Deep Transfer Learning for UAV-Based Cross-Crop Yield Prediction in Root Crops

Highlights

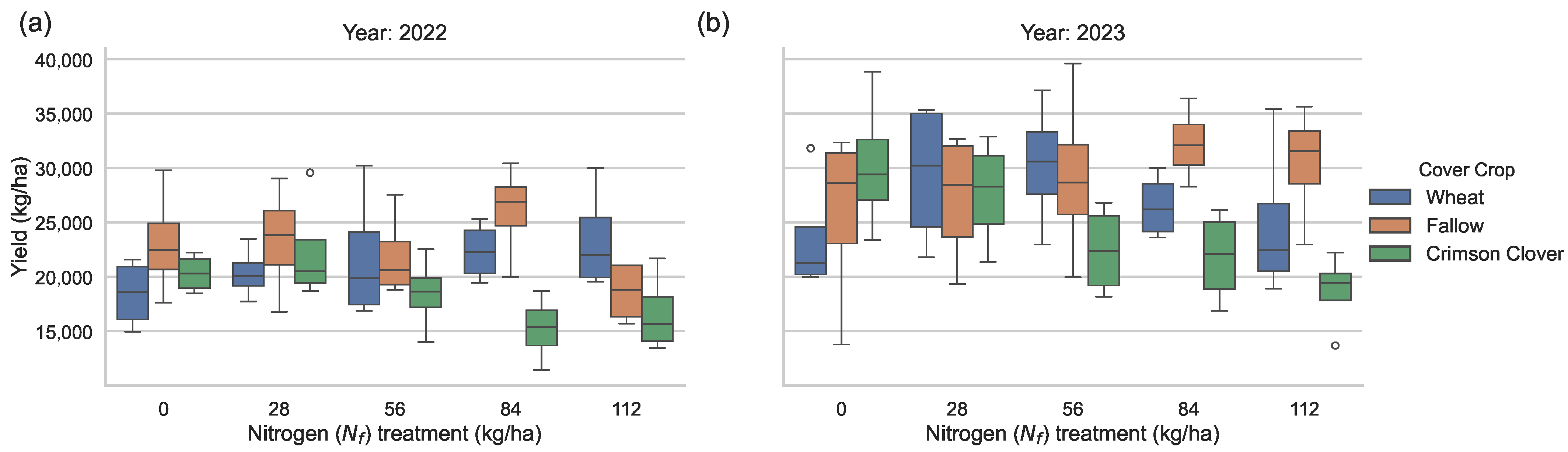

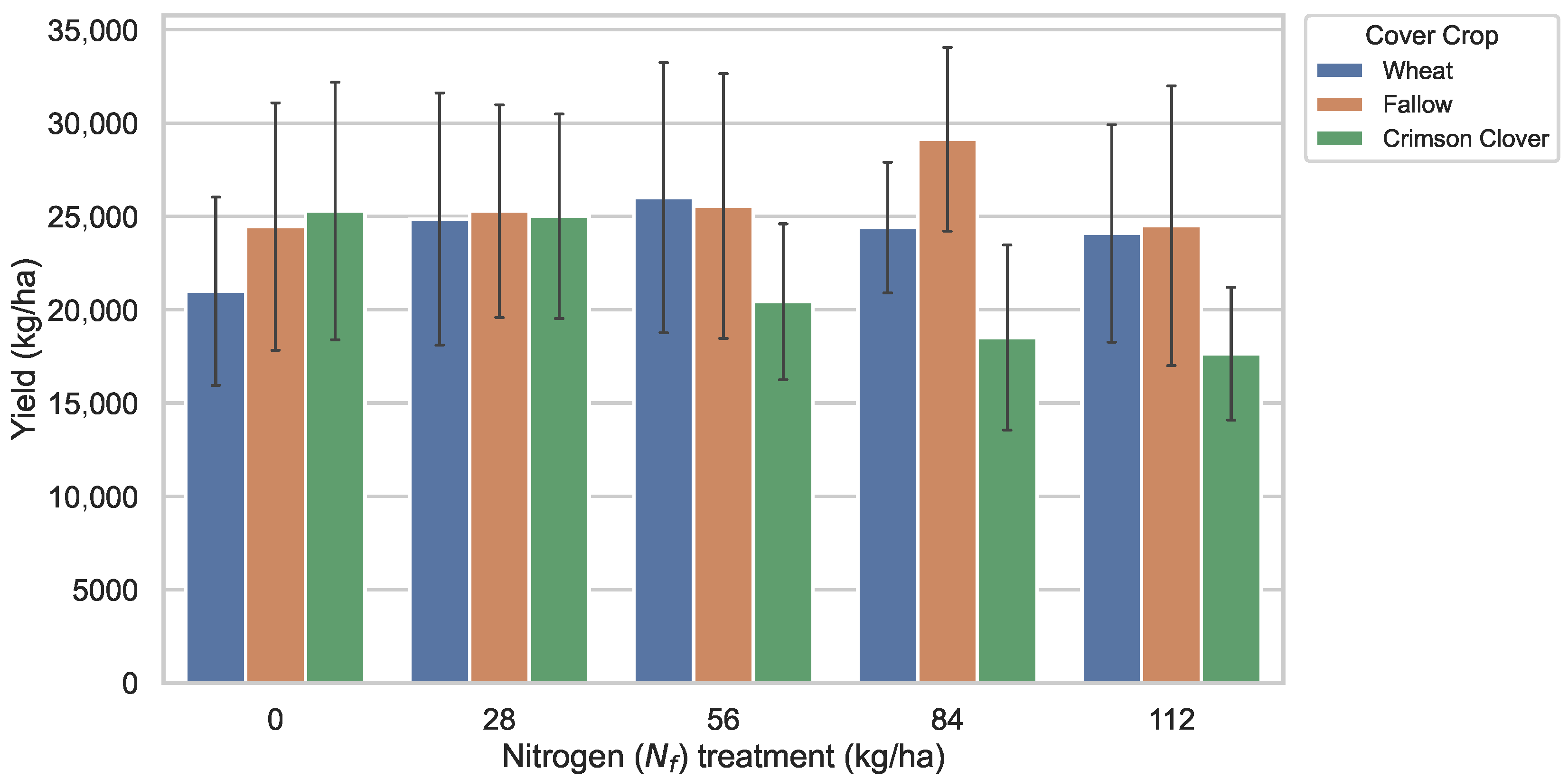

- Two-way ANOVA revealed significant effects of cover crop on sweet potato yield, whereas nitrogen rate and the interaction term were not substantial.

