean seasonal cycles in this section.

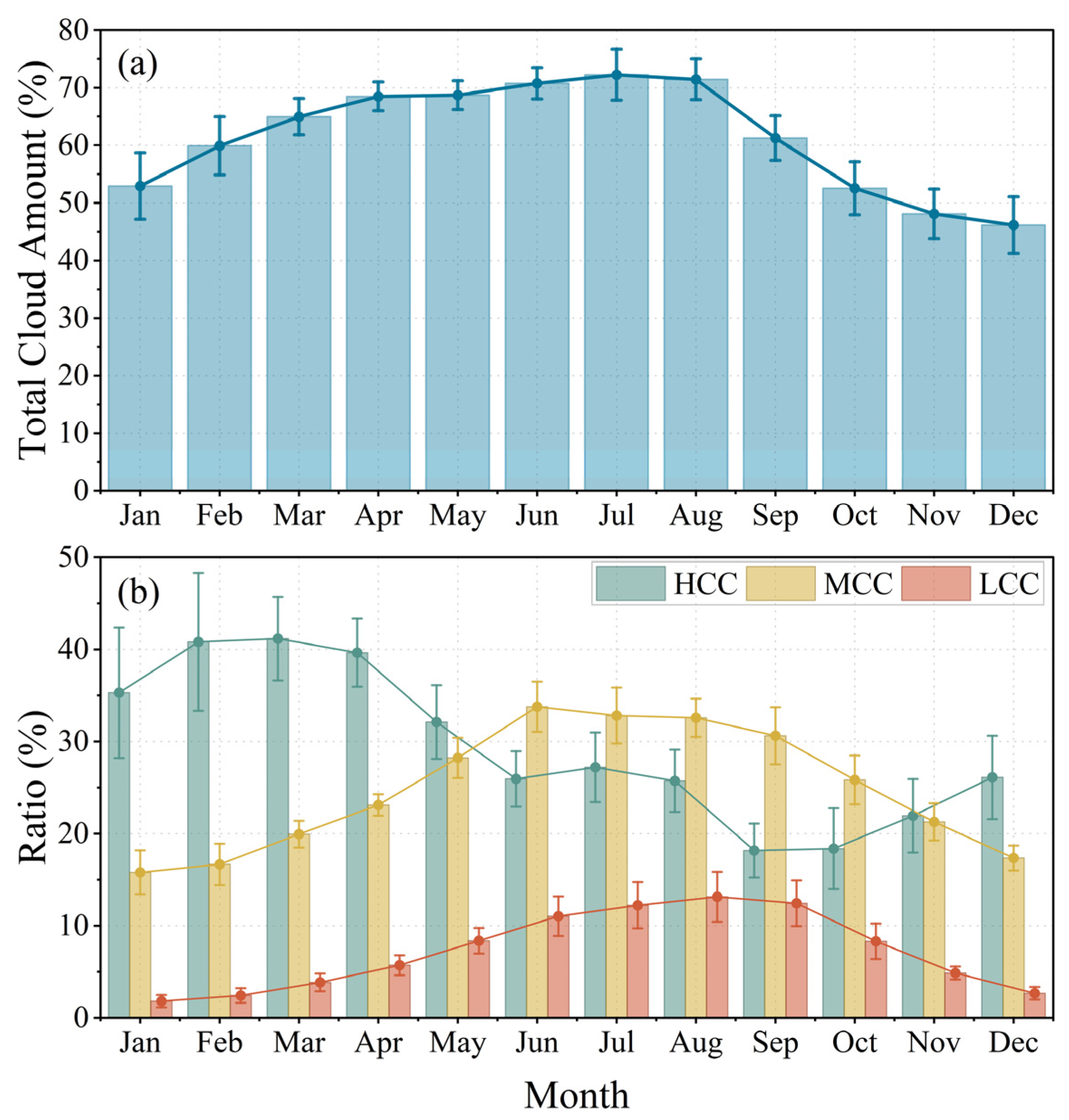

Total cloud cover (TCC) exhibits a pronounced annual cycle (

Figure 4a), increasing from winter (~45–55% in December–January) to a summer maximum (~70–75% in July–August), followed by a rapid decline during autumn (September–November). The cloud-type composition varies systematically through the year (

Figure 4b). HCC dominates in the cold season and early spring, reaching its highest contribution in late winter–early spring (February–March; ~40%), and decreases markedly through summer (September minimum ~18–20%). In contrast, MCC increases from spring to summer, peaking during the warm season (June–August; ~32–35%) and then weakening toward winter. LCC remains the minor contributor year-round but shows a clear warm-season enhancement, rising from ~2–4% in winter to ~10–13% in July–September Notably, the transition from HCC-dominant conditions to enhanced MCC/LCC occurs in late spring to early summer (around May–June), consistent with a seasonal shift in cloud vertical structure toward greater mid- to low-level cloudiness during the warm season.

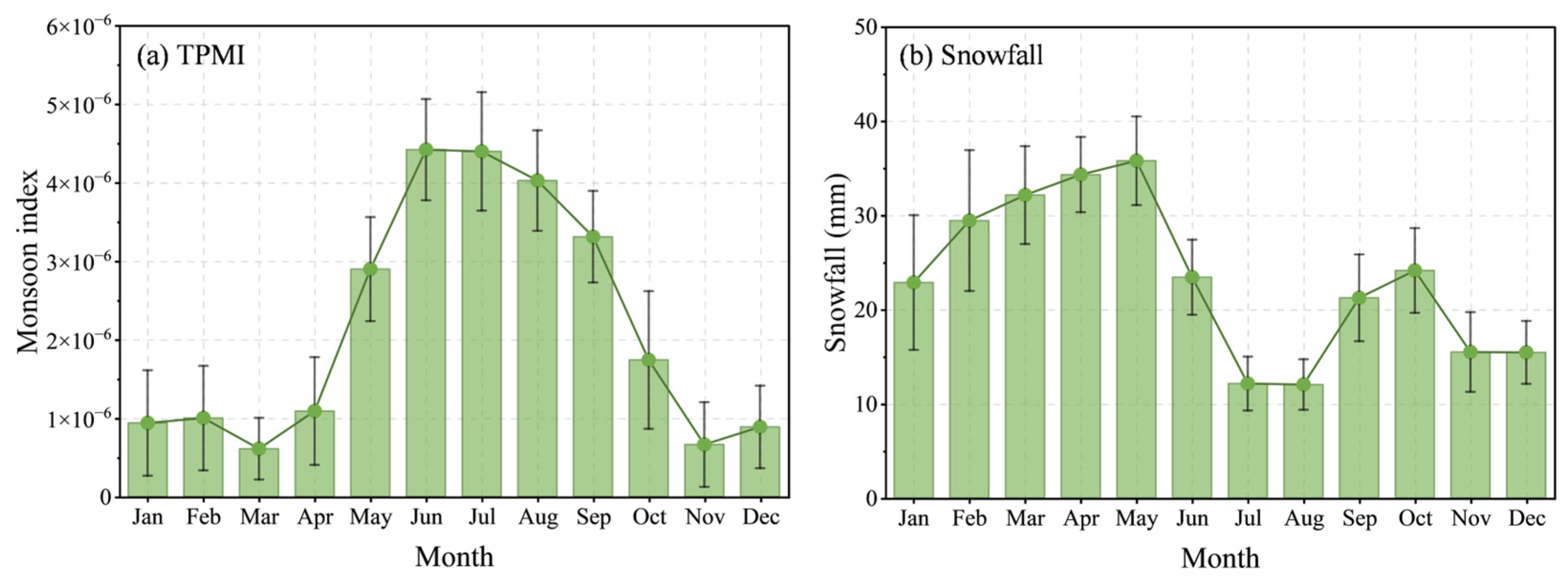

TPMI exhibits a pronounced seasonal cycle (

Figure 5a), increasing rapidly from April to May and reaching its maximum in early summer (June–July), remaining relatively high through August–September, and then declining sharply in autumn to low values in late autumn–winter (November–March). The interannual variability is most evident during the peak monsoon season (approximately June–August), as indicated by the larger error bars. In contrast, snowfall shows a distinct phase (

Figure 5b) characterized by a spring maximum (March–May; peak around May), a pronounced minimum in midsummer (July–August), and a secondary enhancement in early autumn (September–October). The differing seasonal phasing between TPMI and snowfall indicates that TP monsoon-related circulation and snowfall variability are not synchronous, highlighting strong seasonality in the dynamical and thermodynamical controls on precipitation over the TP.

