Quantifying Broad-Leaved Korean Pine Forest Structure Using Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), Changbai Mountain, China

Highlights

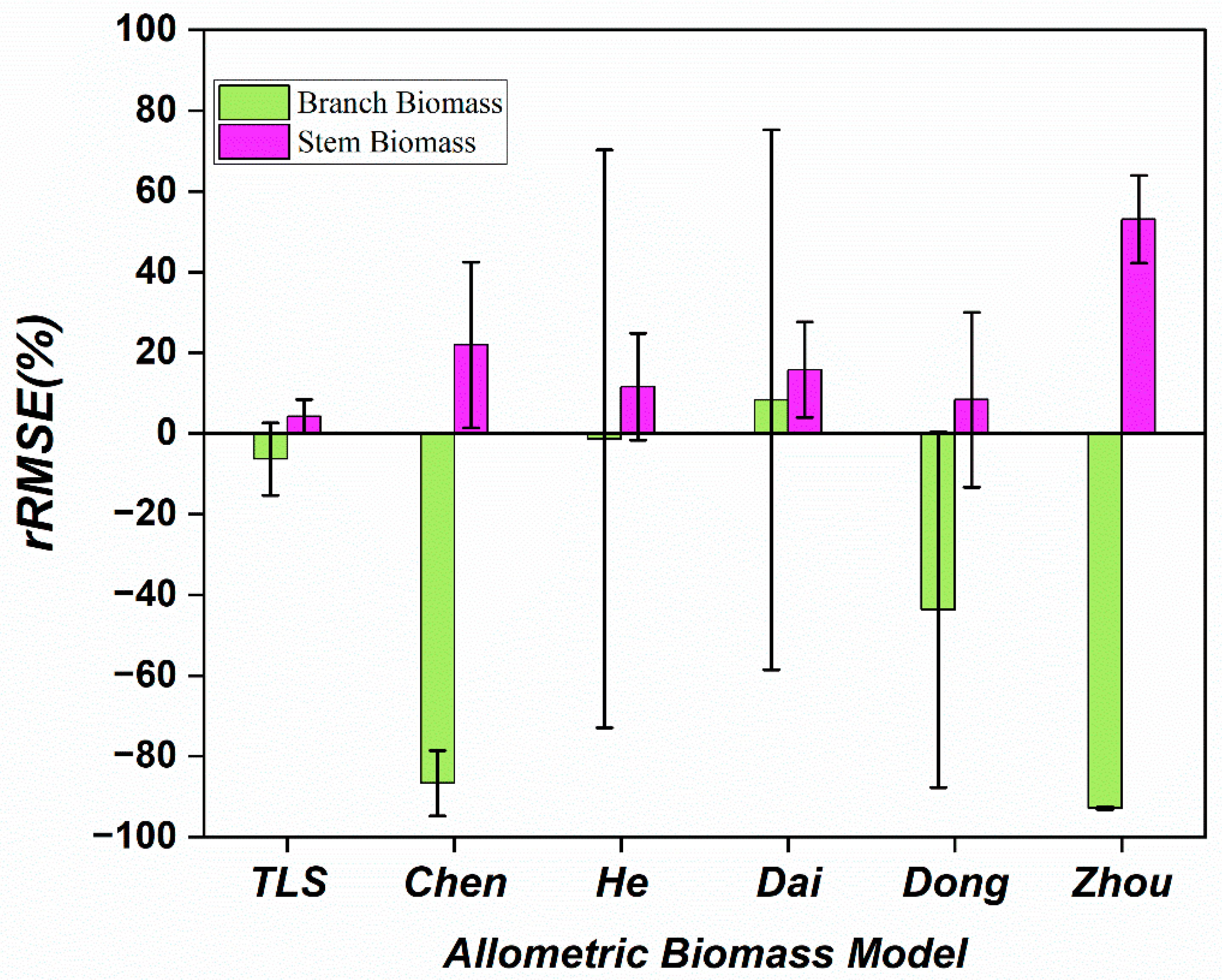

- This study proposes a method for constructing allometric models of tree stems and branches using a terrestrial laser scanning and quantitative structural model (TLS-QSM) and compares it with traditional allometric models. The results indicate that traditional models generally overestimate stem biomass and significantly underestimate branch biomass, with a deviation range of −1.34% to 92.85%.