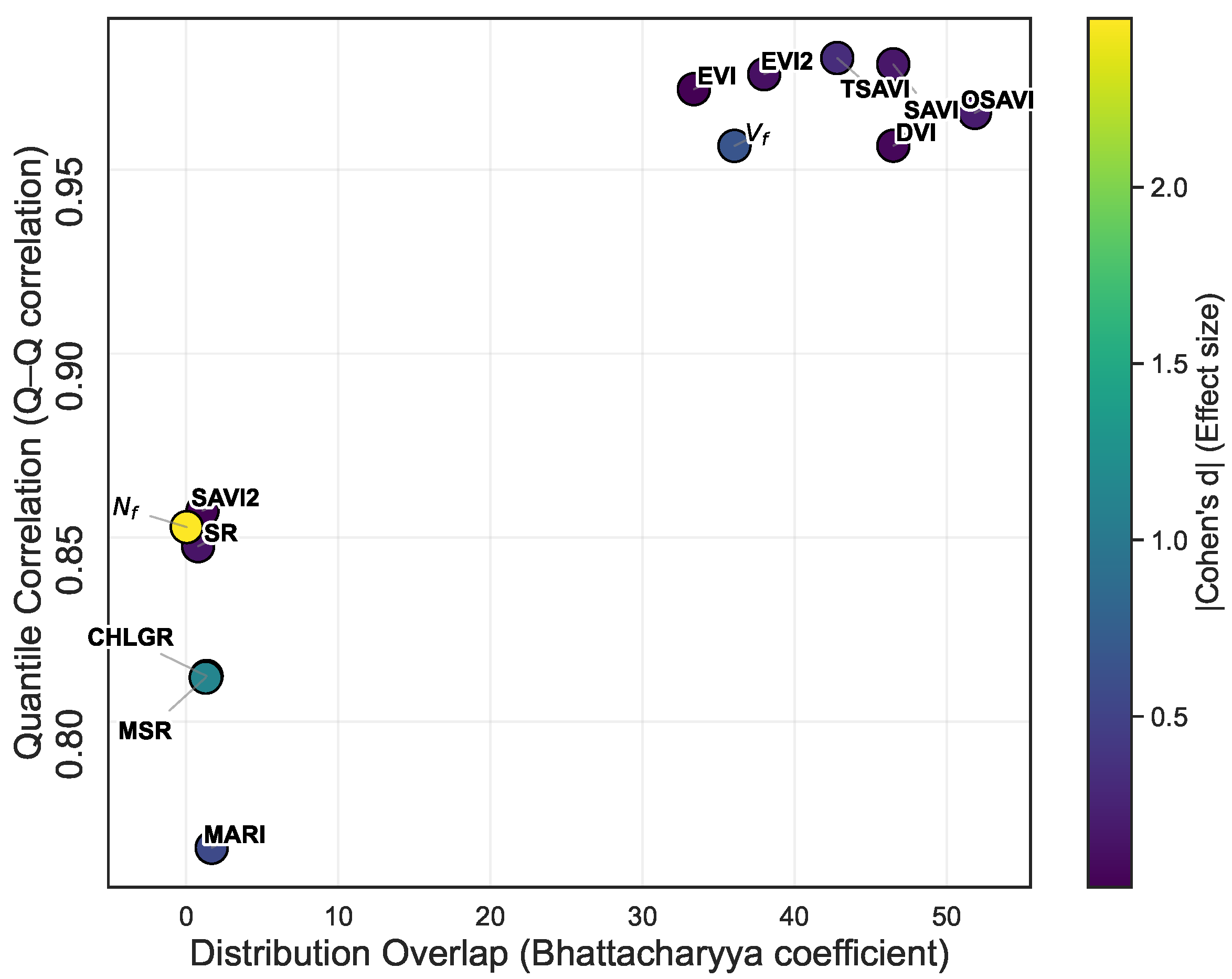

- Cross-crop robustness analysis identified SAVI, OSAVI, EVI, EVI2, DVI, TSAVI, and as the most transferable features between potato and sweet potato.