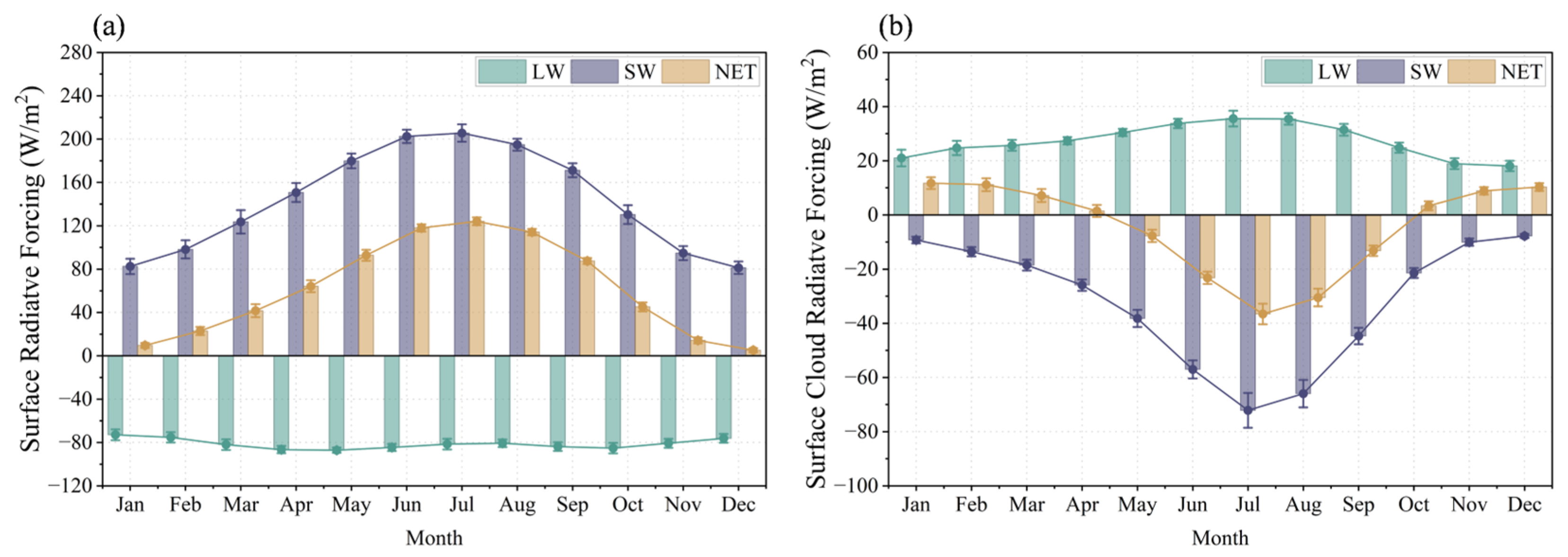

The all-sky surface radiation components exhibit a canonical seasonal cycle driven primarily by shortwave variability (

Figure 6a).

increases from winter to summer, reaching a maximum in early to mid-summer (June–July), and decreases thereafter. In contrast,

remains negative year-round with comparatively weak seasonality. As a result,

is positive throughout the year and peaks in summer (June–August), closely following the seasonal evolution of

.

The surface CRF fields (

Figure 6b) show a clear seasonal compensation.

is positive in all months and maximizes in summer, indicating enhanced cloud longwave warming under warmer and cloudier conditions.

is negative year-round, intensifying strongly in late spring and summer when insolation is strongest, and cloud shading is most effective. Consequently,

exhibits a seasonal sign reversal: it is weakly positive in winter (cloud longwave warming slightly outweighs shortwave cooling). Still, it becomes substantially negative in summer (shortwave cooling dominates), with the most negative values occurring in July–August.

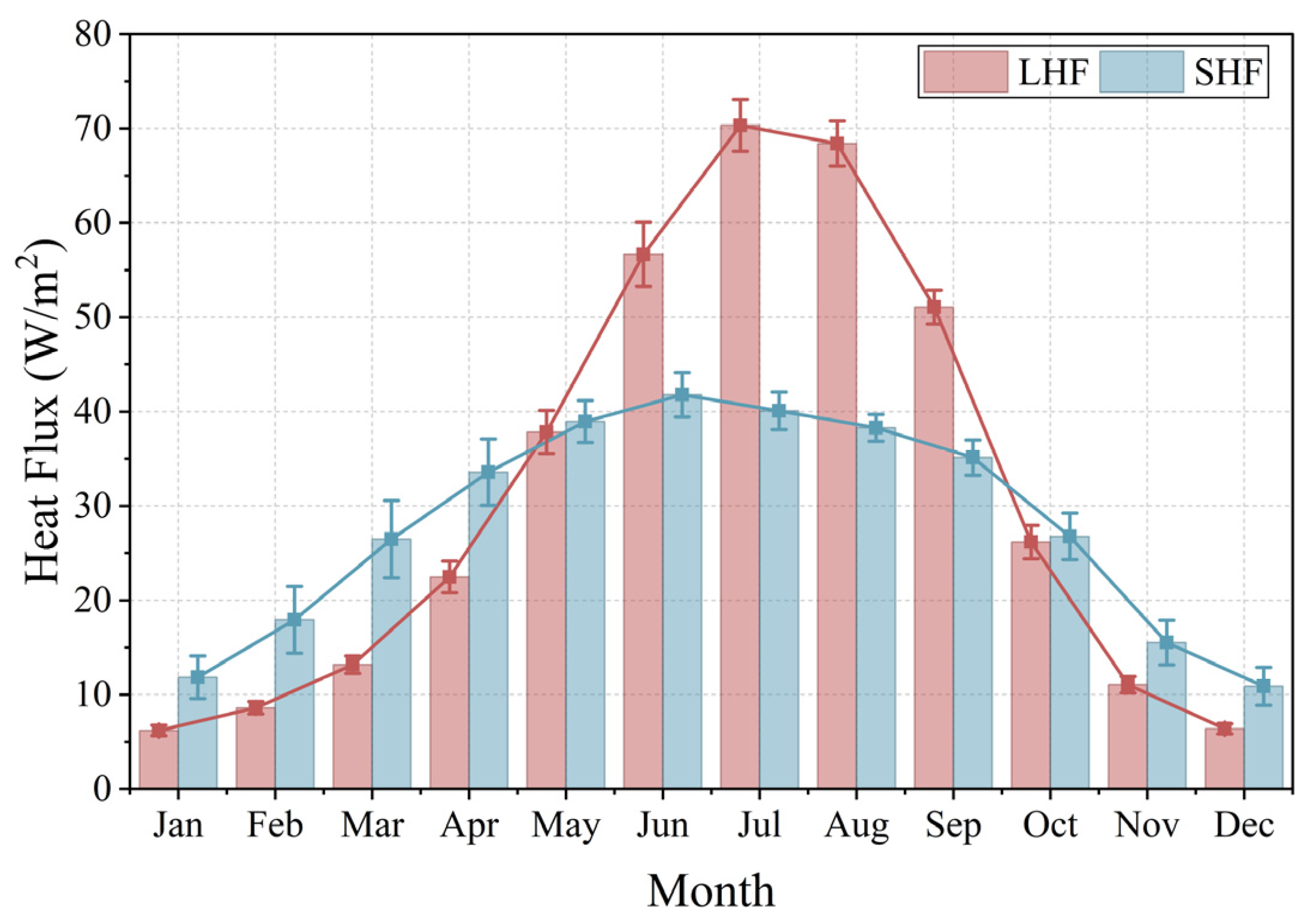

Both SHF and LHF show a strengthening trend from winter to summer (

Figure 7), though their evolution patterns differ. Specifically, SHF increases steadily from winter, peaks in early to mid-summer (around July), and then gradually weakens during autumn. In contrast, LHF rises rapidly from spring, reaches a higher peak in mid-summer (July–August), and declines sharply after September. Surface energy partitioning exhibits a distinct seasonal shift: SHF exceeds LHF during the cold season (approximately November–March), whereas LHF dominates in the warm season (roughly May–September). This shift reflects a tendency toward evaporative cooling under moisture-favorable conditions and toward sensible heating under moisture-limited regimes.

Notably, high clouds make the dominant contribution to the total cloud cover over the TP and exhibit a clear seasonal phase (

Figure 4), implying that variations in high clouds may play a key role in the cloud–radiation–land surface energy exchange chain. Therefore, the subsequent sections focus on HCC and systematically quantify its co-variations with TPMI, snowfall, and surface radiative/heat fluxes as well as the underlying physical linkages.

3.3. Interannual Variation of Cloud Cover and Climate Variables

Building on the climatological spatial patterns and seasonal-cycle characteristics described above, this section examines the interannual variability and long-term linear trends of key climate variables over the TP during 2001–2023, with a particular focus on HCC and related hydroclimatic factors (TPMI, snowfall, the surface radiation budget, cloud radiative forcing, and heat fluxes).

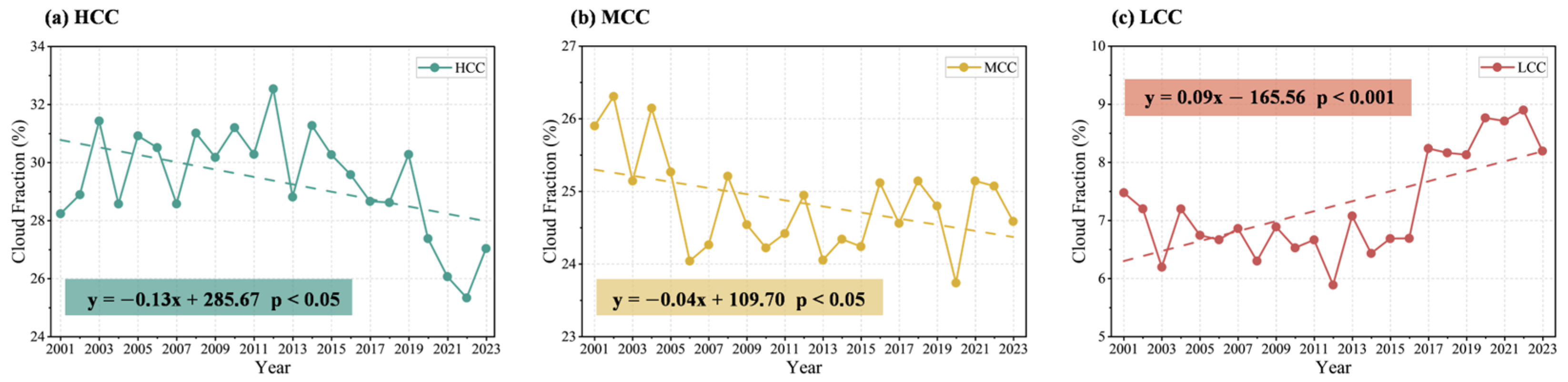

As shown in

Figure 8, all three cloud layers exhibit pronounced interannual variability superimposed on distinct long-term tendencies. HCC (

Figure 8a) shows a significant decreasing trend, with a slope of −1.3% decade

−1 (

p < 0.05) (

Table 1). Variability is relatively large in the early 2010s, whereas the decline becomes more pronounced after the mid-2010s, with notably lower values in recent years (especially since 2020). MCC (

Figure 8b) also exhibits a weak but significant downward trend (−0.4% decade

−1,

p < 0.05;

Table 1), with a smaller magnitude than that of HCC. In contrast, LCC (

Figure 8c) increases significantly, with a slope of +0.9% decade

−1 (

p < 0.05) (

Table 1), and it remains persistently elevated after ~2016, suggesting an enhanced contribution of low clouds in recent years. Overall, the TP cloud field during 2001–2023 undergoes a structural adjustment, characterized by a decrease in high- and mid-level clouds and an increase in low clouds. This long-term trend of reduced HCC incidence has been noted in recent studies [

47].