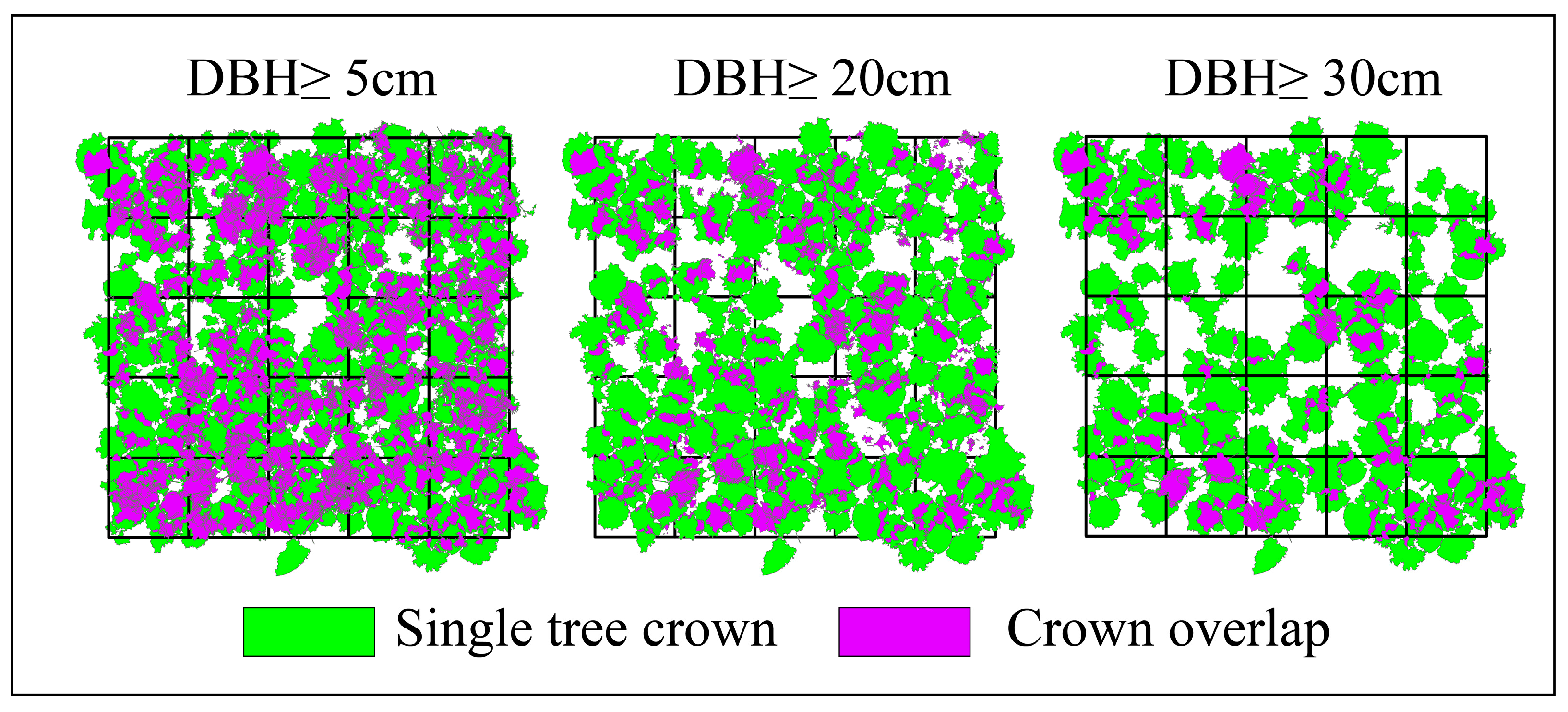

- The crown overlap rate within a 1-hectare plot (DBH ≥ 5 cm) was quantified as 59.1%. Furthermore, it was observed that the crown overlap rate gradually decreases as tree size increases.

- The study provides an effective alternative for developing and improving allometric equations and establishes a solid foundation for future development and application of allometric models.

- Crown overlap rate serves as a key indicator for assessing both vertical and horizontal forest structure. It offers scientific insights into revealing differences in competitive pressure within communities, evaluating the stability and dynamics of forest ecosystems, guiding forest management practices, and understanding complex interactions within forest communities.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