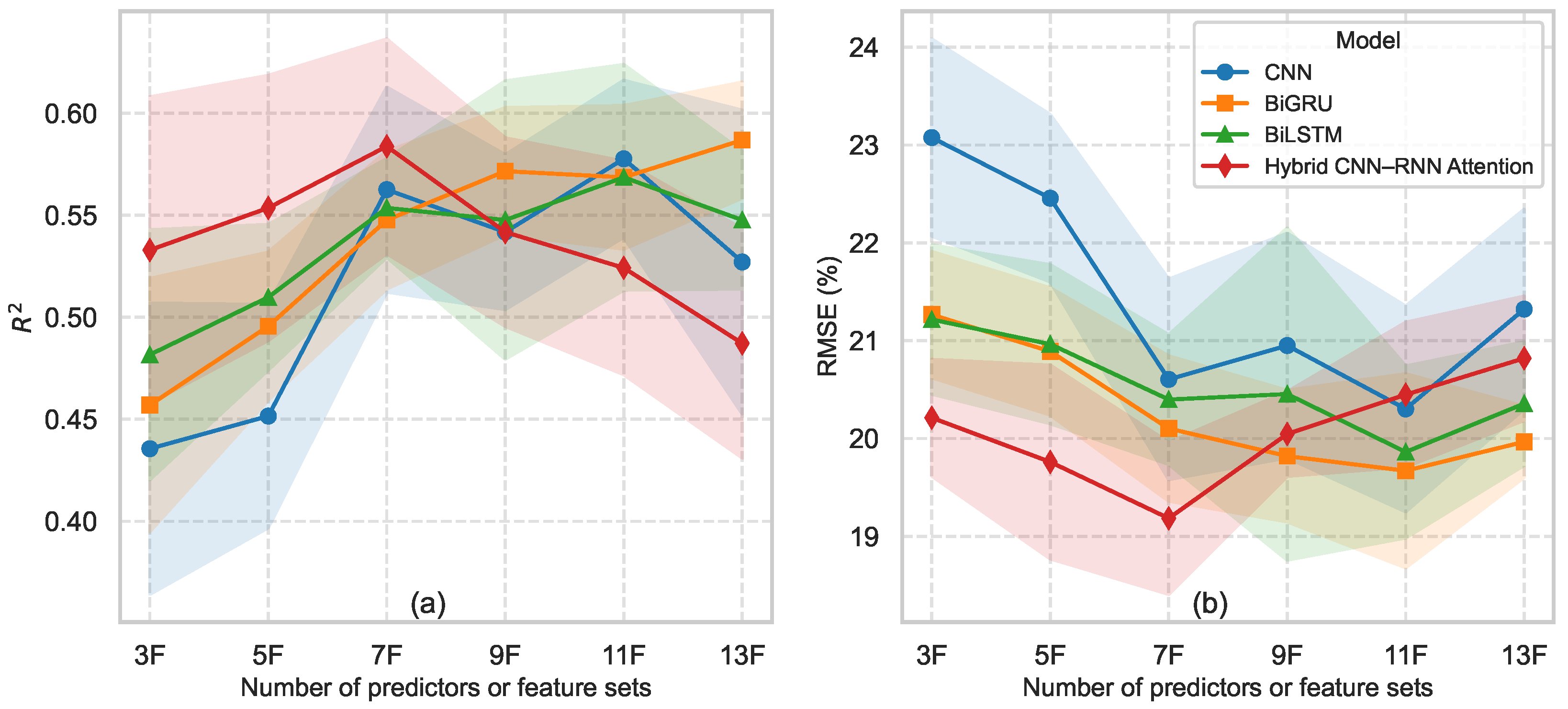

- The hybrid CNN–RNN–Attention model achieved the highest accuracy, reaching and RMSE 18% using only seven robust predictors.

- Cover crop selection is a stronger determinant of yield than fertilizer rate, informing management decisions.

- Using physiologically stable, cross-crop robust features improves model generalization and reduces redundancy in transfer learning.

- Efficient, data-sparse UAV-based yield forecasting is feasible, enabling scalable precision agriculture across root and tuber crops.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- Can TL effectively overcome the limitations of small, underrepresented datasets for sweet potato yield prediction?

- 2.

- How can canopy irregularity and spectral overlap be mitigated through feature engineering and model design?

- 3.

- Does selective fine-tuning of pretrained models improve yield prediction compared to training from scratch or traditional machine learning approaches?

2. Materials

2.1. Experimental Field, Design and In Situ Data Collection

2.2. UAV Field Imaging and Preprocessing

2.3. Feature Extraction and Dataset Preparation

3. Methodology

3.1. Transfer Learning

3.2. Hybrid Deep Transfer Learning Model Architecture

3.3. Hyperparameter, Training, Validation, and Testing

4. Transfer Learning Strategy

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Effects of Nitrogen Treatment and Cover Crops on Sweet Potato Yield