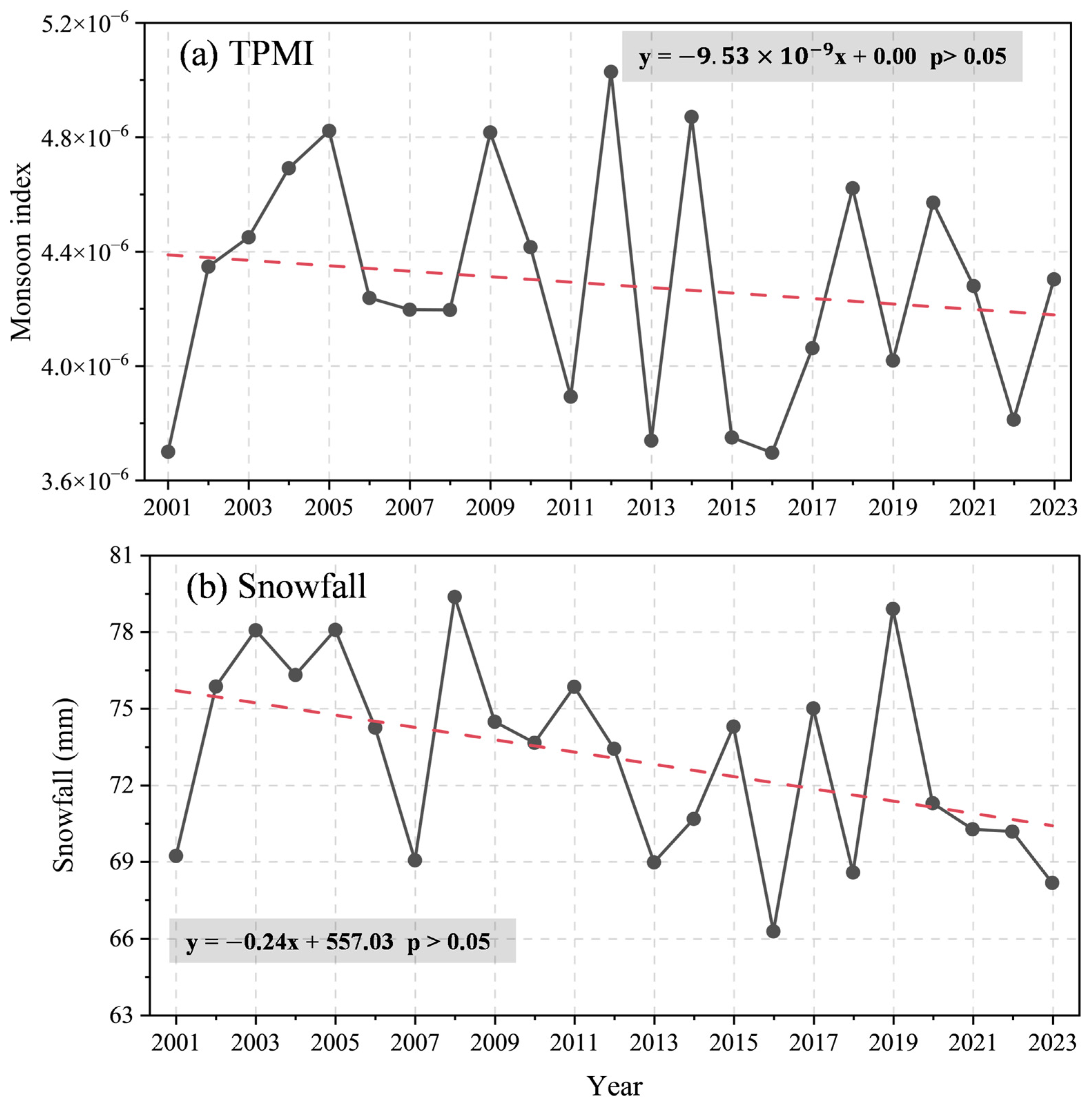

TPMI (

Figure 9a) displays substantial interannual fluctuations. Its linear trend is −9.53 × 10

−8 decade

−1 (

p > 0.05) (

Table 1), indicating a decreasing tendency that is not statistically significant over the study period. Snowfall (

Figure 9b) also shows substantial year-to-year variability, with a trend of −2.4 mm decade

−1 (

p > 0.05) (

Table 1), likewise negative but not significant. Overall, TPMI and snowfall are dominated by interannual variability, with trend signals that are weaker than those evident in the cloud variables.

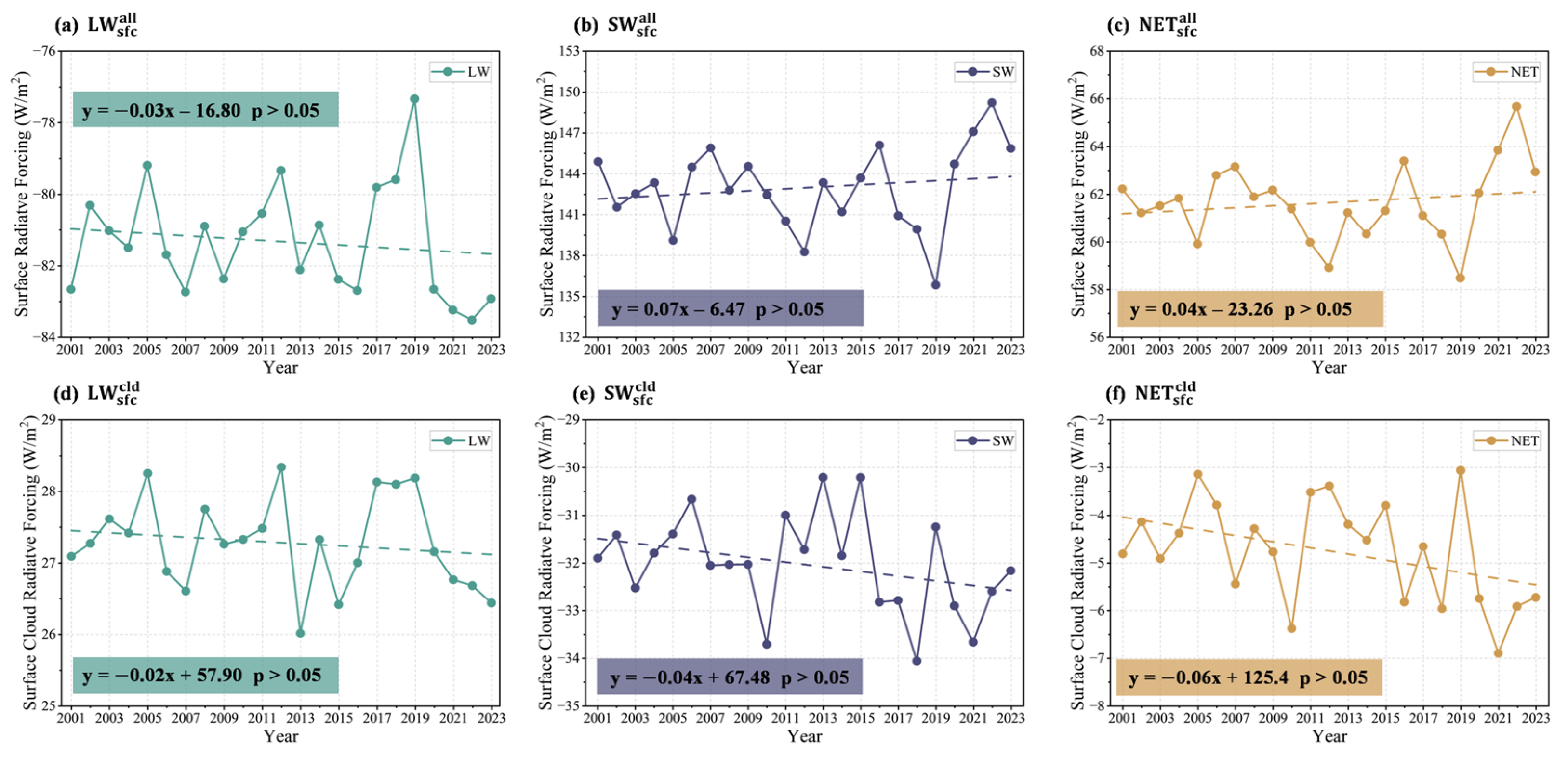

Figure 10 shows the interannual variability of the surface radiation budget and CRF. The all-sky surface net longwave radiation,

(

Figure 10a), is negative, with a trend of −0.3 W m

−2 decade

−1 (

p > 0.05) (

Table 1). The all-sky surface net shortwave radiation,

(

Figure 10b), is positive, with a trend of +0.7 W m

−2 decade

−1 (

p > 0.05), while the all-sky net radiation,

(

Figure 10c), is positive, with a trend of +0.4 W m

−2 decade

−1 (

p > 0.05). These results indicate that changes in the TP domain-mean surface net radiation are relatively small and statistically insignificant over 2001–2023, with interannual variability dominating the signal.