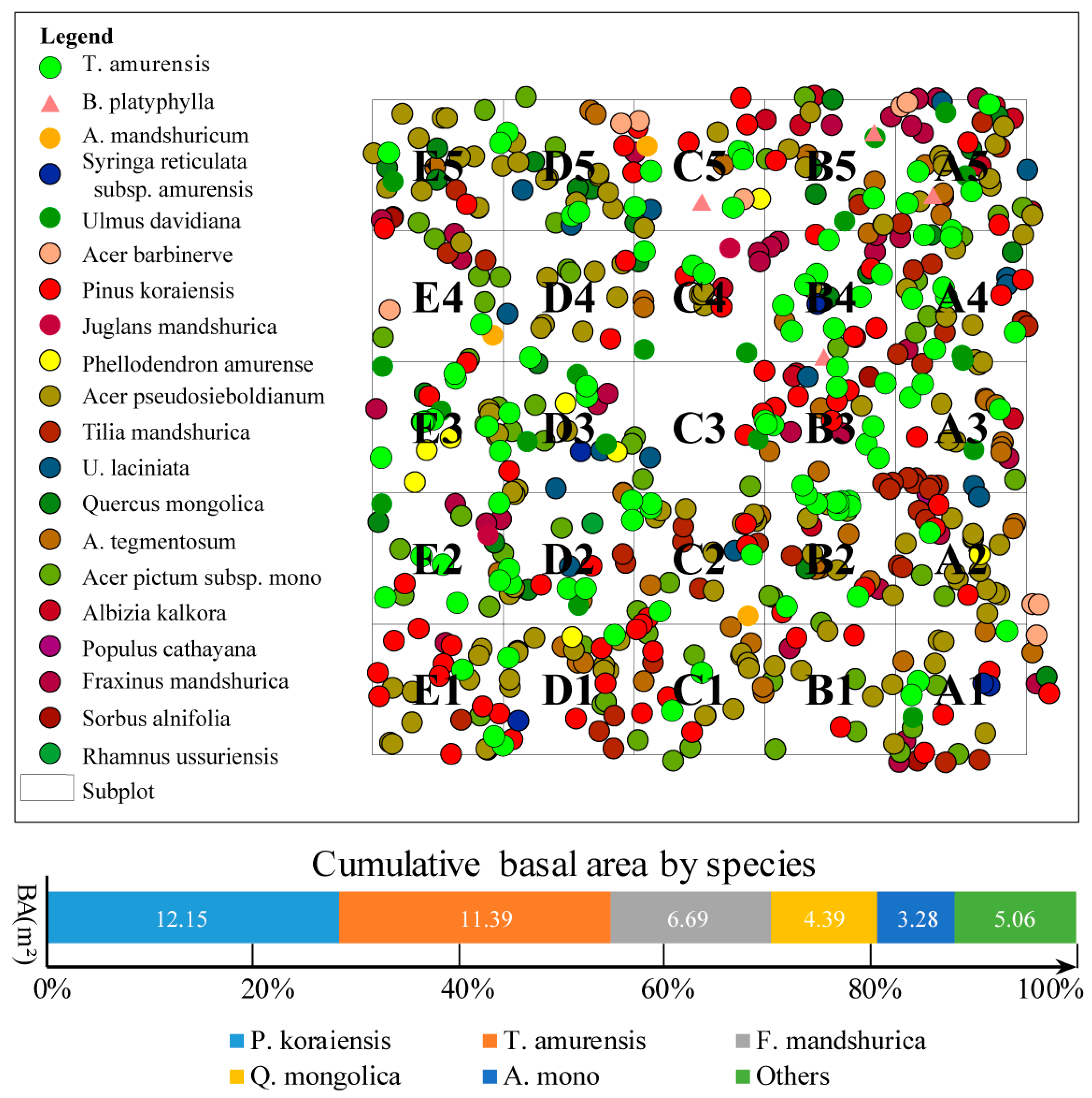

2.2. Plot Setup and Data Collection

2.3. TLS Point Cloud Data Processing

2.4. Estimation of Individual Tree Volume and Biomass

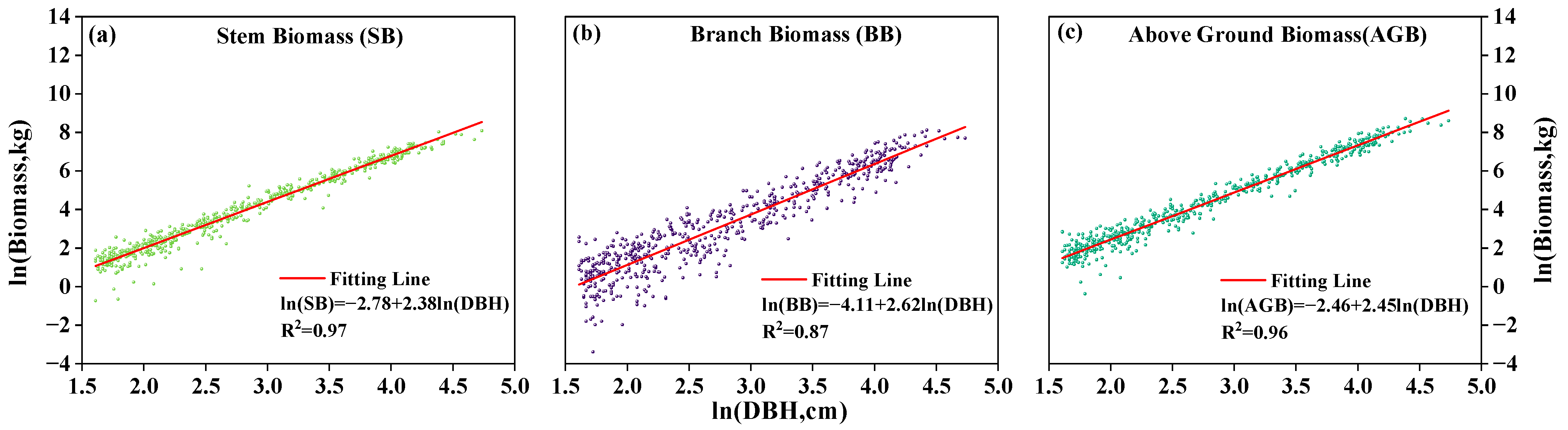

2.5. Biomass Model Construction Using TLS Point Cloud Data

2.6. Data Processing

3. Results

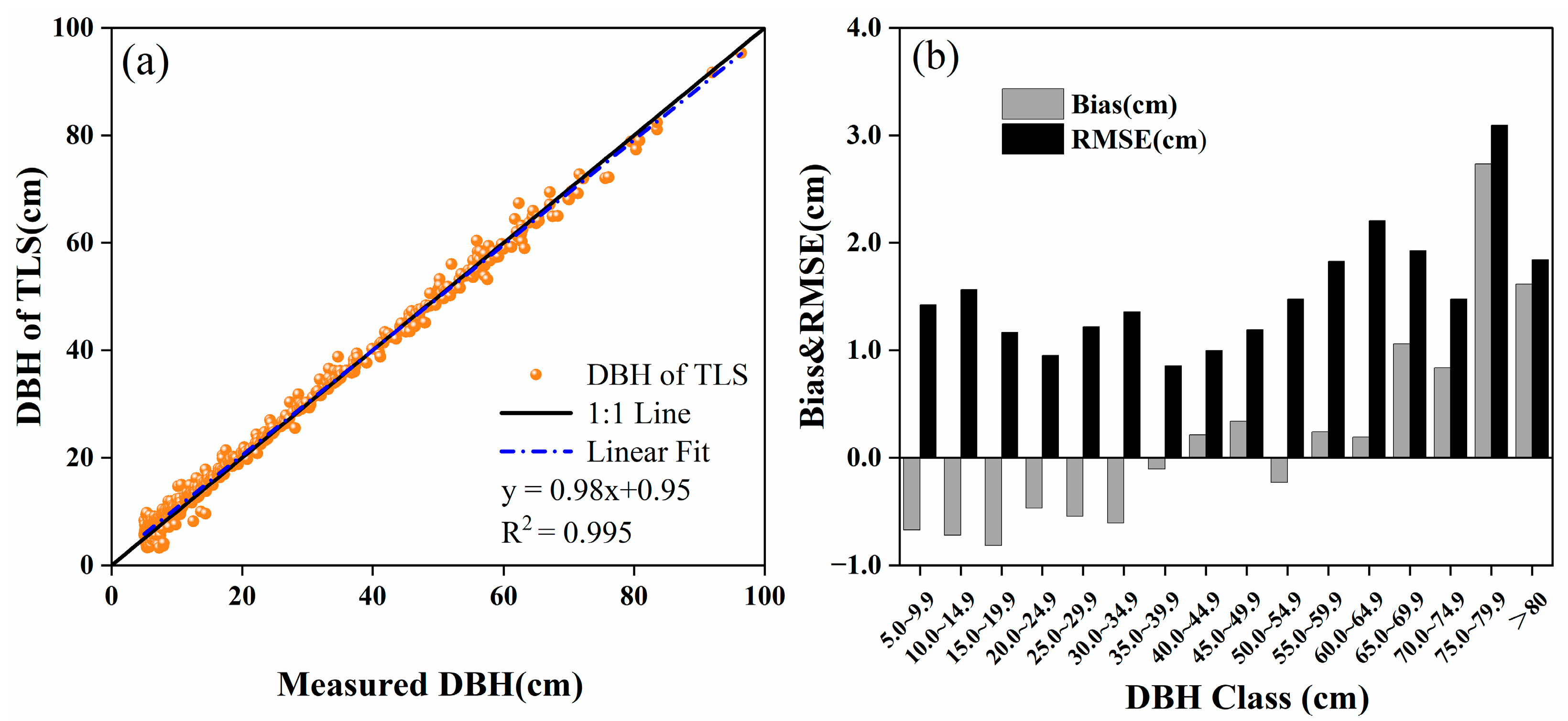

3.1. Accuracy of TLS Point Cloud Inversion

3.2. Dendrometric Information of Broadleaf Korean Pine Forest

3.3. The Relationship Between Canopy Spread, Volume, Biomass, and DBH

3.4. Development and Validation of a TLS-Derived Stem Biomass Model

3.5. Performance of Different Biomass Models

4. Discussion

4.1. TLS Inversion Accuracy

4.2. Using TLS for Assessing Forest Vertical Structure at High Resolution

4.3. Convergence Trends in Allometric Growth Across Tree Species in Primary Forests

4.4. Simulation and Modeling of Stand Structural Parameters Using TLS Technology

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Taxon | DBH Range (cm) | Component | Biomass Equations | Literature Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. koraiensis | 1.0–75.0 | Branch | B = 0.01637 × (DBH) 2.045 | Chen |

| Stem | B = 0.03019 × (DBH) 2.679 | |||

| 8.4–44.0 | Branch | ln(B) = −4.306 + 2.527 × ln (DBH) | He | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −3.394 + 2.582 × ln (DBH) | |||

| 7.3–82.0 | Branch | ln(B) = −3.3911 + 2.006 × ln (DBH) | Dong | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −2.2319 + 2.235 × ln (DBH) | |||