5.2. Physiological Significance, Statistical Implications, and Synthesis

5.3. Physiological Basis for Robust Feature Migration in Cross-Crop Transfer Learning

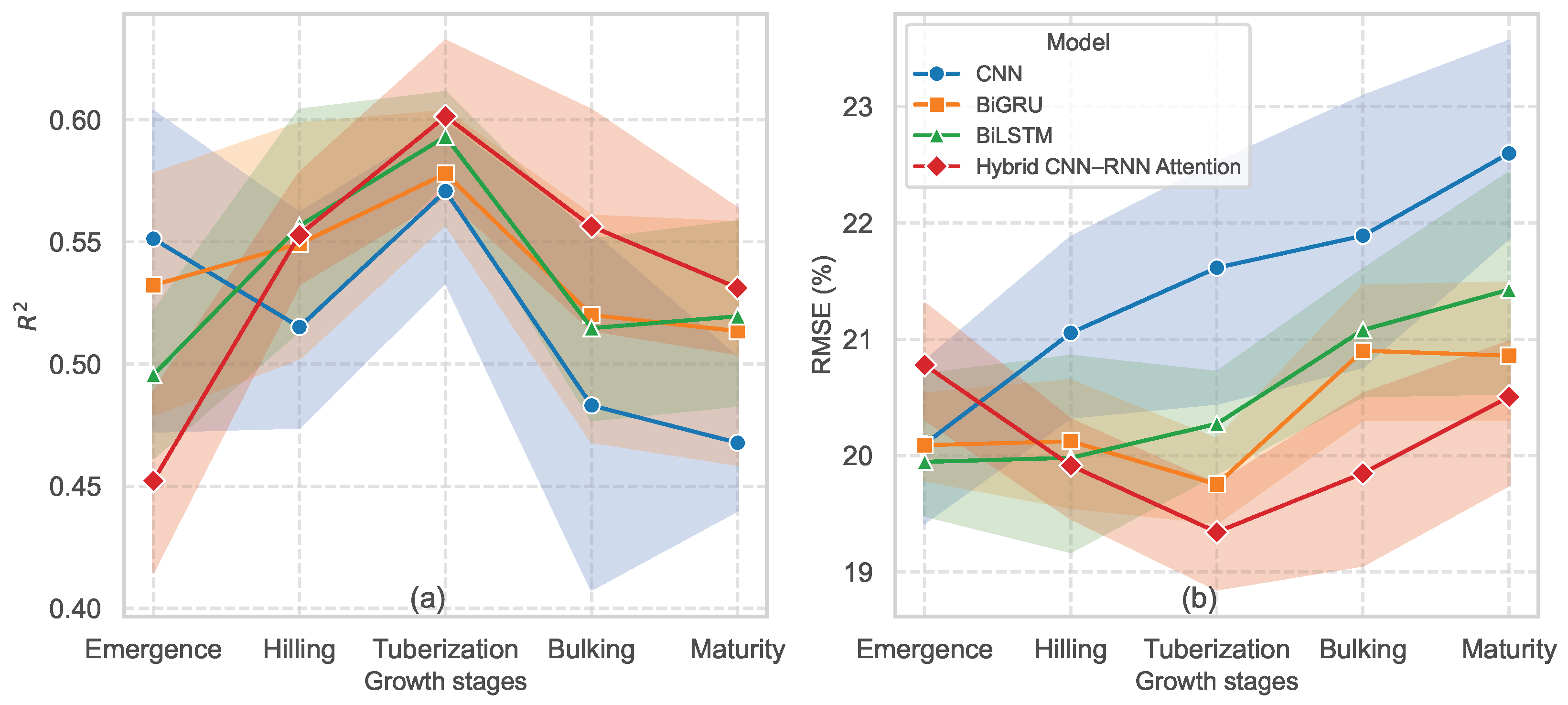

5.4. Deep Transfer Learning Model Performance

5.5. Relevance of Feature Robustness in Model Performance

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, S.; Ermon, S.; Lobell, D.B. Transfer learning in environmental remote sensing. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 301, 113924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhong, R.; Lin, Z.; Xu, J.; Jiang, H.; Huang, J.; Li, H.; Lin, T. DeepCropMapping: A multi-temporal deep learning approach with improved spatial generalizability for dynamic corn and soybean mapping. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 247, 111946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadiraju, K.K.; Vatsavai, R.R. Remote sensing based crop type classification via deep transfer learning. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 4699–4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Pradhan, B.; Chakraborty, S.; Varatharajoo, R.; Gite, S.; Alamri, A. Deep-Transfer-Learning Strategies for Crop Yield Prediction Using Climate Records and Satellite Image Time-Series Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.X.; Tran, C.; Desai, N.; Lobell, D.; Ermon, S. Deep transfer learning for crop yield prediction with remote sensing data. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCAS Conference on Computing and Sustainable Societies, Menlo Park and San Jose, CA, USA, 20–22 June 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.L.; Yang, Z. An adaptive adversarial domain adaptation approach for corn yield prediction. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Xie, B.; Yan, J.; Zhang, L.; Fan, D.; Li, L. An interpretable high-accuracy method for rice disease detection based on multisource data and transfer learning. Plants 2023, 12, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossen, M.I.; Awrangjeb, M.; Pan, S.; Mamun, A.A. Transfer learning in agriculture: A review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2025, 58, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canton, H. Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations-FAO. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2021; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Naumovski, N.; Ranadheera, C.S.; D’Cunha, N.M. Nutrition-related health outcomes of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) consumption: A systematic review. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. World Food and Agriculture Statistical Yearbook 2020; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C.; Hevesh, A.; Davis, W.V. US Sweet Potatoes Are Enjoyed Around the World, Export Data Show. 2023. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/chart-detail?chartId=105095 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- George, J.; Reddy, G.V.; Wadl, P.A.; Rutter, W.; Culbreath, J.; Lau, P.W.; Rashid, T.; Allan, M.C.; Johaningsmeier, S.D.; Nelson, A.M.; et al. Sustainable sweet potato Production in the United States: Current Status, Challenges, and Opportunities. Agron. J. 2024, 116, 630–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araus, J.L.; Cairns, J.E. Field high-throughput phenotyping: The new crop breeding frontier. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farella, A.; Paciolla, F.; Quartarella, T.; Pascuzzi, S. Agricultural unmanned ground vehicle (UGV): A brief overview. In International Symposium on Farm Machinery and Processes Management in Sustainable Agriculture; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 137–146. [Google Scholar]