For CRF,

(

Figure 10d) is positive with a trend of −0.2 W m

−2 decade

−1 (

p > 0.05), and

(

Figure 10e) is negative with a trend of −0.4 W m

−2 decade

−1 (

p > 0.05). Consequently,

(

Figure 10f) is predominantly negative and trends toward more negative values, with a slope of −0.6 W m

−2 decade

−1 (

p > 0.05) (

Table 1). Although the CRF trends are not statistically significant, their directions suggest a slightly strengthened shortwave cooling (more negative

) and a corresponding shift of net CRF toward more negative values, which is physically consistent with the observed cloud-structure change—particularly the increase in low clouds, which are more effective at shortwave shading.

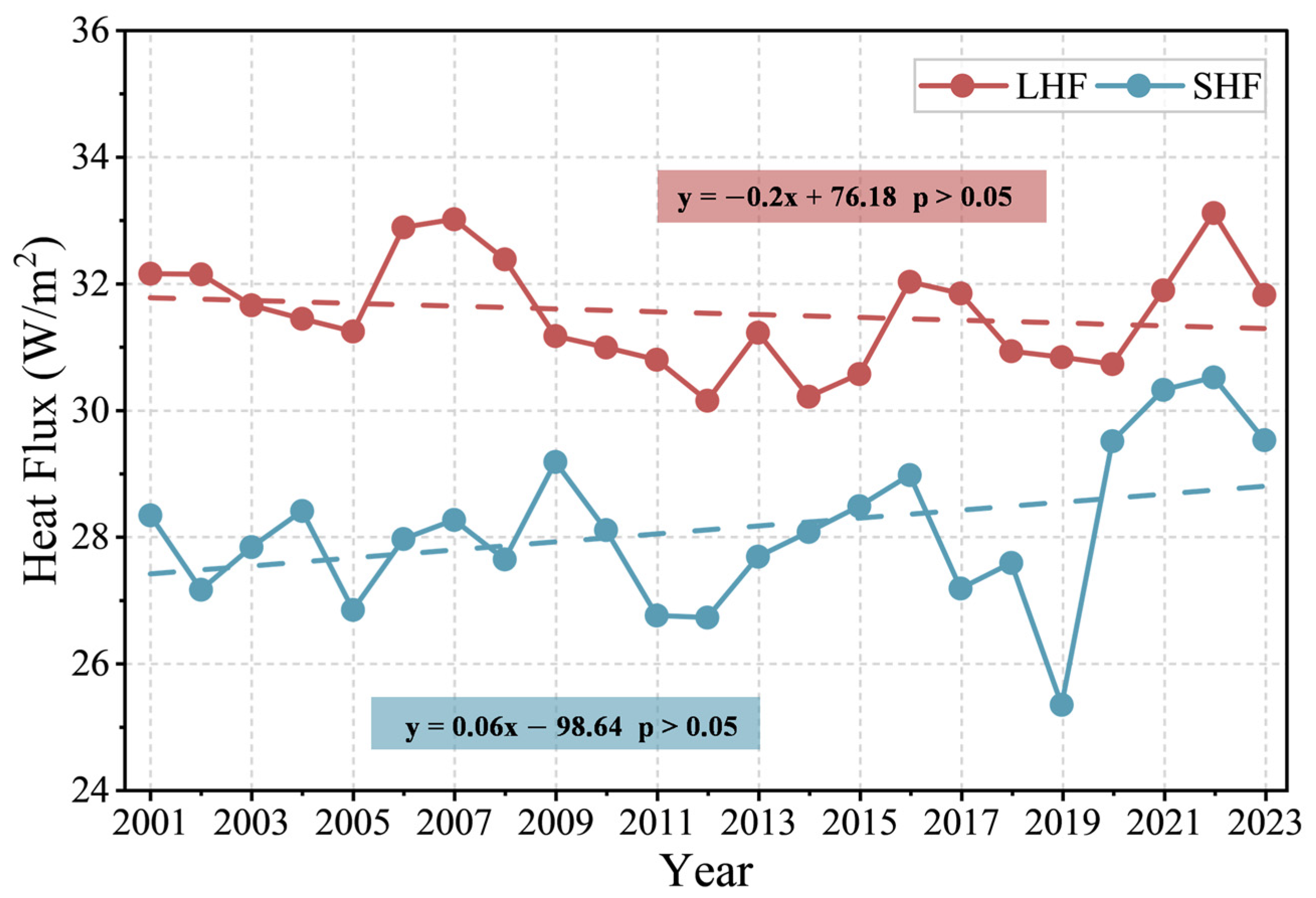

The heat fluxes (

Figure 11) are also mainly influenced by interannual variability. LHF shows a slight declining trend (−0.2 W m

−2 per decade,

p > 0.05), while SHF exhibits a slight increasing trend (+0.6 W m

−2 per decade,

p > 0.05) (

Table 1); neither trend reaches statistical significance. Regarding trend direction, the TP surface energy partitioning shows a weak tendency toward relatively stronger sensible heating and decreased evaporative fluxes (i.e., a slight “drying” signal).

3.4. Lead–Lag Analysis of HCC with Climate Variables

To further diagnose the phasing and potential directionality between HCC and key hydroclimatic and surface energy variables over the TP, we applied a lead–lag correlation analysis, which has been widely used in atmospheric science studies [

48,

49,

50]. Before calculating correlations, all the time series were converted to monthly anomalies by removing the climatological seasonal cycle and were further detrended so that the resulting correlations primarily reflect covariability on interannual timescales rather than shared seasonality or long-term trends. Lead–lag correlations were computed for lags within ±12 months, with statistical significance assessed at the

p < 0.05 level (red markers and the dashed critical line). Here, negative lags indicate that HCC leads the target variable, whereas positive lags indicate that HCC lags the target variable. Peak correlation coefficients and the associated lag months are summarized in

Table 2.

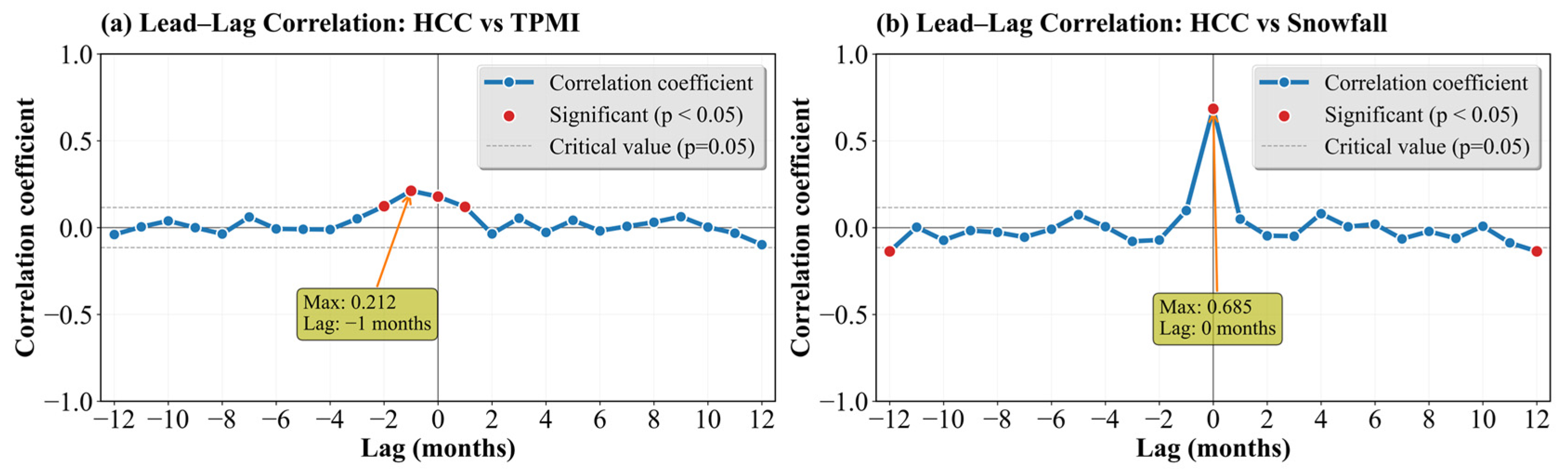

As shown in

Figure 12a, the correlation between HCC and TPMI is generally weak; however, a significant positive peak occurs when HCC leads TPMI by one month (r = 0.212,

p < 0.05;

Table 2). This suggests that anomalies in upper-level cloudiness tend to slightly precede changes in monsoon intensity, implying either a shared control by large-scale circulation/thermodynamic adjustments or that HCC may serve as a modest precursor signal for subsequent TPMI variability.

In contrast, HCC exhibits a much tighter relationship with snowfall (

Figure 12b). The correlation reaches a strong and significant maximum at zero lag (r = 0.685,

p < 0.05;

Table 2), indicating a largely synchronous coupling between enhanced high clouds and increased snowfall. This is consistent with the expectation that snowfall events over the TP are often associated with deep cloud systems and intensified upper-level cloud activity.

Figure 13 shows robust and physically consistent linkages between HCC and surface radiative variables, with most relationships peaking at zero lag, indicating near-instantaneous co-variability at monthly time scales.

HCC is significantly and positively correlated with all-sky net longwave radiation

at zero lag (r = 0.616,

p < 0.05;

Table 2), suggesting a concurrent adjustment in the surface longwave term under enhanced high-cloud conditions. Conversely, HCC is significantly and negatively correlated with all-sky net shortwave radiation

at zero lag (r = −0.559,

p < 0.05), reflecting the shortwave attenuation associated with increased cloudiness. As a result, HCC is significantly negatively correlated with all-sky net radiation

at zero lag (r = −0.419,

p < 0.05), indicating reduced net radiative energy available at the surface when high clouds are anomalously abundant.