| 8.4–44.0 | Branch | B = 0.013 × (DBH) 2.527 | Dai | |

| Stem | B = 0.033 × (DBH) 2.582 | |||

| 5.0–150.0 | Branch | B = 0.0208 × (DBH) 1.9612 | Zhou | |

| Stem | B = 0.0418 × (DBH) 2.5919 | |||

| T. amurosis | 1.0–70.0 | Branch | B = 0.00472 × (DBH) 2.546 | Chen |

| Stem | B = 0.0656 × (DBH) 2.391 | |||

| 7.0–42.0 | Branch | ln(B) = −6.171 + 3.131 ln (DBH) | He | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −2.364 + 2.323 ln (DBH) | |||

| 6.8–37.0 | Branch | ln(B) = −5.0391 + 2.567 ln (DBH) | Dong | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −3.2077 + 2.615 ln (DBH) | |||

| 7.0–42.2 | Branch | ln(B) = 0.02 + 3.13 × ln (DBH) | Dai | |

| Stem | ln(B) = 0.094 + 2.322 ×ln (DBH) | |||

| Q. mongolica | 1.0–74.0 | Branch | B = 0.00212 × (DBH) 2.95 | Chen |

| Stem | B = 0.3048 × (DBH) 2.168 | |||

| 4.2–37.1 | Branch | ln(B) = −6.997 + 3.522 ×ln (DBH) | Dong | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −2.5856 + 2.486 × ln (DBH) | |||

| 5.0–90.0 | Branch | B = 0.0098 × (DBH) 2.2928 | Zhou | |

| Stem | B = 0.2053 × (DBH) 2.2928 | |||

| F. mandshurica | 10.7~41.4 | Branch | ln(B) = −6.989 + 3.481 ln (DBH) | He |

| Stem | ln(B) = −2.301 + 2.443 ln (DBH) | |||

| 5.7–33.4 | Branch | ln(B) = −5.5012 + 2.93 ln (DBH) | Dong | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −2.8496 + 2.511 ln (DBH) | |||

| 4.7–41.4 | Branch | B = 0.0009 × (DBH) 3.481 | Dai | |

| Stem | B = 0.1 × (DBH) 2.442 | |||

| A. mono | 1.0–45.0 | Branch | B = 0.05579 × (DBH) 1.66 | Chen |

| Stem | B = 1.3709 × (DBH) 1.671 | |||

| 6.4–45.3 | Branch | ln(B) = −3.948 + 1.81 ln (DBH) | He | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −4.645 + 2.741 ln (DBH) | |||

| 4.8–32.5 | Branch | ln(B) = −3.3225 + 2.274 ln (DBH) | Dong | |

| Stem | ln(B) = −2.2812 + 2.377 ln (DBH) |

Appendix A.2

| Branch/Stem of Specices | Model | R2 | Fitting Equation | RMSE (kg) | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. koraiensis Branch | TLS | 0.71 | y = 0.5901x + 137.1098 | 297.91 | Slope: [0.5149–0.6652] Intercept: [137.0975–137.1222] |

| Chen | −0.75 | y = 0.0426x + 18.3105 | 727.36 | Slope: [0.0369–0.0483] Intercept: [18.3095–18.3114] | |

| He | 0.39 | y = 0.3850x + 91.7280 | 431.49 | Slope: [0.3359–0.4340] Intercept: [91.7199–91.7360] | |

| Dong | −0.59 | y = 0.0739x + 33.1534 | 693.29 | Slope: [0.0639–0.0839] Intercept: [33.1518–33.1551] | |

| Dai | 0.12 | y = 0.2833x + 67.4928 | 515.74 | Slope: [0.2472–0.3194] Intercept: [67.4869–67.4988] | |

| Zhou | −0.77 | y = 0.0373x + 17.6015 | 731.90 | Slope: [0.0322–0.0424] Intercept: [17.6007–17.6023] | |

| P. koraiensis Stem | TLS | 0.88 | y = 1.0089x − 9.7219 | 166.39 | Slope: [0.9254–1.0924] Intercept: [−9.7384−9.7053] |

| Chen | −0.10 | y = 1.5919x − 86.9800 | 493.35 | Slope: [1.4511–1.7326] Intercept: [−87.0079–86.9521] | |

| He | 0.78 | y = 1.1615x − 38.5517 | 221.77 | Slope: [1.0622–1.2607] Intercept: [−38.5714–38.5320] | |

| Dong | 0.87 | y = 0.8223x + 45.8712 | 167.51 | Slope: [0.7582–0.8864] Intercept: [45.8585–45.8839] | |

| Dai | 0.80 | y = 1.1416x − 37.8924 | 212.30 | Slope: [1.0441–1.2391] Intercept: [−37.9118–37.8731] | |

| Zhou | 0.10 | y = 1.5096x − 53.5036 | 447.15 | Slope: [1.3802–1.6390] Intercept: [−53.5293–53.4780] | |

| Q. mongolica Branch | TLS | 0.49 | y = 0.3897x + 578.7640 | 1809.69 | Slope: [0.2488–0.5306]\ Intercept: [578.7282–578.7999] |

| Chen | −0.13 | y = 0.1004x + 166.8264 | 2701.39 | Slope: [0.0636–0.1371] Intercept: [166.8170–166.8357] | |

| Dong | 0.60 | y = 0.5361x + 749.1457 | 1600.48 | Slope: [0.3428–0.7293] Intercept: [749.0966–749.1949] | |

| Zhou | 0.04 | y = 0.1542x + 278.0584 | 2491.07 | Slope: [0.0968–0.2115] Intercept: [278.0438–278.0730] | |

| Q. mongolica Stem | TLS | 0.94 | y = 0.9785x + 46.0558 | 280.60 | Slope: [0.8678–1.0892] Intercept: [46.0205–46.0910] |

| Chen | 0.89 | y = 1.0774x + 35.4132 | 373.78 | Slope: [0.9441–1.2108] Intercept: [35.3708–35.4557] | |

| Dong | 0.93 | y = 0.9843x + 8.3663 | 291.96 | Slope: [0.8687–1.0998] Intercept: [8.3295–8.4031] | |

| Zhou | 0.18 | y = 1.5110x + 68.1196 | 1038.45 | Slope: [1.3399–1.6822] Intercept: [68.0651–68.1741] | |

| F. mandshurica Branch | TLS | 0.85 | y = 1.1171x − 36.5019 | 318.48 | Slope: [0.9874–1.2469] Intercept: [−36.5295–36.4743] |

| He | −4.44 | y = 2.8077x − 372.6171 | 1948.61 | Slope: [2.3824–3.2330] Intercept: [−372.7077–372.5266] | |

| Dong | 0.88 | y = 0.9779x − 58.3754 | 288.92 | Slope: [0.8575–1.0982] Intercept: [−58.4010–58.3498] | |