- Agelli, M.; Corona, N.; Maggio, F.; Moi, P. Unmanned ground vehicles for continuous crop monitoring in agriculture: Assessing the readiness of current ICT technology. Machines 2024, 12, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, A.; Shi, Y.; Maja, J.; Peña, J. UAVs for vegetation monitoring: Overview and recent scientific contributions. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lungu, O.; Chabala, L.; Shepande, C. Satellite-based crop monitoring and yield estimation—A review. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 13, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.A.; Zhang, X.; Wijewardane, N.K.; Feldman, M.; Qin, R.; Huang, Y.; Samiappan, S.; Young, W.; Tapia, F.G. Context-Aware Deep Learning Model for Yield Prediction in Potato Using Time-Series UAS Multispectral Data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 6096–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, M.; Zeng, H.; Tian, F.; Potgieter, A.B.; Qin, X.; Yan, N.; Chang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, Q.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in remote sensing-based crop monitoring: A review. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwac290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Huang, Y.; Young, W.; Harvey, L.; Hall, M.; Zhang, X.; Lobaton, E.; Jenkins, J.; Shankle, M. Sweet Potato Yield Prediction Using Machine Learning Based on Multispectral Images Acquired from a Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Agriculture 2025, 15, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, D.; de Almeida Moreira, B.R.; Júnior, M.R.B.; Papa, J.P.; da Silva, R.P. Predicting on multi-target regression for the yield of sweet potato by the market class of its roots upon vegetation indices. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 191, 106544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hunt, S.; Yencho, G.C.; Pecota, K.V.; Mierop, R.; Williams, C.M.; Jones, D.S. Predicting sweet potato traits using machine learning: Impact of environmental and agronomic factors on shape and size. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 225, 109215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Huang, F.; Lou, W.; Gu, Q.; Ye, Z.; Hu, H.; Zhang, X. Yield prediction through UAV-based multispectral imaging and deep learning in rice breeding trials. Agric. Syst. 2025, 223, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, C.; Dhillon, J.; Huang, Y.; Reddy, K. Explainable machine learning models for corn yield prediction using UAV multispectral data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, F.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J. Progress in Research on Deep Learning-Based Crop Yield Prediction. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, D.D.; Tirado, S.B.; Springer, N.M.; Hirsch, C.N.; Hirsch, C.D. Opportunities and challenges in phenotyping row crops using drone-based RGB imaging. Plant Phenome J. 2022, 5, e20044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Liu, T.; Woznicki, S.A.; Marković, M.; Marko, O.; Sears, M. From Time-series Generation, Model Selection to Transfer Learning: A Comparative Review of Pixel-wise Approaches for Large-scale Crop Mapping. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.12590. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.M. Evaluation of vegetation indices and a modified simple ratio for boreal applications. Can. J. Remote Sens. 1996, 22, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Chivkunova, O.B.; Merzlyak, M.N. Nondestructive estimation of anthocyanins and chlorophylls in anthocyanic leaves. Am. J. Bot. 2009, 96, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Viña, A.; Ciganda, V.; Rundquist, D.C.; Arkebauer, T.J. Remote estimation of canopy chlorophyll content in crops. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondeaux, G.; Steven, M.; Baret, F. Optimization of soil-adjusted vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 55, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, D.; Baret, F.; Guyot, G. A ratio vegetation index adjusted for soil brightness. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1990, 11, 727–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baret, F.; Guyot, G. Potentials and limits of vegetation indices for LAI and APAR assessment. Remote Sens. Environ. 1991, 35, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the radiometric and biophysical performance of the MODIS vegetation indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of leaf-area index from quality of light on the forest floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.J.; Yang, Q. A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 22, 1345–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.; Inderka, A.; Steinhage, V. Leveraging remote sensing data for yield prediction with deep transfer learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Nanehkaran, Y.A. Using deep transfer learning for image-based plant disease identification. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, S.; Kamsu-Foguem, B.; Kamissoko, D.; Traore, D. Deep neural networks with transfer learning in millet crop images. Comput. Ind. 2019, 108, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki, S.; Pham, H.; Wang, L. Simultaneous corn and soybean yield prediction from remote sensing data using deep transfer learning. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketkar, N.; Moolayil, J. Convolutional neural networks. In Deep Learning with Python: Learn Best Practices of Deep Learning Models with PyTorch; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 197–242. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Nejad, S.M.M.; Abbasi-Moghadam, D.; Sharifi, A.; Farmonov, N.; Amankulova, K.; Lászlź, M. Multispectral crop yield prediction using 3D-convolutional neural networks and attention convolutional LSTM approaches. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 16, 254–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstra, J.; Bengio, Y. Random search for hyper-parameter optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2012, 13, 281–305. [Google Scholar]