HCC shows the strongest positive correlation with longwave CRF

at zero lag (r = 0.716,

p < 0.05;

Table 2), implying that increased high clouds are accompanied by a strengthened longwave warming effect attributable to clouds. Meanwhile, HCC is significantly negatively correlated with shortwave CRF

at zero lag (r = −0.306,

p < 0.05), consistent with enhanced cloud shortwave cooling (shading). Notably, the peak correlation for net CRF

occurs when HCC leads by one month (r = 0.281,

p < 0.05;

Table 2).

Compared with radiative variables, the relationships between HCC and heat fluxes are weaker but still show statistically significant peaks (

Figure 14). HCC is significantly and positively correlated with LHF at zero lag (r = 0.239,

p < 0.05;

Table 2), suggesting that enhanced high-cloud anomalies tend to coincide with increased evaporative fluxes. In contrast, the maximum correlation between HCC and sensible heat flux (SHF) occurs when HCC leads by one month (r = 0.395,

p < 0.05;

Table 2), implying a delayed adjustment of sensible heating in response to high-cloud variability, potentially mediated by changes in the surface energy budget and boundary-layer processes.

Overall,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 and

Table 2 indicate that (1) HCC is strongly synchronized with snowfall (r = 0.685), while its relationship with TPMI is weaker but significant with a ~1-month lead; (2) HCC shows the most robust and physically consistent associations with surface radiative variables, including enhanced longwave effects and reduced shortwave input, leading to reduced net radiation; and (3) heat fluxes exhibit more minor but significant correlations, with LHF largely synchronous and SHF tending to lag behind HCC by ~1 month. These phase relationships provide clear guidance for subsequent composite analysis, which contrasts circulation, hydrological, and surface energy responses under anomalously high- versus low-HCC conditions to elucidate the underlying physical pathways further.

3.5. Composite Analysis for High-HCC vs. Low-HCC Conditions

Figure 15 presents the event-centered composite evolution of key variables following winter low-HCC events (month 0, key January). As expected, HCC exhibits a pronounced negative anomaly around month 0 to +1, reaching its minimum near month +1 (

Figure 15a), confirming the robustness of the selected events. Snowfall (SF) shows a nearly synchronous decrease, also peaking in magnitude around month +1 (

Figure 15b), indicating a tight and immediate cloud–precipitation linkage during winter.

The responses of all-sky surface radiative fluxes display a broadly consistent sign tendency around the event time but are less temporally coherent (

Figure 15c). In particular,

and

tend to increase near month 0–+1, consistent with weakened cloud shading under reduced high clouds, whereas

shows comparatively smaller fluctuations. After the event, these all-sky signals oscillate around zero, implying that non-cloud influences (e.g., surface albedo and moisture variability) partially mask the cloud-related radiative response.

A clearer cloud-only signal emerges in the surface cloud radiative forcing (CRF) components (

Figure 15d). Net CRF (

) shows a detectable weakening within ~1–2 months after the HCC reduction (response onset), but the composite anomaly continues to evolve and reaches its strongest negative amplitude around month +5 to +6 (peak response), largely driven by the shortwave CRF component. This two-stage behavior helps reconcile differences with lead–lag correlation results: lead–lag identifies the lag of maximum linear phasing, whereas composites highlight the event response trajectory and its peak adjustment time.

Consistent with the radiative anomalies, the heat flux response is characterized by a stronger signal in SHF than in LHF (

Figure 15e). SHF shows a pronounced negative anomaly at a lag of about one month, followed by a gradual return to normal levels, whereas the LHF response is relatively weak and exhibits greater variability. The composite time series of the TPMI (

Figure 15f) displays noticeable month-to-month fluctuations, indicating that the monsoon index response is less stable at the event scale compared to the snowfall and radiative signals.

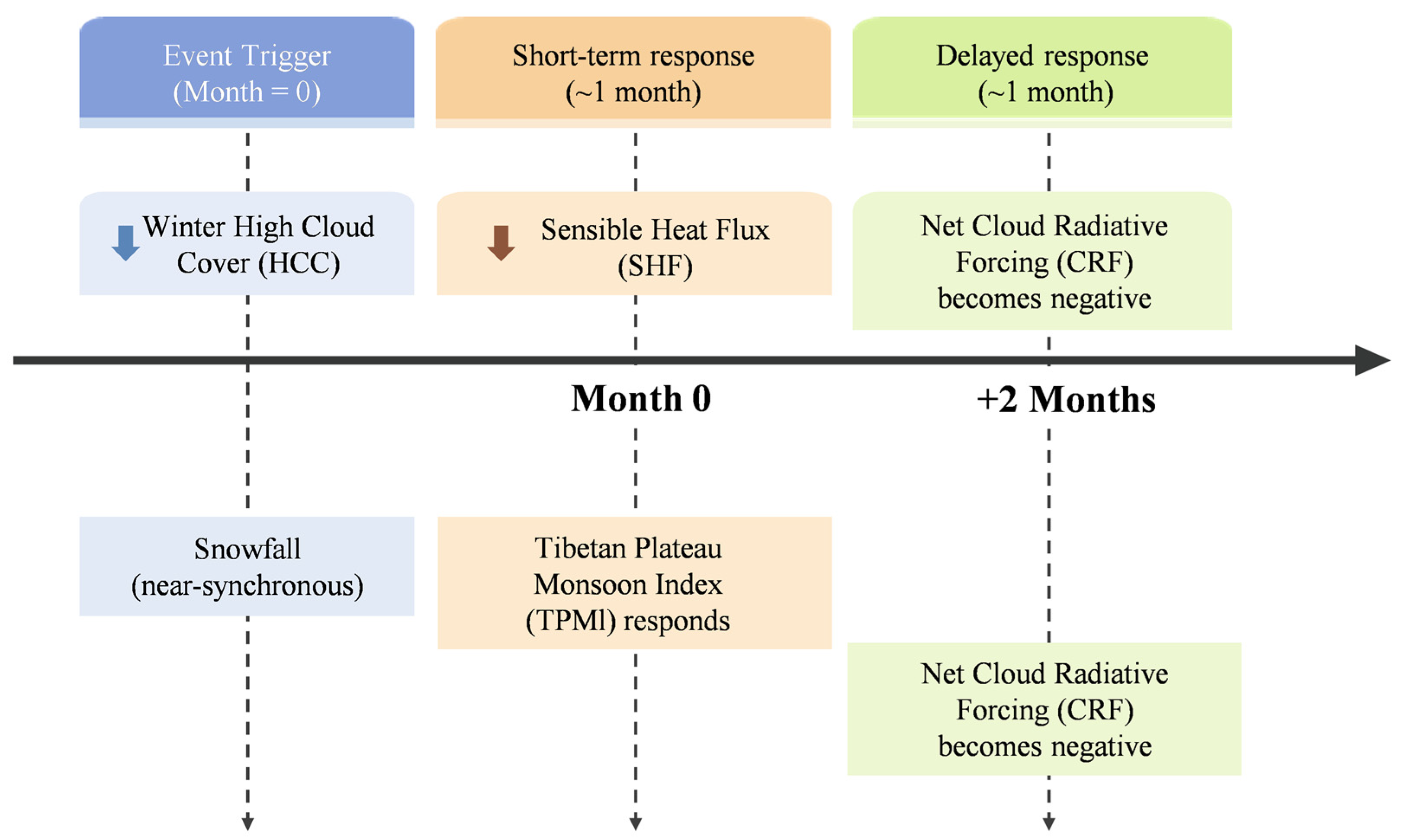

In summary, reduced HCC in winter suppresses snowfall, alters the surface radiation balance—manifested as enhanced shortwave radiation and weakened longwave radiation—reduces surface sensible heat flux, and may lead to a weakened plateau monsoon (

Table 3). It further confirms the lead–lag relationships identified in the preceding statistical analysis.

It is important to emphasize that the lead–lag correlation analysis and the event-based composite analysis serve complementary purposes. The former summarizes the average linear phase relationship across the entire record, while the latter isolates conditional responses during selected extreme winter low-HCC events. Therefore, differences in amplitude and apparent phasing can arise from seasonality, nonlinear couplings, and the conditional sampling of extremes.

3.6. Atmospheric Circulation Anomalies Associated with Extreme Cloud Years

To better illustrate the circulation–cloud–surface coupling suggested by the statistical analyses, we further compare two contrasting years characterized by extreme anomalies in cloud vertical structure. Specifically, 2012 exhibits the lowest LCC and the highest HCC, whereas 2022 shows the highest LCC and the lowest HCC.