| Dai | −4.07 | y = 2.7408x − 363.7387 | 1881.27 | Slope: [2.3257–3.1560] Intercept: [−363.8270–363.6503] | |

| F. mandshurica Stem | TLS | 0.86 | y = 1.1899x − 165.3059 | 478.39 | Slope: [1.0750–1.3049] Intercept: [−165.3331–165.2787] |

| He | 0.17 | y = 1.6472x − 363.9230 | 1160.37 | Slope: [1.4505–1.8439] Intercept: [−363.9696–363.8764] | |

| Dong | 0.71 | y = 1.2969x − 310.5829 | 691.55 | Slope: [1.1342–1.4596] Intercept: [−310.6215–310.5444] | |

| Dai | 0.19 | y = 1.6372x − 361.2383 | 1144.89 | Slope: [1.4418–1.8325] Intercept: [−361.2846–361.1920] | |

| A. mono Branch | TLS | 0.91 | y = 0.8979x + 13.7680 | 119.65 | Slope: [0.8212–0.9745] Intercept: [13.7563–13.7798] |

| Chen | −0.25 | y = 0.0301x + 5.0347 | 443.12 | Slope: [0.0263–0.0339] Intercept: [5.0341–5.0352] | |

| He | 0.61 | y = 0.4826x − 3.8544 | 247.06 | Slope: [0.4417–0.5235] Intercept: [−3.8607–3.8481] | |

| Dong | 0.27 | y = 0.2549x + 12.4212 | 337.92 | Slope: [0.2317–0.2780] Intercept: [12.4176–12.4247] | |

| A. mono Stem | TLS | 0.89 | y = 1.1729x − 46.8728 | 126.85 | Slope: [1.0985–1.2472] Intercept: [−46.8853–46.8603] |

| Chen | 0.96 | y = 0.8572x + 47.7333 | 74.34 | Slope: [0.8232–0.8912] Intercept: [47.7276–47.7390] | |

| He | 0.92 | y = 1.0943x − 44.4406 | 108.46 | Slope: [1.0244–1.1641] Intercept: [−44.4523–44.4289] | |

| Dong | 0.90 | y = 1.1515x − 51.7855 | 126.07 | Slope: [1.0744–1.2285] Intercept: [−51.7985–51.7726] | |

| T. amurensis Branch | TLS | 0.63 | y = 0.8516x + 25.9703 | 472.38 | Slope: [0.7304–0.9728] Intercept: [25.9560–25.9847] |

| Chen | −0.04 | y = 0.1100x + 11.7515 | 793.38 | Slope: [0.0965–0.1236] Intercept: [11.7499–11.7531] | |

| He | 0.63 | y = 0.6427x + 12.1711 | 474.18 | Slope: [0.5484–0.7370] Intercept: [12.1599–12.1823] | |

| Dong | 0.09 | y = 0.1657x + 17.0508 | 743.33 | Slope: [0.1452–0.1862] Intercept: [17.0484–17.0533] | |

| Dai | 0.62 | y = 0.6125x + 11.6742 | 480.72 | Slope: [0.5227–0.7024] Intercept: [11.6635–11.6848] | |

| T. amurensis Stem | TLS | 0.81 | y = 1.0293x − 2.8292 | 276.20 | Slope: [0.9387–1.1198] Intercept: [−2.8409–2.8176] |

| Chen | 0.79 | y = 1.0042x − 23.8290 | 286.27 | Slope: [0.9103–1.0980] Intercept: [−23.8411–23.8169] | |

| He | 0.78 | y = 1.0687x − 13.9628 | 297.91 | Slope: [0.9720–1.1655] Intercept: [−13.9753–13.9504] | |

| Dong | −0.23 | y = 1.6518x − 90.4395 | 699.16 | Slope: [1.4796–1.8239] Intercept: [−90.4616–90.4173] | |

| Dai | 0.78 | y = 1.0636x − 13.7234 | 295.79 | Slope: [0.9673–1.1598] Intercept: [−13.7357–13.7110] |