- Villordon, A.Q.; La Bonte, D.R.; Firon, N.; Kfir, Y.; Pressman, E.; Schwartz, A. Characterization of adventitious root development in sweet potato. HortScience 2009, 44, 651–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villordon, A.; Solis, J.; LaBonte, D.; Clark, C. Development of a prototype Bayesian network model representing the relationship between fresh market yield and some agroclimatic variables known to influence storage root initiation in sweet potato. HortScience 2010, 45, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, R.P.; Griffin, T.S.; Honeycutt, C.W. Rotation and cover crop effects on soilborne potato diseases, tuber yield, and soil microbial communities. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, W.; Zhang, H.; Xie, B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L. Impacts of nitrogen fertilization rate on the root yield, starch yield and starch physicochemical properties of the sweet potato cultivar Jishu 25. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crews, T.E.; Peoples, M. Legume versus fertilizer sources of nitrogen: Ecological tradeoffs and human needs. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 102, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakht, J.; Shafi, M.; Jan, M.T.; Shah, Z. Influence of crop residue management, cropping system and N fertilizer on soil N and C dynamics and sustainable wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) production. Soil Tillage Res. 2009, 104, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.; Chakrabarti, S.; Makeshkumar, T.; Saravanan, R. Molecular regulation of storage root formation and development in sweet potato. Hortic. Rev. 2014, 42, 157–208. [Google Scholar]

- Dabney, S.M.; Delgado, J.A.; Meisinger, J.J.; Schomberg, H.H.; Liebig, M.A.; Kaspar, T.; Mitchell, J.; Reeves, W. Using cover crops and cropping systems for nitrogen management. Adv. Nitrogen Manag. Water Qual. 2010, 66, 231–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, A. On a measure of divergence between two statistical populations defined by their probability distribution. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 1943, 35, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Peyré, G.; Cuturi, M. Computational optimal transport: With applications to data science. Found. Trends® Mach. Learn. 2019, 11, 355–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, M.B.; Gnanadesikan, R. Probability plotting methods for the analysis for the analysis of data. Biometrika 1968, 55, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevers, J.G.; Kooistra, L.; Van den Brande, M.M. Using Sentinel-2 data for retrieving LAI and leaf and canopy chlorophyll content of a potato crop. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binte Mostafiz, R.; Noguchi, R.; Ahamed, T. Agricultural land suitability assessment using satellite Remote Sensing-derived soil-vegetation indices. Land 2021, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Date of Acquisition (mm/dd) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ine 2022 | 06/23 | 07/07 | 07/21 | 08/03 | 08/16 | 08/31 | 09/13 | 09/29 |

| 2023 | 06/28 | - | 07/19 | - | 08/11 | 08/24 | 09/13 | 09/25 |

| ine Growth Stage | Emergence | Hilling | Tuberization | Bulking | Maturity | |||

| Feature | Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 1. SR | [30] | |

| 2. MARI | [31] | |

| 3. CHLGR | [32] | |

| 4. OSAVI | [33] | |

| 5. SAVI2 | [34] | |

| 6. MSR | [30] | |

| 7. TSAVI | [35] | |

| 8. SAVI | [34] | |

| 9. EVI | [36] | |

| 10. EVI2 | [36] | |

| 11. DVI | [37] | |

| 12. Spatial ( | [20] | |

| 13. Agronomic () | Nitrogen fertilization |

| Source | df | SS | MS | F | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen () | 4 | 1.12 | 2.79 | 0.824 | 0.513 |

| Cover Crop | 2 | 3.96 | 1.98 | 5.83 | 0.00397 ** |

| × Cover Crop | 8 | 5.32 | 6.64 | 1.96 | 0.0588 † |

| Residual | 105 | 3.56 | 3.39 | — | — |

| Growth Stages | 3F | 5F | 7F | 9F | 11F | 13F | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | |||||||

| Emergence | 0.37 | 21.60% | 0.53 | 21.05% | 0.61 | 19.57% | 0.58 | 19.21% | 0.61 | 19.40% | 0.61 | 19.77% |

| Hilling | 0.46 | 22.65% | 0.44 | 21.91% | 0.52 | 20.44% | 0.50 | 20.74% | 0.59 | 19.65% | 0.58 | 20.94% |

| Tuberization | 0.56 | 22.75% | 0.49 | 22.85% | 0.59 | 20.98% | 0.58 | 22.79% | 0.62 | 19.32% | 0.58 | 21.00% |

| Bulking | 0.36 | 23.94% | 0.37 | 23.16% | 0.61 | 19.66% | 0.56 | 20.75% | 0.53 | 21.34% | 0.46 | 22.49% |

| Maturity | 0.44 | 24.44% | 0.44 | 23.31% | 0.49 | 22.37% | 0.49 | 21.26% | 0.53 | 21.80% | 0.42 | 22.41% |

| Growth Stages | 3F | 5F | 7F | 9F | 11F | 13F | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | |||||||