In 2012, a persistent negative anomaly in the 500 hPa geopotential height (

Figure 16a) field indicated the dominance of an anomalous low-pressure system. This, combined with the strongest monsoon on record, triggered large-scale, deep ascent. This vigorous dynamic lifting effectively transported the limited available moisture to the upper troposphere, even amidst overall weak moisture transport, consequently resulting in the highest HCC. Conversely, the unstable atmospheric stratification and insufficient near-surface moisture (

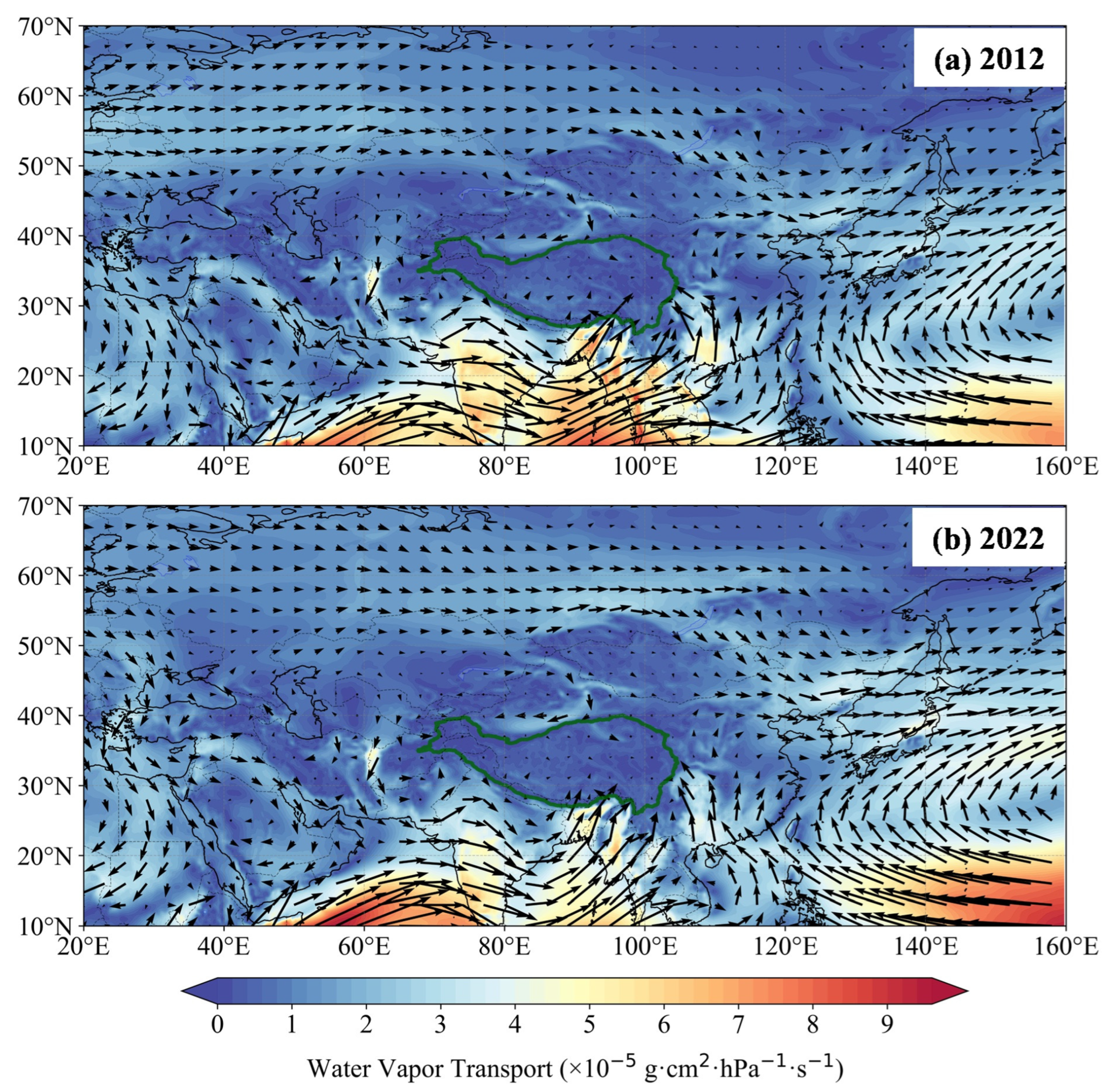

Figure 17a) suppressed the formation of low clouds, leading to the lowest LCC. The resultant cloud-free conditions enhanced incident solar radiation at the surface, which, together with negligible latent heat release due to weak cloud and precipitation processes, likely maximized sensible heat fluxes and minimized latent heat fluxes.

In contrast, the atmospheric configuration in 2022 was distinctive. A pronounced positive anomaly in the 500 hPa geopotential height field over the plateau (

Figure 16b) suppressed deep convection, resulting in the lowest high-cloud cover observed during the study period. Concurrently, anomalously strong moisture transport at 850 hPa (

Figure 17b) and its significant convergence over the plateau provided exceptionally abundant moisture conditions for the development of low clouds [

51,

52,

53]. Under the typically stable stratification at the base of this high-pressure system, the abundant moisture primarily formed extensive low clouds through shallow convection and boundary-layer processes, leading to their maximum coverage. The widespread formation of low clouds, together with localized convective activity triggered by the intense moisture convergence, released substantial condensational latent heat, thereby generating the strongest latent heat flux on record.

The SHF also peaked in this year, which was closely related to the aforementioned circulation and moisture configurations. On the one hand, the prevalence of clear or less cloudy skies under the high-pressure system enhanced surface shortwave radiation, causing a rapid daytime increase in surface temperature. On the other hand, although low-level moisture was abundant, the stable stratification inhibited the development of deep convection, limiting the release of available surface energy via large-scale ascending motions in the form of latent heat. Against the background of significantly increased net radiation, the rapid surface warming and potentially relatively limited soil moisture conditions collectively favored the partitioning of available energy toward sensible heat flux. This ultimately led to the strongest sensible heat flux through turbulent exchange.

To summarize, our findings highlight two dominant regimes governing the TP’s energy budget: one is driven by anomalous low pressure and strong ascending motion, characterized by the most extensive high-level cloud cover and dominant sensible heating; the other is sustained by stable high pressure and abundant low-level moisture, which favors the formation of widespread low clouds accompanied by significant latent heat release. These regimes demonstrate that atmospheric circulation dictates the vertical cloud structure by modulating ascent strength and moisture availability. Consequently, the resulting cloud distribution directly modulates the surface radiation budget and partitions turbulent energy fluxes, thereby imposing a primary control on the plateau’s surface energy balance [

54,

55].

4. Discussion

This study systematically analyzes the evolution of cloud vertical structure over the TP and its interaction with the surface energy budget, revealing a process framework of multi-scale coupling that is more complex than the traditional “heat-pump” linkage. Our results demonstrate that the vertical distribution of clouds over the TP is not solely driven by thermodynamic processes but is strongly modulated by large-scale circulation regimes and moisture transport pathways. Specifically, the observed trend of decreasing HCC and increasing LCC during 2001–2023 is consistent with long-term changes in mid-tropospheric geopotential height and the corresponding adjustment in dynamic stability, confirming the control of dynamic forcing and stratification on cloud vertical structure.

A key finding is the marked temporal lags and asynchronous coupling between cloud variables and surface processes. HCC and snowfall are highly synchronized at monthly scales, highlighting the importance of deep convective cloud systems for cold-season precipitation over the TP. In contrast, the net CRF and SHF respond to HCC anomalies with a lag of about 1–2 months, suggesting that the radiative modulation exerted by clouds and its ultimate thermal impact require time to fully materialize through surface–boundary-layer interactions. Especially in winter, reduced HCC suppresses snowfall and weakens the longwave cloud greenhouse effect, leading to a shift toward negative net CRF anomalies and decreased SHF after about 1–2 months. This clear lagged sequence elucidates a key pathway through which winter cloud anomalies influence surface thermal forcing.

Notably, winter low-HCC events are also associated with a concurrent response in the TPMI, indicating that winter cloud–radiation–surface energy perturbations can project onto large-scale circulation as represented by the monsoon index. However, the full-record lead–lag correlations are relatively weak, implying that cloud–circulation coupling may be season- or regime-dependent, with winter events providing a clearer signal (

Figure 18).

This study underscores the importance of accurately representing TP cloud vertical structure and its associated couplings in climate models. Future modeling efforts should focus on capturing: (1) the radiative signature of HCC anomalies and their lagged effects; (2) the strong linkage between HCC and winter snowfall; and (3) the conditional pathway through which reduced winter clouds weaken CRF and SHF and subsequently affect circulation indices. Current limitations mainly stem from uncertainties in reanalysis-based surface fluxes and the smoothing of sub-monthly processes by monthly-mean data. Follow-up studies employing high-resolution process-resolving simulations, combined with observational constraints on near-surface stability and boundary-layer structure, could further clarify causal relationships and seasonal dependencies. Ultimately, integrating these observed relationships into a conceptual or reduced-order dynamical framework would help systematically understand the interactions between plateau heating, cloud vertical structure, and monsoon variability and better quantify the associated feedback mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

Using CERES satellite observations from 2001 to 2023, we applied an improved cloud classification algorithm to construct a long-term cloud-type dataset for the TP. Combined with ERA5 reanalysis data, we systematically analyzed the long-term trends and lead–lag relationships among multiple climatic variables, including cloud types, surface radiation, cloud radiative forcing, sensible and latent heat fluxes, snowfall, and the plateau monsoon index. Furthermore, we employed composite analysis to validate the robustness of the identified statistical relationships. The main conclusions are the following:

(1) TP cloud vertical structure has undergone a measurable adjustment during 2001–2023, with decreasing high- and mid-level cloud cover and increasing low cloud cover, indicating a shift in the relative prevalence of deep versus boundary-layer cloud regimes;

(2) HCC is tightly coupled to TP snowfall and surface radiative variability at monthly time scales. HCC and snowfall exhibit a strong synchronous relationship, consistent with snowfall being associated with deep cloud systems. HCC also shows robust concurrent relationships with all-sky surface radiative components, increasing the longwave term while reducing shortwave input and net surface radiation, with a small (~1 month) lead signal in net CRF;

(3) Heat flux responses are weaker but physically coherent. HCC tends to lead SHF by about one month, while LHF varies more synchronously, suggesting that a short-delayed adjustment follows high-cloud anomalies in surface sensible heating;

(4) Winter low-HCC events reveal a consistent pathway: reduced high cloud occurrence is accompanied by suppressed snowfall, a delayed weakening of net cloud radiative forcing (1–2 months), reduced SHF, and a significant TPMI response near month 0, implying that winter cloud–radiation–surface energy perturbations can project onto plateau-scale circulation variability;

(5) Circulation-regime contrasts support the statistical relationships. A dynamically lifted regime (e.g., 2012) favors enhanced high clouds under anomalous ascent. In contrast, a more stable, moisture-convergent regime (e.g., 2022) favors increased low cloud cover, illustrating how large-scale dynamics and moisture pathways regulate TP cloud vertical structure.