References

- Stephenson, N.L.; Das, A.J.; Condit, R.; Russo, S.E.; Baker, P.J.; Beckman, N.G.; Coomes, D.A.; Lines, E.R.; Morris, W.K.; Rüger, N.; et al. Rate of Tree Carbon Accumulation Increases Continuously with Tree Size. Nature 2014, 507, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Lamy, T.; Wang, S.; Hautier, Y.; Geng, Y.; White, H.J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; et al. Latitudinal Patterns of Forest Ecosystem Stability across Spatial Scales as Affected by Biodiversity and Environmental Heterogeneity. Global Change Biol. 2023, 29, 2242–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, A.; Chaudhary, P.; Mankotia, S. Impacts of Climate Change on Forest Ecosystem Dynamics and Management Strategies. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maure, L.A.; Diniz, M.F.; Pacheco Coelho, M.T.; Molin, P.G.; Rodrigues da Silva, F.; Hasui, E. Biodiversity and Carbon Conservation under the Ecosystem Stability of Tropical Forests. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Hu, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wu, J.; Maeda, E.E.; Ju, W.; Liu, L.; Guo, Q.; et al. Enhancing Ecosystem Productivity and Stability with Increasing Canopy Structural Complexity in Global Forests. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadl1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieczynski, D.J.; Boyle, B.; Buzzard, V.; Duran, S.M.; Henderson, A.N.; Hulshof, C.M.; Kerkhoff, A.J.; McCarthy, M.C.; Michaletz, S.T.; Swenson, N.G.; et al. Climate Shapes and Shifts Functional Biodiversity in Forests Worldwide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Fernández, D.; Oliveira, N.; Myllymäki, M.; Cañellas, I.; Kuronen, M.; Alberdi, I. Evaluation of the Performance of Forest Structural Indices under Different National Forest Inventory Plot Designs. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 181, 114434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, H.; Zhu, J. An ICESat-2 Photon Cloud Classification Model Coupling Slope and Complex Canopy Structure in Forest Areas. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 331, 115022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhen, Z.; Zhao, Y.H. Stand spatial structure characterization of broad-leaved Pinus koraiensis forest based on multi-source LiDAR data. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2023, 43, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Tian, X.; Wang, H. Integrating Species Functional and Architectural Traits for Improving Crown Width Prediction in Subtropical Multispecies Forests Using Nonlinear Hierarchical Models. Ecol. Inf. 2025, 90, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, M.; Latifi, H.; Iranmanesh, Y. Geometry-Based Point Cloud Fusion of Dual-Layer UAV Photogrammetry and a Modified Unsupervised Generative Adversarial Network for 3D Tree Reconstruction in Semi-Arid Forests. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 239, 111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagoke, A.; Proisy, C.; Féret, J.-B.; Blanchard, E.; Fromard, F.; Mehlig, U.; De Menezes, M.M.; Dos Santos, V.F.; Berger, U. Extended Biomass Allometric Equations for Large Mangrove Trees from Terrestrial LiDAR Data. Trees 2016, 30, 935–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovall, A.E.L.; Vorster, A.; Anderson, R.; Evangelista, P. Developing Nondestructive Species-specific Tree Allometry with Terrestrial Laser Scanning. Methods Ecol Evol 2023, 14, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncanson, L.; Armston, J.; Disney, M.; Avitabile, V.; Barbier, N.; Calders, K.; Carter, S.; Chave, J.; Herold, M.; Crowther, T.W.; et al. The Importance of Consistent Global Forest Aboveground Biomass Product Validation. Surv. Geophys. 2019, 40, 979–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Dong, X.; Liu, W.; Lin, W. Modeling Biomass of White Birch in the Lesser Khingan Range of China Based on Terrestrial 3D Laser Scanning System. Nat. Resour. Model. 2020, 33, e12240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudermilk, E.L.; Pokswinski, S.; Hawley, C.M.; Maxwell, A.; Gallagher, M.R.; Skowronski, N.S.; Hudak, A.T.; Hoffman, C.; Hiers, J.K. Terrestrial Laser Scan Metrics Predict Surface Vegetation Biomass and Consumption in a Frequently Burned Southeastern US Ecosystem. Fire 2023, 6, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muumbe, T.P.; Singh, J.; Baade, J.; Raumonen, P.; Coetsee, C.; Thau, C.; Schmullius, C. Individual Tree-Scale Aboveground Biomass Estimation of Woody Vegetation in a Semi-Arid Savanna Using 3D Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodas, D.S.; Brazolin, S.; Velasco, G.D.N.; de Lima, R.A.; Yojo, T.; Papa, J.P. Urban Tree Failure Probability Prediction Based on Dendrometric Aspects and Machine Learning Models. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2024, 108, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Xiao, W.; Du, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, X. Automatic Detection Tree Crown and Height Using Mask R-CNN Based on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Images for Biomass Mapping. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 555, 121712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, M.; Fichtner, A.; Härdtle, W.; Raumonen, P.; Bruelheide, H.; von Oheimb, G. Neighbour Species Richness and Local Structural Variability Modulate Aboveground Allocation Patterns and Crown Morphology of Individual Trees. Ecol. Lett. 2019, 22, 2130–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Fan, G.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F. Low Cost Automatic Reconstruction of Tree Structure by AdQSM with Terrestrial Close-Range Photogrammetry. Forests 2021, 12, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Bentley, L.P.; Martius, C.; Shenkin, A.; Bartholomeus, H.; Raumonen, P.; Malhi, Y.; Jackson, T.; Herold, M. Quantifying Branch Architecture of Tropical Trees Using Terrestrial LiDAR and 3D Modelling. Trees 2018, 32, 1219–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornand, A.; Rehush, N.; Morsdorf, F.; Thürig, E.; Abegg, M. Individual Tree Volume Estimation with Terrestrial Laser Scanning: Evaluating Reconstructive and Allometric Approaches. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 341, 109654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez De Tanago, J.; Lau, A.; Bartholomeus, H.; Herold, M.; Avitabile, V.; Raumonen, P.; Martius, C.; Goodman, R.C.; Disney, M.; Manuri, S.; et al. Estimation of Above-ground Biomass of Large Tropical Trees with Terrestrial LiDAR. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Qi, L.; Wang, Q.; Su, D.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, W. Changes in Forest Structure and Composition on Changbai Mountain in Northeast China. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurjević, L.; Liang, X.; Gašparović, M.; Balenović, I. Is Field-Measured Tree Height as Reliable as Believed—Part II, a Comparison Study of Tree Height Estimates from Conventional Field Measurement and Low-Cost Close-Range Remote Sensing in a Deciduous Forest. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 169, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongya, H.; Lihai, W.; Huadong, X.; Shiquan, S.; Tianyong, S. Error Analysis of Tree Height Estimation Based on Eye Measurement. For. Eng. 2012, 28, 6–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, S.; Mölder, I.; Jacob, M.; Gebauer, T.; Jungkunst, H.F.; Leuschner, C. Comparison of Conventional Eight-Point Crown Projections with LIDAR-Based Virtual Crown Projections in a Temperate Old-Growth Forest. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 1173–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Jin, G. Impacts of Stand Density on Tree Crown Structure and Biomass: A Global Meta-Analysis. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 326, 109181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condés, S.; Aguirre, A.; del Río, M. Crown Plasticity of Five Pine Species in Response to Competition along an Aridity Gradient. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 473, 118302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, Y.; Yan, Y.; He, P.; Jiang, L. Tree Size Inequality and Precipitation Modulate the Effect of Functional Diversity on Height to Crown Base in Uneven-Aged Mixed Forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 595, 123049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J.W.; Bhatt, P.; Carrasco, L.; Francis, E.; Garabedian, J.E.; Hakkenberg, C.R.; Hardiman, B.S.; Jung, J.; Koirala, A.; LaRue, E.A.; et al. Integrating Forest Structural Diversity Measurement into Ecological Research. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Yang, H.; Shu, Q.; Yu, J.; Xu, L.; Wang, M.; Xia, C.; Duan, D. Estimation of Leaf Area Index for Dendrocalamus Giganteus Based on Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Forests 2024, 15, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.G.; Zhu, J.F. Handbook of Biomass of Main Trees in Northeast China; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Fousseni, F.; Wang, J.; Dai, H.; Yang, S.; Zuo, Q. Allometric Biomass Equations for 12 Tree Species in Coniferous and Broadleaved Mixed Forests, Northeastern China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0186226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H. Allometric Models of Dominant Tree Species in Korean Pine Broadleaf Forest in Jiaohe, Jilin Province. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L. Developing Individual and Stand-Level Biomass Equation in Northeast China Forest Area. Doctoral Dissertation, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Yin, G.; Tang, X.; Wen, D.; Liu, C.; Kuang, Y.; Wang, W. Carbon Storage in China’s Forest Ecosystems: Biomass Equations; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Du, W.; Zhou, G.; Qin, L.; Meng, S.; Yu, J.; Sun, Z.; SiQing, B.; Liu, Q. Aboveground Biomass Allocation and Additive Allometric Models of Fifteen Tree Species in Northeast China Based on Improved Investigation Methods. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 505, 119918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terryn, L.; Ellsworth, D.; Medlyn, B.E.; Boer, M.; Verhelst, T.E.; Calders, K. New-Allometric-Models-for-Eucalyptus-Tereticornis-Using-Terrestrial-Laser-Scanning-Show-Increased-Carbon-Storage-in-Larger-Trees. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2025, 373, 110708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yambayamba, A.M.; Handavu, F.; Kapinga, K.; Jucker, T. Tree Height Uncertainty Biases Aboveground Biomass Estimation More than Wood Density in Miombo Woodlands. Biogeosciences 2025, 2025, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeys, K.; den Bossche, A.V.; Verhelst, T.; Frenne, P.D.; Thomaes, A.; Brunet, J.; Cousins, S.A.O.; Pauw, K.D.; Diekmann, M.; Graae, B.J.; et al. Allometric-Equations-Underestimate-Woody-Volumes-of-Large-Solitary-Trees-Outside-Forests. Urban For. Urban Greening 2025, 2025, 128839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavana-Bryant, C.; Wilkes, P.; Yang, W.; Burt, A.; Vines, P.; Bennett, A.C.; Pickavance, G.C.; Cooper, D.L.M.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; et al. ForestScan: A Unique Multiscale Dataset of Tropical Forest Structure across 3 Continents Including Terrestrial, UAV and Airborne LiDAR and in-Situ Forest Census Data. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2025, 2025, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Pang, Y. Trunk Cross-Section Reconstruction and DBH Calculation from Handheld Laser Scanning Data Using Kalman Filter. J. For. Res. 2025, 37, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, K.; Selmes, N.; Anstee, A.; Tate, N.J.; Denniss, A. Estimating Tree and Stand Variables in a Corsican Pine Woodland from Terrestrial Laser Scanner Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2009, 30, 5195–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markku, Å.; Raumonen, P.; Kaasalainen, M.; Casella, E. Analysis of Geometric Primitives in Quantitative Structure Models of Tree Stems. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4581–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Nan, L.; Dong, Y.; Su, X.; Chen, F. AdQSM: A New Method for Estimating above-Ground Biomass from TLS Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Liu, J.; Benard, J.L.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, W.; Fang, X.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, S.; Dai, L. Spatial Variation and Temporal Instability in the Climate–Growth Relationship of Korean Pine in the Changbai Mountain Region of Northeast China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 300, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dai, L.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Qi, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, G.; Wei, Y.; Shao, G. Changes in Carbon Density for Three Old-Growth Forests on Changbai Mountain, Northeast China: 1981–2010. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kükenbrink, D.; Gardi, O.; Morsdorf, F.; Thürig, E.; Schellenberger, A.; Mathys, L. Above-Ground Biomass References for Urban Trees from Terrestrial Laser Scanning Data. Ann. Bot. 2021, 128, 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Bi, H.; Jin, X.; McLean, M. A New Method of Calculating Crown Projection Area and Its Comparative Accuracy with Conventional Calculations for Asymmetric Tree Crowns. J. For. Res. 2024, 35, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Strimbu, B.M. Comparison of Mature Douglas-Firs’ Crown Structures Developed with Two Quantitative Structural Models Using TLS Point Clouds for Neighboring Trees in a Natural Regime Stand. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Su, Y.; Hu, T.; Jiang, L.; Mi, X.; Lin, L.; Cao, M.; Wang, X.; Lin, F.; Wang, B.; et al. The Coordinated Impact of Forest Internal Structural Complexity and Tree Species Diversity on Forest Productivity across Forest Biomes. Fundam. Res. 2024, 4, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitel, J.U.H.; Basler, D.; Braun, S.; Buchmann, N.; D’Odorico, P.; Etzold, S.; Gessler, A.; Griffin, K.L.; Krejza, J.; Luo, Y.; et al. Towards Monitoring Stem Growth Phenology from Space with High Resolution Satellite Data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 339, 109549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Xiao, H.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, X.-G. A New Canopy Photosynthesis and Transpiration Measurement System (CAPTS) for Canopy Gas Exchange Research. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2016, 217, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, L.; Kunz, M.; Fichtner, A.; Reich, K.F.; Bienert, A.; Maas, H.-G.; von Oheimb, G. Effects of Local Neighbourhood Diversity on Crown Structure and Productivity of Individual Trees in Mature Mixed-Species Forests. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, J.; Fagan, W.F.; Worthy, S.J.; Thompson, J.; Uriarte, M.; Zimmerman, J.K.; Umaña, M.N.; Swenson, N.G. Tree Crown Overlap Improves Predictions of the Functional Neighbourhood Effects on Tree Survival and Growth. J. Ecol. 2019, 107, 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Mazón, M.; Klanderud, K.; Finegan, B.; Veintimilla, D.; Bermeo, D.; Murrieta, E.; Delgado, D.; Sheil, D. How Forest Structure Varies with Elevation in Old Growth and Secondary Forest in Costa Rica. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 469, 118191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J.B.; Gannon, B.M.; Feinstein, J.A.; Padley, E.A.; Metz, L.J. Simulating Spatial Complexity in Dry Conifer Forest Restoration: Implications for Conservation Prioritization and Scenario Evaluation. Landsc. Ecol. 2020, 35, 2301–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Dong, S.; Li, S.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, H.; Yeomans, J.; Li, Y.; Shen, H.; Wu, S.; et al. Using the Random Forest Model and Validated MODIS with the Field Spectrometer Measurement Promote the Accuracy of Estimating Aboveground Biomass and Coverage of Alpine Grasslands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 112, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Chianucci, F.; Mai, C.; Lin, W.; Leng, P.; Luo, S.; Yan, B. Comparison of Seven Inversion Models for Estimating Plant and Woody Area Indices of Leaf-on and Leaf-off Forest Canopy Using Explicit 3D Forest Scenes. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackenberg, J.; Morhart, C.; Sheppard, J.; Spiecker, H.; Disney, M. Highly Accurate Tree Models Derived from Terrestrial Laser Scan Data: A Method Description. Forests 2014, 5, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, L.; Chirici, G.; Marchetti, M. Biomass Estimation of Xerophytic Forests Using Visible Aerial Imagery: Contrasting Single-Tree and Area-Based Approaches. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Feng, Z.; Chen, P.; Ullah Khan, T.; Lian, Y. Nondestructive Estimation of the Above-Ground Biomass of Multiple Tree Species in Boreal Forests of China Using Terrestrial Laser Scanning. Forests 2019, 10, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Papa, D.; de Almeida, D.R.A.; Silva, C.A.; Figueiredo, E.O.; Stark, S.C.; Valbuena, R.; Rodriguez, L.C.E.; d’Oliveira, M.V.N. Evaluating Tropical Forest Classification and Field Sampling Stratification from Lidar to Reduce Effort and Enable Landscape Monitoring. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 457, 117634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Chen, D.; Sun, X.; Gao, H. A Comprehensive Crown Profile Model of Planted Larix Kaempferi from Different Latitudes in China. Eur. J. For. Res. 2024, 143, 1429–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Trees | DBH (sd, cm) | H (sd, m) | CPA/Overlap Rate (m2/%) | TV/Prop. (m3/%) | SV/Prop. (m3/%) | VRSB | TB/Prop. (t/%) | SB/(t/%) | BRSB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plot | 580 | 23.1 | 14.32 | 14,882.56 | 762.7 | 424.12 | 1.25 | 350.84 | 195.85 | 1.26 |

| (20.23) | (7.76) | 59.1 | /100 | /100 | /100 | /100 | ||||

| Healthy Tree | 528 | 23.56 | 14.74 | 13,975.9 | 723.1 | 402.58 | 1.26 | 332.82 | 185.96 | 1.27 |

| (20.47) | (7.72) | 54.6 | /94.9 | /94.9 | /94.9 | /95.0 | ||||

| Unhealthy Tree | 52 | 18.4 | 10.35 | 906.66 | 39.56/ | 21.54 | 1.19 | 18.02 | 9.89 | 1.22 |

| (16.93) | (6.94) | 7.2 | /5.1 | /5.0 | /5.1 | /5.0 | ||||

| HTDBH ≥ 20 cm | 215 | 43.86 | 22.81 | 10,243.62 | 696.19 | 385.47 | 1.24 | 318.88 | 177.3 | 1.25 |

| (17.68) | (3.79) | 26.7 | /91.3 | /90.9 | /90.9 | /90.5 | ||||

| HTDBH ≥ 30 cm | 156 | 51.19 | 24.23 | 8607.42 | 657.46 | 360.87 | 1.22 | 300.98 | 166.01 | 1.23 |

| (15.21) | (2.87) | 19.2 | /86.2 | /89.7 | /85.8 | /84.8 | ||||

| DT of 5 | 299 | 32.12 | 18.64 | 10,165.76 | 649.86 | 361.42 | 1.25 | 296.94 | 165.98 | 1.27 |

| (22.02) | (6.97) | 30.6 | /85.2 | /85.4 | /84.6 | /84.7 | ||||

| DT DBH ≥ 20 cm | 187 | 44.98 | 23.17 | 9115.44 | 638.34 | 352.76 | 1.24 | 294.15 | 161.84 | 1.25 |

| (17.97) | (3.39) | 23.9 | /83.7 | /83.2 | /83.8 | /82.6 | ||||

| DT DBH ≥ 30 cm | 138 | 52.2 | 24.43 | 7743.69 | 605.86 | 331.62 | 1.21 | 276.71 | 153.2 | 1.23 |

| (15.38) | (2.7) | 18.4 | /79.4 | /78.2 | /78.9 | /78.2 |

| Taxon | Number of Trees (N) | DBH (cm) | H (m) | Components | a | b | R2 | rRMSE (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min. | Max. | Mean | Min. | Max. | Mean | |||||||

| P. koraiensis | 69 | 6.5 | 92 | 44.1 ± 15.5 | 4.7 | 29.8 | 22.9 ± 5.3 | Branch | −3.14 | 2.41 | 0.81 | 10.05 |

| Stem | −3.21 | 2.51 | 0.96 | 4.11 | ||||||||

| T. amurensis | 124 | 5.2 | 107.1 | 25.2 ± 19.6 | 5.5 | 29.2 | 16.6 ± 6.5 | Branch | −5.87 | 3.13 | 0.91 | 20.74 |

| Stem | −2.36 | 2.33 | 0.97 | 7.05 | ||||||||

| Q. mongolica | 18 | 5.3 | 83.5 | 42.9 ± 27.2 | 5.1 | 30.2 | 20.0 ± 7.4 | Branch | −6.72 | 3.36 | 0.93 | 15.79 |

| Stem | −1.51 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 2.26 | ||||||||

| F. mandshurica | 33 | 6.4 | 113.8 | 41.8 ± 27.5 | 8.8 | 30.7 | 23.0 ± 4.9 | Branch | −4.66 | 2.78 | 0.95 | 8.97 |

| Stem | −1.48 | 2.2 | 0.98 | 4 | ||||||||

| A. mono | 55 | 5 | 76.1 | 21.6 ± 15.7 | 4.5 | 25.7 | 14.8 ± 6.5 | Branch | −3.13 | 2.53 | 0.93 | 15.97 |

| Stem | −2.07 | 2.33 | 0.96 | 9.61 | ||||||||

| Species | Component | TLS | Chen | He | Dong | Dai | Zhou |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. koraiensis | Stem | −0.62 | 45.70 | 10.17 | −10.66 | 8.29 | 42.67 |

| Branch | −15.72 | −92.36 | −44.60 | −86.50 | −59.24 | −93.02 | |

| T. amurensis | Stem | 2.32 | −4.66 | 3.90 | 45.92 | 3.43 | -- |

| Branch | −8.96 | −86.34 | −32.98 | −79.57 | −36.10 | -- | |

| Q. mongolica | Stem | 1.34 | 10.43 | 0.00 | −0.94 | -- | 56.27 |

| Branch | −28.38 | −80.55 | -- | −4.14 | -- | −68.90 | |

| F. mandshurica | Stem | 5.40 | -- | 34.80 | 4.15 | 34.01 | -- |

| Branch | 5.77 | -- | 120.12 | −11.71 | 114.88 | -- | |

| A. mono | Stem | 1.86 | 1.43 | −5.20 | −1.90 | -- | -- |

| Branch | −4.32 | −94.84 | −53.39 | −69.20 | -- | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, J.; Chen, Q.; Wu, Z.; Gao, T.; Zhou, L.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, D. Quantifying Broad-Leaved Korean Pine Forest Structure Using Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), Changbai Mountain, China. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244049

Luo J, Chen Q, Wu Z, Gao T, Zhou L, Deng J, Zhang Y, Yu D. Quantifying Broad-Leaved Korean Pine Forest Structure Using Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), Changbai Mountain, China. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(24):4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244049

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Jingcheng, Qingda Chen, Zhichao Wu, Tian Gao, Li Zhou, Jiaojiao Deng, Yansong Zhang, and Dapao Yu. 2025. "Quantifying Broad-Leaved Korean Pine Forest Structure Using Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), Changbai Mountain, China" Remote Sensing 17, no. 24: 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244049

APA StyleLuo, J., Chen, Q., Wu, Z., Gao, T., Zhou, L., Deng, J., Zhang, Y., & Yu, D. (2025). Quantifying Broad-Leaved Korean Pine Forest Structure Using Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), Changbai Mountain, China. Remote Sensing, 17(24), 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17244049