| Emergence | 0.42 | 21.15% | 0.49 | 20.15% | 0.53 | 19.93% | 0.59 | 19.74% | 0.59 | 19.76% | 0.56 | 19.81% |

| Hilling | 0.52 | 20.59% | 0.45 | 21.28% | 0.58 | 19.69% | 0.58 | 19.05% | 0.53 | 20.33% | 0.64 | 19.80% |

| Tuberization | 0.55 | 20.58% | 0.56 | 20.05% | 0.56 | 19.51% | 0.61 | 19.15% | 0.62 | 19.53% | 0.56 | 19.70% |

| Bulking | 0.42 | 21.85% | 0.49 | 21.51% | 0.49 | 21.56% | 0.56 | 20.41% | 0.56 | 20.25% | 0.59 | 19.83% |

| Maturity | 0.38 | 22.16% | 0.49 | 21.46% | 0.58 | 19.82% | 0.52 | 20.75% | 0.53 | 20.28% | 0.58 | 20.69% |

| Growth Stages | 3F | 5F | 7F | 9F | 11F | 13F | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | |||||||

| Emergence | 0.41 | 21.79% | 0.52 | 19.74% | 0.53 | 19.51% | 0.52 | 19.58% | 0.50 | 19.31% | 0.49 | 19.75% |

| Hilling | 0.50 | 20.24% | 0.48 | 21.52% | 0.56 | 19.76% | 0.64 | 18.68% | 0.62 | 18.75% | 0.53 | 20.94% |

| Tuberization | 0.59 | 20.35% | 0.58 | 20.29% | 0.58 | 20.52% | 0.62 | 19.64% | 0.62 | 19.56% | 0.56 | 21.28% |

| Bulking | 0.45 | 21.66% | 0.49 | 21.90% | 0.58 | 21.09% | 0.49 | 20.80% | 0.50 | 21.23% | 0.58 | 19.80% |

| Maturity | 0.46 | 22.04% | 0.49 | 21.37% | 0.52 | 21.11% | 0.48 | 23.57% | 0.59 | 20.46% | 0.58 | 20.01% |

| Growth Stages | 3F | 5F | 7F | 9F | 11F | 13F | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | RMSE (%) | |||||||

| Emergence | 0.38 | 20.70% | 0.46 | 20.42% | 0.49 | 20.22% | 0.52 | 20.17% | 0.44 | 21.30% | 0.37 | 21.87% |

| Hilling | 0.55 | 20.10% | 0.53 | 20.28% | 0.61 | 18.91% | 0.56 | 20.33% | 0.55 | 20.98% | 0.52 | 20.42% |

| Tuberization | 0.56 | 19.61% | 0.59 | 19.31% | 0.64 | 18.18% | 0.62 | 19.31% | 0.59 | 19.45% | 0.52 | 20.17% |

| Bulking | 0.58 | 19.57% | 0.66 | 18.03% | 0.58 | 19.55% | 0.52 | 19.86% | 0.52 | 20.28% | 0.49 | 20.84% |

| Maturity | 0.49 | 21.08% | 0.53 | 20.76% | 0.61 | 18.66% | 0.49 | 20.56% | 0.53 | 20.97% | 0.53 | 21.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yadav, S.A.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, K.Q.; Haque, R.; Young, W.; Harvey, L.; Hall, M.; Zhang, X.; Wijewardane, N.K.; Qin, R.; et al. Deep Transfer Learning for UAV-Based Cross-Crop Yield Prediction in Root Crops. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244054

Yadav SA, Huang Y, Zhu KQ, Haque R, Young W, Harvey L, Hall M, Zhang X, Wijewardane NK, Qin R, et al. Deep Transfer Learning for UAV-Based Cross-Crop Yield Prediction in Root Crops. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244054

Chicago/Turabian StyleYadav, Suraj A., Yanbo Huang, Kenny Q. Zhu, Rayyan Haque, Wyatt Young, Lorin Harvey, Mark Hall, Xin Zhang, Nuwan K. Wijewardane, Ruijun Qin, and et al. 2025. "Deep Transfer Learning for UAV-Based Cross-Crop Yield Prediction in Root Crops" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244054

APA StyleYadav, S. A., Huang, Y., Zhu, K. Q., Haque, R., Young, W., Harvey, L., Hall, M., Zhang, X., Wijewardane, N. K., Qin, R., Feldman, M., Yao, H., & Brooks, J. P. (2025). Deep Transfer Learning for UAV-Based Cross-Crop Yield Prediction in Root Crops. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4054. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244054

_Qin.png)