Overall, the results highlight that TP cloud feedbacks influence thermal forcing primarily through radiative modulation and cloud–snowfall coupling, with seasonally dependent pathways that can link winter cloud anomalies to subsequent surface energy and circulation responses. Improving the representation of cloud vertical structure and cloud–radiation–precipitation processes over the TP should therefore be a priority for reducing model biases in TP surface forcing and associated monsoon variability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B.; methodology, F.B.; software, F.B.; validation, F.B.; formal analysis, F.B.; investigation, F.B.; resources, F.B.; data curation, F.B.; writing—original draft preparation, F.B.; writing—review and editing, F.B., H.L. and R.X.; visualization, F.B.; supervision, F.B. and H.L.; project administration, F.B. and H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 42025504 and 42430604.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TP | Tibetan Plateau |

| CERES | Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| TPMI | Tibetan Plateau Monsoon Index |

| Q | Horizontal moisture flux vector |

| V | Wind Vector |

| q | Specific Humidity |

| HCC | High Cloud Cover |

| MCC | Mid-level Cloud Cover |

| LCC | Low Cloud Cover |

| CRF | Cloud Radiative Forcing |

| Surface longwave radiation (all-sky) |

| Surface shortwave radiation (all-sky) |

| Surface net radiation (all-sky) |

| Surface cloud longwave radiative forcing |

| Surface cloud shortwave radiative forcing |

| Surface cloud net radiative forcing |

| LHF | Latent Heat Flux |

| SHF | Sensible Heat Flux |

| SF | Snowfall |

References

- Zhong, L.; Ma, Y.; Salama, M.S.; Su, Z. Assessment of vegetation dynamics and their response to variations in precipitation and temperature in the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Change 2010, 103, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, B. Climatic warming in the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades. Int. J. Climatol. A J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2000, 20, 1729–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, A.; Wu, G. Role of the Tibetan Plateau thermal forcing in the summer climate patterns over subtropical Asia. Clim. Dyn. 2005, 24, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, M.; Wu, G.-X. Effects of the Tibetan plateau. In The Asian Monsoon; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 513–549. [Google Scholar]

- Yanai, M.; Li, C.; Song, Z. Seasonal heating of the Tibetan Plateau and its effects on the evolution of the Asian summer monsoon. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 1992, 70, 319–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, M.; Yang, H.; Duan, A.; He, B.; Yang, S.; Wu, G. Land–atmosphere–ocean coupling associated with the Tibetan Plateau and its climate impacts. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 534–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flohn, H. Large-scale aspects of the “summer monsoon” in South and East Asia. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 1957, 35, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T. The wind structure and heat balance in the lower troposphere over Tibetan Plateau and its surroundings. Acta Meteor. Sin. 1957, 28, 108–121. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, A.; Wang, T.; Wan, R.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Liang, X. The influence of mechanical and thermal forcing by the Tibetan Plateau on Asian climate. J. Hydrometeorol. 2007, 8, 770–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, P.; Boos, W.R.; Battisti, D.S. Orographic controls on climate and paleoclimate of Asia: Thermal and mechanical roles for the Tibetan Plateau. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2010, 38, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.-Z.; Wu, G.-X. The role of the heat source of the Tibetan Plateau in the general circulation. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 1998, 67, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yao, T.; Zhong, L.; Wang, B.; Xu, X.; Hu, Z.; Ma, W.; Sun, F.; Han, C.; Li, M. Comprehensive study of energy and water exchange over the Tibetan Plateau: A review and perspective: From GAME/Tibet and CAMP/Tibet to TORP, TPEORP, and TPEITORP. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 237, 104312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhao, P.; Chen, J. Possible effect of the thermal condition of the Tibetan Plateau on the interannual variability of the summer Asian–Pacific oscillation. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 9965–9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hu, Z.; Xie, Z.; Ma, W.; Wang, B.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Zhong, L.; Sun, F.; Gu, L. A long-term (2005–2016) dataset of hourly integrated land–atmosphere interaction observations on the Tibetan Plateau. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 2937–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Trenberth, K.E. Orographically forced planetary waves in the Northern Hemisphere winter: Steady state model with wave-coupled lower boundary formulation. J. Atmos. Sci. 1988, 45, 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskins, B.J.; Karoly, D.J. The steady linear response of a spherical atmosphere to thermal and orographic forcing. J. Atmos. Sci. 1981, 38, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Zhang, Y. Tibetan Plateau forcing and the timing of the monsoon onset over South Asia and the South China Sea. Mon. Weather Rev. 1998, 126, 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.H.; Liu, X. Relationship between the Tibetan Plateau heating and East Asian summer monsoon rainfall. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charney, J.G.; Eliassen, A. A numerical method for predicting the perturbations of the middle latitude westerlies. Tellus 1949, 1, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.H.; Seo, K.H.; Wang, B. Dynamical control of the Tibetan Plateau on the East Asian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2019, 46, 7672–7679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, B. On the influence of the earth’s orography on the general character of the westerlies. Tellus 1950, 2, 184–195. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Sheng, C.; Wu, G.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y. Quantification of seasonal and interannual variations of the Tibetan Plateau surface thermodynamic forcing based on the potential vorticity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL097222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J. Cloud vertical structure, precipitation, and cloud radiative effects over Tibetan Plateau and its neighboring regions. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2016, 121, 5864–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhao, A. Cloud properties and dynamics over the Tibetan Plateau–A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2024, 248, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, K.; Yu, Y.; Lu, H.; Lin, Y. Land–atmosphere interactions partially offset the accelerated Tibetan Plateau water cycle through dynamical processes. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 3867–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, K.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yang, B.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y. Reducing winter precipitation biases over the western Tibetan Plateau in the Model for Prediction Across Scales (MPAS) with a revised parameterization of orographic gravity wave drag. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD039123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wu, H.; Qin, J.; Lin, C.; Tang, W.; Chen, Y. Recent climate changes over the Tibetan Plateau and their impacts on energy and water cycle: A review. Glob. Planet. Change 2014, 112, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Letu, H.; Shang, H.; Ri, X.; Chen, D.; Yao, T.; Wei, L.; Tang, C.; Yin, S.; Ji, D. Advancing cloud classification over the Tibetan Plateau: A new algorithm reveals seasonal and diurnal variations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL109590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letu, H.; Nakajima, T.Y.; Wang, T.; Shang, H.; Ma, R.; Yang, K.; Baran, A.J.; Riedi, J.; Ishimoto, H.; Yoshida, M. A new benchmark for surface radiation products over the East Asia–Pacific region retrieved from the Himawari-8/AHI next-generation geostationary satellite. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, E873–E888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Shi, J.; Wang, T.; Letu, H.; Yuan, P.; Zhou, W.; Hu, L. Evaluation of the Himawari-8 shortwave downward radiation (SWDR) product and its comparison with the CERES-SYN, MERRA-2, and ERA-interim datasets. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 12, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fan, G.-z.; Hua, W.; Wang, B.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, D. Distribution characteristics of plateau monsoon and a contrastive analysis of plateau monsoon index. Plateau Meteorol. 2015, 34, 1517–1530. [Google Scholar]

- National Basic Geographic Information Center. Administrative Boundaries Data at 1:1000 000 Scale Over the Tibetan Plateau (2017); National Basic Geographic Information Center: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neiman, P.J.; Ralph, F.M.; Wick, G.A.; Lundquist, J.D.; Dettinger, M.D. Meteorological characteristics and overland precipitation impacts of atmospheric rivers affecting the West Coast of North America based on eight years of SSM/I satellite observations. J. Hydrometeorol. 2008, 9, 22–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixóto, J.P.; Oort, A.H. Physics of climate. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1984, 56, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Yan, X.; Tsai, C.L. Linear regression. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2012, 4, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulud, D.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A review on linear regression comprehensive in machine learning. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. Trends 2020, 1, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanık, G.K.; Güler, N. A study on multiple linear regression analysis. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 106, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Standard deviations and standard errors. BMJ 2005, 331, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Ji, H.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Lu, F.J.T.; Climatology, A. Lead-lag correlations between snow cover and meteorological factors at multi-time scales in the Tibetan Plateau under climate warming. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2021, 146, 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, P.; Wu, Z. Contribution of the Tibetan Plateau winter snow cover to seasonal prediction of the East Asian summer monsoon. Atmos.-Ocean 2023, 61, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guo, W.; Qiu, B.; Xue, Y.; Hsu, P.-C.; Wei, J. Influence of Tibetan Plateau snow cover on East Asian atmospheric circulation at medium-range time scales. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-H.; Huang, Y.-C.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Terng, C.-T.; Chen, J.; Jan, J.C. Revisiting regression methods for estimating long-term trends in sea surface temperature. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 24, 2481–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Duan, A.; Liu, Y.; Mao, J.; Ren, R.; Bao, Q.; He, B.; Liu, B.; Hu, W. Tibetan Plateau climate dynamics: Recent research progress and outlook. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2015, 2, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bony, S.; Stevens, B.; Frierson, D.M.; Jakob, C.; Kageyama, M.; Pincus, R.; Shepherd, T.G.; Sherwood, S.C.; Siebesma, A.P.; Sobel, A.H. Clouds, circulation and climate sensitivity. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Liang, S. Surface-sensible and latent heat fluxes over the Tibetan Plateau from ground measurements, reanalysis, and satellite data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 5659–5677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Gao, J. The influence of cloud cover on elevation-dependent warming over the Tibetan Plateau from 1984 to 2022. Atmos. Res. 2025, 323, 108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Huang, A.; Gu, W.; Ma, Y. Soil Temperature Controls the Month-To-Month Lead-Lag Correlations of Near-Surface Air Temperatures in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yangtze River Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD039036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchida, K.; Mochizuki, T.; Kawamura, R.; Kawano, T.; Kamae, Y. Diversity of lagged relationships in global means of surface temperatures and radiative budgets for CMIP6 piControl simulations. J. Clim. 2023, 36, 8743–8759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, M.A.; Clement, A.C.; Murphy, L.N.; Bellomo, K. Low-pass filtering, heat flux, and Atlantic multidecadal variability. J. Clim. 2017, 30, 7529–7553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, T.W.; Lebo, Z.J. Linking large-scale circulation patterns to low-cloud properties. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 7125–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, A.; Albern, N.; Ceppi, P.; Grise, K.; Li, Y.; Medeiros, B. Clouds, radiation, and atmospheric circulation in the present-day climate and under climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2021, 12, e694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Feingold, G. On the relationship between open cellular convective cloud patterns and the spatial distribution of precipitation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.C.; Barnett, T.P.; Roeckner, E.; Vonder Haar, T.H. An analysis of the relationship between cloud anomalies and sea surface temperature anomalies in a global circulation model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1992, 97, 20497–20506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Groisman, P.Y.; Bradley, R.S.; Keimig, F.T. Temporal changes in the observed relationship between cloud cover and surface air temperature. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 4341–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of the multi-year (2001–2023) mean high (HCC), mid-level (MCC), and low cloud cover (LCC) over the TP: (a) HCC, (b) MCC, and (c) LCC.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of the multi-year (2001–2023) mean high (HCC), mid-level (MCC), and low cloud cover (LCC) over the TP: (a) HCC, (b) MCC, and (c) LCC.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of the multi-year (2001–2023) mean surface radiation budget over the TP: (a) all-sky net longwave radiation, (b) all-sky net shortwave radiation, and (c) all-sky net radiation; and the cloud radiative forcing: (d) longwave, (e) shortwave, and (f) net.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of the multi-year (2001–2023) mean surface radiation budget over the TP: (a) all-sky net longwave radiation, (b) all-sky net shortwave radiation, and (c) all-sky net radiation; and the cloud radiative forcing: (d) longwave, (e) shortwave, and (f) net.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of the multi-year (2001–2023) mean surface heat fluxes over the TP: (a) latent heat flux (LHF) and (b) sensible heat flux (SHF).

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of the multi-year (2001–2023) mean surface heat fluxes over the TP: (a) latent heat flux (LHF) and (b) sensible heat flux (SHF).

Figure 4.

Seasonal cycle of (a) total cloud cover (TCC) and (b) the contribution of HCC, MCC, and LCC to TCC over the TP.

Figure 4.

Seasonal cycle of (a) total cloud cover (TCC) and (b) the contribution of HCC, MCC, and LCC to TCC over the TP.

Figure 5.

Seasonal cycle of (a) Tibetan Plateau Monsoon Intensity (TPMI) and (b) snowfall over the TP.

Figure 5.

Seasonal cycle of (a) Tibetan Plateau Monsoon Intensity (TPMI) and (b) snowfall over the TP.

Figure 6.

Seasonal cycle of the (a) surface radiation budget and (b) surface cloud radiative forcing over the TP.

Figure 6.

Seasonal cycle of the (a) surface radiation budget and (b) surface cloud radiative forcing over the TP.

Figure 7.

Seasonal cycle of Latent Heat Flux (LHF) and Sensible Heat Flux (SHF) over the TP.

Figure 7.

Seasonal cycle of Latent Heat Flux (LHF) and Sensible Heat Flux (SHF) over the TP.

Figure 8.

Interannual variation of (a) HCC, (b) MCC, and (c) LCC over the TP during 2001–2023.

Figure 8.

Interannual variation of (a) HCC, (b) MCC, and (c) LCC over the TP during 2001–2023.

Figure 9.

Interannual variation of (a) TPMI and (b) snowfall over the TP during 2001–2023. The red dashed line denotes the linear trend.

Figure 9.

Interannual variation of (a) TPMI and (b) snowfall over the TP during 2001–2023. The red dashed line denotes the linear trend.

Figure 10.

Interannual variations (2001–2023) over the TP: (a) net longwave radiation, (b) net shortwave radiation, and (c) net radiation; and the cloud radiative forcing: (d) longwave, (e) shortwave, and (f) net.

Figure 10.

Interannual variations (2001–2023) over the TP: (a) net longwave radiation, (b) net shortwave radiation, and (c) net radiation; and the cloud radiative forcing: (d) longwave, (e) shortwave, and (f) net.

Figure 11.

Interannual variation of LHF and SHF over the TP during 2001–2023.

Figure 11.

Interannual variation of LHF and SHF over the TP during 2001–2023.

Figure 12.

Lead–lag correlation between the HCC and (a) TPMI and (b) Snowfall.

Figure 12.

Lead–lag correlation between the HCC and (a) TPMI and (b) Snowfall.

Figure 13.

Lead–lag correlation of HCC with (a) all-sky net longwave radiation (), (b) all-sky net shortwave radiation (), (c) all-sky net radiation (), (d) longwave cloud radiative forcing (), (e) shortwave cloud radiative forcing (), and (f) net cloud radiative forcing ().

Figure 13.

Lead–lag correlation of HCC with (a) all-sky net longwave radiation (), (b) all-sky net shortwave radiation (), (c) all-sky net radiation (), (d) longwave cloud radiative forcing (), (e) shortwave cloud radiative forcing (), and (f) net cloud radiative forcing ().

Figure 14.

Lead–lag correlation between the HCC and (a) LHF and (b) SHF.

Figure 14.

Lead–lag correlation between the HCC and (a) LHF and (b) SHF.

Figure 15.

Composite evolution of key climatic variables following winter HCC reduction over the TP: (a) HCC, (b) snowfall (SF), (c) all-sky surface radiative fluxes (RF), (d) surface cloud radiative forcing (CRF), (e) sensible and latent heat fluxes (HF), and (f) the Tibetan Plateau Monsoon Index (TPMI).

Figure 15.

Composite evolution of key climatic variables following winter HCC reduction over the TP: (a) HCC, (b) snowfall (SF), (c) all-sky surface radiative fluxes (RF), (d) surface cloud radiative forcing (CRF), (e) sensible and latent heat fluxes (HF), and (f) the Tibetan Plateau Monsoon Index (TPMI).

Figure 16.

Comparison of the 500 hPa geopotential height over the TP and surrounding regions during the summer monsoon season for (a) 2012 and (b) 2022. The green line delineates the boundary of the TP.

Figure 16.

Comparison of the 500 hPa geopotential height over the TP and surrounding regions during the summer monsoon season for (a) 2012 and (b) 2022. The green line delineates the boundary of the TP.

Figure 17.

Comparison of 850 hPa moisture transport over the TP and surrounding regions during the summer monsoon season for (a) 2012 and (b) 2022. The green line delineates the boundary of the TP.

Figure 17.

Comparison of 850 hPa moisture transport over the TP and surrounding regions during the summer monsoon season for (a) 2012 and (b) 2022. The green line delineates the boundary of the TP.

Figure 18.

Schematic illustration of cross-seasonal responses to reduced winter HCC over the TP.

Figure 18.

Schematic illustration of cross-seasonal responses to reduced winter HCC over the TP.

Table 1.

Linear trends of major climatic variables over the TP (2001–2023).

Table 1.

Linear trends of major climatic variables over the TP (2001–2023).

| Variable | Slope (Decade) | p-Value |

|---|

| HCC | −1.3% decade−1 | <0.05 |

| MCC | −0.4% decade−1 | <0.05 |

| LCC | +0.9% decade−1 | <0.05 |

| TPMI | −9.53 × 10−9 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| Snowfall | −2.4 mm decade−1 | >0.05 |

| −0.3 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| +0.7 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| +0.4 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| −0.2 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| −0.4 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| −0.6 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| LHF | −0.2 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

| SHF | +0.6 W m−2 decade−1 | >0.05 |

Table 2.

Peak Lead–Lag Correlation Coefficients Between HCC and Climate Variables.

Table 2.

Peak Lead–Lag Correlation Coefficients Between HCC and Climate Variables.

Cloud

Type | Variables | Lag (Months) | Correlation Coefficient (r) | p-Value | Temporal

Relationship |

|---|

| HCC | TPMI | −1 | +0.212 | <0.05 | Leads TPMI |

| HCC | Snowfall | 0 | +0.685 | <0.05 | Synchronous |

| HCC | | 0 | +0.616 | <0.05 | Synchronous |

| HCC | | 0 | −0.559 | <0.05 | Synchronous |

| HCC | | 0 | −0.419 | <0.05 | Synchronous |

| HCC | | 0 | +0.716 | <0.05 | Synchronous |

| HCC | | 0 | −0.306 | <0.05 | Synchronous |

| HCC | | −1 | +0.281 | <0.05 | |

| HCC | LHF | 0 | +0.239 | <0.05 | Synchronous |

| HCC | SHF | −1 | +0.395 | <0.05 | Leads SHF |

Table 3.

Key physical relationships between winter HCC anomalies and other variables based on composite analysis.

Table 3.

Key physical relationships between winter HCC anomalies and other variables based on composite analysis.

| p-Value |

|---|

| HCC → Snowfall | p < 0.001 |

| p < 0.001 |

| p < 0.001 |

| HCC → SHF | p = 0.005 |

| HCC → TPMI | p = 0.001 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |